This book is about risk management: getting out of or avoiding stocks before they destroy portfolio performance and understanding the fundamental and technical warning signs that will help you do that. While our methods draw upon years of experience, don’t just take our word for them. The many examples included in these pages emphasize our process, using real-time analysis and decisions, rather than a retrospective look at what we might have found had we been paying attention in the first place.

Experience is crucial, but we also rely on quantitative data to support our process. In Chapter 2, we focused on how companies can manipulate the top line to mask deterioration in their businesses. Often, people use the price-to-sales ratio as a measure of valuation, because of the conventional wisdom that revenue is much less likely to be manipulated than earnings. Every reader now knows that we view this not only as a fallacy, but one that is dangerous to investment returns. However, combining simple rules of valuation with earnings quality supports the point that stocks priced for great expectations founded on potentially aggressive revenue recognition are a sucker’s bet.

Expectations1 play an important role in the performance of stock prices over time. A great company may not be a great stock to own, if the market has fully valued its future prospects but investors’ expectations remain high. I (John) first learned this lesson as a freshman in college, when I happened to pick up the book Super Stocks . If there is a title more appealing to an 18-year-old who wants to make money, I don’t know it! So I grabbed it, knowing nothing about its content or author.

First published in 1984, Super Stocks 2 was written by Kenneth Fisher, a longtime contributor to Forbes , manager of billions of dollars through his firm Fisher Investments, and the son of famed investor Philip Fisher. The book focuses on growth stocks, specifically highlighting the price-to-sales ratio as a way to accurately value companies laboring under high expectations. Fisher advocated buying growth stocks with low price-to-sales ratios and selling them when the ratio exceeded 3:1 to avoid an inevitable “glitch”—the loss of a key customer, a slowdown in demand, supply issues, or virtually any factor that could put the brakes on growth.

Later, I interned for James P. O’Shaughnessy, author of What Works on Wall Street .3 In the decade or so since Fisher’s book was published, technology had advanced enough to allow the testing of many common market variables for their effectiveness in predicting future returns. O’Shaughnessy used historical data from Standard & Poor’s to do just that. His tests confirmed Fisher’s theory, revealing that the price-to-sales ratio was one of the most effective predictors of stock performance.

I assisted in testing some variables, and we broke the results into deciles by performance, with each decile representing one-tenth of the market. The results of the price-to-sales ratio were amazing, because they displayed a perfect stair-step pattern: Each decile performed worse than the one preceding it. So, for example, the companies in the lowest decile of price-to-sales ratio produced the highest returns. The second decile was the second-best performer, and the pattern continued all the way to the most expensive stocks, which generated the worst returns. This makes sense when you consider that the stocks in the highest decile—the most expensive, carrying the weightiest expectations—are often the ones people love to own. They may have intoxicating stories and glossy press releases, but they produce the worst returns over time.

Both Fisher and O’Shaughnessy theorized that price-to-sales is a better valuation metric than price-to-earnings because sales are much harder to manipulate. But after working with Howard Schilit and David Tice and managing a couple of short-selling hedge funds, I found this to be untrue. A company can manipulate sales to mask deterioration in revenue growth in numerous ways, including changing its revenue-recognition policy, offering incentives to customers, and changing the presentation of the balance sheet. This is why we devoted so much attention to revenue recognition before we delved into the three financial statements.

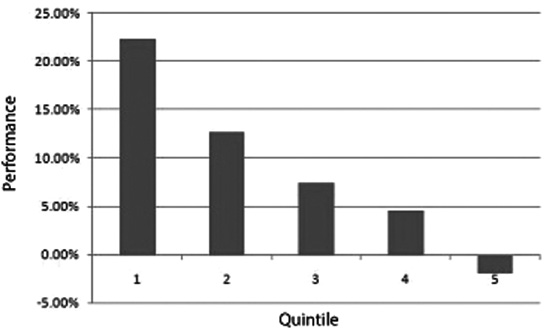

Recently, we once again tested the theory that the price-to-sales ratio can be predictive of future results. We focused on technology stocks, because they’re one area of the stock market that never fails to seduce people out of their hard-earned money. Every year and every decade touts the next big tech thing, with social networking the buzz du jour at writing. We tested the performance of all technology stocks in the S&P 1500 over the past 10, years based simply on their price-to-sales ratios. The results were astonishingly similar to both Fisher’s and O’Shaughnessy’s. Figure 9.1 illustrates the performance of technology stocks by their price-to-sales ratio quintile.

Figure 9.1 Performance of S&P 1500 technology stocks, based on price-to-sales ratio.

The quintiles in Figure 9.1 move from left to right—number 1 to 5—from lowest price-to-sales ratio to highest. In the S&P 1500 Index, the lowest quintile by price-to-sales ratio (in other words, the cheapest) returned an average of 22.33 percent over the past 10 years. The next three quintiles returned averages of 12.7, 7.4, and 2.5 percent. The most expensive 20 percent of the technology stocks returned minus 2 percent annually.

The conclusion is simple. Eras change, as do the companies that are traded in the stock market and their management teams. And technology certainly changes; a 5¼-inch disk drive was the latest thing when Fisher wrote the first edition of his book. But human nature never changes. Investors persistently overestimate the future prospects of some companies by bidding their stocks up, relative to revenues, to unsustainable levels. This leads to disappointing returns for shareholders. You can identify these companies by looking for a high price-to-sales ratio, specifically one in the highest decile. So the next time you consider buying a stock, think hard about the expectations already embedded into the stock price. Those expectations can continue to grow for a long time, but they almost always end badly.

Tom notes that consideration of expectations is exactly the mindset of the long-side value investor. When a stock reflects no or low expectations, it has a huge margin of safety. So long as the fundamentals are at least decent—not even good or great—you aren’t paying for inflated expectations. Those who pay for high expectations don’t understand that they are accepting too little potential reward for the risk that the stock will fail to meet the expectations—and crash. Those who pay for low expectations take on less risk and pay very little for their upside—they have low cost or even free optionality.

Adding a second variable, however, can shed light on what happens when the stock is priced for perfection and management stretches to make their quarterly results. The greater the performance expectations embedded in a stock’s valuation, the more pressure on management to meet or exceed those expectations. Because no one can know exactly what that pressure consists of—no eavesdropping behind closed doors or reading the CEO’s psychiatrist’s notes—no one can finish this book without understanding how strongly we rely on days sales outstanding (DSO).

It’s so important that it begins the financial analysis in Chapter 2 and takes us out in Chapter 9 with a loud DSO bang, leading to how we use DSO and other indicators in a new and easy way for you to take advantage of the learning in this book. The DSO indicate how long it takes for a company to collect on its accounts receivable. This is important, because the longer it takes a company to collect its dollars, the greater the risks to its business model. Anything can happen until you have that dollar in your hand: Customers may go bust and fail to pay, or cash flow can suffer because revenue has been booked but the money hasn’t come in the company’s coffers.

In all our financial statement discussions, you learned that our primary concern about any metric is with change over time. So too with DSO, which we also examine over time. Upward-trending DSO can point to the greatest risk of all: aggressive revenue recognition. When companies are under pressure to meet quarterly targets, they often offer incentives—extended payment terms, reduced prices, or both—in order to induce customers to sign a contract today that they may well have signed anyway later, borrowing revenue from the future.

A fertile ground where management feels this pressure is in “growth.” Any effort to study market history shows centuries of stock touters seducing investors with high-growth potential. Investors believe that advances in technology promise unlimited possibilities, so of course the companies offering these life-changers must bring stock gains. Right?

Wrong. Investors’ expectations are too high in these cases. They expect that subverting old markets and opening new ones will create riches beyond their dreams. The herd instinct compounds overestimating success and brings ever-higher multiples relative to their revenue. CEOs, insiders, and venture capitalists make out like bandits, leaving shareholders holding the bag.

The desire to make out like bandits and disregard for shareholders lead management to do anything to keep the blush on the rose. DSO chicanery is rife, especially among tech companies. Customers know that technology companies book most of their revenue toward the end of the quarter, so they commonly use this to their advantage, waiting to make a purchase and then haggling for better terms. This creates a vicious circle, as more and more customers wait it out, putting greater and greater pressure on the company to make its quarterly revenue estimates.

Combining the price-to-sales ratio and the change in DSO provides better and more stable returns than using the price-to-sales ratio by itself. So, we’re going to rate stocks using both metrics and combine those quintiles into new ones.

Figure 9.2 shows that, in the S&P 1500, the lowest combined quintile—the cheapest stocks by price-to-sales ratio, with the highest-quality credit terms—returned 22.6 percent annually over the past 10 years. The next three quintiles returned 13.2, 6.8, and –1.2 percent, respectively. The most expensive stocks, with the loosest credit terms returned –2.7 percent annually.

Figure 9.2 S&P 1500 performance, based on combined quintiles (price-to-sales ratio and credit quality).

Our study turned up a few interesting tidbits. While the lower quintiles in this study resemble those in the simple price-to-sales study above, Figure 9.2 turns negative in the fourth quintile, not the fifth. Also, incorporating DSO into the model is more statistically significant than using price-to-sales alone. The data back up our theory that companies that stretch to make financial targets will falter and suffer a pounding by the market. Because this is statistically significant, it is more likely to yield usable results in the future as well.

Performance is also fairly consistent over time. The only years where the highest earnings-quality stocks underperformed the poorest earnings-quality stocks was 2008—and only by a fraction—and in 2011, by about 5 percent. Interestingly, in the junk rally off the market lows in 2009, the highest-quality stocks outperformed by almost 10 percent. Furthermore, in the liquidity-fueled phase of quantitative easing in 2010, the highest-quality stocks outperformed by approximately 25 percent. One might have expected that easy money would have pushed investors to take excessive risks, boosting the lowest-quality stocks. But no.

If management teams can spackle over a dent in their businesses by offering customers looser credit terms and inflating short-term revenue, they will do so, even as the walls crumble around them. When expectations for companies like that are already high to begin with, take cover.

We provide this analysis to show that earnings quality should be a component of every investor’s toolkit. A better understanding of the quality of a company’s reported financials will improve your success rate as you zero-in on companies where that catalyst is going to be a significant and sustainable increase in earnings power.

Not all investors have the time or inclination to put the work into picking individual stocks. Instead they invest passively in broad market or sector indexes. There are two problems with this: Indexes include bad stocks as well as good stocks, and most index funds are market-capitalization weighted, tilting toward stocks that have already been through rapid growth phases with some of their best returns behind them.

Investors may then attempt to overcome the problem that indexes include losers. They then know that individual stocks are best, but don’t have the time, so they hire active investment managers of mutual funds. But statistics show that most managers fail to outperform indexes over time.4 This is in part because only a small percentage of stocks are the huge winners in a market cycle. Only 25 percent of stocks accounted for all of the gains in the Russell 3000 from 1983 to 2007. So, if you’re not invested in a disproportionate percentage of those big winners (while also getting hammered in the nearly two-thirds of stocks that are underperforming), then you’re going to fail to keep pace with—let alone outperform—the market, especially after accounting for fees and expenses.

Some indexes attempt to overcome the market cap weighting issue by assigning weights based on fundamental factors, such as revenue or dividends. But while a stock may have a market cap greater than another stock because of prior success, that says nothing about the future. Most companies make it into the indexes after their heady growth phase is in the rearview mirror. The larger they grow, the harder it is to keep growing at anywhere near the same percentage rates. Other indexes are equal-weighted, to avoid the larger capitalization bias in the index construction altogether, but there is still a threshold to cross in order to be admitted.

Weighting companies based on dividends, for example, attempts to take advantage of the fact that investors may prefer higher yields relative to lower ones, all else being equal. As a result, those higher-yielding stocks may return more in the future. Even so, these indexes still include all of the bad stocks (those that maintain or increase dividends unsustainably, through debt, or where cash flow is declining) as well as the good stocks (whose stable and increasing dividends come from fundamental performance). So, we are back at square one.

Therefore, for internal use, we have created our own index, modestly called the Del Vecchio Earnings Quality Index (sound of Tom applauding).5 We weight stocks based on their earnings quality, rather than revenue, dividends, or other fundamental factors. Our model differentiates good stocks from bad stocks. We have emphasized that a great company may be an awful stock, especially if the earnings power is being driven by unsustainable sources. The factors I developed are based upon my years of experience in analyzing stocks to short in all market environments. Some are unique calculations that combine fundamental factors in ways previously not considered.

Figure 9.3 illustrates the performance of stocks of the S&P 500 based on their earnings quality, as opposed to market capitalization, dividends, revenue, or other fundamental factors. From this an index can be created that avoids the problems inherent in market capitalization weighting.

Figure 9.3 S&P 500 performance based on earnings quality.

What if we then modify the index to exclude the stocks the Del Vecchio model deemed “bad?” Again, most stocks underperform the indexes over time. And only a small fraction of securities account for all of the indexes’ gains. Therefore, if we exclude too many stocks, we run the risk of leaving out many big winners. However, we know we are going to have a fair share of underperformers as well. So we only exclude those stocks that have the highest propensity for a negative earnings-driven event, such as an earnings miss or SEC investigation. Table 9.1 shows the results.

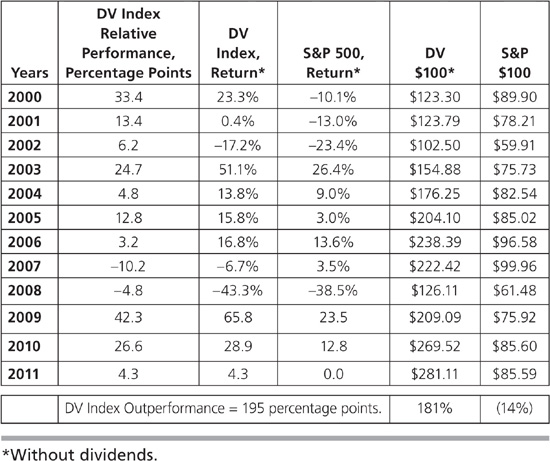

Table 9.1 Del Vecchio Earnings Quality Index versus the S&P 500: 2000–2011

The DV Index substantially outperforms. Through the lost decade to December 31, 2011, this strategy produced 181 percent absolute return versus the S&P 500’s 14 percent loss, and a relative return of 195 percentage points more.

Note, too, that having a subset of the index hold low-quality—but not the lowest quality—stocks is actually beneficial. Why? Because the highest-quality stocks may ultimately outperform over the long run, but there can be significant periods of time where low-quality stocks rule the roost, such as during the massive run-up after the market bottomed in 2009.

This new way of thinking about indexing shows what is possible and is particularly useful to institutional investors. An entire consulting industry makes its money advising pension funds, endowments, non-profits, family offices, and more on choosing vehicles for asset allocation. In an era where the Modern Portfolio and Efficient Market theories are dead,6 they still rule large swaths of the institutional roost. Even this industry’s consultants recommend to their clients active managers, almost without exception with gazillion-year track records. It’s likely that they have far too many assets under management to do anything but buy large caps that, in the end, mimic the averages because, in fact, they are the averages.

Most RIAs simply index and asset allocate their clients through mutual funds and ETFs to avoid legal and client troubles for doing anything other than what everyone else is doing. That’s why mutual fund managers are incentivized for outperforming usually by only one or two percentage points: if they do too well, RIAs sell their funds when it’s time to rebalance the asset allocation. What a racket—you win, you lose!

Institutions and RIAs believe that asset allocation, however performed, and including all sorts of alleged new “classes,” such as private equity, reduces drawdowns enough so that clients can distribute whatever they need to pensioners, insureds, university and hospital operating funds, and profligate offspring’s trust fund distributions. Why would they need to short? Asset allocation is their baby blanket.

If asset allocation—passive or active—worked, it would have worked in 2008, but it didn’t.7 A long-short strategy would have done well. Putting together our (John’s and Tom’s) performance over the years shows a long-short strategy that performs consistently. Employ Chapter 6’s research and experience-backed value-with-catalysts approach on the long side, the many chapters on the short side, and this book’s earnings quality keys on both. It works.

Look, we know you can’t change human nature or business. Business is in business to give people what they want. There is nothing to be gained by trying to change the financial decision makers’ minds about what scares them or makes them greedy. But it’s precisely because human nature is not going to change that those who use the techniques in this book will find it surprisingly easier over time and with practice to outperform in ways they didn’t imagine.

Current indexing, asset allocation, blah blah blah—they are all just giving the people what they want: mediocrity. Financial industry products, discredited academic theories, and the fact that most people prefer things that are easy and simple may do no harm, but they also provide only mediocre returns. But by thinking in a new way about indexing, investors can start to avoid the blowups and pull in some nice returns.

Most investors spend all their time figuring out long investing for growth, but they never realize that limiting losses is what really matters. What you will not find in books or blogs are more than a handful of resources on avoiding or profiting from the nuclear portfolio bomb, and none as practical as what we’ve discussed in these pages.

We know: everyone has something to offer. But what we have done, we hope, is present only the tools that matter. We prioritize. You should know now, for example, that if you do nothing else, “DSO trend” should be your last words at night and first in the morning. So this book is designed to be a nuts-and-bolts, practical start, something you can start using Monday morning in a practical long-short portfolio managed according to our principles.

You can also visit our Web site www.deljacobs.com to keep informed of new ways to use the information in this book. For those and everything else, start as soon as you can, and practice, practice, practice—but not just to get to Carnegie Hall. Become the person who can afford the box seats.