by Daniel I. Block

Introduction

The book of Ruth opens with “in the days when the judges judged,” suggesting that ancient Israelites regarded the events described in the book of Judges as occurring in an identifiable historical period. In one sense, the purpose of Judges is to explain how the Israelites made the transition from being a nomadic people wandering in the desert to the settled agriculturalists that provided the basis for the monarchies of Saul and David. One might have expected their conquest of Canaan, as described in Joshua, to have been followed quickly by the development of sophisticated monarchic political institutions, but this process took from three to four hundred years (depending on the date of the Exodus).1

Much of what is described in Judges and the literary forms incorporated in the book find counterparts in extrabiblical writings from the second and first millennia B.C. The book contains annalistic summaries of conquests, a victory hymn, prayers, prophecies, political speeches, a fable, geographic equations (Bethel = Luz), and so on, all of which are attested outside the Bible. However, while the literary style represented by Judges resembles other biblical compositions (Joshua, Samuel–Kings), it is unlike anything found outside the Bible in the ancient Near East. Whereas the archaeologists’ spades have unearthed inscriptions with literary links to virtually every type of writing found in Judges, nowhere do we find a coherent portrayal of history incorporating the forms and contents of these documents as we find in Judges.

The nearest analogues are the historigraphic writings of Herodotus and Thucydides, but these are far removed from the composition of Judges—in time (fifth century B.C.), space (Greece), and language (Greek). Whereas other ancient Near Eastern societies managed to preserve literary artifacts that contain snippets of historical and cultural information, these remain isolated and unintegrated; they provide the raw materials necessary for historical composition, but none represents the kind of intentional historiography as found in Judges. The biblical author has taken the raw materials and crafted a document that is not only compelling, but also represents a remarkable literary achievement. By deliberately selecting, arranging, and shaping these materials, he presents a picture of the Canaanization of Israelite culture between the Conquest and the establishment of the monarchy.

Historical Background

For the most part, the events described in Judges take place in Canaan, the small strip of land on the eastern Mediterranean sandwiched between Egypt to the south and the territories occupied by Phoenicians and Arameans in the north. Most of its narratives involved Israelites living west of the Jordan, though occasionally the effects spilled over into the Transjordan (e.g., Gideon’s pursuit of the Midianites, ch. 8). The account of Jephthah (10:6–12:7), located in the region of Gilead east of the Jordan, represents a significant exception.

According to chronologies established by archaeologists, the events described in this book transpired in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron (Iron A and B) Ages. These labels are based on cultural features, specifically the technological transition from bronze to iron as the primary metal of choice. The significance of this shift, and the cultural lag experienced by the Israelites vis-à-vis the Canaanites, is reflected in 1:19 and 4:3, 13, where the narrator acknowledges the latter’s military superiority because they possessed iron chariots.

Establishing the chronological sequence of the events described in Judges poses special problems. While many of the places named in the book can be firmly identified geographically, not a single character is named in any contemporary ancient Near Eastern literature. Consequently, attempts to establish chronological relationships depend on internal biblical evidence of the book on the one hand, and extrabiblical evidence for contemporary developments on the other. We will deal with these separately.

Internal evidence for the chronology of the period of the Judges. Temporal notices appear regularly in this book, declaring the duration of the oppressions and the lengths of the respective rulers’ terms in office. The internal data may be summarized in tabular form.

But this scheme is difficult to reconcile with 1 Kings 6:1, which declares that Solomon commenced constructing the temple 480 years after the Exodus. Taken together, the times given in the Bible for the significant events between the Exodus and the building of the temple yield the following scheme (see Table 2).

The problem is obvious: 591 years exceeds the 480 cited in 1 Kings 6:1 by more than a century.2 The difficulty may be partially resolved by allowing for chronological overlapping among the various judges. It is evident that many of the judgeships were tribally based, and the oppressions affected only portions of the Israelite population, as the following chart suggests (see Table 3).

Table 3: Points of Pressure on Israel

|

Enemy

|

Deliverer

|

Tribal supporters

|

Locus of pressure

|

|

Moabites

|

Ehud

|

Benjamin

|

Heartland

|

|

Philistines

|

Shamgar

|

|

Southwest

|

|

Canaanites

|

Barak

|

Ephraim, Zebulun, Naphtali, Issachar

|

North

|

|

Midianites

|

Gideon

|

Manasseh, Ephraim

|

Heartland

|

|

Ammonites

|

Jephthah

|

Gileadites

|

Transjordan

|

|

Philistines

|

Samson

|

Dan

|

Southwest

|

It appears from 5:6 that the judgeships of Barak and Shamgar overlapped, and from 10:6 that the Ammonite and Philistine oppressions overlapped, which suggests concurrency between several of the judges’ terms in office, cutting at least eighteen years from the total. Since Samson, Eli, and Samuel all had to deal with the Philistines, their tenures in office may also have run concurrently during the forty years of Philistine oppression cited in 1 Samuel 4:18, allowing a deduction of thirty-two additional years from the total in Table 1. Abimelech’s three years should perhaps be deleted from the computation, since he was not an actual judge.

The biblical evidence for the duration of Samuel’s and Saul’s terms in office is uncertain. The reference to forty years for the latter in Acts 13:21 may include Samuel’s tenure. Even so, the number forty for Saul seems high and may be intended as a round figure for one generation.3 If Samuel’s tenure is included in the forty years of Philistine oppression, as suggested above, and Saul functioned as king for twenty, which seems reasonable,4 then the figures total 486 years—very close to the 480 years cited in 1 Kings 6:1.

The use of the number 480 raises the question whether this entire scheme is perhaps artificially constructed. The figure, representing twelve generations of forty years, seems to reflect a theology of history more than a precise chronology of historical events. The inconsistencies with which the author uses numbers may suggest that we should not try to force the calculations into a coherent scheme. Figures included in the formula “PN judged Israel x years,”5 and those identifying lengths of oppressions6 tend to be precise, whereas periods of peace are announced as multiples of forty, presumably because this was considered a generational lifespan.

This impression of literary structuring is strengthened by the fact that the number of judges/rulers in/over Israel is exactly twelve, matching the number of tribes.7 The differences in the types of numbers used in the book probably derive from the sources used by the author, who made no effort to synchronize them with external chronological data or make them conform to any predetermined quota.

This conclusion is reinforced by Jephthah’s claim in 11:26 that the Israelites have occupied Heshbon for three hundred years. If the Ammonite and Philistine oppressions coincided, this speech must have been delivered within forty to fifty years of David’s tenure (ca. 1050 B.C.), which fixes the date of Conquest at 1350 and the Exodus at 1390 B.C. But this does not square with 1 Kings 6:1 either, according to which, if taken literally, the Exodus occurred in 1446 B.C. However, the reader should note that, unlike the 480 years in 1 Kings 6:1, this figure is not given by the narrator, but by a character in direct speech.

Furthermore, since it is a round figure, uttered in a political speech, it may have been fabricated for polemical reasons.8 The fact that Jephthah erroneously refers to Chemosh as the god of the Ammonites (11:24)9 shows that he was not above misrepresenting historical reality in other details. One might also find support for this skeptical interpretation of Jephthah’s number from the character of the man himself. Appearing second last in the narrator’s parade of deliverers, only Samson is given a more negative character evaluation than Jephthah.

External evidence for the period of the Judges. Efforts to gain a contextual ancient Near Eastern perspective on events described in Judges are aided greatly by extrabiblical textual and material evidence. Here I will summarize their significance for understanding the period of the judges. With respect to literary evidence, the Merneptah Stela, erected in ca. 1209/08 B.C. to commemorate the Egyptian Pharaoh’s Libyan victories, concludes with a stanza celebrating his conquests in Canaan.10 This document provides the earliest extrabiblical attestation of an entity known as “Israel,” confirming that by the end of the thirteenth century B.C., the nation was a significant force in Canaan.

The so-called Amarna letters, discovered at Tel el-Amarna in Egypt in 1888–89, provide the clearest window into the Canaanite political situation at the beginning of the period of the Judges.11 This cache of more than three hundred clay tablets inscribed in Akkadian, the language of trade and diplomacy in the fourteenth century B.C., contains the written correspondence between the Egyptian king Amenhotep IV (also called Akhenaten, ca. 1352–1336 B.C.) and his vassal kingdoms in Canaan and Syria. These letters describe a political landscape dominated by a small city-states often at odds with each other and harassed by a troublesome group of landless people known as ʿapiru. In the past, this designation has been associated with biblical ʿibrîm (“Hebrews”), but this equation is no longer widely held (see comment on 11:3).12

The religious situation in Canaan during this period has been illuminated by the discovery of several collections of clay tablets from twelfth-century B.C. Ugarit on the Mediterranean coast in northern Syria. Discovered in palace and temple libraries, these texts were written in alphabetic and syllabic Akkadian cuneiform and have yielded a host of invaluable ritual and mythological texts, clarifying the relationships among the Canaanite deities mentioned in Judges and the nature of Canaanite religion found so repugnant by the author of Judges.13 Ugarit was destroyed at the beginning of the twelfth century B.C., presumably by the Sea Peoples, with whom the Philistines are associated.

Speaking of the Sea Peoples, this expression occurs only once in extrabiblical texts, in the Great Karnak Inscription of Merneptah, dated to the late thirteenth century B.C., where the Egyptian boasts of having defeated an invasion of allied forces referred to as “the foreign countries [or ‘peoples’] of the sea.”14 This was a general designation for a group that included Peleset (“Philistines,” from which Palestine gets its name), Tjeker (Sikils), Shekelesh, Denyen, Weshesh, and Shardana.15 Our knowledge of Philistine culture has been greatly enhanced by archaeological excavations at Ashdod, Ekron, Ashkelon, and Tell Qasile.16 As we will see, archaeological excavations have illuminated many critical elements in the narratives of Judges, including the accounts of the demise of Abimelech in Judges 9, especially the fortifications of Shechem, the conquest of the northern city of Dan (Laish) in Judges 18, and many others.

Although somewhat removed from Judges both with respect to time and space, the royal correspondence that archaeologists have recovered from eighteenth-century B.C. Mari offers another helpful window into ancient societies making the transition from seminomadic to settled forms of existence. These letters depict a world in which settled urban communities are coming to terms with seminomads and in which political and military institutions bear striking resemblances to those portrayed in Judges.17

Asked the LORD (1:1). In Old Testament times military leaders generally consulted their gods before embarking on military campaigns. To determine the will of the gods they resorted to a variety of oracular means, such as examining the liver of a slaughtered sheep for special markings or observing astrological phenomena. Sometimes the reception of an oracle was preceded by sacrificial rituals, as in the following report of an oracle favoring Zimri-Lim from the eighteenth-century B.C. site of Mari:

Speak to my lord: “Thus Mukannišum, your servant, ‘I have made the offerings for Dagan for the sake of the life of my lord. A prophet of Dagan of Tutt[ul] arose and spoke as follows: “Babylon, what are you constantly doing? I will gather you into a net and. . . . The dwellings of the seven accomplices and all their wealth I give into the hand of Zimri-L[im].” ’ ”18

The present text is silent on the method used by the Israelites to determine the will of Yahweh. The fact that later the Israelites went to Bethel, where the ark of the covenant was located and where Phinehas, son of Eleazar, the son of Aaron, served as high priest (20:27–28), suggests the divine will was ascertained by manipulating the Urim and Thummim, as prescribed for Joshua in Numbers 27:21 (cf. 1 Sam. 28:6).

Who will be the first to go up? (1:1). The verb “go up” reflects the mountainous terrain of much of Palestine and the common Canaanite practice of fortifying settlements on hilltops or mounds. Since campaigns of conquest often involved sieges of fortified towns rather than pitched battles between two armies in the open field, this verb became idiomatic for “to attack.”

Canaanites (1:1). Like the terms for other ethnic groups in this chapter (Perizzites, v. 5; Jebusites, v. 21; Hittites, v. 26; Amorites, vv. 34–36), “the Canaanites” is a collective gentilic expression. The cumulative evidence of second millennium B.C. references in extrabiblical texts from Alalakh, Ugarit, Mitanni, Babylon, and Egypt suggests that, although no specific boundaries are given, the peoples who lived in this region had a clear geographic and social understanding of the term “Canaan,” and that the boundaries of this region accord with Late Bronze Age realities.19 The word probably derives from the root kānā ʿ (“to bend, to bow low”). Specifically the name seems to have identified the coastal and river valley lowlands, in contrast to the hill country. But it was generalized to encompass most of Palestine west of the Jordan, modern Lebanon, and parts of southwestern Syria.20

I have given the land into their hands (1:2). As reflected in the oracle from Dagan (see 1:1), this committal formula reflects the ancient belief that the outcome of battles was always determined by the gods. This statement portrays Yahweh as a divine warrior who marches before his people, defeats the enemy, and hands their territory over to those on whose behalf he was fighting. Note also a seventh-century B.C. oracle in support of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria: “Bel (Marduk) has said, ‘Like Marduk-šapik-zeri, may Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, And I will deliver all the countries into his hands!”21

Judah said to the Simeonites their brothers (1:3). In ancient tribal contexts, tribes were often named after their “eponymous” ancestor. Although originally Judah and Simeon were full brothers, the sons of Jacob and his first wife Leah (Gen. 29:33, 35), political and military allies were frequently referred to as brothers. According to Joshua 19:1–9, the territorial allotment of Simeon consisted of scattered towns within the grant of Judah. Within a century or two Simeon ceased to exist as a separate tribe.22

Perizzites (1:4). The Perizzites were a minor branch of the pre-Israelite population of Canaan residing in the territory allotted to Judah. They are frequently identified as targets of Israel’s holy war, hence under the ḥerem law (Gen. 15:20; Deut. 7:1; Josh. 3:10; 9:1). The etymology of “Perizzite” is uncertain, but the personal name Perizzi occurs in a fourteenth-century Amarna letter written from the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni.23

Bezek (1:4). The location of Bezek is unknown, but it cannot have been far from Jerusalem. Boling suggests an identification with Khirbet Bizqa, near Gezer.24

Ten thousand men (1:4). This is obviously a rounded figure, perhaps a conventional generic number for “innumerable.” Although this figure correlates well with the figures given for the registration of Israel’s men of military age in Numbers 2 and 26 and with the song composed to celebrate David’s victory over Goliath (1 Sam. 18:7), in the light of archaeological evidence for population levels in Canaan at this time it seems inordinately high.

Based on a comparison of these numbers with those found in Assyrian records, some conclude that the numbers should not be interpreted literally but as intentionally and conventionally hyperbolic.25 A more likely option is to reinterpret the expression ʾelep, usually rendered “thousand.” Since the consonantal form of this word ( ʾlp) can also mean “clan, head of a clan,” the word may either refer to the leader of a contingent of troops a clan could muster26 or function as a collective for the troop itself.27

Adoni-Bezek (1:5). The NIV follows an ancient tradition in interpreting ʾ adōnî bezeq as a personal name, Adoni-Bezek (like Adoni-Zedek, king of Jerusalem, in Josh. 10:1–3), but this is improbable, since, unlike ṣedeq, bezeq never appears in the Old Testament or elsewhere as a name of a divinity. This expression is probably intended as a title, “Lord of Bezek,” a reference to the governor or mayor of the city.28

They . . . cut off his thumbs and his big toes (1:6). As we will learn from the Philistines’ gouging out Samson’s eyes in 16:21, the mutilation of captives was common in the ancient world. See sidebar on “Inhumane Treatment of Captives.”

Seventy kings (1:7). The number “seventy” is probably intended as a round and/or hyperbolic number, meaning “all the chieftains in the area.” In Canaanite mythology the high god El and his wife Asherah are portrayed as the parents of the seventy gods, including Baal (the male fertility deity, El’s opposite), Mot (the god of death and the netherworld), and Yam (the god of the sea). The reference to seventy offspring suggests all the gods derive from these two.29

“God has paid me back for what I did to them” (1:7). As any ancient person would have done, the governor of Bezek interprets his fate theologically: Adoni-Bezek’s reference to God is ambiguous. In ascribing responsibility for his punishment to deity he uses the generic designation ʾ elōhîm, which could refer either to Yahweh by the generic title or his own pagan god. As a Canaanite we would not expect him to refer to Yahweh, the God of Israel.

The Judahite treatment of Adoni-Bezek is likely an application of the law of lex talionis, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,” but it is striking that the newly arrived Israelites have actually adopted a Canaanite ethic. Instead of looking to Yahweh for ethical guidance (cf. Samson in 15:12–13), the Judahites find their models on treatment of captives in their predecessors in this land.

Jerusalem (1:7). The name “Jerusalem” means something like “establishment of [the god] Shalem.” Although archaeological evidence suggests the site was occupied during Early Bronze Age I, the earliest extrabiblical attestation of the name derives from the nineteenth to eighteenth century B.C. Execration texts from Egypt, where it is spelled Rusalimum. According to the Amarna correspondence, in the fourteenth century the city (spelled Urusalim) was ruled by Abdi-Hiba, a vassal of the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenophis IV (Akhenaten). The common biblical name for this place, Jebus (cf. v. 21), is unattested outside the Old Testament.30 See also comment on 18:10.

The association of Judah with Jerusalem at this early date is problematic. (1) Second Samuel 5:6–9 reports that David wrested Jerusalem out of Jebusite hands. (2) Judges 1:21 and Joshua 15:8 testify that Jerusalem was occupied by Jebusites (not Canaanites or Perizzites). (3) According to Joshua 18:16, 28, the city was located within the territory allotted to Benjamin.

The most likely explanation recognizes Jerusalem as a border city, located on the boundary between Judah and Benjamin. The city burned in verse 8 probably refers to the Jebusite fortress on the southern hill of the city, between the Kidron and Hinnom Valleys, which David eventually captured and made his capital. Accordingly, the unsuccessful Benjamite effort in verse 21 seems directed against a citadel on the north end of the city. The fact that David had to reconquer Jerusalem suggests that the Judahite hold on the city was weak and short-lived. Shortly after the Judahites sacked it, the Jebusites probably moved in from the north and took control, which they then held for several centuries.

Hill country, the Negev and the western foothills (1:9). The Canaanites targeted by this campaign are identified generally according to three topographic areas: “the hill country” (the Judaean uplands south of Jerusalem), “the Negev” (the southern part of Judah, largely desert), and the “western foothills” (the transitional region of Judah between “the hill country” and the coastal plain).31

Debir (formerly called Kiriath Sepher) (1:11). Like Hebron (v. 10), Debir is also identified by its ancient name, Kiriath Sepher. The latter name translates literally “city of the letter/document,” which suggests this site may have originally housed an official library or archive.32 However, one major Old Greek text tradition (LXXB) reads Kariassōpar, which seems to point to an original Kiriat Sopher, “city of the [muster-]officer,”33 in which case Debir may have been an important army or government post. The location of ancient Debir is still uncertain, but it most likely links with Khirbet Rabud, southwest of Hebron.34

Caleb (1:12). The name means “dog.” Although ancient Israelites considered dogs to be unclean scavengers, their value in Mesopotamia and Egypt is reflected in personal names with the form “dog of DN” (DN being the name of a deity).35 Not only his name, but also his identification elsewhere by patronymic and gentilic as “Caleb son of Jephunneh, the Kenizzite” (Num. 32:12; Josh. 14:6, 14) suggests he was not a native Israelite. “Kenizzite” suggests a link with Kenaz, an Edomite clan chief in Genesis 36:11, 15, 42.

I will give my daughter Achsah in marriage (1:12). Some modern readers find Caleb’s treatment of his daughter offensive, as if she is mere property, an object to be awarded by one man to another for a job well done. However, in this world, where clan loyalties are high and the well-being of the extended family takes precendence over personal and individual interests, Achsah probably felt honored to be given in marriage to a military hero like Othniel. As in the patricentric and patrilocal world around Israel, where fathers regularly gave their daughters in marriage to their husbands, Caleb’s actions would be viewed as perfectly normal, securing his own daughter’s well-being and honoring a worthy suitor.36

Do me a special favor (1:15). Two issues may be at stake: the paternal blessing on a daughter as she is given away in marriage (considered to be a key to her own and probably her husband’s future; cf. Gen. 24:60), or the dowry, a portion of the patrimonial estate given to a daughter at the time of marriage to ensure her a measure of security. In the ancient world the dowry could be in the form of slaves (Gen. 24:59, 61; 29:24, 29), movable property, and in exceptional endogamous cases (as here), land.37

Descendants of Moses’ father-in-law, the Kenite (1:16). Judging from the name qênî (“smith”), the Kenites may have represented an itinerant band of coppersmiths. The area south of the Dead Sea and north of the Gulf of Aqaba around Timna was an important source of copper in ancient times.38 Since Moses’ father-in-law is referred to elsewhere as a Midianite priest (Ex. 3:1; 18:1), Moses may have had more than one wife, or the Israelites were imprecise in their identification of the nomadic groups that migrated back and forth in the desert regions south of Judah, or the gentilic Kenite refers to a Midianite clan or subgroup.39

Negev near Arad (1:16). This expression (lit., “Negev of Arad”) compares with “Negev of the Kenites” in 1 Samuel 27:10. The traditional site, Tel Arad, is located eighteen miles northeast of Beersheba, on a hill rising forty meters above the surrounding landscape. Since the archaeological record of Late Bronze Age (the time of the Judges) gives no evidence of occupation of the site identified today as Tel Arad, the site referred to by this name seems to have shifted.40

City of Palms (1:16). Unlike 3:13, where the same expression refers to Jericho,41 here it functions as a generic designation for a fortified oasis settlement, most likely Tamar on the western edge of the Arabah south of the Dead Sea.42

Zephath . . . Hormah (1:17). The location of this site is unknown. The treatment of the city appears on the surface to be according to the law of ḥērem as reflected not only in Deuteronomy 7:1–5, but also according to the ninth-century B.C. Mesha Inscription, in which he describes his sacking of Nebo, an Israelite town:

I went in the night, and I fought against it [Nebo] from the break of dawn until noon, and I took it, and I killed [its] population, seven thousand male citizens(?) and aliens(?), and female citizens(?) and aliens(?), and servant girls; for I had put it to the ban [ḥrm] for Ashtar Kemosh.43

The renaming of a site accords with common ancient Near Eastern practice of conquerors renaming conquered territories (cf. the Danites’ renaming of Laish as Dan in 18:29). The town of Til Barsip (modern Tell Ahmar) on the upper Euphrates, twelve miles downstream from Carchemish, provides an interesting example of this kind of renaming. The Luwian name of the site was Masuwari, but when the Arameans gained control of the region and made it the capital of their state (referred to in Neo-Assyrian texts as Bit-Adini), they renamed it Til Barsip. Later, when Shalmaneser III of Assyria (858–824 B.C.) conquered the region, he renamed the town after himself, Kār-Shalmaneser. He also changed the names of Nappigu, Alligu, and Rugultu as Līta-Aššur, Aṣbat-lā-kunu, and Qibīt-[Aššur], respectively.44 In the present case, Hormah (ḥormâ), which means “destruction,” plays on the term ḥērem, “devoted [to God] for destruction,” the technical expression for Israel’s mandate to destroy the Canaanites utterly.

Gaza, Ashkelon and Ekron (1:18). These are the names of three cities near the Mediterranean coast straight west of the Dead Sea. Gaza is identified as Tell ʿAzza, on Israel’s southern coastal plain, three miles from the Mediterranean. Strategically located on a caravan route between Egypt and Syria, Gaza was often caught in wars between Egypt and Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia. The name first appears in a fifteenth-century B.C. list of cities conquered by Thutmose III. Its significance is reflected in the epithet for the city, “That which the Ruler Captured.”45 In the El Amarna letters the town appears as Azzatu (EA 297:32).

The importance of Ashkelon as early as the nineteenth century is reflected in its appearance in Egyptian Execration texts from this period.46 The city also figures prominently in the fourteenth-century B.C. Amarna correspondence between Canaanite city rulers and their Egyptian overlord47 and is listed among a series of Canaanite cities conquered by Merneptah in the thirteenth century.48 If any historical value is to be ascribed to the tradition that Ashkelon was founded by Mopsus, a seer and hero of the Trojan War in the twelfth-century B.C., it probably relates to the establishment of Ashkelon as a Philistine city.49 Recent archaeological excavations have dramatically demonstrated the prominence of Ashkelon as a Philistine city.50

Located twenty-two miles southwest of Jerusalem, Ekron (modern Tell Miqne) is one of the largest Iron Age sites in Israel, encompassing more than forty acres. Archaeological excavations indicate that the site was occupied as early as the fifteenth century B.C.51

At the beginning of the period of the judges these three towns were occupied by Canaanites. However, in the twelfth century the Philistines, a group representing the Sea Peoples, took over all three. Eventually, together with Ashdod and Gath, they formed the Philistine Pentapolis. Since the present text seems unaware of these events, they must have transpired soon after the arrival of the Israelites and before the appearance of Shamgar (3:31) and Samson (13:1–16:31).

Iron chariots (1:19). Judah’s failure to dislodge the inhabitants of the lowland regions is a result of the Canaanites’ technological superiority with iron chariots. See sidebar on “Iron Chariots.”

Bethel (1:22). Scholars dispute the exact location of Bethel. Based on the geographical information provided by biblical texts such as Genesis 12:8 and Judges 21:19 on the one hand, and the correlation of the name “Bethel” with Beitin, the Arabic name of the modern village, on the other, most scholars identify the city with Tell Beitin, about eight miles north of Jerusalem. However, others have located Bethel at el-Bireh, a mile or so farther west for several reasons. (1) There is no archaeological evidence for Beitin being occupied in the Late Bronze Age. (2) Beitin is not on the main north-south road between Jerusalem and Nablus.52 (3) There is no evidence for Ai east of Bethel (cf. Josh. 7–8) if Bethel is Beitin. (4) The etymological link between Bethel and Beitin is suspect.53 Consensus on the issue depends on further exploration and discovery.

They sent men to spy out Bethel (1:23). The common rendering of this verse as “they spied out” (v. 23) and as “spies” (v. 24) are both doubtful. The context and especially the use of latter word (haššōm erîm), which normally means “guards, watchmen,” suggest that here the verb wayyātîrû (hiphil of twr, “to spy”) denotes the erection of an observation post,54 presumably to watch the movements of the local population in preparation for an attack.55 An eighteenth-century B.C. text from Mari on the Euphrates reflects a similar blurring of the boundaries between spies (sakbum) and guards (maṣṣartum).56

Show us how to get into the city (1:24). If Bethel were a walled town like some of the major cities of Canaan in the Middle Bronze Age and Israel’s fortified towns of the Iron Age, the request to be shown the entrance to the city sounds ridiculous, since any passerby could have observed the nature of the walls and the location of the gates. However, the archaeological record suggests that in Late Bronze I the defenses of many towns involved a perimeter of houses constructed close together.57 Presumably the spies wanted to know the best route of access into Bethel. Their appeal to a local citizen for aid is illuminated by second millennium B.C. Mesopotamian correspondence between Zimri-Lim and his officials, who report the use of local people as scouts and guides when their army entered unfamiliar territory.58

Land of the Hittites (1:26). Contrary to the ḥerem law, the house of Joseph not only spared the life of the “traitor” (from the Canaanite point of view) but also allowed him to leave, build his own city, and continue his life as a Hittite. In these texts the Hittites are presented as one of the Canaanite ethnic groups (presumably the “descendants of Heth,” Heb. of Gen. 23).

It is doubtful the territory in question is to be identified with the Hittites (Akkadian derived from ḫatti), whose capital was in Ḫattusas in Anatolia and who vied with Egypt for hegemony over Canaan in the Late Bronze Age. Rather, the Merneptah Stele of 1209 B.C. confirms that the “land of the Hittites” refers to a region of Hatti in the northern part of the territory assigned by Yahweh to the Israelites.59 Perhaps the pockets of Hittite settlement in Palestine represented remnants of the Hittites after the decline of the Hittite empire. Technically Luz/Bethel was conquered, but in reality the city was simply transferred to a new site and continued to function as a sanctioned symbol of “the Canaanites in their midst.”

Beth Shan or Taanach or Dor or Ibleam or Megiddo (1:27). The Manassite failure to fulfill the divine mandate is summarized by listing a series of unconquered cities and their respective dependent territories in a narrow strip of land extending from the Jordan in the east to the Mediterranean in the west. Beth Shean was an important city at the junction of the Jordan and Jezreel valleys. In the twelfth century the site was under Egyptian control (under Ramesses III [1184–53 B.C.]), though later it was occupied by Philistines (1 Sam. 31:10).60

Taanach was five miles southeast of Megiddo, with which it is often linked (Josh. 12:21; 17:11; Judg. 5:19; 1 Kings 4:12).61

Dor was an important coastal town just south of the Carmel ridge.62

Ibleam is probably to be identified with Khirbet Belʿameh, guarding the easternmost pass from the Ephraimite highlands into the Valley of Jezreel.63

Megiddo was a major fortress in the Valley of Jezreel. In the Late Bronze Age, when urban development declined elsewhere, Megiddo (and Hazor) retained their character as major fortified urban sites. The city was occupied by Egyptians until the middle of the twelfth century, when it was destroyed, presumably by the Sea Peoples (Philistines). Solomon recognized its strategic location, for he rebuilt the city as a major Israelite military fortress.64

The order in which these towns are named does not follow a normal east-west itinerary. Rather the narrator moves in a straight line from the eastern extremity (Beth Shean) to the center (Taanach) to the western extremity (Dor), and then from the southernmost (Ibleam) to the northernmost site (Megiddo). The effect is not only to highlight Canaanite control of the fertile Jezreel Valley, but also the geographic wedge this created between the northern tribes and Ephraim to the south.

Settlements (1:27). The villages surrounding the captured sites are referred to as (lit.) “her daughters.” This expression refers to the satellite villages and settlements within the economic and political orbit of the town named. Since most of the villages were unfortified, in time of war their inhabitants sought protection in the “mother” town. Some have estimated that in the Late Bronze Age the radius of the areas of influence of these small-scale city-states may have averaged twelve miles—the distance one could travel in a one-day round trip.65 In the Old Testament the expression usually translated “city” or “town” refers by definition to a settlement fortified with walls and defensive gate structures.

Forced labor (1:28). This expression refers to the common ancient Near Eastern practice of conquerors subjecting conquered populations into virtual slavery, though evidence for lifetime servitude is scanty. In Mesopotamia captives could be ransomed, but until the money was raised they were put to work.66 Note how the Gibeonites were treated in Joshua 9:21 and the remnant of the original population in 1 Kings 9:20–21. This practice is distinguished from the corvée service Solomon imposed on his own people (1 Kings 9:22).

Gezer (1:29). Gezer was located on the southwest corner of the Ephraimite allotment, due west of Jerusalem, on the last of the foothills where the Judean range meets the Shephelah. Located at the western end of the Valley of Aijalon, Gezer guarded an important crossroad of Palestine, where the east-west and north-south roads intersected, which was undoubtedly one of the reasons why Solomon invested so heavily in its fortification (1 Kings 9:15–17).67

The Amarna correspondence and the archaeological evidence suggest that Gezer flourished as an economic and political center in the fourteenth century B.C. Although the town seems to have declined in significance in the Late Bronze II period, by ca. 1210 B.C. it was important enough to be listed among Merneptah’s conquests in Syria-Canaan.68 Culturally Gezer has yielded one of the most significant inscriptions from ancient Israel, the so-called Gezer Calendar, dated to the tenth century. The text is significant not only for our understanding of the history of the Hebrew alphabet, but also of the agricultural cycle one century after the end of the period of the judges (see sidebar on “Gezer Calendar” at Ruth 1:22).

Acco or Sidon or Ahlab or Aczib or Helbah or Aphik or Rehob (1:31). Though named only here in the Old Testament, Acco (later known as Ptolemais)69 was one of the most important seaports in Canaan.

Sidon was a major Phoenician city that competed with Tyre to the south for economic hegemony for centuries. The inclusion of Sidon meant that most of Phoenicia was originally included in Asher’s allotment (cf. Josh. 19:24–31). But the major Phoenician cities were never brought under Israelite control.70

Ahlab appears to be textually suspect and may be a corruption of a Canaanite counterpart to Maḥalliba (a site near Sidon) in an Assyrian inscription of Sennacherib.71

Aczib was a coastal town north of Acco.72

The location of Helbah is unknown. Some have proposed an identification with in Joshua 19:29.73

The Asherite Aphek has been identified with both Tel Kurdana, five plus miles southeast of Acco, and Tel Kabri, a large site east of Nahariya.74

Rehob was a Levitical city in Asher (Josh. 21:31; 1 Chron. 6:75), usually identified with Tell el-Bi el-Gharbi.75

Beth Shemesh or Beth Anath (1:33). Beth Shemesh, located in the Sorek Valley in the northeastern Shephelah, was 12.5 miles west of Jerusalem. The name means “House of the Sun [God],” suggesting this was the site of a temple to the solar deity. In Joshua 19:41, the place goes by the name Ir Shemesh (“City of the Sun”). While archaeological excavations have not uncovered this temple, Late Bronze II remains include some significant buildings, evidence of copper smelting, and a couple of inscribed sherds indicating some literacy among the population.76

The location of Beth Anath is unknown.77 Similar to Beth Shemesh, Beth Anat means “House of Anath,” suggesting a cult center devoted to this deity. In the mythology of the Canaanites, Anath, a prominent female goddess, is often portrayed as the consort and lover of Baal.78

Amorites (1:34). The name “Amorite” is related to Akkadian Amurru (“the west”), which could designate a direction, region, or people. The heartland of the Amorites described in Mesopotamian texts was located in northern Syria, between the western Euphrates and the Khabur and Balikh rivers. From here elements of the population apparently migrated to lower Mesopotamia, eventually achieving political control in such major cities as Larsa, Babylon (Hammurabi), and Mari.

When the Amurru/Amorites migrated west and south into the region of Palestine is not clear. It seems, however, that by the seventeenth century B.C., the term “Amurru” was increasingly used to designate central and southern Syria, and by the fifteenth century “the kingdom of Amurru” denoted a realm in the mountains of northern Lebanon. In time the expression could be used of the mountainous region farther south as well.

In the biblical texts “Amorite” is sometimes limited to a specific subgroup of the pre-Israelite populations of Palestine (Deut. 7:1, etc.). Sometimes narrators use “Amorite” where “Canaanite” would be inappropriate, particularly when speaking of the Transjordanian kingdoms of Sihon and Og and the hill country of the Cisjordan. “Canaanite” cities were generally located in the valleys and coastal regions; “Amorite” cities tended to be in the highlands. Yet the present preference for “Amorite” may have an historical base, in which case verse 36 declares the southern extent of Amorite settlement.79

Mount Heres, Aijalon and Shaalbim (1:35). This grant of land assigned to the tribe of Dan consisted of a small strip of land along the Aijalon Valley extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Judean hills west of Jerusalem, sandwiched between Judah and Ephraim. Mount Heres is identified with Yalo, twelve miles west-northwest of Jerusalem, which guarded the most important trade route through the Shephelah.80 Shaalbim is probably to be identified with Selbit, three miles northwest of Aijalon.81

The geographic designation har ḥeres (lit., “Sun Mountain”) involves an archaic term for “sun.”82 The mountain may be associated with the town Beth Shemesh (“House of the Sun”; cf. v. 33). This suggestion seems to be supported by 1 Kings 4:9, which associates Shaalbim not with Har Heres but with Beth Shemesh, which is also known as Ir Shemesh, “City of the Sun” (Josh. 19:41).83

From Scorpion Pass to Sela (1:36). The “ascent of scorpions” is presumably so named because of the problem these creatures posed for travelers through this region. Southwest of the Dead Sea,84 Akkrabim represented the farthest point on the border of Judah extending through Sela (site unknown) and up into the hills.

Angel of the LORD (2:1). The person who confronts the Israelites is identified as the mal ʾak yhwh, usually rendered “angel of Yahweh/the LORD.” Because of the popular modern view of angels as feathery, winged creatures, the translation “angel” is best avoided and replaced with either “messenger” or “envoy,” for this is precisely what mal ʾak means.85 Although the moral and spiritual scolding of an entire nation by this messenger is exceptional within the ancient Near Eastern context, the notion of human beings sent out as messengers of the gods is common. In The Report of Wenamun, an Egyptian text from the period of the judges, Wenamun advises the prince of Byblos in Phoenicia to erect a stele and inscribe on it the following message:

Amun-Re, King of the Gods, sent me, Amun-of-the-Road, his envoy, together with Wenamun, his human envoy, in quest of timber for the great noble bark of Amun-Re, King of the Gods. . . .86

Gilgal (2:1). Although Joshua 4:19 locates Gilgal “on the eastern border of Jericho,” its precise location is unknown. Tell en-Nitla, two miles east of Jericho, and Khirbet el-Mefjir have been proposed.87

My covenant (2:1). In the Old Testament the word b erît (“covenant, treaty”) is used of a pact of friendship between individuals (e.g., David and Jonathan, 1 Sam. 18:3; 20:8; 23:18), or a treaty/alliance between rulers (Gen. 14:13; 21:27, 32; 1 Kings 5:12; 20:34) or nations (1 Kings 15:19; Amos 1:9). If it is a treaty between equals, it is called a parity treaty; where it involves a superior king and an inferior ruler, it is called a suzerainty treaty (e.g., Nebuchadnezzar and Zedekiah, Ezek. 17:13–19; Egypt and the nations, Ezek. 30:5; Assyria and Ephraim, Hos. 12:1).

Some argue that the word b erît and the notion of covenant entered biblical tradition late, but the root brt is attested in twelfth-century Egyptian, fourteenth- to thirteenth-century Ugaritic, and fourteenth-century Qatna texts.88 The covenant spoken of is the one ratified by Yahweh and Israel at Mount Sinai. Here and elsewhere it is referred to as Yahweh’s covenant—never Israel’s. This accords with the pattern of suzerainty treaties contracted between Hittite overlords and their vassal kings of the late second millennium B.C., as well as the neo-Assyrian vassal treaties from the first millennium B.C.89

Altars (2:2). Like Israel’s religious rites, Canaanite rituals involved altars, which came in a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on function. The excavations at Megiddo have unearthed a small horned altar about one foot square and slightly more than two feet high, undoubtedly used for offering incense, libations of wine, or grain offerings. Also unearthed was a massive circular altar from the Early Bronze Age, more than thirty feet in diameter, on which many animals could have been slaughtered at once. The fact that Gideon uses oxen to tear down the altar of Baal on his father’s property (6:25–27) suggests a large structure.

Joshua son of Nun, the servant of the LORD (2:7). The notion of human beings as servants of deities was common in the ancient Near East. Many theophoric names (names with a reference to a god) use the root ʿebed not only in Hebrew (Obadiah, “one who serves Yahweh”), but also in the Semitic world around Israel.90 Palestinian rulers and officials named in the Amarna Letters include ʿAbdi-Aširta (“servant of Ashirtu”), Abdi-Aštarti (“servant of Aštartu”), and ʿAbdi-Ḫeba (“servant of Ḫeba”).91 Phoenician names include ʿabd ʾmn (“servant of Amun”) and ʿbd ʾšmn (“servant of Eshmun”).92

Although “servant” is often understood as a menial role, the fact that court officials in the ancient world were called “a servant of the king” ( ʿebed hammelek) demonstrates that in contexts like this it actually bears honorific significance (2 Kings 25:8). This interpretation is reinforced by the discovery of dozens of seals from ancient Palestine referring to the bearer of the seal either generally as “servant of the king” or “servant of a specific king.”

Elders (2:7). The book of Judges has elders governing both tribes on the move (as here) and settled communities, villages, and towns (8:14, 16). Later the elders of Gilead contract with Jephthah to lead their forces against the Ammonites (11:5–11). It is unclear how fixed the body of elders in Israel was or how men attained this status. Nevertheless, the title clearly designated “senior leadership” with “collective authority” in judicial and administrative matters that affected the whole village or tribe. Once the Israelites had settled down, elders conducted their business in the gates of the towns, and their deliberations were open to the public (Ruth 4:1–12).93 Such ruling councils of elders are attested widely in the ancient Near East. The eighteenth-century B.C. correspondence at Mari is particularly helpful in illuminating how elders represented villages and tribes with outsiders and before kings.94

Timnath Heres . . . north of Mount Gaash (2:9). Like Beth Shemesh in 1:33 and Mount Heres in 1:34, this name may reflect the presence of a Canaanite sanctuary devoted to the sun god. The site is probably to be identified with Khirbet Tibnah, ten miles northwest of Bethel and sixteen miles southwest of Shechem.95

Gathered to their fathers (2:10). This expression functions euphemistically for “they died and were buried.” The idiom derives from the Israelite custom of burying the deceased in family/ancestral tombs (see comment on 16:31).96

Baals (2:11). When applied to a god, the name Baal (ba ʿal) functions as a title, “divine lord, master,” rather than a personal name and is used as an appellative for many gods in the ancient world, such as the Babylonian god Marduk, also known as Bel (the Akkadian form of ba ʿal). Occurring as a divine title more than seventy times in the Old Testament, ba ʿal usually refers to the storm/weather god, who in the Canaanite mythological literature goes by the name Hadad, and several other titles: ʾal ʾayn ba ʿal (“the victor Baal”), rkb ʿrpt (“Rider of the Clouds”), and b ʿl ṣpn (“Baal of Zaphan”).

Like Mount Olympus in Greek mythology, Zaphan (biblical Zaphon), meaning “north,” was the mythical mountain on which Baal resided. It is generally identified with Jebel ʿel-Aqraʿ, located twenty-five miles north of Ugarit, near the mouth of the Orontes River in northern Syria. In Canaanite mythology Baal was one of the seventy sons of El and Asherah.97

The plural form “the Baals” does not refer to a multiplicity of gods, but to numerous manifestations of the one weather god, on whose blessing the fertility of the land was thought to depend. These manifestations are reflected in the biblical place names bearing Baal, such as Baal Peor, Baal Hazor, Baal Gad, and Baal Shalisha.

Ashtoreths (2:13). The NIV’s rendering is a mistransliteration of the divine name ʿaštārôt, presumably under the influence of 1 Kings 11:5, 33 and 2 Kings 23:13, where the form appears to represent a deliberate distortion of the original name (Ashtaroth) by vocalizing the name with the vowels of bōšet (“shame”). The present form represents a plural form of ʿaštart, commonly known as Astarte, who was worshiped widely as the goddess of love and war. This deity was identified in Ebla as Ashtar and in Mesopotamia as Ishtar, from which is derived the biblical name Esther98 (see sidebar on “Baal and Astarte”).

Anger [of the LORD] against Israel (2:14–23). The notion of divine anger with the people over whom the deity served as patron/matron is common in the ancient Near East. Where records give reasons for the divine fury, the cause tends to be for a failure to satisfy the god with proper rituals. Here the cause is failure to be devoted exclusively to Yahweh.

In this regard Israel’s religion is unique. Among the peoples around Israel the gods were much more tolerant than Yahweh. Other patron deities did not mind if their devotees worshiped other gods. Indeed, it was commonly assumed that responsibilities for the welfare of the people were distributed among the deities, which meant that in addition to a weather god, the Canaanites also recognized a god of grain, a god of wine, and so on. For example, although Marduk was the supreme deity of Babylon, the city had at least nine other temples dedicated to other divinities. One could enter the city through any one of nine gates, each named after a different deity.99 Yahweh, by contrast, tolerated no rivals (Ex. 20:3–6; Deut. 5:7–10; 6:14–15).

While Yahweh’s intolerance of the worship of other deities was unique, his expression of anger would have been familiar to many outside Israel. In the ancient world divine fury was typically expressed by the deity leaving the city and allowing enemy forces to move in to wreak havoc on the place. Yahweh’s softening toward his people and restoring peace would also have been familiar, though the pattern of rescue and restoration is different here than in most ancient accounts. Esarhaddon’s account of Marduk’s return to Babylon after a lengthy absence has Marduk himself restoring the city, and when the people have returned, he appoints a new king to shepherd them. In the book of Judges Yahweh raises up judges, who, empowered by Yahweh, lead the Israelite forces in their own rescue.100

The LORD raised up judges (2:16, 18–19). Unlike the English word “judge,” which is usually associated with judicial activity, the meaning of šōp eṭîm in the book of Judges is established here: Each one functioned as a “deliverer, liberator,” who rescued the Israelites from outside oppressors. Although the verb “judge” is applied to several individuals in this book,101 none of these persons is portrayed as exercising judicial function. The expression should therefore be interpreted more broadly as “to govern, administer, exercise leadership,”102 either in internal or in external affairs.103 Note how in the Mari texts, the Akkadian šapāṭum applied to “administrative heads of districts” accountable to the king.104 Ugaritic texts employ ṯpṭ similarly, as in the following citation:

Surely he will remove the support of your throne,

Surely he will overturn the seat of your kingship;

Surely he will break the scepter of your rule [mṯpṭk].105

There may be some merit in G. W. Ahlström’s suggestion that these “judges” should be perceived like all other Canaanite princes and petty kings of the presettlement time.106

To test Israel (2:22). The Old Testament uses three words for testing: nsh (here and in 3:1, 4; 6:39), bḥn, and ṣrp (Judg. 7:4; 17:4). When used metaphorically, the notion of testing is closely linked to the metallurgical process of producing precious metals from ore. In most instances the test is performed either for quality control (a superior’s check on the loyalty of the inferior) or quality enhancement (a superior’s effort to improve the loyalty of the inferior).107 According to verse 20, the nations do not represent the actual test; rather, in accordance with Exodus 19:5, the test consists in whether or not the Israelites will listen to Yahweh’s voice.

These are the nations (3:1). The following list of nations (v. 3) does not follow the stereotypical list (e.g., Deut. 7:1). Instead, the given names function as general designations covering the entire population of the land of Canaan.

To test all those Israelites (3:1, 4). See comment on 2:22.

Five rulers of the Philistines (3:3). Remarkably, although unlike the rest of the peoples listed here the Philistines were not native to Canaan, the memory of their involvement in the region is reflected in the modern name Palestine. The Hebrew word p elištîm (represented in ancient Egyptian texts as P-r-š-t-w) identifies one of several groups of Sea Peoples108 who swept into Palestine from Anatolia and the Mediterranean in the twelfth to eleventh centuries B.C., leaving in their wake a trail of ruins. The effect on the eastern Mediterranean is reflected in an inscription by Ramesses III (1184–1153 B.C.):

The foreign countries [Sea Peoples] made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Hatti, Kode [Cilicia], Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya [Cyprus] on, being cut off [at one time]. A camp [was set up] in one place in Amor [Amurru]. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward to Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation [of Sea Peoples] was the Philistines, Tjeker [Sikils], Shekelesh, Denye(n) and Weshesh, lands united.109

Biblical tradition, which traces their origins to Crete,110 accords with the archaeological record, which suggests they came from the Aegean. But how they arrived in Palestine is the subject of some debate: Some argue they came by sea, others that they came overland via Anatolia and down through Syria.111 It seems their original goal was to settle in Egypt, but Ramesses III was able to defeat them. He settled the vanquished forces in the coastal towns of southern Canaan, but in the mid-twelfth century, the Philistines succeeded in driving out their Egyptian overlords, forming the Philistine Pentapolis, a federation of five major city-states: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, Gath, and Gaza.112

The only Philistine ruler named in the Old Testament is Achish, identified as melek (“king”) of Gath (1 Sam. 21:10).113 Faced with a numerically overwhelming native population, the ethnically distinct Philistines appear to have valued cooperation over competition.

All the Canaanites (3:3). Extrabiblical sources from the second half of the second millennium B.C. agree with the biblical terminology in their definition of the region called “Canaan.”114 The southern border was defined by an arc from the southern tip of the Dead Sea to the southeastern shore of the Mediterranean; the Mediterranean seashore represented the western border as far north as just south of the kingdom of Ugarit; the northern border ran south of Ugarit and Alalakh almost to the Euphrates; the eastern border ran south down the Beqaʿ, through the Huleh Valley, across Lake Kinnereth (Galilee), and down the Jordan Valley to the southern end of the Dead Sea.

Here, however, the gentilic “Canaanites” appears to be used in a more limited sense, as a general designation for the inhabitants of the hill country between the territories occupied by Philistines and Sidonians on the one hand and the Jordan Rift Valley on the other.

Sidonians (3:3). The Sidonians (cf. 1:31) do not figure in the stereotypical lists of Canaanite nations whom the Israelites will displace (e.g., Deut. 7:1). Here “Sidonians” stands generally for all the Phoenicians living along the Mediterranean coast north of the area occupied by the Philistines. The frequency with which the name Sidon surfaces in extrabiblical writings reflects the city’s importance in the last half of the second millennium B.C.

Three important sources derive from the fourteenth century B.C. A Hittite incantation mentions Sidon ahead of Tyre in a list of geographic names;115 in the Ugaritic Kirta Epic, on the third day of his trek the hero makes a vow “at the shrine of the Asherah of Tyre, at the shrine of the Goddess of Sidon”;116 in the Amarna correspondence Sidon is mentioned repeatedly as one of the leaders in an anti-Egyptian coalition.117 Sidon was part of a mercantile corporation employing fifty vessels to carry trade between Egypt and Phoenicia.118

Hivites . . . Mount Baal Hermon to Lebo Hamath (3:3). Some have associated the Hivites with the Hurrians (Horites) of Genesis 36:2 and 20.119 Although Joshua 9:7 and 11:19 link the Gibeonites to the Hivites, our text seems to use the expression generally for the peoples occupying the regions north of the Sea of Galilee, in the Lebanon mountains, west of a line running from Mount Baal Hermon to Lebo Hamath. This is in line with Joshua 11:3, which has the Hivites living in the shadow of Mount Hermon. Mount Baal Hermon abbreviates “Baal Gad in the Valley of Lebanon below Mount Hermon” in Joshua 11:17.

As often occurs, different people call the same place by different names. According to a geographic note in Deuteronomy 3:9, the Sidonians called Hermon Sirion, and the Amorites called it Senir, which accords with the reference to the mountain as śryn in a Ugaritic text from the period of the Judges.120 This memory is preserved in several later biblical texts as well. Song of Songs 4:8 speaks of “the top of Senir, the summit of Hermon” (cf. also 1 Chron. 5:23). Psalm 29:6 and Ezekiel 27:5–6 associate the name with Lebanon and recognize it as a source of timber. The annals of Shalmaneser III identify Senir (Akk. saniru), “facing Lebanon,” as the location of this Assyrian’s decisive defeat of Hazael of Damascus.121 These texts suggest Mount Hermon was considered part of the Anti-Lebanon Range.

Some interpret l ebô ʾ ḥ amāt as “the Pass of Hamath,”122 but it is more likely a specific place, modern Lebweh, near the spring of Nabaʿ Labweh, one of the principal sources of the Orontes River in the Beqaʿ.123 The name appears as Labʾu in the Egyptian texts and Labaʾ û in Assyrian inscriptions.124 Later Lebo Hamath constituted the northern border of Solomon’s kingdom (1 Kings 8:65), and of Jeroboam II’s northern kingdom of Israel (2 Kings 14:25).

Canaanites, Hittites, Amorites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites (3:5). For discussion of these names see comment on Joshua 3:10.

The Baals and the Asherahs (3:7). On “the Baals” see comments on 2:11. Whereas in 2:13 the female counterpart to the Baals is identified as the Ashtaroth, here the text speaks of Asherahs. Since the Asherahs are known from other biblical contexts to have been made of wood and their demolition involved chopping them down (Deut. 7:5), the KJV rendered hā ʾ ašērôt as “groves,” that is, sacred cult trees. However, in the light of the Ugaritic evidence that has surfaced, Asherah (also identified Athirat [ ʾatrt]) is now known to have been a prominent goddess in Canaanite mythology, the wife of the high god El ( ʾil) and mother of seventy gods. Her titles in the Ugaritic myths include “Lady Athirat of the Sea” and “Creatress of the Gods,”125 which reflects her role as mother of the gods (who are referred to elsewhere as “the seventy sons of Athirat”).126

The seductive power of the Canaanite Asherah cult to the Israelites is attested by several Hebrew inscriptions in the form of blessings from the eighth century B.C. that speak of “Yahweh and his Asherah”:

• Kintillet ʿAjrud pithos 1 (northeastern Sinai): “I have blessed you by Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah.”

• Khirbet el-Qom inscriptions (near Hebron): “Uriyahu the rich wrote it / Blessed be Uriyahu by Yahweh / For from his enemies by his Asherah he has saved him / by Oniyahu / and by his Asherah / his A(she)rah.”127

Even with this new information, the mention of Asherah alongside Baal in our text (presumably as his consort) is surprising, especially since 2:13 associated the Baals with the Ashtartes. Either the author confuses the two deities, or he recognizes both as consorts of Baal in this fertility religion. In either case, in worshiping these Canaanite deities the Israelites exchange the worship of the living God for the service of wood and stone. The lofty theology, austere morality, and abstract cult of Yahwism were replaced with the tangible and exciting fertility religion.

Cushan-Rishathaim king of Aram Naharaim (3:8). This title appears straightforward. Aram, rendered Syria in the LXX, is the name given to the area populated primarily by Arameans, one of the most important ethnic groups in the late second and early first millennia. Their territory extended from northeast of the Sea of Galilee to the Taurus Mountains in the north and eastward beyond the Habur tributary of the upper Euphrates River. While his capital is not identified, the addition of Naharaim (“of the two rivers”; cf. Mesopotamia, meaning “between the rivers”) fixes his home somewhere near or east of the great bend of the Euphrates.128

During the fourteenth to thirteenth centuries B.C., this region was politically subservient to the empire of the Hittites with their capital at Ḫattuša, serving as a buffer to the Assyrians to the east and the Egyptians to the south. However, during the last half of the thirteenth century, under Tukulti-Ninurta I (1245–1208 B.C.), the region east of the great bend in the Euphrates was controlled by the Assyrians. By the end of Tukulti-Ninurta’s reign Akhlamu Arameans were infiltrating the western part of the empire. Their influence is reflected in the first appearance of Aram as the name of a region in the fourteenth-century B.C. Egyptian inscription of Amenophis III.129 On Cushan-Rishathaim, see sidebar on “Who Is Cushan-Rishathaim?”

The LORD gave Cushan-Rishathaim . . . into the hands of Othniel (3:10). The attribution of Othniel’s successes over such a formidable foe as Cushan-Rishathaim to Yahweh would have been understood by all ancient Near Easterners. It was universally acknowledged that rulers governed by the will of the gods and especially that the outcomes of battles depended ultimately on the intervention of the gods. The annals of Tiglath-pileser I (1114–1076 B.C.), an Assyrian contemporary of the later deliverers, are laced with references to the involvement of Asshur, the patron divinity of Assyria. Centuries later, a neo-Assyrian successor to Tiglath-pileser, Shalmaneser III (854–24 B.C.) credited Asshur with his victory over a western alliance of kings that included Hadadezer of Damascus and Ahab the Israelite as follows:

They marched against me [to do] war and battle. With the supreme forces which Aššur, my lord, had given me (and) with the mighty weapons which the divine standard, which goes before me, had granted me, I fought with them.130

Eglon king of Moab (3:12). The name ʿeglôn, a diminutive form of ʿēgel (“bull, calf”), also recalls the term ʿāgōl (“round, rotund”).131 Moab designates the nation state that emerged on the plateau east and northeast of the Dead Sea in the late second millennium B.C. The heartland of this nation during the period of the judges was the region between the Wadi Zered, which flows into the southeastern corner of the Dead Sea, and the Arnon Gorge, which splits the Moabite plateau into two halves. However, both the biblical record and the ninth-century B.C. Mesha Inscription suggest that for much of this time the northern half, which had been assigned to the tribe of Reuben, was under Moabite control.

Genesis 19:30–38 suggests the Moabites were relatives to the Israelites, having descended from an eponymous ancestor named Moab, son of Abraham’s nephew Lot; the name probably means “from [my] father.” The archaeological evidence for Moab in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages is incomplete and inconclusive, largely because of insufficient attention by archaeologists. However, this lacuna is filled in somewhat from the Balua Stele, which shows two Moabite rulers standing before an Egyptian deity, and a thirteenth-century B.C. topographical list of Ramesses II, which refers to his warring in Moab and capturing five forts. Apparently at this time Moab was a significant political and military force in the mind of the Egyptians.132

Whether Eglon was the king of a highly developed sedentary population or the foremost ruler over a group of tribes each led by an elder or sheikh is not clear, though his present residence in Jericho shows his preference for the town over tents. Eglon’s capital has not yet been discovered, nor has any other Moabite capital from the time of the judges. One may expect that further excavations and the carbon-dating of organic material already discovered may push back the dates of some of the evidence for an early Moabite kingdom in the Transjordan, even as they are doing for Edom to the south.133

City of Palms (3:13). “The City of Palms” is Jericho (Deut. 34:3; 2 Chron. 28:15), modern Tell es-Sultan, whose occupation dates back more than seven thousand years before the event described here. Located by an oasis in the Jordan Valley ten miles north of the Dead Sea, the site was an important stopping place on trade routes along the Jordan Valley and westward to Jerusalem, Bethel, and Ophrah. Eglon probably selected Jericho as the base of his Cisjordanian rule because of its desirable location and its longstanding history as a major Canaanite city. He is oblivious to the curse Joshua had invoked on the city in Joshua 6:26.

Ammonites (3:13). According to Genesis 19:37–38, the Ammonites were cousins to the Moabites, the descendants of the eponymous ancestor Ben-ammi (also a son of Lot with his daughter), which means “son of my paternal grandfather.” As almost everywhere in the Old Testament, the national name is b enê ʿammôn (“sons of Ammon”) rather than the gentilic form “Ammonites.” This accords with extrabiblical references to this nation, which display a remarkable preference for the compound form of the name. The most remarkable is a seventh-century B.C. Ammonite inscription on a bronze bottle, which not only gives the names of a series of Ammonite kings, but remarkably refers to the kingdom by the compound form of the name, bn ʿmn.134

The accomplishment of Amminadab, king of Banē ʿAmmōn,

the son of Hiṣṣal ʾel, King of Banē ʿAmmōn,

the son of Amminadab, king of Banē ʿAmmōn:

a vineyard and the gardens and the ʾtḥr and cisterns.

May he rejoice and be glad

for many days and distant years.

The Ammonites occupied an ill-defined territory northeast of Moab, separated from the Jordan first by the Amorite kingdoms of Sihon of Heshbon and Og of Bashan, and then their Israelite successors (Deut. 2:24–3:22). According to 2:20–21 the Ammonites had displaced an ancient people known to the Israelites as Rephaim but to the Ammonites as Zamzummim.

Amalekites (3:13). In the absence of any firm archaeological evidence for the Amalekites,135 the Old Testament remains our only source of information. Genesis 36:16 suggests the Amalekites were linked ethnically with the Edomites, though they seem to have remained a migratory people throughout their history.

Ehud, a left-handed man, the son of Gera the Benjamite (3:15). Israel’s second deliverer is identified by name and patronymic. Ehud consists of two elements, ʾ ê and hûd, which together denote “Where is the splendor, majesty?”136 Although in a troop of right-handed men a left-handed person would have been difficult to accommodate, if all the men were left-handed (as a troop of Benjamites are in 20:16), in line combat, trained left-handers actually have a decided advantage over right-handers, who are taught to fight sword against shield.137 Even so, in interpreting the expression translated “a left-handed man,” it seems best to follow the lead of the LXX’s amphoterodexios, and interpret Ehud’s condition and that of the Benjaminites in 20:16 as “ambidextrous,” that is, skilled in the use of both hands. The meaning is fleshed out in 1 Chronicles 12:2, which describes a group of Benjamites, relatives of Saul who defected to David, as “armed with bows” and “able to shoot arrows or to sling stones right-handed or left-handed.”

Ehud had made a double-edged sword (3:16). This sword was double-edged to facilitate a straight stab rather than a hacking stroke and to slice cleanly into the king’s flesh. Because the present text uses the term gōmed, which occurs only here, it is not clear whether this dagger was a full cubit in length or a fraction thereof. If gōmed is the length of the ʾammâ (“cubit”), then the weapon was approximately eighteen inches long. The length of a cubit is generally thought to be the distance between the elbow and the finger tips in an adult male. Since this distance varies from person to person, it is not surprising that scholars have had difficulty establishing precise definitions of the cubit.

Elsewhere in the ancient Near East the length of the cubit was determined either on the basis of fingers (a twenty-four-finger cubit is common, but a thirty-finger cubit was also used in Babylon) or palms (the standard cubit being five handbreadths and the royal cubit being six (cf. Ezek. 40:5).138 Since most men were right-handed, the weapon would have been worn on one’s left side. Being ambidextrous Ehud fastened the dagger under his garment to his right hip, where no one would suspect it.

Tribute (3:17). In the Old Testament this term is used most often of gift offerings made to God as an expression of gratitude and reverence, but it is also used for a voluntary gift of homage (Gen. 32:14, 19, 21) or political friendship (2 Kings 20:12). Here it applies to the tribute required of a vassal by a superior.139 The present text does not describe the nature of the tribute. The most valued items were precious metals, silver and gold,140 but other items were often included. The following excerpts from the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III of Assyria illustrate this fact:

I received the tribute of Sûs, the Gilzânean: silver, gold, tin, bronze vessels, the staffs of the king’s hand, horses, (and) two-humped camels.

I received the tribute of Jehu (the mans) of Bīt Humrî: silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden goblet, golden cups, golden buckets, tin, a staff of the king’s hand, (and) javelins(?).

I received the tribute of Egypt: two-humped camels, a water buffalo (lit. “river ox”), a rhinoceros, an antelope, female elephants, female monkeys, (and) apes.141

The fact that Ehud was accompanied by an unspecified number of other men who carried the tribute suggests a payment in kind, as in Mesha’s tribute to Ahab in 2 Kings 3:4, rather than only silver and gold.

Idols near Gilgal (3:19). Elsewhere in the Old Testament, the word p esālîm always denotes sculpted pagan cult images, but this ill-suits the present context. By itself the word means simply “carved images [of stone].” Here it seems best to interpret these objects as stelae either marking the boundary of the territory claimed by Eglon or as a monument to a battle by which Eglon achieved control over this region, perhaps analogous to the rock of Ebenezer commemorating the Israelites’ victory over the Philistines in 1 Samuel 7:12142 or the Mesha Stele commemorating Mesha’s victory over the Israelites.143

Outside Israel such markers often contained the following features:

• They were made of stone.

• They were inscribed with text.

• They often contained sculpted imagery that complemented the text.

• The inscription closed with curses on any who would damage or deface the monument.

• The monument was erected in a public place for public observation.

• Royal monuments commemorated achievements emblematic of the king’s role, such as military victories or building projects.

• Royal monuments were treasured as trophies by victorious opponents.

• After the death of the king the monuments served as his memorial.144

It is easy to imagine that these p esālîm were intended for some such function.

Attendants (3:19). This is a technical expression for courtiers of the king, those who have official access to his presence. These could include his ministers, advisors, and bodyguards, charged with securing the safety of the monarch. Ancient Near Eastern kings seem to have employed such guards as a matter of course.

Upper room (3:20). This phrase is generally interpreted something like “cool roof chamber,” based on the obvious meaning of the first word (“upper”) and a derivation of the second from the root qrr (“to be cold”).145 In ancient Israel and undoubtedly among the neighbors the house of the wealthy houses often included upper stories to which the family would retreat for the sake of comfort.146 However, Halpern has rightly noted that not only is “cool” not an architectural term; to escape the heat in the southern Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea one does not build upward, but burrows down into the ground. Appealing to Psalm 104:3, which conjoins ʿaliyyôt (“upper chambers”) with hamqāreh, a participle form of a denominative verb derived from qôra ʿ (“rafter, beam”) rather than from qrr, he suggests plausibly that the present phrase means “the room over the beams,”147 that is, the raised throne room.

Porch (3:23). As intimated, the NIV’s “porch” probably involves the pillared portico of the king’s summer residence. In the modest homes of ordinary citizens the pillars held up the ceilings and supported the second floor.148 The statelier the building, the more substantial and decorative were the pillars. Temples and palaces and other stately structures were often designed with porticoes lined by pillars or entryways held up by pillars.

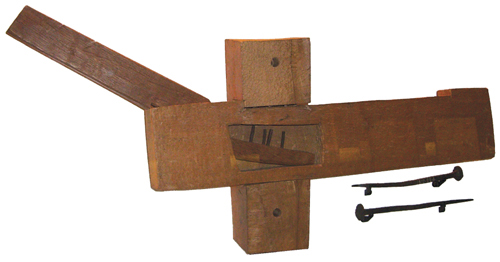

They took a key and unlocked them [the doors] (3:25). The logistics of Ehud’s actions are difficult: How would Ehud escape the throne room if the door were locked from the inside? The answer lies in the nature of locks and keys in the ancient world. See sidebar on “Locks and Keys in the Ancient World.”

Seirah (3:26). The location of Seirah is unknown, but apparently it was in the vicinity of Gilgal.

Trumpet (3:27). The translation of šôpār as “trumpet” conjures up wrong images for the modern reader. This instrument was not made of brass, but consisted simply of a goat or ram’s horn with the cut-off tip serving as the mouthpiece. In Joshua 6:5 this word is interchanged with qeren (“[ram’s] horn”).

The word šôpār seems to be cognate to Akkadian šappāru, which is itself a loanword from Sumerian šegbar (“ibex, wild goat”).149 The šôpār was always used as a solo instrument. Although its range of sounds was limited, the particular character of the sounds it could produce made it an especially important instrument of communication.150

The fords of the Jordan (3:28). Although the Jordan Rift Valley averages six miles wide and at Jericho fifteen miles wide, the river itself is modest in size. The Romans were the first to build bridges across the river. Until then people had to wade across. Except in the rainy season there were many places where this was possible—which is probably why the narrator does not specify where the present fords are.

Struck down about ten thousand Moabites (3:29). On the interpretation of seemingly inordinately high numbers in Judges, see comment on 1:4.

Shamgar son of Anath (3:31). The name of this deliverer is a riddle. Since the Hebrew vocabulary (like that of most Semitic languages) is based on triliteral roots, the presence of four strong consonants š-m-g-r suggests he was not an Israelite.151 The presence of analogous forms of the name in Nuzi texts suggests he may have been a Hurrian mercenary.152 Equally puzzling is his characterization as ben ʿAnat (“son of Anath”).153 In the past interpreters have assumed this meant Shamgar was a resident of Beth-Anath in Galilee.154 Now it seems more likely this is a dedicatory expression: Shamgar was devoted to the service of Anath.155

What this means can be learned from extrabiblical sources. In Canaanite mythology Anath was at the same time the consort of Baal and Canaanite goddess of war.156 But the fame of Anath extended far beyond Palestine. At the beginning of the Nineteenth Dynasty, she was accepted into the Egyptian pantheon, functioning particularly as the goddess of war and personal protectress of the pharaoh.157

Of special interest is an inscription from the Wadi Hammâmaât dated in the third year of Ramesses IV (1166–60 B.C.), which reads, “ʿprw of the troop of ʿAn[ath] eight hundred men.”158 On the assumption that the same Egyptian troop had fought against the Sea Peoples during the reign of Ramesses III (1198–1166 B.C.), Shupak suggests that Shamgar may have been one of these ʿprw (ḫabiru), among whom were found a variety of ethnic elements, including Hurrians. As a member of an ʿApiru troop of mercenaries in Pharaoh’s army named after the Canaanite goddess of war and as a man of valor, Shamgar bore the widely used military cognomen, ben ʿAnath.159 Since at first the Sea Peoples’ base of land operations in Palestine was located in northern Lebanon and the Song of Deborah associates Shamgar with problems in northern Israel, the latter’s confrontation with the Philistines probably occurred in the north at the beginning of the twelfth century B.C. As an officer under the command of the Egyptian pharaoh, Shamgar ben ʿAnath was not intentionally serving Israelite interests.160

Six hundred Philistines (3:31). On the Philistines see comment on 3:3.

Oxgoad (3:31). This word occurs only here in the Old Testament, but in postbiblical Hebrew it identifies a guiding instrument, a pointer (m. Sanh. 10:28a). The present instrument, normally used to train and control livestock, was made of hard wood and probably tipped with metal.