As civil wars or other internal chaos ended in the aftermath of the Cold War – either through peace negotiations, military interventions or national uprisings for regime change – and notwithstanding the distinctive characteristics of each particular case, countries, often cajoled by foreign interveners, entered into a path of peace, stability, and prosperity.

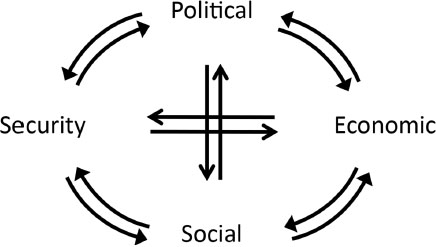

The key challenge of such transition is to prevent the recurrence of hostilities, that is, to make the transition irreversible. This entails the complex task of addressing the root causes and consequences of the conflict. All aspects of this transition are closely interrelated and reinforce each other:

Failure in any one of these areas will put the others at risk. Planning, management, coordination, and financing of this multi-pronged transition are highly burdensome. Given the state of countries coming out of protracted conflicts, the international community [foreign interveners] will need to provide financial aid, technical assistance, and capacity building at every stage of the transition. … Inadequate mandates, insufficient expertise, poor governance and lack of legitimacy have been present to different degrees in all recent experiences with post-conflict reconstruction.1

Academic and policy debate, the media, and the academic literature have largely focused on the security, political, and social transitions to the neglect of the economic one. This is despite the fact that the economic transition is fundamental for the others to succeed since peace has serious economic consequences, as Keynes posited in the aftermath of World War I.

Failure to create viable economies and give former combatants and other groups affected by the war a stake in the peace process has been a major reason for the disappointing record with peacebuilding in the aftermath of the Cold War. A “peace dividend” – including better living conditions, a rewarding job, and reconciliation with former enemies and neighbours – has proved necessary, if not sufficient, for peace to be long-lasting.

Although this book focuses on the economic transition itself, to understand the challenges and constraints under which such transition takes place, it is necessary to cursorily analyze the other simultaneous transitions to describe what each one entails and what the interactions among them may be. Many of the experts and decision makers dealing with the other transitions often make their recommendations without taking into account what such recommendations mean to the economic and financial situation of the country, or to the country’s dependence on foreign aid.

More worrisome, despite the close interconnectedness, both analysis and policymaking largely proceeded with a “silo mentality”2 – that is, with each transition discussed in isolation by their respective experts – rather than in an integrated manner, given that the issues are by no means independent of each other.

In fact, they do interrelate in complex and convoluted ways, as Diagram 2.1 shows in the section on “Interrelations.” Despite it, diplomats, security, and human rights experts often roll their eyes at even the mention of economic issues. At the same time, economists are not generally interested in countries that have such little impact on the global economy and where the problems may be “too political” anyway.

But, as President Clinton famously noted at Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 30 July 1999), “It is not enough to end the war; we must build the peace” – and this cannot be done with a silo mentality. This chapter will discuss the complex, challenging, and multidisciplinary transition from war to peace (Table 2.1) and the various interrelations among the different aspects of it which require an integrated approach if peacebuilding efforts are to succeed. The economic transition will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

Table 2.1 Transition from war to peace

| Transition | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Security | Violence and insecurity |

• Improving public security; • Creating or improving security institutions (civilian police + army). |

| Political | Lawlessness and political exclusion |

• Developing a participatory, fair, and inclusive government; • Promoting respect for the rule of law and for human, property, and gender rights. |

| Social (national reconciliation) | Sectarian/ethnic, religious, ideological or class confrontation |

• Promoting national reconciliation to reintegrate war-affected groups into society and rebuilding the social fabric of the communities after civil war or other chaos; • Developing an institutional framework to address differences through peaceful ways. |

| Economic (economic reconstruction, economics of peace, political economy of peace) | Ruined and underground war economies, state-controlled policies and large macroeconomic imbalances |

• Establishing a basic macro/micro framework; • Rehabilitating infrastructure and services; • Creating a viable economic environment for rural development and entrepreneurship; • Eradicating illicit activities (drugs/corruption). |

The security transition

As Secretary-General Kofi Annan noted in 2004, “Unlike inter-states war, making peace in civil war requires overcoming daunting security dilemmas. Spoilers, factions who see [peace] as inimical to their interest, power, or ideology, use violence to undermine or overthrow settlements.”3

Ideally, violence must surrender and public security must improve before countries can fully engage in the reactivation of their economies. Different analysts have noted how security is the foundation on which progress in other areas rests;4 that security must be put first, since all recovery will prove futile in a chronically insecure environment, and resources will be squandered and can even be hijacked by violent power-seekers;5 and that efforts of donors and national actors (governments, the private sector, and communities) will not succeed otherwise since insecurity lowers the return on donors’ projects and distorts domestic actors’ incentives.6

UN peacekeeping operations, NATO, or occupying forces time and again provide basic support to enforce cease-fires, disarmament and demobilization of former combatants, as well as other confidence-building measures that are necessary to improve security in the short run. However, peacekeeping operations and foreign forces have often remained in the country for long periods at great cost for the international community, with Liberia and Afghanistan being infamous examples. Yet for stabilization to be lasting, indigenous actors must ultimately bear the responsibility for providing security.7

To establish minimum security requires tough legislation, a reformed military force under civilian control, an active and well-trained civilian police force, and an effective judiciary. Although such reforms usually take a long time, without a rapid move in this direction, addressing the problems of violence, impunity, and human rights violations will not be possible. The financial costs of these reforms are often large and hard to finance.

Despite such reforms, security conditions will not be optimal at all times. In fact, many peace transitions have taken place, or are currently taking place, under security conditions that are far from ideal, often with large parts of the territory outside the control of the authorities. This is true of the ongoing transitions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Nevertheless, efforts to improve security should always be at the top of the post-conflict policy agenda and be a priority for national leaders and foreign interveners alike.

In addition to the difficulties of reactivating the economy without minimum levels of security and the large cost of the security transition, there are other problems relating to this transition that need to be taken into consideration in any peace strategy. Failing to do so put the whole peace process in peril.

Perhaps the most important problem relates to the vicious circle created by delays in creating appropriate security forces, resulting in weak governance, lack of legal investment, drug production, insurgency and terrorism, and higher insecurity nationally, regionally, and even globally. This is why moving away from the economics of war to the economics of peace is critical to the transition (Chapter 3).

As the US Army and US Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual notes, in insecure areas of a country controlled by the insurgency, “considerable resources are needed to build and maintain a counter-state.” Because of governance failures, the insurgency often provides basic services and infrastructure as well as means of livelihood to the population of those areas, which obviously has serious financial implications for them. As the Manual points out,

Sustainment requirements often drive insurgents into relationships with organized crime or into criminal activity themselves. Reaping windfall profits and avoiding the costs and difficulties involved in securing external support makes illegal activity attractive to insurgents. Taxing a mass base usually yields low returns. In contrast, kidnapping, extortion, bank robbery, and drug trafficking – four favorite insurgent activities – are very lucrative.8

Although the Manual uses the FARC (Spanish acronym for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) as an example, it could have used the case of Afghanistan which provides a perfect illustration of this point. As foreign minister Abdullah wrote in the Washington Post in October 2002, almost a year after the Bonn Agreement, delays in creating a national army and police forces led to an incipient sprouting of the insurgency. By mid-2003, as security deteriorated further, it became obvious that the belief that the Taliban had vanished had been wishful thinking. Security experts have attributed Taliban early gains to the failure of the government to provide effective police protection. This in turn created major obstacles to economic reconstruction.9

At the same time, there is always some kind of economic activity that can prosper, even in unstable situations. People need to eat and trade (or barter) and hence some of these activities will have to take place in such areas. What kind of support they need, however, should be the focus of a debate, which so far has been missing. One thing is clear: what was labelled “expeditionary economics” – using foreign military forces for economic reconstruction and improved governance in insecure areas – has usually been expensive and futile in chronically insecure environments. Gaining “heart and minds” while bombing at the same time has not proved a good recipe.

Operating under the expeditionary economics mode, the US government created provincial reconstruction teams (PRTs) – consisting of a mixture of civilian experts and military officers – to provide humanitarian and reconstruction support in insecure areas in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military commanders had plenty of money to spend and, as one commander put it, “we thought that by throwing as much money as possible to the problem, we would get it solved.” This created serious price distortions and promoted corruption. Moreover, it created the resentment of inhabitants of more secure areas which received much less support by behaving well.10

The US oversight bodies have collected plenty of evidence on the problems of the PRTs in countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq.11 They have also collected extensive evidence that US investments – particularly in large infrastructure such as dams, power plants, and others – have gone to waste in insecure areas.12

The political transition

Whatever the political solution reached, the transition involves the passage from some kind of oppressive, autocratic and exclusionary regime to a more inclusive, pluralistic, and participatory system based on the rule of law; respect for human, property, and gender rights; transitional justice; and improved governance.

War-torn countries, as any other country, will choose their political leaders and develop their institutions, policies, and governance influenced by a number of historical, cultural, religious, ethnic, or other local idiosyncrasies. Contrary to countries unaffected by violent conflict, however, the political transition in war-torn countries will normally take place amid large foreign intervention and donor-imposed political and economic conditionalities. The latter is the consequence of the large dependence on foreign aid and peacekeeping forces or foreign troops that most of these countries have in the transition. It is in this way that issues of sovereignty and ownership frequently become blurred under such conditions.

Indeed,

Peace agreements often dictated the terms for the interim and/or transitional arrangements. As the new authorities – be they interim, transitional, or elected – assumed power, they had to consolidate their legitimacy, something that proved extremely difficult in most cases. With whatever legitimacy they had and whatever territory they controlled at the time, governments needed to provide security, justice, human rights protection, and basic services and infrastructure to the population. They also had to carry out stabilization and reform for the reactivation of the economy and for the effective utilization of aid.13

Nobel Laureate Roger Myerson’s work is pivotal to understand the challenges of the political and economic transitions in war-torn countries, as well as to design and carry out more effective foreign interventions going forward. Based on his theoretical work in game theory, which he has applied to such transitions, Myerson argues that foreign interveners should take account of the political nature of the state that is being built. Because the state is a political system that puts some people into positions of power and induces the rest of the nation to accept their authority, the feasibility and financial cost of a stabilization mission will depend critically on the way that the state distributes power (which in war-torn countries includes economic aid).14

In Myerson’s view, “The interim leader’s ability to build the first national patronage network after the intervention can become a decisive advantage over all potential rivals. Thus, in handing ‘interim’ … authority to one leader, the foreign interveners may be effectively choosing the long-term leader of the nation.”15 This fits perfectly the political transition in Afghanistan.

As Myerson points out, “when foreign forces help to defend the authority of a state, its national leaders have more incentive to centralize political power narrowly around themselves. But such centralization can alienate key local leaders and so can substantially increase the need for costly foreign efforts to maintain the states.”16

Centralized regimes please donors that find it convenient to have one strong national leader who is empowered to work with them in all the countless complications related to their intervention. In Aghanistan, for example, such a centralized system was alien to Afghans. In it, provincial councils were not given any autonomous powers, which alienated local leaders not aligned with the government and forced the government in turn to rely more on the foreign interveners to keep the country together.17

Myerson recognizes, however, that once a centralized government is established with foreign intervention – as it was in Afghanistan and also in Iraq – forces against decentralization are strong. Naturally, incumbent presidents feel threatened by potential competition from elected local leaders who could eventually build a good reputation by providing public services and infrastructure to local citizens in an inclusive and effective way. Since one of the problems with reconstruction has been that most of it takes place in the larger cities, decentralization could contribute to the gains from peace being more equitably shared across the country.

At the same time, Myerson notes that in a centralized system the president appoints the provincial/state governors. For this reason, close supporters of the incumbent president also have a strong, vested interest in maintaining such centralization on the expectation of becoming governors or mayors at some point.

Successful stabilization, as Myerson argues, depends on the new regime developing a political network that could distribute power and patronage throughout the nation. Although the word “patronage” is often used disparagingly, Myerson uses it with a positive connotation: to acquire and keep its legitimacy, the government needs to allocate its scarce resources fairly across its population through the provision of services, infrastructure, and support of private sector activities. In aid-dependent, war-torn countries, this applies particularly to the distribution of aid. The government requires trusted local leaders to do such distribution effectively and fairly.18

Delays in setting up municipal and other local elections make things worse. Communities in which responsible leadership is lacking and governance is weak are the perfect breeding ground for insurgencies to take root and thrive. By delaying local elections and having fewer promising leaders competing for the presidency, democracy will not prosper. In Myerson’s view, decentralization in the political and economic sense could broaden support for the regime, reduce its dependence on foreign interveners, and make reconstruction more effective in rural areas.19

In Afghanistan, the lack of local political leadership and insecurity in many provinces allowed warlords to continue collecting customs (a major source of tax revenue) and drug profits in areas under their control since Operation Enduring Freedom started in October 2001. Central government’s domestic revenue averaged only 5 per cent of GDP in the first five years, a major obstacle to the implementation of critical peace-related projects and a key factor in the deterioration of security.20

Drawing on the experiences of the DRC and Afghanistan, Jean-Marie Guéhenno argued that the political dilemma was not so much about centralization versus decentralization as it was about how to connect the various levels of government in a cost-effective, transparent, and accountable way.21 By supporting communities financially and technically, donor countries could contribute to improving governance at the local level and also to increase the capacity of the community-level institutions to improving lives and livelihoods in their areas. In his view, to be effective this needs to be done with the approval of the appropriate ministries.

From a macroeconomics point of view, I would argue that it would be difficult as well as ineffective and expensive to finance local governments outside the national government framework. This is because the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs) and other multilateral organizations only deal with national governments. Also channelling funding directly through NGOs, outside the national budget has proved expensive and ineffective. At the same time, governments cannot be expected to make good macro-management decisions without appropriate information with respect to the money that enters the country. At the same time, channelling aid outside the national budget does not contribute to capacity building in the public sector and often leads to a lack of policy ownership, which makes policies unsustainable in the long-run.

For investment and other economic purposes, it is particularly important that governments build up legitimacy, starting as soon as possible during the political transition. Political legitimacy at the national level affects economic policymaking options since uncertainty surrounding the sustainability of economic reform and property rights have been major deterrents to sustainable investment, as in Kosovo and Iraq (Chapter 7).

Political scientists have discussed the problems of having elections too soon. Myerson argues in favour of having local elections as soon as possible. This may help in building up the political credibility of local leaders, which is key for countries with large rural populations.22 In terms of the war-to-peace transition as a whole, national elections in particular often deflect attention from the peace process and politicize it, as happened in El Salvador.23

The social transition

The social transition involves a process of national reconciliation in order to build social cohesion in societies divided by ethnic, religious, sectarian, political, ideological, and/or economic cleavages. After committing atrocious acts against each other, former adversaries are expected to return to the same communities and learn to live together in peace.

As de Soto has pointed out, the UN moved into a new uncharted direction in the post-Cold War era where,

After internal conflict, fighting forces are doomed to coexist under the same roof, and it cannot be taken for granted that fraternal reconciliation will follow fratricidal confrontation. To avoid relapse of internal conflict, channels and institutions – to ensure that future such disputes can be peacefully resolved – must be put in place.24

The institutional framework often includes the creation of civil society organizations, national ombudsmen, and human rights prosecutors. In many cases, for example, El Salvador and Rwanda, “truth commissions” were established to examine the most notorious human rights violations, not only as a catharsis, but also to make recommendations aimed at preventing the recurrence of such abuses. As Helena Meyer-Knapp notes, finding an appropriate way to ease the suffering left behind by the war is a key ingredient of peacemaking and peacebuilding.25

In addition to building trust, improving cohesion, and reintegrating former combatants and other militia, as well as returnees, displaced populations, and other war-affected groups into society in general, these groups must also be reintegrated into productive activities so that they can have a dignified livelihood, a critical task of the economic transition.26

Reintegration – which points to the close interconnectedness of the social and economic transitions – is sine qua non for national and local reconciliation. Such a tremendous challenge requires the effective and inclusive reactivation of stagnant and mismanaged war economies and the prompt rehabilitation of basic services and infrastructure.

Furthermore, reintegration programs require advance planning, bold and innovative solutions, large financial resources, and staying the course with the right policies, frequently for many years. The contrasting experiences of El Salvador and Afghanistan provide stark evidence of things that work and those that are still missing in how the foreign interveners support reintegration.27

The economic transition

The economic transition involves the move away from war-ravaged, mismanaged, and largely illicit economies into stable and viable ones that enable former combatants and ordinary people to earn a decent, licit, and legitimate living.

The economic transition is the much-neglected aspect of the transition to peace. Such neglect is unwarranted and misguided since the economic transition is of fundamental importance in supporting the other aspects of the transition. It is also critical to avoid the aid dependency in which many countries indulge at this time.

That the economic transition takes place simultaneously with the others does not mean, however, that war-torn countries can afford to wait to have security, the elected authorities, the rule of law, the policies and the institutions, the good governance, and the human capacity in place before they engage in production, investment, and trade. Indeed, the economics transition needs to take place within whatever context is in place, and it cannot wait for the foreign interveners to get their act together, or for civil servants to be trained so that they can do it right. Thus, economic policies, institutions, and capabilities will need to adjust as other aspects of the transition improve.

The economic transition needs to begin as soon as possible, not only because this is essential to creating political and social stability, but also because donors are more willing to support peace transitions when countries do their part to ensure their success and sustainability (with the few exceptions often reflecting deep geopolitical interests). This transition is indeed most challenging in the midst of the political, social, and institutional vulnerabilities, the damage to human and physical infrastructure, and the macroeconomic imbalances that are the legacy of conflict.

The economic transition has unquestionably been the least talked-about aspect of war-to-peace transition in donors’ policy circles, in public debate and in academic discourse as well as in the extensive and fast-growing literature on war-torn countries. Most analyses have focused primarily on issues such as creating security forces, establishing the rule of law, strengthening human and gender rights, improving the justice system, and promoting political reform and holding elections.

Interrelations among the four distinct transitions

Although security may well be a precondition for the success of the overall transition to peace, as many experts assert, political reform, national reconciliation efforts, and economic reconstruction will in turn affect the security conditions in the country. This is what – in the economic jargon – is called “reverse causality” and others call a “virtuous circle” or “two sides of the same coin.”28 These terms allude to the fact that the effect works both ways: political reform, national reconciliation, and economic reconstruction may prove futile without security, but security will not take root without progress in those three areas. Whatever one may call this two-way process, it has proved to be critical to a successful transition to peace, stability, and improved welfare.29

Given that policymakers in most countries in a transition to peace cannot rely on adequate and timely flows of aid, effective economic reconstruction is key for political transformation, security reform, and national reconciliation (the other aspects of the multidisciplinary transition) to succeed. Without effective economic reconstruction, peacebuilding efforts will remain elusive.

Indeed, economic policymaking is likely to enhance or go against efforts at national reconciliation. For this reason, every policy should be considered carefully since reconciliation between former enemies has proved sine qua non to preserving peace and stability and promoting prosperity. At the same time, reconciliation programs often have economic and financial consequences that governments and donors might consider a diversion from the overriding need for funding basic services and infrastructure and for creating economic opportunities.

This must not be the case. The rebuilding of a mosque might contribute to stability more as a confidence-building measure for the community than a productive investment may, if that is where the community has set its priority. This, of course, does not eliminate the need for productive investments, but the various needs must be weighed carefully, always taking into account local needs and priorities.

With a few exceptions, the UN has failed to denounce misguided economic policies and misplaced priorities in the transition to peace in countries such as Liberia and Afghanistan. Such policies have excluded the large majority from economic gains (in favour of small domestic elites) and hence are creating increased inequality and sowing the seeds for future conflict. Such policies have often led to rapid but unsustainable growth by failing to create a level playing field for the large majority of men and women, particularly in agriculture on which they largely depend.

By focusing on a misguided “peace through security” strategy in Afghanistan and Iraq, the US government has also ignored interrelationships and reverse causalities. It has basically proceeded as if peace could be established by military means alone. Experience attests to how inefficiencies and lack of progress with respect to the three other areas led in turn to the deterioration of security in both Afghanistan and Iraq, with tragic human and financial consequences both to the countries and to foreign interveners.30

Conclusions

A successful multidisciplinary transition to peace, stability, and prosperity entails improving the well-being of different groups that need to feel part of the peace process and to have an economic and political stake in it. This requires improved security; a more participatory economic and political system; respect for human, gender, and property rights; reconciliation between former enemies; and the reactivation of the economy. The latter is critical to create the income-generating opportunities and improved living conditions necessary to reintegrate war-affected groups into society and productive activities on a long-term basis. Without it, security will not last, reconciliation will not take place, and peacebuilding may be ephemeral.

The UN has yet to recognize the importance of sustainable productive reintegration of former combatants and other war-affected groups as a critical component of peacebuilding. Going forward, the UN must support the creation of viable and inclusive economies in countries in which it has operations if it wants its peacebuilding record to improve.31

Notes

1 Del Castillo, Rebuilding War-Torn States, 15–16.

2 Del Castillo, Guilty Party, 167.

3 United Nations, A More Secure World: Our Shared Responsibility (New York: Report of the Secretary-General’s High Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change, General Assembly document A/59/565), 2 December 2004, 70.

4 Scott Feil, “Laying the Foundations: Enhancing Security Capabilities,” in Winning the Peace: An American Strategy for Post-Conflict Reconstruction, Robert C. Orr, ed. (Washington, DC: The CSIS Press, 2004), 40.

5 Barnett R. Rubin, Humayun Hamidzada, and Abby Stoddard, “Through the Fog of Peace Building: Evaluating the Reconstruction of Afghanistan” (New York: Center on International Cooperation, June 2003), 1.

6 Tony Addison and Mark McGillivray, “Aid to Conflict-Affected Countries: Lessons for Donors,” Conflict, Security and Development, 4/3 (December 2004), 363.

7 See, for example, Feil, “Laying the Foundations: Enhancing Security Capabilities,” 40.

8 David H. Petraeus and James F. Amos, Counterinsurgency Field Manual (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2006, Chapter 1), 11.

9 Abdullah Abdullah, “We Must Rebuild Afghanistan,” Washington Post (October 29, 2002), and Seth Jones, “It Takes the Villages: Bringing Change from Below in Afghanistan,” Foreign Policy (November/December 2010), cited in del Castillo, Guilty Party, 147.

10 For details, see del Castillo, Guilty Party, 220.

11 Operating with less military muscle and much less money, non-US PRTs had some limited success without creating the serious distortions that the US ones did.

12 SIGAR and SEGIR Quarterly Reports to Congress Quarterly Reports to Congress (Washington, DC: several years).

13 Del Castillo, “The Economics of Peace in War-Torn Countries: The Historical Record and the Path Forward,” paper commissioned by UNU-WIDER on the occasion of its celebration of 30 years in development research (Helsinki, 17–19 September 2015).

14 Roger Myerson, “Rethinking the Fundamentals of State-Building,” PRISM 2, No. 2 (March 2011), 91. See also Myerson, “Decentralized Democracy in Political Reconstruction,” presentation at the High Level Meeting of Experts on Global Issues and their Impact on the Future of Human Rights and International Criminal Justice at ISISC (Syracuse, Italy, September 2014).

15 Roger Myerson, “Standards for State-Building Interventions” (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago, mimeo, 2012), 7.

16 Myerson, “Rethinking the Fundamentals of State-Building,” 91.

17 Ibid., 95–96.

18 Ibid., 92–93.

19 For more on decentralization, see Myerson, “Decentralized Democracy in Political Reconstruction.”

20 Del Castillo, Guilty Party, 145–46, 197.

21 Guéhenno also warned that foreigners need to be aware that their promotion of decentralization in countries that are fragile can be misinterpreted as attempts to further weaken or even dismember the country (personal correspondence).

22 Myerson, “Standards for State-Building Interventions,” 8.

23 De Soto and del Castillo, “Implementation of Comprehensive Peace Agreements,” 189–204.

24 De Soto, Foreword in Political Economy of Statebuilding, xviii. De Soto also noted that helping to bring this about will increase the depth and duration of the UN’s involvement. “This was a responsibility that could not be shirked by the Security Council.”

25 Helena Meyer-Knapp, Dangerous Peace-Making (Olympia, Wash.: Peace-Maker Press, 2003), 192.

26 For issues related to productive reintegration, see del Castillo, Rebuilding War-Torn States.

27 For analysis and references, see del Castillo, Rebuilding War-Torn States, 255–272. For the specific problems in Afghanistan, see del Castillo, Guilty Party, 148–153, 192–198, and 243 and footnote 6 (for references).

28 Barnett R. Rubin, Humayun Hamidzada, and Abby Stoddard, “Through the Fog of Peace Building: Evaluating the Reconstruction of Afghanistan” (New York: Center on International Cooperation, June 2003), 18; Marvin G. Weinbaum, “Rebuilding Afghanistan: Impediments, Lessons, and Prospects,” in Francis Fukuyama, ed., Nation-Building: Beyond Afghanistan and Iraq (Baltimore, Md.: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 206), 139; del Castillo, Guilty Party, 148.

29 Perhaps the most complete and interrelated analysis of the four areas of the transition can be found in Paul K. Davis, ed., Dilemmas of Intervention: Social Science for Stabilization and Reconstruction (Washington, DC: RAND, 2011).

30 Del Castillo, Guilty Party, 156–58.

31 Del Castillo, Guilty Party, 149, 243.