3 The economics of war, the economics of conflict resolution, the economics of peace, the economics of development

• Terminology, phases, sequence, challenges, and policies

• Economic reconstruction: the evolving context from the Marshall Plan to the post-Cold War period

One could have thought that with its renowned record of setting the stage for world peace, the Marshall Plan could have established the basis for the economic transition in the post-Cold War period. Although the Plan holds some far-reaching lessons, it took place in a radically different political, security, social, and economic context. For that reason, a new paradigm was required.1

Chapter 3 discusses first the terminology and sequence as well as the main challenges and overriding economic policymaking prescriptions for each stage in the path from war to peace. The chapter then analyzes the differences in the post-Cold War context as compared to the time of the Marshall Plan. Finally, the chapter discusses similarities between countries in post-conflict situations and other fragile countries undergoing development as usual and analyzes how such similarities often lead to their conflation in policymaking – with serious consequences for peacebuilding efforts.

Chapter 4 will then track the contrasting views with respect to many of these issues in the UN and the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs) since the early 1990s.

Terminology, phases, sequence, challenges, and policies

Interchangeable terminology, phases, sequence, and policy challenges

In the economics area, the long-term objective for war-torn countries embarking on the transition to peace, stability, and prosperity is to move out of the underground economy – of illicit, rent-seeking, and mostly unproductive activities that thrive during wars – back onto a path of “normal development.”

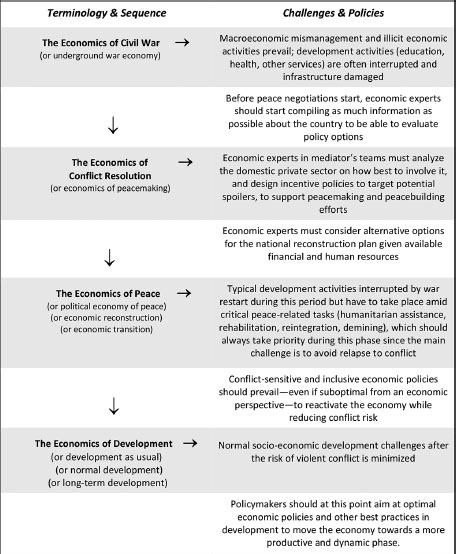

As Diagram 3.1 shows, the term “normal development” is used interchangeably with “the economics of development,” “development-as-usual” or “long-term development,” as it is in the literature. These terms refer to the process that countries at low levels of development – unbounded by deadly conflict – need to embark on to satisfy their basic socioeconomic needs and other aspirations.

But this is a long-term proposition for war-torn countries. To get there, however, such countries need to make peace first and then go through an intermediate and distinct phase: the “economics of peace.” As in the literature, the term “economics of peace” is used interchangeably with “the economic transition” (Chapter 2), “economic reconstruction,” or “the political economy of peace,” depending on where the focus wants to be.2

The four distinct economic phases – the economics of war, the economics of conflict resolution, the economics of peace, and the economics of development – are not necessarily sequential; they often overlap in various and complex ways in different places and at different times. Each has specific challenges and policymaking issues (Diagram 3.1).

Irrespective of the shape the economic transition takes, the overriding short-term objective of the economics of peace phase must be to reactivate investment, increase the provision of public goods, and create employment opportunities for the large majority while minimizing at the same time the high risk that these countries have of relapsing into conflict. This can only be achieved through conflict-sensitive and inclusive macro- and microeconomic policies, targeting the root causes and the consequences of conflict.

The short term objective of the economics of peace is thus fundamentally different from short term relief activities, often carried out for humanitarian purposes to bring minimum levels of consumption to vulnerable populations. There has been much conflation between short-term humanitarian relief and short-term reconstruction, and between the latter and long-term development. Many analysts have failed to distinguish between the strikingly different objectives as well as policymaking challenges and constraints between these phases.3

The economics of peace needs to succeed before development can take root. Doyle and Sambanis make it absolutely clear that peacebuilding is necessary to avoid relapsing into war on the path from peacekeeping to long-term development and that the economic aspects of it have been neglected. In relation to UN interventions they argue that,

Good as UN peacebuilding is in expanding political participation, it has not helped to jump-start self-sustaining economic growth. Economic growth is critical in supporting incentives for peace … and helps achieve war avoidance even in the absence of extensive international capacities. … Thus, narrowing the policy gap between peacekeeping, with its humanitarian assistance, and development assistance, with its emphasis on structural transformation, is a good peacebuilding strategy. UN peacebuilding would clearly benefit from an evolution that made economic reform the additional element that plugged this decisive gap.4

The effective use of economic policies in peacebuilding strategies and in the implementation of peace agreements in this area are often made difficult by the design of the agreements themselves, as Chapter 7 illustrates. That is why particular attention should be paid to the “economics of conflict resolution.”

The fact that peace mediators in general lack economic and financial experts – despite having multidisciplinary teams consisting of mostly political, human rights, gender, justice, and security experts – is perhaps a major factor why peace agreements have been difficult to implement effectively. Particularly lacking in the peacemaking and post-conflict periods are experts on the intricacies of budgetary, fiscal, investment, employment, and financial policies, all of which are key to the effective, inclusive, dynamic, and sustainable economic reconstruction of the country.

A key contribution of an economic expert during peace negotiations would be to identify those that have benefited from the war economy and are potential spoilers so as to design incentive policies to lure them into supporting peacemaking and peacebuilding efforts.

It is indeed necessary to understand the economic factors that fuel the war, to design effective peace agreements and to be able to implement them. In 2000, Mats Berdal and David Malone noted

comparatively little systematic attention has been given to the precise role of economically motivated actions and processes in generating and sustaining contemporary civil conflicts. … There is now much evidence to suggest that the failure to account for the presence of economic agendas in conflict has, at times, seriously undermined international efforts to consolidate fragile peace agreements. … In particular, the tendency … to treat ‘conflict’ and ‘postconflict’ as separate categories and distinct phases in a quest for ‘lasting peace’ has carried with it the expectation (and planning assumption) that the formal end of armed hostilities also marks a definitive break with past patterns of violence. In fact … even in the best circumstances this is rarely the case. Grievances and conflicts of interest usually persist after the end of hostilities and, in turn, affect the ‘peace building’ activities.5

Another contribution of an economic expert during peace negotiations would be to lead a working group with selected representatives of the two negotiating parties and of the private sector to think about how to reactivate the economy and create the sustainable job opportunities and support for startups that have proved essential to sustain the peace. Such a group would have to reach some consensus on the desirable macroeconomic and microeconomic policy framework, on employment, on other aspects of the productive and financial sectors, on institutions and the business climate, on essential services and infrastructure, and on trade and investment relations with the rest of the world. An action plan identifying priorities for the first 100 days and for the first year and how it could be financed would help mediators design more realistic, effective, and implementable agreements.

Most public and policy discussions on peace and the private sector focus on the business sector in donor countries to the neglect of the domestic private sector in war-torn countries and the specific situation of foreign investors in them.6 Because it takes many different forms, talking about the “private sector” as a whole may not make much sense for policymaking purposes. Before involving the domestic private sector – as they should – mediators’ teams must analyze carefully the specific situation on the ground.

The private sector is defined to include in general a variety of businesses willing to engage in risk taking and productive initiatives in formal and informal markets, where profit-making and competition drives production. For peacebuilding purposes in particular, the often large number of farmers in war-torn countries operating mostly at subsistence levels – which may not really fit the typical definition of private sector – should be included in any analysis of the sector.

There are basically four types of investors operating in the private sector: There are domestic investors producing for the internal market and those producing for the foreign market (exporters). There are also foreign direct investors producing for the domestic market and those producing for export.

Because war-torn countries are by no means homogeneous, the four types of investors may not only behave differently in each country, but also across countries. This is because they have different incentives, can benefit from different opportunities, and can create different risks to peace processes. That is why each case needs to be considered carefully. Failing to acknowledge the differences – as it is mostly done in peace processes – as if the private sector were homogeneous within and across countries has created false expectations, inappropriate policies, unimplementable peace agreements, and poor results.

Peace agreements and regime change following military intervention or political upheaval create great expectations. I said it already and it is worth repeating: A peace dividend in terms of better living conditions and rewarding jobs is necessary for peace to be long lasting. If governments fail to reactivate the economy in such a way as to allow for the viable and long-term reintegration into productive activities of former combatants and other conflict-affected groups, disgruntled members of these groups will probably take up arms again.

Without peace, development will not prosper. Thus, although development is the long-run objective, peacebuilding and peace consolidation must be the short-run and intermediate goals until the high risk of violent conflict can be managed.

That war-torn countries have to go through an intermediate phase – the economics of peace – does not mean, of course, that development activities interrupted during the war should not restart and be nurtured as soon as possible. But such development activities require investment, both human and financial, and will take time to have an impact. Education, good health, and improved roads will all be critical to the development of a country and will strengthen peace in the future. In the short run, however, such investments cannot be expected to have a major peacebuilding impact. Expecting that they do – without doing anything else – will likely bring the country back into conflict.

To avoid such a fate, war-torn countries will have to adopt emergency policies promptly and decisively in the early transition to deal with the aftermath of conflict, including the rehabilitation of basic services and infrastructure, demining, and the productive reintegration of former combatants and other conflict-affected groups. Such activities are sine qua non for effective peacebuilding.

Moving away from the economics of war has proved particularly challenging. This requires bringing under control as soon as feasible activities such as drug production and trafficking, smuggling, extortion, money laundering and capital flight, and illegal logging as well as exploitation of minerals and gemstones. Moreover, as Thomas Weiss and Peter Hoffman noted, unusual predatory economic opportunities abound in war-to-peace transitions, including the appropriation of aid for illegal purposes.7

There are many reasons for the urgency of moving away from the economics of war. Illicit, rent-seeking, and highly lucrative activities such as these are an ideal source of finance to insurgencies and terrorist groups, as they are to corrupt national politicians and businessmen. Thus, security stabilization and good governance will be elusive in their presence.

Another reason to move quickly away from the economics of war is to avoid having donors, avid to finance the private sector, end up supporting economic elites of warlords, corrupt officials, and others that accumulated capital illegally during the war and in its immediate aftermath. If this continued, it would entrench poor governance, corruption, and other illicit practices in the post-conflict period, as has happened in Haiti, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Liberia.

However, and despite the urgency, income-earning opportunities elsewhere have to be created before bringing drug production and other such illegal activities under control. This is because poor farmers and other vulnerable groups depend on such activities for food and other basic necessities.8

Unless the economics of peace succeed, war-affected countries will not be able to move into a development-as-usual phase. Moving from one phase to the other has been complex and problematic for various reasons that I will analyze and illustrate with regard to specific countries in Chapter 7.

Confusing terminology across organizations and in the academic literature

The terminology used by practitioners and academics alike has been a constant source of confusion. In general, the term “reconstruction” has been used as a synonym for the multidisciplinary war-to-peace transition as a whole, covering the four different areas. In the economics area, the term “economic reconstruction” means different things to different people and its connotation has even changed over time.9

The term “economic reconstruction” is used to cover war destruction, even though in countries coming out of war in the post-Cold War period much needs to be built rather than rebuilt. The term allows for the fact that countries should not try to recreate policies and institutions of the past that led to the conflict in the first place, although some do, with Liberia being a prime example (Chapter 7). Policies and the new or reformed institutions in the post-conflict period must take into account not only the root causes of the conflict but also the consequences of the war and how these have affected society in general and the economy in particular.

I argue that the terms “reconstruction” or “rebuilding” are preferable to “construction” or “building,” terms that some experts have suggested as preferable.10 The latter give the wrong impression that war-torn countries are tabula rasa and that post-conflict peacebuilding and statebuilding efforts can ignore past institutions and policies.

Moreover, there is a large number of cultural, historical, ethnic, or religious values that are important to the specific countries and their societies and therefore should be reflected in institutional building and policy decisions of both national leaders and foreign interveners. Iraq provides a useful illustration (Chapter 7).11

Different actors often use different terms with the same purpose. For example, the press and many analysts as well as some politicians in donor countries refer to “economic reconstruction” interchangeably with “nation-building” (the construction of a national identity) or “statebuilding” (the construction of a functioning state) or simply “development.”12 The US Department of State prefers the term “reconstruction and stabilization” (or vice versa), and so does the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

The World Bank Group uses the term “post-conflict reconstruction,” and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) refers to the economic transition as “reconstruction and growth” or “recovery and reconstruction.” The UN uses the encompassing term “peacebuilding.” Although Boutros-Ghali referred to “reconstruction and development,” reconstruction has become the aspect of peacebuilding to which the UN pays least heed to. UNDP uses the term “early recovery,”13often conflating humanitarian assistance with reconstruction. Unless it is set in the right context, the term “post-conflict stabilization” can also be confusing, although most of the time it refers to stabilization in the security sense (as used by the US Department of State and military), it can also refer to economic stabilization as used by the BWIs.

Using the terms “economic reconstruction” and “development” interchangeably – as many policymakers, analysts, and institutions often do – conflates the fundamentally different objectives of the two activities and denies the need for strikingly different policies and timeframes in each case. The two may start at the same time as the country moves out of war, but development activities will take time to have an impact, so they may not, by themselves, contribute to peacebuilding in the short term. Quick impact reconstruction policies, on the other hand, can be targeted toward the overriding goal of avoiding relapse.

The two terms also differ with respect to time and duration. While “economic reconstruction” may last ten years or more, it nevertheless encompasses a specific time period, a time period that can be delineated, although with little precision. It usually coincides with the finalization of peace-related programs (often specified in national reconstruction plans) or with the end of foreign combat forces in the countries and the assessment that the probability of relapse is relatively low. The “development” of the country, on the other hand, is a long-term and open-ended proposition.

Economic reconstruction: the evolving context from the Marshall Plan to the post-Cold War period

The definition of the term “economic reconstruction” had to evolve over time because of radically different conditions. Following World War II, reconstruction under the Marshall Plan took place in industrial countries with educated labour forces and with strong political and economic institutions and policy frameworks in place that could easily be adapted to post-conflict economic reconstruction. At the same time, there was no need for reconciliation since, following interstate wars, former combatants return to their countries and do not need to coexist in the same space. For this reason, the term “economic reconstruction” at the time referred mostly to the rehabilitation of basic services and infrastructure for the reactivation of world production and trade.14

By contrast, in the post-Cold War context, economic reconstruction took place in countries at low-levels of development, with young and fast growing populations, with weak policy and institutional frameworks, and with large macroeconomic imbalances. Under such conditions, economic reconstruction required a broader definition: it had to include not only the rehabilitation of basic services and infrastructure destroyed during the war but also the modernization or creation of a basic macro- and microeconomic institutional and policy framework necessary for effective policymaking, for the reactivation of the economy, and for the effective and transparent utilization of aid. Stabilization was necessary to address the large internal and external macroeconomic imbalances of the past and to reactivate the economy.

In the new context, the challenge became creating viable economies on the ashes of war. As wars ended, economies emerged with little income, production, and savings and therefore could not invest, relying mostly on foreign aid even for current expenditures. Because foreign aid15 has been largely scarce, untimely, and/or poorly utilized, these countries found it difficult to create an adequate productive base, to promote reconciliation, and to reduce security instability at the same time, often reverting to conflict.

The problem has not only been underinvestment but also the type of investment. While investment often takes place to satisfy the needs of expatriates and small domestic elites early in the transition, economies will not be viable unless they can provide sustainable work opportunities for the large majority of men and women, particularly the large percentage of youth, typical of these economies, which is both a blessing but also a source of concern because of the demands it creates.16

It was thus that, in the new context, economic reconstruction had to acquire a holistic meaning. It involves activities ranging from the provision of basic health, education, water and sewerage and other basic needs for families and children to the economics of boosting agricultural yields and livestock productivity for small farmers and to the business of getting initial access to capital, technology, and infrastructure for the creation of small- and medium-size enterprises.

Additionally, reconstruction involves the design of policies and institutions targeted at the reactivation of investment, production, trade, and the management of aid. This, together with the need for national reconciliation following intrastate wars, has proved to be a most challenging and expensive proposition.

Contrary to these two experiences, the reconstruction of Korea and Vietnam17 did not fit into either pattern and combined aspects of reconstruction following intra- and interstate wars. A cursory discussion of such experiences is useful to understand the challenges of the last quarter of a century. Both Korea and Vietnam, countries at low-levels of development at the time, did not attempt the political transition towards a more participatory government and remained a single-party system.

The situation with respect to aid was also different. Large US aid supported Korea’s reconstruction. Due to the US embargo, which lasted until 1993, there was no involvement from the BWIs or the Asian Development Bank in Vietnam’s reconstruction. Vietnam also saw a collapse in aid from and trade with the former Soviet Union at the time it renewed efforts at reconstruction by adopting “DoiMoi” (renovation) in the late 1980s.

By contrast, in the post-Cold War context, countries have relied on a large number of donors and other actors. This has created various problems, not only in terms of aid coordination, inefficiencies, and duplication but also as a result of the large distortions created by the unwieldy international presence in the respective countries, which has often been compounded by the large presence of UN peacekeepers or foreign forces.18

In Vietnam, despite the low levels of aid, the country had a major comparative advantage. Although it was a poor country, just as Mozambique, East Timor, Afghanistan, and Liberia, it was strikingly different in terms of education: a mixture of Confucian and Communist influences in Vietnam had resulted in a highly literate population with no gender gap.

Extensive untapped natural resources (oil and gas, coal, gold, gemstones and tungsten), in combination with a relatively educated and low-cost labour force, attracted foreign investment to these sectors. Although resource-rich countries like Liberia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Angola, and Afghanistan always lure foreign investors, the potential benefits in terms of employment generation for the local population are limited as a result of poor education.

Post-conflict economic reconstruction vs. development

Although countries in post-conflict reconstruction share some common features, each one is distinctive, owing to the specific interplay of the many factors that influence the war-to-peace transition. Such factors include the circumstances in which war or conflict began (internal strife, regional conflict, ethnic or sectarian rivalries, or control of natural resources) and the ways in which countries have achieved peace (peace negotiations, military intervention or public upheaval for regime change).

Other factors include the level of development (differences in initial conditions, human capital and absorptive capacities) and the political support as well as the aid and technical assistance that the countries can expect to garner as a result of geopolitical factors. Countries also differ in whether they have a sovereign government and legislature in place, whether the UN (Kosovo, East Timor) has been mandated, or whether an occupying force (the United States in Iraq) has assumed executive and legislative powers.

Since the end of the Cold War, countries in post-conflict economic reconstruction – that is, undergoing the economics of peace – do indeed share a number of characteristics with other fragile countries in the normal process of development, unaffected by war. These are listed in Table 3.1. The similarities between countries in post-conflict reconstruction and others unaffected by violent conflict in the normal process of development have led to a conflation between “reconstruction” and “development.” But there are a number of activities that are peculiar only to “reconstruction.”19

Table 3.1 Characteristics and peculiarities

| Fragile countries in normal development (development challenge) | Countries in post-conflict reconstruction (reconstruction challenge) |

|---|---|

| Human capital and infrastructure in shambles | The same but often worse |

| Macroeconomic mismanagement has led to fiscal and external imbalances that require tough stabilization and structural reform | The same but often worse |

| Lack of transparency; poor governance; corrupt legal, judicial, and police systems; inadequate protection of property rights; incompetent central banks; weak tax and customs administration; and noncredible public expenditure management | The same but often worse |

| Highly dependent on official aid flows, mostly in the form of grants | The same but often worse |

| Protracted arrears on payments on foreign debt; the provision of financial aid is constrained by the need to normalize relations with creditors; often require debt relief on unsustainable external aid burdens | The same but often worse |

| Need to develop a number of capabilities in various areas through training and institutional building | The same but often worse |

| Special needs of post-conflict countries (development-plus challenge) | |

| Need to move away from the war economy | |

| Delivery of emergency aid to former conflict zones (some of which might not yet be under government control) | |

| Disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of former combatants and other armed groups into society and productive activities | |

| Demining (mine clearance) | |

| Return of refugees and internally displaced groups, reintegrating them into productive activities | |

| Rehabilitation and reconstruction of productive assets destroyed because of the conflict | |

| Reform of the armed forces and the creation of a national civilian police. | |

| Access to foreign aid | Access to foreign aid |

| Official Development Flows (ODA) amount on average to 1–10 percent of Gross National Income (GNI), with few exceptions (mostly islands or very small countries). | ODA can spike to 50–100 percent of GNI in the immediate transition from war and fall rapidly thereafter, with few exceptions. |

A critical factor in making peace sustainable – as we have seen most tragically in Afghanistan in the early 2000s and even in Lebanon in the summer of 2006 – is the need to disarm, demobilize and reintegrate former combatants and other conflict-affected groups effectively and permanently into the productive life of the country. This entails a number of activities also detailed in Table 3.1 that make

post-conflict economic reconstruction a development-PLUS challenge: countries emerging from protracted civil wars have to confront the normal challenge of socio-economic development while accommodating, at the same time, the additional burden of reconstruction and peace consolidation.20

This development-PLUS challenge is particularly arduous since, after years of political polarization and ideological or ethnic confrontations, building consensus on macroeconomic policymaking is hard. At the same time, putting the economy back on a path of stabilization and inclusive and sustainable growth becomes imperative to create improved livelihoods and public goods for conflict-affected groups and the resident population in former zones of conflict.

Table 3.1 also shows a major difference in terms of the aid resources available to countries under normal development and those carrying out a development-plus challenge (see also Table 6.1).

Given the basically nonexistent capacity of war-torn countries to rely on domestic savings for investment in the early transition, the controversy over aid during the last few years has wrongly focused on whether aid should be increased or eliminated altogether rather than on how it can be made more effective and accountable.21

The debate has also failed to distinguish between “development aid” on the one hand, and “humanitarian” and “reconstruction aid” on the other. While countries in the normal process of development (with few exceptions) complement their own savings capacity – their main source of development finance – with low but stable levels of development aid, humanitarian and reconstruction aid in war-torn countries usually spikes after the crisis. The large volume of aid (and the concomitant large presence of the international community) not only creates all kinds of distortions in the national economies but also provides a serious challenge to its effective and noncorrupt utilization.

Thus, despite the similarities with other fragile countries pursuing normal development, countries in postconflict reconstruction are clearly distinct – have different needs, different objectives, different risks, and different amount of aid – from those pursuing normal development.

Because of the fundamentally different objectives, policymaking during the economics of peace and during the economics of development must also be fundamentally different, something that the BWIs have taken time to accept, as discussed in Chapter 4.

At the same time, these countries face the challenge of having to utilize large and quickly reversible volumes of aid and, as a result, to deal with the large political and military involvement of the international community. The key challenge in this regard is to ensure that economic policies to reactivate the economy and generate inclusive employment are conflict-sensitive, that is, tailored to do minimal harm to the fragile peace and to rein in spoilers.

Conclusions

Because economic policies are critical to effective peacebuilding, this chapter analyzes the four phases of the transition – the economics of war, the economics of conflict resolution, the economics of peace, and the economics of development – to help the debate of how each can contribute to or derail efforts of war-torn countries to move to a path of peace, stability, and prosperity.

The chapter also establishes the fundamental difference between post-conflict economic reconstruction and normal development. The main objective of economic reconstruction – the economics of peace – should be to avoid the recurrence of conflict, which calls for conflict-sensitive policies and rules out optimal economic policies. This should be so even if the development objectives are delayed or even derailed. Insisting on optimal economic policies in the early transition – as the BWIs often preach – has often resulted in conflict recurrence (Chapter 7).

Notes

1 For a discussion of the Marshall Plan, see Dulles, The Marshall Plan. For a discussion of how the Marshall Plan differs from economic reconstruction in the new context and the lessons for it, see del Castillo, Rebuilding War-Torn States, and Guilty Party.

2 I often use “the economics of peace” as a discipline, “economic reconstruction” to emphasize the broad economic tasks of rebuilding, “economic transition” to differentiate it from the other aspects of the simultaneous transition to peace, and “the political economy of peace” to emphasize political constraints.

3 Sultan Barakat and Margaret Chard point out that in post-conflict situations, foreign interventions are normally led by the short-term relief principle. See Barakat and Chard, “Building Post-War Capacity: Where to Start?” in After the Conflict: Reconstruction and Development in the Aftermath of War (London: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2010), 173.

4 Michael W. Doyle, and Nicholas Sambanis, 2006, Making War and Building Peace (Princeton, N.J. and Oxford: Princeton University Press), 132.

5 Mats Berdal and David M. Malone, eds, Greed and Grievance: Economic Agendas in Civil Wars (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2000), 1 and 9. For other seminal work in this area, see Karen Ballentine and Jake Sherman, The Political Economy of Armed Conflict: Beyond Greed and Grievance (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2003).

6 This was the case, for example, with the Business and the Private Sector groups at the United States Institute of Peace, in which I participated.

7 Thomas G. Weiss and Peter J. Hoffman, “Making Humanitarianism Work,” in S. Chesterman, M. Ignatieff, and R. Thakur, eds, Making States Work: State Failure and the Crisis of Governance (Tokyo: UN University Press, 2005), 299–300.

8 See, for example, various studies done by AREU in Afghanistan.

9 When the economic context is clear, “reconstruction” is used interchangeably with “economic reconstruction” to avoid repetition.

10 David Sedney, a former US deputy assistant secretary of defence, argued along these lines at an event at the USIP (Washington, DC: April 2016).

11 For an interesting analysis of how the United States rightly took into account past budgeting practices in Iraq, see James D. Savage, Reconstructing Iraq’s Budgetary Institutions: Coalition State Building After Saddam (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

12 Even the use of these terms as synonyms is confusing since “statebuilding” and “nationbuilding” are concepts that mean different things to different people. See Carolyn Stephenson, “Nation Building,” in Beyond Intractability, Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess, eds. (Boulder, Colo.: Conflict Research Consortium, University of Colorado, 1 January 2005). Also, although these two concepts are distinct from peacebuilding, people often use them interchangeably. See Jenkins, Peacebuilding. For an analysis on differences between peacebuilding and statebuilding or nationbuilding, see Roland Paris and Timothy D. Sisk, eds, The Dilemmas of State Building (London: Routledge, 2009), 1–20; and Francis Fukuyama, State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004).

13 For more details on the use of these terms by different organizations, see Jenkins, Peacebuilding, 32–33.

14 See Dulles (1993).

15 Unless specified otherwise, “aid” refers to OECD Official Development Data (ODA). See Table 6.1 for definition of what ODA includes.

16 Del Castillo, Rebuilding War-Torn States, 29–30, 22–25.

17 For more details, see del Castillo, “Economic Reconstruction of War-Torn Countries: The Role of the International Financial Institutions,” Seton Hall Law Review, 38/4 (December 2008).

18 For a discussion of the distortions created by an extensive foreign presence in a country, see del Castillo, “The Economics of Peace: Five Rules for Effective Reconstruction,” Special Report 286 (Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace, September 2011), and Guilty Party.

19 Del Castillo, Rebuilding War-Torn States, 30–38.

20 Graciana del Castillo, “Auferstehenaus Ruinen: Die Besonderen Bedingungen des Wirtschaftlichen Wiederaufbaus nach Konflikten,” [“Post-Conflict Economic Reconstruction: A Development-PLUS Challenge”]. Der Überblick (Germany’s Foreign Affairs) (4/2006, December). See also, del Castillo, “Post-Conflict Peace-Building: The Challenge to the UN,” CEPAL Review, 55 (October 1995), 29.

21 Graciana del Castillo and Edmund S. Phelps, “Dead Wrong: If It Is to Become ‘The Next Big Thing,’ Africa Will Need Aid,” Argument, Foreign Policy (6 July 2009).