DISNEY’S CRAZY UNCLE IN THE ATTIC

Southern California, especially Los Angeles, is the great underrated stew pot of American popular culture. Sure, the folks who control the news media and publishing media tend to be based in New York City and therefore center all culture of importance in their hometown, but that just doesn’t hold up under closer examination. For the last century, L.A. is where it’s been at. Just about every major triumphant cultural reference point of any value seems to brewed in that sunlit neighborhood.

I know this is a grand and heretical statement to make. I don’t care. It’s just the facts as I have seem them emerge in my endless studies of graphic design. New York may be where the European influence is most felt in the design world, and it’s certainly where the corporate money dwells in the largest abundance. But, for your true pop movements and pop design language, L.A. is king.

It just is.

The impact of the surreal vision of Walt Disney Studios is a great example. The movie industry is so powerful in forming our collective ideas about ourselves that we tend to ignore it as a pop culture design language source and classify it as “culture itself”—as if cinema is some sort of REAL reflection of our actual lives. Even animation jumped the shark into a shared reality long before CGI became the focal point of virtually EVERY advert in television.

When Disney decided to take the leap of faith into feature-length animation, there were many hurdles they needed to overcome. The histories tend to focus on the technical innovations, but the actual cultural experimentation and exploration get a shorter shrift. I think that’s largely because they were such successful explorations that they became part of the “living dreamscape” of our reality. We can’t see the horizon over our own noses.

One of the truths behind Disney is that they, more than any other single source, introduced Surrealism into the heart of American popular vision. Dancing and singing teapots and comedic mice are taken for granted as reality at this point in our dreams and lives. Many people actually think Mickey Mouse is a real person—just like most people have “learned” that when shot with a gun, people simply fall cleanly to the ground and die peacefully, only to resurrect for another day (movie). Admit it, sometimes even YOU think that’s how it works.

Disney also spent a LOT of time exploring consciousness and other altered states of reality to achieve their vision. Drug use was rampant in the early days. They didn’t have LSD or amphetamines yet, but marijuana was very popular among their art staff and cocaine was also rumored. There are photos of the art team bringing live animals into the studio to sketch, a real party atmosphere.

However, the main man at Disney, the guy who they turned to get the REAL STUFF, was a quiet unassuming elder statesman of surreal dream cartooning. He was an Eastern European gentleman named Albert Hurter. When creating the characters for their first feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, they gave up on trying to conceive the how the dwarves should look and instead asked Hurter to do it. His sketches became the seven little “demons.” His sketches for Snow White also seem to have become the seminal starting point for that character as well.

Albert Hurter (1883–1942) was actually one of several concept sketchers employed by Disney to act as sort of “idea specialists.” In Hurter’s case, he seems to have kept to himself in a back office and just “drew crap” all the time. His English was faltering and he was very mannered and “proper” in old European ways. He lived very frugally and initially couldn’t even drive a car. Later, when his loving and devoted co-workers gave him a car as a gift, he fell in love with long drives and became addicted to endless cross-country trips. He was apparently a terrible driver.

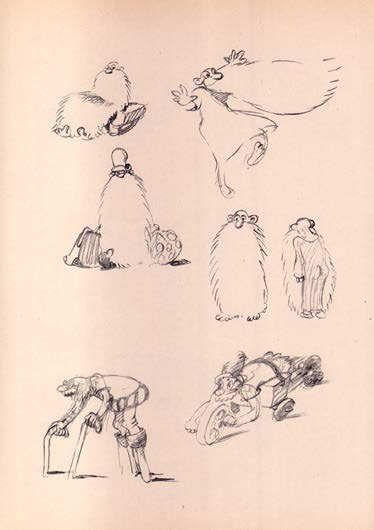

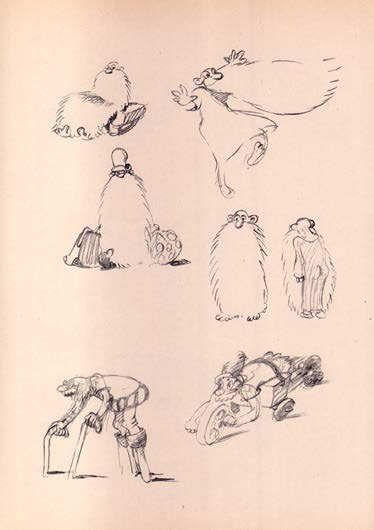

Hurter was the mad uncle in the attic. He sketched anything and everything, often just following his whims. He was much older than the youngsters on staff and they all marveled at his classic drawing skills. Hurter also worked in a cartoon style that could only be called “surreal.” His thinking was so deeply and disturbingly outside any known box that his work was virtually unusable except as inspiration for the more conservative concepts controlled by Disney himself. His work was so powerful and inventive that he seems to be THE major creative visual force responsible for the studio “look,” second only to Walt Disney himself.

Eventually, he took sick and then quietly died. As a tribute to his memory, his co-workers gathered together a selection of images (pages, actually) from his sketchbooks and published them posthumously as a tribute to his genius and their affection for him. Apparently Hurter even left money in his will to allow for the printing of the book. It seems to have been an extremely small private printing and was apparently only distributed among staff. Its subsequent history seems to be one of corporate disapproval.

The book, Albert Hurter: He Drew As He Pleased, is a very rare and expensive book to now collect. Illustrator Scott McDougall found a copy and showed it to me. I immediately photocopied the whole thing. It blew me away. That started a two-decade-long search to find a copy.

One of the things that strikes me about Hurter’s work is how many now familiar and iconic images exist in his sketches in this little book. I assume that this book MUST have drifted through the Los Angeles creative community for some time. There is no way that this stuff did not pass the eyes of some of the underground “geniuses” that later became the lions of the new outsider underground world. Being an industry town, copies of this book were seen and emulated—just like the Disney crew paid him to do, to sketch and inspire.

Why do I point this out? Well, Von Dutch MUST HAVE seen this book. Robert Crumb MUST HAVE seen this book. Roger Corman MUST HAVE seen this book. There are just too many iconographic images later popularized by underground superstars. This book is probably one of the single most influential compilations in the history of subcultural America, and it only seems to have drifted through L.A.

I know, I know. These are really big claims to make, but when you research the history of this Albert Hurter person and look at the contents of this book, and trace the path of the language and icons presented, it leaves you with some questions. This is my answer: This was a hugely influential volume. It was seen and emulated by scores of creative nutjobs who later became iconographic inspirations for American pop culture language. This festering process must have only happened in Los Angeles, the hub of a massive American trash culture wheel slowly turning the rest of the world. Go figger.