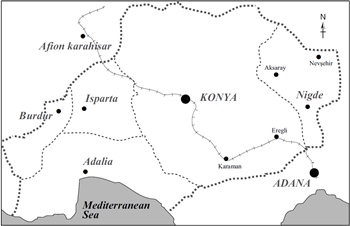

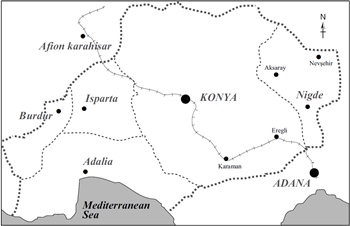

During the deportations of summer and fall 1915, all the deportees from Thrace and western Anatolia who were following the Adabazar-Konya-Bozanti route to exile in Syria were concentrated in the vilayet of Konya. Konya’s train station, which lay on the last trunk of the railway, also served as a transit or regrouping center for the deportees. By the same token, it played a crucial role in the system put in place by the government to expel the Armenians from western Anatolia. An examination of the methods employed here by the local authorities and the CUP delegates sent to Konya offers an opportunity to examine the way the Special Organization and the ministries responsible for the armed forces and police intervened in these operations. This examination is the easier to make because there were around 24,000 local Armenians in the vilayet of Konya, according to the Patriarchate’s statistics (nearly 14,000, according to the Ottoman census),1 even if a large proportion of them were deported as well. The reports by these Konya Armenians, as well as the observations of American missionaries or deportees who spent time in Konya, shed light on the system set up by the Ottoman government.

In the city of Konya, where the vali had his seat, 4,440 Armenians lived in the upper quarter known as Allaheddin. There were also nearly 5,000 in Akşehir, in the northwestern tip of the sancak, somewhat more than 1,000 in Karaman, in the south, and another 1,000 in Eregli, in the southeast.2 Since 6 August 1914, the vali, Azmi Bey, formerly prefect of police in Istanbul,3 had been mistreating the Armenian population of the vilayet and had extorted large sums from it “for the war effort.” In early May 1915, he organized house searches that went on for several nights, especially in the Armenian schools and the homes of notables. Officially, the purpose of these operations was to locate illegally held weapons. In reality, Azmi’s instructions were probably to work up a compromising case against the Armenians in order to justify arresting the Armenian elite here as well.4 On the basis of a list apparently compiled earlier by the local Ittihadist club, 110 merchants, financiers, and elementary schoolteachers were summoned to the police station, then taken to the train station and sent off toward Sultaniye, east of Konya. In the same period, 4,000 Armenian deportees from Zeitun arrived in Konya in a pitiable state, after having trekked through Tarsus and Bozanti with no means of subsistence whatsoever. In an exchange with the vali that took place on 6 May, the chief physician of the American Red Cross Hospital in Konya, Dr. William S. Dodd, asked Azmi for permission to go out to meet these deportees and provide them with food and basic necessities. The vali categorically refused.5 For his part, the Armenian primate, Karekin Khachadurian, went to great lengths to win the deported men the right to return home. He made an appeal to this effect to Azmi, who had just returned from a trip to Istanbul. “The policies adopted with regard to the Armenians,” the vali answered, “cannot now be modified. The Armenians of Konya should consider themselves lucky because they have been deported no further than to a neighboring province.”6

On 18 June 1915, Azmi, who had been appointed vali of Lebanon, was replaced by Celal Bey, who had until then been posted to Aleppo (from 11 August 1914 to 4 June 1915). The result was a shift in the policies of the authorities in Konya. The new governor was a well-meaning man who refused to deport the Armenians of his province. It was while he was absent – he left for “medical care” in Istanbul – that the first convoys of deportees from Adabazar arrived in Konya, around 15 August, after being pillaged on the way. Dr. Dodd, who describes their physical condition, also notes that 2,000 of them had been put in a medrese in Konya and left there without any food at all. “All reports,” he writes in this connection, “that the Government are providing food are absolutely false, those who have money can buy, those who have none beg or starve [...] How many can survive it?”7

The urgent dispatch to the capital of several Syrian divisions forced the authorities to call a temporarily halt to the movements of the convoys of deportees.8 Taking advantage of the fact that Celal was in Istanbul, the local Young Turks hastened to put nearly 3,000 Armenians from Konya on the road on 21 August. Although Azmi had already assumed his new functions in Beirut, indications are that he continued to exert a great deal of influence in Konya.9 Ferid Bey, known as Hamal Ferid, the CUP’s responsible secretary in Konya, organized these deportations. He was assisted by the main Unionist notables in the city: Muftizâde Kâmil Bey, the mayor and president of the Ittihadist club; Haydarbeyzâde Şükrü Bey, the president of the “Committee for National Defense”; Köse Ahmedzâde Mustafa Bey; Akanszâde Abdüllah Effendi; Haci Karazâde Haci Mehmed Effendi; Dr. Rifki, who had been charged with supervising the deportations; Hamalzâde Ahmed Effendi; Momcizâde Ali Effendi; Şükrüzâde Mehmed Effendi; and Dr. Servet, who had been responsible for the massacre of the worker-soldiers in the amele taburis.10 Among the state officials from whom he received support were Edib Effendi; Rifât Effendi, the secretary general in the town hall; Mehmed Effendi, the registrar; and İsmail Hakkı, the head of the Régie. Ali Vasfi, the head of the office of military recruitment; Saadeddin, the police chief; and Hasan Basri, the assistant police chief, carried out the deportation procedures.11 The most active among the notables, especially in the seizure of Armenian assets, were Hacikarazâde Haci Bekir Effendi; Molla Velizâde Ömer Effendi; Kâtibzâde Tevfik Effendi; Ruşdibeyzâde Mustafa Effendi; Allaeddin Ağa; Mustafa Ağazâde Bedreddin Effendi; and Hacikaransinoğlu Deli Ahmed Effendi.12

In the few days that preceded the departure of the first convoy from Konya, the city was transformed into a marketplace. Improvised sales took place everywhere. Often, the city’s Turkish inhabitants went to inspect the Armenians’ houses and suggested that their owners give them their belongings, for which they would have no further use, “since [they] would be left alive, at best, only a few more days.”13 Archbishop Khachadurian, accompanied by the Reverend Hampartsum Ashjian, sought in vain to bring the commanding officer of the German contingent stationed in Konya to step in. Even the American missionaries could only stand by helplessly and watch as the Armenian presence in Konya was wiped out. The committee responsible for “abandoned property” laid hands on the deportees’ houses and arranged the transfer of bank accounts and the precious objects they had deposited with the banks before going to watch the demolition of the Armenian cathedral ordered by a çete leader, Muammer.14

A second convoy, comprising the last 300 Armenian families from Konya, had been assembled at the railway station and was ready to set out when the vali, Cemal, returned from Istanbul around 23 August. Saved by his intervention, these families were given permission to return to their homes, which had already been stripped of a good deal of their furniture. For as long as Cemal held his post – that is, until early October – these people remained in Konya and, side-by-side with the American missionaries, rendered great service to the tens of thousands of Armenians from the western provinces who passed by way of Konya’s train station. As soon as the vali was transferred elsewhere, they were deported in turn, on the initiative of the CUP’s responsible secretary, Ferid Bey.15 It is, however, noteworthy that lists of people to be exiled were regularly drawn up beforehand and Celal was unable to prevent them from being deported.16 In this regard, Dr. Dodd writes, “The vali is a good man but almost powerless. The Ittihad Committee and the Salonika Clique ruel all. The chief of Police seems to be the real head.”17

The Kaza of Karaman

In line with the schedule of anti-Armenian operations observed elsewhere, the houses of Karaman’s Armenians were subject to police searches on Sunday, 23 May 1915, and a number of men were arrested. The operation was organized and overseen by the local Unionist club, which was under the control of the mayor, Çerkez Ahmedoğlu Rifât, Helvadızâde Haci Bekir, and Hadimlizâde Enver. An enormous bribe paid out to the Young Turks nevertheless made it possible to limit the number of men who were “sent away.” The veritable deportation of the Armenian population was not set in motion until 11 August 1915. The convoy took the Eregli-Bozanti-Tarsus-Osmaniye-Katma-Aleppo route and eventually reached Meskene in the Syrian Desert. Armenian property in Karaman was pillaged immediately after the deportees’ departure.18

The Kazas of Akşehir and Eregli

In the principal town of the kaza of Akşehir, also called Akşehir, which had a big Armenian population, the deportations began on 20 August and went on until October. The members of the first convoy, after traveling a short distance by rail to Eregli, where the kaymakam, Faik Bey, the police chief, İzzet Bey, the commander of the gendarmerie, Midhat Bey, and Mustafa Edhem Bey stripped them of their belongings, continued their journey on foot as far as Osmaniye. They were left there until 23 October and were then sent off to Katma and the Syrian deserts. Of Akşehir’s 5,000 to 6,000 Armenians, 700 were allowed to remain in the town. In 1919, there were, furthermore, 960 survivors, almost all of the women and children who had been abducted: three hundred were in Aleppo, 460 were in Damascus, and 200 more were scattered throughout Syria. One hundred young girls were also held by families in Akşehir.19

As elsewhere, the CUP’s responsible secretary, Haydarbeyzâde Şükrü Bey, and his local henchmen, Kürd Topal Ahmedoğlu Ömer and Fehmi Effendi, the müdir of the nahie of Cihanbey, played decisive roles in expelling the Armenians of Akşehir. They had the active help of government officials, above all Ahmed Rifât Bey, the kaymakam; Kütahyalı Tahir, the director of the Agricultural Bank; Nâzım Bey, a magistrate; İzzet Bey, a Treasury official; Hasan Vasfi Effendi, the police chief; Ömer Effendi, the kaymakam’s secretary; Kâmil Effendi, the head of the Telegraph Office; Rifât Effendi, the secretary general of the municipality; Kâmil Effendi, the director of the Turkish orphanage; and Mehmed Effendi.20

When Reverend Hans Bauernfeind passed through the Eregli train station on the afternoon of 23 August 1915, he observed that “everything here is simply terrible. Armenians are camping without shelter by the thousands; the rich have lodgings in town ... They do not suspect the imminent danger [they are in].”21 The 1,000 Armenians of the Eregli community had been dispatched toward Syria a few days earlier by the kaymakam Faik Bey; the police chief İzzet Effendi; Yusufzâde Nadim, the head of the Office of Deportations; and Major Hasan Bey, the military commander of Ulukışla.22

The Deportations in the Sancaks of Burdur, Niğde, Isparta, and Adalia

In 1914, the Armenian presence in this sancak in the southwestern part of the vilayet was concentrated in Burdur (pop. 1,420).23 Toward mid-August, the mutesarif, Celaleddin Bey (who held his post from 23 April 1915 to 27 August 1916) summoned the vicar, Father Arsen, and informed him that he would have to leave the city with his flock in 24 hours. The Armenians’ property was confiscated on the spot and sold off for next to nothing. The convoy was first sent to Konya, where it remained for two weeks on the premises of the Sevkiyat (the organization responsible for carrying out the deportations), while a political battle raged between Celal Bey, who was trying to have the Armenians sent back home, and the police chief, Saadeddin, a Unionist, who ultimately obtained permission from Istanbul to deport them. By foot or rail, these 1,000 deportees traveled through Rakka and Ras ul-Ayn and were then sent in the direction of Der Zor. By January 1919, only seven families were still alive.24 Haci Ahmed, the president of the local Ittihad club; Major Murad Bey, the head of the recruitment office; and Mehmed Bey, the police chief, helped the mutesarif conduct these operations.25

In the prefecture of the sancak of Niğde, 1,500 Armenians made a living as stockbreeders. Located close by, Bor had an Armenian population of nearly 900; 1,500 Armenians lived in Aksaray, located in the northern part of the sancak; perhaps another 2,000 lived in Nevşehir. The total Armenian population of the sancak was thus over 6,000.26

Bauernfeind, who traveled through Niğde on 22 August, noted that the Armenians “had all been sent into exile” and observed the same thing in Bor. On the way, he came across a group of Armenian men. “Even the young, intelligent çavuş accompanying us,” the Protestant minister wrote, “shares the view that they are all going to be killed.”27 Nazmi Bey, the kaymakam of Niğde, and Lieutenant-Colonel Abdül Fetah, the head of the deportation office in Aksaray, organized the massacres in Aksaray in late August.28 The Armenians of Nevşehir were deported to Syria in mid-August 1915 by the kaymakam Said Bey, who held his post from 17 April 1914 to 17 November 1915.

The 200 Armenians of Adalia, the 500 of Elmaly, and the 1,180 of Isparta were spared, possibly thanks to the mutesarifs of Adalia, Kâmil Bey (who held his post from 3 September 1913 to 3 April 1916), and Isparta, Hakkı Kilic Bey (who held his post from 5 November 1914 to 28 December 1915).29

According to Dodd, the many Çerkez living in the province were the backbone of the squadrons of çetes who harassed, pillaged, and massacred the deportees in the convoys that crossed the region on their way to Bozanti.30