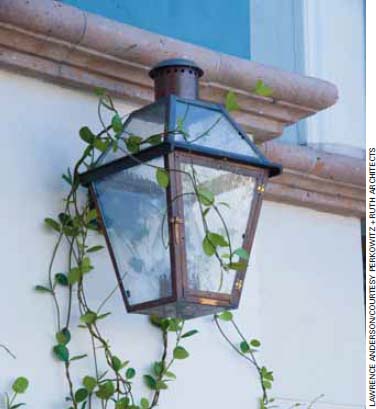

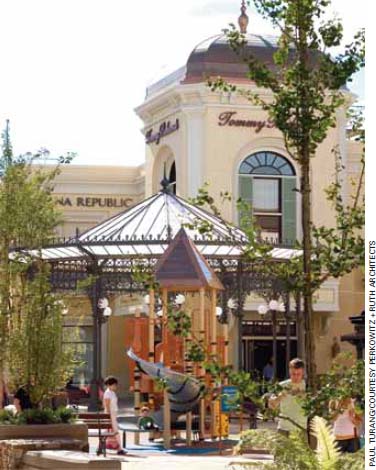

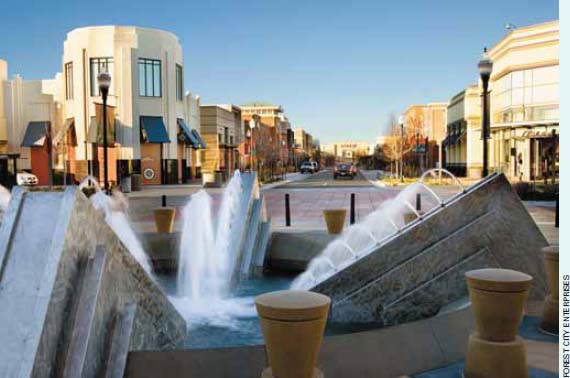

The master plan for Victoria Gardens is based on an elaborate story-board for how a downtown might have developed organically in Rancho Cucamonga, California. Intended to add texture, color, and interest to the project, not to fake a historic setting, the plan clearly depicts Victoria Gardens as a new project.

Over the past decade, a new retail DNA has evolved. No longer dominated by enclosed regional malls surrounded by seas of parking, the new retail model is decidedly more open, more integrated, and more lifestyle oriented. Many of the original rules of retail development still hold true, but today’s developers and designers are gradually changing them to embrace an evolving marketplace for the new millennium.

The most obvious change is the decrease in quantity of developable sites. The traditional mall developer has been forced to rethink the meaning of the old—and still true—adage “location, location, location.” Many existing centers are getting a makeover, adapting to trends and building in greater flexibility for future change.

These trends are being driven by lifestyle—a frequently used word that has come to mean many things to many people. At its core, “lifestyle” refers to consumers’ choices and the environments in which they spend their time. Today’s shoppers are searching for more than simply products in a convenient setting; instead, they are looking for more meaningful relationships with their shopping environments—places that respect and inspire their decisions.

From the details (pedestrian-friendly, open-air streets with well-defined and designed public areas) to the mix (anchors that are not necessarily department stores but might be big boxes, entertainment offerings, clustering of like uses, and well-programmed public areas), this new appreciation for lifestyle is increasingly seen at every level of design. Perhaps most important, this new generation of shopping centers is making better connections with consumers’ environments—where they work, live, and play—and becoming a more tightly woven component of their everyday activities. Altogether, these elements create environments where consumers choose to spend more of their time.

The key to understanding today’s shoppers no longer lies solely in demographics. Instead, psychographics now reigns supreme, predicting consumer behavior not only on socioeconomic standing but also on likes and dislikes, expressions, and aspirations. Even the qualities these shoppers do have in common have changed: turned off by traffic and long commutes, they expect shopping to be close to where they live and offer the convenience of accomplishing many things in one visit; they seek more diverse dining and entertainment options (and have researched those options), and they look for authenticity in their environments.

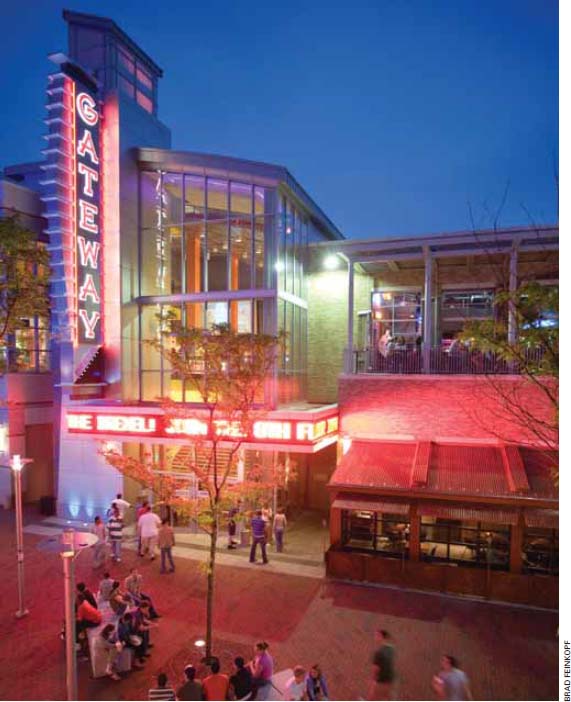

The lively design of West Hollywood Gateway in West Hollywood, California, creates a shopping destination.

Along the same lines, today’s shoppers look at urban-style density for precedents to the kinds of environments they crave. Even those who live in suburban areas seem to favor development that captures the vitality of urban streets (or the suburban version of urban streets), the convenience of public transit connections, and quick and easy pedestrian links to other development. Smart growth initiatives have bolstered this trend, offering incentives for developers looking to create urban-style infill projects.

Since the end of the 20th century, technology has continued to influence the shopping environment. Although the growing popularity of the Internet and online shopping has certainly changed traditional brick-and-mortar retailing, it has not—and will not—replace it. Instead, it has forced developers, designers, and particularly retailers to explore new ways to draw customers and to market and sell merchandise. Mobile technology and automatic identification tagging allow retailers to target with laserlike precision specific consumers based on buying patterns, demographics, and psychographics—or simply because a shopper carrying a mobile phone happened to walk by a “hot spot.”

Retailers are getting better all the time at implementing effective multichannel merchandising strategies aimed at integrating and exploiting the best of the bricks, clicks, and pics (catalog) channels. Today, thanks to distributors like Amazon.com and eBay, consumers have access to many more products, all available all the time at multiple price points.

Wide sidewalks and generously landscaped courtyards at West Hollywood Gateway contribute to establishing the area’s pedestrian-friendly character.

With all these factors influencing the retail environment, how has it changed? And more important, how does it need to continue to change to stay competitive and continue to attract today’s savvy consumers? It starts not with what is changing but with what is not: the absolutes of shopping center development and design. Reflecting decades of trial and error, these retail truths prove that some rules are meant not to be broken:

Once these tried-and-true rules have provided the foundation for a shopping center, developers and designers can begin to explore products that will capture today’s market. In other words, once the old rules are understood, the new rules can begin to govern how developers can create a fresh, competitive environment:

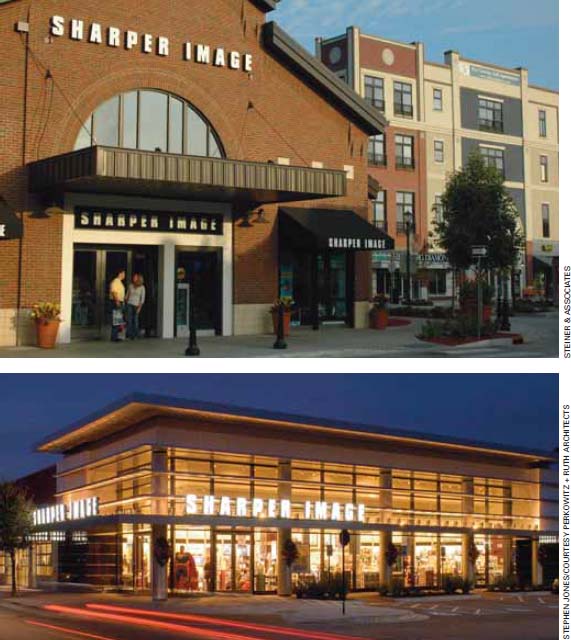

Even as design and leisure are more at a premium, creating strategies that showcase the stores and their products is crucial to attracting a good mix of tenants and giving them the visibility they need. The design of Zona Rosa, a new town center in the northern suburbs of Kansas City, Missouri, is based on a street grid with buildings close to the streets, open spaces, and walkability.

Moreover, Generation M associates shopping with activism. Bombarded at an early age by clamoring brands, these young people consequently look for some meaning in their environments. They respond to authenticity and are suspicious of corporate objectives. As a result, initiatives like Target’s pink pop-up stores for breast cancer and Nike’s Livestrong bracelets resonate with this generation.

Creating smart suburban downtowns with a mix of uses can help form the logical connections to workplaces, shopping venues, and transportation that help these new Americans get to jobs, access a variety of stores to meet their needs, and retrieve public and educational services. Sensitive retail development can create vibrant community hubs that provide social support networks to enable immigrants to thrive in their new country.

For retail developers, mixed uses provide an opportunity to capitalize on all these advantages, creating built-in customers. Mutually supportive uses may generate higher total revenue than the sum of their parts. When carefully selected, the uses benefit from people visiting them at different times for different reasons, potentially creating around-the-clock revenue. Developers daunted by front-end risk—or inexperienced in one of the individual uses—will find that, over time, mixed-use development is a more sustainable investment than, say, a strip mall or some other single-use development. Not only will they be helping to develop places that will mature over time; they also may be rewarded by a variety of financial and zoning allowances offered by many cities.

Initially a challenge, parking became an advantage to Bridgeport Village in Tualatin, a suburban community in the Portland, Oregon, metropolitan area. As regulated by urban growth boundaries, structured parking was required. The four-level parking structure for the 502,000-square-foot (46,655-square-meter) center provided seven to eight additional acres (2.8 to 3.2 hectares) for retail and open space. The 1,140-car structure is concealed behind the urban grid, which allows parking to be close to shops for customers’ convenience. Valet parking and surface parking are located strategically near restaurants, medium-format soft goods retailers, the supermarket, and convenience shops. The grid consists of eight 180- by 180-foot (on average) (55- by 55-meter) blocks.

Successful models already exist everywhere. Revitalized urban neighborhoods reveal that living above the shop really does work (as it always has) under the right conditions. New master-planned communities reveal that if cities, planners, developers, and designers work together from the start, the right density, pedestrian flow, scale, and tenant mix can make complex mixed-use development viable. Traditional shopping centers show that developers increasingly value links between public transit, offices, and residences that make shopping a more natural and convenient extension of people’s lives. Inside stores themselves, retailers are hoping to extend shoppers’ stays by embracing and communicating the “living” aspects of their brand.

From massive projects like Victory Park in Dallas and Atlantic Station in Atlanta to smaller projects like Highland Row in Memphis, Tennessee, mixed-use development is everywhere these days. But what defines mixed use? Is it a shopping center with 10,000 square feet (930 square meters) of office above retail? Is it a lifestyle center surrounded by power retail and apartments? Shopping Center Business (SCB) asked a number of expert developers across the country to share their opinions about what creates a mixed-use project and what parameters they use in deciding whether a project is mixed use.

We also wanted to know why everyone is developing mixed-use projects. Where is the demand coming from? Who is driving the industry to develop mixed-use properties? We have also seen a trend of mixed-use development in the suburbs, where strip centers and sprawl traditionally have ruled. Why are developers choosing suburban and rural areas to build mixed-use vertical projects?

A debate has surfaced in the industry about mixed-use projects versus multiuse projects. Some developers believe that many are inappropriately calling their projects mixed use. “I’ve heard ‘mixed use’ described as an apartment building with a dry cleaners and a café at the bottom,” says Brian Jones, CEO of Forest City Commercial Development’s Western Region. “And I’ve heard ‘mixed use’ refer to huge communities where you have housing and other uses. It is a misused name.”

Jones’s comment leads to the root of the debate: any project with more than one use can seemingly be termed mixed use. Along with the term “lifestyle center,” mixed use is the industry’s other ambiguous term.

“A true mixed-use application by our definition is multiple uses in the same building,” says Craig Kaser, president of TerreMark Partners, based in Atlanta. His thoughts are echoed by many developers, who believe that projects with many different property types in separate buildings should be termed “multiuse.” If that is the case, then a center with an adjacent hotel or apartment building should be multiuse, not mixed use, whether or not a single developer controls the land.

“‘Multiuse’ would be more horizontal in nature,” says Jones. “You have a number of uses in a planned project. As an example, I would describe our Victoria Gardens project, where we have a number of uses in one plan, as multiuse. Our Westminster project, where we have residential, lifestyle and power retail, and office space, is multiuse. It is a meaningful plan that incorporates all those uses. There are a lot of multiuse projects underway.”

Most of the developers SCB talked to agree. Overall, they also agreed that retail will create the draw but that residential and office space also must have a demand in the market to make the project viable. They also thought that mixed use should be vertical by nature and that each use must serve its purpose independently yet work together.

Some developers take the view that one exception seems to exist to the rule that mixed use must be vertical: if there are multiple uses in separate buildings, they must be located within a walkable environment. This definition would still exclude shopping centers with hotels or power centers on the periphery where the shopper is more likely to drive. It would include, however, communities where residents of an apartment building are likely to walk half a block to the retail component.

“In a walkable community, having uses in separate buildings does not break up the mix, as it were, but rather contributes to the overall diversity of the project,” says John Crossman, president of Florida-based Crossman & Company.

But the real difference, say others, is the way a project is developed. Is it being developed as a single project or as multiple projects developed on one piece of land?

“There is a very distinct difference between mixed use and multiuse,” says Clayton McCaffery, vice president of Chicago-based McCaffery Interests, developers of the award-winning mixed-use project, The Market Common, Clarendon, in Arlington, Virginia. “A mixed-use project requires the skill of the developer to thoughtfully and creatively work with investors, retailers, residents, and office occupants to understand and feel comfortable with the integration of each party’s interests and demands into a single cohesive project.”

Most developers SCB interviewed generally agreed with the definition that a mixed-use project must have three or more significant uses and physical integration that creates a single plan. Some developers narrow the number of uses to two when the project contains multifamily housing or office and retail. Most developers also agreed that retail is the must-have sector in a mixed-use development, with multifamily a close second, followed by hospitality, third, and office, fourth. Most developers did not have a hard formula of percentages that they allocated to each sector when developing mixed use.

“Percentages are more often dictated by local demand,” says Rodney Tucker, CEO of Citation Development, which is developing three mixed-use projects in the Las Vegas market. “Each component should act as a catalyst to support and enhance the complementing adjacent components.”

Retail is generally the most noticeable of the sectors in a mixed-use environment. It is what creates the project’s energy as well as the main attraction for outside visitors and what makes them feel a part of the project. Office, multifamily, and hotel uses must have significant demand to warrant their participation.

“For every use you introduce, the complexities of the development increase dramatically,” says Dougall McCorkle, vice president of commercial properties for The Lutgert Companies. “Often, each use has opposing needs. Office space and retailers both need convenient parking, for example, but parking for office space is static while retailers need those spaces to turn over quickly. Nonretail uses need ground-floor access and visibility, but it has to be done in a manner so as not to create dead zones in the retail landscape. And restaurants and residential units obviously have opposing needs when it comes to noise and energy.”

Many mixed-use projects are driven by developers whose history is in retail development, though most of the developers SCB interviewed have altered their practice to focus specifically on mixed-use properties. Some retail developers have brought in partners to develop other uses in a center.

“If you bring in codevelopers for certain uses of the project, then a whole new set of complications arise,” says McCorkle. “Factoring in the inevitable financing requirements from the lender with regard to preleasing office versus retail space and preselling condos really takes a lot of skill, patience, and perhaps luck to make the stars and moon align enough to pull it all off.”

Source: Excerpted and adapted from Randall Shearin, “Mastering Mixed-Use,” Shopping Center Business, June 2007, pp. 58–78. ©2007 France Publications, Inc.

All these tenets combine to create new models of retailing. No longer limited to regional malls and strip centers, today’s retail environment, while still resting on the tried and true rules of retail design, comes in all shapes and sizes.

What was old is now new again. The paradigm shift in retail development at the turn of the 21st century was the trend away from new enclosed and conditioned retail environments and an increasing focus on the development of open-air, street-oriented places for even the largest centers. The rise of an overall urban planning movement known as the new urbanism is at the heart of that shift. Based in part on the tenets of early 20th-century town planning and the still dominant European high street, these places feature a central commercial core with the highest density, then decreasing density of commercial and residential uses surrounding it.

This return to the basic urban design strategy of knitting uses together through the layout of streets and blocks has called into question many of the design norms of all types of shopping centers. A desire to shift importance to walkable streets and away from acres of free parking has transformed not only the design of new retail environments but also the renovation and expansion of existing ones. Street-oriented developments are gaining ground, and enclosed malls are being reinvented by adding open pedestrian components and incorporating other uses on former surface parking lots. Street-oriented developments, whether new or adaptive, are widely seen as having a more positive long-term benefit to their communities.

What was once a strict divide between enclosed and open-air shopping environments has begun to close. For ground-up developments, the term “open-air” once denoted single-loaded lines of stores facing parking fields that were usually targeted to lower- to mid-market shopping such as grocery-anchored and power centers. More extensive mid- to high-end comparison shopping in newly developed projects was associated with enclosed malls. Today, in places like Bowie Town Center in Bowie, Maryland, and The Grove in Los Angeles, “open-air” connotes new associations with traditional downtown street settings and represents all levels of shopping and price points. More important, though, these types of developments have ushered in the current phrase “lifestyle center.”

Does Your Life Have Style? As with most trends, clearly and specifically defining what a lifestyle center is poses a few complications. The phrase has become overused and vague, and what began as a leasing strategy has given rise to a wildly diverse project type that seems to have only a few common attributes. Yet everyone seems to know one when they see one.

Poag & McEwen, a Memphis-based developer, is largely credited with coining the term, but even its portfolio is diverse enough to question just what a lifestyle center is today. The International Council of Shopping Centers, sensing confusion among the ranks, tried to lay down the law and offered the following definition:1

A lifestyle center is most often located near affluent residential neighborhoods, has an upscale orientation, contains 150,000 to 500,000 square feet (14,000 to 46,500 square meters) of GLA, is built in an open-air format, and includes at least 50,000 square feet (4,650 square meters) of national specialty chain stores.

So that settled the matter. Or did it?

Increasingly, no one definition exists: shopping centers continue to hybridize and evolve, mixing components as market, location, and consumer preferences dictate.

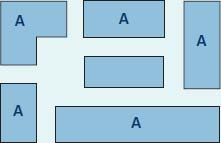

From the standpoint of leasing or merchandise mix, lifestyle tenants tend to be those specialty retailers whose product line is focused on a particular ethos or activity. Barnes & Noble, for example, is often considered a lifestyle anchor because it responds to a culture that allegedly values all things literary. Nevertheless, the need to expand the notion of convenience and to serve the value-conscious consumer has led to the inclusion of big-box stores in such centers.

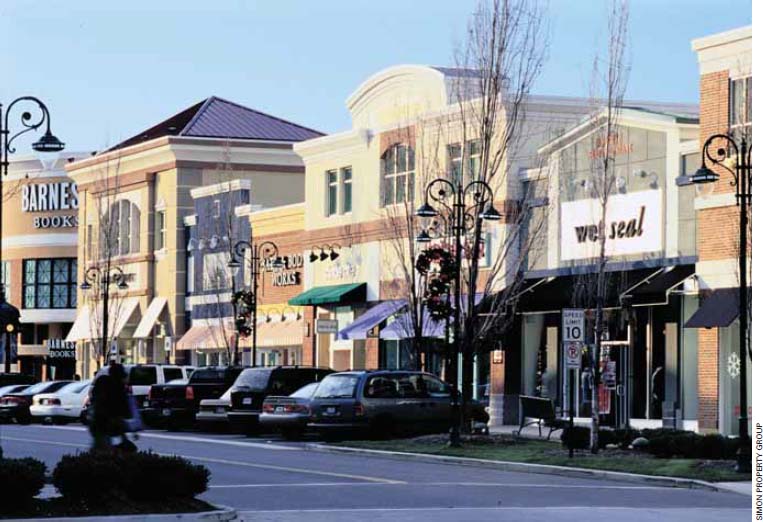

Four architecture firms designed an eclectic mix of buildings at Victoria Gardens in Rancho Cucamonga, California. Each street has a different feel: buildings evoking craftsman, mission, and Spanish colonial styles are located along North Main Street; South Street, where the department stores are located, evokes streamlined modernist styles; and the town square is surrounded by civic-looking structures that mimic the neoclassical style.

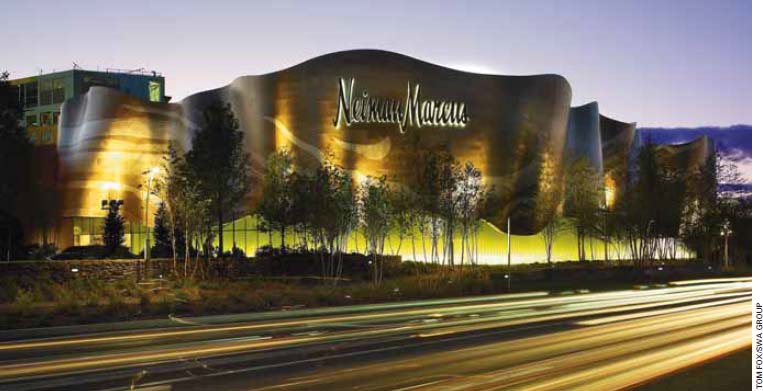

The iconic exterior facade of Neiman Marcus is part of the new expansion at Natick Collection in Natick, Massachusetts. The new addition also features condominiums above the mall shops with direct elevator access to the mall.

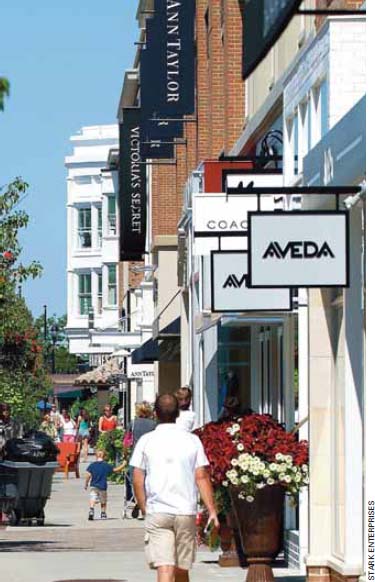

Moreover, from the perspective of design, lifestyle centers tend to be hard to pin down. Some are heavily themed environments that try to replicate well-imagined streetscapes such as The Grove (profiled in Chapter 9), while others favor a more authentic approach and try to tap into a local design vernacular or aesthetic such as Crocker Park. Either way, these centers do seem to rely on open-air environments, mix food uses with retail uses, and emphasize the social aspects of shopping. If a mall encourages circulation, the new format encourages shoppers to sit and relax. Thus, more attention tends to be paid to the details of the environment, especially those things that come in direct contact with the shopper such as tiling and paving, landscaping, and storefront details.

Beyond the Strip-Center Mentality. Conventional open-air centers have also evolved dramatically. What used to be considered a strip style of development has lost its luster, and today’s high-quality developments include many amenities and open spaces, with sidewalks, streets, and plazas treated as a series of outdoor rooms. Spaces between buildings are as carefully choreographed and composed as the buildings themselves. The artful arrangement of furnishings, lighting, fountains, special paving, and performance areas is key to capturing the most positive attributes of the traditional shopping street.

The success of these new developments, many of them patterned after established, long-successful urban shopping districts like Country Club Plaza in Kansas City, Missouri, results in a focus for planning, design, and development known as “Main Street.” These developments are influenced by traditional town planning concepts, melded with many of the merchandising and anchoring concepts of regional malls such as Victoria Gardens in Rancho Cucamonga, California.

The Right Flow. The single-loaded strip center has been relegated to those sites where the automobile still reigns and municipal agencies are less concerned about sprawl or single-use developments. The more successful model lines a street environment with buildings on both sides and provides generous sidewalks and head-in, angled, or parallel parking. Two-level centers, with second-level retailers reached directly only from the second level, are rarely successful, but some examples do exist. Two-level retailers or restaurants reached from the ground floor are more likely to succeed. Adding residential units to the development not only increases security by adding a self-policing environment but also helps activate the environment at several times during the day.

Although pedestrian-only open-air retail environments are common and often successful, most developers opt to create vehicular streets with sidewalks. This solution provides the opportunity for on-street parking that, although limited, is important in the minds of both retailers and shoppers. Vehicular streets also capture more successfully the ambience and bustle of traditional street shopping. The coexistence of cars and pedestrians is encouraged and managed through carefully controlled street and sidewalk widths, appropriately placed crossing points, and on-street parking. Additional traffic mitigation is handled with traffic calming devices such as table intersections.

Fitting the Pieces Together. Once traffic issues have been resolved, attention should be paid to the interaction of streets, sidewalks, and setbacks. Streets and sidewalks of a certain width provide optimal dimensions for generous sidewalks, on-street parking, and two-way traffic. A building-to-building dimension of 80 to 86 feet (24 to 26 meters) provides for a 15-foot (4.6-meter) sidewalk, an optimal width to allow for projection of building awnings and signage, street trees, limited outdoor dining, and curb overhang of vehicles. It also provides for approximately 30 to 32 feet (9 to 9.7 meters) for angled head-in parking and 20 to 24 feet (6 to 7.3 meters) for two-way traffic.

Alternatives to curbs can achieve comparable (in some cases, enhanced) interaction between streets and sidewalks. For example, bollards (rigid posts that serve as a symbolic and actual barrier to vehicles) with no curbs delineate streets with easier transition for pedestrians. Still, this approach is not without challenges as raised planters on sidewalks can become barriers to pedestrians, thereby reducing the overall impact and familiarity of the classic shopping street experience.

Climate Concerns. Although an open-air center might seemingly be more successful in a warm climate, many examples exist of success even in colder, wetter areas, and attempts at total protection from rain are typically unwarranted. Tenant- or landlord-provided awnings and overhangs allow shoppers to duck out of the rain in case of a downpour.

With a resurgent interest in downtown and city shopping, an increasing number of infill developments are being created. Layered with many more complexities than suburban development and often working in the context of an unusually shaped site, urban infill development poses the need for complex design. That said, urban infill development can provide easy-to-understand demographics, an existing infrastructure, an instantly recognizable address, and smaller, more manageable development sites.

Going Up. In the densest urban areas, verticality makes financial sense. As open urban spaces diminish, the shortage of real estate drives development expenses up. Because of the difficulties in assembling land for retailing, vertical retail, the layering of multi-tenant retail space in a compact city block, is a challenging but viable option and can enhance a pedestrian-friendly environment.

Century Theatres created a prototype with two separate theaters under one roof for Church Street Plaza, a $181 million mixed-use redevelopment project in downtown Evanston, Illinois. Both the city and Northwestern University owned the 7.2-acre (2.9-hectare) site; the intent was to create a vibrant place for faculty and students to enjoy. CineArts has six screens showing independent and specialty films geared toward the university audience and a traditional multiplex with 12 screens. The two theaters, each with its own lobby, are on the second floor to maximize retail space at the street level.

The challenge of vertical retailing is to encourage shoppers to move upward, beyond just the one or two levels they would normally visit. The same analysis of anchoring that typically happens horizontally in a suburban project is attempted vertically, requiring an equal draw to be placed at the top and pedestrian traffic pulled farther into the diagram. Common areas are lined with stores like a mall, with floor openings to visually connect the levels.

It is most common in highly dense urban environments such as in Asia’s major cities, where multiple examples of vertical retail exist and thrive. Density of people is a critical aspect in making vertical retailing succeed. Namba Parks, an eight-story shopping center in Osaka, Japan, is profiled in Chapter 9.

Although density in North American cities generally is not sufficient to support such verticality (and it has not been the preferred experience among shoppers), this configuration has been successfully developed in certain cities. For example, Westfield San Francisco Centre opened in 2006 when an existing vertical center was expanded to include the renovation and reconfiguration of an adjacent historic department store. The two structures that make up the Westfield San Francisco Centre are linked on five levels, with a Nordstrom store positioned at its upper floors as one of the anchors.

Parking Challenges. Generally speaking, city ordinances require more parking space than needed, as they are more likely based on a single-use suburban model without adjusting for shared parking or pedestrian (residents, office workers, tourists) and transit access. A few exceptions such as Manhattan, Boston, and San Francisco exist, where ordinances in effect allow developers to provide the number of spaces the developer determines is sufficient.

Regardless of the process used to determine the number of spaces, costs associated with underground parking must be considered; such costs are one of many financial impacts that force developers to rely on market conditions that allow for substantial rents and assume pent-up demand in the marketplace.

Navigation. From a functional standpoint, the most important design consideration in urban infill retail development, as in any retail development, is to craft a pedestrian flow that propels shoppers through the entire space. In vertical configurations, the positioning of escalators, elevators, major tenants, access points from the street, and parking is of paramount importance and is very different from that required for horizontal or suburban counterparts. Infrastructure design is also a challenge, as vertically oriented spaces for service and deliveries, HVAC, and life-safety systems affect cost and structure.

Beyond function, the design statement created—that is, the story told by the project and the sum total of the visitor’s experience—is equally important. A high-quality experience borne out by materials, details, and ambience is the constant that puts a few urban infill retail projects in the top tier of retail development.

As successful models continue to pop up all over the United States and abroad, mixed-use development is finally being seen as a valid long-term investment for many developers. With a greater understanding of the front-end risks and how to accommodate them, developers are seeing how effective partnerships can lead to vibrant places that enjoy around-the-clock activity. With mixed uses, developers have the chance not only to get a longer return on their investment and at times benefit from public sector incentives or partnerships but also to introduce uses that strengthen the rest of them.

Integrating Office Space. Increasingly, office uses are positioned directly above retail space in open-air settings. This blending of uses has multiple benefits. Where offices occupy second and third stories only, tenants tend to be small, professional, medical, legal, or real estate businesses and provide a moderate daily traffic flow for the retail space tenants, particularly restaurants. Higher-rise office space often attracts larger companies but, in any case, the total additional employees provide stronger support for the ground-floor retail space. Companies that offer retail and/or residential space in addition to office space provide an additional benefit to employees and create a better workplace. Places like Legacy Town Center in Plano, Texas, and Kierland Commons in Scottsdale, Arizona, have successfully integrated office with retail space.

At least some on-street parking is important in these projects because of the perception of convenience that it provides. Actual parking requirements are typically filled through a combination of on-street parking and fields of parking located behind the buildings, with amenity-rich passages connecting them to the retail main street. Although parking structures provide more parking closer to the street, the economics of most open-air centers make garage construction financially difficult. In some cases, cities motivated by the promise of additional revenue from sales taxes and the creation of a dense commercial core fund structured parking and other infrastructure through public/private partnerships.

Structured parking and vertical mixed uses at Crocker Park in Westlake, Ohio, resulted in a project with 26 percent open space that includes median parks, neighborhood greens, and sidewalk places. The site was a 75-acre (30-hectare) greenfield; Crocker Park now incorporates more than 600,000 square feet (55,760 square meters) of retail space with more than 1 million square feet (93,000 square meters) of upper-story apartments and office space, townhouses, and condominiums.

Residential units are located directly above ground-level retail at Santana Row in San Jose, California. Now a high-density, multistory mixed-use neighborhood, the project replaced a 1960s-era single-story suburban shopping center.

Integrating Residential Space. Residential uses above or adjacent to open-air retail increasingly are seen as adding value to a retail-driven development. Chances of the development’s long-term sustainability increase, based in part on the built-in customer base for shopping and on opportunity for multiple revenue streams. This form of mixed-use development is designed horizontally (often called multiuse), with residential blocks adjacent and connected to shopping streets (as in Legacy Town Center) or vertically (called mixed use), with residential uses directly above the stores (as in Santana Row in San Jose, California, and the Market Common, Clarendon, in Arlington, Virginia). Vertical mixing is generally regarded as more challenging from the points of view of both development and design. Mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems of the residential portion must be clustered to minimize the impact to the retail leased space below, and the ideal column spacing for the uses tends to complicate the situation. Office above retail, as noted, typically has much less impact on stores below. Additionally, horizontally organized retail/residential master plans can be implemented more easily through multiple developers.

Residential mixed with retail has another very practical added benefit. The perception of security is increased, simply because in the evening and later (when stores close) spaces are occupied above or near the shopping streets, resulting in more eyes on the street: in effect, residents become watchdogs for the development. Thus, opportunities for trouble are minimized compared with a dark, single-use street.

The proliferation of mass transit in major U.S. cities has spawned a new form of retail-driven development around the stations serving these systems. New stations often create value where it did not exist before (Mockingbird Station in Dallas, Texas, for example). Delivering more customers at more hours of the day, transit has become another form of “anchor” for retail developments. The blending of residential and office space further capitalizes on the connectivity to other areas of a city through mass transit, and cities typically encourage mixed-use development near transit stations, allowing greater density at these locations.

Downtown Silver Spring in Silver Spring, Maryland, is an infill project by The Peterson Companies developed near an already established transit district.

One obvious benefit of transit-oriented development is the promise of diminished reliance on automobiles, a notion that may translate into less need for parking. Although parking mitigation is a clear asset and encouraging the use of mass transit is consonant with smart growth initiatives, exactly quantifying these benefits can be difficult. The actual walking time from the transit station to the retail center, for example, may be beyond what most people consider convenient, and the willingness to use transit for shopping trips varies depending on local norms and density. Nonetheless, transit-oriented development will become increasingly important in the real estate industry, especially in those regions where population growth is most pronounced.

Given the public’s interest in open-air formats, developers, and especially REITs, continue to explore the evolution of the traditional model and how to maximize the value of an asset. Hybrid malls—those that mix indoor and outdoor spaces or traditional retailing with lifestyle or entertainment-driven tenants—have become an increasingly popular new type of development.

At Market Street at The Woodlands near Houston, Texas, the spaces between buildings were designed to act as outdoor rooms, encouraging shoppers to linger and relax.

Englewood City Center. The first major transit-oriented development (TOD) in the Denver area, Englewood City Center receives frequent visits from practitioners seeking to understand the concept of TOD. Encompassing 55 acres (22.3 hectares), Englewood City Center is a public/private development that was completed in 2002 to replace an aging shopping center. It includes 438 residential units, 700,000 square feet (65,100 square meters) of retail space that includes a Wal-Mart, the Englewood municipal offices and library, and a large civic open space.

Englewood City Center offers numerous lessons for how to develop TODs. The site is well laid out and walkable, particularly from the station platform. Residential development (whose residents are most likely to use light rail), the civic center, and the park are located closest to the station. Most major retailers are visible from the nearby major roadway, and all uses are connected on a street grid, with pedestrian connections to adjacent neighborhoods.

Public art abounds. In addition to a fountain in the park, numerous pieces of public art, mostly sculpture, improve the pedestrian realm.

Much of the development is denser than the surrounding area, and mixed-use buildings are common. For example, a gym is located on the second floor of a retail structure. Many of the residential buildings contain ground-floor retail space, and some retail structures include second-story office space.

A critical piece of Englewood City Center, Wal-Mart provided the financing for the project to move ahead. The city and developer realized that a big-box store and light rail could both be part of the same project, as long as they were in appropriate locations on the site. The Wal-Mart site is also part of the street grid, enabling it to be more easily redeveloped in the event the store closes.

Developers: City of Englewood, Miller Weingarten, Regional Transportation District, Trammell Crow Residential, Wal-Mart

Area plan: Calthorpe Associates

Brighton Pavilions. Adjacent to an existing bus park-and-ride in the northeast Denver metropolitan area, Brighton Pavilions opened in 2005. Designed by Gensler, a Houston-based architecture firm, it includes retail space, restaurants, and a 12-screen movie theater on a 14-acre (5.7-hectare) site near downtown Brighton.

Brighton Pavilions is unusual in that it is a TOD based on bus, not rail, service. It is, however, a successful partnership with the Regional Transportation District. The retail stores and park-and-ride service are complementary uses, and each benefits from the other, particularly at commuting times. Commuters share the parking facility by day, patrons of the theater and sit-down restaurants in the evenings.

Developers: Brighton Urban Development Company, city of Brighton, Regional Transportation District

Source: Adapted from Sam Newberg, “ULX Ten Denver TODs,” Urban Land, September 2006, pp. 76–80.

Although the hybrid is an evolving model, a number of consistent elements are starting to emerge. Successful hybrids rely on seamless transitions between spaces as well as aggressive leasing strategies to ensure a consistent and appropriate tenant mix. As one might expect, hybrids combine the complications of their respective components—parking, circulation, sight lines, anchoring, tenanting—but offer shoppers greater diversity in environments and typically bring developers greater flexibility in leasing.

Unquestionably, the United States led the world in mall development for more than four decades following World War II. Driven by ample space, a growing population with immense buying power, and affordable gas prices, the United States built shopping centers in middle-class suburbs and anchored them with large department stores in simple horizontal structures surrounded by a sea of cars. Internationally, however, retailing remained more localized and much more compact, owing to historic urban development or sheer population density and greater reliance on foot traffic and public transportation. As conditions in the United States urban market change—less space to develop, rising land costs, high gas prices, and a shift in consumers’ preferences—the United States is starting to look to international models for ways to adapt the shopping environment.

Discussions about shopping centers all over the globe share some commonalities. Successful retailing everywhere contains several fundamental elements: demographic relevance, attractive anchors, effective circulation, good sight lines, and an appreciation for the shopping experience. But increasingly, developers in the United States are learning several lessons from overseas models.

The 300,000-square-foot (28,000-square-meter) Ayala Center Greenbelt 3 in Manila integrates outdoor space with retail. A series of highly landscaped courtyards, plazas, and walkways line one side of the development; on the other side, retail is oriented toward city streets.

Before the emergence of lifestyle-oriented and mixed-use centers, the American enclosed regional mall provided the standard for many parts of the world. Today, the opposite is occurring. International retail models are increasingly being applied to American centers.

Asia’s dense population has necessitated vertical design. In Japan and Taiwan, shopping centers can tower as high as 12 stories. China has borrowed from both other Asian and global models, maintaining a vertical structure while extending horizontally where possible. Divided into distinctive halves, City Crossing in Shenzhen, China, for example, is a moderate four and six stories high. Chinese shopping centers are largely enclosed structures, allowing patrons to escape the hot, damp summer climate.

Department stores in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea have a different character and merchandising strategy from their U.S. counterparts, which often works against the success of inline shops. Most Asian department stores lease space to certain international brands such as Burberry and Gucci, making them a type of shopping center within a shopping center.

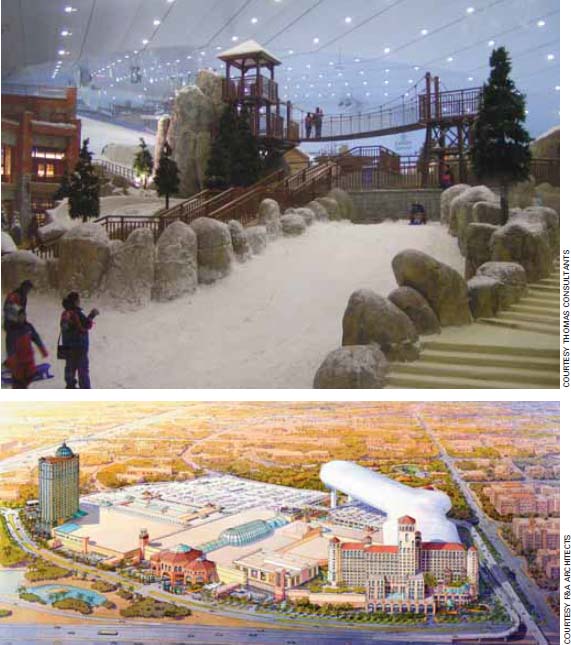

American-style retail development in the Middle East has existed for many years, and it continues to evolve. Cultural, economic, and climatic issues pose a wealth of challenges to architects, developers, and retailers interested in the market. Yet despite these challenges, many Arab countries have embraced an aggressive commercial approach to development and have creatively adapted Western-style retail models to fit their indigenous cultures. The United Arab Emirates has been among the most progressive countries in the region in translating western shopping trends into a local context, while even the more conservative Islamic cultures have figured out ways of adhering to sharia law and maintaining a robust retail environment. In Saudi Arabia, for example, where women are required to be veiled in public, retail designers have created special anchors where women can enter, unveil, and, in the presence of women only, enjoy a pleasant shopping experience. The hot desert climate limits the use of skylights and water, two fundamentals in many western-style developments. But Arab architects have been dealing with these issues for centuries, creating public markets (souks) that have vitality and a sense of place that rivals anything the West has to offer.

Many Arab countries have embraced an aggressive commercial approach to development and creatively adapted western-style retail models to their local context. Mall of the Emirates in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, has 2.4 million square feet (223,000 square meters) of GLA and includes an indoor ski slope.

Although many Asian malls have successfully translated the familiar formula from the United States — large anchor tenants, powerful branding, a coordinated merchandising mix, and comfortable, climate-controlled surroundings—fundamental differences in composition remain. Malls in Asia tend to have many more stores, which tend to be much more compact, with a shallow footprint. This phenomenon stems from many factors but ultimately arises from a cultural tradition that revolves around the local bazaar or outdoor market as the community centerpiece.

The second phase of Pondok Indah, a three-level mall in Jakarta, Indonesia, is an example of an American mall translated into an Indonesian setting. The transfer of American retail technology and planning to Indonesia, in combination with recognizable elements of Indonesian art, society, and retail culture, resulted in a distinctive finished product. Completed in 2005, the 614,000 square feet (57,000 square meters) includes retail and entertainment space.

These markets, or souks, represent some of the earliest and most organic “malls.” The densely packed clustering of small individual stalls and the resultant commercial intensity represent retail exchange and social interaction at their most essential. The design of Pondok Indah, in Jakarta, Indonesia, may break rules in a nation accustomed to small shops crammed into a retail space with limited public amenities, but it still manages to capture the bustling vitality and communal energy so familiar to local residents. Pondok addresses the issue of more stores and smaller parcels by devoting more open space to the movement of pedestrians. Broad avenues and frequent literal and metaphorical connectors facilitate intuitive, free-flowing circulation.

Pondok Indah is clearly a contemporary space, but the fusion of its contemporary elements with the vitality and subliminal geometry of a traditional souk has transformed it into a place that transcends traditional formulas and creates something entirely new.

Acknowledging these cultural touchstones through design can have significant benefits. Just as mall design in the United States has recognized that a connection exists between enlivened, activated spaces and profitable places, the design of Asian malls is undergoing a similar philosophical renaissance. The energy and creativity behind that renaissance have fueled a corresponding flow of inspiration to the United States and Europe.

In particular, by embracing the concept of integrated entertainment components to a greater extent than is done in the United States, Asian malls like Tai Mall in Taipei, Taiwan, and Bandung SuperMal in Bandung, Indonesia, have shown that heretofore unheard-of levels of interactive entertainment can not only work in a retail environment but also thrive there. The entertainment component of Pondok Indah’s second phase includes an ice rink, a bowling center, state-of-the-art technologies employed in three-dimensional interactive games and rides, and even a climbing wall—an array of entertainment options rarely found in the United States.

Preexisting civic infrastructure often dictates design decisions, and the fundamental question of where — and how—a project will fit into the urban landscape is frequently a more pressing and complicated concern in Asia than it is in the United States. Global retailers like IKEA and Wal-Mart illustrate the dichotomy perfectly. In the United States, these companies are uncompromising in their dedication to freestanding pad locations with a warehouse-style floor plan. But in Asia, IKEA and Wal-Mart are frequently located inside a larger mall with a vertical, multilevel layout. Second-level entries are not uncommon, with no ground-level access whatsoever.

Pondok Indah’s design aesthetic exhibits an unmistakable Asian influence, with open courts and soaring, elegant spaces throughout.

In Asia, where despite a recent boom in suburbanization the vast majority of people live in densely populated urban areas, malls must not only become part of the urban landscape but also bring some of the energy and dynamism of that urban environment inside. In the retail context of metropolises like Tokyo, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Mumbai, dramatic lighting, powerful graphics and signs, and an energized retail environment are necessary commodities.

The story of Asian malls is as much about limits as it is about possibilities — as much about which ideas to exclude as about which to include. The marketplace of ideas flows freely across geopolitical borders, but an intellectual flexibility and a willingness to make allowances for culture and setting can make the difference between a resounding success and a dull thud.

Although the genesis and subsequent evolution of the modern mall is a distinctly American phenomenon, it would be an oversimplification to say that the United States “exported” malls and contemporary retail concepts to Asia. The reality is much more nuanced, involves a much more reciprocal relationship, and is much, much more interesting.

It boils down to the fact that the place dictates the design and function of a retail environment. Understanding and appreciating what makes a successful mall requires, on a fundamental level, mastery of the same information in Asia as it does in the United States. The data might be different, but the analytical tools and design and development prerequisites are identical: know your people and know your place. A well-designed retail space comforts, satisfies, and stimulates people while honoring the spatial relationships, cultural priorities, and aesthetic synergies of the place.

Like Pondok Indah and its contemporaries, once fundamental cultural distinctions have been taken into account, it is then possible to innovate, adding elements that expand boundaries and challenge conventional notions about design and development. The journey from cultural context to a built environment is not a long one, and the ultimate destination is well worth the trip.

Source: Excerpted and adapted from Ahsin Rasheed, “The Great Mall of China,” Urban Land, January 2007, p. 82.

An urban infill project, Potsdamer Platz Arkaden in Berlin, Germany, includes more than 430,000 square feet (40,000 square meters) of retail space and seamlessly blends shopping with the public realm.

Since the late 1970s, Europe has drawn on U.S.-style retail development to both positive and negative effects. Many of the out-of-town developments that sprang up in the 1970s and 1980s duplicated the mistakes of U.S. centers from the previous decade: reliance on automobiles, single-use centers, and acres of surface parking. Culturally, some facets simply did not translate. Food courts, for instance, perfect for an American shopper concerned with convenience and speed over quality, were out of sync with European sensibilities. Beyond these differences, complicated lease and ownership structures often meant that the centers were difficult to renovate, leaving huge retail behemoths hulking on the edge of towns.

To combat this outcome and to encourage their urban locales to regenerate, many European countries enacted legislation sharply restricting out-of-town development. The result has been a greater emphasis on urban or intown development. Although these projects do not have the density of Asian retail centers, they tend to be multiuse and multilevel. Retail and residential uses are almost always combined, and public transportation plays an integral role in generating the necessary foot traffic. Park Place in Croydon, England, mirrors this development style by offering a retail and office district connected to a bus station.

European retailing has long been defined by town centers that blend shops, residences, and civic uses within clearly defined borders and edges. Because they provide successful examples of navigation and prove to the rest of the world that living above a shop is a viable format, the international development community has looked to these European town centers as models for smart growth. At the same time, European retail developers have looked to international urban retail projects to meet the challenges of the dwindling number of greenfield sites and increasing pressure to build sustainable developments.

As in other parts of the world, retailing in Central and South America reflects cultural and economic forces. Large suburban U.S.-style centers are the exception, though several exist, especially outside larger cities. As in Europe, such centers tend to mix fashion retailing with durable goods and convenience shopping, so it is not uncommon to find a grocery store or hypermarket in a mall environment. Different from most global models, Latin American anchors are often a combination of large-format (medium by U.S. standards) retail, restaurants, and common space. Because the region’s retail formats are smaller, circulation is more flexible, and navigation and public space planning can be more innovative. Perhaps because of the tangible and dynamic nature of Latin American culture and the inviting climate, developers are often more open to cutting-edge design than their counterparts abroad. One significant difference between U.S. and Central and Latin American centers, particularly for higher-end examples, is the presence of security guards and equipment.

Planning and design can move beyond the preliminary or conceptual stage once the feasibility of creating a shopping center has been determined. Designing a shopping center is more complex than ever given changes in consumers’ preferences, evolution of the retail model, and increase in uses and functions.

One issue that spans both site and building planning is the need to design for people with disabilities. Under provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), today’s centers must be accessible to the handicapped. ADA covers arrival and parking areas, walkways, ramps, entrances and doorways, corridors, stairs, elevators, toilet facilities, drinking fountains, public telephones, and signs. Federal, state, and local laws mandating accessibility in privately owned public buildings (including shopping centers) are incorporated into building codes. The developer and the design team must be aware of all accessibility codes and must make certain that the requirements are incorporated in the center’s design. Failure to do so will add costs later, because installed features that fail to provide access to people with disabilities according to codes will have to be replaced with components that do. Such changes also take time and could delay the occupancy permit for the center.

Access and visibility are the most important factors in the successful design of a center. A clearly visible retail identity is essential to initiate and encourage pleasant arrival. A logical hierarchy of roads is crucial in leading shoppers safely and efficiently from the road network to parking for the stores. Locating entry and egress to the site for customers’ easy use is paramount. Once on site, providing ample and convenient parking allows the maximum number of customers to use the center without long walking distances.

With proper initial site planning, the functional aspects of the center will assuredly work for the life of the project. Proper site planning allows expansion of the initial project as economics permit. An initial site plan should take into account present program requirements (as outlined through a feasibility study) and the possible future requirements of the site, building in flexibility not only for growth and expansion but also for changes in use. Such changes may involve, for example, consideration of a one-level center that could one day accommodate an upper level and the requisite infrastructure entailed. Similarly, changes in anchors and food and entertainment strategies are inevitable, so the initial design must be inherently flexible.

Two of the most critical elements in designing for now and the future are the related issues of traffic circulation and structured parking. Preparing for logical design and construction that both support initial development and do not ultimately require the reworking of existing infrastructure (roads, utilities, and parking decks) is absolutely essential. Increasingly, phased development includes placing parking structures on the original surface parking sites to accommodate new major anchors and additional stores, all of which could not occur without appropriate initial planning.

Although it seems self-evident, it bears repeating that the parking lot is often a shopper’s first contact with a mall, and the experience of parking should be as pleasant and welcoming as possible. Too often, it is not. If visitors feel lost and disoriented—or worse, threatened—they will likely not return. Indeed, the parking area should support the center’s prime role of providing an attractive and convenient marketplace. Given the critical support function, as well as the significant land area devoted to it, parking areas must be carefully planned and designed. Components of parking design— size of parking area, driveway layout, access aisles, individual stall dimensions and arrangements, pedestrian movements from the parking area to the center, grading, paving, landscaping, and lighting—are major elements of site planning.

Kierland Commons in Scottsdale, Arizona, uses a hierarchy of streets to create optimal access to the site, directing traffic to the parking areas and facilitating movement in the development.

The guiding principles in planning the parking area are the number of spaces needed as well as required by the local zoning ordinance, and their best arrangement. Parking that is well distributed helps minimize the need for consumers to park more than one time per visit. A successful shopping center depends on adequate parking—not too much but not too little. For this reason, parking requirements at shopping centers have received considerable attention over the years.

Parking Standards and Demand. The fact that a customer usually visits several stores during a single shopping trip and the rate of turnover of the spaces distinguish parking requirements for shopping centers from those of freestanding commercial enterprises.

Parking standards are expressed as a parking ratio— the number of parking spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) of GLA in a shopping center. GLA is a known and realistic factor for measuring the adequacy of parking provisions in relation to retail use.

Based on a comprehensive study of parking requirements for shopping centers conducted by ULI and the International Council of Shopping Centers in 1999, the following base parking standards are recommended for a typical shopping center today:

Studies have established the 20th-highest demand hour of the year as the appropriate hour for determining requirements. The above standards will serve patrons’ and employees’ needs at the 20th-busiest hour of the year, allowing a surplus of parking during all but 19 hours of the more than 3,000 hours during which a typical center is open annually. In other words, during only 19 hours of each year, typically distributed over ten peak shopping days, some patrons will not be able to find vacant spaces when they first enter the center.3

In addition to size of the center, the amount of parking needed at a shopping center is affected by the treatment of employee parking during shopping peaks, the percentage of nonauto travel to the center, and the proportion of restaurant, cinema, and entertainment land uses.

The study found that approximately 20 percent of the total parking demand during the peak period is generally attributable to employees and incorporates this finding in the above ratio. Thus, centers that require employees to park off site during the peak season could see up to 20 percent reduction in parking demand. This adjustment should be used with caution, however, as centers with uncontrolled free parking often have difficulty completely enforcing employee parking.4

Although pedestrian-only open-air retail environments are common and often successful, most developers opt to create vehicular streets with sidewalks. This solution provides the opportunity for on-street parking that, although limited, is important in the minds of both retailers and shoppers. Vehicular streets also capture more successfully the ambience and bustle of traditional shopping streets. Pictured: The Greene, Beavercreek, Ohio.

Parking ratios apply to centers that are primarily dependent on autos, with minimal walk-in or transit use. Centers that are almost exclusively dependent on transit or pedestrian traffic must determine, through either existing zoning ordinances that may use reduced parking requirements as an incentive to build at transit stations or negotiations with the local government, what is required. Atlantic Terminal in highly transit-dependent Brooklyn, New York, sits on top of the third-largest transit hub in New York City and even with Target as the anchor, does not provide parking on site (see the case study in Chapter 9). Still, proximity to transit stations does not automatically reduce retail parking needs by a predetermined amount, as the location of transit stations may still require walking beyond the distance considered convenient. A favorable planning environment in the general area and appropriate site planning may encourage the use of transit in these situations.

Round bollards instead of curbs at Crossings at Corona, in Corona, California, are used to delineate walkways from roads, providing an easy transition for pedestrians. The size, shape, and spacing of the bollards clearly separate the two activities without interfering with sight lines and pedestrian flow.

The parking ratios presented above apply to centers that have no more than 10 percent of their GLA occupied by restaurants, entertainment venues, and/or cinema space. For centers where these uses occupy 11 to 20 percent of GLA, a linear incremental increase of .03 space per 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) for each percent above 10 percent is recommended. For centers where these uses occupy more than 20 percent of GLA, a different approach is recommended. Restaurants and nightclubs have significantly higher parking needs per 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) of GLA, and requirements for movie theaters are best calculated per seat. Further, these uses may have different needs for weekdays versus weekends, time of day, and seasonal requirements than other tenants in shopping centers. For this reason, it is recommended that determination of parking requirements where these uses occupy more than 20 percent of the center’s GLA be made through a shared parking analysis.5 The shared parking methodology provides a systematic way to adjust parking ratios for each of these uses.6

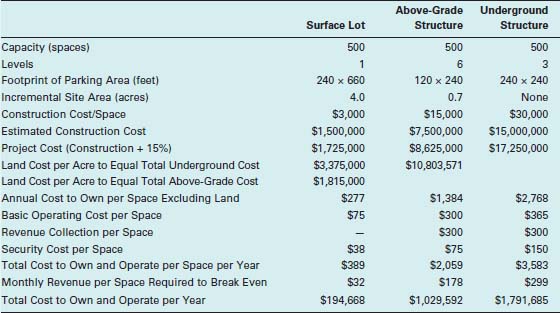

Shared Parking. Shared parking is the use of a parking space to serve two or more individual land uses without conflict or encroachment.7 The need to understand and adopt shared parking has grown as shopping center projects incorporate various nonretail uses on the same site, whether horizontally or vertically. Moreover, with parking costs ranging from $3,000 per space on grade to $15,000 per space in elevated structures to $30,000 per space for underground parking,8 the ability to reduce and share the total number of parking spaces becomes a valuable exercise for the owner to consider. Both developers and communities are demanding greater care in the design of parking areas to enhance the project.

Program uses that work best synergistically are those where patrons’ use peaks at different times of the day. For example, hour-by-hour use patterns detailed in Shared Parking for a wide range of retail and nonretail uses indicate that weekday parking for most retail peaks by midday and stays fairly constant until about 7:00 p.m., while parking for fine and casual dining peaks between 6:00 and 10:00 p.m., and that for cinemas peaks between 7:00 and 10:00 p.m. Office parking peaks during the work day, and use declines rapidly after 5:00 p.m.9

Different land uses experience peak parking demands at different hours of the day as well as days of the week and seasons of the year. In addition, the “captive market effect” of a mixed-use project influences parking demand; that is, in a mixed-use project, customers may be attracted to two or more land uses on a single auto trip to the project. Because of these characteristics, less demand is generated for parking space in mixed-use projects than in separate freestanding developments of similar size and character; moreover, two or more land uses may share a parking facility. For this reason, estimated parking demand for a shopping center that is part of a mixed-use development should be based on an estimate of shared parking demand for the entire project.

The methodology in the ULI/ICSC study of shared parking includes nine steps that can be used to estimate the parking demand in a mixed-use development:10

Structured parking rises above a grocery store at 40th @ Walnut near the University of Pennsylvania in west Philadelphia. University employees use the garage during the day, while grocery store patrons and moviegoers park there in the evening.

Misunderstanding the principles of shared parking or rote application of the default values and factors provided in Shared Parking, absent professional judgment and knowledge regarding specific local conditions, can result in unrealistic projections. The methodology and recommendations should be considered simply a starting point for the analysis of shared parking by experienced and knowledgeable professionals.

Forest City Commercial Development recognized the need to differentiate Victoria Gardens in Rancho Cucamonga from nearby retail competition. Montclair Plaza, a well-established enclosed regional shopping center, is located 12 miles (19 kilometers) west of the site, and Ontario Mills, a large enclosed outlet mall, lies only three miles (4.8 kilometers) south. Accordingly, plans evolved into a pedestrian-friendly, open-air, mixed-use design.

The vast parking lots necessary to support Victoria Gardens were incongruous with the pedestrian-oriented streetscape of a true downtown. To address this situation, three parking garages were built in addition to parking fields during the first phase. As the project expands, many of the first-phase parking fields will be occupied by buildings, and additional parking structures will be built.

Structured Parking. Parking structures are often built when surface parking is not, or is no longer, the highest and best use of the land. Other uses such as apartments, condominiums, office buildings, hotels, additional stores, or commercial recreational facilities may replace surface parking, making it necessary to provide structures for existing and any additional parking. The addition of parking structures to a mixed-use project should be seen as an opportunity to increase the project’s possibilities. For example, the ground level of a structure can accommodate service and retail tenants in reasonable minimum depths. Single-sided residential or office uses that will further enhance a project’s streetscape can also be used as a “veneer” on parking structures.

Parking structures can also alleviate excessive walking distances between parked cars and the stores in centers and solve space problems that may be created by a shopping center’s development or its later expansion. At many centers, adjacent land for expansion of the parking area is not available or has become so costly that building a parking structure or deck may be the most economical means of providing additional parking spaces. A parking structure can be built closer to the stores, and it can be depreciated, whereas land cannot.

A parking garage requires a ramp system, overhead clearances, column spacing, and ventilation for those parts of the structure that are below grade. The most common ramp system in North America is the single-helix or scissors ramp—a continuous ramp whereby sloping floors with aisles and parking spaces along both sides of the aisle provide access to the parking spaces themselves and the facility’s circulation route. The slope of the ramps should be carefully considered. Ramps with parking spaces and a maximum slope of 5 to 6 percent are acceptable. For nonrepetitive short segments or in hilly areas where people are accustomed to steep grades, parking floor grades up to 7 percent are acceptable. In any event, the needs of persons with disabilities must be considered in establishing parking floor grades. Greater slopes of up to 12.5 percent grade should be used only for speed ramps (nonparking ramps).11

Structural solutions that provide for the most open, column-free parking areas are the most desirable. The height or number of floors constructed in a garage should also be carefully considered. Too many levels and turns in a garage are confusing to customers. Parking structures with large areas of flat open parking closest to the retail center and fewer levels are the most desirable.

The interior environments of structured parking should be carefully considered to provide an open, clean, bright, and inviting atmosphere with clear signage for customers. The sense of security makes all customers willing to park in spaces farther away from entrances, while uninviting environments cause customers to leave the project with an undesirable memory of their shopping experience. Misfortunes to patrons range from vandalism and car theft to muggings. Although these same crimes can and do occur on surface parking areas, particularly in those areas most isolated from the shopping center, customers tend to perceive structured parking as potentially riskier than surface parking. Closed-circuit television cameras, communications systems, windowed stairwells, adequate lighting, and the visibility of security personnel can help improve safety.

Parking Lot Design and Layout. Certain key factors must be considered when planning a new or redesigned parking lot to make the most effective use of available area:

No standard formula exists for taking all factors into account. The approach varies from case to case and requires special expertise.

Convenience should be the guiding criterion for the actual parking layout at any center. Parking must be simple, trouble-free, and safe. Shoppers should be able to move confidently through the parking area without ever having been there or knowing the layout in advance. Landscaping can break up the amount of paved surface as well as provide shade and reduce heat gain— considerations that should be seen as an opportunity to enhance the shopping experience. As a rule, achieving smooth traffic circulation at a shopping center requires the advice of a qualified parking or traffic consultant.

How far the parking fields are from a center’s entrance contributes greatly to the notion of convenience. Generally, walking distances should be kept to a minimum. Based on the level-of-service (LOS) approach similar to the traffic engineering profession’s classification system to gauge acceptable congestion, LOS A for the distance that shoppers must walk is no more than 350 feet (105 meters) within a surface parking lot and 300 feet (90 meters) in a parking structure. LOS A for the distance from parking to destination is no more than 400 feet (120 meters) if both the parking and the destination are uncovered, 500 feet (150 meters) if parking is outdoors but the destination is covered, and 1,000 feet (305 meters) if both are climate controlled. These distances can be doubled and still be considered good (LOS B).12

Limited on-street parking serves as a buffer between pedestrians on the sidewalk and the vehicular traffic in the street. Wide sidewalks and narrow streets aid in the creation of a pedestrian environment at Clayton Lane in Denver, Colorado.

Clear signage provides not only directions to parking but also information about the availability of parking, allowing visitors to make quicker and more efficient entrance to Bayshore Town Center in Glendale, Wisconsin.

Circulation for cars in the parking fields should be as continuous as possible, preferably one way and counterclockwise. Drivers should be able to maneuver in the site without entering a public roadway. In a regional center, parking area circulation requires a dedicated roadway (a “ring road”) around the edge of the site and another around the building cluster. The inner ring allows for fire and emergency access, deliveries, and dropoff and pickup of customers.

Few outside the parking industry understand the magnitude of the cost of parking for a development. Even developers who have only dealt with surface parking in the past are often surprised if not shocked by the cost of structured parking.

The accompanying table presents a comparison of the typical costs to own and operate surface-lot and structured parking spaces in the United States. This analysis is based largely on a more detailed discussion of the topic in the Institute of Transportation Engineers’ Transportation Planning Handbook, with cost figures updated to 2004 dollars.1 The assumed operating expenses also reflect a more recent survey of parking facility owners.2 Obviously, numerous factors can significantly alter the costs of owning and operating parking; these figures are simply typical, illustrating the incremental costs for structured parking.

Where land is inexpensive, it is clearly more economical to build surface parking. In more urban settings, development is often actually redevelopment, and land values will reflect the buildings that are already present on the site and the potential future return on an investment to redevelop it. Of course, the developer’s overall decision regarding redeveloping land in such circumstances will hinge on the overall rental/lease opportunities and return on investment. But a decision to use structured parking instead of surface parking will be driven primarily by the availability of land. And if it costs $300 per space per year to collect parking fees for a 500-space facility, at least $25 per space must be collected each month to make it worthwhile to charge for parking before one even begins to recover the increased capital costs of structured parking. When a developer can purchase land in an undeveloped area for less than $50,000 per acre ($1 per square foot), it is obvious why free surface parking is the norm in suburban development. It does not reflect a conscious philosophy by the development community to design for automobiles rather than people, but rather simple economics.

FIGURE 4–1

Assumptions:

Underground structure is short-span (30 x 30-ft. column grid) owing to construction above. Above-grade structure is long-span (20–45 ft. x 50-60 ft.).

Surface lot size increased by 10% for landscaping, setbacks, access, etc., typical of suburban location; above-grade structure site increased by 5%; underground structure not increased.

Construction cost based on average design costs across United States in 2004.

Project costs increased 15% for design and other miscellaneous soft costs.

Term for financing: 20 years. Cost of funds: 5%. (These figures used to determine annualized cost to own the facility.)

Basic operating costs include utilities, insurance, supplies, routine and structural maintenance, snow removal, etc.

Surface lot has lower utilities but six times the snow removal cost of above-grade structure. Below-grade structure has no snow removal but higher utilities for lighting and ventilation.

Surface lot assumed to be in suburban location with free parking and no security. Underground structure will have higher security than above-grade parking structure.

Where land is expensive and property must be more densely developed to make a project economically viable, above-grade structured parking is the norm. When developers own and operate structured parking, which in Figure 4–1 involve more than five times the costs of owning and operating surface parking, they have a much greater incentive to more carefully scrutinize how they plan, design, and manage the parking resource. In turn, those with structured parking are more likely to charge users for some or all of the costs of parking.

Underground parking is significantly more expensive, to the point where there is little economic incentive to choose it except in the most densely developed areas of the largest cities. These urban areas are strongly served by public transit, and thus there are natural market forces setting the price of parking, which in turn affect both commuter and consumer travel-mode decisions. That said, if underground parking is the only viable option, there is strong incentive to minimize its capacity while maximizing its use and revenues, all of which can be accomplished by shared parking analysis.

Numerous factors other than cost affect parking development decisions, not the least of which is how much property can be acquired and what lease rates can be obtained for the occupied space. Even where land costs are lower, sites of restricted size or shape may dictate structured parking. Ultimately, the potential return on investment in a project as a whole is what drives developers to choose to develop or not develop a particular site. For retail, restaurants, and service businesses, the potential return on investment also drives tenant decisions to locate in a particular project, whether or not parking will be surface or structured and paid or free to their employees and customers.

Notes

1. Mary S. Smith, “Parking,” in Transportation Planning Handbook, 2nd ed., ed. John D. Edwards, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Transportation Engineers, 1999).

2. Jon Martens, “The Art of Maximizing Your Profits,” The Parking Professional (September 2004), pp. 22–25.

Source: Excerpted and adapted from Mary S. Smith, Shared Parking, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: ULI-the Urban Land Institute and the International Council of Shopping Centers, 2005), 139-141.