The rotunda of the Westfield San Francisco Centre in San Francisco, California.

The shopping center industry is constantly changing. Retailers change their formats, their products, and sometimes even their targeted customers. Shoppers change what they want to shop for, how they want to buy it, and the experience they want when they shop. Municipalities and their residents change their opinion about the desirability of retail projects in their cities and towns, what form these projects should take, an acceptable size for retailers (some have barred stores larger than 150,000 square feet [14,000 square meters]), and the affordability of housing in a mixed-use project, with concerns most recently focused on workforce housing. These sea changes require shopping center owners to continually update the tenancy, layout, and appearance of their centers. Sometimes they invest in their centers to capitalize on these changes and convert them to profit-making endeavors. In other cases, this investment is necessary as a defensive measure to preserve value.

Although change in the shopping center industry comes in many forms and is shaped by many forces, the underpinning of the industry comes down to one single dynamic: the rent (or land price) a retailer can afford to pay in any given location is based on sales it can generate in that location. The greater the sales, the greater the rent the retailer can afford and still be profitable, regardless of most other factors. Generally speaking, a retailer can afford to pay more rent in a high-sales location—even if it is operating from an old store with an outdated format and inadequate parking—than it can pay in a lower-sales location with a new prototypical store and plenty of convenient parking. Although a safe, attractive center with adequate parking facilities generally encourages sales, these characteristics alone by no means guarantee a retailer’s success.

In short, the successful expansion and rehabilitation of any center is mainly about increasing (or at least preserving) retailers’ sales. Expenditures that increase retail sales or attract retailers with strong sales pay the most dividends. Expenditures on features that reduce operational costs or enhance appearance are not unimportant, but a shopping center without successful tenants has lost its reason for being.

A myriad of factors lead to this constant change in the shopping center industry and the need for every owner to continually consider rehabilitation, expansion, and reconfiguration of existing shopping centers:

Santa Monica Place, in Santa Monica, California, opened in 1980 as an enclosed mall. In 2008, Macerich began the process of taking the roof off, creating an outdoor central courtyard, and retenanting. Key in the redevelopment of this older mall was making a connection with the community around it, particularly with the three-block pedestrian portion of Third Street (the Third Street Promenade), which starts directly across the street and is a well-established and lively Main Street shopping, dining, and entertainment district. A series of public workshops helped the developer to arrive at a plan the community would accept and support.

These long-term forces reflect a new retail environment that requires a more dynamic approach to maintaining the competitive position of shopping centers in the early 21st century.

This chapter outlines the most important issues regarding redevelopment of existing centers. Many of the subjects discussed in the earlier chapters about project feasibility, financing, and planning and design are applicable to this discussion of expansion and rehabilitation. The previous chapters provide background details, and readers should refer to them as well.

This nine-tenant, 24,000-square-foot (2,230-square-meter) convenience center originally built in 1956 was transformed to become a local landmark. Rental rates at Wykagyl Shopping Center in New Rochelle, New York, are now twice what they were before renovation.

In deciding whether to undertake the rehabilitation, expansion, or reconfiguration of an existing center, the owner must determine whether the potential return on investment justifies a new program. The first step is to examine a number of historical and current factors, both internal and external. Internal factors include tenant sales performance, the historical financial performance of the property, tenant mix, tenant lease terms, the center’s market share and its relative position in its market, existing management, the availability of land for expansion, and physical condition of the property, including the condition of buildings, utilities, landscaping, and site improvements. External factors include composition of the market and how it has evolved during operations thus far, the retail potential reflected in expenditures in the market, competition and its impact on the center, potential new competitors, the availability of new tenants to improve or expand the center’s tenant mix, and an estimate of the size and timing of the proposed changes. These factors can then be evaluated in terms of the specific investment criteria established by a shopping center owner to test the financial feasibility of a proposed rehabilitation and/or expansion.

Sales are the shopping center’s most important report card; they hold tremendous secrets for those who learn how to read them. Unlike the developer of a new center, who has to work with estimates, the “redeveloper” of an existing center already knows the sales performance, rents and lease terms, and individual tenants’ capability for management. To diagnose the need for rehabilitation, the developer can begin with trends in sales performance over a five- to seven-year period (or whatever is available). Total sales for the center and a comparison with those of similar retailing centers in the region are usually the first indicators of whether and to what degree to rehabilitate, reposition, or expand the center. It is important to understand key events that may have affected sales: for example, closing a highway exit for repairs may have caused a drop in sales, or the opening of a supermarket in the long-vacant anchor space may have resulted in increased sales.

More important, however, is an analysis of individual tenant sales. Always start with the anchors, as they typically drive the center’s sales, but look also at the sales of smaller tenants. Several aspects of sales are key:

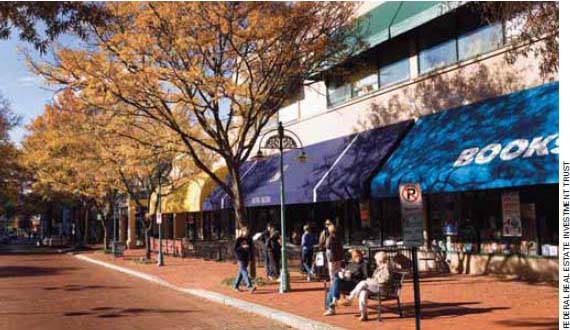

The Village at Shirlington in Arlington, Virginia, was ahead of its time when it reopened in the 1980s with its Main Street configuration. With 284,000 square feet (26,400 square meters) of retail space, it ran along both sides of a single block on 28th Street South and included a cinema and a 150,000-square-foot (14,000-square-meter) Best Buy. These two large tenants formed a terminus at the end of the one retail block. Federal Realty Investment Trust purchased the property in 1995 and began a five-phase expansion and redevelopment plan that included demolishing the by-then defunct big box, extending 28th Street, and attracting a major supermarket as a new anchor.

Federal Realty changed the merchandising mix of this older community center to focus on restaurants and food stores and introduced a cultural component by including a performing arts theater and a library. Street furniture and outdoor dining areas at the Village at Shirlington in Arlington, Virginia, were easily accommodated by the original street widths.

The answers to these questions will help devise an optimal tenanting and merchandizing strategy and can promote guidance in the pursuit of releasing.

The next step in determining the feasibility of repositioning a shopping center is to review tenants’ existing leases to determine:

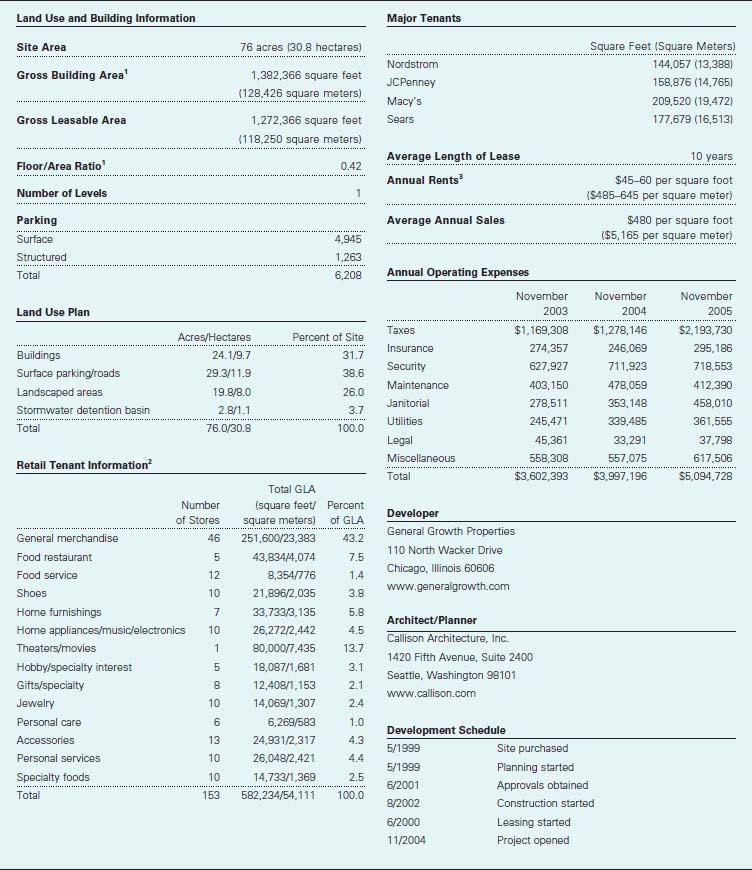

Alderwood, a 1.5 million-square-foot (139,355-square-meter) traditional indoor mall in Lynnwood, Washington, about 15 miles (24 kilometers) north of downtown Seattle, has been transformed into a multifaceted entertainment and retail center. By adding two intensively developed outdoor shopping areas, a cineplex, and restaurants, owner General Growth Properties (GGP) hopes to capture more of the growing high-end market for the Seattle region. The intent is to reposition the 25-year-old mall as a true regional destination. As a result of the changes, the mall has shifted its cultural base, relying less on local residents who make quick stops and more on visitors who spend a greater part of their day and a larger share of their discretionary income.

The outdoor additions, with a design that involves complex massing and incorporates elements of international street and plaza scenery, open the mall plan on two sides to the outside. Concepts from contemporary hospitality and resort trends—including lavish paving and outdoor artwork—are incorporated as well. The repositioning of Alderwood includes phased construction of a new anchor store for Nordstrom and two parking decks. Construction of all new elements was completed in fall 2004.

On one side is the Terraces, a 103,000-square-foot (9,600-square-meter) multilevel, intensively landscaped outdoor plaza extending from the mall’s indoor food court to a new parking deck; the 80,000-square-foot (7,430-square-meter) cineplex structure is located at the edge of the site. Four new restaurants, attached and freestanding, are located in the Terraces.

The Terraces opens out from the south side of the mall to an intensively landscaped area bordered by freestanding restaurants and a new 16-screen cineplex. A massive, cantilevered canopy shelters a sitting area and a two-way stone fireplace.

On the opposite side of the mall, two interior corridors now extend through large glass doors into the Village, five irregular blocks of stores designed around a small series of streetscapes and open plazas. The 187,000-square-foot (17,400-square-meter) Village outdoor addition has 40 new retail tenants and three new restaurants. It presents a new, inviting, urbanized aspect to Alderwood.

These additions increase gross leasable area at Alderwood from 1,039,984 square feet (96,618 square meters) to 1,272,366 square feet (118,207 square meters). Parking, including 1,263 spaces in two new structures, now totals 6,208 spaces on site. The 16-screen entertainment complex will seat 3,800 stadium style.

After this review, the owner should obtain early termination of poorly performing tenants that are not suitable for the center’s new market position. Tenants that are losing money may be willing to agree that the landlord can terminate their leases at any time with a few months’ notice. An attractive buyout offer may be necessary for some terminations.

Originally opened in 1979, Alderwood is anchored by Nordstrom, Macy’s (originally Bon Marché), Sears, and JCPenney. It underwent cosmetic improvements in 1995 under then-owner DeBartolo Company, which exposed the steel trusses and gave the mall a more industrial character.

GGP began managing Alderwood under contract with DeBartolo in 1997. Emerging census data and demographic research clearly show an influx of population to the northern neighborhoods of Seattle and nearby suburbs to the north and east. The same data show that average household income levels are rising. According to 2003 data for the ten-mile (16-kilometer) radius trade area, household income averages $75,000, the median age is 37, and the population is 680,000 and growing.

As GGP began amassing these data, lease rates and occupancy remained generally steady; the existing 309,000 square feet (28,700 square meters) of mall shops was 95.1 percent occupied as of December 2000. Using reports from tenants, however, the company determined that consumers in the trade area were leaving to shop in Seattle and the East Side, particularly in the newer open-air centers.

GGP concluded that Alderwood stood to gain substantial market share and to become one of three regional malls — along with Bellevue Square and University Village—that serve the most affluent sector of the Seattle metropolitan area. The company purchased Alderwood from DeBartolo in May 1999.

The original 1979 enclosed mall, shown in tan, was anchored by five department stores, four of which are shown here. The fifth declared bankruptcy in 2000, and Nordstrom purchased that site to construct its current store. Outdoor shopping areas the Terraces (on the southwest corner) and the Village (on the north side) were added in 2004. The Village was constructed on the original Nordstrom site.

GGP began working with Seattle-based Callison. The general objectives of the redevelopment plan were to increase leasable retail space, capture market share among affluent area residents, and position Alderwood to command higher rents throughout the complex. In addition to adding entertainment, restaurants, and outdoor space to the existing mix of retail stores and a food court, strategies included clustering retail stores to fit different shopper profiles and merchandise categories.

To reach the underserved target market in the area, the company began working with a handful of potential tenants, including Pottery Barn, Borders Books, Williams-Sonoma, and Gene Juarez Spa. These companies had a corresponding interest in opening new locations at Alderwood and contributed their own market research supporting GGP’s investment decisions. Three national theater chains also expressed interest in Alderwood.

The owner and design team initially explored the idea of increasing leasable area by adding a second level to part of the mall. But this solution proved impractical, and the owner decided to use some of the acreage devoted to parking around the enclosed mall to create an outdoor pedestrian environment and connect it to the existing mall structure.

Increasingly, GGP believes that consumers’ interest in outdoor shopping is becoming stronger. Using images and storyboards, GGP conducted research among consumer focus groups that supported this belief. Research also showed that the Seattle area in particular views itself as an outdoor market. The success of Flatiron in Broomfield, Colorado, which has both indoor and outdoor components, and many other outdoor malls—including University Village in Seattle and Redmond Town Center east of Seattle—confirmed GGP’s commitment to developing outdoor shopping at Alderwood. It would be transformed from a typical dumbbell-shaped enclosed mall to a lifestyle center where visitors can enjoy a variety of experiences in addition to shopping.

As the concept for Alderwood took shape, Nordstrom made known that it wanted a new physical plant in the mall. Then in 2000, Lamont’s closed its store after filing for bankruptcy and liquidation. GGP purchased the Lamont’s store and pad to increase the possibilities for expansion.

The closed anchor store became a key opportunity for redevelopment and a critical link in phased construction of additions to the mall. Nordstrom built its new store on the Lamont’s site and now owns the land and adjacent parking as well. The old Nordstrom pad, in a key location on the west side of the mall, became the construction site for the Village, one of two key outdoor shopping areas added to the mall.

GGP built the shell for the cineplex as a typical build-to-suit transaction and will retain ownership of the land. Loew’s was responsible for installing screens, seats, and other special features.

Enhancements in the existing enclosed mall, including new ceiling panels, comfortable seating areas, and changes to the color palette, complement the new construction outside and just inside the entrances to the mall.

The owner should then consider desirable tenants whose leases expire within the next two to three years and who have no options to renew. If these tenants’ operations are profitable and they want to stay in the center, then the owner should be able to renegotiate their leases and raise their rents to current market rates in return for an extended term.

Most leases for inline tenant space give the landlord the right to relocate the tenant to new space if the new space is comparable with the old space and the landlord pays the costs of relocation. The owner must, however, budget for moving and buildout costs for relocated tenants. And concessions may be needed to placate tenants that are being moved.

Even tenants with substantial remaining lease terms or options to renew and no relocation obligation can usually be persuaded to move to a new location when a center is rehabilitated. The promise of a better-performing center and a short-term rent abatement or reduction may provide the motivation that these tenants need to cooperate with the overall repositioning strategy.

In terminating tenants and re-leasing space, however, the owner must keep in mind requirements for cotenancy that leases of the most desirable tenants usually contain. These provisions give the tenant the right to reduced rent or termination if too few stores in the center are open and operating. Before major center rehabilitation, the owner should reach an agreement with these tenants that, for example, allows more store closures in return for the payment of a percentage of sales rather than a fixed rent.

In anticipation of rehabilitation, the owner may wish to offer only short-term leases or leases that permit the owner to terminate the tenant with a certain amount of notice. The owner should be aware, however, that a tenant is not likely to invest in attractive tenant improvements or operations if it is not assured that it will have a long term to recoup its investment. If the owner wishes to enter into traditional long-term leases even though it is contemplating substantially changing the center, it should include certain provisions in new or renegotiated leases that, for example, would provide for increased rent if the inline space is upgraded or enlarged or if another anchor is added. An owner with a strong negotiating position may also be able to include a requirement that the tenant remodel its storefront to the new standard for the center when rehabilitation starts. The leases should also expressly allow the landlord to add square footage or parking decks or to change the center and its common areas without approval, and to relocate tenants. An owner contemplating redevelopment should be very wary of a strict cotenancy provision unless it will not take effect until some designated time in the future.

Most important, an owner contemplating redevelopment should negotiate with existing tenants to obtain as much flexibility as it needs to effect rehabilitation and should draft its new and renegotiated leases to ensure that it has this flexibility for as long necessary to complete the job.

An existing center provides the opportunity to conduct direct market interviews. Interviews of customers can reveal the public’s reaction to such matters as image, design of the center, range of tenant types, quality of individual tenants, and the center’s strengths and weaknesses in terms of customers’ preferences. Such interviews also reveal how responsive customers are to marketing and who the center’s competitors are. Data obtained from such interviews, if they relate to social and economic characteristics of the trade area in general, can provide information on delineation of the trade area, penetration of the market, market shares and distribution (geographically and by economic groups), and customers’ habits, preferences, and tastes.

Properly structured and conducted, interviews can reaffirm or refute the need for rehabilitation.

The center’s potential for physical expansion should also be considered, generally for at least one of three possibilities: developing a portion of the existing parking area, developing outparcels, or developing parts of the common area that do not involve parking.

Inappropriate parking standards used for many older centers have resulted in a surplus of parking spaces, even during the busiest hours of the year. Such surplus space could provide additional income-producing areas.

In many locations, particularly in urban areas, increasing land values underneath parking lots and outparcels justify increasing the density of development and consolidating parking into structured or underground lots. This situation opens opportunities to expand the size of the shopping center, add a mix of uses—residential, office, cultural, hospitality—that will bring new customers to the center, link the center to the surrounding community, permit new retail formats and environments, enhance access for pedestrians, and create more focus for the community.

Because nonretail uses may experience peak demand for parking at times other than that for retail uses, the development of nonretail uses may make it possible to create additional leasable space without the accompanying demand for much additional parking (see Chapter 4 for a discussion of shared parking).

Blank department store walls can be lined with small, high-rent shops, and tenant spaces can be reconfigured to increase the number of tenants or their size. Although many renovations involve subdividing larger stores into smaller ones, the opposite is also possible if the center needs to accommodate off-price or value retailers or specialized entertainment attractions that need larger space.

Sierra Vista Mall in Clovis, California, an existing enclosed mall, was reinvigorated through an expansion and remodeling in response to changing demographics. A portion of the mall concourse was demolished to create a plaza for the new outdoor component.

Trade areas are in constant flux, growing or shrinking vertically and horizontally, and the decision to rehabilitate or expand a center rests ultimately on an analysis and forecasting of external factors. For instance, the center’s locational value should be reassessed based on current and planned residential expansion, demographic changes such as income and lifestyle, other commercial developments, and road and highway improvements in the trade area.

The geographic limits of a trade area should be tested to understand where customers currently come from: asking management of anchor stores is a great way to get a quick handle on this information. Understanding the trade area’s boundaries and its demographic makeup largely dictates what sales tenants will achieve at the center.

Changes in the composition of neighborhoods should be examined for both positive and negative signs. Statistics such as population, income, ethnic background, education, and profession should be examined, as retailers use them to predict potential sales in a given location. For instance, a supermarket requires a certain population within one to two miles (1.6 to 3.2 kilometers) to provide enough shoppers, and a bookstore operator might look at how many people in the trade area are college educated as a proxy for those who buy books. Psychographic information that describes the lifestyle and behavior of the population, further discussed in Chapter 2, are also important indicators.

In short, the market analysis identifies who potential customers are, where they currently shop, and which of their needs are not being met. It also identifies who current and future competitors are and what needs they serve compared with the center considered for rehabilitation. Based on a thorough market analysis (see Chapter 2), a number of hypotheses for expansion or rehabilitation can be developed. For example, if the market analysis reveals that the addition of an anchor store would benefit the center by attracting other nonanchor tenants and reducing customers’ shopping elsewhere and land for it is available, the owner can explore this alternative.

Although a sophisticated developer might be able to convince a retailer to consider a particular site, for the most part retailers use their own extensive research tools to determine whether or not a site is desirable. A retailer will probably develop a sales model that looks at the size of the market, current per capita expenditures for the retailer’s goods, and an estimate of the percentage of market sales the tenant could capture in the location being investigated. Although it is important for the developer to understand the market and the competition, if the tenant’s projections indicate the location will achieve strong sales, it is an easy sell, but if the tenant does not project strong sales in a location, it will be very hard to convince the tenant otherwise.

Once the developer understands the factors the market analysis highlights, he or she can evaluate various scenarios for rehabilitation. Cost estimates developed for the proposed alternatives provide the basis for a financial pro forma.

A financial analysis is the final step in deciding what to do with an older center. The pro forma financial analysis should include the following elements:

The additions to Alderwood represent an important trend toward regional connections in the design of shopping centers and away from the standardized and hermetically sealed environment of enclosed malls. With shops in the Village and the additional dining options in the Terraces, Alderwood appeals to an upscale market and offers a lifestyle center. Eclectic, urban architecture combines with the seasonal and daily rhythms of outdoors.

On one corner of the site, a large theater and parking complex create a new outdoor perimeter for the mall complex and establish boundaries for the Terraces, an intensely landscaped outdoor area that connects with the food court in the existing mall. Three freestanding restaurant buildings complete the composition. On the opposite side of the mall, two of the mall’s interior corridors extend through glass doors into the Village, five irregular blocks of stores designed around a small series of streetscapes and open plazas. From the surrounding arterials, the Village adds exciting, human-scale detail to the superscale presence of the existing mall.

Additions to the mall were planned in concert with a slate of cosmetic improvements to the existing indoor areas. To promote visual unity and identity, some of the design vocabulary of the new outdoor areas extends into the enclosed mall through new and expanded glass doors and glass walls. The architecture of the new additions is based on a number of design strategies that draw in visitors and sustain excitement throughout the complex:

The shifting axes of the streets in the Village give a sense of discovery to the five irregular blocks of stores, designed around a small series of streetscapes and open plazas. Extra features like this trellis and seating area blur the hard lines between the outdoor and indoor environments.

Clayton Lane in Denver, Colorado, is a redevelopment of a 1954 Sears Roebuck site, converting the 650-car surface parking lot into a mixed-use retail district. Before obtaining financing, the developers had to negotiate construction impact mitigation and logistics for the fully operating Sears and a newer Whole Foods store. For example, the renegotiated Whole Foods lease required providing temporary loading docks and a shuttle to off-site parking for employees during the first phase of the project.

A financial pro forma developed along these lines provides a first-cut framework for deciding whether, how, and to what extent to rehabilitate the existing center. Most pro formas look at the value created by the property’s projected NOI after redevelopment and compare it with the cost to achieve the value of the higher NOI. The analysis is relatively straightforward, involving the use of capitalization rates (see Chapter 3) and the addition of any sales income from for-sale components added to the project with the rehabilitation.

For example, assume a property that the developer purchased for $5 million has a current NOI of $500,000. How does an owner evaluate a redevelopment plan that costs $2 million and would add $300,000 to NOI? This evaluation can be made on the basis of total value or on incremental value:

This analysis is simplistic, but it does illustrate some of the basic concepts an owner should look at when performing the financial analysis for a redevelopment. A complete financial analysis takes into account a great many more factors (see Chapter 3 for a full discussion of how to determine financial viability). Given the changing nature of the shopping center industry, owners could have a waning or obsolete asset, in which case an investment must be made not to increase value but to preserve it.

If the scope of the redevelopment allows the shopping center owner to pay its costs from cash flow, then no outside funding would be required. Redevelopment of most centers, however, requires outside funding in the form of debt, equity, or some combination of the two.

The how-to’s of securing debt and equity are well covered in Chapter 3, so only a few additional issues particular to a shopping center redevelopment are mentioned here:

The developers of Clayton Lane in Denver, Colorado, overcame significant resistance from neighborhood groups concerned about many aspects of the project: height, massing, and design; its potential impact on traffic and parking; and the merchandising strategy. To address these concerns, the developer met with seven neighborhood groups, including a citizens’ committee, an official city-appointed design review board, and the decision-making body for commercial interests.

All but the most nominal renovations and expansions require the developer to secure approvals from the necessary government jurisdiction. In some cases, the approval process is relatively smooth, especially if the center is in distressed condition or needs modernization. In other cases, expansion of a center is subject to massive public scrutiny as citizens and public officials provide reactions and input in the development process.

To secure the necessary government approvals for rehabilitation or expansion, some or all of the following steps may be necessary:

Similar to the process for new projects (see Chapter 2), a developer often first submits a basic concept plan, avoiding the expense of putting together a detailed site plan until the jurisdiction indicates that the project will likely be approved.

Moreover, as for new projects, a community will be concerned primarily with the elements of a shopping center pertaining to the community’s general welfare. Major considerations often include the effects of competition on existing retail operations (or other retail centers in the community), traffic, noise, required utilities and infrastructure, and environmental impact. Increasingly, communities also worry about the aesthetic qualities of a shopping center, how the center will affect the character of the surrounding community, and how well it will be integrated with surrounding neighborhoods. If a developer is sensitive to these concerns and designs an attractive center that is compatible with its surroundings, the approval process will likely be much easier.

An innovative 50-50 partnership between Forest City Development and The Westfield Group created Westfield San Francisco Centre, which opened in the Market Street district in September 2006. Forest City managed project development until 2002, including securing entitlements and completing designs. Westfield acquired the adjacent San Francisco Shopping Centre and finalized plans with Forest City to connect and integrate the two sites in 2002. Westfield managed development during construction, including construction management, leasing, and tenant coordination. It now manages day-to-day operations of the combined center.

A developer needs to very carefully address specific community concerns. The developer, for example, should justify the need for an increase in the area’s shopping facilities as well as the proposed change in the center’s types and amounts of goods and services. The development team should be prepared to discuss the center’s architectural design, the lighting necessary for safety and security, signage, traffic circulation, and the relationship with adjoining properties. The developer’s aim should be to create a shopping environment that is popular with the community it serves, fills a niche, and reflects an understanding of consumers’ shopping needs.

A well-planned, well-documented presentation at public hearings improves the developer’s chances of obtaining community support. Photographs, statistical charts, drawings, and models make presentations more vivid and comprehensible.

The developer should also want to promote good public relations during the approval process. A community frequently needs reassurance when it is in the midst of transition to a more urban setting. The developer can provide this reassurance by alleviating anxieties that might have been caused by the negative consequences of past development and by demonstrating how the proposed development will enhance the community. Zoning favorable to shopping center expansion may be in place, but developers still must carry the burden of proof and provide sound reasons for a project’s approval.

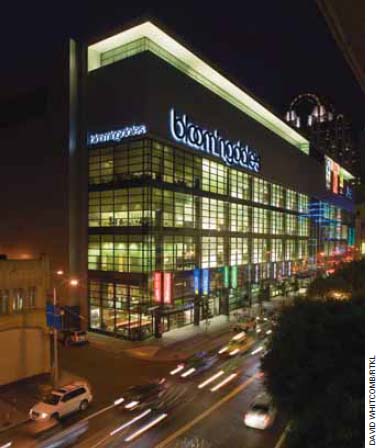

The 1.5 million-square-foot (140,000-square-meter) Westfield San Francisco Centre is partially located on the former site of the historic Emporium Building. When the eight-year, privately funded development process began, The Emporium was boarded up along Market Street, and the rear storage area on Mission Street featured graffiti. A year-long process restored the Market Street signature facade to its 1908 appearance in compliance with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, complementing the street’s rich architectural heritage. The Mission Street entrance now highlights the 338,000-square-foot (31,400-square-meter) Bloomingdale’s and features a modern, jewel-box design.

The two structures that make up the Westfield San Francisco Centre in San Francisco, California, are linked on five levels. The restored dome and rotunda on the fourth floor provide convenient access to the first floor of Nordstrom and the top floor of Bloomingdale’s. This innovative circulation diagram was made possible by raising the Emporium’s dome, an engineering feat that required nearly a year to plan.

The changing nature of both retailing and the shopping center industry requires the owner to always have an eye open to considering change in a center’s physical makeup. First and foremost, any change will be dictated by the anchors’ performance and viability. If the anchor tenants are performing well, then a center may be able to prosper for some time with little change or additional investment. Similarly, a failing or closing anchor could require significant new investment or changes, even in a center that has been recently renovated.

Updating can range from cosmetic improvements to complete rebuilding. If the developer decides to proceed with physical rehabilitation and expansion, detailed plans are required that consider every aspect of the property— all interior and exterior components of the structures, and all site elements such as access roads, parking, and landscaping. Although not all elements and components will require physical changes, each must be examined as part of the comprehensive redevelopment to determine which upgrades are required to achieve the envisioned design concept and draw the targeted customers.

The condition of existing buildings must first be studied to determine the amount of functional rehabilitation needed. Signs of deferred maintenance must be corrected, and buildings must be made to comply with building codes. A developer considering the acquisition of an older center for rehabilitation and expansion would likely meet with the local building inspector to get some idea of the extent of rehabilitation necessary to correct existing problems with the overall structure, roofs and skylights, elevators and escalators, entrances and exits, storefronts and signage, flooring, plumbing and the sprinkler system, the HVAC system, lighting and sound systems, security systems, restrooms, merchandise delivery and trash removal systems, and access for handicapped patrons.

Walkways in older strip centers may need to be widened, narrowed, resurfaced, or reconfigured. Waterside at Marina del Rey, California, had not been renovated for 15 years, a longer period than is typically required to stay competitive. Updating the 130,000-square-foot (12,000-square-meter) 1960s strip center included adding 10,000 square feet (930 square meters) of retail and restaurant space and an outdoor dining and patio area.

The development team must then determine the extent and nature of aesthetic rehabilitation needed to improve the center’s overall appearance and general shopping environment. Today more than ever, a shopping center’s environment is critical to its success, as customers have so many options for buying comparable merchandise. Both the exterior and interior design should be examined for how up-to-date the center is, how well it reflects the desired image, and how attractive and convenient it is for shoppers.

Redevelopment of older, enclosed malls often involves partial or complete “demalling,” or opening up to draw customers in from the sidewalk, to create livelier retail districts with streetfront retailing, and to provide a type of shopping experience that, although new, is reminiscent of older, mid-20th-century downtowns. Adding other nonretail uses can transform a shopping center into a town center in the appropriate location. Alderwood Mall, an enclosed late-1970s mall in Lynn-wood, Washington, opened in late 2004, underwent a makeover that included the addition of two intensively developed outdoor shopping areas, one that connects with the food court in the original mall and the other connected to the interior corridors through large glass doors. Belmar, a mid-1960s enclosed mall in Lakewood, Colorado, was completely demolished and reconstructed as an open-air shopping district in 2004 with residences and offices over retail (see the Belmar case study in Chapter 9 to understand the complex series of steps undertaken on this project).

Redevelopment of existing smaller-scale, open-air centers often involves a transformation to upscale, aspirational retailing with significant architectural enhancements, and clusters of fine dining restaurants and entertainment features. Brentwood Square, an early 1950s neighborhood strip shopping center, was outdated and functionally obsolete, with low ceilings, shallow stores, and poor site layout. After the acquisition of additional land, construction of almost three times the original space, introduction of a straightforward modern design, and retenanting with a varied collection of highly branded specialty stores, category killers, and an upscale supermarket, the result was a fresh, new 197,000 square foot community destination (see the case study in Chapter 9).

Built on a site once occupied by an enclosed mall, Belmar in Lakewood, Colorado, required rezoning for mixed uses, density, setbacks, and varying height limits that had never before been seen in the city. These issues were resolved through a special Belmar zoning district known as an official development plan. The ODP’s flexibility allows the developer to respond to shifting market demand rather than committing specific corners to a particular use.

Many developers have experienced the pain of having a project ready to launch, with a design specifically shaped to respond to a favorable market and strong financial backing, only to discover at the last minute that local residents are opposed to the development’s approval. Often, the project team may have overlooked signs of opposition, and now residents are discontented, convinced that their concerns are being ignored.

What the development team may not have realized is that local leaders represent another market for development projects, a market that needs to be engaged early to avoid derailment of even the best designs. In many communities, the days of relying on a team of consultants and attorneys to rush projects through a pro forma public hearing are gone. Community residents often tend to view public hearings as a charade, and they can be suspicious of developers’ motives and intentions.

Community fears about neighborhood change can be heightened by misinformation or a lack of information about proposed developments, which can result in a contentious climate for development.

Developers, on the whole, have grown to respect the potential strength of community opposition and its possible effects on their proposals. Many of them have seen designs torn apart and approval processes delayed by a project’s opponents. Learning from those experiences, many developers have adopted a more positive approach and seek to engage community residents early in the decision-making process.

“Community engagement” encompasses a variety of approaches to involving community residents in learning about, providing input to, and ultimately furnishing support for development. Public agencies increasingly seek community participation in decisions about growth and change. Developers also can employ community outreach strategies to help shape their projects in ways that meet community and market goals. By promoting a more collaborative approach, developers can work through issues and avoid surprises that can delay project approvals. In addition, developers’ participation signals a willingness to act as responsible citizens of the community.

Engaging a community in the development process begins with three questions:

Answers to these questions can come from interviews, surveys, data collection, reports, or informal chats with people in the neighborhood. Developers tend to be skilled in “walk-and-talk” information gathering and in checking out neighborhood conditions on the ground.

Determining the specific process for securing community involvement usually requires four steps:

The process can be held in settings or given formats that will encourage participants to expound their views and ultimately agree to support a plan or design. Design charrettes are popular and usually involve a series of facilitated, intensive discussions held during a relatively short time frame—often conducted over three to five days or two or three successive weekends. Discussions can be enhanced by illustrative sketches and designs produced during the charrette and can end—it is hoped—in general agreement on a concept plan or design.

Design charrettes or other types of sequential meetings may incorporate several types of events:

In addition to formulating a schedule of events, organizers of community engagement processes need to determine a location and the equipment required for each event, the choice and sequence of speakers, the ground rules to be followed during presentations and discussions, and assignments of support staff and facilitators of discussions.

Two classes of tools are indispensable in involving citizens effectively in development planning and design: a well-constructed communications strategy and graphic devices for illustrating proposed projects. A communications program is vital to achieving inclusive and productive participation. The program should include an initial alert to prospective participants about planned community engagement efforts; dissemination of basic information about the project and the highlights of current planning; and displays, broadcasts, briefings of agencies and groups, and other means of informing the community.

Particularly helpful in communicating plans and designs are illustrative tools to provide images of potential development outcomes, including drawings of proposed buildings and areas and computer-aided renderings of possible development scenarios or before-and-after comparisons, using aerial and ground-level photos. The illustrations can be displayed on large screens to facilitate discussions about the proposals and even vote on favored designs. Many planning and design firms now routinely use computer technology to picture stages of future development.

The public sector increasingly uses collaborative planning and design processes to reach agreement on community development issues. Developers can organize similar procedures to ensure a relatively smooth takeoff of proposed developments without the crash-and-burn possibilities that might otherwise loom over the proposals. The time, effort, and cost are likely to pay off in enhanced development and community goodwill.

Source: Excerpted from Douglas R. Porter, “Winning Community Support,” Urban Land, February 2007, pp. 148–149.

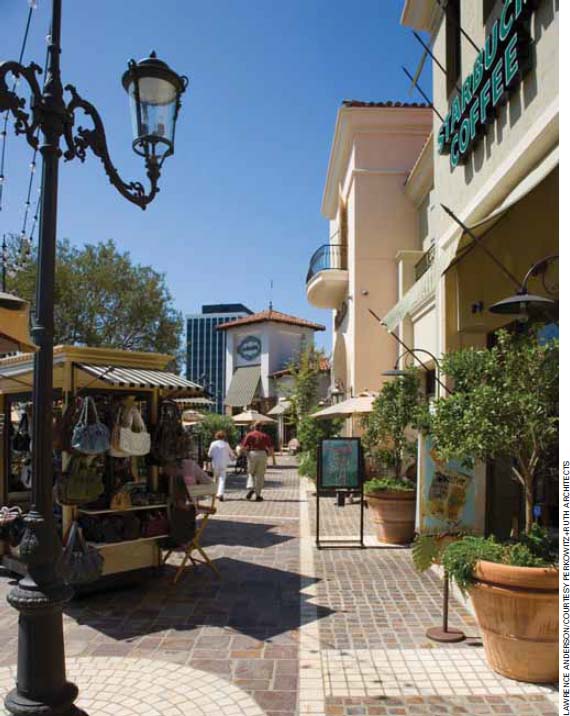

In general, for an older open center, it might be advisable to create varied facades, setbacks, materials, and signage along pedestrian walkways to add visual interest, surprise, and diversity to the shopping experience.

For older, enclosed centers where portions or all of the center remain enclosed, dark interior finishes, low ceilings, and minimal amenities might require a redesign that includes more architectural diversity, lighter finishes, higher-quality materials, skylights, more up-to-date signage and lighting, and more appealing interior and exterior landscaped areas and pedestrian walkways with fountains, art and sculpture, and seating areas.

Pedestrian surfaces in newer shopping centers are at once more varied and use higher-quality materials, so it is necessary to examine current walkways with that thought in mind. The developer also needs to determine whether walkways are adequate for the efficient and comfortable circulation of pedestrians. In older strip centers, walkways may need to be widened, narrowed, resurfaced, or reconfigured. In any case, the use of interesting and decorative materials should be investigated. Ordinary concrete can be made more interesting with brick or wooden spacers, or the concrete itself can be enhanced with color or stamped patterns or textures so that it resembles more costly materials. A high-end renovation might merit walkways made of brick, stone, or clay tiles. In all cases, a key factor in designing walkways and deciding which materials to use is safety. Slippery or otherwise dangerous surfaces must be avoided. Varied surfaces should be considered to differentiate sections of the shopping center.

The building’s facade offers the greatest opportunity for creating a new image that can help to reposition a center, and altering building facades is one of the easiest ways to dramatically change a center’s character and appearance. Options to consider range from a minimal program of repainting, adding awnings, and updating signage to a comprehensive rehabilitation that provides an entirely new profile for a center. Either approach is valid, depending on the goals to be achieved and the market potential for recouping the investment.

In the transformation of Bayshore Mall in Glendale, Wisconsin, into Bayshore Town Center, a portion of the existing enclosed center was maintained and the overall density of the site maximized by adding a vertical open-air town center component. Offices and apartments are up to six stories above retail, and some stores have two levels. Overall site capacity doubled.

If the buildings are structurally sound, it may be possible to construct new facades around them, thus avoiding demolition and rebuilding and significantly reducing rehabilitation costs. Constructing new facades around the existing structures also makes it easier for tenants to remain in operation during rehabilitation. Opportunities to reduce the visual impact of an older strip center’s length should be examined when rehabilitating the center’s facade. Vertical design details (such as clock towers) can provide visual diversity and minimize the effect of the center’s horizontal form.

One way to update the physical appearance of a shopping center is to create a memorable architectural theme by creating a visual focus or landmark through towers, a dramatic entry, or an identification sign. A center can be given a skyline through the use of architectural detailing. Better-located, larger, and more visible signage for tenants often improves the appearance of a center at minimal cost. Another way is “rehabilitation by subtraction,” that is, removal of dated design features.

Differentiating anchors or developing a hierarchy between anchor tenants and local shops through design elements can update the center’s appearance. Special oversized entry canopies for anchors, a profile involving raised parapets, or striking colors could be used for identification. Removing bulkheads can increase storefront exposure for smaller, nonanchor shops, and it might be desirable to reduce anchor tenants’ storefronts to allow greater visibility for smaller stores.

Establishing a budget for rehabilitating facades requires considerable experience and comparative data. Budgets can vary significantly, depending on the extent of the work to be done. They can range from about $400 per linear foot ($1,220 per meter) of storefront for a minimal facade rehabilitation to as much as $2,000 per linear foot ($6,600 per meter) for a more extensive redesign. Spending a great deal on renovating the facade of a relatively shallow store is less cost-effective than renovating a narrow storefront for a deeper store for which the costs of renovation can be recouped by greater square footage in the store.

The primary challenges in redeveloping Bayshore Town Center in Glendale, Wisconsin, were to relocate existing tenants and maintain store hours for the enclosed portion of the project during construction, prevent disruption to traffic and existing infrastructure during construction, provide ample parking in a limited development area, and adhere to the traditional demands of retail uses in buildings with office and residential above retail. The tenant mix now includes Trader Joe’s, Brooks Brothers, Kohls, H&M, and Boston Store. The town center includes 12 new-to-the-market retailers and restaurants; Cameron’s Steak-house at Bayshore is the first one in Wisconsin.

Bayshore Town Center includes 1.2 million square feet (111,500 square meters) of retail, restaurant, and entertainment space as well as 200,000 square feet (18,600 square meters) of office space and more than 100 rental housing units and condominiums on 45 acres (18 hectares). Before construction of the original shopping center in 1954 and the enclosed mall in the early 1970s, the site was a quarry and a landfill, requiring remediation measures, some of which did not become apparent until construction had started.

Because lighting is such an important factor in the center’s overall appearance, security, and energy consumption, both exterior and interior lighting systems should be carefully inspected and evaluated. Recent innovations in lighting technology have brought better aesthetics along with greater energy- and cost-efficiency. Inexpensive sodium vapor lighting is commonly used in parking lots and other exterior common areas of older retail centers, even though it has certain well-known negative attributes. This type of lighting can now be avoided, however, with the advent of cost-effective “white” lighting that renders colors well and avoids sodium lighting’s eerie and menacing effect. If a center is more than 20 years old, chances are the lighting is outdated and should be upgraded to current standards. The design of light standards must be compatible with the center’s overall design.

As part of the renovation of Wykagyl Shopping Center in New Rochelle, New York, signage was changed to match the new building design and to increase visibility from the road. The marquee is now 20 feet (6 meters) tall, compared with the previous sign, which was four feet (1.2 meters) tall.

Lighting interior common areas is an art and should be carefully coordinated with the center’s overall hierarchy of lighting. It must be sufficient to give the shopping environment an engaging and safe appearance without any glare, but it must also create an intimate atmosphere that highlights individual shop windows and their merchandise. Special consideration must be given to the lighting of mall entrances, signs, architectural features and landmarks, and areas of pedestrian circulation. Interior plants, particularly tropical plants, may require special lighting. Lighting can also be used for purely aesthetic reasons and to attract shoppers to the center at night. In a specialty or entertainment center where themed lighting may be used; however, care must be taken to balance aesthetics with the need for adequate illumination. Because interior lighting should provide a pleasant, natural effect, opportunities to increase natural lighting through skylights and clerestories should be considered.

Because coordinated signage is an essential component of a center’s design, many rehabilitation projects require all signs to be replaced. New signage must be compatible with the overall image projected. Although signage needs to be large enough to convey information from appropriate distances, it must not be so large that it overpowers the design of the buildings. Signs vary depending on whether they are meant to be read from streets or highways adjacent to the center, the parking area, or storefronts. And although graphics should be coordinated, they must strike a balance among the envisioned aesthetic concept, the need for interesting and diverse styles, colors, and designs, and adequate identification for tenants. Retailers are concerned with maintaining their own identities, which must be taken into consideration. In all cases, signage is critical to retailers’ visibility and ultimately their ability to achieve sales. Although design and look are important, the most important function of tenants’ signs is to maximize their traffic.

The design of the parking lot can be a critical factor in the success of a rehabilitation or expansion project. Parking must be convenient, plentiful, and safe. In considering the possibilities for modifying the existing parking area, a developer should analyze ease of ingress and egress, conflicts between pedestrians and vehicles, and the overall configuration and appearance of the parking area.

Fourth Street Live! in Louisville, Kentucky, is a classic example of retail space and entertainment that jump-started a moribund downtown. From the 1970s through the 1990s, Louisville’s downtown commercial and entertainment district grew only more desolate. Then in 2000, the city bought the ailing Louisville Galleria, a suburban-style mall on Fourth Street, and sold it to Baltimore-based developer The Cordish Company for $1. With the city contributing $13 million in public infrastructure improvements and the state’s tourism tax credit program supplying Cordish with up to $11.5 million over ten years, the developer opened the $75 million Fourth Street Live! in May 2004. Designed by New York City-based Beyer Blinder Belle, the project retained parts of the old mall’s roof but reopened Fourth Street to vehicular traffic. Its mix of national chains and local tenants, including a Hard Rock Cafe and other restaurants, Lucky Strike Lanes, and Borders, as well as free live events, drew more than 4.2 million visitors in the project’s first year. A number of other entertainment, residential, and commercial projects are now planned in the area.

Source: Ron Nyren, “ Public/Private Prosperity,” Urban Land, July 2006, pp. 36–40.

Vehicular access to the center often can be improved and congestion minimized on adjacent roadways by redesigning entrances so that they penetrate farther into the site and provide stacking space in the parking area. Deeper entrances also facilitate the use of traffic counters.

Redesigning a shopping center parking lot may also present an opportunity to create more efficient links with neighboring developments. In too many older commercial areas, movement from one shopping center to another requires exiting onto an arterial road rather than traversing a linked parking area. This design creates unnecessary traffic congestion, inconvenience for shoppers, and lost sales because shoppers may be unwilling to try to figure out the traffic maze between centers.

Changing the configuration and appearance of the existing parking lot may also be necessary. In most older centers, parking lots need to be restriped and/ or repaved, offering the chance to change the size of stalls, angles, and widths of bays to use the parking area more efficiently.

Another consideration is whether to expand parking by means of structured or underground garages. When a large expansion is considered and additional land is too expensive or unavailable, structured parking may be the appropriate option. It is also expensive, however, typically costing about $15,000 per above-ground stall and $30,000 per below-ground stall. Thus, the feasibility of adding structured parking must be carefully considered as part of the process to determine whether the proposed expansion makes economic sense.

The large building footprint of a former Sears in Washington, D.C., built in 1941, now accommodates two big boxes, a hardware store, and a specialty comic bookstore. Best Buy and the Container Store, two retailers previously found only in the District’s suburbs, have reinvigorated the area. Parking is below ground for retail customers and on the roof for residents of the condominiums constructed above the retail. Both parking areas were part of the original Sears construction. The retail and residential phases were separated and structured as two condominium units for legal and financial reasons.

Like all other elements of the shopping center, a parking garage should be designed to enhance the center’s overall look. Safety is a major issue, and large, multistory parking garages should be equipped with roving security guards and/or electronic monitors. Good lighting in parking lots is crucial for customers’ and employees’ safety and security.

The need for additional parking with the inclusion of nonretail uses may be addressed, at least in part, by shared parking (see Chapter 4 for more discussion on shared parking, parking structures, and parking standards).

In the rehabilitation of an existing center, improving the landscaping may range from a simple refurbishment of existing landscaping to its total replacement. Plants must be carefully selected and placed to soften the center’s appearance while not blocking views of signage and storefronts. Landscaping must also allow adequate sight distances in parking areas and at vehicular entrances and exits. Plantings, both exterior and interior, should provide as much permanent, year-round greenery as possible and should be highlighted with color from seasonal flowering plants. Indigenous plants are preferred for exterior landscaping, because they are most likely to withstand local climatic extremes and cost less to maintain. They also add to the local character and authenticity of the shopping environment. Plants should be chosen for the drama they impart to the center’s overall appearance, the cost of installation and maintenance, and the need for special lighting or temperatures.

Determining the feasibility of repositioning a shopping center involves a review of existing leases to determine whether they permit changes in the common areas. Pictured: Waterside at Marina del Rey, Marina del Rey, California.

Benches, planters, and trash receptacles should be selected for their design and durability. Furniture in an older center usually needs to be replaced, as it most likely is worn and its design out of date. Although the cost of new furniture is generally small compared with the project’s total cost, the effect of furniture on the center’s overall appearance is significant.

Renovation and expansion of any older center generally involves more than physical changes to the center. The rehabilitation must be coordinated carefully with tenants. And because it must be consistent with the new image and identity being created for the center, the tenant mix must likely be changed or upgraded.

Successful rehabilitation requires the enthusiastic support and cooperation of tenants, which will depend on the developer’s frequent communication and consultation with them. The developer should not announce the rehabilitation to tenants without first thoroughly reviewing and analyzing the existing mix and the status of all leases to locate possible obstacles to the rehabilitation.

Following this tenant-by-tenant analysis, the developer will be in a position to inform tenants of impending rehabilitation by meeting with them to review the rationale for the renovation, the planned architectural design, changes to signage, the construction schedule, the period of time that tenants will be without identifying signage, and the steps that will be taken to minimize the inconvenience to tenants and shoppers. If some tenants are expected to move to a new position in the mall permanently or temporarily while their spaces are being redeveloped, the terms must be negotiated privately with the affected tenants. Adjustments to rent during the disruption will likely be required, and some desirable tenants may choose to leave the center during reconstruction. These realities need to be factored into the economic equation before renovation is undertaken.

In summer 2002, the former Lamont’s was demolished and construction of a new 144,000-square-foot (13,400-square-meter) Nordstrom began. Renovation inside the mall continued apace and was completed by the time the new Nordstrom opened in September 2003. With the old Nordstrom store vacated, the site was freed for the development of the Village, and in 2003 construction began on both the Terraces and the Village, at the southeast and northwest sides of the mall, respectively. At the same time, construction began on two new parking decks, one joined to the new Nordstrom with a skywalk and another adjacent to the Terraces. The existing mall continued to operate, accessed through store entrances to the north and east and through the new Nordstrom store.

The first of the expansion areas, the Terraces, opened to the public in spring 2004. The grand opening of the Village followed in November of that year; a new 16-screen Loew’s entertainment cineplex, seating 3,800 in stadium-style format, opened in spring 2005.

The project was complicated — but not delayed — by two underground conditions. First, a natural-gas pipeline runs beneath the site of the Terraces. Rather than relocate the pipeline far beyond the boundaries of the site, GGP opted to alter the original plan for large trees and tall lampposts in the area and leave the underground line in place. The landscape is enriched with a mix of hardscape, ground cover, and shrubs. Second, the discovery of loose fill soils beneath the pads where new construction was to be located meant that new pilings had to be engineered and placed before foundations could be built.

In the Terraces, a basalt stone and water sculpture by artist John Hoge also provides seating on the polished surfaces.

Although construction at Alderwood was phased to allow the mall to continue to operate with minimum disruption, management and marketing initiatives were combined in a concerted effort to keep customers coming and to build anticipation for the opening of new stores. Working with a local public relations firm, GGP formed a strategy for gradually releasing information to the public about expansion plans. One phase at a time, the list of new tenants and description of buildout was made public, thereby keeping the public focused on changes at the mall and whetting curiosity about future construction.

The company and consultant also designed a customer education and advertising campaign for mall visitors. Flyers describing upcoming construction plans were placed at strategic locations in the mall. Four- by eight-foot (1.2- by 2.4-meter) signs announced the addition of each new major tenant, complete with an architectural rendering of the new store.

A full month of events attended the grand opening of Alderwood. Beginning with radio announcements in late September 2004 and a media tour and slate of invitational events for tenants and project team members in late October, the unfolding of the new mall culminated in a grand opening on November 4. Opening events through the first weekend included product demonstrations by retailers and performances by school groups. Music ensembles, from steel drums to chamber strings, were scheduled for performances in the new outdoor areas. The first 5,000 visitors received totes with free merchandise from tenants.

The opening campaign continued with advertising on transit boards, in local newspapers, and in targeted direct mail. A local marketing firm was hired to distribute 50,000 “java jackets” (coffee cup sleeves) to neighborhood coffee stands. Grand opening events and internal promotions, such as a $1,000 shopping spree, continued through December 2004.

The number of visitors in the opening days exceeded the most optimistic projections. On a Thursday in early November, city fire officials estimated attendance the first day at 20,000, around ten times the average for the day. The following weekend, more than 100,000 came, and the crowds have been steady ever since.

An informal survey taken by GGP over the four-day opening period supports the goal of recapturing a share of the upscale market. For 18 percent of respondents, it was the first visit in more than three months. Eighty-five percent of respondents purchased something, and those with household incomes greater than $100,000 spent the highest daily average—$213. Doubled sales at the new Nordstrom store, which opened in fall 2003, confirm the return of the upscale market to Alderwood, and sales data for other key retailers support this assumption.

The Village opened 85 percent occupied and was 95 percent occupied by the first quarter of 2005, a rate equal to the occupancy of the mall before construction in 1999. The project is on track for a projected pro forma return in the low double digits.

GGP expects to recoup development costs in the form of higher rents during lease rollovers between 2004 and 2009. Annual rents now stand at $45.00 to $60.00 per square foot ($485 to $645 per square meter), with the rents in the two new additions in the upper range. Overall, these rents represent an increase of 10 to 20 percent over the existing center.

The developer also needs to let tenants know what is expected of them during and after renovation with regard to increased CAM and operation costs, the removal of old signs and acquisition of new ones, and similar items. Most important, the developer must convince tenants at this meeting that the renovation is in their best interests by reviewing with them the concept for the renovated center and the advantages they can expect as a result of the reconstruction. Tenants must be reassured and convinced that sales lost during reconstruction (if any) and their increased operating costs following rehabilitation will be more than offset by a greater number of shoppers and higher sales volumes.

After this initial meeting, the developer is in a position to renegotiate leases with individual tenants, keeping in mind which tenants it must retain for successful rehabilitation and that if any tenant is treated harshly, word may spread to other potential tenants. Although lease renegotiations vary from tenant to tenant, the most likely demands from tenants are 1) a contribution or construction allowance from the developer for leasehold improvements, which may include a new storefront and signage, 2) an extended primary term in which to amortize interior store improvements and additional renewal options, 3) a right to terminate the lease early if sales after the rehabilitation do not reach a certain level, 4) the right of first refusal over adjoining space, or 5) the relocation of its space to a more desirable spot. To pay for redevelopment, the developer may seek a commitment from tenants to spend a fixed minimum amount on new signage or new leasehold improvements, an increase in rent, an extension of the lease terms for credit tenants (which can be a requirement of the lender financing the rehabilitation), increased CAM expenses, modification of use clauses and tenant exclusive provisions, and a commitment by key tenants to expand when space is available. What lease concessions each party receives from the other depends on the value of the rehabilitation to the tenant, the profitability of the location, and many other factors.

Rehabilitation or expansion should be carefully planned and scheduled to allow the center to remain fully operational during construction. Interference with traffic carrying shoppers must be minimized to avoid the loss of sales revenue and to protect against potential liability. Entrances and exits to the center (both vehicular and pedestrian) should not be blocked during construction, and it is essential that the site be kept as clean as possible (with daily cleanups by the general contractor). Arrangements should also be made for temporary services needed to provide a convenient, safe atmosphere (temporary lighting, warning signs, barricades, security guards, and so forth). Building materials should not be delivered during peak shopping hours. And construction generally should not occur during the peak retail season; ideally, construction should start after Easter and be completed before Thanksgiving.

Finally, it is imperative that the developer explain the objectives for rehabilitation and expansion to all members of the development team. Rapport must be established among members of the team, and they must agree on the project’s proposed schedule and meet the required deadlines. A tenant coordinator is a key member of the team and should be on board before and during construction to assist tenants.

A complete promotional campaign should be developed for the project consisting of preconstruction announcements, promotion during the renovation, promotion for the grand reopening, and the grand reopening itself. A well-executed promotional campaign, capitalizing on the excitement of the renovation, can actually increase sales activity during construction. When renegotiating leases, the developer/owner should make certain that an assessment for the grand reopening is included in all new leases.

Outdoor shopping is a magnet for upscale consumers—even in cool, rainy climates. Based on solid market research with local consumers and the success of nationwide models, Alderwood joins proven open-air regional projects such as Redmond Town Center and Seattle’s University Place.

Open-air additions can be successfully combined with an existing enclosed mall. With strategic openings in the traditional circulation plan, additions can spill out into parking areas that surround a shopping mall. Independent parking structures can be strategically integrated with the plan as an urban element. Canopies and roof overhangs in outdoor areas add shelter and human scale to common areas.

A plan of phased development and openings, when combined with a complete communications plan that includes on-site signage, mailings, advertising, and special events, is effective in building and sustaining a new customer base. Together, they succeeded in setting expectations and creating enthusiasm at Alderwood. Despite the continuing recession and ongoing construction, total sales for the mall rose 4 percent each calendar year during construction, ending with 8 percent in 2004.

Strategic investments in materials, special public features, and artwork pay off in better ambience and increased market share. Regional character and an individual palette of features and forms are effective in attracting upscale consumers.

In a healthy market, a major regional shopping mall can coexist with a downtown commercial core. The growing city of Lynnwood has based a major planning effort on the assumption that a thriving and expanding Alderwood will contribute to the city’s overall development. The city welcomes the enhanced tax base of the expanded mall and expects to attract dense development of office and multifamily residential projects. A convention center project has been strategically located to bridge the historic gap between town center and mall.

Existing underground conditions may not support new construction, even on recently developed land. At Alderwood, deeper and more complete soil core samples might have revealed the insufficiency of supporting soils. As it developed, the necessity to support pads with new pilings threatened to delay the construction schedule substantially. Moreover, insufficient communication with a private natural gas company before construction meant that design proceeded on the false assumption that the pipeline would be moved, and the situation had to be corrected late in the design process.

Renovation of a shopping center is a complex undertaking. Although the rewards can be significant, numerous problems can arise. Being aware of them can help the developer avoid, or at least plan for, them. The following list describes major problems that can arise during the course of rehabilitation or expansion:

Notes

1 Excluding parking structure.

2 Excluding major tenants.

3 When outdoor additions were completed.

The Waterside at Marina del Rey is a complete reinvention of a shopping center in Marina del Rey, California.

As mentioned, the entire analysis of the viability of any redevelopment comes down to tenants. The goal of the owner in executing any type of redevelopment is to combine a synergistic mix of new and existing tenants with high-sales performance tenants (who are thus able to pay higher rents) with a physical structure and common areas that draw customers (who will generate strong retail sales). Although physical enhancements can help encourage sales, they are not ends in themselves. Strong sales are the test of retailers’ success. An owner who can successfully weave together the many components of a redevelopment described in this chapter to achieve strong tenant sales is surely on the road to financial success by keeping his shopping center vibrant in an industry that is constantly changing.

1. ULI-the Urban Land Institute and ICSC-the International Council of Shopping Centers, Dollars & Cents of Shopping Centers®/The SCORE®, published every two years.

2. Ibid.