Chapter 5

Human-Made Hazards

Terrorism, Civil Unrest, and Technological Hazards

What You’ll Learn

• Categories of human-made hazards

• Types of terrorist acts and tactics

• The likelihood of terrorist attacks compared to other hazard threats

• Ways that civil unrest can cause disorder and disruption

• Common hazardous materials

• Ways in which hazardous materials can affect humans

• The emotional consequences of human-made hazards

• Notable human-made events in U.S. history

Goals and Outcomes

• Assess the procedures and tools to evaluate the risks of human-made hazards

• Distinguish among human-made hazards in a given situation

• Evaluate a community’s preparedness for a hazard event by using an all-hazards approach

• Identify some of the potential human-made hazards in your community

• Assess the public’s perception of risk from terrorism and technological hazards

5.1 Introduction

A resilient community must deal not only with recurrent natural hazards, but must also take action to protect itself from human-made hazards, including those that are accidental as well as hazards that are intentional in nature. This chapter introduces the various types of human-made hazards, and provides a short list of some of the notable human-made events that have occurred in the United States. The chapter then explores the issue of terrorism, a significant intentional threat to our country. Next, the chapter discusses the role of civil unrest and mass shootings, and outlines various technological accidents, such as hazardous materials releases, nuclear reactor incidents, and oil spills. The chapter concludes with a description of some of the psychological effects these types of hazards may produce as well as ways to make our communities less vulnerable to the impacts of human-made hazards.

5.2 The American Experience

When compared with the number of natural hazards such as hurricanes, wildfires, floods, earthquakes, tornadoes, ice storms, landslides, and other feats of nature that have impacted our communities in the past, the United States has experienced relatively few human-made hazards. We have one of the safest transportation systems in the world, a highly regulated nuclear power industry, and stringent laws that restrict the use of chemicals, toxins, corrosives, and other hazardous materials. Yet accidents still happen. Trains can derail, spilling chemicals over the landscape. Nuclear power plants can experience meltdowns, spreading radioactive materials into surrounding communities. Shipping tankers can sink, leaking oil and petrochemicals into the sea. We call these and other accidental human-made hazards technological hazards. This chapter discusses some of the different types of technological hazards and how they can impact our communities.

This chapter also discusses intentional human-made hazards. This category of human-made hazards includes terrorism, which refers to intentional criminal acts carried out for purposes of intimidation or coercion. This category also includes incidents of civil unrest such as riots; these events are potentially dangerous because they can quickly get out of control, leading to extensive property damage, injuries, and even death.

Much of this chapter is based on information distributed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the FEMA, the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). We also used information from the Global Terrorism Database, a comprehensive collection of information about terrorist attacks and attempted attacks occurring in the United States since 1970 through 2011. The database is maintained by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) which is based at the University of Maryland, and is partially funded by the Science and Technology Directorate of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. You can visit the websites of these and other federal, state and university organizations to learn more about the risk of human-made hazards around the country.

5.2.1 The All-Hazards Approach

Despite the feelings of urgency we may have when we consider the threat of terrorism, along with the dangers of technological accidents and civil unrest, we must be careful to keep in mind the array of natural hazards that we know with certainty will occur in this country. We know that hurricanes will continue to ravage our coasts. We know that tornadoes will cause great damage in the Midwest. We know that communities will be flooded time after time. We know that California and a few other states are ripe for an earthquake. We know without a doubt that these hazards will take place in these regions. In our efforts to reduce the dangers posed by human-made hazards, we must not lose sight of the fact that natural hazards are a certainty. We must take care that resources devoted to homeland security are not diverted from our efforts to reduce the impacts of natural hazards through mitigation and preparedness. Our prioritization process must consider all types of hazards when we develop our risk reduction policies and strategies. This approach to dealing with both natural and human-made hazards simultaneously is known as the all-hazards approach. The all-hazards approach is fully endorsed by FEMA, which encourages all communities to adopt mitigation and emergency operations plans that identify and assess risk from multiple sources.

The following quotation illustrates the importance of continuing the all-hazards approach towards hazards management.

The events of 9/11 created a watershed for the profession of emergency management. In the post-9/11 world, the preoccupation with the threat of terrorism has changed political and administrative priorities. Budget allocations for traditional emergency management programs have been subsumed in the larger allocations for homeland security, often with little assurance of the continuity of traditional programs…The all-hazards approach must be continued. The risks posed by earthquakes in California and by hurricanes along the Gulf Coast are potentially far greater than those posed by terrorists. The risks posed by influenza and other diseases (witness the SARS epidemic) are far greater than those posed by terrorists with anthrax, sarin, or other biological and chemical agents.1

It is clear that natural hazards of all types are more likely to occur in the average American community than a terrorist attack, civil unrest, or a technological accident. That being said, however, the impacts of a humanmade hazard, although unlikely, could be quite far-reaching and cause lingering consequences for a long time. As a case in point, the attacks of September 11, 2001 will continue to affect many sectors of the economy (e.g., the commercial airline industry) for years to come. Those attacks will also likely continue to affect the American psyche for generations.

Each community must rank the importance of natural and human-made hazards based on its own unique characteristics. In some communities, susceptibility to a terrorist attack or technological accident is quite low. These communities will focus mainly on the natural hazards that are common in their region. Other communities, however, will find that their vulnerability to a human-made hazard is much higher, perhaps because they provide an attractive target for a terrorist, or because there are multiple locations or occasions where a technological accident could occur. Either way, each community will need to assess for itself what priority it should place on dealing with humanmade and natural hazards, by assessing the probability of each type of hazard occurring in the community and factoring in the most likely consequences.

5.2.2 Significant Human-Made Events in the United States

Table 5.1 lists a few of the more dramatic events that have occurred in our nation’s history. Measured in sheer numbers, the monetary impact and numbers of deaths and injuries come nowhere close to the amount of damage that has been caused by natural hazards over the years. However, these types of hazards have an emotional component that is distinct from that associated with the aftermath of a natural disaster. As an interesting exercise, try to gauge your feelings when you read the short facts listed here. Are you affected in ways that might differ from your reaction if these were events caused by nature and not by fellow humans?

SELF-CHECK

• Define technological hazards, civil unrest, and all-hazards approach.

• Explain the difference between human-made and natural hazards.

• Give an example of three types of human-made hazards.

5.3 Terrorism

In the United States, the official definition of terrorism as stated in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations is “…the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.”*

TABLE 5.1 Selected Man-Made Hazard Events in the United States

Event |

Location |

Type of Hazard |

Description and Impacts |

Fertilizer Plant Explosion April 17th, 2013 |

West, Texas |

Technological accident |

An explosion occurred at the West Fertilizer Company’s storage and distribution facility 18 miles north of Waco, Texas during an emergency services response to a fire at the facility. The explosion was triggered by ammonium nitrate, and resulted in at least 15 deaths, 160+ injuries, and more than 150 damaged buildings |

Boston Marathon Bombings April 15th, 2013 |

Boston, Massachusetts |

Domestic terrorism |

Two pressure cooker bombs exploded near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, killing 3 and injuring 264 others. Three days later two suspects engaged in a firefight with law enforcement, resulting in additional deaths and an unprecedented 20 block lock down in Watertown, Massachusetts |

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill 2010 |

Gulf of Mexico near Mississippi River Delta |

Technological accident |

BP’s oil rig Deepwater Horizon exploded and sank on April 20th, killing 11 oilmen, and resulting in a record breaking offshore oil spill considered the largest accidental marine oil spill in the world. The total discharge is estimated at 4.9 million barrels of oil, and continues to have serious environmental, health and economic impacts |

Anthrax Attacks October 2001 |

Washington, DC New York City, Boca Raton, Florida |

Terrorism of unknown origin |

Letters containing anthrax mailed to news media offices and 2 U.S. Senators; 5 deaths, 22 infected with long-term illness; shutdown government mail service; dozens of buildings decontaminated at estimated cost of more than $1 billion |

Terrorist Attacks September 11, 2001 |

Department of Defense Headquarters (Pentagon) Washington, DC, World Trade Center, New York City Rural Somerset County near Shanksville, Pennsylvania |

International terrorism |

Series of suicide attacks using hijacked airliners; 2986 deaths, thousands injured; 25 buildings in Manhattan destroyed; 1.5 million tons of debris in New York City; portion of Pentagon damaged; costs of clean-up, rebuilding, and economic losses in billions of dollars; stock markets worldwide fell; airline industry severely impacted; massive insurance claims against airlines and others; impetus for large-scale “War on Terror” |

Olympic Bombing July 27, 1996 |

Olympic Centennial Park, Atlanta, Georgia |

Domestic terrorism |

Politically motivated bomb attack; 1 direct death, 1 fatal heart attack, 111 injured; perpetrator Eric Rudolph captured, also charged with other bombings, and sentenced to life imprisonment |

Oklahoma City Bombing April 19, 1995 |

Murrah Federal Building, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

Domestic terrorism |

Bomb made of fertilizer and other readily available materials detonated in rental truck; 168 deaths, more than 500 injured; perpetrators Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols captured, tried, and sentenced |

World Trade Center Bombing February 26, 1993 |

New York City |

International terrorism |

Van with bomb driven into basement parking garage and remotely detonated; 6 deaths, more than 1000 injured; $300 million property damage |

L.A. Riots (also known as Rodney King Riots) April 29, 1992 |

Los Angeles, California |

Civil unrest/race riot |

Six days of rioting sparked when mostly white jury acquitted 4 police officers accused in videotaped beating of African American motorist Rodney King. Thousands of residents joined in what is described as a race riot, involving mass law breaking, looting, arson, murder. 50–60 deaths; more than 2000 injured; 10,000 arrests; $800 million—$1 billion in property damage |

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill 1989 |

Prince William Sound, Alaska |

Technological accident |

Exxon oil tanker ran aground attributed to negligence of Ship’s captain; 40,000 tons of crude oil spilled into ocean and spread along hundreds of miles of coastline; caused severe environmental damage and deaths of marine and coastal wildlife and plants; effects of spill still evident today; Court ordered Exxon to pay $1 billion in damages used for clean-up and restoration; disaster led to passage of federal Oil Pollution Act; Captain fined and sentenced to community service |

Three-Mile Island Nuclear Accident March 28, 1979 |

Near Middletown, Pennsylvania |

Nuclear power plant accident |

Equipment malfunction, design problems, and worker errors led to partial meltdown of reactor core; small off-site release of radioactivity; no deaths; brought about sweeping changes in response training, engineering, radiation protection; caused U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Agency to tighten regulatory oversight. Today reactor is permanently shutdown and defueled |

White supremacist attack on 16th Street Baptist Church 1963 |

Birmingham, Alabama |

Domestic terrorism/civil unrest/race riot |

Four teenaged African American girls killed in bomb attack of church; 23 injured; riots and fires followed in city; 1 suspect acquitted of murder in 1963, retried in 1977, found guilty, and sentenced to life in prison; 2 more suspects tried in 2000, 1 convicted |

Great Fire of Chicago October 1871 |

Chicago |

Accidental fire |

Small barn fire turned into raging conflagration; 300 dead; 18,000 buildings destroyed; 1/3 of population made homeless; city rebuilt in 2 years |

Terrorists often use threats to create fear among the public, to try to convince citizens that their government is powerless to prevent terrorism, and to get immediate publicity for their cause.

5.3.1 Elements of Terrorism

The term terrorism is interpreted in various ways depending on its context, but there are certain core elements that characterize most acts of terrorism:

• Violence: Terrorism generally involves violence and/or the threat of violence.

• Target: Terrorism usually entails the deliberate and specific selection of civilians as direct targets.

• Objectives: Terrorism usually is an attempt to provoke fear and intimidation in the main target audience, to attract wide publicity, and cause public shock and outrage.

• Motives: Terrorist activities may be intended to achieve political or religious goals; terrorists who act as mercenaries may also be motivated by person gain. Historical grievances, retaliation for past actions, and specific demands such as ransom or policy change may also be motivating factors.

• Perpetrators: War crimes and crimes against humanity are not usually included in the definition of terrorism. Likewise, overt government oppression of its own civilians (e.g., the 2013 chemical attacks against civilians in Syria) is not usually considered terrorism. However, state-sponsored terrorism can involve government support of terrorism carried out in another country.

• Legitimacy: Most definitions of terrorism require that the act be unlawful.

A gang of bank robbers who kill the bank manager, blow up the vault, and escape with the contents would not be considered terrorists. But if the robbers did the same thing with the intent to cause a crisis in public confidence in the banking system and destabilize the economy, then the gang could be considered terrorists. In this case, the motive and long-term consequence are factors that distinguish between the robbers who are seeking personal gain and robbers who are seeking to make a political statement and cause widespread and lingering impacts through their actions.

5.3.2 Types of Terrorism

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) characterizes terrorism as either domestic or international, depending upon the origin, base, and objectives of the terrorist actor or group.

• Domestic terrorism involves groups or individuals whose terrorist activities are directed at elements of our government or population without foreign direction.

• International terrorism involves groups or individuals whose terrorist activities are foreign-based and/or directed by countries or groups outside the United States or whose activities cross international boundaries.

The 1995 bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City was an act of domestic terrorism, whereas the attacks of September 11, 2001, were international.

Within these broad categories, there are many different forms of terrorist activity. In the United States, most terrorist incidents have involved small extremist groups who use terrorism to carry out a specific agenda. There is often overlap between the various motives and methods of these different types of terrorism, and some sorts of terrorism cannot be easily classified into any one group. The following list includes some of the different types of terrorism.

• Nationalist: A type of terrorism that involves actors trying to form an independent state in opposition to an occupying or imperial force. Examples: Lebanese, Palestinian, and Northern Ireland terrorist activities.

• Religious: The use of violence to further what the actors see as a divinely commanded purpose or objective. Examples: Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Islamic, and other world religion terrorist groups, often fanatical in nature.

• Left-wing: Terrorism growing from social movements on the left. Example: Symbionese Liberation Army of the 1970s.

• Right-wing: The use of terrorist tactics to eliminate threats to what is seen as traditional values or politically right-wing power structures. Examples: Neo-Nazi, white supremacist, anticommunist groups.

• State: Can include terrorist activities carried out, subsidized, or sanctioned by a national government or its proxy.

• Racist: Terrorism related to issues of race or ethnicity; may be carried out by racist, xenophobic, or fascist groups. Examples: Ku Klux Klan, Neo-Nazis, white supremacist groups.

• Narco-Terrorism: Attempts by narcotics traffickers to influence/intimidate government policies, law enforcement, or the justice system.

• Anarchist: Terrorism intended to carry out the goal of anarchist groups or the elimination of all forms of government.

• Political: Terrorism used to influence sociopolitical events, issues, or policies.

• Ecoterrorism: Acts of sabotage, vandalism, property damage, or intimidation in the name of environmental interests; often target large corporations seen as exploiting or otherwise damaging natural resources. Examples: EarthFirst!, Animal Liberation Front, Earth Liberation Front.

5.3.3 Terrorism Tactics and Weapons

Terrorist attacks are conducted through a variety of means. The level of organization, technological expertise, and financial backing of the terrorist group often determines the type of technique used. The nature of the political, social, or religious issue that motivates the attack, as well as the points of weakness in the terrorist’s target also factor into the type of tactic employed. In the United States, the most frequent terrorist technique has been the use of bombs, although chemical or biological contaminants have also been used.

The following tactics and weapons are among those that have been used to carry out acts of terrorism in the United States:

• Conventional bomb

• Improvised explosive device

• Biological agent

• Chemical agent

• Nuclear bomb

• Radiological agent

• Arson/incendiary attack

• Armed attack

• Cyberterrorism

• Agri-terrorism

• Hijacking

• Car bomb

• Suicide bomb

• Kidnapping

• Assassination

• Sabotage

5.3.4 Biological and Chemical Weapons

• Biological agents are infectious organisms or toxins that are used to produce illness or death in people, livestock, and crops.

• Chemical agents are poisonous gases, liquids, or solids that have toxic effect on people, plants, or animals. Some chemical agents are odorless and tasteless, making them difficult to detect.

Biological agents can be dispersed as aerosols or airborne particles, and can be used by terrorists to contaminate food or water supplies. Depending on the type of agent used, contamination can be spread via wind and/or water. Light to moderate winds will disburse biological agents, but high winds can break up aerosol clouds. Infection can also be spread through human or animal contact. Sunlight can destroy many, but not all, forms of bacteria and viruses.

Severity of injuries from chemical agents depends on the type and amount used, as well as the duration of exposure. Air temperature can affect the evaporation of chemical aerosols, and ground temperature can affect evaporation of liquids. Rainfall can dilute and disperse chemical agents but can also spread contamination. Wind can disperse vapors but can also cause the target area to be dynamic.

The effects of biological and chemical agents can be either instantaneous or delayed up to several hours or several days. Some biological agents can pose a threat for years depending upon conditions. Biological and chemical weapons have been used primarily to terrorize unprotected civilian population in other countries, but have not been used on a large scale within the United States.

THE CHANGING FACE OF TERRORISM IN THE UNITED STATES

Before the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York and at the Pentagon, most terrorist incidents in the United States were bombing attacks, involving detonated and undetonated explosive devices, tear gas, and pipe and firebombs. The anthrax events of 2001 were one of the first known widespread incidents of terrorism that did not involve explosives. In these attacks, letters containing anthrax spores were mailed through the U.S. Postal Service, infecting 22 people and leading to five deaths. (Anthrax is a lethal bacterium that can infect both humans and animals, through ingestion, inhalation or direct contact through an open wound in the skin.) In recent years, concern has been growing about potential damages that could be caused by cyber-terrorism—the use of Internet-based attacks, including acts of deliberate, large-scale disruptions of computer networks. In February 2013, President Obama signed an Executive Order on Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity to make critical infrastructure more resilient to cyber-threats.

5.3.5 Impacts of Terrorism

The effects of terrorism can vary significantly from injuries and loss of life to property damage and disruptions in services. Terrorists often seek visible targets where they can avoid detection before or after an attack, such as international airports, large cities, major international events, resorts, and high-profile landmarks.

Terrorist attacks are often carried out with the objective of crippling or destroying government functions and other fundamental elements of society. Targets with widespread impact include attacks on transportation infrastructure, communications networks, banking and financial sectors, the electrical power grid, the shipping industry, public water supplies, the food industry, and multiple government structures and services.

5.3.6 The Role of FEMA

When terrorism strikes, communities can receive assistance from state and federal agencies operating within the existing Integrated Emergency Management Systems (IEMSs). FEMA is the lead federal agency for supporting state and local responses to the consequences of terrorist attacks.

FEMA’s role in managing terrorism includes both antiterrorism and counterterrorism activities.

• Antiterrorism refers to defensive measures used to reduce the vulnerability of people and property to terrorist acts.

• Counterterrorism includes offensive measure taken to prevent, deter, and respond to terrorism.

The Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) is a congressionally ratified organization that provides form and structure to interstate mutual aid. Through EMAC, a disaster-impacted state can request and receive assistance from other member states quickly and efficiently.*

PUTTING TERRORISM IN THE UNITED STATES INTO PERSPECTIVE

The National Consortium for the START maintains a comprehensive, searchable, open-source database—the Global Terrorism Database (GTD)—that contains information on all terrorist events around the world from 1970 through 2011.* Findings excerpted from a report generated by START in December 20122 provide some general context about the history of terrorist attacks in the United States and may help put the risk of terrorism into perspective. This perspective is essential to the emergency management professional who must allocate limited resources and manpower to mitigate and prepare for all threats that face his or her local community. Consider the following key points that are based in part on START’s terrorism database report:*

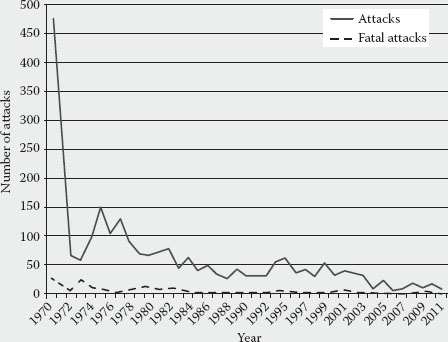

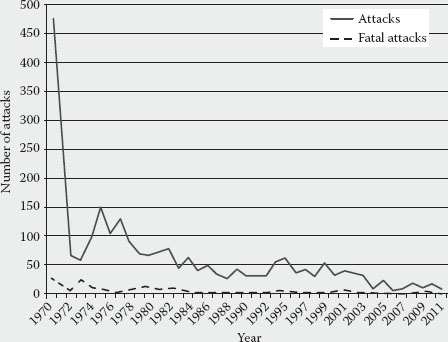

FIGURE 5.1 Total and fatal terrorist attacks in the United States by year 1970–2011.

Point #1: There have been 2608 total attacks and 226 fatal attacks in the United States between 1970 and 2011. However, as shown in Figure 5.1, terrorist attacks and attempted attacks have become less frequent since the 1970s. The attacks of September 11, 2001 were a huge exception in the general trend.

The Global Terrorism Database takes a very comprehensive view of terrorism. It includes both large-scale attacks such as September 11 and the Oklahoma City bombing, along with smaller events that target fewer numbers of people, such as the murder of abortion-clinic doctors, the shooting of the Holocaust Museum guard in 2009, and instances of the Earth Liberation Front setting fire to SUV dealerships.

Point #2: Law enforcement officials appear to be getting better at thwarting terrorist attacks—but they can’t stop all of them.

Although the GTD does not include plots, conspiracies, or hoaxes, the database does include attacks that were attempted but ultimately unsuccessful. The minimum threshold for inclusion of unsuccessful attacks in this sense is that the perpetrators have taken action toward carrying out the attack. In other words, they were “out the door” intending to imminently attack their target. The May 2010 attempted vehicle bombing in Times Square is an example of a serious but unsuccessful attack.

Point #3: Nearly every region of the United States has been hit by some form of terrorist attack since 1970.

When we look at the breakdown of the states that have seen the most attacks and fatalities, New York and Virginia rise to the top in terms of fatalities—primarily because of the September 11 attacks (Pennsylvania also ranks high in terms of fatal attacks because of flight 93 on 9/11). Oklahoma follows these states in number of fatalities, mainly because 168 people died in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing of the Murrah Federal Building.

Florida ranks high on the list in number of attacks because of facility attacks (primarily arson) carried out by the Earth Liberation Front and the Animal Liberation Front, although neither of these organizations are intent on killing people.

Point #4: The types of organized groups that carry out terrorist attacks are very diverse, both in terms of their motives and targets (Table 5.2).

“These organizations are quite diverse,” the START report notes. For instance, the Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) incident was the suicide attack attempted by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab (popularly known as the “Underwear Bomber”) to blow up Northwest Airlines Flight 253 on Christmas Day, 2009, while the Minutemen American Defense, an anti-immigration militia group, targeted a Mexican–American family, and the Justice Department (an animal rights group, not the federal agency by the same name) sent razor blades in envelopes to researchers conducting experiments on animals.

TABLE 5.2 Groups Responsible for Most Terrorist Attacks in the United States, 2001–2011

Rank |

Organization |

Number of Attacks |

Number of Fatalities |

1 |

Earth Liberation Front (ELF) |

50 |

0 |

2 |

Animal Liberation Front (ALF) |

34 |

0 |

3 |

Al-Qa’ida |

4 |

2996 |

4 |

Coalition to Save the Preserves (CSP) |

2 |

0 |

4 |

Revolutionary Cells-Animal Liberation Brigade |

2 |

0 |

5 |

Al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) |

1 |

0 |

5 |

Ku Klux Klan |

1 |

0 |

5 |

Minutemen American Defense |

1 |

2 |

5 |

Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) |

1 |

0 |

5 |

The “Justice Department” |

1 |

0 |

Point #5: Bombings have long been the tactic of choice for terrorists in the United States (51.53% of all attacks). The second-most favored tactic is facility attack (30.55%); armed assault, assassination, hostage taking/kidnapping, unarmed assault, and hijacking account for the remaining number of tactics used.

Point #6: North America suffers far fewer terrorist attacks than most other parts of the world. Ranked by incident count, the Middle East and North Africa top the chart for most terrorist attacks, followed by South America, South Asia, Western Europe, and other regions.

Point #7: Your odds of dying in a terrorist attack are still much lower than dying from just about anything else. Ranking death in America by the odds of dying in a given year under selected circumstances, you are most likely to die of heart disease (467 to one) and least likely to die of asteroid impact (75 million to one). In between, you may die from an accident (1656/1), assault by firearm (24,974/1), or lightning (10,495,684/1). The odds of an American being killed in a terrorist attack is about 1 in 20 million.*

That said, terrorist attacks obviously loom much larger in our collective consciousness—not least because they’re designed to horrify. So, understandably, they get much more attention.3

* You can search the Global Terrorism Database from the START website at http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/. At the time of this writing, the GTD contained information on terrorist incidents from 1970 to 2011, with annual updates planned.

* The discussion regarding the likelihood of a terrorist attack in the US is based on a blog posting by Brad Plumer, Eight facts about terrorism in the United States. The Washington Post WONKBLOG. April 16, 2013. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/04/16/eight-facts-about-terrorism-in-the-united-states/.

* Danger of death! How you are unlikely to die. February 14, 2013, 18:27 by Economist.com. http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2013/02/daily-chart-7?fsrc=scn/tw/te/dc/dangerofdeath.

SELF-CHECK

• Define terrorism, domestic terrorism, international terrorism, chemical agents, biological agents, antiterrorism, and counterterrorism.

• Name six elements common to most acts of terrorism.

• List some of the different types of terrorism.

• Compare biological agents and chemical agents.

5.4 Civil Unrest

Civil unrest is a term used to describe a variety of events that can cause disorder and disruption to the normal functions of a community. Incidents of civil unrest can involve violence, looting, vandalism, sabotage, destruction of property, threats, and other forms of antisocial behavior, but just as often, demonstrations of popular discontent are well-organized and carried out in a calm, lawful manner. Civil unrest can occur as the result of a planned event (for example, a parade or rally that unexpectedly changes character), or when witnesses or bystanders react or stage a counter-protest of their own. Civil unrest can also occur as a spontaneous reaction to an external catalyst.

PROTESTING THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION

On November 30, 1999, a crowd of 40,000 took to the streets of Seattle, Washington to protest meetings of the World Trade Organization. Many of the protestors intended to conduct nonviolent methods of protest, but splinter groups engaged in property destruction and vandalism. Protestors chained themselves together, as police fired tear gas, rubber bullets, and pepper spray into the crowd. The mayor of Seattle imposed a curfew and created a 50-block “No-Protest Zone.” The protests caused $2–$3 million in property damage, city merchants lost approximately $9–$18 million in sales, and further losses in the tourism and travel industries were reported for months following the incident.

5.4.1 Public Order Events on College and University Campuses

College and university campuses have long been a focal point for all forms of protests, demonstrations, and public order events. From the “Occupy Movement” to marches against animal research, campuses can be a hotbed for activism. Campus emergency managers face a unique environment on a college campus. A large community of young and often idealistic students who are ready to publicly advocate for topical issues, an underlying philosophy of academic freedom, and the general atmosphere of tolerance and inclusiveness form the foundation for frequent demonstrations at many university campuses across the country.

Because of the different characteristics of colleges and universities, planning for security and incident response should be made based on a threat assessment of the campus. The primary challenge for emergency managers and law enforcement is to maintain control in order to protect life and safety of both protestors and bystanders, while at the same time respect and protect the constitutional rights of freedom of speech and assembly. For example, establishing a “Free Speech Zone” within the vicinity of a demonstration or protest can help diffuse tensions of counter protestors, agitators, or groups from outside the campus community.

An incident that is often cited as an example of over-reach on the part of law enforcement during a campus protest is the Kent State shooting that occurred on May 4, 1970. Also referred to as the Kent State Massacre, four students were killed and nine were injured by National Guardsmen who had been dispatched to the Kent State University campus in response to demonstrations carried out by students protesting the Cambodia incursion during the Vietnam War. Following the killings, unrest across the country escalated to the point that nearly 500 colleges were shutdown or disrupted by intense and sometimes volatile protests.

5.4.2 Race Riots

A race riot is an outbreak of violent civil unrest in which issues of race are a key factor. Such riots often involve tensions between racial or ethnic groups and law enforcement agents who are seen as unfairly targeting these minorities. Socioeconomic conditions are an underlying cause of many race riots. Racial profiling, police brutality, institutional racism, racially determined policies and politics, and issues of racial and ethnic identity are often common factors among race riots. Urban renewal (such as the construction or removal of publicly subsidized housing, slum or ghetto improvements, and the elimination of blight) has also been cited as a contributing cause of race riots in cities across the country.

Race riots in the United States have included attacks on Irish Catholics and other immigrants in the nineteenth century, massacres of black people in the period following Reconstruction, and uprisings in African–American communities such as the 1968 riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. The Rodney King riot in Los Angeles was the largest riot seen in the United States since the civil rights era of the 1960s. The LA riot lasted for 4 days in 1992 following the acquittal of white police officers who had been charged with police brutality which was caught on videotape.

5.5 Mass Shootings

Generally, mass shootings involve the death of four or more victims; the total death count may or may not include the perpetrator. These shootings are typically carried out by a lone gunman who is not acting as part of an organization or identified group. Mass shootings are usually distinguished from murders related to gang activity. Between 1982 and 2013 there were at least 62 mass shootings across the country, with killings in 30 states from Massachusetts to Hawaii. Of the 143 guns possessed by the killers, more than three quarters were obtained legally. More than half of the cases involved school or workplace shootings; the remaining cases took place in public locations including shopping malls, restaurants, and religious and government buildings. Forty-four of the killers were white males. Only one was a woman. The average age of the killers was 35, though the youngest among them was a mere 11 years old (in Jonesboro, Arkansas, in 1998). A majority of the shooters were determined to be mentally disturbed.4

5.5.1 Mass Shooting Patterns

Despite these gruesome details, statistically the incidence of mass shootings has not risen significantly in the United States over the past three decades,5 although media attention and increased coverage of shooting events that involve multiple victims may make us feel as though we are in an “epidemic” of mass killings. When the events are tallied, we see that there have been short-term spikes where several shootings are clustered close together in time. For example, in the 1980s we had a flurry of shootings by postal workers, and the 1990s included a half dozen schoolyard massacres.4,5 Copycatting—the threat or attempt to carry out a similar attack—may explain some of these clusters. However, while research on mass murder has indicated the potential for a contagion effect in which the actions of some perpetrators may be triggered by reports of other events, the research cannot be substantiated due to the lack of experimental controls.

5.5.2 Notable Mass Shooting Events

Mass shootings are a serious issue for law enforcement and emergency managers in large cities, small towns, and on college campuses throughout the United States. Some of the most highly publicized mass shootings include the following:

• Sandy Hook Elementary School Shooting: On December 14, 2012, 20-year-old Adam Lanza fatally shot 20 children and six adult staff members in a mass murder at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. Before driving to the school, Lanza shot and killed his mother at their Newtown home. As first responders arrived, he committed suicide.

• Aurora Theater Shooting: On July 20, 2012, a mass shooting occurred in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, during a midnight screening of the film The Dark Knight Rises. A gunman, dressed in tactical clothing, set off tear gas grenades and shot into the audience with multiple firearms, killing 12 people and injuring 70 others. The sole suspect, James Eagan Holmes, was arrested outside the cinema minutes later.

• Virginia Tech Shooting: April 16, 2007, on the campus of in Blacksburg, Virginia, a student shot and killed 32 people and wounded 17 others in two separate attacks, approximately 2 hours apart, before committing suicide (another six people were injured escaping from classroom windows). The shooter had previously been diagnosed with a severe anxiety disorder.

• Columbine School Shooting: April 20, 1999, at Columbine High School in Columbine, Colorado. In addition to shootings, the attack involved a fire bomb to divert firefighters, propane tanks converted to bombs placed in the cafeteria, 99 explosive devices, and bombs rigged in cars. Two senior students, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, murdered a total of 12 students and 1 teacher. They injured 24 additional students, with 3 other people being injured while attempting to escape the school. The pair then committed suicide.

• The Bath School Disaster: Is the historical name of the violent attacks perpetrated by Andrew Kehoe on May 18, 1927 in Bath Township, Michigan, that killed 38 elementary school children and six adults in total, and injured at least 58 other people. Kehoe first killed his wife, fire-bombed his farm and set off a major explosion in the Bath Consolidated School, before committing suicide by detonating a final explosion in his truck.

5.5.3 Lessons Learned

With each mass shooting event, emergency managers have learned more about ways to prepare and respond, and to employ a variety of tactics to stop a shooting rampage in progress. Among the lessons learned, communication alerts about an active shooter on the loose are key to survival of potential targets. For example, during the Virginia Tech shooting, students and others on campus used social media to send messages to one another during the 2-hour ordeal. Following the Columbine event, there was increased attention to issues of high school cliques, subcultures and bullying, in addition to the influence of violent movies and video games in American society. That shooting resulted in an increased emphasis on school security as well as nationwide anti-bullying campaigns. The Sandy Hook shooting stressed the need for training and drills for students and staff to be prepared for all types of emergencies.

While each of these events was carried out in a unique setting with varying numbers of deaths and injuries, the large majority of mass shooting incidents are carried out by a lone gunman who was subsequently determined to be psychotic or otherwise mentally troubled. This emphasizes the need for emergency management, law enforcement and security forces to receive training in how to deal with people who are acting with intent to harm themselves and others and who may behave erratically.

SELF-CHECK

• Define civil unrest, race riot, mass shooting, and copycatting.

• Cite two examples of civil unrest from U.S. history.

• Name four lessons learned in the aftermath of mass shooting events.

5.6 Technological Hazards

From industrial chemicals and nuclear materials to household detergents and air fresheners, hazardous materials are part of the modern world. These materials are used to make our water safe to drink, generate energy, provide fuel for vehicles and machines, increase farm production, simplify household chores, aid in medical care and research, and act as key components in many of the products we use every day. As many as 80,000 products pose physical or health hazards and can be defined as hazardous. Each year, more than 700 new synthetic chemicals are introduced in the United States.* Technological hazard incidents occur when hazardous materials are used, transported, or disposed of improperly, potentially exposing the community to harmful consequences.

5.6.1 Community Impacts from Technological Hazards

Technological hazards can occur at any time without warning. Hazardous materials can enter a community during any stage of the materials’ life cycle, including production, storage, transportation, use, and disposal. Even if hazardous materials are handled safely, they may be of concern if a precipitating event occurs, such as a fire. Hazmat incidents can cause widespread impacts throughout a community, such as power outages, disruptions in communications, and damage to critical infrastructure. In extreme events that involve widespread dispersion of hazardous chemicals through water or air, evacuations of the affected populations may be required. If serious long-term contamination of local groundwater, surface water, or soils occurs, residents may be forced to relocate or even abandon their homes and businesses.

DEEPWATER HORIZON OIL SPILL

From April 20 through July 15, 2010, an estimated 210 million gallons of oil flowed into the Gulf of Mexico following the explosion and sinking of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil rig, which claimed 11 lives. In what is considered the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry, a massive response was undertaken in an attempt to protect beaches, wetlands, estuaries, marine and wildlife habitat, and the Gulf’s fishing and tourism industries. While research studies continue to investigate the environmental, economic and health consequences of the disaster, it is clear that the spill impacted thousands of marine species, resulted in physical and mental health problems for residents along the Gulf Coast, and cost the commercial fishing industry approximately $2.5 billion and the tourism industry approximately $23 billion.

5.6.2 What Makes Hazardous Materials Hazardous?

Hazardous materials are substances that, because of their chemical or toxic nature, pose a potential risk to life or health. Many of the properties of chemicals that make them valuable, such as their ability to kill dangerous organisms in water and pests on crops, pose a hazard to humans and to the environment if the chemicals are mishandled. Hazardous materials come in the form of explosives, flammable and combustible substances, poisons, and radioactive materials, and can cause death, serious injury, cancer, and other long-lasting health effects.

There are many definitions and descriptive names that are used for the term hazardous materials, each of which depends on the nature of the problem being addressed. The list that follows includes some of the definitions used by federal agencies responsible for regulating hazardous materials.

• Hazardous Materials: The United States DOT uses the term hazardous materials to cover eight separate hazard classes, some of which have subcategories or classifications. The classes include explosives, gases, flammable liquids, flammable solids, oxidizing agents and organic peroxides, toxic and infectious substances, radioactive substances, and corrosive substances. A ninth class covers other regulated materials (ORM).

• Hazardous Substances: The EPA uses the term hazardous substances for the chemicals that, if released in the environment above a certain amount, must be reported, and, depending on the threat to the environment, federal involvement in handling the incident can be authorized.

• Extremely Hazardous Substances: EPA uses the term extremely hazardous substances for the chemicals that must be reported to the appropriate authorities if released above the threshold reporting quantity. Each substance has a threshold reporting quantity.

• Toxic Chemicals: EPA uses the term toxic chemicals for chemicals whose total emissions or releases must be reported annually by owners and operators of certain facilities that manufacture, process, or otherwise use a listed toxic chemical.

• Hazardous Wastes: EPA uses the term hazardous wastes for chemicals regulated under the Resource, Conservation and Recovery Act. Hazardous wastes in transportation are regulated by DOT.

• Hazardous Chemicals: OSHA, within the U.S. Department of Labor uses the term hazardous chemical to denote any chemical that would be a risk to employees if exposed in the work place. Hazardous chemicals cover a broader group of chemicals than the other chemical lists.

• Hazardous Substances: OSHA uses the term hazardous substances in regulations that cover emergency response. Hazardous substances, as used by OSHA, cover every chemical regulated by both DOT and EPA.

5.6.3 Symptoms of Toxic Poisoning

Some of the symptoms that people may exhibit after being exposed to certain hazardous materials include

• Difficulty breathing

• Irritation of the eyes, skin, and throat

• Irritation in the respiratory tract

• Changes in skin color

• Headaches or blurred vision

• Dizziness

• Clumsiness or lack of coordination

• Cramps or diarrhea

• Nausea or vomiting

5.6.4 Sources of Hazardous Materials

Many businesses and facilities throughout the United States use and store hazardous materials. Chemical manufacturers and refineries are among the industries that are well recognized as hazardous materials sites; however, hazardous materials are also present in many other locations in our communities. For example, the food processing industry may have large quantities of hazardous materials such as ammonia in the refrigeration systems of their plants, warehouses, distribution centers, and cargo carriers. Local drinking water systems, sewage treatment plants, and public swimming pools also store chemicals that are used to kill dangerous bacteria in the water, but which can be toxic if handled improperly.

Many retail commercial sites also use, store, and sell chemicals and toxic substances. Hazardous materials can be found in hardware stores, agriculture supply centers, garden shops, and in pest control businesses. Many small operations, including service stations, dry cleaners, and garages, also routinely use hazardous materials in their daily operations. Hospitals, clinics, and research universities store and use a range of biohazard, radioactive, combustible, and flammable materials. In all, varying quantities of hazardous materials are manufactured, used, or stored at an estimated 4.5 million facilities in the United States. In addition, there are approximately 30,000 hazardous materials waste sites in the country.

5.6.5 OSHA Safety Data Sheets

OSHA has set permissible exposure levels of many chemicals for workers who may come in contact with hazardous substances while on the job. In 2012, OSHA issued revised provisions to implement the “Employee right to know” rules. The revised Hazard Communication Standards (HazCom) require that Safety Data Sheets (SDS) (formerly known as Material Safety Data Sheets) be available to employees for potentially harmful substances handled in the workplace. HazCom 2012 requires chemical manufacturers and importers to provide a label that includes a unified product identifier, pictogram, signal word, and hazard statement for each hazard class and category. Precautionary statements must also be provided.

An important component of workplace safety, the SDS provides workers and emergency personnel with procedures for handling or working with that substance in a safe manner and includes information such as physical data (melting point, boiling point, flash point, etc.), toxicity, health effects, first aid, reactivity, storage, disposal, protective equipment, and spill handling procedures. This information can be life-saving to first responders who may be called to the scene of a hazmat incident.

COMMUNICATING HAZARDS WITH PICTOGRAMS

As of June 1, 2015, the Hazard Communication Standard issued by OSHA requires pictograms on labels to alert users of the chemical hazards to which they may be exposed. Each pictogram consists of a symbol on a white background framed within a red border and represents a distinct hazard or combination of hazards, such as health, physical, and environmental. The pictogram on the label is determined by the chemical hazard classification. For example, the Skull and Cross Bones must appear on the most severely toxic chemicals that pose a risk of death or severe health impairment, while the environment symbol appears on chemicals that are acutely hazardous to fish, crustacean, or aquatic plants (see Figure 5.2).*

FIGURE 5.2 OSHA requires pictograms on labels to alert users of the chemical hazards to which they may be exposed.

* To see the pictograms and federal requirements for their use, visit the Occupational Safety and Health Administration website: www.osha.gov.

SELF-CHECK

• Define hazardous materials.

• Explain how a hazardous material becomes a technological hazard.

• List five symptoms of toxic poisoning.

• Name the federal agency that sets safety regulations for workers exposed to chemicals.

• Discuss the various sources of hazardous materials in a typical community.

5.6.6 HazMat Transportation Accidents

Communities and residences located near facilities that handle hazardous materials are considered at higher risk of experiencing a hazmat incident than areas that are further removed. However, no community is completely immune, since hazardous materials are transported regularly over our highways, by water, pipeline and by rail. Over 3.1 billion tons of hazardous materials are shipped annually, and if any of these materials are released during a traffic, train, or pipeline accident they can spread quickly and impact a large area.

The Federal hazardous materials transportation law is the basic statute regulating the transportation of hazardous materials in the United States. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) within the U.S. Department of Transportation is charged with protecting people and the environment from the risks inherent in transportation of hazardous materials by all modes of transportation, including pipelines. The PHMSA issues permits and ensures compliance of the law’s provisions. The PHMSA’s mission also includes preparedness and response, and focuses on training of all hazmat employees involved in transport, along with planning, exercising, and enhancing capabilities (see Figure 5.3).

Communities located on the known transit route of hazardous materials must take extra precautions to be ready to respond quickly in case of an accidental spill or release of chemicals during transportation. Accidents are reported directly to the 24-hour National Response Center which dispatches trained hazmat responders. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Transportation operates a 24-hour Crisis Management Center, and many state level agencies are also on alert for transportation accidents.

FIGURE 5.3 Freight train derailments can pose significant environmental hazards for communities and response workers. HazMat teams were activated to respond to this incident in Lee, Massachusetts in 2010, when a tanker carrying 20,000 gallons of ethanol jumped the tracks. (Photo credit by Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.)

HUMAN ERROR DURING TRANSPORTATION

Human error is the cause of many of the transportation incidents involving the release of hazardous materials. This was the case in the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, where operator error was thought to have contributed to the crash of the oil tanker into a reef in Prince William Sound, Alaska, in 1989. Nearly 11 billion gallons of crude oil spilled into the bay, killing millions of fish and other aquatic animals and contaminating the water and shore of the Bay for years. The Valdez spill is considered as one of the most devastating human-caused environmental disasters, and was the largest ever in U.S. waters until the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in terms of volume released.

5.6.7 Leaks during Storage and Disposal

There are a number of federal and state regulations that must be met for the safe and proper storage of hazardous chemicals and materials. Chemical storage buildings must be designed to contain liquid spills, leaks, vapors, and explosions to minimize risk to workers in the facilities or to the environment. Chemical storage buildings in particular must be designed to prevent the leaking of liquids into the environment. Chemical storage buildings are often constructed with steel grates and sumps in the floor of the building to collect and contain spilled hazardous chemicals. The building might also have partitions to segregate different substances.

Despite the rules and regulations imposed by the EPA, DOT, OSHA, and numerous state agencies, leaks, spills, and other accidental releases from storage facilities do occur. There is the potential for leaks and spills to go undetected for weeks, months, and even years, especially when storage containers are buried underground. Undetected leaks can cause the substances to leach further into the soil or enter groundwater, endangering residents for miles around.

Hazardous waste disposal sites are also heavily regulated by local, state, and federal authorities. Most disposal sites are located in areas removed from human habitation, although problems arise when community growth and development sprawl into areas where hazardous materials have been deposited. Most disposal sites must be lined with materials that are suitable to contain the hazardous wastes deposited there in order to prevent leaching into the surrounding environment. However, many communities have experienced problems with leaking, abandoned, or improperly maintained and monitored sites.

Identifying the location, size and contents of storage and disposal facilities is the first step in preparing for and mitigating the impacts of an accidental or intentional release or spill. Often, however, security concerns require that the location and other identifying features of hazardous materials facilities are not disclosed publicly due to the risk of sabotage or terrorist strike. These concerns make the job of mapping and preparedness training more challenging for the community. These concerns also highlight the importance of an all-hazards approach to emergency management at all levels of government.

DANGERS LURKING AT HOME

Despite the dangers of chemical leaks and accidents during transportation, storage, and disposal, most victims of chemical accidents are injured at home. These incidents usually result from a lack of awareness or carelessness in using flammable or combustible materials. Local poison control centers are set up nationwide to deal with accidental ingestion or spills of many types of hazardous materials; many of the calls received by these centers involve small children who have gained access to improperly stored hazardous materials such as cleaning solutions, antifreeze, and other substances that can be fatal if swallowed or touched.

Hazardous materials can also be released during routine household chores. Residents may not realize that flushing cleaning solutions and other household substances down the toilet or washing them down the sink allows these dangerous elements to enter our environment directly. The simple act of hosing down a driveway can wash oil, gasoline, and other harmful substances into the local storm water and drainage systems, where it flows into our rivers and streams and eventually enters our drinking water supplies.

5.6.8 Nuclear Accidents

Nuclear power plants use the heat generated from nuclear fission in a contained environment to convert water to steam, which powers generators to produce electricity. Nuclear power plants operate in most states in the country and produce roughly 20% of the nation’s power. About 17 million Americans live within 10 miles of an operating nuclear power plant, and nearly 120 million Americans live within 50 miles of a nuclear power plant.

Although the construction and operation of these facilities are closely monitored and regulated by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), accidents are possible. An accident may result in dangerous levels of radiation that could affect the health and safety of nearby residents. Exposure to radiation is caused by the release of radioactive materials from the plant into the environment, characterized by a plume (cloud-like formation) of radioactive gasses and particles. Wind speed, wind direction, precipitation, and the amount of radiation released from the plant are all factors in determining the area that could be affected. The major hazards to people in the vicinity of the plume are radiation exposure to the body from the cloud and particles deposited on the ground, and inhalation or ingestion of radioactive materials. State and local emergency management officials work together year round to coordinate emergency response plans and activities in the event of a radiation release.

5.6.9 Emergency Planning Zones

The electric utilities that are the owner-operators of nuclear power plants are required to develop, update and practice emergency response plans to deal with a potential nuclear power plant incident. The plans define two “emergency planning zones.” One zone covers an area within a 10-mile radius of the plant, where people could be harmed by direct radiation exposure. The second zone covers a broader area, usually up to a 50-mile radius from the plant, where radioactive materials could contaminate water supplies, food crops, and livestock.

Under federal rules, U.S. communities plan and practice for evacuation or other protective action by residents only within the 10-mile zone surrounding a nuclear power plant. However, because a major nuclear accident has not occurred in the United States, the reaction of residents in the 50-mile planning zone is unknown. It is possible that people living beyond the official 10-mile evacuation zone might be so frightened by the prospect of spreading radiation that they would flee on their own, clogging roads and delaying the escape of others. Emergency managers tasked with planning for nuclear accidents may need to take the potential for increased numbers of evacuees into account when developing evacuation routes and procedures.

THREE-MILE ISLAND NUCLEAR REACTOR ACCIDENT

The accident at the Three-Mile Island Unit 2 (TMI-2) nuclear power plant near Middletown, Pennsylvania on March 28, 1979, was the most serious in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant operating history and, until the Chernobyl accident in the Soviet Union in 1986, was considered the worst civilian nuclear accident in the world. Although the incident resulted in no deaths or injuries to plant workers or members of the nearby community, the event did bring about sweeping changes involving emergency response planning, reactor operator training, human factors engineering, radiation protection, and many other areas of nuclear power plant operations. It also caused the U.S. NRC to tighten and heighten its regulatory oversight.

Americans’ sensibility to nuclear plant accidents was heightened by the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear complex in Japan, which was severely damaged by the massive tsunami triggered by an earthquake that occurred off the coast of Japan in 2011. Of the 65 commercial nuclear power plants operating in the United States, several are located in or near seismic zones, and several others are located in coastal areas that are prone to sea level rise, storm surge and flooding. This proximity to known hazard areas requires emergency managers in these communities to use a rigorous approach to calculating the risk and potential impacts of a nuclear power plant accident. For a map and a list of power reactor sites in the United States, visit the Nuclear Regulatory Commission website (www.nrc.gov).

5.6.10 HazMat Releases during Natural Hazard Events

Natural hazard events, including hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and earthquakes, have often triggered technological hazards. Natural hazard events can rupture pipelines, spark fires, dislodge tanks and storage containers, and cause safety measures to malfunction.

The occurrence of a technological hazard during a natural hazard event is often called a secondary hazard, because it occurs as a result of the primary natural event. Sometimes, the release of hazardous materials during a flood or other natural hazard causes more damage to the environment and surrounding community than the original event itself. One of the most striking examples of a secondary hazard caused by a precipitating natural event is the 2011 earthquake that struck Japan, causing a catastrophic tsunami with heights of up to 133 feet. The tsunami resulted in a considerable secondary hazard when a meltdown occurred in one of the reactors of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Thousands of residents were evacuated because of the threat of radiation contamination. These evacuees were combined with the residents that survived the earthquake and tsunami to reach a total of several hundred thousand individuals and families seeking shelter from the multiple disasters.

SELF-CHECK

• Define secondary hazard.

• Explain how hazardous incidents can occur during transportation.

• Describe how emergency planning zones around nuclear power plants are determined.

• Give an example of how a natural hazard could trigger a technological hazard.

5.7 Public Perception of Human-Made Hazards

One of the main differences in dealing with human-made disasters as opposed to natural disasters is that the majority of people have not had a personal experience with a human-made event. Although we are keenly aware of the increase in terrorist activities directed against the United States and have some knowledge of the number of industrial hazards located near population centers, the public’s perception of the actual degree of risk that we face from terrorism and technological accidents varies widely.

There are many factors that affect how members of the public view the possibility and consequences of human-made hazards in their community. Knowledge of these factors is critical to a full understanding about human reaction to hazards; that knowledge is essential in the emergency manager’s all-hazards approach to preparedness and mitigation in their communities.

5.7.1 Media Coverage

The media plays a vital role in shaping our attitude about and perception of terrorism as well as other human-made hazards. We live in an age of near-instant communication. We can mark some of the most dramatic events in our minds because we have seen them on television—sometimes during live coverage—and we are increasingly able to follow events as they occur through Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and other forms of social media. The images that the media chooses to show the public, as well as the news coverage that accompanies those images, directly affect the way we think about human-made hazards. Often, the most startling and graphic images are those that sell the most news, and in a for-profit news industry, we may be subjected to the most graphic images of all. This is not to say that these are not newsworthy images, but we must remember that the public’s knowledge is often limited to what the media choose to broadcast.

5.7.2 Individual Experience

A second element that factors into the public perception of risk involves an individual’s experience with various hazard events. Since the time of the Civil War, relatively few people in the United States have actually lived through a human-made hazard event, either intentional or accidental. This is in huge contrast with natural hazard events, where untold thousands of people have at one time or another personally experienced a flood, earthquake, severe winter storm, tornado, hurricane, or other type of natural hazard. Natural disasters in this country cause fewer deaths or serious injuries than in other parts of the world (although Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was a tragic exception to this national average). But property damage from natural hazards is extremely common, and the costs of disasters from natural hazards have risen dramatically over the past few decades. In contrast, there are many fewer property owners who have been affected by a human-made hazard. Interestingly, this reality does not factor into the perception of risk that many people associate with human-made hazards.

5.7.3 A Range of Strong Responses

Because the United States has a relatively short history of human-made hazards, discussion on this subject may be characterized by elements of uncertainty and even fear. Planners and emergency managers who work with the public must realize that there could be strong personal responses as people try to grapple with the idea of the possibility of a terrorist attack or technological hazard. New issues may arise that do not come up when dealing with natural hazards, such as concerns over security, access to information, and civil liberties.

To gain public support for efforts to mitigate and prepare for humanmade hazards, emergency managers and planners must be prepared to educate officials, citizens, and the private sector about the hazards that may affect the community and about the prevention and mitigation activities that can help address them. A realistic, comprehensive picture of hazard possibilities is essential, without overstating or inflating the risk, nor underestimating or devaluing the possibilities.

5.7.4 Mitigating and Preparing for Human-Made Hazards

We are not powerless in the face of the many human-made hazards that face our communities. We may not be able to prevent all acts of terrorism or technological accidents from happening, but we can make sure that the possibility of an attack or accident is reduced, and we can take steps to reduce losses by protecting people and the built environment. In this way, our approach to human-made hazards is similar to our approach to dealing with natural hazards. A resilient community is one that realizes that many of these events cannot be stopped, but that action can be taken today to prevent a disaster in the future.

The process of mitigating hazards before they become disasters is similar for both natural and human-made events. Whether we are dealing with natural disasters, threats of terrorism, or hazardous materials incidents, we use a four-step process:

Step 1: Identify and organize resources.

Step 2: Conduct a risk or threat assessment and estimate potential losses.

Step 3: Identify mitigation actions that will reduce the effects of the hazards and create a strategy to prioritize them.

Step 4: Implement the actions, evaluate the results, and keep the plan up to date.

This step-by-step process is known as mitigation planning, and we will discuss it at length in later chapters.

SELF-CHECK

• Describe the role of the media today in the public’s perception of human-made disasters.

• Compare the fear factor of a hurricane versus that of a terrorist attack.

• Identify the four steps of a mitigation planning process.

Summary

Although this country has experienced relatively few human-made hazards, we must be prepared to cope with both accidental and intentional humanmade threats. This chapter explains the ways in which natural hazards and human-made hazards differ, but also how emergency managers can approach both effectively. Antiterrorism and counterterrorism activities are at work to reduce the impact of terrorism on our country. The chapter discusses acts of civil unrest, such as riots, demonstrations, and mass shootings in the context of our emergency management system. Hazardous materials are an integral part of life today, but our goal is to minimize their potential to detrimentally impact our communities through careful planning and advanced preparedness training and exercises. Finally, the chapter examines the public’s changing perception of human-made hazards and what can be done to proactively address and manage people’s fears and concerns.

Key Terms

All-hazards approach |

A method for dealing with both natural and human-made hazards. |

Antiterrorism |

Defensive measures used to reduce the vulnerability of people and property to terrorist acts. |

Biological agent |

Infectious organisms or toxins that are used to produce illness or death in people. |

Chemical agent |

Poisonous gases, liquids, or solids that have toxic effects on people, plants, or animals. |

Civil unrest |

Unexpected or planned events that can cause disorder and disruption to a community. |

Copycatting |

A term used when someone threatens or attempts to replicate the actions of a previous perpetrator. |

Counterterrorism |

Offensive measures taken to prevent, deter, and respond to terrorism. |

Domestic terrorism |

Groups or individuals whose activities are directed at elements of the U.S. government or society without foreign direction. |

Emergency Management Assistance Compact |

A congressionally ratified organization that provides form and structure to interstate mutual aid. |

Hazardous materials |

Chemical or toxic substances that pose a potential threat or risk to life or health. |

International terrorism |

Acts carried out by groups or individuals whose activities are foreign-based and/or directed by countries or groups outside the United States, or whose activities cross international boundaries. |

Mass shooting |

Shooting incident involving a lone gunman, or occasionally two gunmen, resulting in four or more deaths. |

Race riot |

Outbreak of a violent civil unrest in which race issues are a key factor. |

Safety data sheet |

Provides useful information regarding acceptable levels of toxin exposure, including data regarding the properties of a particular substance, the chemical’s risks, safety, and impacts on the environment; OSHA requires that MSDS be available to employees for potentially harmful substances handled in the workplace. |

Secondary hazard |

A technological hazard that occurs as the result of a primary natural event. |

Technological hazard |

Incident that occurs when hazardous materials are used, transported, or disposed of improperly and the materials are released into a community. |

Terrorism |

The unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives. |

Assessing Your Understanding

Summary Questions

1. The United States has experienced more natural hazards than human-made hazards. True or False?

2. Which of the following would be an intentional human-made hazard?

a. Oil spill

b. Train derailment

c. Anthrax attack

d. Fire

3. The all-hazards approach is a way for federal, state and local agencies to deal with both human-made and natural hazards. True or False?

4. The Olympic bombing in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1996 was an act of international terrorism. True or False?

5. The riots in Los Angeles in 1992 would be classified as

a. An accident

b. Domestic terrorism

c. A demonstration

d. Race riot

6. Acts of terrorism combine violence, motives, and a target. True or False?

7. Contamination from biological agents can be spread by wind and water. True or False?

8. Antiterrorism involves offensive measures to prevent terrorism. True or False?

9. Civil unrest can take place in which of the following forms?

a. Demonstration

b. Rally

c. Assembly

d. All of the above

10. Dizziness and changes in skin color are possible symptoms of hazardous material exposure. True or False?

11. Which of the following is a technological hazard?

a. Dry cleaner

b. Overturned petroleum tanker truck

c. Train crash

d. Chlorinated swimming pool

12. The EPA provides standards for chemical use. True or False?

13. The probable cause for most transportation-related technological hazards is

a. Weather

b. Computer failure

c. Human error

d. Leaks

14. A technological hazard that is triggered as a result of a natural hazard is a

a. Secondary hazard

b. Train derailment

c. Primary hazard

d. Disaster

15. Emergency response plans in the event of a nuclear incident define two different emergency planning zones. True or False?

16. A plume is

a. A measurement of radioactivity

b. Nuclear energy produced by a nuclear power plant

c. An emergency zone surrounding a nuclear power plant

d. A cloud-like formation of radioactive gases and particles

17. More U.S. residents have experienced a human-made hazard than a natural hazard. True or False?

18. Human-made hazards are likely to produce a more emotional response than natural hazards. True or False?

Review Questions

1. List three examples of accidental human-made hazards.

2. Name three agencies that can be used as resources for information about human-made hazards.

3. Why is FEMA encouraging communities to adopt the all-hazards approach?

4. What are some of the criteria that are used to define an act of terrorism?

5. Recall the United States’ official definition of terrorism.

6. Is it possible for an international terrorist attack to happen in the United States? Explain.

7. Give three examples of tactics used by terrorists.

8. Describe some of the underlying causes of civil unrest, including race riots.

9. Explain how medical facilities such as hospitals and research labs have contact with hazardous materials.

10. Identify five ways that hazardous materials can enter a community.

11. How do hazardous materials affect a home environment?

12. How has the 24-hour news cycle affected the public’s perception of human-made hazards?

Applying This Chapter

1. Human-made hazards are not as predictable as some natural hazards. We can, however, judge some of the risk by the hazards of the past. What, if any, human-made hazards have occurred in your area?

2. How would the all-hazards approach be used differently in New York City versus tornado-prone Indiana?

3. The media has covered certain measures that some larger cities have taken against terrorism (backpack searches on New York City subways, street closures in Washington, DC). Select a U.S. city and list any potential for terrorist activity and measures that have been taken to protect against the threat.

4. Imagine that a major public meeting has been scheduled about the proposed construction of a hazardous landfill in your community. You expect the meeting to be particularly contentious. What actions should the meeting organizers take to ensure a peaceful gathering?