It is vain to hope for the discovery of the first domestic corn cob, the first pottery vessel, the first hieroglyphic, or the first site where some other major breakthrough occurred. Such deviations from the preexisting pattern almost certainly took place in such a minor accidental way that these traces are not recoverable. More worthwhile would be an investigation of the mutual causal processes that amplify these tiny deviations into major changes in prehistoric culture.

KENT FLANNERY (1968, 85)

An effort is made here, however, to treat changes in the rate of growth as determined by the workings of the fundamental variables in the system, rather than as the consequence of exogenous forces.

WALT W. ROSTOW (1953, 17)

The secret of the growth of the city is in the process of deviation-amplifying mutual positive feedback networks rather than in the initial condition or in the initial kick. This process, rather than the initial condition, has generated the complexly structured city. It is in this sense that the deviation-amplifying mutual causal process is called “morphogenesis”.

MAGOROH MARUYAMA (1963, 166)

The development of Aegean civilisation is to be understood in terms of the growth and development in the various subsystems, the fields of activity which make up the culture system as a whole. In the discussion above these subsystems were defined, and the chapters of Part II of the present work examine each in turn, as it was during the crucial formative period of the third millennium BC.

Growth and development in the various individual fields of human activity in the third millennium are not in themselves sufficient, however, to explain the decisive changes which are seen in the Aegean world around 2000 BC. It is the basic theme of the present chapter that the decisive nature of such growth was determined by the interaction of the subsystems in the culture system of the Aegean, rather than simply in terms of the growth in each. For instance the effects of agricultural advances upon the social organisation, or of social factors upon craft production, are far more relevant to the growth of the system than the changes themselves, taken in isolation. Once again this question is discussed first in general terms. In chapter 21 the conclusions are applied specifically to the formation of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation.

Civilisation is not the product simply of growth in size, but of innovation: innovation which is accepted and becomes part of normal human behaviour, and so part of the shared environment. In seeking to explain civilisation we are seeking to analyse how and why man’s total environment changed, and how he came to produce the artificial environment which encompasses civilised man in every dimension of his existence. We are concerned, then, with innovations which influence this environment and the mechanisms which led to their assimilation.

This assimilation of innovations is related to the creation of variety, but not simply of a variety within established categories—for example a wider range of decorative motifs for a given range of ceramic objects. It is variety in the production of new categories, new activities, new products, not simply elaboration among the old ones. This idea is applicable to living systems in general: ‘Growth, a progressive, developmental, matter-energy process which occurs at all levels of systems, involves (a) increase in size -length, width, depth, volume—of the system, and commonly also (b) rise in the number of components in it; (c) increase in its complexity; (d) reorganization of relationships among its structures—subsystems and components—and their processes, including differentiation of specialised structures and patterns of action; and (e) increase in the amounts of matter-energy and information it processes’ (Miller 1965, 372).

Innovations occur all the time in any society: new ideas which crop up rather haphazardly, rather like mutations in the organic world. They are not individually predictable. But what is crucial is the response to these innovations. If the innovation is rejected, there is no effective change. But if accepted it can be further modified. Since the new activity will not be so bound by convention—society’s chief self-regulating mechanism—as is one longer established, it will itself be more open to yet further innovation. Of course the stabilising and regulating effects of habit and well-established behaviour patterns have the beneficial outcome of countering innovations which may disrupt the order of society. But they automatically inhibit change of any kind.

The early development of metallurgy suggests a striking instance of such inhibition. Hammered copper was used at numerous early neolithic sites in the Near East, and copper was even smelted at Çatal Hüyük. But, although pottery manufacture was already requiring the controlled production of high temperatures, and efficient and widespread metallurgy would thus have been perfectly possible, the bronze age in these areas did not begin until nearly three millennia later.

Two recent considerations of growth and change in human society are illuminating at this point. The first, by Boserup, examines the mechanism of growth in the subsistence subsystem. The notion of positive feedback, discussed in the last chapter, is here a particularly helpful one. The second, Rostow’s analysis of the conditions necessary for ‘takeoff’ in an economic subsystem, leads us to the central idea of the present chapter, that it is the interactions between subsystems, not merely within them, which are crucial for sustained growth. Just as the Boserup/Malthus controversy underlines the concept of feedback operating within the subsystem, so Rostow’s treatment leads to the consideration of feedback between the subsystems. It is here that the multiplier effect operates.

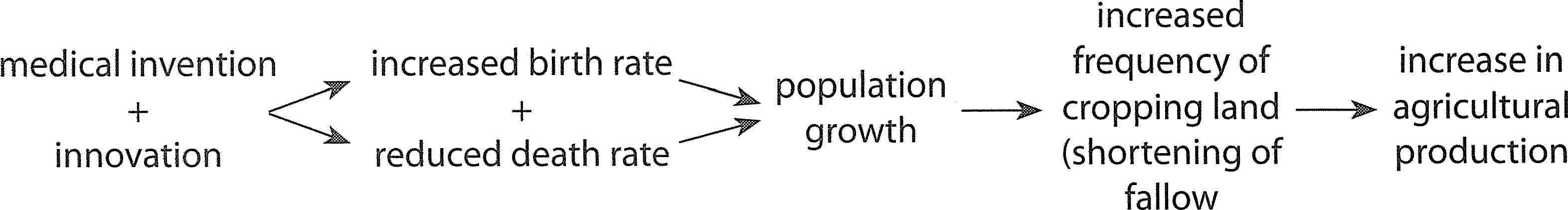

The model of human culture as a system composed of subsystems is especially appropriate for a consideration of the process of growth. To take a specific example, the disagreements with the views of Malthus which Boserup (1965) expresses in her informative work become much clearer when viewed in this light. She is concerned particularly with farming techniques, and with the transition which has taken place in many parts of the world from extensive farming, where much of the land lies fallow, to intensive farming. Her thesis is essentially the opposite of that of Malthus and his followers: ‘Their reasoning is based on the assumption that the food supply for the human race is essentially inelastic, and this lack of elasticity is the main factor governing population growth. Thus population growth is seen as the dependent variable, determined by preceding changes in agricultural productivity, which, in their terms are explained as the result of extraneous factors such as the fortuitous factor of technical invention and imitation’ (Boserup 1965, 11).

She explains that the subsistence pattern adopted in a given region is not simply determined by geographical factors: it is governed to a large extent by the population which that land has to support, and by the population’s own decisions about agricultural techniques. For her ‘population growth is ... the independent variable which in turn is a major factor in determining agricultural developments.’ And the intensity with which the land is cultivated is, to a large extent, a function of the population which it has to support.

One of the easiest ways to cultivate the land (in terms of labour costs per unit of output) is forest fallow cultivation, where, after clearance by fire, and cropping for a year or two, the land is left uncultivated for a couple of decades. Only with the need to increase the yield per unit area (albeit often, at first, at the cost of increasing also the labour cost per unit output) is a change to a short fallow system undertaken. ‘It is more reasonable to regard the process of agricultural change in primitive communities as an adaptation to gradually increasing population densities, brought about by changes in the rate of natural population growth or immigration’ (Boserup 1965, 118). The logical structure of her explanation may be analysed as follows:

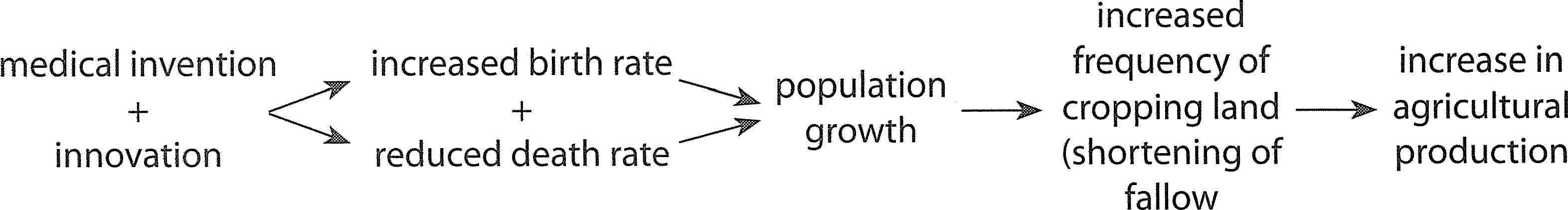

This conflict between Boserup and Malthus seems in essence an instance of the ‘which came first’ problem, the universal difficulty in distinguishing between cause and effect. As Boserup herself has written (1965, 117): ‘It is often difficult or impossible to determine through historical research whether the demographic change was the cause or the effect of changes in agricultural methods.’ I suggest that a clearer summary of the position can be obtained by accepting that population and agricultural methods are mutually influential, and by abandoning altogether the search for an ‘independent variable.’ Boserup’s work has indeed been criticised as stressing too heavily the supposed ‘independence’ of population growth (as well as the flexibility in response to it of the cultivation system), and to recognise the interdependence of such factors would seem to do more justice to the complexity of the situation. The factors may be linked by a feedback loop, with which systems theory is particularly equipped to deal.

Admittedly the feedback loop only functions under certain conditions: the increase in production only implies increased nutrition if it is actually a per capita increase in production. But undoubtedly an increase in production increases the number of persons who can be fed at a given daily dietary intake.

If the population growth is to be sustained, either the ‘independent variables’ favouring population growth (such as improved medical facilities) must continue to act in such a way as to favour population growth, or there has to be some positive feedback in the system, whereby the increase in food production favours further population growth.

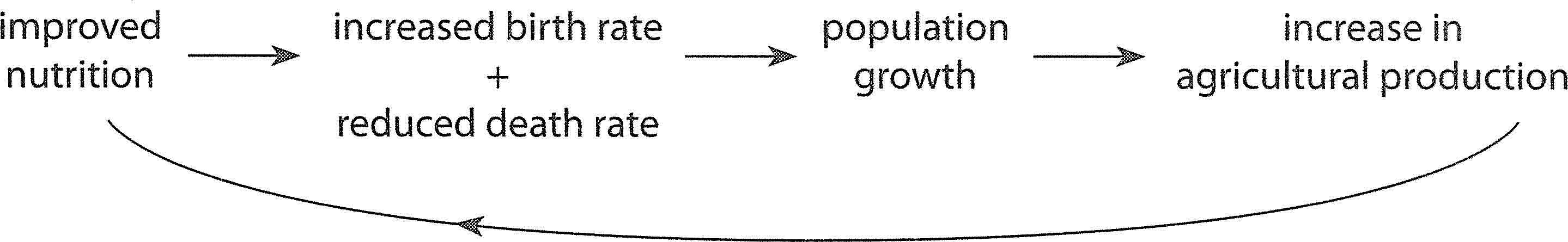

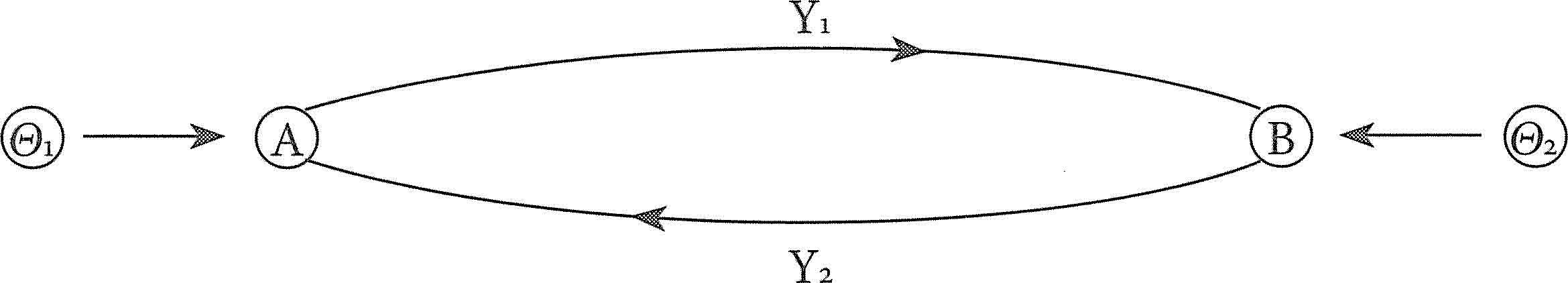

Situations of this kind are well known in most branches of systems theory, from biology to cybernetics. The closest analogy, perhaps, lies in the field of economic theory, where Tustin (1953, 35), for instance, illustrated a scheme of dependence of this kind, for a closed sequence system for investment (I) and income (Y).

The closed sequence is supposed to be constituted by a response or feedback proportional to rate-of change of income Y with a time delay t. And given these assumptions, the growth of the system (i.e. the future values of Y) can be predicted.

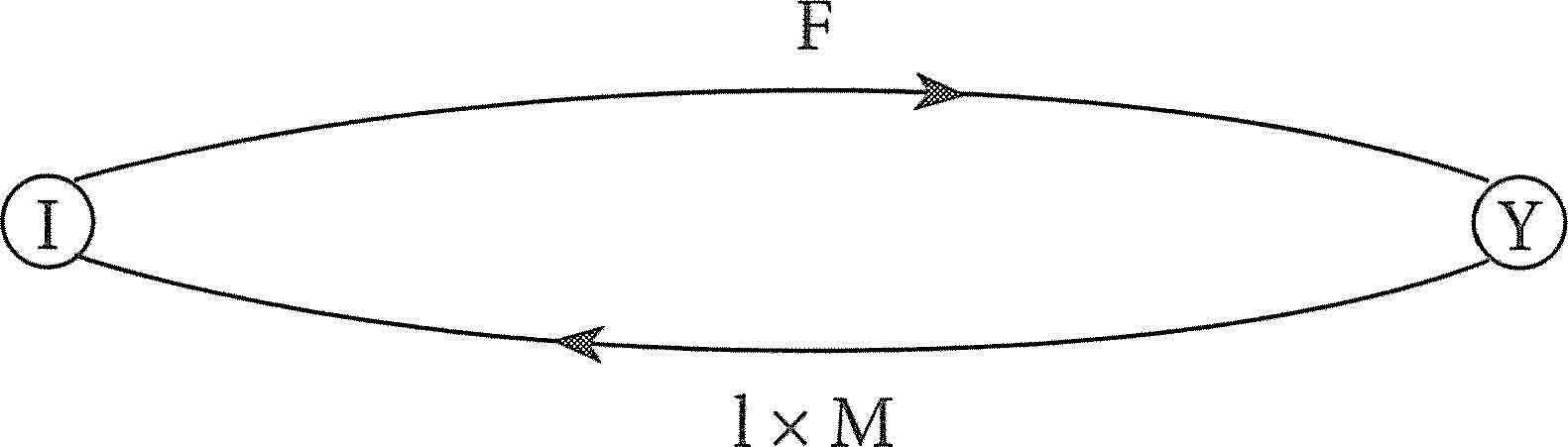

This example is, of course, a closed system, where all outside influences are excluded from consideration, and all living systems, including human societies, are open systems. But Tustin (1953, 159) later discussed how the nature of the interactions of two interdependent variables, which are also subject to independent outside influences, may be studied.

Here Y1 represents that circumstance that A affects B, and Y2 that B affects A. The variation of quantities exogenous to this pair is represented in the schema by inputs Θ1 and Θ2. Tustin’s discussion clarifies some of the features of such a relationship, and especially the assumptions and the information which are needed in order to produce an explicit analysis. In the case of interactions between population (A) and food production (B) the relationships are complicated. Y2 implies that the level of food production sets an upper limit upon the population which can be supported, but it does not itself determine the population, which is governed also by other factors (Θ1). And Y1 indicates that the population available sets restraints on the amount of food which can be produced. Boserup’s thesis is that in governing the mode of food production as well as determining the available work force, the population is the significant determinant for the level of food production. But other variables also govern the food production.

Regrettably it is difficult to give these relationships precise quantitative expression, but even so the form of Tustin’s analysis, and the necessity it creates for the explicit formulation of underlying assumptions, are useful in suggesting the scope of a systems analysis made under ideal circumstances. His formulations, for instance, make entirely clear how growth cycles occur under certain conditions, and this is of relevance to population studies, even if some of the variables cannot be determined with precision.

In Boserup’s analysis, the trend towards shorter fallow which she describes does not in itself amount to true economic growth, since the output per man-hour is at first diminished. But here she indicates ‘secondary effects’ which are relevant to our main concern, the emergence of civilisation. Amongst these are the compulsion of agricultural workers to work harder, and the division of labour, accompanying improved communications and better education which the increased population density favours. ‘The important corollary of this is that primitive communities with sustained population growth have a better chance to get into a process of genuine economic development than primitive communities with stagnant or declining population’ (Boserup 1965, 118).

The conclusion which Boserup reaches, although formulated with the problems of the underdeveloped and developing countries of the modern world chiefly in mind, seem particularly relevant to the development of early civilisations, including that of the Aegean:

‘According to the theory propounded above, a period of sustained population growth would first have the effect of lowering the output per man-hour in agriculture, but in the long term the effect might be to raise labour productivity in other activities, and eventually to raise output per man hour also in agriculture. In a development pattern of this kind there is likely to be an intermediary stage where labour productivity in agriculture is declining while that of other activities is increasing. This period is likely to be one of considerable political and social tension, because people in rural areas, instead of voluntarily accepting the harder toil of more intensive agriculture will seek to obtain more remunerative and less arduous work in non-agricultural occupations.’

Here Boserup is, in effect, asserting the connectedness of the subsystems of the society, since social factors, efficiency of communication and work-preferences now bear significantly upon the development of agriculture. The growth and development of farming cannot be analysed adequately without taking into consideration the other subsystems of the culture.

This analysis of agricultural growth is quoted here at some length, not simply because it is informative in its own right. It touches also on the crucial question of the impact upon the growth and development of a given subsystem of those ‘secondary effects’ which its developments have produced in other subsystems, and which in turn have their influence on the further growth of the subsystem in question. An economic analysis by W. W. Rostow is helpful in indicating more clearly the nature of these interactions.

A second informative and stimulating approach to economic growth focuses on just this problem of the interaction of different factors (Rostow 1953). And again the analysis is in terms of factors primarily within the system. Rostow’s own interest again lies in the problems of developing countries, and the circumstances favourable to their economic ‘take-off’. Our own lies in the possible analogy which this suggests for the ‘take-off’ leading to the formation of early civilisations, and on the insight it may give into the way interactions operate between the component subsystems of the culture.

The analogy is not, of course, a complete one, since none of the early civilisations which we have in mind move beyond Rostow’s traditional stage. Yet there are interesting and suggestive parallels between the process of growth from traditional to industrial civilisation, and that from subsistence economy to early civilisation, the transformation which we are seeking to explain.

Rostow’s approach is basically one of common sense: its originality lies in a willingness to consider a multiplicity of long-term factors, and above all in the attempt ‘to treat changes in the rate of growth as determined by the workings of the fundamental variables in the system rather than as the consequence of exogenous forces’. It is this which makes his work relevant to the present problem.

His analysis of the forces governing changes involves three basic statements about the workings of society:

1. The economic output is determined by the size of the working force, the society’s stock of capital, and its stock of knowledge. The rate of growth is therefore a function of the rate of change of these factors.

2. The first of these factors is itself governed by five ‘economic subvariables’: these comprise the rates of birth and death (prior and current), the role of women and children in the working force, and the skill and degree of effort of the working force.

The second factor, the size and productivity of capital, is seen as governed by six subvariables, namely the volume of research in pure and applied science, the proportion accepted of the flow of innovations, the balance between consumption and current investment, and the yield from additions to capital stock.

3. These economic subvariables are themselves seen as dependent upon six further variables or propensities, ‘the human determinants of economic action’: the propensity:

to develop fundamental science

to apply science to economic ends

to accept innovations

to seek material advance

to consume

to have children.

These ‘propensities’ are in turn seen as ‘a function of the prior long-period operation of economic, social and political forces which determine the current social fabric, institutions and effective political theory of the institution’. Clearly these propositions do not offer an explicit quantitative analysis of the growth which they set out to explain. But they ‘are designed to constitute a link between the domain of the conventional economist on the one hand, and the sociologist, anthropologist, psychologist and historian on the other.... They also aim to provide a focus for the efforts of non-economic analysis interested in economic phenomena ....’

Rostow’s book goes on to analyse the problems of modem developing societies in these terms. The interest of these ideas here is the explicit realisation ‘that actions which result in economic advance need not be motivated by economic goals’. The analysis of an economic subsystem is dependent on ‘propensities’—such as the acceptance of innovation, or consumption, which are only in part economic and are not necessarily governed by economic factors. Indeed of these six propensities only the last two fall directly within the scope of Malinowski’s ‘primary needs’, mentioned in chapter 2 (Malinowski 1960, 91).

These are variables which, while endogenous to the society in question, may be regarded as exogenous to the economic subsystem. Once again the interrelations between subsystems are seen as crucial. ‘Economic action is ... the outcome of a complex process of balancing material advance against other human objectives ....’

In the second part of this book the developments in the Aegean early bronze age, which led to the establishing of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation, will be considered. They may profitably be regarded in this way, taking economic changes not in isolation but within the context of their impact on the society as a whole. For it is this impact, most clearly evident in social terms, which determines the long-term features of the economic progress in question. It is clear that the early bronze age of the Aegean was a period of change. Many innovations were widely accepted in the Aegean at this time and subsequently, when an international spirit, a cosmopolitan feeling, can be detected. The obvious superiority of the metal tools and weapons, for instance, over their stone counterparts may have led to their rapid acceptance. This in turn led to the adoption of other new methods and ideas. This was a time of change, change induced indeed partly by the sudden significance of metal. And in such times of change, as Boserup hinted, other innovations seem to have found ready acceptance. The propensity to accept innovations does indeed seem a significant factor in considering these developments.

The metallurgical and other technological developments discussed in chapters 16 and 17 do indeed show a notable dynamism in the development and application of new techniques and processes. The bearing of Rostow’s first two propensities is obvious, although in the early Aegean there was hardly a valid distinction between pure and applied science.

Above all, the propensity to seek material advance, and to consume, are factors which are relevant to the origins of Aegean civilisation. They are often overlooked in analyses of culture change, or even dismissed as ‘superficial reductionist’. (It must none the less be admitted that the simple naming of ‘propensities’ is in itself far from an explanation of growth, but merely a first step in that sense.) For instance, the development of metallurgy actually created new forms of wealth, and indeed new forms of consumption. The propensity to consume was undoubtedly given new scope by its introduction.

Probably, however, in most prehistoric societies the propensity to seek material advance was still limited to a large extent by social factors. A Mycenaean prince, for instance, might well deliberately accumulate wealth in order to dazzle and influence both his subordinates and his peers by its display. But we may question whether there was any very high degree of social mobility at this time, and whether social advance could effectively be secured by increased work or production.

The analysis does, however, suggest an emphasis on one feature common to all civilisations: a willingness to invest income and hence to accumulate what may be regarded as capital. Both goods and labour were lavishly employed in the construction of significant religious or social centres, often of palaces. At first sight much of this investment was unproductive, contributing solely to the magnificent appointments of the palace or to the rich burial goods which accompanied the prince and his family to the grave. But this is to overlook the socially cohesive effects of such investment. And the production of these increasingly magnificent objects (the increase itself a sign of willingness to accept innovation) was the only possible way of conducting ‘research’ in the fields of pure or applied science. In prehistoric times most knowledge was practical knowledge—and this does not, of course, exclude religious experience, since religion is itself to be regarded in functional terms as a special technology. Innovations must have arisen most frequently not from deliberate research and its application, but from the ‘spin off’ consequent upon the developing production processes employed in the palace or temple workshops and beyond.

The palace, as the area of highest population density and the location of the majority of specialist processes (at least in the Minoan-Mycenaean world), from metallurgy to accounting, constituted—together with its implicit social system—the main capital stock of the community. And ‘whether a rate of growth can be sustained depends on whether investment ... is sustained’ (Rostow 1953, 95). The developing social system ensured that both investment and the rate of growth were indeed sustained.

This emphasis upon the propensities to consume and to seek material advance is of course not a new idea, and many economists stress that sustained growth over a considerable period requires modifications of economic and perhaps social organisation. As J. K. Mehta has written (1964, 95), continued growth of real income depends ‘on the extended use of the ability to plan and organise human efforts. It is organisation whose elasticity can ensure a sustained rate of growth of national income.

‘If there is any factor that possesses elasticity in a degree that we need for growth, it is organisation. This factor, which is perhaps capable of stretching itself to any required limit, is behind growth. But circumstances must be favourable to enable it to stretch itself. These circumstances are related in the final analysis to the behaviour of producers (determined partly by their habits and partly by their psychological reaction to consumers’ behaviour) and the behaviour of consumers.

‘For the study of growth it is necessary, therefore, to make some plausible assumptions about the behaviour of buyers of productive services (producers) and those of consumption-goods (consumers).’

Of course the language of economics, formulated where a money currency establishes a precise and stable equivalence between different kinds of goods and services, cannot be applied to societies without a formal exchange system. It is absurd to read into early societies the economic concepts of modern marketing and currency. Such statements as these cannot be directly applied, but at the level of analogy they are certainly indicative of relevant factors.

At a certain point, indeed, the analogy between economic growth and the growth of a culture or civilisation breaks down. In the first place an important criterion which the economist takes to indicate the transition from a preponderantly agricultural basis to an industrial one is the rate of increase in per capita output. In the essentially nonindustrial society of the prehistoric Aegean, even at the peak of its development, the rate of increase, however measured, cannot have been very great. Moreover, such an economic analysis, while refreshingly considering the effect of nonmaterial factors on economic growth, is still restricted in its scope to the growth of the economy, not to the development of the culture as a whole. The analysis does not, therefore, offer full scope for a consideration of the interactions of all the factors relevant to this larger problem, although it works in the same sense. But it is precisely this question, as to how changes in one field of human activity—in one subsystem of society—produce changes in another, which requires further consideration.

One of the distinguishing features of human societies is the extent to which changes within one subsystem of society bear upon other subsystems. Population does not simply grow, for instance, and then reach a stable level, governed purely by environmental factors, as it might in the case of most animal populations. Instead a dynamic interaction is set up between the population level and the means of food production. There is innovation, and the acceptance of innovation. A new adaptation is seen: a new farming mode, which amounts to a new structure of food-production procedures, a new configuration among human activities. In the terms discussed above, there is very considerable elasticity in organisation.

The growth which we are here considering consists in the establishment (and survival) of new relationships, new patterns of activity. This often implies the desuetude of many of the old relationships and activities, so that the changes which result are often irreversible. The analogy in the organic world of nature is here not with the growth of a single member of a species (the ontogeny), since this implies no real innovations in patterns and relationships already established, and is largely a question of size, of scale. It lies rather with the evolution of a new species (the phylogeny) where real innovatory changes, the result in this case of mutation, lead to new adaptations and the irreversible movement away from old ones.

Systems theory has indeed made clear to us the way in which ‘regulators’ can achieve a dynamic balance in a system. And most branches of human activity, as we saw in the last chapter, are governed in the same way. Human conduct is regulated by all the rules, pressures and incentives of society: there are ways things are usually done, and things which are not done. Indeed it is generally normal in a human culture for things to go on much as they have before.

Here, however, the problem is a different one. The regulatory efficacity of culture is accepted. The question is now the opposite one—how and why does it change or grow?

Growth in numbers or in size is itself inhibited by the regulatory mechanisms. When the birth rate rises very rapidly, for instance, the death rate may also rise, and population growth is limited. These restricting mechanisms can only be overcome by deviation-amplifying mechanisms which actually favour growth of certain kinds. This is the positive feedback also discussed above. In favourable circumstances ‘one thing leads to another’. A change, for instance an increase in capital investment, leads to an increase in production. And this outcome works now to amplify the initial change by allowing a further increase in investment. In this way a ‘growth cycle’ develops, subject to what the economist calls the Law of Diminishing Returns. After a period of sustained change or growth, further change (e.g. further investment increase) no longer has so large an effect as before (e.g. on output). A kind of saturation is reached, and the growth ends. The feedback, in other words, is no longer positive.

Once again there are analogies in chemistry: we have already seen above that when a chemical reaction is reversible, a negative-feedback regulator operates, designated Le Châtelier’s Principle. But when the reaction is irreversible this does not hold. In some reactions, which are self-catalysing, the faster a reaction is taking place the faster its rate increases: this is a positive feedback situation. But later, often as the available resources are used up, the reaction rate falls again: by analogy we may say that the law of diminishing returns is operating.

The growth of human societies is not always subject to this law of diminishing returns precisely because the underlying structure is itself changed in the growth process, just as in the economic situation summarised by Mehta above. Innovations arrest or negate the operation of the usual limiting factors. This change of structure is something the cyberneticist can hardly handle yet—the structures of the systems with which he deals do not generally transform themselves into something different.

The key to this process in human cultural development lies in precisely the interconnectedness, identified in the preceding section, among the different activities of the individual in society, the interdependence of the subsystems of society. There is, indeed, a new kind of positive feedback among innovations—an innovation in one subsystem tends to favour innovations (and their acceptance) in another, in a manner quite foreign to the other species of the animal world. (Although there may be a superficial analogy with the working of ‘explosive evolution’ in organic evolutionary development.)

I propose to term this mutual interaction in different fields of activity, this property of human systems that an innovation (and its acceptance) in one subsystem favours innovation in another, this interdependence among subsystems which alone can sustain prolonged growth, the multiplier effect.

This term does not simply imply positive feedback, as in the ‘accelerator’ and ‘multiplier’ of the economists. It indicates the process whereby changes in one field of human activity can significantly influence changes of quite a different kind in another field. The following definition of the multiplier effect seeks to emphasise this distinction from the usual working of positive feedback within a single subsystem:

Changes or innovations occurring in one field of human activity (in one subsystem of a culture) sometimes act so as to favour changes in other fields (in other subsystems). The multiplier effect is said to operate when these induced changes in one or more subsystems themselves act so as to enhance the original changes in the first subsystem.

This, then, is a special kind of positive feedback, reaching across between the different fields of human activity. The term multiplier used in this sense implies rather more (although with less precision) than the technical term ‘multiplier’ in economic theory, as formulated by Kahn and used by Keynes with reference to employment and income (Keynes 1937, 115–16). Already it has been extended beyond this original use by geographers who speak of regional multipliers (cf. Chisholm 1966, 99) to elucidate the way in which industrial expansion, within a specified area, has secondary effects there, arising from the presence of the new population and the need for service industries:

‘This analysis stresses the interrelations of sectors within a regional economy and the spread of impulses originating in anyone sector to all other sectors either directly or indirectly. Such spreading in essence has a multiplying result. Through the continuous back and forth play of forces (or round-by-round process of interaction), such spreading leads to a series of effects on each sector, including the original one, although these effects need not always be in the same direction, and of significant magnitude. The relevance of multiplier studies for programming regional development is obvious. It neatly points up how growth in one sector induces growth in another. The relevance of such studies for understanding regional cycles is also obvious as soon as we recognise that some impulses may be positive, others negative; some expansionary, others deflationary’ (Isard 1960, 189).

Here, however, we are concerned not solely with different sectors in the economy of a cultural region, but in the different sectors in the culture as a whole, without restricting the discussion to purely material or economic considerations. We are extending the meaning of the term beyond its conventional one as an aid to analysis of feedback effects within the economic system. In discussing the growth and development of culture the independent growth within the component subsystems is naturally itself of interest. But we are now using the term to designate the effect of their mutual interconnectedness, which favours positive feedback between the different components of the culture system as a whole.

Identification of the multiplier effect in the culture system is illuminating not solely because it allows us to visualise, and in this sense understand, the growth of a system in terms of factors endogenous to it. Above all it focuses our attention on their interrelationship. It is a commonplace of ‘functional’ anthropology that all aspects of a human culture are ultimately interrelated, and that changes in one aspect should affect other aspects of the culture. The definition of the multiplier effect in the field of human culture is an invitation to investigate the mechanisms of this interconnectedness.

When the multiplier effect comes into operation, and remains in operation, there is sustained and rapid growth, not merely in the scale of the systems of the culture but in their structure. Changes in one area of human experience lead to developments in another. In this way the created environment is enlarged in many dimensions, and itself becomes more complex. This is, as we have seen, something more complicated than the operation of a simple positive feedback, causing growth and amplifying the processes already present: it is a feedback system with coupled subsystems, favouring innovation.

The conditions for the multiplier effect to come into operation in such a way as to result in sustained growth in the different sectors of the culture require close consideration. Some writers have spoken of a threshold or take-off point beyond which striking developments occur. To investigate this threshold is essentially to seek the circumstances which bring the multiplier effect into active operation.

When the emergence of civilisation is considered, it seems that the crucial requirement is that there should exist the possibility for sustained growth (and for positive feedback) in at least two of the subsystems of the culture. Clearly, if none of the subsystems were free, through the favourable influence of changes in the society, to grow and develop (e.g. agricultural production to increase through the adoption of more intensive farming procedures), the culture has no potential for growth. And if only one subsystem develops in this way, and the multiplier effect does not operate, the nature of the culture as a whole will not fundamentally be changed.

The ‘temple’ culture of Malta seems an obvious case where a single subsystem, involving religious activities and the construction of the great temples, clearly underwent dramatic expansive developments. But for whatever reason this does not seem to have produced detectable positive developments in other subsystems (whether technological or economic). Why this should have been so remains to be investigated—perhaps limited agricultural potential, and the lack of raw metals were significant negative factors—but the outcome was not a civilisation, merely a neolithic culture boasting remarkably sophisticated temples.

It seems that no single factor, however striking its growth, can of itself produce changes in the structure of the culture. For a ‘take-off’ at least two systems must be changing and mutually influencing their changes.

The Sumerian civilisation has at times been attributed primarily to the invention of irrigation, a single factor which supposedly yielded a food surplus, and made possible the Mesopotamian class structure, with its priests and princes, and the growth of the city. This notion of a food ‘surplus’ as the ‘cause’ of further growth has been effectively demolished by Harry Pearson (1957, 320) and George Dalton (1960; 1963). It is inevitable, of course, that any society which has non-food-producing specialists of any kind must have a subsistence situation whereby one food-producer can produce more than he eats. But the term ‘surplus’ in a non-market, non-money economy is without meaning, indeed a contradiction (Dalton 1960, 485): if it refers to an experienced growth of output, it would be better to say so. As Dalton (1963, 389) has forcefully asserted: ‘To attribute the existence of non-food producers to a food surplus—in the sense that a growth in food supply actively caused the priests and rulers to arise—is, to put it bluntly, silly.’ When French farmers dump their artichokes in the road during a glut, there may well be a surplus, but in what sense is the Sumerian peasant’s contribution to the temple ‘surplus’, or the goods destroyed in a potlatch? To regard all subsistence products not actually eaten by the producer and his family as ‘surplus’, and to ignore the real significance of activities even so apparently wasteful as a potlatch, is to make so total a distinction between the subsistence economy of the neolithic and the craft economy of early civilisations that the gap cannot be bridged. As Pearson (1957, 339) has said, referring to the many societies where ‘potential surpluses’ are available (i.e. where an increase in food production would be possible): ‘What counts is the institutional means for bringing them to life. And these means for calling forth the special effort, setting aside the extra amount, devising the surplus, are as wide and varied as the organisation of the economic process itself’. Dalton (1963, 392) points out: ‘In some circumstances a growth in food supply may be a necessary condition for social change to come about: it is never a sufficient condition’. This is very relevant to Minoan-Mycenaean society, as doubtless to all early civilisations. Indeed he goes on to state: ‘In other circumstances, as we are now learning from economic development in primitive areas, just the opposite may be the case: social change may be a necessary condition for allowing an increase in the food supply to take place.’

Since civilisation, with its artificial environment, does imply some specialisation, every civilisation must have an economy which has progressed in some senses beyond a subsistence economy. But this does not mean that the growth of civilisation was ‘caused’ by improved food-production techniques, which may indeed in some cases have long been available. In many cases, I suggest, it did in fact come about through innovations in such techniques coupled with social and other developments which at the same time made these subsistence improvements both possible and desirable.

Robert Adams, on the other hand (1966, 12), draws ‘the conclusion that the transformation at the core of the Urban Revolution lay in the realm of social organisation’. This view now seems to tend rather towards the other extreme, and recognise as ‘cause’ what was previously identified as ‘effect’, and vice versa. One is reminded here of the rather similar divergence in the views of Malthus and Boserup, where the former regarded the food supply as the ‘independent variable’, and the latter the population density. For indeed, as Adams himself has stressed, the social organisation could not have emerged without the possibility of increased per capita food production among the agricultural producers. The two developments are coupled and cannot with profit separately be labelled ‘cause’ and’ effect’.

The implication of this view, which can indeed be formulated as a testable prediction, is that we shall not expect the archaeological record for the early development of a civilisation to show greatly improved production techniques (e.g. irrigation) and ‘surplus’ storage facilities arising prior to, or without evidence of social stratification (e.g. palaces) or religious specialisation (e.g. temples). Nor shall we, in the cases where the successful transition to civilisation was later accomplished, expect these social and religious advances to have developed markedly without developments also in food production. On the contrary, the two were linked by the multiplier effect, and it was their coupled expansion which led to rapid changes in the culture in general.

In the same sense, the development and increase of trade, for example in the early Aegean, cannot alone be regarded as the principal factor leading to the development there of civilisation. Without its strong interaction with other sectors of the culture, such as social organisation, the multiplier effect could not effectively have operated.

We may even suggest that social stratification itself is not automatically a necessary contributing element in the growth of civilisation, although the emergence of certain new social structures would indeed seem inevitable. The documented remains of the Indus civilisation, for example, are notably lacking in evidence for great personal wealth, and so far, although public and communal buildings are known, there are no great temples or rich palaces. We can imagine (perhaps a shade frivolously) a socialist state, with communes and with specialists, yet without social stratification in the sense of a hierarchical, rank-order structure in the society. Such a state would have a developed social organisation, of course, but not a pronounced social stratification.

It is, of course, at the level of the individual in society that the multiplier effect actually operates. And it is through the individual that social pressures, for instance, have an economic significance, for, as outlined in chapter 2, the various subsystems of the culture are linked at the level of the individual. It is therefore by a consideration in terms of individuals, on a micro-economic scale, that the precise mode of operation of the multiplier effect must be elucidated.

On a micro - economic scale, then, the farmer in an ideally simplified neolithic society produces enough for the needs of himself and his family. There is little point in producing much more food than they can eat, since there would be nothing for him to do with it.’ (He thus avoids a surplus, except in occasional years of unexpectedly high crop yields.) His needs are satisfied. His environment is stable.

Various innovations may work to change this situation. The social subsystem may require of him some conspicuous act of generosity or prosperity (such as a potlatch contribution) to maintain or enhance his prestige. Here then is a crucial new concept (although one implied in Rostow’s schema)—a derived secondary need in Malinowski’s sense.

Equally some personal ill- for example a sudden death in the family—may require him to propitiate the supernatural forces by some means. Or he may believe (in common with his society) that the efficiency of the world—for example the fertility of his crops and cattle—can only be ensured by his participation in the religious order. Here religious dread, or some specifically formulated cosmological concept, require certain actions: the projective subsystem imposes material obligations.

Or warfare between villages may necessitate his neglecting his crops, and perhaps making material contributions of various kinds. Here competition, a further ‘derived need’, is operative (cf. Rapaport 1967).

I find it impossible to envisage an explanation for change and growth in society without some reference to the ‘new needs’ which the operation of such factors produces, the material demands and obligations arising from social and religious considerations. Man shows great mobility or elasticity in his requirements: workers today will withdraw their labour on the grounds of unsatisfactory conditions, which would have been accepted as generous a century ago. A telephone, a car, a television set are legitimate needs in the city today, while a generation or two ago they belonged to the realm of fantasy No explanation for culture change which fails to acknowledge the appearance of such new needs can be effective.

Of course there is evidence for competition and display among other animal species (Wynne-Edwards 1962), and it is not their existence, but the way the society is adapted to facilitate them, which is a unique feature of human culture. And the line of argument can become a circular one if we ‘explain’ a new feature ‘because’ we believe there to have been a ‘need’ for it. A more thorough investigation of the nature and working of these ‘needs’ and ‘propensities’ is demanded.

Some of the developments within a culture can indeed be explained without reference to ‘secondary needs’ of this kind. We can suggest that any society (or indeed animal) seeks improved control over its natural environment. The system, as we have seen, works to minimise the effect of a disturbing influence. Moreover it will tend to do so with the expenditure of least energy. Man, like nature ‘takes always the shortest path, for it is the most natural’ (Marcus Aurelius, Meditations). ‘La natura non opera con l’intervento di molte cose quello che si può fare col mezo di poche’ (Galileo, Dialoghi dei Massimi Sistemi, Day 2). We can apply the Law of Parsimony to man as well as to nature (Zipf 1949, 5). Any increase in efficiency, involving less work for the same results, may a priori seem an improvement. And yet even here there are many instances where cultural factors appear to operate in the opposite sense by impeding the acceptance of innovations which would increase efficiency in certain sectors.

Without acknowledging competition as a significant factor there is no way of explaining, for example, the introduction of weapons. And, above all, without acknowledging a desire for prestige, and the principle that prestige frequently relates to wealth, it is difficult to explain social stratification. These propositions do not, however, amount to natural or universal laws for human behaviour—in a monastic order of poverty, for instance, the monk who cannot bring himself to discard earthly riches may be little esteemed.

Most of man’s activities exist in many dimensions, as the discussion in chapter 2 sought to show. To draw a further analogy with economics, man’s ‘currencies’ within the different dimensions are to some extent interchangeable. Prestige can be related to economic gain, while religious fulfilment may adequately be substituted for the latter. The notion that ‘every man has his price’ implies that material goods can be set against a ‘currency’ in the social dimension, such as honour. Moreover in each dimension man shows considerable income elasticity of demand: ‘the more you have, the more you want’. In non-monetary and non-market societies these are not scalar quantities—a man may set life above love, love above honour, and honour above life—and no universal equation is possible. As Rostow implies, it is this interaction between the various dimensions of human existence which, together with man’s income elasticity of demand in various fields, makes culture growth possible.

A palace, such as is found in many early civilisations, has functions which far exceed the primary one of providing bodily comfort for a segment of the community. And a temple, whatever its history, is referable also to a quality or propensity in human beings not discernible in other animals. No explanation of civilisation can proceed without recognising this basic difference in potential among species, although we cannot expect to explain these fundamental circumstances—that is the province of psychology, of physiology, of cybernetics perhaps, and of biochemistry. Our explanation must start by assuming that all societies of men share these potentialities, for at present there is no convincing evidence that they do not. Obviously an explanation in terms of group or racial ‘superiority’ or ‘creativity’ is to be rejected at once, unless there are striking and conclusive new observations in anthropological science to warrant such a theory. The explanation which we are seeking operates, rather, within the field of man-environment interactions, to trace how innovations and their acceptance produced irreversible changes in certain cultures, leading in some cases to civilisation.

The story of the development of these innate human potentialities during the process whereby Homo sapiens emerged from his predecessors belongs largely to the field of physical anthropology. But most anthropologists believe that man as born today does not differ significantly from man as bom 10,000 years ago. In analysing the genesis of a civilisation we are operating, therefore, in the domain of cultural development and evolution, not of strictly biological evolution.

As this chapter has tried to outline, we have a possible formula for the explanation of culture change. It is accepted that societies and cultures live in a state of equilibrium: the subsystems which operate in the society are regulated so as to minimise the disturbances to the human environment caused by fluctuations in the natural environment, by outside human agencies or by innovations within the society. For any significant change to take place the innovations must be linked in a deviation-amplifying mutual causal system: the innovation produces effects which favour the further development of the innovation. In some cases the innovation arising in one subsystem has marked effects in other subsystems: this is a feature specifically of human societies with their goal mobility, where needs or aims in one dimension are sublimated to other dimensions. In such a case, if positive feedback occurs, the multiplier effect can come into operation: coupled developments occur in both subsystems, and the innovation is favoured. When the structure of the subsystems is such that marked change can occur in them (for instance when a technological threshold such as the invention of metal casting, or the sowing of grain, can be surmounted) a cultural ‘take-off’ is possible. Most or all of the subsystems of the society will then undergo marked structural change.

The operation of the multiplier effect—of positive feedback situations within and between coupled subsystems—produces a ‘revolution’ in the sense intended by Gordon Childe. This applies equally to the Neolithic, Urban and Industrial Revolutions. Each may take a long time to mature, since these are not sudden quantum shifts, but continuous processes of change. But in each case the rate of innovation and the speed of structural change in the society are much faster over a considerable period, which we regard as the duration of the revolution itself.

Of course these ‘subsystems’ and the ‘positive feedback’ between them are theoretical constructs, terms which we have ourselves created in order to talk about such changes. But if they lead us to formulate new hypotheses which can be tested in the archaeological record—to posit, for instance, a correlation between one observable factor and another in a given culture—then they are fruitful constructs. A model such as this offers many features as yet unexplored by archaeologists and anthropologists: it might even be capable of sustaining exact and quantitative formulations, were sufficiently comprehensive archaeological data available.

This is the model for culture change which we shall set out to apply in considering the origins of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation. First, in Part I, it will be necessary to establish the relevant sequence of cultures, establishing their spatial and temporal relationships. Then it is proposed, always subject to the limitations imposed by the rather fragmentary data, to look at the workings of the several subsystems operating in the Aegean cultures of the time. This survey is undertaken in Part II. And finally, in chapter 21, a preliminary and speculative attempt will be made to see, in terms of the multiplier effect, how far the interactions of these different sections of society can make intelligible to us, and in this sense explain, the processes which led to the formation of Aegean civilisation.