The trouble is that most explanations don’t explain.

LOUIS MORDELL

Aegean civilisation, in the sense established above, is first seen in Crete a little before 2000 BC, and several centuries after the development of urban society in Mesopotamia. The main developments which led up to the new and sophisticated palace civilisation are often regarded simply as the result of the contacts with more advanced and more highly organised lands to the east which took place during the third millennium. In later chapters this view is examined in detail and rejected. The evidence is, on the contrary, interpreted as showing that the most important changes had an essentially local origin.

Anticipating for a moment this first conclusion, we can see at once that it poses more problems than it solves. If the existing account of Aegean developments is rejected, just how are we to explain the major changes that occurred? This is the central problem which has first to be faced, and it is treated here in very general terms, applicable equally to other civilisations at other times. A rough explanatory framework can be constructed to facilitate the survey, undertaken in Part II of this book after the presentation of the basic material in Part I.

One of the most striking features of culture is that it changes, and human behaviour changes, with respect to time. These changes occur, by comparison with those of organic evolution, very rapidly indeed. In this it differs from the behaviour of animals. For whereas a bird may build and decorate a nest, and claim proprietary rights over an area of territory—both extra-somatic adaptations, one material and one social—these behaviour patterns, like the dance language of the bees, are genetically determined. How culture has changed, and how it changes, is something the archaeologist seeks to explain.

Culture change and the growth of civilisation has been explained at different times in a wide variety of ways. The pattern of history is seen as the will of God (‘God is working his purpose out, as year succeeds to year: God is working his purpose out and the time is drawing near’). Or it is the expression of mans genius (‘We in the ages lying, in the buried dust of the earth, built Nineveh with our sighing, and Babel itself with our mirth.... We are the music-makers, and we are the makers of dreams’). Or again it is the product of the operation of laws of culture process. In the words of Auguste Comte (1875, 427), ‘this sociological recognition of laws perfects the concept of law in all other provinces.... The sense of the presence of invariable laws, which first arose in the mathematical province, is fully matured and developed in high philosophical speculation by which it is carried on to universality.’

Archaeology, and hence prehistory, certainly differs from history in declining to explain the past in terms of the thoughts of its actors. The refusal seems inevitable, since the actors of prehistory are not Individually identifiable. The material nature of the data of archaeology at first indeed suggests an exact analogy with the natural sciences, as Comte suggested, and the notion today attracts some archaeologists who, dissatisfied with the explanations so often given in archaeology, seek to make statements of a higher generality. The highest goal is sometimes set as the discovery of the ‘laws of culture process’ (Binford 1968a). Archaeology has, however, so far failed to formulate universal laws, and it seems unlikely that it will be able to do so. It seems at present doubtful whether the framework appropriate to the explanation of change in human culture will show a structure precisely the same as the hypothetico-deductive framework regarded by philosophers of science as sustaining the procedures of the physical sciences. Sir Karl Popper (1957, 120 f) has very cogently dismissed the notion of ‘law’ in history (and by implication, in prehistory), and until these persuasive objections can be overcome the implication that all archaeological explanations need aspire to the status of laws of culture process is difficult to accept.

Where the ‘culture process’ approach does advance our understanding considerably is by insisting that cultures (or civilisations) cannot be regarded as indivisible units. As Lewis Binford (1965, 203) has put it, ‘The normative theory of culture, widely held among archaeologists, is inadequate for the generation of fruitful explanatory hypotheses of cultural process. One obvious shortcoming of this theoretical position has been the development of archaeological systematics that have obviated any possibility of measuring multivariate phenomena and permit only the measurement of unspecified “cultural differences and similarities” as if these were univariate phenomena.’ The alternative is to lay emphasis rather on the different factors, or dimensions, or subsystems, of the culture (the terminology depending on the precise model which is being used) and the manner in which they interact, resulting in a change in the culture. By stressing the interrelationship of factors this approach avoids singling out one single aspect—climate, population, religion or whatever—as uniquely significant.

A consideration of culture process demands more than a simple narrative of events. For instance the statement that a pronounced change in the material culture of an area was preceded by a migration to it does not adequately explain the change (Binford 1968c, 267 f). Some more detailed analysis is needed to indicate the way in which the migration acted upon the existing society and its existing cultures. To speak of ‘culture influence’ resulting in ‘modification of the culture’ is vague: the same mode of thought leads to talk about the diffusion of culture ‘traits’ or the ‘influence’ of the German daggers, for instance, on the daggers of the British early bronze age as if these mere artefacts were living beings, each with a will of its own. But as Professor Hawkes rightly commented, ‘Battle axes don’t fly’, and to invest the artefacts or the culture itself with human attributes can be dangerous. Although we define a culture operationally as a ‘constantly recurring assemblage of artefacts’ its explanation cannot be restricted to the artefacts themselves.

While the simple narration of a sequence of events is not an explanation, it is a necessary preliminary. We are not obliged to reject Croce’s statement (quoted Collingwood 1946, 192): ‘History has only one duty: to narrate facts’, but simply to find it insufficient. The first, preliminary goal of an archaeological study must be to define the culture in question both in space and time. Only when the culture has been identified, defined and described is there any hope of ‘taking it apart’ to try to reach some understanding of how it came to have its own particular form. But the interest with space-time system-atics is never an end in itself: as Sir Mortimer Wheeler put it (1954, 215), ‘We have been preparing timetables, let us now have some trains.’

An explanation for change in prehistory seeks to give a deeper insight into prehistoric cultures than the simple narration of a culture sequence. On the other hand, we have expressed doubt as to whether it can aspire to the form of universal law seen in the natural sciences. Between the existence of historical narrative and scientific law lies the possibility of explaining how certain events came about by linking them to previous events and circumstances. To establish causal chains requires more than listing events: the continuity between them has to be established, and this does seem to require the formulation of meaningful generalisations which, while lacking the universality to which Popper rightly objects, do have some predictive power. The precise nature of such generalisations remains a crucial problem in archaeological and historical theory. Yet without claiming to solve this problem, one can at least begin to see a way around it. Changes in culture can meaningfully be explained in terms of the continuous operation off actors within the culture, which are continually inter-acting (Flannery 1967a, 119). This lies at the kernel of the notion of ‘culture process’.

The explanation then involves the choice of a mechanism, a notion of how these factors interact. It implies a view of the past, a framework into which to fit one’s ideas, in short a model (Renfrew 1968c). The framework or analogue model which will be adopted here is that of a culture viewed as a system.

The potential value of the systems approach as applied to human culture is enhanced by the rigour which the growth of cybernetics has brought to it. Norbert Wiener himself applied to human societies a basic concept of systems theory, that of homeostatic processes (1948, 187): ‘Small, closely-knit communities have a very considerable measure of homeostasis: and this whether they are highly literate communities in a civilised country, or villages of primitive savages. Strange and even repugnant as the customs of many barbarians may seem to us, they generally have a very definite homeostatic value which it is part of the function of anthropologists to interpret.’

Various properties of systems are very relevant to the study of cultures: systems as models have been discussed by Ashby (1956, 109). He makes the important observation that systems have ‘emergent’ properties when they are very large (as in the case of a culture) or when our knowledge of the behaviour of their components is otherwise incomplete. The essential point here is that a system, in the precise cybernetic sense, makes a particularly good description of, or model for, a human culture.

Systems behaviour has been extensively used also in considering the economic behaviour of societies, and it is particularly interesting that the early application here was independent of the development of electronics and cybernetics in relation to information theory, but arose through Tustin’s application of control-system engineering (Tustin 1953).

With so many evident possibilities it is perhaps surprising that not until 1965 was an equation made between cultures and systems, in this sense. Lewis Binford (1965, 203) then ‘proposed that a culture be viewed as a system composed of sub-systems ... differences and similarities between the different classes of archaeological remains reflect different sub-systems and, hence, may be expected to vary independently of each other in the normal operation of the system during change in the system.... In cultural systems, people, things and places are components in a field that consists of environmental sub-systems, and the locus of cultural process is in the dynamic articulations of these sub-systems’ To refer to culture systems, therefore, becomes more than a vague figure of speech: it indicates the use of a model, which, because of its great generality and flexibility, promises to be very valuable. David Clarke has usefully listed a number of properties of certain kinds of systems which can be applied to cultures (Clarke 1968, 75 f, 224 and 275).

Both Binford and Clarke, however, like Wiener before them, have simply indicated the possible usefulness of applying this model to archaeological cultures, without actually doing so. Kent Flannery was apparently the first to do this in his paper ‘Archaeological systems theory and early Mesoamerica’ (1968, 67). Very lucidly, and with the avoidance of unnecessary jargon, he analysed five food procurement systems in terms of two regulating mechanisms, seasonality and scheduling. And he examined six procurement systems in terms of positive feedback.

So far, such concepts have not explicitly been applied, or at any rate not in detail, to the origins of civilisation. Although the application presents difficulties, it seems to be worth trying. For, in the first place, it sets up a coherent model for society and for the interaction of its parts, which is much broader in its scope than an approach which begins and ends simply with artefacts and refuses to look beyond them, or which remains preoccupied with the complexities of space-time systematics. Human societies can only be understood in terms of human situations, even if all our knowledge about prehistoric ones has to come from artefacts, and all inferences about them have to be tested against the material record. Secondly the explanations to which this approach gives rise are hypotheses, which have specific implications, and which can be tested and in some cases refuted. The systems approach allows one to view specific situations in space and time as the outcome of complex interactions which operate continuously. To say this need not imply any rigorous or prescriptive determinism.

Operationally defined, a culture is a constantly recurring assemblage of artefacts. To represent the culture as a system or as part of a system, it is useful to consider not only the preserved artefacts, but the members of the society that produced them, the natural environment they inhabited and the other artefacts (including the nonmaterial ones such as language and projective systems) which they made or used. Obviously we cannot have detailed knowledge of all these for prehistoric societies, but it is proposed that we assume they existed. The artefacts available today, which we will take to be of known provenance and approximately known date, are the material remnant of this system.

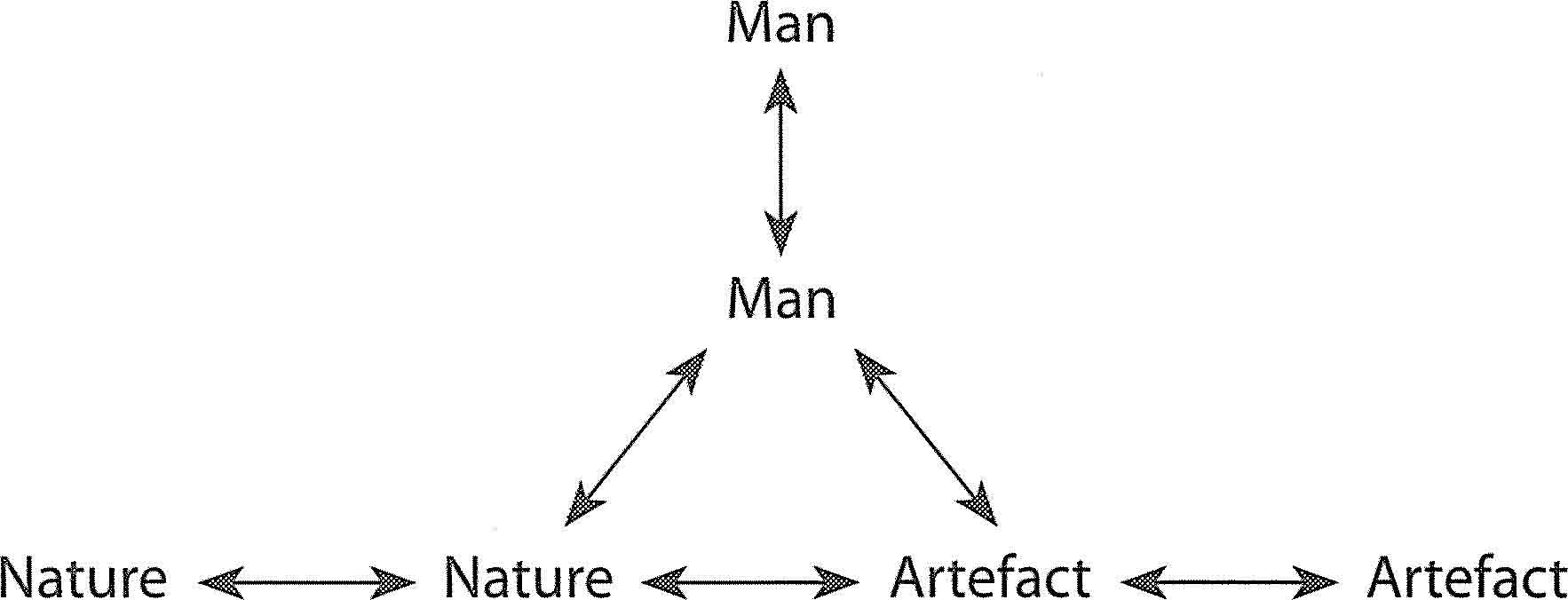

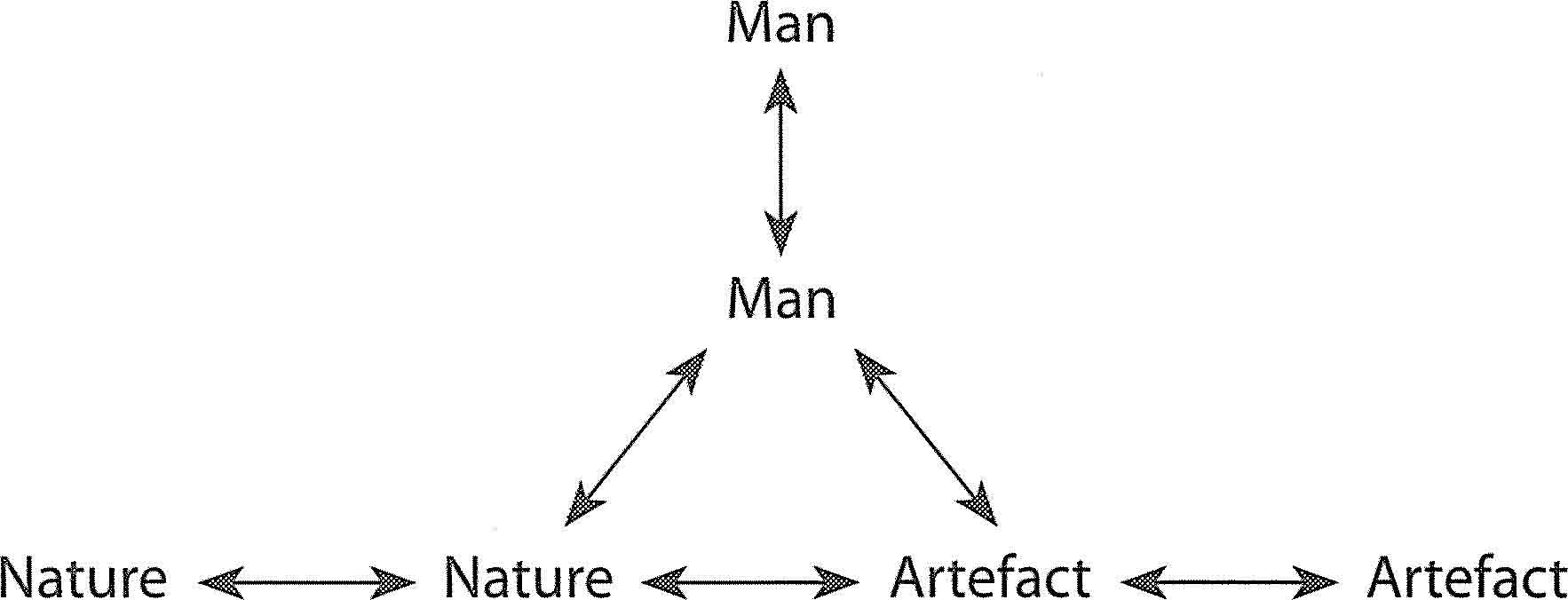

The components of the system are not only the members of the society but the artefacts which they have made or which they used (including the nonmaterial ones) and all objects in nature with which they come into contact. ‘Anything that consists of parts connected together will be called a system’ (Beer 1959, 8). What connects the components of this particular (and very large) system are the actions between these three classes of individual: man, artefact, natural object. As Katz and Kahn (1966, 94) have written: ‘The problem of structure, or the relatedness of parts, can be observed directly in some physical arrangement of things where the larger unit is physically bounded and its sub-parts are also bounded within the larger structures. But how do we deal with social structures where physical boundaries in this sense do not exist? ... The structure is to be found in an interrelated set of events. It is events rather than things which are structured, so that social structure is a dynamic rather than a static concept.’

FIG 2.1 Six kinds of interaction, five of them within the culture system, and one (Nature/Nature) outside it.

The dichotomy here established between man and nature does not support in any sense the view that man is not just an integral part of the natural world, inextricably bound with it. Indeed the whole purpose of utilising the systems approach is to emphasise man – environment interrelations, while at the same time admitting that many fundamental changes in man’s environment are produced by man himself. They emerge, that is to say, from technological and social changes rather than simply from ecological ones.

Artefact-artefact interactions can come about without the direct presence of man: when the new wine cracks the old bottle, or when the domesticated cow eats the domesticated wheat. Nature-nature relationships (referring to natural phenomena) are relevant too: the cow needs grass, the fisherman fish and both the grass and the fish may be beyond the field of man and his artefacts. The overall system which we have to consider, therefore, is larger than man’s culture, in that it includes both his environment and man himself.

It is important to realise that the choice of elements which constitute the system is ours. We are free to define the interacting elements which constitute the system. When there are other elements not defined as part of a system, which interact with It, then the system can be said to have input and output: it is an open system.

There are two important points to consider: the boundaries of the system, and the nature of the connections within the system. First, it should be noted, a system can be simplified and portrayed in a new form when its states are compounded suitably: ‘Were the engineer to treat bridge-building by consideration of every atom, he would find the task impossible by its very size. He therefore ignores the fact that his girders and blocks are really composite, made of atoms, and treats them as his units.... It will be seen, therefore, that the method of studying very large systems by studying only carefully selected aspects of them Is simply what is always done in practice’ (Ashby 1956, 107). It would be possible, therefore, to consider the atomic and molecular structure of the objects and artefacts, regarding each as a system in itself. Equally the humans participating can each be regarded as a system. For the present purpose, however, these natural objects, artefacts and people are our components.

Just as it is convenient to ignore individual atoms and generalise on a higher level, so it can be convenient to lump together these components, and speak of larger units. When these larger units themselves are structured we may designate them as subsystems.

In order to establish the nature of the boundary of the culture, the man-environment system of the given culture can be described In terms of the individual settlement units as distributed in space. No settlement in the Old World is completely isolated from any other: we can imagine the situation, say 5,000 years ago, when each village had at least some contact with its immediate neighbours, they with their neighbours, and so on, creating a great lattice across the whole of Europe and indeed Asia, and only stopping perhaps at the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. ‘No man is an island unto himself, each is a peninsula, a part of the Main.’

In deciding on the spatial boundaries of our system we are thus ‘making a somewhat arbitrary decision—as we are entitled to do. As archaeologists we follow the record of the artefacts as discussed in the last chapter. The archaeologist considers the distribution of artefact types, and sets the boundaries of the archaeological culture according to convenient criteria. We follow these, and indeed assume that the uniformity within the culture area is due to the contacts and inter-connections described. The greater difference with the outside region is generally assumed to be due to diminished contacts and interrelations.

For different purposes we shall draw the boundaries differently: at one moment we may wish to consider the Minoan civilisation, perhaps in the seventeenth century BC, and will draw the boundaries accordingly at the next we may refer to the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation (say of the fourteenth century BC). Criteria of different degrees of uniformity will lead to the definition of larger or smaller units.

We should note too that with the passage of time the elements of the system are changed: people die and are bom, artefacts are made and discarded. As von Bertalanffy says of organic systems (1950, 155): ‘It is the basic characteristic of every organic system that it maintains itself in a state of perpetual change of its components. This we find at all levels of biological organisation. In the cell there is a perpetual destruction of its building materials through which it endures as a whole.... In the multicellular organism, cells are dying and are replaced by new ones, but it maintains itself as a whole. In the biocoenosis and the species, individuals die and others are born. Thus, every organic system appears stationary if considered from a certain point of view. But what seems to be a persistent entity on a certain level is maintained, in fact, by a perpetual change, building up and breaking down of systems of the next lower order: of chemical compounds in the cell, of cells in the multicellular organism, of individuals in ecological systems.’ No one is saying here, of course, that a cultural system can be equated with an organic system: but it does share certain properties with them, and with Heracleitus’s river: ‘A man never bathes in the same river twice.’

Our culture system is also of great complexity because of the nature of its interconnections. Already in talking, say of trading connections alone, it can be broken down info subsystems. Each single settlement unit can itself be regarded as a subsidiary trading subsystem, and they articulate together to form the overall trading subsystem. The division into subsidiary subsystems here is a spatial one, and can be represented in the dimensions of space.

But the elements of our system are not only linked by connections between localities, such as those of trade. The man-artefact-natural object connections provide food and shelter for men, the man-artefact connections involve the manufacture and use of all manner of things, the man-man connections involve kin relationships, and other social relationships and conventions. This is the consequence of the multidimensionality of man’s environment, as discussed above in chapter 1.

We can regard the men in society as nodes in a lattice connected in numerous different ways, each way corresponding to one of the various dimensions of the environment.

In defining subsystems in the culture corresponding to each of these types of connections (and to each of these dimensions) we are not dividing the society spatially but simply following different kinds of networks: ‘It must be noted that in a real system the “diagram of internal connections” is not unique. The radio set, for instance, has one diagram of connections if considered electrically, and another if considered mechanically. An insulator, in fact, is just such a component as will give firm mechanical connection while giving no electrical connection. Which pattern of connections will be found depends on which set of inputs and outputs is used’ (Ashby 1956, 92). In the same way we may picture the incredible complexity of a cultural system, acting in several dimensions and with several different kinds of connections between its components which are itself of several different kinds. In the culture system we are free to define the subsystems. As Wolf has written (1967, 449): ‘We may regard civilisations as social sets, in which the elements are linked together in a large variety of ways and with different degrees of cohesion. Methodologically this means that we do not have to account for all the elements—only for those which we hold to be significant. When considering civilisation the possible choice is almost infinite.’

For our purposes the following subsystems may be distinguished (see fig. 21.1).

The interactions which define this system are actions relating to the distribution of food resources. Man and the food resources and the food units themselves are components of the subsystem which are interrelated by these specifically subsistence-oriented activities (see Ch. 15).

This subsystem is defined by the activities of man which result in the production of material artefacts. The components are the men, the material resources, and the finished artefacts (see Ch. 16 and 17).

This is a system of behaviour patterns, where the defining activities are those which take place between men. It is not possible to distinguish clearly all the activities of the subsistence and technological subsystems from those of the social subsystem, but the essential point in the latter is that we are no longer looking at activities under their aspect of food production, or of craft production, but looking at them as patterned inter-personal behaviour. It would be possible here to distinguish an economic subsystem from the social subsystem, but it is probably simpler in a non-market society to look at the accumulation of wealth as a social phenomenon at least as much as it is an economic one (see Ch. 18).

Here, we are speaking of all those activities, notably religion, art, language and science, by which man expresses his knowledge, feelings, or beliefs about his relationship with the world. The social system itself may involve activities that are expressive of relationships in this way, that are symbolic of relationships between human beings. Making obeisance before the throne of the ruler would be one of these. But we are defining such expressions between men as belonging within the sphere of the social subsystem. The projective systems, in other words, are those in which man gives formal expression to his understanding of and reactions to the world. His thoughts and feelings are expressed, that is to say projected, and given symbolic form whether in language or in worship, in the production of written records or of works of art, including music, dance and other abstract forms amongst those of more explicit meaning (see Ch. 19).

This is defined by all those activities by which information or material goods are transferred between human settlements or over considerable distances. The activities here are all those which involve travel, for any of the components of the system whether men of artefacts (see Ch. 20).

The boundaries between these systems are extremely difficult to define, since a given human action can exist in several dimensions at once. The construction of a temple, for instance, an action of considerable complexity, lies in the first place, in its conception, in the field of the projective systems. It will also involve economic activities. The builders will have to be fed, which belongs in the field of subsistence, and, of course, they will be organised in a manner governed by the social subsystem. This is inevitable since many human actions have a meaning at several levels, with undertones and overtones. And, as we shall see in the next chapter, it is the complex interconnectedness of the subsystems which gives human culture its unique potential for growth.

These are the subsystems whose functioning must be isolated if we are to reach an understanding of growth and change in the culture. In Part II of the present work the growth and development of metallurgy is also given special consideration (in chapter 16) since it was obviously of central importance in the third millennium Aegean, although in more general terms metallurgy is simply one aspect of craft technology. Population, which is a basic parameter of society rather than one of its subsystems, is discussed first, in chapter 14, since population increase in the Aegean, as in most early civilisations, was one of the most significant and relevant developments. These are the terms in which the life of the third millennium bc in the Aegean will be examined.

In a culture which is not changing, the various subsystems are in a state of equilibrium (or, in more specialised jargon, of quasi-stationary equilibrium). There is continuous activity: food is grown and eaten, buildings collapse and are repaired, imports and exports are produced and consumed, social relationships are observed, religious services are held. This year, next year, the ‘same’ things happen: people are born, married, die but nothing is new. This is the working of habit and convention. Hawkes (1954, 155) has emphasised this consistency in the norms of human behaviour. ‘The human activity which (archaeology) can apprehend conforms to a series of norms, which can be aggregated under the name of culture.... The notion of norms in mans activity ... is an anthropological generalisation based on the extensive degree of conservatism shown by primitive man in his technological traditions.... Without this the whole subject would crumple up.’ We are all creatures of habit, otherwise we could not face the alarming multiplicity of ‘new’ problems which would arise. As Samuel Beckett has said, ‘L’habitude est une grande sourdine.’

But, of course, the system is not so stable as this: fluctuations in the natural environment alter the equilibrium. Fishing is poor and there are less fish to eat: there are more births than usual and more mouths to feed: it is a wet summer and the roofs leak: an eclipse of the sun is seen as a dread portent. And then there may be ‘input’ from right outside the system: military attack from another culture, for instance. Or innovations within it: a new tool is invented, or there is dissatisfaction with the conduct of the chief. The remarkable thing is that in every case each subsystem acts homeostatically, to counteract the disturbance. In the subsistence system the level of food is stabilised either by greater investment in fishing, or by switching to other foods. In the utility subsystem roofs are repaired. In the religious system appropriate steps are taken to counteract the alarming disturbance. Military attack is opposed, the new tool replaces the old, the chief takes measures to enhance his authority. Each of the subsystems of the culture is acting like a stabilised or regulated system, in the cybernetic sense. Their variables (food level in the subsistence system, population in the demographic situation, integrity in the defence system, social behaviour in the social system, belief behaviour in the religious system) are kept within assigned limits, as is necessary for survival (Ashby 1956, 197). The behaviour of the culture (and doubtless the artefacts which the archaeologists will recover from it) is essentially unchanged. Various interesting consequences flow from this, for example the need for variety in the culture to oppose undesirable variety outside it (Ashby 1956, 206 f).

Indeed each subsystem can be so regarded as self-regulating. And the different dimensions of life can be considered independently. But at the same time we must remember that in the culture system the component subsystems do not vary independently, they are coupled. This is, of course, simply a statement of anthropological functionalism, that different aspects of a culture are all interrelated. It does not mean, however, that changes in one subsystem must necessarily produce changes in all the others.

The equilibrium in a subsystem of the culture is achieved by automatic regulation which acts, like Le Châtelier’s principle: ‘If a system is in stable equilibrium and one of the conditions is changed, the equilibrium shifts in such a way as to restore the original conditions’. It operates by means of negative feedback: the ability to meet an effect by operating in such a way as to oppose it and thus minimise change. If the food resources of the society suffer a setback (a poor harvest for instance), the society acts in such a way as to restore the level of food supply, for example by trade, and thus to minimise the disturbance. The system acts to counter the disturbing force, so that the feedback is negative.

All this, then, gives us some understanding of the essential coherence and conservatism of all cultures: the behaviour patterns in one generation are communicated to the next generation: the society’s ‘adjustment’ or ‘adaptation’ to its natural environment is maintained: difficulties and hardships are overcome. Minor changes may be brought about through ineffectiveness in this communication: the pottery decoration of a daughter may differ a little from that of her mother. But this is merely a ‘random drift’ which does not in itself have a significant effect on the life of the society. Only if the outside disturbance is so great that the homeostatic controls cannot overcome it, is the life pattern disrupted. ‘When a system’s negative feedback discontinues, its steady state vanishes, and at the same time its boundary disappears, and the system terminates’ (Miller, quoted Katz and Kahn 1966, 96).

Thus, a military attack will be resisted by the society. But if it cannot be overcome, it may well produce a disturbance beyond the limits of tolerance of the system: the system breaks down. Or natural environmental forces may produce a serious disturbance: the increasing salinity of the soil of Mesopotamia was a disturbance which the inhabitants of the Sumerian heartland strove to overcome (Jacobsen and Adams 1958). A similar theory, involving progressive flooding and silting, has been used to account for the decline of the Indus civilisation (Raikes 1965). And the eruption of the volcanic island of Thera certainly brought a total end to the human system occupying that island just as that of Vesuvius to Pompeii. It has even been suggested that the disturbance produced by this eruption was so strong as to exceed the homeostatic controls of the entire Minoan system in Crete and to bring about its disintegration.

In all this the culture system is acting negatively, passively almost, simply acting to regulate outside events. While the negative feedback picture is effective, then, in illuminating the stability and conservatism of the society, it does not explain how society will ever change, except through an outside challenge. It is limited to the Toynbee concept of cultural response to natural environmental challenge.

The systems approach does offer also a convenient model for growth, for change occurring within a society. Negative feedback itself is never a sufficient explanation for cultural development, for how culture came into being, but merely for how an existing order was modified through external change. Change, progressive change, can however be considered in terms of deviation-amplifying mutual causal systems. ‘Such systems are ubiquitous: accumulations of capital in industry, the evolution of living organisms, the rise of culture of various types, the inter-personal processes which produce mental illness, international conflicts, and the processes which are loosely termed “vicious circles” and “compound interest”, in short all processes of mutual causal relationship that amplify an insignificant or accidental kick, build up deviation and diverge from an initial condition’ (Maruyama 1963, 164).

Kent Flannery (1968, 80) has described such a positive feedback system which operated in the system of wild grain procurement in early Mesoamerica and resulted both in the selection for genotypes of the domesticated maize and in the development of food production. As he well says: ‘The use of a cybernetics model to explain prehistoric cultural change, while terminologically cumbersome, has certain advantages. For one thing it does not attribute cultural evolution to “discrepancies”, “inventions”, “experiments” or “genius”, but instead enables us to treat prehistoric cultures as systems. It stimulates enquiry into the mechanisms that counteract change or amplify it, which ultimately tells us something about the nature of adaptation. Most importantly, it allows us to view change not as something arising de novo, but in terms of quite minor deviations in one overall part of a previously existing system, that once set in motion can expand greatly because of positive feedback.’

A culture, as we have seen, may be considered as composed of coupled systems, and the nature of their coupling is very relevant here and has to be considered. Its stability and growth is determined by the behaviour of these systems-in which human beings participate, of course, and human ideas, so that the growth is not ‘determined’ in a materialist sense. As Maruyama has written (1963, 178): ‘Sometimes one may wonder how a culture, which is quite different from its neighbouring cultures, has ever developed on a geographical background which does not seem to be in any degree different from the geographical conditions of its neighbours. Most likely such a culture has developed first by a deviation-amplifying mutual causal process, and has later attained its own equilibrium when the deviation-counteracting components have become predominant, and is currently maintaining its uniqueness in spite of the similarity of its geographical conditions to those of its neighbours’

This, then, is the growth process which we are seeking to analyse and which can be discussed with the minimum of jargon, although terms such as positive feedback and negative feedback are necessary. In the next chapter an attempt is made to look more carefully at the precise conditions which may give rise to growth, and not only to growth in size but to fundamental changes in the structure of culture, leading ultimately to the emergence of civilisation.