The changes in craft technology and production during the Aegean bronze age transformed the physical environment of man. He lived now, more than before, in a world of artefacts of his own making, which insulated him to a considerable extent from the world of nature, and protected him from its extremes of cold, of hunger and of fear which his palaeolithic ancestors must have suffered.

The environment of man is multi-dimensional, and in chapter 2 the significance of the social world, of the relationships of a man with other humans, was stressed. There are clear indications that this too was becoming more complex. Indeed, if the institutions and regularised customs of society be viewed as artefacts—and they are indeed products of man—they can be seen to fulfil functions broadly analogous to those of the material artefacts which mediate between man and the material world of nature. The social systems regularised and established patterns of conduct among men, bringing order to a man’s social environment and offering protection against its potential dangers, lack of cooperation and hostilities.

The craft specialisation which was, as discussed in chapter 17, emerging during the third millennium was more widely significant than in the field of technology alone. It produced not merely a few new roles and occupations, but a whole new field of roles, and the very concept of occupation itself. Previously a man must have had a restricted variety of roles to play—in his family, as a member of a simple village society, and so forth. Now it became possible in addition for him to be a smith, or to be a potter, or to be a craftsman in stone. This was, literally, a new kind of being, to enjoy the status of a skilled craftsman and to be known, probably, by this role—just as is the modern doctor or village policeman. Previously, perhaps, a man had been known either by his position in a kinship system—as such-and-such a relation to a clan leader—or by the lands he occupied and tilled. To these primitive concepts of kinship and of territory a third was added: professional occupation.

Some aspects of the social order in the prehistoric Aegean are very difficult to reconstruct. The kinship system, for instance, has left little direct trace in the archaeological record, and can only be guessed at by comparing modern ethnographic parallels (comparisons sometimes misleadingly termed ‘hypotheses’) with such oblique indications as are available (‘testing the hypotheses’). Other systems have left positive evidence and we can discuss the development of hierarchy, of wealth, of redistribution systems, of warfare, and of settlement size and function. First, however, it seems possible to indicate the general nature of Minoan-Mycenaean society and to suggest how it may be described in terms of anthropological theory—although admittedly this is but a single remove from the use of a specific parallel from ethnology

Minoan-Mycenaean society can be viewed, in social terms, as composed of a number of large chiefdoms or principalities. This idea is put forward in the next section. The evidence bearing on the prehistoric Aegean social systems is then reviewed, and finally it is argued that during the third millennium we see both the completion of the evolution from tribe to chiefdom, and the beginning of that from chiefdom to principality.

Anthropologists frequently speak of three levels of social organisation in prehistoric times. Bands are conceived as assemblages of nuclear families, foragers for wild food, sometimes perhaps hunting together, often simply as family units, and integrated above the level of residence units only by individual kinship alliances (cf. Steward 1955, 122 f.; Service 1968, 7). The band level of integration must have been a characteristic form of social organisation during much of the palaeolithic era; it corresponds to what an earlier generation of anthropologists termed ‘savagery’ (Morgan 1871). Typical tribal societies are also often simple, fairly small, independent, self-contained and homogeneous, but they are usually considerably larger than bands (cf. Sahlins 1968). They normally include a number of fixed residence units or villages.

Tribal society is typically associated with food production, and the kinship segments or families are tied, much more firmly than in bands, by pan-tribal associations or sodalities, including some based on lineage and others which are not determined by kinship, such as age-grade associations, secret societies, or warrior fraternities. But the basic tribal structure is a weak one: there is no governmental organisation at tribal level and leadership is often confined in scope to the primary community, the village. This stage in social evolution was termed by Morgan ‘barbarism’, and it has plausibly been suggested that many neolithic cultures may be regarded as tribal societies.

The third major stage in social development, in the classification widely used by social anthropologists, is the state, a community of larger size, with agencies of government which, unlike those of the tribe, are explicit, complex and formal (Krader 1968). The organisation operates to secure the internal peace of society, to protect its external borders, and to pursue foreign relations with other states. This is the level of organisation generally equated with ‘civilisation’, and with which one might wish at first sight to link the Minoan and Mycenaean palace organisations and territories.

As we shall see, however, none of these terms is entirely appropriate to the civilisation of the late bronze age Aegean, which, while clearly organised on a basis more complex than the usual tribal level, lacked, none the less, some of the features of the developed state. A further model for the organisation of society seems illuminating here. It is in some ways intermediate between ‘tribe’ and ‘state’—the chiefdom. Service has usefully re-defined the term chiefdom as a society distinguished from the tribal ‘by the presence of centres which co-ordinate economic, social and religious activities.... Specialisation in production and redistribution of produce occurs sporadically and ephemerally in both bands and tribes. The great change in chiefdom level is that specialisation and redistribution are no longer merely adjunctive to a few particular endeavours but continuously characterise a large part of the activity of the society. Chiefdoms are redistributional societies with a permanent central agency of co-ordination. Thus the central agency comes to have not only a economic role—however basic this factor in the origin of this type of society—but also serves additional functions which are social, political and religious’ (1962, 143 f.).

In his discussion of this term, Service stresses several features common to chiefdoms. The defining one, of course, is the office of chief, which implies the existence of specific functions and privileges, as well as a definite form of succession. These rules and sanctions relating to the state of chief may involve food, personal conduct and ritual activities, comprising both taboos and prescriptions. The most visible of these is generally a distinctiveness in dress and ornamentation. The succession is generally by primogeniture. The second social feature is a salient personal individual ranking: chiefdoms are hierarchical, with the higher members of the hierarchy generally related by kin to the chief and constituting a nobility. In this sense this is a class society, although without the existence of clear, separate, economically distinguished ‘classes’. The society is, rather, graded internally like a feudal aristocratic class, but with no mass of peasants underneath. (This is a point to be considered again when deciding whether the Mycenaean society might not, after all, better be described as a state.) The sociopolitical ordering is created and perpetuated by a whole series of proscriptions, marriage customs and genealogical concepts, which can barely be discerned in the archaeological record, and which in turn influence social structure, status terminology and etiquette behaviour.

Chiefdoms show generally both an increase in the population density of the society as a whole, and often also an increase in the size of individual residential groups.

One of the most striking things about the evolution of culture is the rapid improvement in the products of craft specialisation at the point of the rise of chiefdoms (ibid., 148). The specialised crafts are often subsidised at the redistributional centre, and this may result in the specialisation of a family line: the job becomes hereditary and the work increasingly skilled. The related aspect is the potential which chiefdoms offer for the development of public labour, and hence the accomplishment of works, such as irrigation or the terracing of slopes, or the erection of monuments such as temples or pyramids, generally beyond the scope of a tribal organisation.

Religion takes new forms, often with a priesthood which now occupies a permanent place in society. Supernatural beings come to include ancestors in genealogical rank-order, reflecting social order. Feuding within the society is much diminished, but warfare between societies was probably an important condition for the rise of chiefs, and the chief is also a military leader. Chiefdoms have borders or boundaries, and the ‘rise and fall’ of chiefdoms, often a result of conflict over territorial questions, is so frequent a phenomenon that it seems part of their nature.

This concept, although not necessarily everywhere applicable, is a useful adjunct to those of state and tribe. At once it is obvious that many of the most characteristic features of the chiefdom are seen in the Aegean for the first time during the early bronze age, and still more clearly in the palace civilisations. Armed with these a priori concepts (a priori insofar as the Aegean is concerned) we can now look at some of the salient features of the Aegean development.

The archaeological record reveals only limited information about social organisation in Greece in neolithic times. Two archaeological units are recognisable: the settlement and the culture.

The settlement is a village, which in north Greece consists of separate houses, each presumably the home of a family unit. Nea Nikomedeia gives the clearest picture of the internal arrangement of such villages (Redden 1962; 1965), although no complete plan is available from Greece. Romanian and Bulgarian settlements of the fourth millennium Gumelnitsa culture (fig. 5.1) suggest how such a village may have looked. There is little evidence for social differentiation—although a single large building was found at Nea Nikomedeia containing some splendid stone axes and figurines. It may have been a tribal meeting house or even the residence of some special personage.

These villages were set within a few kilometres of each other. No area of Greece has been exhaustively surveyed for prehistoric sites, but the Plain of Drama, at phase II of the Sitagroi sequence, gives some indications of the settlement pattern. Villages were sited in such a way that the best arable land was exploited. At this time situations were preferred which offered easy access to a range of environments, so that a favourite location was on the edge of good arable land.

The modern archaeologist tends, perhaps unconsciously, to compare the social structure of such villages with the social pattern of villages in the same area today, whose economy was, until the introduction of tobacco, cotton and maize, rather similar in its essentials. He may at first think of them as peasant communities, without any evident tribal structure serving to relate one village to another. But this is, of course, to ignore that peasants today belong to states, are linked economically (through marketing) to the state organisation, and participate in a state religion (Wolf 1966, 2). As Redfield (1947) has clearly shown, the folk culture of peasants presupposes the existence of a ‘higher’ civic culture, so that we must consider seriously whether these seemingly independent, autonomous villages were not in fact closely related, unlike the peasant villages in the same area today, by close social links of a tribal nature.

The archaeologist recognises that adjacent villages share the same culture—use the same artefacts assemblages, decorate their pots in the same way. Distribution maps can be plotted of artefact types, and ‘cultural borders’ drawn and culture areas defined on this basis. It is, of course, tempting to equate these with tribal areas. But culture distributions are constructs of the archaeologist, and can be plotted in very different ways to obtain entirely different results. Moreover, ethnographic parallels show that while a given tribe will usually have a fairly standard tool-kit for each of its various functions, the same artefact assemblages may be shared by other tribes also (Clarke 1968, 365 ff.). The territory of a single tribe is thus not likely to be larger than the distribution of an archaeological culture, but it may be very much smaller.

The recognition of tribes in prehistoric Aegean society, and a fortiori the definition of tribal areas, is thus very much the imposition of an a priori anthropological model upon the material. Steward (1955, 44 and 53) has stigmatised the term ‘tribal society’ as an ‘il-defined catchall’, and in dealing with neolithic Greece we must remember that the modern tribal societies of the world are 6,000 years more recent than those of which we are speaking, and new social forms may have developed during this period. A hint of this perhaps given by the apparent absence of weapons of war in the Aegean neolithic—we find only a few slingstones—for local warfare and skirmishing Is today a common feature of many tribal societies. But there may, of course, have been other weapons of wood.

The archaeological unit ‘culture’ cannot be translated automatically into tribal terms: it is necessary to consider first what such an equation implies. The basic archaeological reality is the village farming settlement. These may have been linked to form segmentary tribes but, until we have positive evidence for pan-tribal sodalities, the suggestion is somewhat speculative. The artefacts and especially the ceramic decoration may yet hold information bearing on inter-village social links, but much more work has to be undertaken on the nature of these links. Their assumption seems a plausible way of explaining the homogeneity seen within a given culture, but it is supported by little concrete evidence. Their elucidation remains a task for the future.

The archaeological remains of the late bronze age give much more evidence of a social nature than do those of neolithic times.

First there are the palaces, obviously the homes of rich and powerful rulers whom one might well term ‘kings’. But any modern term carries with it overtones (here for instance of succession by a primogeniture in the male line). The meaning of the social terms used in the Linear B tablets can be established only by their context, which is not unequivocal, so that here these rulers will for convenience be termed ‘princes’ and their domains ‘principalities’ in the hope that these terms have less precise connotations than king and kingdom. We shall return below to the nature of these principalities.

Secondly we see throughout southern Greece in the late bronze age a fairly uniform culture (as defined by the artefacts) which covers the territories of several palace centres. There is a distinct but equally uniform culture in Crete in the Late Minoan I and II periods. Only in the Late Minoan III period is it more similar to that of Mycenae, so that some writers speak of a Mycenaean koine throughout the southern Aegean. Many however, would still distinguish sharply between the culture of Crete and of the mainland (Hooker 1969, 65).

A first question which we should consider in assessing late bronze age social organisation is whether there was ever a Minoan or Mycenaean ‘empire’ of the kind associated with some of the civilisations of the Near East. Few archaeologists would now hold that Crete ever held political control over mainland Greece: the Theseus legend is more suggestive in its story of the destruction of Knossos than in the tributary status of Athens with respect to Crete. Although the Mycenaean influence in Crete in the Late Minoan III period is so strong that some writers talk of a Mycenaean dynasty at Knossos, there is no indication of any actual political control from the mainland: the Knossos tablets have not been interpreted in this sense. If there was a Mycenaean conquest of Knossos, this may be seen as part of the normal ‘rise and fall of chiefdoms’, one of the ‘cyclical conquests’ of which Steward writes (1955, 196), and the ruler of Crete was not merely the agent of a mainland king.

It does, however, seem entirely possible that some of the islands were controlled, first by Cretan and then by Mycenaean chiefdom-states. Although the importance of the ‘thalassocracy of Minos’ may have been exaggerated (Starr 1955; cf. Buck 1962), there were certainly settlements on a number of islands, including Kythera, Thera, Kea, Melos and Rhodes, which imported large quantities of Minoan pottery in Late Minoan I times. These are the so-called ‘colonies’, and at most of them Minoan influence was followed by Mycenaean in the Late Helladic III period. Yet while Minoan influence on the islands was at its height, there were several flourishing palace centres in Crete, and it has not been shown that Knossos controlled the island politically at this time. Crete itself was probably not a single political unit. It remains doubtful whether the island ‘colonies’ were ever under any effective political control from Crete or mainland Greece.

In discussing territorial questions of the kind raised by the term ‘empire’, the geography of the Aegean is a dominant factor, as historians and geographers have realised (Myres 1953; Semple 1932). In classical times the Aegean saw the emergence of the city-state: tiny geographical units (the islands of Amorgos and Kea both supported three) which possessed none the less many of the defining features of states. The small size of the classical Greek city-state is well brought out by Plato’s ideal formulation whereby the state’s land should be divided into 5,040 allotments, to be owned by family heads, who were citizens (Laws v, 738A). This would suggest a total citizen population of 20,000, and an overall population (including slaves) of perhaps only 40,000 for the entire state. The difficulties of land transport in southern Greece, and the size of the islands made inevitable the kind of regional division which we see clearly in Mycenaean times also. It was not until the fifth century BC that Athens and Sparta, and later Macedonia, expanded their effective political control to form nation states or empires, so that we need not feel the absence of such an empire in earlier times surprising.

Nor does the existence of a fairly uniform Mycenaean culture in mainland Greece necessarily indicate a single Mycenaean state. Perhaps unconsciously following Homer (who must not, of course, be taken unquestioningly as a guide to Mycenaean social structure) we tend to think of a regional breakdown into principalities—Agamemnon ruling at Mycenae, Menelaus at Sparta, Nestor at Pylos, Odysseus at Ithaca, and so forth. These Homeric indications do seem to conform broadly to the archaeological pattern of the palace centres. A similar pattern may be imagined for Crete, with its large and possibly autonomous centres at Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia and so on.

If the effective political unit was the minor state or principality, it is difficult to grasp the underlying social structure which sustained the Mycenaean koine throughout southern mainland Greece, and later in some of the islands as well. If we follow Homer, its distribution corresponds to that of the Achaeans, who spoke the Greek language and thought of themselves as different from other people. They were linked by ties of kinship and friendship. They exchanged gifts, and in time of war could act together. And yet collectively they had no real organised structure of leadership. We may indeed speak of pan-Achaean sodalities linking the principalities, which were the basic organisational units, and operating between the princes who were their rulers. Thus the analogy for the Achaean-Mycenaean koine is the anthropologists concept of the tribe, whose residence units (or sub-tribes?) correspond to the principalities. There was certainly no single Achaean state, in the anthropologists sense, if we follow Homer.

Returning now to the Minoan and Mycenaean principalities themselves, it is clear from the Linear B tablets that they had an economic organisation which rivalled in complexity that of the Near Eastern states. Finley, one of the few to have considered the Minoan texts in social terms against the instructive background of other early societies rather than exclusively from a close reading and philological interpretation of the tablets, has drawn this conclusion. For him the tablets ‘help free “Asiatic society” from its traditional links both with the “Orient” and the inundated river valleys’ (1957, 144). The tablets give a clear picture of effective economic organisation, with their rations and especially their work quotas. And if the view be accepted that the Pylos tablets contain detailed logistic arrangements for territorial defence (Palmer 1963, 103 and 147) they also document some very impressive military organisation. There was nothing ad hoc about Mycenaean administration.

In other respects, however, the analogy with the state is less sure. The Minoan or Mycenaean prince did not preside over social or religious institutions so sophisticated as those of Hammurabi of Babylon or the Egyptian pharaoh. Minoan-Mycenaean society lacked, indeed, many of the features common to these early states. There are no great public or civic monuments, such as the statues of the pharaohs or the stelai of the Sumerians, and no great ceremonial centres like the acropoleis of the Greek city states or the pyramids and ziggurats of the early kingdoms. The citadels and palaces, and the tombs of their occupants, are the only great monuments of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation.

Nor is it yet clear to what extent there was in Minoan-Mycenaean society a well-defined class structure, although the Linear B tablets are felt by some scholars to document slavery.

Efficient political control is one of the criteria for the state: ‘the presence of that special form of control, the consistent threat of force by a body of persons legitimately constituted to use it’ (Service 1962, 171). The state constitutes itself legally, making explicit the manner and circumstances of its use of force, and forbidding other use of force, by lawfully interfering in disputes between individuals. Yet if we were to follow Homer, we should certainly deny to the Mycenaeans any effective form of overall state organisation. The assemblies which the Achaean leaders loved to call together did not apparently have very well-defined powers, although in a sense they were a limitation upon the individual power of the principal Greek leaders. Nor was the established assembly in Ithaca, which met in a prescribed place, an effective executive body. Odysseus had, upon his return, to fight to put his own house in order. On the other hand the efficiency of the Mycenaean palace economy suggests that Homers view of Mycenaean society is not a reliable one in this respect, and perhaps it should be discounted.

The small territorial size, absence of a clearly defined class structure and the suggestive lack of monumental religious or public buildings could indeed lead us to deny these principalities the status of state. Indeed Service’s concept of chiefdom would in some respects be an appropriate one to describe the late bronze age society of the Aegean. With their craft specialisation, their redistributional system, and their developed but not yet highly institutionalised religion (see chapter 19) there is an obvious analogy. But to draw this analogy is to overlook the significance of the palace as an institution. The economic organisation was institutionalised, and the tholos tombs and palace throne suggest that so too was the leadership. We shall see below that the term chiefdom can more conveniently be applied to the early bronze age Aegean.

In the last analysis these autonomous principalities did not differ in size from the Greek city-states, although as Finley rightly stresses they were societies of a very different nature (1957, 140). And with their palaces, technical accomplishments and writing they oblige us to regard the culture of the time as civilisation. Something more than chiefdoms, something less than states, their designation is not particularly important so long as their essential nature is clear, and so long as the terms used do not carry with them misleading overtones from other societies.

The palace principalities can thus be regarded as minor states, effectively organised economically, but in other respects not differing so strikingly from chiefdoms. At the same time they were linked to each other by affinities of culture and language, and by ties which probably did not amount to political organisation. These ties, as we have seen, are rather like tribal ties, and may indeed be the perpetuation of tribal links seen during the neolithic period between the different settlement units of a culture. There need be no contradiction here in seeing tribal links co-existing with an organisation at the level of minor states, since the anthropologist’s evolutionary scheme, from band to tribe and so to chiefdom and state, is no more than a construct. Taking the view that the Minoan-Mycenaean social organisation in the late bronze age was one of minor states or principalities, linked by ties resembling those operating within tribes, we can now proceed to consider the early stages of its development.

There are many kinds of hierarchy, but the most significant is that of power, the quality which ensures that one’s wishes are followed. The pecking order of statuses in the power hierarchy is often simply a chain of command. But in many societies wealth brings power, or power brings wealth, so that the power hierarchy and the wealth hierarchy correlate closely.

Archaeological finds rarely give direct evidence of power, unless it is symbolised by a prince’s throne, as at Knossos (fig. 18.5), or by the princely sceptre imbued with a special meaning, such as we imagine for the Mallia find (fig. 18.6). They often yield information about wealth, however; grave goods are especially informative, and much of our information comes from this source. Ucko (1969, 266) has rightly indicated that wealth in grave goods does not necessarily correlate with wealth in life. Yet in the prehistoric Aegean the increasing richness, and the widening disparity between rich and poor, are certainly of note.

Wealth is not defined by the usefulness of goods owned so much as by their desirability. Gold, for instance, is less useful for most purely practical purposes than bronze or even lead, and a gold bar would be of small advantage in the world if no-one else coveted it. But gold is widely esteemed as precious, partly no doubt for its attractive appearance, partly for its rarity, and chiefly in accordance with a convenient social convention. The value of goods, and hence wealth, is indeed largely a matter of convention whereby a society covets one commodity rather than another. The feather decorations of the Aztecs, for instance, were prized by them more highly than gold yet were considered of little worth by the Conquistadores. Wealth, the ownership of desirable transferable goods, is as much a social phenomenon as an economic one.

In early neolithic times the scope for wealth was limited. Probably there was little that was enviable in owning more corn than one could eat, if others had enough, or more land than one could till. Livestock, of course, was a very real form of wealth, but the range of desirable artefacts was limited: stone axes, perhaps, and rare materials like obsidian. Spondylus and other shells may have been valued in communities lying at some distance from the sea. But in the Greek neolithic there is little evidence for any special value set upon particular kinds of stone axe, for example, such as we imagine for the jade axes of Britain or the battle-axes of early bronze age Troy. Very few burials are known from the neolithic Aegean, and until the Kephala cemetery the grave goods were so scanty, if there were any, that they can scarcely have been envied by the living.

The absence of grave goods is, in the first instance, a burial custom and need not lead us to doubt that stone bowls, for instance, or well-made figurines, or attractive beads and decorations of stone or shell, were indeed prized by their owners. But the finds are few, and do not indicate any special concentration in the hands of individuals.

In the third millennium the situation changes. As we shall see below, the whole new range of artefacts then available offered, perhaps for the first time, the possibility that one man could be conspicuously more wealthy than another. And the burials, especially in the Cycladic cemeteries, indicate that considerable disparity was emerging in the goods owned by individuals.

Already at Kephala in final neolithic times the position has changed: for the first time a complete marble vessel is included in a grave. And the grave goods do now show some variation between individuals.

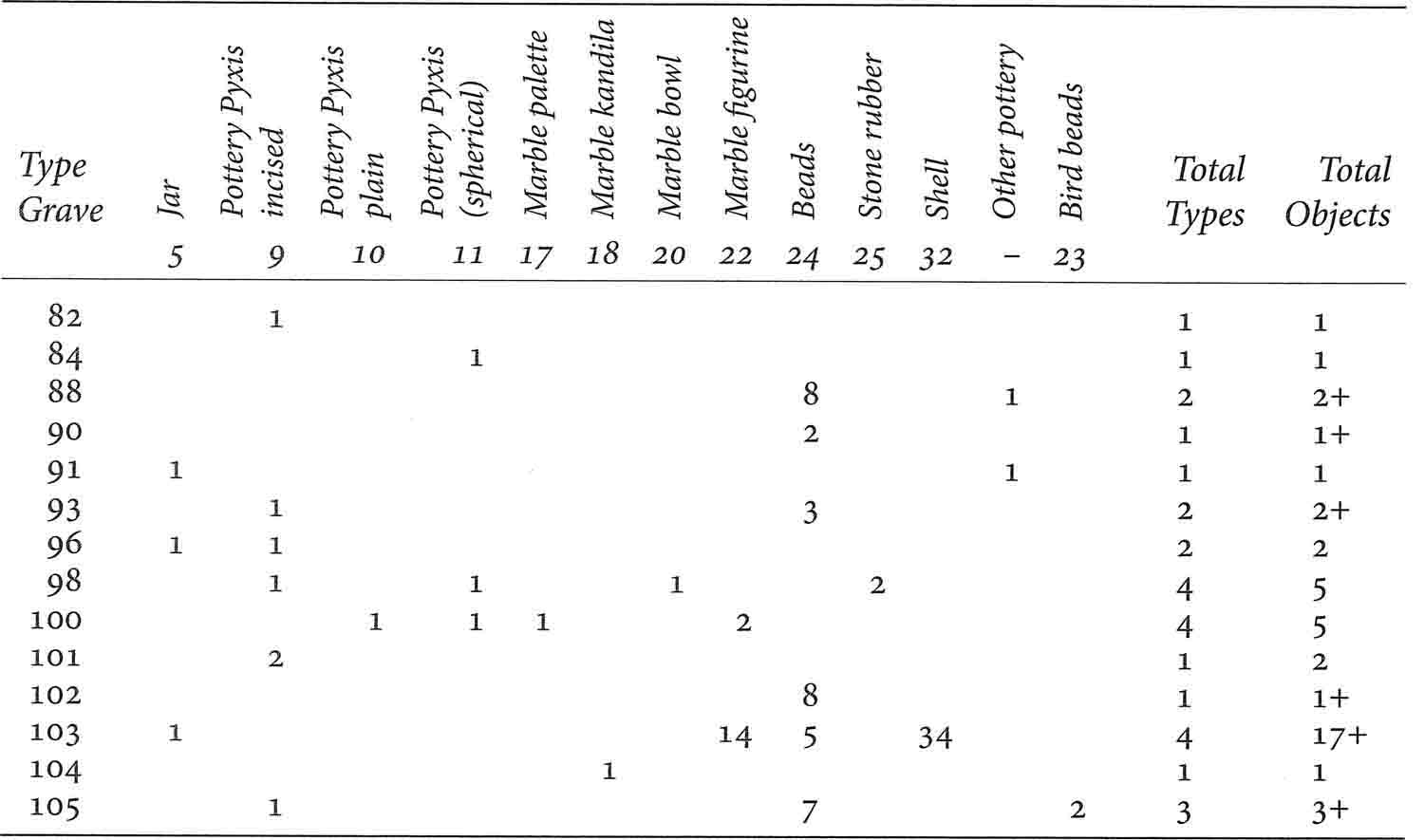

TABLE 18.1 Disparities in the wealth of grave goods in the Pyrgos cemetery of the Grotta-Pelos culture. (Note: several beads or shells are counted, in the final column, as a single object supplemented by a +.)

With the Grotta-Pelos culture in the Cyclades the disparities in the grave goods becomes very marked, although the actual range of types is limited. (The tendency of the Cycladic grave-good forms to fall into distinct types, and their range and variety, was discussed in chapter 9.) There are relatively few forms in which disparities can be expressed, but the variation which does occur is shown in Table 18.1. It sets out the grave goods which Tsountas (1898) found in fourteen of the richest tombs at the cemetery of Pyrgos in Paros. In all he excavated 58 cist graves in this cemetery, all rectangular in shape and made of schist or marble slabs, each originally containing a single burial. He reported the contents of the fourteen graves listed here, and it can safely be assumed that most of the remaining forty-four graves either had no grave goods, or only a single object.

We see then that the majority of graves have no goods, or a single vessel. With these may be contrasted Grave 103, which contained:

| 1 | Incised pottery jar (cf. Tsountas 1898, pl. 9, 1 and 4) |

| 14 | Schematic marble figurines (ibid., pl. 11: 4, 6, 7, 10 and 13) |

| 5 | Beads |

| 34 | Shells. |

This grave thus contained four distinct types, and more than seventeen objects. The other rich grave, Grave 100, contained:

| 1 | Cylindrical pottery pyxis (ibid., pl. 9, 14) |

| 1 | Spherical pottery pyxis with incised decoration (cf. ibid., pl. 9, 34) |

| 1 | Stone, possibly a headrest |

| 2 | Marble figurines (ibid., pl. 11, 14 and 17). |

This grave thus contained five objects of four different types. A similar impression is gained from the Panaghia cemetery, where Tsountas reported in detail ten graves of the twenty-three he excavated. Eight of these graves contained two different types of object, for instance a pottery vessel and a few blades of obsidian, and fourteen contained either a single type of object, or no grave goods at all. Only one grave (Grave 56) had a notably richer inventory:

| 7 | Pieces of obsidian (including three cores) (Tsountas 1898, pl. 8, 10 and 15) |

| 2 | Marble palettes (ibid., pl. 10, 11 and 15) |

| 1 | Stone, possibly a headrest (ibid., fig. 6) |

| 1 | Marble bowl |

| 1 | Bowl of other stone (ibid., pl. 10) |

| 4 | Beads of stone (ibid., pl. 8, 57–59) |

| 1 | Stone rubber |

| 1 | Shell |

| 4 | Pieces of copper wire. |

This grave thus contained more than ten objects of seven different types. Clearly then some of the graves contained rather richer goods than the average: others were entirely without goods. And while it does not follow that the goods buried with a man after death hold a very close relationship to those which he possessed in life, some correlation seems plausible in the present case. A similar impression is gained by the graves in Naxos excavated by Stephanos (Papathanasopoulos 1961–62) although unfortunately of more than five hundred opened, we have details of only fourteen.

The graves already discussed, of the Grotta-Pelos culture, are to be set in the Early Bronze 1 period. The Kampos group, discussed in chapter 10 and Appendix 2, falls at the end of this period. Apart from the Kampos (Aghios Nikolaos) finds, it is represented by the Louros grave, which contained Grotta-Pelos ceramic forms as well as a ‘frying pan’ of Kampos type, and some metal objects. It is, by the standards of the time, exceptionally rich and contained:

| 2 | Undecorated pottery spherical pyxides (Papathanasopoulos 1961–2, pl. 67 a, d) |

| 5 | Miniature pottery jars decorated with spiral incisions (ibid., pl. 66, lower) |

| 1 | ‘Frying pan’ of Kampos type (ibid., pl. 66, upper) |

| 1 | Marble bowl (ibid., pl. 67, b) |

| 1 | Marble saucer (ibid., pl. 69) |

| 15 | Pieces of obsidian (including one core) (ibid., pl. 68) |

| 1 | Stone bead (ibid., pl. 67, 2) |

| 4 | Shell beads (ibid., pl. 67, e) |

| 7 | Marble figurines of Louros type (ibid., pl. 70) |

| 200 | Silver beads forming a necklace (ibid., pl. 67, c) |

| 4 | Copper quadrangular awls (ibid., pl. 68, lower). |

This remarkable grave thus contained more than twenty-five objects of no fewer than eleven different types, and is certainly the richest known of those dated to the Early Bronze 1 period.

During the succeeding Keros-Syros culture, the presence of metal objects automatically increases the variety range. And the disparities between rich graves and poor graves are consequently magnified.

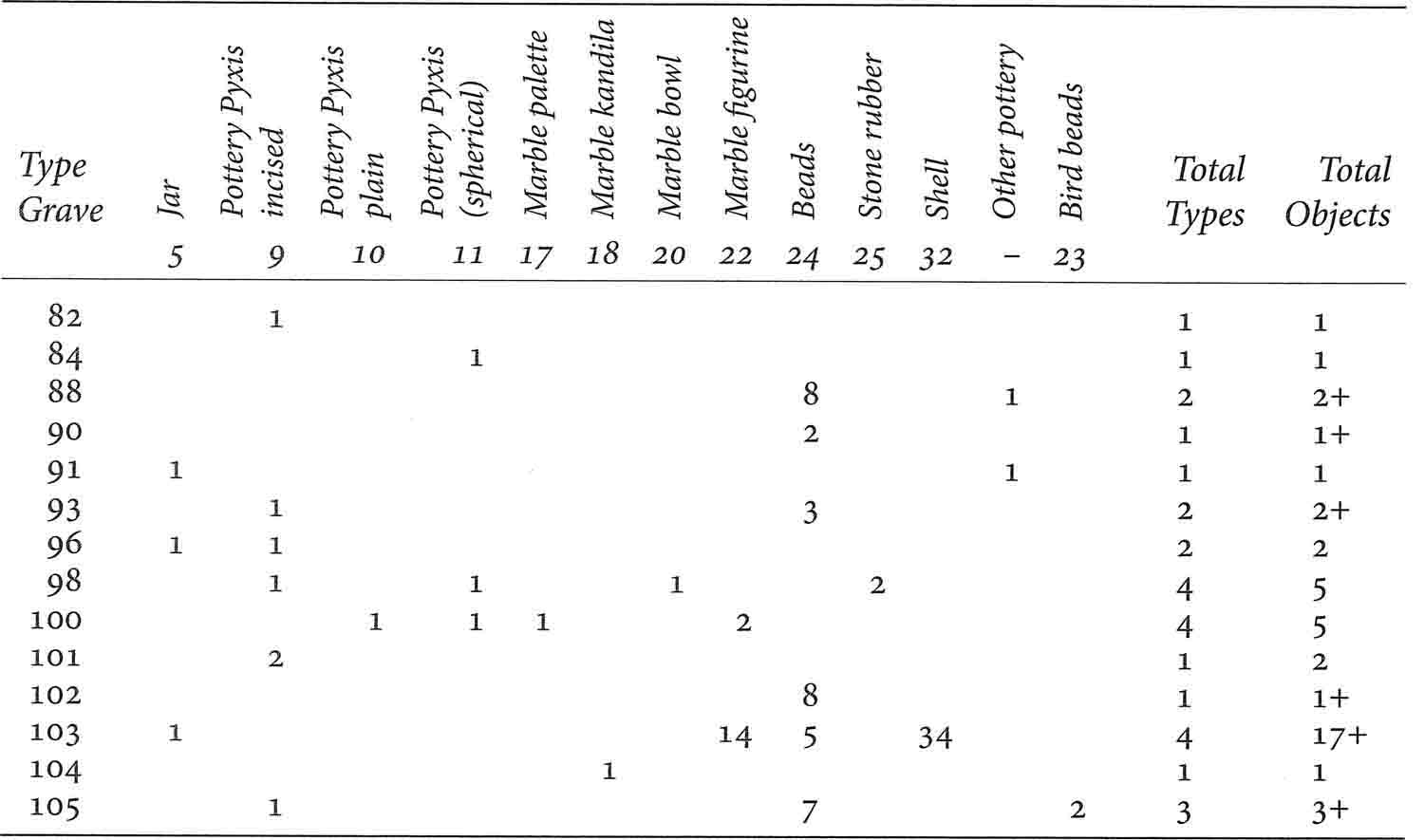

Tsountas himself excavated four hundred and ninety graves at the great cemetery of Chalandriani in Syros, giving details of thirty-two of the richest. Their contents are tabulated in Appendix 2. He also listed the totals of certain classes of object found, and we may compare their occurrence in the total cemetery with their occurrence in the thirty-two specified rich graves.

If the assumption be made that Tsountas chose the samples simply by selecting those graves with the greatest number of objects, irrespective of the nature of the object (although in fact he seems deliberately to have favoured graves with painted pottery or marble figurines), then the following computation can be made. The frequencies of selected types among the richer graves are examined, and contrasted with the figures given by Tsountas for the cemetery as a whole.

These results are very interesting: they show that the rich graves are not simply distinguished by a large number of types or by a considerable quantity of objects. These rich graves have an inordinate preponderance of certain types. If the grave goods were randomly distributed throughout the graves of the cemetery we would expect a sample of thirty-two graves to contain approximately 7 per cent of the total objects of each type which are found in the cemetery. We see from Table 18.2 that for many classes of object they have a vastly greater proportion, with no less than two-thirds of all the occurrences of copper tweezers found in the entire cemetery. Even more remarkably they actually have less than a normal or average share of two specific types. Little pottery cups and small pottery bowls are actually less common amongst these rich graves than in the rest of the cemetery.

TABLE 18.2 Analysis of contents of graves of the Chalandriani cemetery with particular reference to the 32 rich graves described by Tsountas. The selected types are listed in rank order of their concentration in these rich graves. (Tc indicates pottery; F.P. indicates ‘frying pan’)

In other words, certain specific types tend to be concentrated predominantly in the hands of the rich. In terms of modern society this is quite unsurprising, but in prehistoric society it implies the emergence of an artefact assemblage associated with a select group of people. This is a property distinction not only of degree but of kind. And the particularly interesting counterpart is that the simple pottery cup with concave sides and the simple saucer or rounded bowl (types 45 and 54) were actually avoided by the rich. We see here, perhaps, the emergence of snobbery! There could be no clearer indication that the concept of wealth was consciously held at this time.

Setting aside the marble figurines and bird-headed pins, which were present only in small quantities, we may divide the types into four groups:

(i) Types more than ten times more frequent in richer graves than in the others. These include copper spatulae, copper tweezers and ‘frying pans’.

(ii) Types five to ten times more frequent in richer graves: bone tubes, copper pins with decorated heads, painted pottery.

(iii) Types two or three times more frequent in richer graves: obsidian, copper needles, footed pottery vessel

(iv) Types less common in richer graves than in poorer ones: pottery cup, pottery bowl.

As far as can be detected there is otherwise little strong correlation between the types and I have been able to detect no systematic association among the finds which could indicate a sexual distinction: we cannot assume that men did not use needles or take special care over their appearance. No weapons are found in the graves, nor indeed copper axes or chisels, although the settlement finds show that the inhabitants possessed them.

The almost aristocratic nature of some of the graves, contrasted with others, may be indicated by four examples, first the poorest pair and then the richest pair of the thirty-two graves which Tsountas records in detail: the vast majority of the graves, of course, were poorer than any of these.

‘Grave 157. About ellipsoidal, diameter 1.0 m × 0.3 m. The body lying on its right side. By the skull a painted footed cup, and a pottery saucer of the usual kind.’

‘Grave 415. About rectangular, width 0.6 m. On the left side of the grave a spherical pyxis and a schematic figurine of marble.’

‘Grave 356. The body on its left side. By the head a footed vessel with stamped and incised decoration, a marble bowl and an obsidian blade. Behind the head a frying pan, a stone palette and a grinder. By the feet a marble bowl with traces of red colouring, a seashell, copper tweezers, a carved bone tube containing traces of blue colouring, a straight bone tube with a copper spatula beside it, a bone pin with bird head, two bone fragments perhaps from another pin, and two lumps of red colouring matter.’

‘Grave 468. Quadrilateral, 1.4 m × 0.8 m. In the right upper comer a copper awl, a stone palette, a pebble rubber and a cup with a leaf impression upon the base. In the wall on the right side was a cavity measuring about 0.4 m × 0.2 m, in which was hidden a pottery-footed vessel with stamped and incised decoration, two seashells, three copper spatulae, a copper pin with double spiral head, a copper pin with complex knot head, three copper needles, two awls, six stone beads, a bone ring and fragments of another, pieces of a bone tube, ten worn shells and a schematic marble figurine’.

None of the graves of the Keros-Syros culture in Naxos had as many goods as this. But the rich Grave 10 of the Spedos cemetery already mentioned in chapter 15, was extremely rich. Exceptionally too it contained two types of lamp, which are unique; normally the finds in graves—even in Syros—correspond closely to a defined repertoire of types. The finds were as follows: (fig. 15.7; Papathanasopoulos 1961–62, pls. A, B, and 46–50).

| 2 | Marble folded-arm figurines |

| 2 | Marble bowls |

| 1 | Spouted marble bowl |

| 1 | Triple lamp of marble |

| 1 | Painted pottery triple lamp |

| 1 | Painted pottery ‘sauceboat’ |

| 2 | Painted pottery jugs |

| 1 | Footed and spouted pottery bowl |

| 2 | Large footed jars with incised decoration. |

This grave documents eloquently the growing wealth of some members of the community.

Turning now to the Amorgos group of the Keros-Syros culture, which extends in time into the Early Bronze 3 period, the presence of weapons in the graves is noteworthy. They do not occur in the Syros graves, and rather rarely in Naxos. While the Syros goods indicated personal wealth of an almost aristocratic kind, some of the Amorgos finds are verging upon the princely in their nature. Three grave groups will be described.

Dokathismata Grave 14 (Tsountas 1898, 154)

| 2 | Marble folded-arm figurines (pl. 30, 1 and 2) |

| 1 | Copper slotted spearhead |

| 1 | Midrib dagger with silver rivets |

| 1 | Pottery jar |

| 1 | Fragmentary clay bowl |

| 2 | Marble bowls |

| 1 | Fragment of a silver bowl. |

Kapros Grave D (Renfrew 1967a, pls. 4 and 10)

| 1 | Silver bowl (pl. 19, 5) |

| 1 | Needle of copper |

| 2 | Greenstone handles |

| 1 | Greenstone cylinder seal (pl. 23, 2) |

| 22 | Beads, including 3 of silver |

| 1 | Ivory fragment, with drilled circles |

| 2 | Shell figurines |

| Marble figurines |

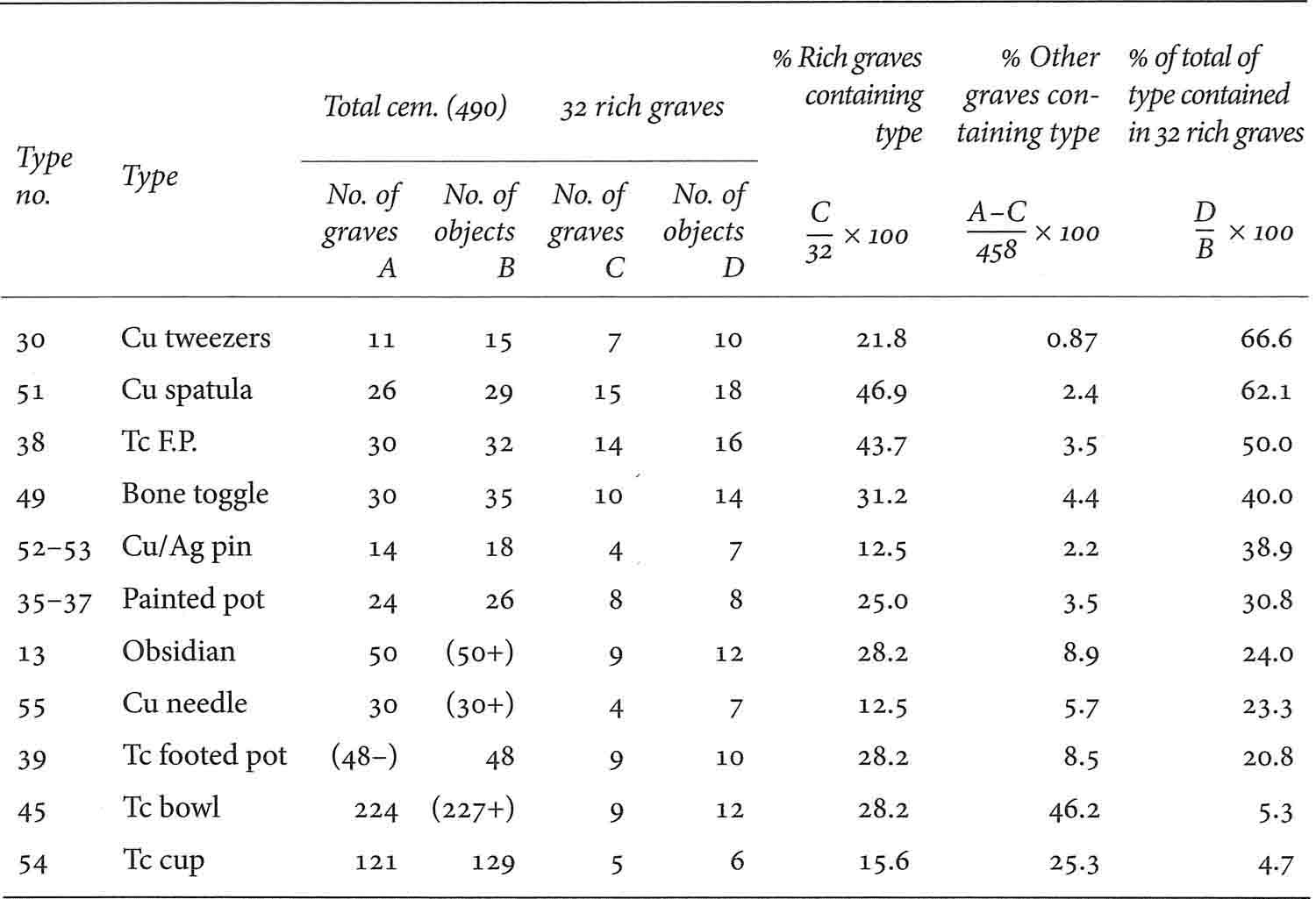

Dokathismata Grave 14A (Tsountas 1898, 154–55)

| 1 | Silver diadem (fig. 18.1, 2) |

| 1 | Silver pin with animal head (fig. 18.1, 4) |

| 1 | Silver bowl |

| 2 | Silver bracelets (fig. 18.1, 3) |

| 1 | Marble bowl |

| 1 | Pebble grinder with traces of red colouring |

| 1 | Lump of red colouring matter |

| 1 | Pottery jar with leaf impression on the base |

| 1 | Marble figurine (type not specified). |

The finds in these graves, especially the last, are much more splendid in themselves than anything in the Syros graves. We see now vessels of precious metal, impressive weapons (with silver rivets) and, above all, personal adornments. The diadem and silver bracelets of Grave 14A at Dokathismata may well be emblems signifying a high status—perhaps that of a chief of some kind. They certainly would have conferred prestige in their own right. The same holds true, of course, for the diadem from the settlement at Chalandriani (fig. 18.1; Tsountas 1899, pl. 10, 1).

FIG. 18.1 Social status in the third millennium BC. Silver diadems and ornaments from the Cyclades. 1, from Chalandriani in Syros; 2 to 4 from grave 14A at Dokathismata in Amorgos.

These finds give a clear picture of the emergence of a social stratification during the early bronze age—at the beginning marked by a slight variation in the quality and quantity of grave goods; by the end indicated not only by greater quantities of finds, some concentrated in the wealthy graves, but also by the avoidance of ‘common’ types and the rare inclusion of princely (or at least ‘chiefly’) objects.

One important consequence of these burials should not be overlooked: the considerable stimulus to the economy arising from the regular burial (and hence elimination) of so many desirable goods. This resulted in a sustained demand for such objects, which might otherwise have been satisfied in part by the inheritance of heirlooms, and favoured a higher level of production than otherwise would have been necessary.

Various other rich grave finds of this period have been made in the Aegean. The Cretan ones, although they testify to comparable wealth, are not susceptible to the same kind of analysis, since the burials were in general collective, and individual burial associations cannot be ascertained. Yet we may note the riches of Tomb II at Mochlos, where eighty-five gold ornaments were found accompanying only three seals and three dagger blades. The presence of secondary burials and the possibility of disturbance complicate the situation, and yet we can say that one or more of the individuals buried In Tomb II at Mochlos was very much richer in grave goods than the average occupant of the Mesara tholoi could possibly have been.

Again, in the earlier phases, the finds of Pyrgos and Kanli Kastelli, which are chiefly ceramic, document an emerging variety. Those of Platanos (Xanthoudides 1924), Lebena (Alexiou 1958), and especially Mochlos, with their rich and beautiful goldwork, hint at the same kind of stratification as is Indicated by the silver of the Amorgos graves. There were several golden diadems amongst the goldwork of Tomb II at Mochlos (fig. 6.8; Seager 1912, 22), and the finds are assignable to the Early Minoan II period. Tomb XIX was almost as rich. In Crete, the beautiful and finely worked stone bowls were clearly an important part of the rich man’s wealth.

The finds of the period in mainland Greece have not, in general, been so rich. There were some attractive finds at Zygouries, however, and the important cemetery at Steno on the Ionian island of Levkas yielded a number of rich graves whose associations are recorded. Two will be listed here, not only to document the considerable quality or range of goods which accompanied certain burials, but to stress the inherently costly character of some of them.

Grave R1 (fig. 18.2; Dörpfeld 1927, pls. 60, 1 and 5; 61, b, 7; 62, 10; 63, c, 6; 64, 1–3; 67, a, 1)

| 1 | Silver bracelet |

| 1 | Necklace of gold beads |

| 1 | Copper spatula |

| 1 | Spindle whorl |

| 18 | Obsidian blades |

| 1 | Pottery ‘sauceboat’ |

| 1 | Pottery bowl |

| 1 | Pottery footed cup |

| 2 | Pottery vessels |

| 1 | Large pithos. |

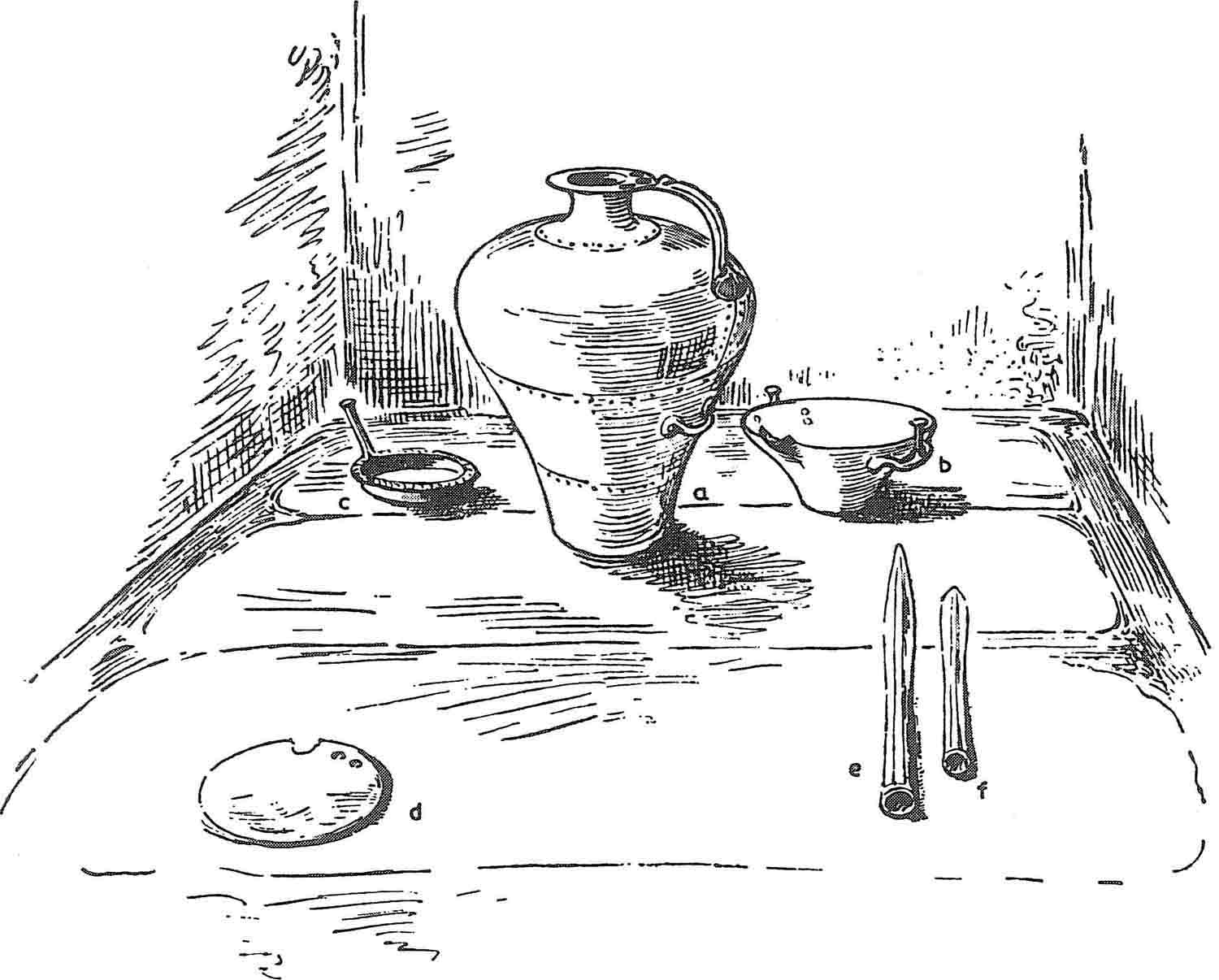

FIG. 18.2 Grave R1 of the third millennium cemetery at Steno in the Plain of Nidri on Levkas. Note the presence of gold, silver, copper (or bronze) and obsidian.

FIG. 18.3 Wealthy men and women. (Above) finds from what was probably the grave of a man (R 17a) at Steno in Levkas. Note the gold sheath for the dagger hilt, and the use for the burial of a spouted pithos of the kind used to store wine. (Below) finds from what may have been the grave of a woman, in the same cemetery. Note the gold and silver adornments, the bone tubes (possibly to contain cosmetics), and the terracotta spindle whorl.

Grave R17a (fig. 18.3; ibid., pl. 61, a, 4 and b, 3 and 5; 63, a, 3–4 and 6–8; 67, b, 5)

| 2 | Copper midrib daggers |

| 2 | Gold sheet coverings, for dagger hilts |

| 1 | Flint blade |

| 2 | Copper nails |

| 1 | Copper knife |

| 1 | Large pithos. |

These may very well be regarded as chieftains’ graves, the first (R 1) for a woman, the second (R 17a) for a man. The associations for the cemetery are predominantly of the Korakou culture, and the finds indicate that the same process of emerging stratification was taking place in western Greece as in the Aegean proper.

Finally, the richest early bronze age finds of all are, of course, the treasures of the eastern Aegean. The fine treasure of Vano 643 at Poliochni contained a magnificently rich series of personal adornments, more splendid than any found in the cemeteries of the time (Brea 1957, 206 f.). The chief prize was a golden dress pin decorated with two birds in antithetic arrangement (pl. 18, 5), with several elaborate pendant earrings, bracelet tores of gold, golden buttons and four fine bead necklaces. This was the apparel of a personage of note, and indeed if the wealth is indicative of social stratification, of high rank.

These finds are surpassed only by the treasures of the Second City of Troy, discovered by Schliemann. Among the dozen or so ‘treasures’—associated groups of rich material—two are of special note in addition to Treasure K, which was mentioned in chapter 16 and, although of metallurgical interest, is without precious finds.

Troy Treasure A was of astounding wealth (fig. 8.5; Schmidt 1902, 225)

| 19 | Plate vessels comprising 3 of copper, 12 of silver, 1 of electrum and 3 of gold |

| 3 | Golden diadems (2 of them with elaborate pendants) |

| 4 | Elaborate golden earring pendants |

| 51 | Small golden earrings |

| 4 | Golden bracelets or earrings |

| 26 | Beads and oddments of gold |

| 6 | Silver bars (fig. 19.1) |

| 19 | Daggers and spearheads of copper and bronze (some fragmentary) |

| 17 | Flat axes of copper or bronze |

| 4 | Chisels of copper or bronze |

| 1 | Knife of copper or bronze. |

Very notable here is the absence of objects other than of metal, and the presence of bronze tools and weapons together with the plate and jewellery. The fragmentary nature of some of the bronze objects reveals that this may not have been a personal or even collective deposit of valuables but rather plunder (or a hasty assemblage of valuables) gathered together during the destruction of the city. It need not necessarily represent the possessions of a single person, but the magnificence of some of the objects make an even more impressive impact than the Poliochni treasure.

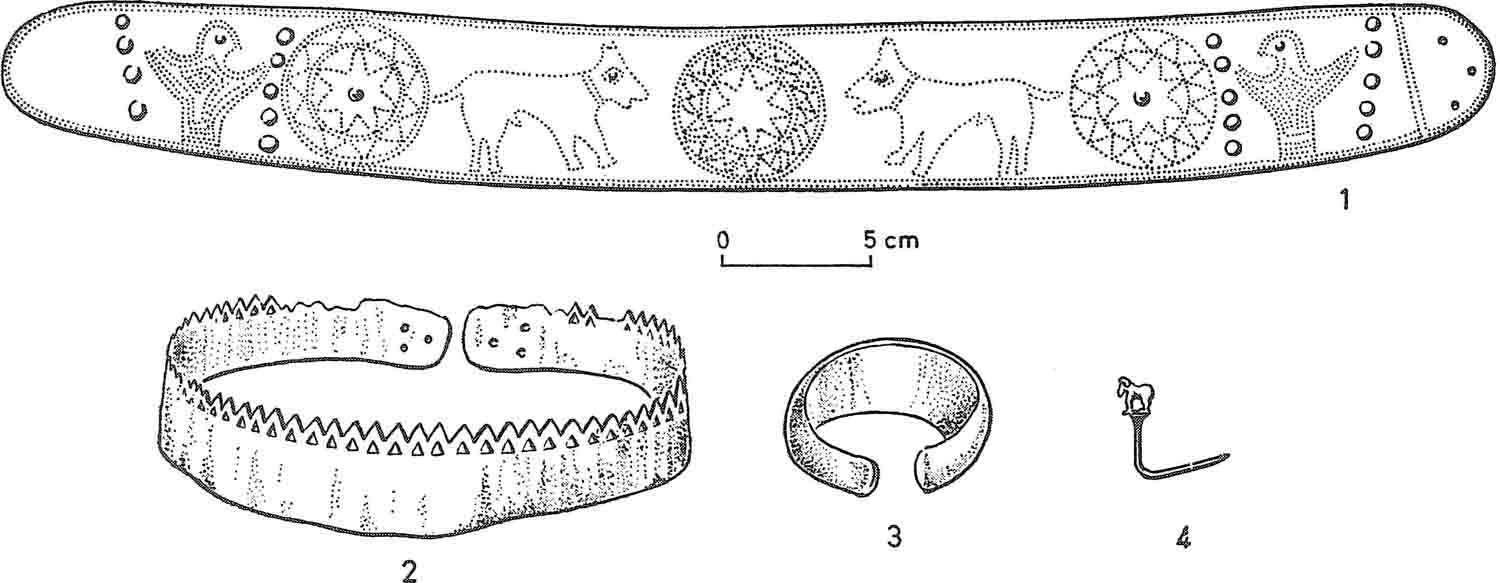

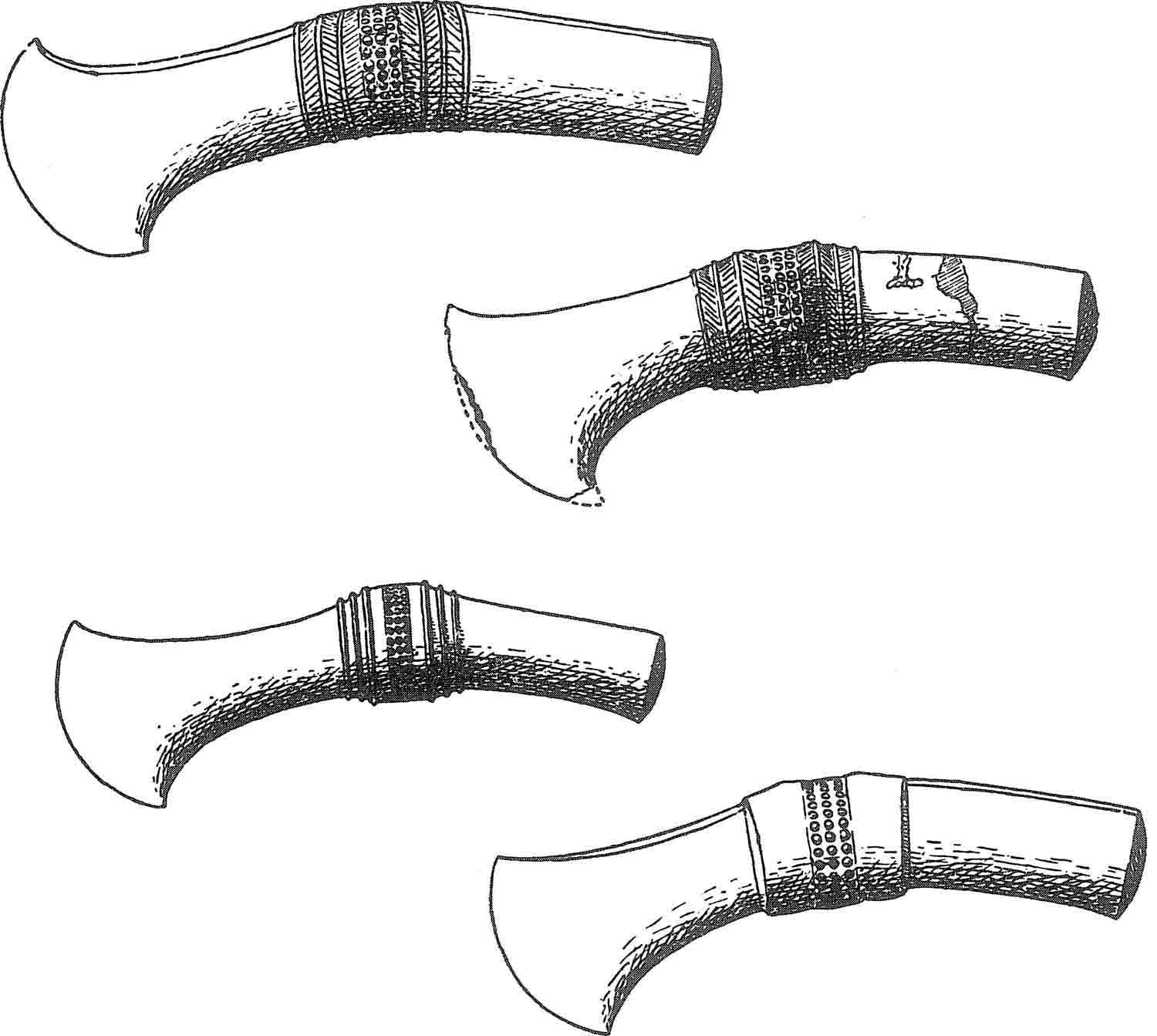

Treasure L from Troy is strikingly different in character. Its great glory is four magnificent battle axes of finely worked and attractively coloured stone (fig. 18.4). There were also six knobs of rock crystal, possibly dagger pommels, and forty-five plano-convex pieces of rock crystal which may have decorated a metal girdle, four stone beads, a pommel (apparently of iron), and numerous small gold, silver and faience beads. (The presence of amber beads in this hoard is uncertain.)

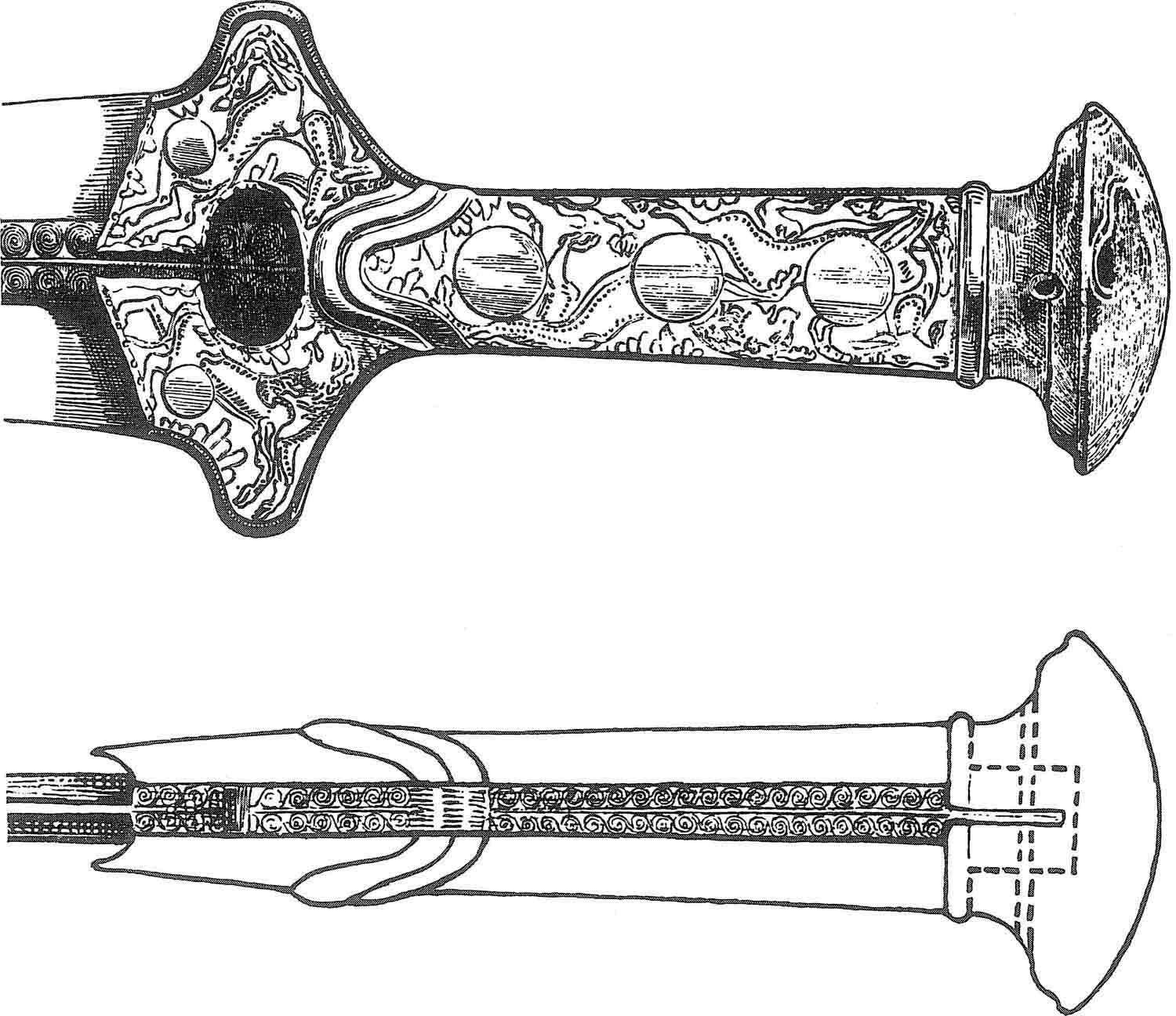

FIG. 18.4 Weapons of display, from Treasure L at Troy II. The battle-axes are of green or blue stone, of length c. 30 cm (after Schmidt).

The shaft-hole axes here must surely be taken as the emblems of a chieftain or prince: they are not objects simply for use. The various objects of crystal clearly ornamented weapons and apparel of a similarly symbolical nature.

Treasures M and O are also relevant, since, like A and L, each contains objects which are absent from the others. Treasure M contained quantities of carbonised cloth, and a faience object, possibly a handle. Treasure O (Schmidt 1902, 245) contained the two gold pins so conspicuously lacking from Treasure A. The remaining treasures (apart from K) simply duplicated the finds of Treasure A.

The function of the various buildings of Troy Ilg has been discussed by Mellaart (1959a). Whether or not he is correct in thinking that a large proportion of the buildings were in the use of the central administration, it seems likely that several of the treasures (especially A, L, M and O) formed part of the wealth of the chief man of Troy. Taken together they yield a homogeneous impression of massive personal (or collective) wealth: plate, jewellery (diadems, earrings, necklaces, pins, bracelets, beads and crystal adornments), textiles, metal weapons, crystal and faience pommels, ceremonial shaft-hole axes, silver bars, and various metal tools.

There are only two or three diadems, two or three pairs of pendant earrings, and two or three dress pins, so that very few persons (whether male or female) could be decked out in all this finery. And the axes and accessories would be appropriate for a single prince, or at most four chiefs. Social stratification and hierarchy are clearly implied. The battle-axes, like the several diadems of Syros and Amorgos, and the golden sword-hilts of Levkas, seem to be emblems of chieftainship rather than simply rich goods.

During the early bronze age, as we have seen, wealth, hierarchy and authority are indicated by the artefacts found. They are yet more clearly indicated in Crete in the middle and late bronze age, and in mainland Greece from the end of the middle bronze period. (Our material from the earlier Middle Helladic period is unfortunately much more limited.)

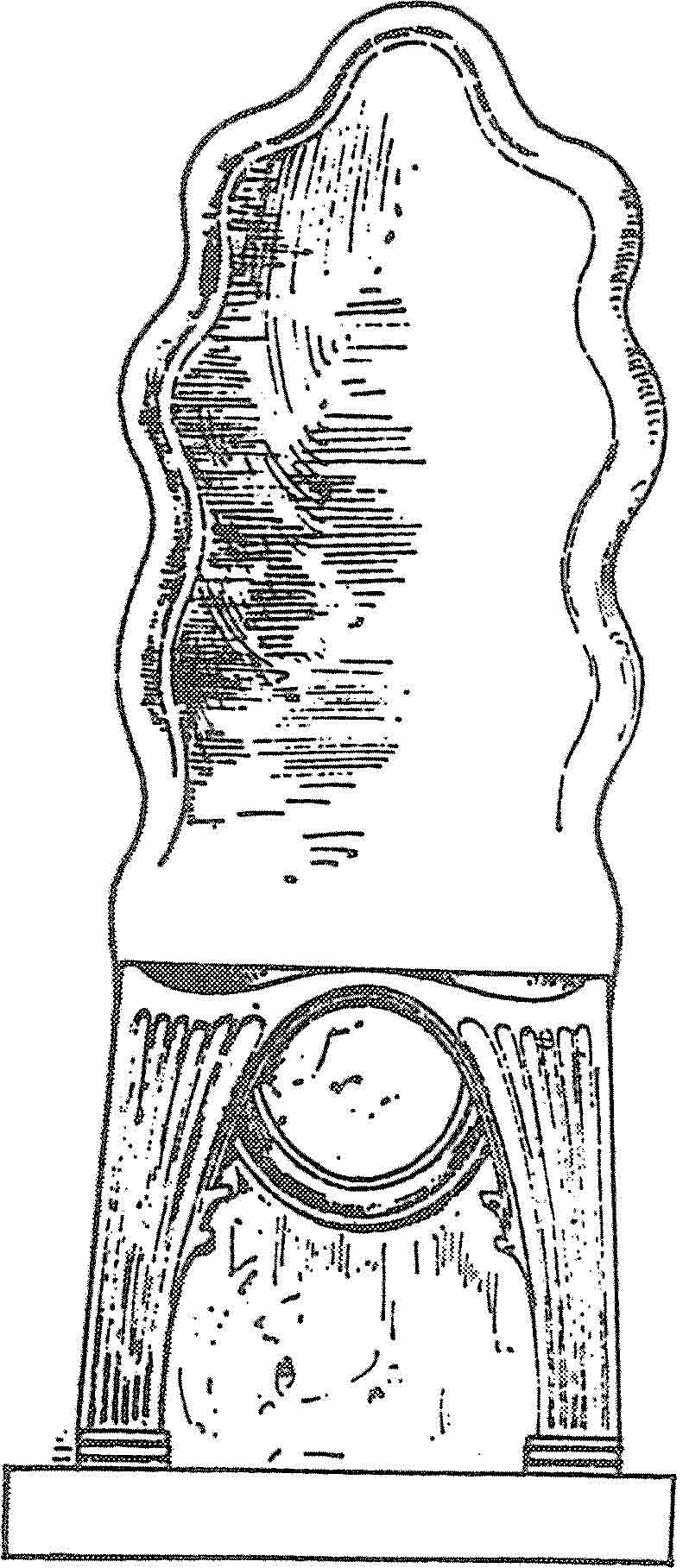

FIG. 18.5 The symbol of princely authority: the Late Minoan throne in the Palace of Minos at Knossos (after Evans). Ht 1.40 m.

The palaces of Crete might themselves be taken as indicating the existence of a prince. This is underlined by the throne of stone in the last palace at Knossos (fig. 18.5), and by the treasuries of the palaces, especially at Zakro. That the palaces imply just such a hierarchical structure in the first palace period is documented for us by the magnificent associated groups from the First Palace at Mallia.

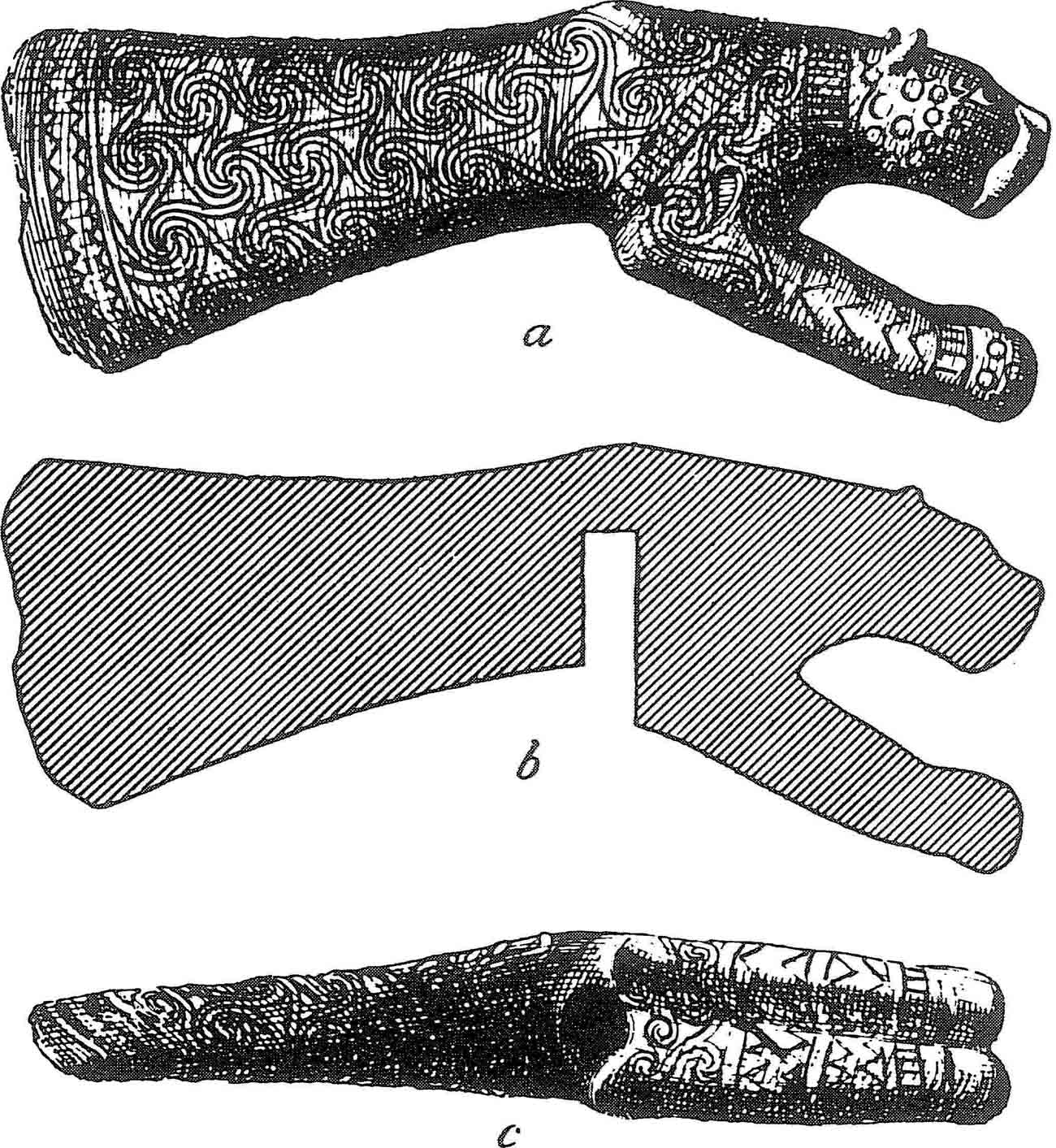

FIG. 18.6 Ceremonial axe-head from the Middle Minoan palace at Mallia. This symbolic ‘axe’ (made of schist) was found together with the ceremonial longsword, fig. 16.6 (after Evans). Length 15 cm.

Mallia Treasure I was found together in Room RVI.II, just west of the central court at Mallia (Chapoutier and Charbonneaux 1928, 25, fig. 3; Charbonneaux 1925). It consisted of a sword, a dagger, a bronze bracelet, and a shaft-hole sceptre, with a pottery vessel (fig. 18.6). Charbonneaux originally dated the find ‘not later than Late Minoan I’ but the context clearly sets it in the First Palace period (Hutchinson 1962, 186; Pendlebury 1939, 118): Pendlebury dated it to Middle Minoan I, and Evans set the sword at the transition from Early Minoan III to Middle Minoan I.

The great sword (fig. 16.6) is 80 cm long in the blade. It has a hilt of fine limestone, covered in sheet gold, and a beautiful pommel of crystal. The sceptre of brown schist (fig. 18.6) is in the form of a panther straining on the leash, and covered with an elaborate design of interlocking spirals derived from the stone vases of the early bronze age. Of course it merits comparison with the display axes of Troy II, already discussed, and the crystal pommel finds counterparts in the same treasure, Treasure N, as contained the axes at Troy. But the sword is unique, the earliest known from the Aegean. As Pendlebury puts it, we may regard the group as ‘part of the regalia of the king of Mallia’ (1939, 118).

Mallia Treasure II consists of two swords of display found in 1936 north of Quartier III at the north-west corner of the palace (Chapoutier 1938). These swords, although dated to the Middle Minoan III by Hutchinson (1962, 188), seem to belong, with the ruins of the First Palace, to the Middle Minoan I or II period (Branigan 1968a, 64). Both swords had the round shoulders and short tang of Karo’s type A (cf. Sandars 1961). The first was of length 81 cm, while the second, of length 72 cm, was fitted with a magnificent pommel. The lower part of this pommel, of bone, was decorated with a beautiful gold roundel portraying an acrobat, his body forming a circle by bending the legs backwards until they touch the top of the head. It is one of the masterpieces of Minoan art.

FIG. 18.7 Warrior aristocracy: stone stele from Shaft Grave V at Mycenae (after Evans). Ht 1.33 m.

These two finds eloquently indicate the princely status of the ruler of Mallia, who was equipped with these splendid weapons of display. Clearly the sceptre, like the axes of Troy, was not intended for use, but had a purely symbolic value.

The later prehistoric periods in Crete provide abundant further evidence of this kind: the tombs of Zapher Papoura, and the warrior graves near Knossos serve to indicate the existence of an aristocracy, while the Royal Tomb of Isopata hints at the wealth of the prince.

A fascinating example of pecuniary emulation in the late bronze age is afforded by the practice of burying in the tombs pottery vessels coated with tin foil so as to have the appearance of silver plate (Immerwahr 1966). They are not usually found in the princely tholos tombs, where real metal vessels could be afforded, nor in the poorer of the chamber tombs, but generally in the richer and better equipped chamber tombs (ibid., 386). These were the grave goods of aristocrats who existed, none the less, on a markedly lower social level than the princes.

The evidence for social stratification in the Mycenaean world is comparable with that from Crete. The incredibly rich finds of the Shaft Graves document the rule of a very wealthy, princely dynasty from at least the end of the middle bronze age (fig. 18.7). The earlier grave circle, Circle B, is less wealthy than Circle A, so that the riches of the dynasty were increasing at the onset of the late bronze age. That they continued to do so is clearly indicated by the impressive tholos tombs of Mycenae. The rich finds at Vapheio, at Dendra, in Messenia, and at Kakovatos and at other sites, together with the tholos tombs themselves, testify to the rule of analogous dynasties elsewhere.

But all this is sufficiently established by the enormous contrast between the finds of Pelos, Kephala or Paterna around 3000 BC, at the beginning of the early bronze age, and the regalia of Mallia around the twentieth century BC, not long after the end of the early bronze age. The Cycladic graves supply the best detailed indication of the nature of the transition, where a disparity in personal wealth is shortly followed by clear indications of social stratification, and ultimately of chieftains.

The craft specialisation of the late bronze age palaces, so clearly indicated in the material record, was sustained by the system of redistribution centred upon them. The clear indications of the storage of large quantities of foodstuffs were described in chapter 15, and reference made to the system of agricultural production quotas and palace rations indicated by the tablets. Such a system was functioning already in the first palaces of Crete in the Middle Minoan period, as the indications at Mallia clearly show. Already there are palace stores and workrooms, and the hieroglyphic tablets seem to be the direct precursors of those of Linear A.

It is during the third millennium that the origins of this redistribution system must be sought. Indeed there is already evidence for granaries of large size, as we have already seen.

In a simple village economy, where each household functions largely as an independent economic system, consuming the bulk of what it produces, the scope for trade or redistribution is limited. This is clearly seen in many rural villages in Greece today, for many households do not produce a significant surplus which (in a modern folk economy) they could sell at market. In Crete in 1948, for example, the average annual cash income of the majority of the population, the poorer 60 per cent, has been estimated at twenty-six dollars (Allbaugh 1953, 491).

Probably it is only with the development of some systematic circulation or transfer of goods that problems emerge in establishing ownership, provenance and destination. It seems plausible, therefore, to associate the emergence of seals and sealings in the Aegean in the third millennium BC with the movement and apportioning of produce in this way. On their own they need not indicate any centralisation in the movement of produce, although this is not excluded. But they do hint at some kind of distribution or exchange system, however it may have been structured.

In Crete the art of seal engraving reached an early high point in the Early Minoan period. Seals of Early Minoan II date are documented from Lebena, Mochlos, Myrtos, and possibly Krasi and Sphoungaras (Kenna 1960, 15; Warren 1969c, 25; Warren 1970, 31). The Mesara tombs contain a great abundance of seals, some of which must also date from this period; Kenna’s survey gives a clear indication of their range and variety (fig. 6.7). Unfortunately the actual use of the seals is not well documented, for clay sealings or seal impressions are not found in the tombs, from which the bulk of our evidence for Early Minoan Crete comes. Myrtos (Phournou Koriphi) again has yielded a sealing with impressions of two different seals.

It seems likely that most men, or at least most family heads, possessed their own seal. Although the Mesara tombs had all been robbed during their period of use as well as subsequently, and many seals have perished with the years, an order-of-magnitude impression may be gained of the correlation between seals and daggers.

The number of burials was originally, no doubt, very much larger than these figures might suggest.

We must imagine each man or householder marking his own produce or his own goods with his personal seal, making the sealings already documented from the Early Minoan period and so common later. There would be no point in this if the goods were to remain in his personal store, at home. The sealings therefore seem to indicate not so much the emergence of a concept of ownership but of a distinction between ownership and immediate possession. If the goods were exchanged on a purely face-to-face basis, the ownership would be transferred immediately with possession, as is normal in barter transactions. Here, however, the suggestion is that the goods remained in some sense ‘his’, as goods belonging to or consigned from the owner of the seal, even after they left his possession.

In the centralised palace administration, it may be supposed, many of the consignments of goods entering the palace from the outlying dependencies would be sealed and stamped to show their place of origin. The whole elaborate system of accounting seen in the tablets must have grown up in order to cope with the problem of systematically disposing of these consignments. Many deposits of sealings have come from the palaces: the most important from Middle Minoan Knossos are the Hieroglyph Deposit and those from the Temple Repositories (Kenna 1960, 37 f.). And in the Archives Deposit, of Late Minoan date, sealings were found associated with Linear B tablets. That we possess only a tiny fraction of the seals originally In use (and a totally insignificant proportion of the sealings) is indicated by the remarkable fact that none of the sealings yet found appears to be the impression of any seal now extant (ibid., 58).

TABLE 18.3 Comparison of the number of daggers and sealstones found in some of the Mesara tombs, suggesting that each male occupant may originally have been buried with a single dagger and sealstone.

| Mesara Tomb | Daggers | Seals |

| Koumasa B | 25 | 20 |

| Koumasa A, E, γ | 11 | 13 |

| Kalathiana | 7 | 6 |

| Platanos | 70 | 45 |

Further clues about the use of the seals are given by the countermarks on some of the sealings, incised in Linear A or B script (Gill 1966) and by the important observation of Marinates, discussed by Betts (1967), that several sealings from Sklavokampos near Knossos were made from the same seal or signet as sealings at Aghia Triadha and Zakro. Clearly too the seals will have had many functions, not all of them economic: some of them are thought to have been of talismanic significance.

The existence of seals in the Early Minoan period, although apparently indicating a systematic circulation of goods, perhaps on a basis of credits or of obligations, does not necessarily imply a central agency of the kind provided by the palaces in Middle Minoan times. The system could have worked on a more flexible, inter-personal basis. Indeed Kenna has called attention to a decline in the style and execution of seals at the beginning of the Middle Minoan period, a decline so striking that ‘lessened prosperity would not have had so profound an effect.... This state of affairs was reversed in Middle Minoan II, but in the interim there seems to have been a change in the character and use of the seal, perhaps contemporary with greater changes in the social and political structure of Crete’ (1960, 32). It is tempting to correlate this change with the emergence of a centralised system, organised at the palaces which were founded at this time. The greater simplicity of a palace-based redistribution, where most consignments were either to or from the palace, may have contrasted with the earlier, more complex situation where a much greater number of people, including local village chiefs, were recipients. Any explanation at present is conjectural, but the central point remains that seals and sealings must have been an important element in the economic life of the Early Minoan period, and that this practice of sealing subsequently became an integral part of the redistribution system of the palace economies.

Seal stones are much rarer elsewhere in the Aegean, during the third millennium, than in Crete. Several are known from Poliochni, including a cylindrical seal of ivory which may be an import (pl. 23, 3; Brea 1964, 587 and 653; 1957, fig. 25). Several terracotta seals of both button and cylinder form were found by Schliemann at Troy. A cylinder of blue stone was found in the principal building of the Second City at Troy, while Blegen found a sherd with a seal impression in the Second City levels (Schliemann 1880, 415–16; Blegen et al. 1950, 256), although the pottery was of imported fabric. A stamp seal was likewise found at Thermi (Lamb 1936a, 172).

The evidence for actual seals in the Cyclades and the mainland is similarly limited. A grave at Kapros in Amorgos yielded a cylinder seal (pl. 23, 2), while a small square button seal was found in the Kouphonisia (Dümmler 1886, pl. 1, 1). Pots at Chalandriani in Syros are decorated with seal Impressions (Bossert 1960, 12, fig. 11), quite apart from the series of stamped circles and spirals with which the ‘frying pans’ and other vessels were decorated.

Several seals are known from mainland Greece, from Zygouries, Raphina, Asine and Aghios Kosmas (Blegen 1928, pl. XXI, 4; Theochares 1953, fig. 15; Frödin and Persson 1938, fig. 172, 1 and 3; Mylonas 1959, fig. 166, 13). There are also a few impressions (Blegen 1928, fig. 91.1; Frödin and Persson 1938, figs. 160.2 and 172). It had at first been thought that these mainland finds were of Cretan origin, but the whole situation has been transformed by the find of a large deposit of sealings In the House of the Tiles (fig. 7.7), from the Korakou culture at Lerna. The complete absence of actual seals from the preserved remains at Lerna suggests that they may have been of wood, and were it not for this major find we should have no indication of the importance of seals and sealings on the mainland at this time. It may well be that seals were in frequent use at other sites as well, and perhaps also in the Cyclades and the eastern Aegean.

The main Lerna deposit (Heath 1958; Wiencke 1969) is slightly later than a further group found near the House of the Tiles. The main group consisted of fragments of 124 sealings, with the imprints of 70 different seals. Five different kinds of sealing operation are indicated by the impressions on the reverse of the sealings, which show imprints of poles from large boxes, of reeds, of the circular necks of jars, and of the mouths of jars.

The actual designs of the seals were predominantly continuous line motifs. Levi has commented upon the similarity in design with sealings found at Phaistos, suggesting that the Lerna seals might have been the work of Cretan craftsmen (1958b, 190). Mrs Sakallariou following a suggestion of Caskey believes that they may be of Cycladic work, together perhaps with those of Phaistos (Sakallariou-Xenaki 1961–62, 79). But to attribute these seals to overseas craftsmen may be to undervalue local potentialities. At present it seems safest to follow Heath’s view that they were the product of ‘an independent and perhaps local school of seal cutting’.

The main point here, however, is not the origin of this particular glyptic style, but the function of the sealing. The circumstances of the find, in the small Room XI of the House of the Tiles, is clearly very significant. This great building 25 m long and 11.7 m wide yielded few finds other than these sealings and some pottery; a mass of melted lead was also found with traces of burnt timbers in Room XII. Its size (pl. 20, 1; fig. 7.5) and the respect which was paid to the site in the period of the succeeding Tiryns culture (when it was covered by a low mound and building there was avoided) indicate its significance. Caskey has well said, with appropriate caution, that we are ‘probably justified in calling the House of the Tiles a palace, though with a clear admission that we have no certain knowledge of the political organisation which that word implies’.

This central building was preceded at Lerna by an earlier edifice, Building BG, belonging to a prior phase of the same culture. Built on a different axis, Building BG was itself 12 m wide and contained a great ceremonial hearth of clay (pl. 20, 3). This large building is described by the excavator as ‘a prototype and precursor of the later palace’.

These large central buildings at Lerna, together with the fortification wall, would in any case indicate some degree of central authority. The sealings give the strong presumption that some kind of redistribution of goods was taking place, although there is no suggestion that the central organisation was supporting full-time specialists. The existence of some ruler or chief, on whose authority dues were collected, or under whose patronage exchanges were transacted, seems indicated.

The important central building of Troy II and the Rundbau of Tiryns, whatever their precise function, are likewise indications of central organisation and probably of the rise of chiefdoms. We see, therefore, that the first palaces of Crete had precursors in several parts of the Aegean. And although the evidence is tenuous, the building remains preserved indicate, in Greece and the Troad, the emergence of a central organisation. The seals and sealings give an insight into the economic factors favouring this social and political development.

The evidence for hostility and for war in the Aegean, like that for wealth and hierarchy, first becomes convincing during the third millennium BC. This is clearly documented both by the evidence of weapons, and by the remains of defensive works.

FIG. 18.8 Warrior aristocracy: the Late Minoan ‘Chieftain’s Grave’ in the Zapher Papoura cemetery, with its long- and shortswords. Length of longsword, 96 cm (after Evans).

FIG. 18.9 Grave goods above the covering slabs of the ‘Chieftain’s Grave’ (after Evans).

No weapons, as distinct from projectiles for the hunt, have been found from the neolithic period. The baked clay slingstones commonly found in neolithic Greece may, of course, have been used in armed hostilities, just as we know them to have been in later times. The bow was discussed briefly in chapter 17: it remains perfectly possible, however, that the tanged points found on the Greek mainland and the Cyclades during the later neolithic were arrowheads. Several well-made flint spearheads from the late neolithic of Thessaly (Tsountas 1908, pl. 42, 14–18) are roughly contemporary with those from Saliagos, which are made of obsidian (Evans and Renfrew 1968, fig. 61).

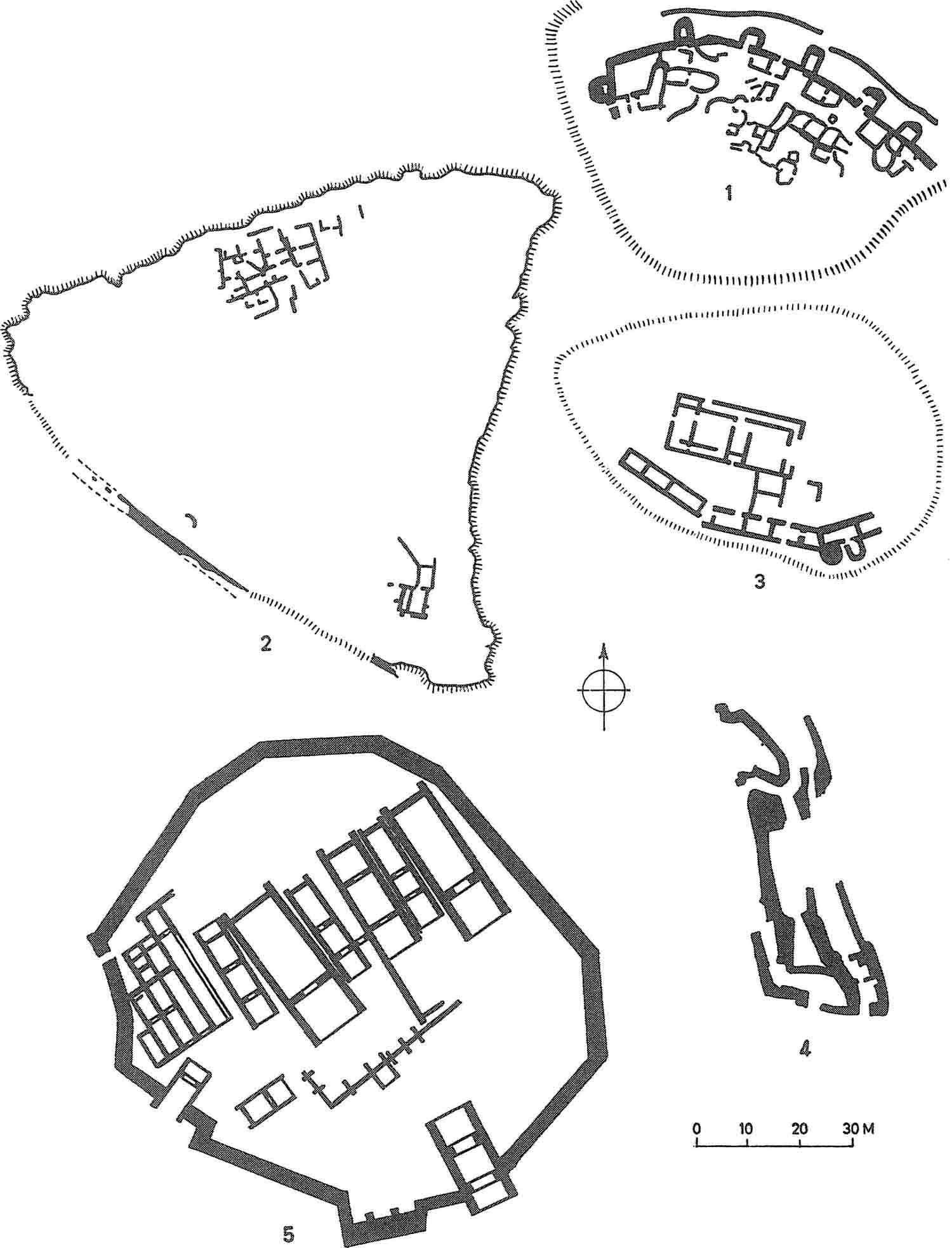

The practice of fortification can give a more reliable indication of inter-village or inter-regional hostilities. Nea Nikomedeia may conceivably have had some defensive works in early neolithic times (Rodden 1965, 84), while during the middle neolithic period two sites in Thessaly, Sesklo (Tsountas 1908, 75) and Magula Hadzimissiotiki, had enclosing walls possibly defensive in purpose, although this is not certain. Servia in Macedonia at about this time was surrounded by a ditch, possibly defensive in purpose (Heurtley 1939, 45). The outstanding example of a site apparently fortified during the neolithic period, although in the late phase, is afforded by Dhimini (fig. 18.13, 1). While less impressive in appearance on the ground than it appears in plan, the site has a central area enclosed by several lines of concentric circuit walls of stone. It is clearly the precursor of such early bronze age citadels as Troy. The concentric arrangement emphasising the significance of the central buildings contrasts markedly with the altogether democratic arrangement of the earlier neolithic villages. Fortification walls of stone were found also at Emborio in Chios in later neolithic levels.

These are the most important indications that life in late neolithic times may have been less peaceful than is often supposed. It is clear that while the range of weapons available in neolithic times was extremely limited, inter-village hostility at least may have been fairly widespread.

Weapons for hand-to-hand conflict were not made in the Aegean until the third millennium. Those of the huntsman, the bow and the spear, were probably also used in warfare, although the bow not very widely. A great pile of sling-stones was found at Panormos in Naxos outside the small fortified gate (Doumas 1964, pl. 484, b). The spearhead was now of bronze, but its pre-eminence as a weapon was replaced by that of the dagger. Indeed henceforward the spear is nearly always found accompanying a dagger. This is the case for the three graves in Amorgos where the spear has been found in good association (Tsountas 1898, Graves 12 and 14; Bossert 1954, cf. Dümmler 1886, pl. 1, 7 and 8) and for grave R 9 in Levkas (Dörpfeld 1927, pls. 62 and 63 a). The slots in their blades would have been of considerable aid in the halting to a shaft of wood (fig. 16.5; Bossert 1954, pl. 15, 4). The two weapons may together be regarded as constituting the equipment of the bronze age military man: if a single weapon was carried, it would usually be the dagger.

Henceforward the dagger, or its direct development, the sword, was the first and essential weapon. The existence of these sharp blades of bronze, stoutly hilted in wood, must have transformed hand-to-hand fighting, for until this time the basic weapon may well have been the wooden stave. The dagger’s great popularity is very clearly documented by the numerous finds from Amorgos (Renfrew 1967a, pl. 89), and especially by those in the Cretan tombs, where no fewer than 250 have been found. Although in many cases primarily a weapon, the dagger was a dual purpose object, serving also as a knife. Not until the late bronze age were these two functions clearly differentiated. Finds of knives are rare in the early bronze age (see chapter 16), yet there were more bronze knives (and more razors) in the rich late bronze age Zapher Papoura cemetery near Knossos than all the weapons there put together. It seems possible that most adult males in Early Minoan Crete were buried together with a dagger, and that this, particularly in the case of the short dagger of type III, served them in life also as a knife, and perhaps even as a razor. As we shall see the custom of burying every man with his dagger did not continue in Mycenaean times.

FIG. 18.10 Richly decorated golden hilt of the short sword from the ‘Chieftain’s Grave’ (after Evans). Pommel diam. 4.4 cm.

The evolution of the dagger to the long sword has already been touched on (chapter 16). The splendid swords of Middle Minoan Mallia, for example (fig. 16.6), were preceded by the earlier and less developed forms from Amorgos and the Levkas graves, where the hilt was sometimes encased in sheet gold.

The correlation between personal status and the possession of richly adorned weapons cannot be over-emphasised. The graves suggest that a fine weapon was an essential mark of status for any rich and important man. For their time the weapons of Levkas or Amorgos were remarkable enough, but they are insignificant beside the splendid Mallia swords. And they, in turn, cannot compete in splendour with the beautifully decorated dagger blades of Mycenae.

The defensive works in the Aegean during the third millennium (figs. 18.11 and 18.12) testify to the rise of militarism in the area. They culminate later in the great walls of Mycenaean Tiryns, in the splendidly fortified citadel of Troy VI and in the walled town of Phylakopi II. It is noteworthy, however, that no fortifications are found in Crete either during the third millennium or in the period of the palaces. This seems paradoxical in view of the quantities of weapons buried with the dead, for these can hardly all have been intended for use overseas. Nor do the geographical peculiarities of Crete explain why it lacked fortifications in the prehistoric period: in early Greek times civil strife was exceedingly common (Ormerod 1924, 143). Even the existence of a sea-going fleet, sufficiently powerful to eradicate pirates (a doubtful development at this time) would not prevent internal strife. Some further social factor may have done so; the agglomerate plan of Cretan buildings in the neolithic period already hints at some social organisation of individual settlements.

The fortifications of a few later neolithic sites in the Aegean have already been noted. The situation is not so very different in the Early Bronze 1 period. What may have been a defensive ditch is recorded from the Eutresis culture site at Perachora-Vouliagmeni, and similar defensive works are seen at Argissa in Thessaly. In the Cyclades the only settlement of the Grotta-Pelos culture for which possible fortification evidence has been found is Zoumbaria on Dhespotikon, but the wall there is not very impressive, and its dating is uncertain, since the cemetery was used also in Keros-Syros times.

Stone-built fortifications are well documented only in the eastern Aegean in the Early Bronze 1 period. Emborio in Chios had been fortified with stone already back in the final neolithic, although plans are not yet available. The extent of the defensive works is clearly seen only at Troy, where the first fortifications may already have had a gate on the south side (Mellaart 1959a, 133). In the middle Troy I levels (which in Aegean terms may already be on the border of the Early Bronze 2 period) the fortifications were extended to the south, with gates to the east and south-east. The fortifications at Troy formed a ring less than 100 m in diameter, so that the site was a citadel rather than a township.

Poliochni Blue (Poliochni II), at the beginning of the Troy I period, was also fortified, and the fortifications were extended and strengthened in succeeding periods. The town site of Thermi in Lesbos, like Poliochni, was unfortified in the first phase of its occupation but may have had defences during Thermi III (Lamb 1936a, 24). The fortifications of Town V (fig. 8.4) are probably to be set in the succeeding period.