During the neolithic period in the Aegean, many of the features observable in the succeeding early bronze age and developing to the full in the palace civilisations, made their appearance. Since it is a major theme of the present work that there is considerable continuity in the Aegean from the early neolithic period to the full development of civilisation, this neolithic background is very relevant.

The neolithic period of Greece which covered a span of at least 3,000 years has been divided by Weinberg (1942; 1965a) into three parts, early, middle and late. Of these, the early phase corresponds to Phase II of the sequence outlined in Chapter 4, and the middle and late stages to Phase III.

In the short outline which follows, these sub-divisions are considered in turn. A further phase, the final neolithic, is then introduced to fill the evident gap in the sequence between what is generally termed late neolithic in southern Greece and the early bronze age cultures, which developed several centuries later.

Evidence for the palaeolithic period in Greece has come from a number of sites in Thessaly, south Greece, and especially in Epirus (Weinberg 1965a; Higgs 1968). In two areas only have finds been reported which can be recognised as belonging to the neo-thermal period, and yet to antedate the introduction of farming.

The term ‘mesolithic’ is here avoided, being best applied to regions where the neo-thermal climatic changes had very marked ecological effects, transforming the subsistence patterns of the inhabitants. In the Old World, this may be seen in northern Europe, but the evidence for such a change is less marked in the Mediterranean region. At the Franchthi Cave in the Argolid an apparently continuous transition from the Upper Palaeolithic period to neothermal times has been observed in the stratigraphy (Jacobsen 1969). Before the first domestic animals, sheep and goat, appear in the record, red deer is the dominant faunal species. Sometime before 7000 BC, in radiocarbon years, fishing became important, and at this period obsidian was obtained from the Cycladic island of Melos. By about 7000 BC abundant sheep and goat remains, presumably domestic, are found, although without pottery This apparently aceramic neolithic phase is overlain by deposits with early neolithic pottery which appears by about 5800 BC. Early neothermal finds have been reported also from Thessaly, notably, at the site of Voivi (Theochares 1967).

An aceramic neolithic phase in mainland Greece is now attested also at Argissa Maghoula (Milojčić, Boessneck and Hopf 1962) and several other Thessalian sites including Souphli, and Sesklo (Theochares 1958; 1967). In each case, however, the excavated area is rather small and it is conceivable that pottery was already used in small quantities at some of these sites (Rodden 1970). The lowest level at neolithic Knossos with a date of 6100 BC (BM.124) is likewise without pottery. The grains from this site include emmer, naked hexaploid wheat, hulled barley and lentils (Evans 1964a, 140; 1968) to which can be added einkorn, millet, oats, vetch, peas and acorns for the corresponding Thessalian finds (J. M. Renfrew 1966). Domestic sheep, goat, cow and pig were kept at Argissa, as well as wild animals, and the same domesticates occur at Knossos. The rather similar proportions of these species at Nea Nikomedeia, which also resemble those seen later at Saliagos and Sitagroi, suggest that the relative importance of these animals may not have changed very significantly between the early neolithic period and the present.

The earliest dated pottery in Greece comes from Nea Nikomedeia in Macedonia with radiocarbon dates between 6200 and 5300 BC for the early levels. The red-on-white painted ware and indeed some of the small objects resemble finds in Anatolia (Rodden 1965), while the impressed ware and white painted ware has parallels in the Balkans. At present it seems safest to assume the arrival of the earliest farmers with their domestic sheep and goats and their domesticated cereals, emigrants from Anatolia. Similar finds have been made in Thessaly—the Proto-Sesklo culture. Further south it seems that there may be no painted pottery in the earliest phases, but in general the finds are similar to those of Thessaly. The houses at Nea Nikomedeia were rectangular in plan, between 8 and 11 m in length, built of posts and plastered pisé mud. As Rodden has pointed out, the open plan contrasts with early neolithic sites in Anatolia and compares rather with neolithic sites in Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria (fig. 5.1).

In Crete the earliest date for the pottery neolithic levels is 5620 BC (BM.272). The Cretan neolithic pottery is quite different from that of mainland Greece. Copper ores are already found in these early levels, and a curiosity is the baked mud brick used in house construction, together with the unbaked pisé or tauf (plastered mud) which was elsewhere more usual.

No early neolithic finds are known yet in regions of north Greece east of Nea Nikomedeia, or from west Anatolia. Only at the Aghio Gala cave on the off-shore island of Chios have finds been made which may date from this time (Furness 1956). Although no early neolithic finds have been made in the Cyclades, the island of Melos was certainly already being visited for its obsidian, which reached the Franchthi Cave before neolithic times, and Thessaly and Crete from the very beginning of the neolithic period

The neolithic occupation of Greece had thus begun by about 6000 BC, and using Weinberg’s convenient classification (and his radiocarbon dates for Elateia) the end of the early neolithic period may be set perhaps a little before 5000 BC (radiocarbon years).

The classic neolithic sequence in the Aegean is that of Thessaly, first established by Tsountas and conveniently revised by Milojčić, on the basis of his recent excavations (Tsountas 1908; Milojčić 1959). Tsountas’s Thessalian A, now termed the Sesklo culture, begins the middle neolithic of Thessaly. Although some authors have argued that a change of population took place at this time, there are elements of continuity in the pottery and figurines, and reservations are permissible concerning the suggested Anatolian or Near Eastern influences. In southern Greece the attractively painted ‘neolithic Urfirnis’ ware is common at sites like Franchthi, Hagiorgitika and Lerna, while in central Greece, at Elateia, the Proto-Sesklo tradition continues with some changes.

Towards the end of this period at Elateia and Corinth a new class of black-burnished pottery emerges, and with it appear the first arrowheads, and some curious four-legged vessels which are of great interest (Weinberg 1962). Very closely similar forms—and the shape is an odd one—have been found at sites of the Kakanj and Danilo cultures of Yugoslavia, and some contact between the two areas is likely.

At this time the village settlements, in Thessaly at least, were still on the open plan with separate house units. The houses were either square (as at Tsangli and Otzaki), or rectangular (as at Sesklo) and up to 20 m long.

The nature of the middle neolithic in north Greece has been clarified by the excavations at Sitagroi in east Macedonia. The first phase there has resemblances with the Vesselinovo culture of Bulgaria. Paradimi, further east in Thrace, has finds in its earlier levels which may be equated with the first and second phases at Sitagroi, including ‘black topped’ ware. Whether the similarities between the Sitagroi and Bulgarian finds at this time can be explained by Aegean ‘influence’ on the Balkans or vice versa, or perhaps Anatolian influence on them both, remains to be established.

The middle neolithic of Crete shows almost complete continuity with the preceding phases, to the extent that a quantitative analysis was needed to distinguish effectively between them (Evans 1964a, 203). The only clear contact with the remainder of the Aegean is established by the continuing presence of Melian obsidian.

The middle neolithic of west Anatolia is very little understood. The only well-stratified settlement is at Emborio in Chios: the succession there is discussed in the next section.

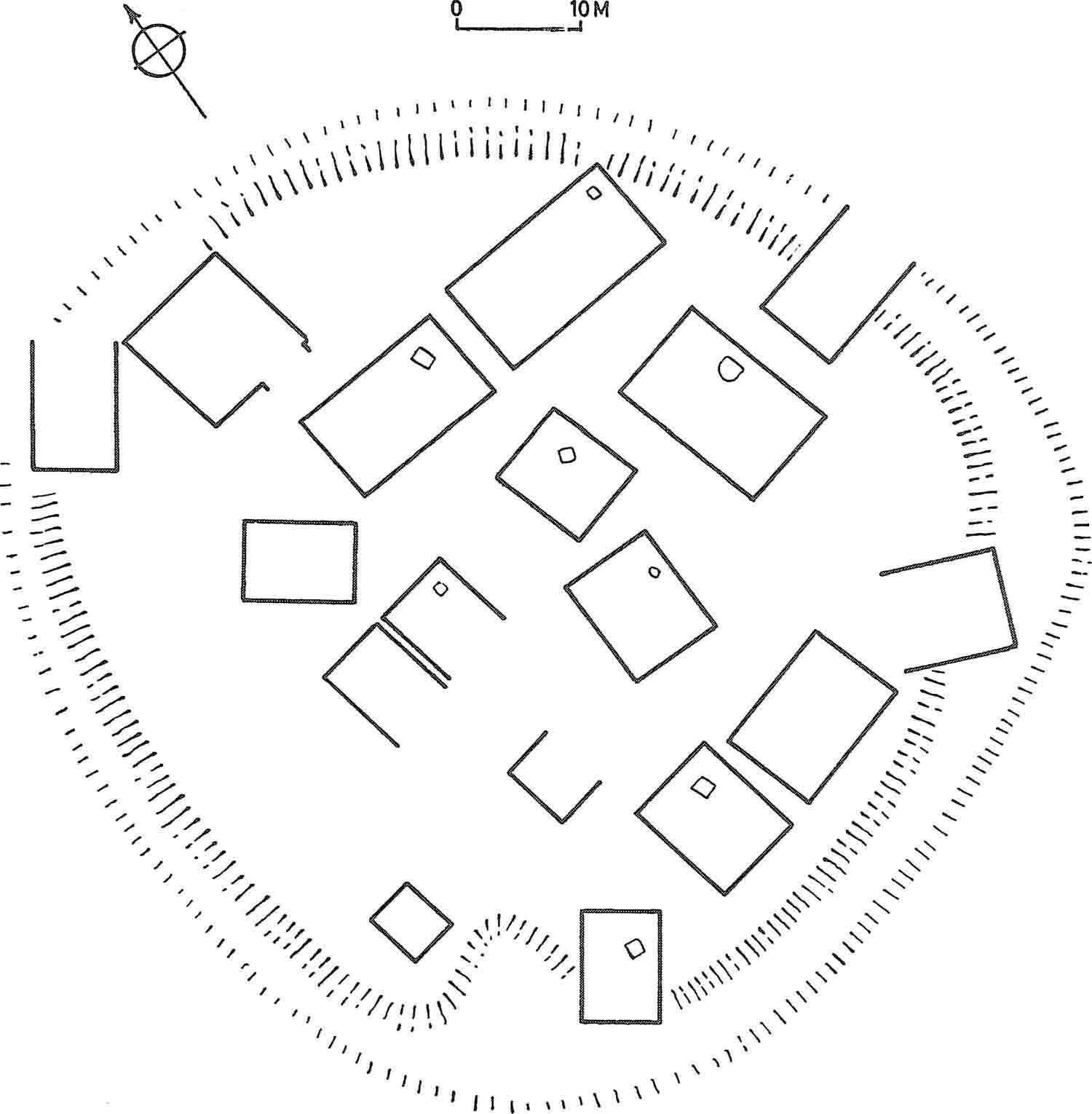

FIG. 5.1 Complete village plan of the later neolithic period. The Gumelnitsa culture site of Căscioarele in Romania, showing houses, in some cases with interior hearths. Later neolithic tell villages of north Greece were rather similar (after Dumitrescu).

The Cycladic islands were occupied during the later part, at least, of the middle neolithic period. Finds of the Saliagos culture have been made at the type site, and at Vouni, both in Antiparos (Evans and Renfrew 1968), at Mavrispilia in Mykonos (Belmont and Renfrew 1964) and at Agrilia in Melos (Renfrew 1965, 34). The culture is quite distinct from the other cultures of the period, although there are similarities with the later middle neolithic finds at Elateia. Radiocarbon dates set its duration between 4200 BC and 3700 BC. There is thus an overlap both with the Early Neolithic II of Knossos (3730 BC: BM.279) and the late neolithic Dhimini culture of Thessaly (3680 BC, cf. Milojčić in Germania 1961, 446). This is not so much an inconsistency as an illustration of the arbitrary nature of the division into ‘early’ ‘middle’ and ‘late’. These terms are used only for convenience and do not imply any very strict contemporaneity between areas.

The middle neolithic period may be said to cover, very approximately, in radiocarbon years, the fifth millennium BC.

By common consent the Dhimini culture, Tsountas’s Thessalian B, has long been taken to mark the late neolithic period. The classic Dhimini pottery itself, as Weinberg rightly points out, has held an exaggerated importance in the literature. Its bi- and trichrome spirals were at first thought to indicate some contact with the Danubian lands—for example with the Petreşti and Ariusd cultures of Romania. In fact it is limited in its distribution, and its local origins and development have been made abundantly clear in Milojčić’s recent excavations (1959). Quite which phase of the culture is dated by the radiocarbon determination quoted above has not been stated.

But the radiocarbon dates for the early bronze age Eutresis culture at Eutresis itself, 2492 BC (P.307) and 2496 BC (P.306), which like all the others may be much earlier in calendar years, suggest a much longer duration for this neolithic phase than is usually admitted. Since in Thessaly and Macedonia there is evidence for at least two culture phases in the later neolithic, it is proposed here to follow the implications of Milojčić’s excavations and to divide this rather long period into an earlier (‘late neolithic’) and a later (‘final neolithic’) phase. The term ‘final neolithic’, an improvement on a previous suggestion, ‘latest neolithic’ (Renfrew 1964, 119), has been proposed by Mr Bill Phelps on the basis of his study of the neolithic of southern Greece (oral communication, July 1968).

The late neolithic, whose duration may be set from c. 4000 BC or a little later (in radiocarbon years on the 5568 half-life) to around 3300 BC or a little later, is represented by matt-painted or polychrome wares over much of mainland Greece. Milojčić has shown that in eastern Thessaly these make their appearance before the classical Dhimini pottery with its elaborately painted spirals. He has divided this late neolithic period into four sub-phases. The best account of this period is still that given by Tsountas, and his finds reveal a very different settlement plan from the well-spaced rectangular houses of Nea Nikomedeia or the square houses of Tsangli (Wace and Thompson 1912, 115). The most important site of this period is Dhimini itself. With its circle of defensive walls (fig. 18.13, 1), its spacious courtyard and its megaron house, it represents a notable development. Indeed it seems that in the late neolithic period there may have been some general shift away from the open settlement plan.

The new matt-painted (i.e. lustreless) pottery is now widely found, together with polychrome ware. Weinberg seeks to explain the change in decorative style by influence from the Ubaid culture of Mesopotamia, but the arguments have not yet been presented in sufficient detail to carry conviction. Likewise there seems little need to derive the spiral decoration of Dhimini pottery from the Cyclades (Weinberg 1965a, 47), a suggestion certainly not compatible with the chronology put forward here.

In north Greece at this time, the long stratigraphy at Sitagroi (which is discussed in the next section) together with the radiocarbon dates suggest that the later part of Stratum II there and the earlier part of Stratum III belong to the late neolithic period.

There is little in the Cretan neolithic record to allow precise equation with other Aegean finds. Following the radiocarbon date of 3730 BC for the Knossian Early Neolithic II phase, Stratum IV, we may suggest that this, together with Stratum III and possibly Stratum II (Knossian Middle Neolithic) be equated with this phase.

In west Anatolia and the offshore islands, several of the finds described by Dr Furness (1956) belong to this time. Certainly one or more of the phases at Emborio (discussed below)—perhaps Stratum VIII—must do so. In the Cyclades, as we have seen, the Saliagos culture was well still under way at the beginning of this period. As at Dhimini a settlement enclosure was found at Saliagos rather than the open plan arrangement. Of its immediate successor we know nothing.

The final neolithic period of Greece is generally not well represented in the great tell sites, since often, as at Lerna or Knossos, these were levelled off during the early bronze age period. For this reason it has been possible to cast doubt on the stratigraphic reality of the Larissa and Rachmani phases of Thessaly which fall at this time, on the sub-neolithic of Crete and on other materials which can now be ascribed to this distinct phase. Without the evidence of radiocarbon dating it could be argued, as Weinberg does (1965a and b) that the late neolithic was of short duration, followed directly by the early bronze age. But the emerging pattern of radiocarbon dates, and recent excavations, present evidence for a period dating from c. 3300 BC to c. 2500 BC in radiocarbon years. Until very recently there has been a gap in the Aegean radiocarbon dates at the fourth millennium BC but this gap is being filled, as it becomes clear that there were at that time prehistoric cultures in every region of the Aegean, of which we know as yet rather little.

Excavations in recent years at five sites do give further evidence for the reality of this period. At Emborio in Chios and Sitagroi in east Macedonia there is a long transition from neolithic to early bronze age. At Eutresis recent excavations have yielded clear evidence for a phase preceding ‘Early Helladic 1’. And Milojčić’s work at Otzaki in Thessaly points in the same direction. And finally, in the Cyclades, Professor Caskey’s excavations at Kephala give a homogeneous assemblage—no problems of stratigraphy arise—which has links both with the Grotta-Pelos culture of the Cycladic early bronze age and the final neolithic of Sesklo and Attica.

At present then it seems likely that the duration of the final neolithic period, expressed in radiocarbon years, is from c. 3300 BC to c. 2500 BC. In calendar years this should give an approximate duration of c. 4100 BC to c. 3200 BC. It was a time of considerable cultural diversity in the Aegean.

Much of the material classed by Tsountas in his period 3 (bronze age) succeeding the Dhimini period cannot today be regarded as bronze age in date. This applies to his Γ1α and Γ1β ceramic styles. At Rachmani, Wace and Thompson distinguished a stratum with crusted ware between the Dhimini and bronze age strata (1912, 31). At Larissa Grundmann excavated a group of black burnished pottery whose close position has been clarified by Milojčić’s excavations at Otzaki (Milojčić 1959, 24). That this does represent a distinct chronological phase is confirmed by the cemetery at Souphli (Biesantz 1959, 70), where several vessels were found, none of them like those of the Dhimini period.

In general the signs so far are scanty although they are sufficient to corroborate the view of Milojčić rather than that of Weinberg, who would prefer to conflate the late and final neolithic phases, allowing them to overlap with the early bronze age. At Rachmani, however, one house, House Q, of apsidal form, gave a complete assemblage of finds, including abundant pottery with crusted-paint decoration (Wace and Thompson 1912, 31–34; 37–40; 43, 53). These offer an entirely different impression from the finds of the preceding Dhimini period, and different again from those of the early bronze age. House Q at Rachmani has yielded the most convincing assemblage available of the Thessalian final neolithic.

The neolithic of southern Greece is at present being studied by Mr W. Phelps. It will be sufficient therefore to mention three sites important at this time for their Aegean connections.

Eutresis, first excavated by Miss Goldman, in 1924–27, was re-excavated in 1958 by Professor J. L. Caskey and Mrs Elizabeth Caskey. The pottery found was divided into groups of which I and II precede the early bronze age levels, groups III and IV are assigned to the Eutresis culture (Early Helladic I) and groups VI to VIII to the Korakou culture (Early Helladic II). Group II in particular contained a heavy slipped and burnished ware not known in the late neolithic period (Caskey and Caskey, 1960, 134). We shall see below that this can be compared to both Kum Tepe lb finds and the Grotta-Pelos finds of the Cyclades. It may be set, therefore, towards the end of the final neolithic.

Secondly, the pattern-burnished ware found at Aegina must be mentioned. Unfortunately, very little of the early material from Aegina has been preserved, and Welter’s finds were notably ill-published. It has not been possible to reconstruct shapes—the published reconstructions must be viewed with suspicion (Welter 1938). But in fabric and style the material resembles the finds from Kephala in Kea, which are described below. Recently at Velatouri near Thorikos in eastern Attica, an important deposit of final neolithic material has been found, with pattern-burnish ware closely resembling that of Aegina and Kephala (Servais 1965, 24–27). Among the forms open bowls again predominate.

Finally, there are important finds excavated in the Agora in Athens, which are under study by Mrs Sarah Immerwahr. They are likewise analogous to the finds from Kephala in Kea. They include pattern-burnish ware, ‘coal-scuttle’ fragments comparable to the Sesklo coal-scuttle (Tsountas 1908, p1. 16, lower) and a clay figurine head with tilted face. A rock-cut shaft tomb at the Athens Agora (fig. 7.6; Shear 1936, fig. 18) contained a bowl on a ring foot which resembles a find from Kephala (Caskey 1964b, p1. 47, f.). The close resemblances suggest that we may speak of an Attica-Kephala culture during the final neolithic. The mainland finds of this culture are at present scanty, but the impressive assemblage at Kephala itself establishes its identity and homogeneity.

The long duration of the later neolithic of Greece, and the reality of this final neolithic period, have been clearly documented by the finds at Sitagroi in east Macedonia. The stratigraphic succession there is a very long one, extending through a depth of deposits of nearly 11 m.

The lowest levels, which have finds resembling the Vesselinovo culture of Bulgaria are of middle neolithic date, since occupation began around 4600 BC in radiocarbon years. In Stratum II are dark-on-light painted wares which suggest comparison with later Sesklo and Dhimini pottery of Thessaly. Stratum II belongs to the earlier part of the late neolithic period.

Stratum III at Sitagroi contains two painted ceramic fabrics—black-on-red, and graphite-painted wares. The graphite-painted pottery very closely resembles finds of the Maritsa and Gumelnitsa cultures of Bulgaria and Romania. In both areas we see the same pottery shapes and the same curvilinear decoration. The numerous terracotta figurines and some of the small objects, such as terracotta furniture, support the connection. The abundant finds of bracelets of the shell Spondylus gaederopus suggest that this may have been one of the key supply points for the Balkan Spondylus trade. Small objects of smelted copper are frequent, and a gold bead was found. There was, of course, a flourishing metallurgy in the Balkans by this time. The stratigraphy and the radiocarbon dates indicate that the occupation of Stratum III began during the late neolithic period (well before 3300 BC in radiocarbon years) and continued into the final neolithic. At present it is not certain whether or not there may have been a break in occupation at the end of Stratum III. But the elements of continuity which exist between these finds and those of Stratum IV above seem rather to argue against a hiatus.

The pottery of Stratum IV is very different in character, being entirely without painted decoration. It is dark and well burnished, and occasionally with a little grooved decoration. The most striking form is the shallow bowl with high handle which is seen in Early Thessalian I (Milojčić 1959, fig. 21.11–13). The shape is seen already, although in a painted fabric, in the Thessalian final neolithic (Wace and Thompson 1912, 33, fig. 14). Radiocarbon dates for Stratum IV of 2440 BC and 2360 BC (BM.773 and 782) set it towards the end of the final neolithic and at the beginning of the early bronze age, broadly contemporary with the Eutresis culture of southern Greece but earlier than Troy I.

The final neolithic of east Macedonia thus covers the transition from a typically ‘chal-colithic’ culture, with painted pottery and numerous figurines, to a rather more sober assemblage, with plain burnished pottery, which seems to herald the early bronze age of this region.

The clearing of the tell mounds at Knossos and Phaistos at the beginning of the First Palace period (Middle Minoan I) severely truncated the earlier succession there. For this reason Early Minoan levels are rather poorly represented at Knossos, and Doro Levi, on the basis of his Phaistos findings, has been able to deny altogether the existence of an Early Minoan period (Levi 1964a; 1964b).

There is evidence to suggest that the latest neolithic deposits were likewise disturbed. The ‘sub-neolithic’ material, found elsewhere in Crete, has often been considered merely an impoverished contemporary of Early Minoan I. But I have argued elsewhere (1964, 118) that this is an assumption which unwarrantably establishes a hiatus between the Early Minoan and its neolithic predecessor: most of the so-called ‘sub-neolithic’ material would be better described as final neolithic in the sense established here.

I would like to suggest, therefore, that Stratum I at Knossos (Evans 1964a, 225) (Knossian Late Neolithic), the neolithic strata with painted ware at Phaistos (Levi 1958a, fig. 202) and the ‘sub-neolithic’ finds from Partira, the Eileithyia Cave and Phournoi (Renfrew 1964, 118), be together assigned to this at present hypothetical final neolithic.

While at Eileithyia there is also painted ware of the Early Minoan I and Early Minoan II periods, at Partira there is absolutely none, and this deposit may then be considered a pure one. The suggestion, therefore, is that these ‘sub-neolithic’ (i.e. final neolithic) deposits bridge the gap between the late neolithic deposits of Knossos and especially Phaistos and the Early Minoan I finds such as those of Lebena or the Early Minoan I well at Knossos. Two Eileithyia vases (Renfrew 1964, pl. E’, 1) compare with finds from the neolithic deposit of Corridoio VII3 at Phaistos (Levi 1958a, fig. 196 and 167), so that the finds in the Eileithyia Cave do indeed reach back to the later neolithic as well as forward to the early bronze age.

The principal forms of this Cretan final neolithic are the two-handled jar (Renfrew 1964, pl. E’, 3, 1) which may be regarded as a prototype for the Early Minoan I shape (Alexiou 1960, fig. 20; Xanthoudides 191, fig. 6); the bowl with high horn handles (Renfrew 1964, pl. E’ 4, 1); the suspension pot with lid (Renfrew 1964, pl. E’, 3, 2) and the bowl, sometimes on a ring base (Renfrew 1964, pl. E’, 4, 3) or with a small spout. Thumb grip handles are also seen, intermediate perhaps between the neolithic examples at Phaistos (Levi 1958a, fig. 196) and those still found in Early Minoan I (Alexiou 1951, pl. IΔ’, fig. 1; Xanthoudides 1918, 153, fig. 10.81). There is a prototype also for the Early Minoan handled cup (Renfrew 1964, pl. E’, 4, 2). Although it would be possible still to interpret these similarities as indications of contemporaneity, it seems preferable to see them rather as demonstrating continuity.

There is from Crete so far only a single radiocarbon date from the period of the final neolithic, of 2550 BC (Sa 241). The sample is from an unspecified cave with ‘late neolithic’ sherds. However, the date of 3730 BC (BM.279) from the late neolithic Stratum IV at Knossos reminds us that Stratum I there, and possibly Stratum II also, must fall within the span of the Aegean final neolithic.

Many ‘late neolithic’ finds have been made in Samos, Kalimnos, Chios and other islands of the eastern Aegean (Furness 1956). Although not well stratified, much of this material may fall within the span of the Aegean final neolithic, as also the finds from Beşikatepe.

At Kum Tepe also in the Troad, pottery was found clearly earlier than that of Troy I (Koşay and Sperling 1936). This does not in itself determine a final neolithic date, since the first settlement at Troy may not have begun so early as the Eutresis culture (Early Helladic I) or Early Minoan I. But it seems likely that Kum Tepe was occupied already in the later part of the final neolithic period.

The same observations hold for the site of Poliochni in Lemnos (Brea 1964, pl. I to VIII). The finds of the ‘blue’ period there are generally set contemporary with the early phases of Troy I, so that the preceding ‘black’ period should then antedate Troy. The finds from this period may be contemporary in part with those of Stratum IV at Sitagroi, although there is no great resemblance between the finds from these two sites. They fall towards the end of the final neolithic period.

Radiocarbon dates from Beycesultan are relevant here: there is a date of 3014 BC (P-298) for Late Chalcolithic I there (Beycesultan XXXVI) and of 2740 BC (P-297) for Late Chalcolithic III (Beycesultan XXVIII). The second of these dates, for Late Chalcolithic III, should be prior to the Late Chalcolithic IV, set by Mellaart as contemporary with Kum Tepe lb and Poliochni ‘black’ (Lloyd and Mellaart 1962, 112). On this basis most of the Beycesultan ‘Late Chalcolithic’ would be contemporary with our Aegean final neolithic. Mellaart (1970) has recently modified his original views, but these relationships seem plausible ones. They would lead us to set the beginning of Poliochni ‘black’ and of Kum Tepe around 3600–3500 BC in calendar years.

The key site for the eastern Aegean at this period is Emborio in Chios (Hood 1965a). The long stratigraphy at this site, as yet incompletely published, gives a full record for the later neolithic and early bronze age development, much as does Sitagroi in east Macedonia.

The lower strata, X and IX, have points of similarity with the finds from the Aghio Gala cave in Chios (Furness 1956) on the one hand, and possibly with Saliagos (Evans and Renfrew 1968, 90) in Antiparos on the other. Most of the pottery is plain and smooth: the bowls have rims with a thin profile. Writing in 1965 it was possible to suggest a date of about 4500 BC (in radiocarbon years) for the beginning of Emborio X (Renfrew 1965, fig. 13). The Saliagos radiocarbon dates serve to support this view (Evans and Renfrew 1968, 90), which would put Emborio strata X and IX in the later part of the middle neolithic period of the Aegean. Emborio Stratum VIII apparently follows without discontinuity upon Stratum IX. The incised ware first seen in Stratum IX remains popular, and a black pattern burnish fabric is now common. This phase must belong in the late neolithic period of the Aegean, as here defined.

FIG. 5.2 The evolution of the burnished bowl in Chios. The Roman numeral signifies the phase at Emborio; A.G. indicates Aghio Gala. Scale c. 2:5.

FIG. 5.3 Aegean later neolithic bowls, no. 3 pattern-burnished. 1–4, Kum Tepe la; 5–10, Kum Tepe lb; 11, Kum Tepe le; 12–13, Lerna II; 14–15, Poliochni I. Scale c. 2:5.

The assemblage of Emborio VII and VI shows features, especially in the bowls, which relate it closely with Kum Tepe lb and with Poliochni. As discussed in chapter 10 the rolled rims are a common feature of most of these bowls, although there are differences in the shape and position of the tubular lug handles. In Stratum VII the black pattern burnish ware is less common, but a separate and distinct red fabric is seen. Strata V and IV at Emborio may be equated with the Troy I culture. A new, rather heavy, incised style is seen, which has been likened to that of the Troy I period at Poliochni. It finds resemblances also in the Yortan culture and in Aegina. Numerous copper (or bronze) objects are now found. There is a radiocarbon date of 2025 BC (P-273) for the destruction level of Stratum IV, the equivalent of a date in calendar years of about 2550 BC.

A fuller consideration of the Emborio finds must await the publication of the material. But already it is clear that strata VII and VI are to be assigned to the Aegean final neolithic. They relate to Kum Tepe la and lb, and Poliochni ‘black’. Perhaps the most exciting feature of the site is that the final neolithic culture there seems to develop steadily and without interruption from middle and late neolithic predecessors, so that the evolution of the final neolithic of the eastern Aegean is clarified.

The middle-to-late neolithic Saliagos culture had no obvious immediate successor yet recognised from the archaeological record. But two culture groups may be discerned in the final neolithic. One of these, the Grotta-Pelos culture, continues without interruption into the Early Bronze I phase in the Aegean. Its domestic pottery shows close similarities with the Kum Tepe lb finds, and with some of those of Emborio VII and VI. Despite these final neolithic origins, the Grotta-Pelos finds are discussed in chapter 10.

The second culture group in the Cyclades takes its name from the site of Kephala (Caskey 1964b). A rather poorly preserved settlement on the headland there yielded pottery, indications of metal smelting and a radiocarbon date of 2876 BC (P-1280), corresponding to a calibrated date of c. 3500 BC. The Attic-Kephala culture, probably contemporary in part with the early Grotta-Pelos culture, belongs to the Aegean final neolithic.

The most important and exciting find at Kephala was the cemetery of small built graves. They were circular or rectangular in shape, consisting of small flat stones, and containing several burials each, as well as a few grave goods. Some pithos burials of children were also found in the cemetery. Amongst the grave goods were several establishing so close a contact with certain sites in Attica that the term Attic-Kephala culture has been proposed for this assemblage (Renfrew 1965). The most important of these is the pattern burnished pottery, which is of red fabric, with the burnished and non-burnished lines of approximately equal width (Caskey 1964b, pl. 47, h and i). This distinctive style is seen also at Aegina and Velatouri near Thorikos (Servais 1965, 24–27) as well as Prosymna (Blegen 1937, fig. 635), Corinth (Robinson and Weinberg 1960, 250) and Askitario (Theochares 1954a) and the Agora at Athens. A further link with Athens is provided both by fragments there of the ‘coal-scuttle’ vessel seen at Kephala (Caskey 1946b, pl. 46, e and f) and by the characteristic figurine heads of clay (Caskey 1964b, pl. 46, c and d) with prominent noses. A similar ‘coal-scuttle’ was found also in the final neolithic levels at Sesklo (Tsountas 1908, pl. 16, lower).

The Attic-Kephala culture, like the Attic-Cycladic Mischkultur of the early bronze age is restricted to Attica, Euboia and the north-western Cyclades. It clearly belongs to the final neolithic of the Aegean.

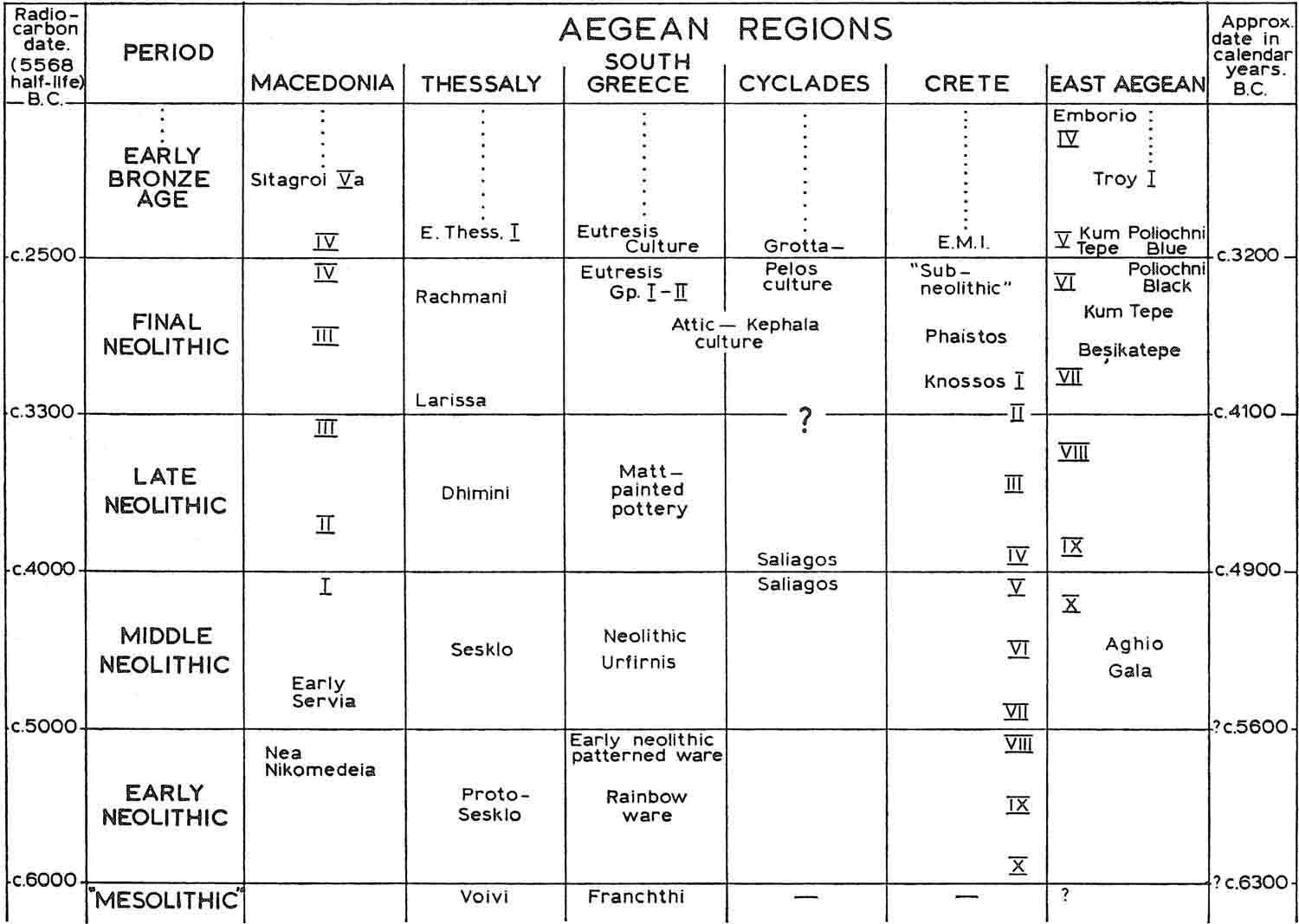

On the basis of the relationships noted, and of the radiocarbon dates, a simplified chronological table may tentatively be proposed to clarify the position of the final neolithic cultures in the various regions of the Aegean (Table 5.1).

TABLE 5.1 Culture sequence and chronology of the Aegean neolithic.

Many relationships expressed in this table are hypothetical. But it does serve to bring out the reality of this final neolithic period in each of the regions under consideration.

Despite the great variety of these finds, a number of similarities can be indicated which link together some of the different regions in the final neolithic. The Thessalian finds, which are supplemented by others elsewhere, suggest that fruits (figs, grapes, almonds and a new variety of pistachio) were now more systematically collected, while pure crops, of a single species, replaced the mixed crops of the earlier period. The three classes of domestic animal, sheep/goats, cattle and pigs, naturally do not change, although pigs possibly increase in importance at the expense of sheep and goat, almost to equal these in numbers.

As in the succeeding early bronze age, the Cyclades occupy a central and important position. The parallels of the Grotta-Pelos culture, which certainly began towards the end of the final neolithic period are considered in a later chapter. Despite the various points of contact which are now seen—between Kea and Attica for instance, or the Cyclades and north-west Anatolia—the Aegean was certainly far from a unity at this time.

The widespread distribution of pattern-burnish decoration on pottery has sometimes been taken as an indication of such unity (Fischer 1967), but the effect is illusory, for in reality the various regional styles were very different one from another. The Aegean pattern burnish of the late and final neolithic (plus the early bronze age in the case of Crete) may be divided into at least five categories (fig. 5.4).

I. The Attic-Kephala Style. As already described, the fabric is generally red, while faulty firing or subsequent reduction will account for one or two black pieces in Aegina. The lines are very thick. Final neolithic of Attica and the north-western Cyclades.

II. The Pyrgos Style (fig. 6.1). Black fabric with thin burnished lines, but without a reserved arrangement. The decoration is on the outside. The shapes are very distinctive—chalices and pyxides—and the style is limited to Crete, where it was first recognised at Pyrgos (Xanthoudides 1918). The recent excavations at Lebena define it as Early Minoan I.

III. The Beşkatepe Style (fig. 5.3, 3). Usually black fabric, overall burnish outside, reserved panels inside crossed with a network of narrow lines (Lamb 1932). Also at Samos and Kum Tepe la. East Aegean final neolithic.

IV. The Mainland Style. Categorised by Wace and Thompson, following Tsountas, as Fiai. It does not form a homogeneous group, and probably includes several independent traditions. At times one feels that the decoration arises almost spontaneously as the pots are being burnished. In general the fabrics are black, sometimes with a high Larissa-ware lustre. Find spots include Tsangli, Messiani Maghoula, the Larissa region, Elateia, Orchomenos, Corinth and Varka Psachna in Euboia. Final neolithic of Thessaly and central Greece.

FIG. 5.4 The regional groups of pattern burnish pottery in the later neolithic and early bronze age of the Aegean. Group I, pattern burnish pottery of the Attic-Kephala culture; Group II, Pyrgos ware; Group III, Beşkatepe ware; Group IV, pattern burnish wares of central and northern Greece; Group V, Chios pattern burnish ware (see also notes to the figures).

V. Emborio. The pattern-burnish ware of Emborio has already been mentioned. Although the arrangement of lines resembles the Attic-Kephala style, they are thinner and the lustre is less rich. The fabric is generally grey black, and open bowls are not found, the commonest form being a collared jug. Another variety is also found at Emborio with red fabric, different shapes, and a tendency to leave reserved parallel lines. East Aegean late neolithic and final neolithic.

Doubtless other varieties occur. The aim of this list, however, is not to give a complete survey, but simply to show how numerous occurrences of this technique in fact are, and how meaningless must be a correlation on the simple basis of pattern burnish alone. It is certainly noticeable that the style is chiefly used in final neolithic times, but it is then that burnishing itself most widely occurs, perhaps as a result of the decrease in popularity of painted decoration. This fashion for burnishing may perhaps be due to the operation of some widespread causal influence, but the presence of pattern burnishing itself is no proof of a connection between particular instances.

Among the widespread features at this time, the decline in painted ware in the Aegean is indeed very noticeable. In Macedonia painted ware disappears altogether, and in Thessaly It is uncommon. Of course it was always absent at Knossos, and rare in the eastern Aegean.

The emergence of new burial practices also requires comment. Simple crouched burials, sometimes with sparse grave goods, are found from the early neolithic period onwards (Rodden 1962; Heurtley 1939, 54). A burial from pre-neolithic neothermal times was found in the Franchthi Cave (Jacobsen 1969). In the middle neolithic period a small oval cist grave was found at Hagiorgitika (Weinberg 1965a, 36), and at Prosymna several grave pits with grave goods and the bones, perhaps cremated, of the deceased were found (Blegen 1937, 25–8). This Is In effect the earliest cemetery yet found in Greece, unless the burials within the settlement at Nea Nikomedeia are so considered. At Lerna a child-burial in a beaker was found (Caskey 1957, 159) and at Rachmani a similar child-burial (Wace and Thompson 1912, 244). These are all sporadic occurrences and do not compare in significance with the two final neolithic cemeteries now known. At Souphli what may reasonably be termed an urnfield cemetery was found. At least seven black burnished jars, assignable to the Larissa period, contained the cremated bones of the dead (Biesantz 1959, 70). In two cases the burial was accompanied by a further pot. These constitute the first well authenticated cases of urn burial and of cremation In Greece—perhaps the first in Europe. The Kephala finds which include pithos burials, constitute the first cist cemetery, and document the earliest multiple burials known from the Aegean. Of course, at lasos on the west Anatolian coast, both round and rectangular cist graves have been found (Levi, 1962), but these and the cist and pithos burials described by Özgüç from Anatolia (1948, 22) are of early and later bronze age date. Our first evidence for burial in cemeteries thus comes from the final neolithic; and so far there is no case for deriving the custom from overseas.

Finally, the notable scale of the final neolithic finds at Knossos, despite the postulated destruction of their uppermost levels, must be mentioned. The extent of the site may have been some seven acres. The settlement there seems to have been on the agglomerate plan, with numerous rooms juxtaposed and few isolated buildings (fig. 6.4, 1; Evans 1921–35, II, 14). This gives a very different picture from that of the individually situated houses in the villages of central and northern Greece and the Balkans (fig. 5.1). Whether or not such a layout is seen in the earlier periods is uncertain. But the abandonment of the open plan at Dhimini in the late neolithic and at Knossos by the final neolithic is clearly of significance.

From these rather fragmentary indications we can see that the neolithic in Greece was not a static period, marked only by changes in pottery style. Significant developments occurred in agriculture, settlement organisation, burial and technology. It is against this background that the innovations of the third millennium BC, the early bronze age, must be judged. The final neolithic period is admittedly little understood as yet: it may be that in it lies the key to our comprehension of many of the subsequent early bronze age developments.

This very brief sketch of the neolithic period sets the scene, as it were, for the consideration of the culture sequence in the third millennium. And it is to these cultures in the various regions of the Aegean that we must now turn.