As in Crete, and elsewhere in the Aegean, the early bronze age of southern and of central Greece is a time of awakening. At its beginning, at the end of the final neolithic period, the picture we have of the way of life is not greatly different from that of two or three millennia earlier. By its end there are clear indications of centralised organisation and of craft specialisation, especially in metallurgy, which herald the emergence of civilisation.

Civilisation, as documented by the formation of important religious or secular centres (such as palaces) and by writing did not, however, appear on the mainland at the close of the Early Helladic period. The impression which we have of the way of life of the middle bronze age is at present one of consolidation rather than dramatic change. And indeed while the Shaft Graves at Mycenae at the beginning of the late bronze age show enormous wealth, and its concentration in the hands of warrior princes, actual palaces are not well documented until the Late Helladic III period, from about 1400 BC.

None the less, the Early Helladic period, as in contemporary Crete, was one of major change, when the foundations of civilisation were being laid. The notion that Early Minoan Crete alone was responsible for the principal advances of the time is belied by an impressive array of finds in other regions. These will be surveyed in outline here. But first again it is necessary to define the cultural and chronological divisions employed.

Wace and Blegen (1918) defined the Early Helladic period as broadly contemporary with the Minoan early bronze age. It was sub-divided in 1921 by Blegen into three groups to which periodic names were attached. They were subsequently redefined by Caskey (1960a). As originally suggested in 1965 (Renfrew 1965), for the reasons given above in chapter 4, I propose to use culture names for these bodies of material.

The geographical boundaries of the region in question are defined for us by the areal extent of the culture under consideration. Clearly the distribution of these cultures was not a static one, but during the Korakou period at least it seems to have included all of the Peloponnese, Attica, Euboia and much of Boeotia, extending westwards to the Ionian Islands (cf. the distribution of ‘sauceboats’ in fig. 18.12).

The Eutresis culture, a material assemblage first recognised by Blegen at Korakou (and designated Early Helladic I) remains disappointingly ill-documented today. Hetty Goldman’s stratigraphy at Eutresis was largely confirmed by J. L. and E. G. Caskey at that site in 1958. In the earliest levels they unearthed final neolithic material (Groups I and II). Group I contained typical late neolithic pottery including matt-painted ware with characteristic shapes (Caskey and Caskey 1960, fig. 4, upper), together with fine black burnished ware and coarse ware, and a neolithic clay figurine.

Eutresis Group II contains these same fabrics, together with a new one, the Caskeys’ ‘heavy slipped and burnished ware’, a characteristic fabric which as suggested in chapter 5 may be regarded as belonging to the final phase of the south Greek neolithic. A pintadera (stamp seal) was also found in this level.

With material of Group III are found the first buildings and pavements, and the red-slipped ware, singled out by Blegen as characteristic of Early Helladic I, is now seen (Goldman 1931, pl. v). The jug, or perhaps more accurately one-handled cup (Caskey and Caskey 1960, 140 and pl. 46), occurs with bowls and jars, and the neolithic wares almost disappear. Burnished monochrome ware, light coloured plain ware and coarse ware are also present.

In Groups IV and V the same ceramic wares are seen, with one-handled cups, bowls, jars, ‘spoons’ (little one-handled bowls or ladles) and the spout of an askoid vessel. Incised fine ware is a new element, with a fabric resembling the heavy slipped and burnished ware of Group III. The incisions are often filled with white colouring matter. This interesting incised pottery is mentioned again below and in Appendix 2.

The distribution of the culture is not altogether clear since it has been identified in homogeneous deposits only at Korakou, Eutresis, Palaia Kokkinia and Perachora-Vouliagmeni. The red-slipped ware has been found, however, at several sites in Attica, Boeotia and the north east Peloponnese, notably Zygouries, Asine and Corinth, and at Emborio in Chios. Isolated finds in the southern and western Peloponnese occur at Asea and Teichos Dhymaion, and at Kastri in Kythera. French also includes many Thessalian sites in his useful distribution map of this ware (French 1968, fig. 71).

The Korakou culture, or ‘Early Helladic II’, is well known from many south Greek sites for its characteristic thin-walled pottery, with lustrous surface, known as Urfirnis. It occurs in readily recognisable shapes, notably the ‘sauceboat’ (fig. 7.1, Caskey and Caskey 1960, pl. 49), the jug with long thin neck (ibid., pl. 51, VIII.28), the askos (ibid., pl. 49), and the little footed bowl (ibid., pl 50). Pyxides are also found (ibid., pl. 50) usually of lentoid shape. The stratigraphic succession is again well seen at Eutresis, where Groups VI–VIII provide ample material of this culture.

Burnished ware with incised and stamped decoration is still found, often with white Infilling (fig. 11.6). An important feature of the Korakou culture, not adequately represented at Eutresis, is pottery with painted decoration. For this we must turn to what is certainly the most important settlement yet excavated of the culture: Lerna, Stratum III. Here many of the characteristic Urfirnis shapes are found decorated with glossy dark paint (Caskey 1960a, 292): decoration and shapes are closely similar to those of the Keros-Syros culture of the Cyclades. The various important finds of this culture are summarised below. Its distribution is wide, covering the Peloponnese, Attica, Euboia and central Greece (Boeotia, Lokris, Phokis) extending west to Levkas. Most of the Korakou culture settlements suffered destruction by fire at the end of the period (although not Eutresis or Orchomenos), and Caskey has sought to connect this with the coming of a new population to the area (Caskey 1960a, 302).

FIG. 7.1 Pottery ‘sauceboats’, the Leitform of the Korakou culture, from Lerna (after Caskey).

At Lerna the important Korakou culture of Stratum III was overlain by deposits of Stratum IV with a different cultural assemblage. This made it possible for Caskey to define precisely, for the first time, the ‘Early Helladic III’ culture (Caskey 1960a, 293 f.), here termed the Tiryns culture. The term Early Helladic III, as used by all writers prior to Caskey’s 1960 article, must be interpreted with caution, as it nearly always includes material of the Korakou cultural assemblage. Whether this is due to the difficulty of distinguishing the strata at some sites, or to the actual contemporary use of the material, is not yet clear. At any rate there is a clear separation at Lerna.

The two new and characteristic wares are dark-on-light patterned ware, and the light-on-dark ware with similar shapes and motifs known as Aghia Marina ware. The new motifs are entirely characteristic (Müller 1938, pls. XXXVI–XXXVIII), so much so that a single sherd from Kritsana in Macedonia, and another from Pelikata in Ithaca, are at once recognisably of this ware (Heurtley 1939, 170, fig. 43 and 1934–35, fig. 20; Caskey 1964a, 23). The most important new shapes are the two-handled tankard (fig. 7.2; Goldman 1931, pl. VIII), small cups (Caskey 1955a, pl. 21, e–g) nicknamed ‘ouzo cups’, wide cups with out-turned rim (Goldman 1931, pl. IX, 4), two-handled bowls (Caskey 1960a, pl. 70, i), and various jar shapes (ibid., pl. 70, j).

FIG. 7.2 Tankards of the Tiryns culture, from Orchomenos and Tiryns, painted with light-on-dark, and with dark-on-light decoration (after Schachermeyr).

An unexpected discovery at Lerna was that some of the pottery was made with the use of the potter’s fast wheel (ibid., 296 and pl. 70). This innovation, and the introduction of the handsome well-made grey pottery known as ‘Minyan ware’ were formerly thought to be distinctive signs of the Middle Helladic period in Greece. Both are now seen at Lerna IV with materials of the Tiryns culture. Incised and stamped ware are still found, and corded ware sherds (decorated when soft by the impression of twisted yarn) have been found at a few sites (Goldman 1931, 122, fig. 169).

The distribution of the Tiryns culture, as established by the characteristic dark-on-light painted ware, centres on the north-east Peloponnese, although there are sufficient finds in the centre and west to establish its presence in those regions (Asea, Malthi, Pelikata, Teichos Dhymaion). In Phokis and Boeotia, the light-on-dark fabric predominates, but the two distributions interpenetrate. There are finds also in Euboia (for instance at Lefkandi II) but surprisingly few in Attica. The distributions have been compiled and discussed by French (1968, fig. 78).

The considerable elements of continuity between the Tiryns culture and the Middle Helladic culture, which Howell (1970) would prefer to call the Minyan culture, leads him to regard them as successive stages in a single cultural development. He would thus term the Tiryns culture (i.e. ‘Early Helladic III’) the proto-Minyan phase of the Minyan culture.

Recent finds at Lefkandi and other sites in Euboia suggest that the Tiryns culture (‘Early Helladic III’) was not the only cultural group in south Greece to follow the Korakou culture.

The Lefkandi finds showed that the site was first inhabited towards the end of the early bronze age. The Phase I finds there contain a significant proportion of wheel-made plates (Popham and Sackett 1968, fig. 7, 1 and 2), ouzo cups, in shape like those of the Tiryns culture at Lerna (ibid., fig. 7.5), one-handled cups continuing the Korakou culture tradition, and a two-handled cup. It is clear that these finds are distinct from, and later than, the Korakou culture (in fact a couple of sherds possibly of Urfirnis ware were found), but despite some resemblances with Lerna IV, they cannot be assigned to the Tiryns culture. It is not until Phase II at Lefkandi that the Tiryns culture painted ware and the early Minyan ware (or ‘proto-Minyan’) is seen. Lefkandi II can be equated with the developed stages of the Tiryns culture, as seen at Lerna IV. Lefkandi I may well belong chronologically between the period of Lerna III and Lerna IV.

Certain other finds in Euboia suggest that some of the sites without Tiryns culture finds were not necessarily uninhabited at the time of its floruit in the Argolid. The graves of Group III at Manika in Euboia (Papavasileiou 1910), in addition to their many Cycladic affinities (discussed in Appendix 2 below) have certain specifically north-west Anatolian similarities (fig. 7.3). The beaked jugs with a cut-away spout (Papavasileiou pl Z’, 2; pl. Θ’) in particular have good Troy IV parallels (Blegen et al. 1951, 9 and 110), and some of the incised ware (notably Papavasileiou 1910, pl. Z’, 1) has affinities with material from Iasos. Various finds, such as metal tweezers and one-handled cups, link the Manika tombs with the Korakou culture, but sauceboats and many other Korakou culture finds are missing. Yet the Korakou culture is well represented at the settlement of Manika (Theochares 1959a, 296, fig. 15), and a possible conclusion is that many of the Manika tomb finds are later than this date. Indeed Jacobsen has drawn attention to a wheel-made cup, found in Tomb V of Group III at Manika, which has Middle Helladic parallels (Papavasileiou 1910, pl. H, top row, left; cf. Sackett et al. 1967, 89). The obvious conclusion is that the Manika Group III graves lie in date between the Korakou culture and Middle Helladic, and perhaps contemporary with the Tiryns culture, a conclusion supported by the Troy IV parallels with the Tiryns culture at Lerna (Caskey 1960a, 297).

FIG. 7.3 Related pottery forms of Poliochni (1–2), Manika (3–4), and lasos. Not to scale.

The settlement at Manika has likewise yielded no Tiryns culture material, although there are plenty of finds of the Korakou culture. David French has convincingly shown (1966, 49; 1968, 62) that various finds from the settlement there, like those of Lefkandi I, are later than the Korakou culture and at least partly contemporary with the Tiryns culture: they have several Anatolian (Troy III–V) affinities.

At Aghia Irini on Kea a similar situation holds: the Korakou culture is well represented, yet the Tiryns culture is not, although finds like those of Lefkandi I (Caskey 1964b, 320 and pl. 49a), with Anatolian resemblances (French 1967b, 36), have been made.

The Lefkandi I assemblage is thus seen at other sites in Euboia, specifically Manika, and similar finds at Aghia Irini in Kea overlie the Korakou culture levels. Related finds from Syros have been termed the Kastri group. The Lefkandi I assemblage is as yet insufficiently investigated to be designated a ‘culture’ Doubtless further finds will be made in due course, notably in Euboia. The complex of finds is clearly in part of Anatolian inspiration.

The Middle Helladic culture, which succeeds the Early Helladic cultures, is well characterised by its pottery. The ceramic evolution has been studied in detail by Roger Howell (1970). The most characteristic features are the various classes of Minyan ware (grey Minyan, yellow Minyan, red Minyan, Argive Minyan), amongst which the pedestal bowls or goblets, and the bowls and jars with angular profiles are notable (Goldman 1931, pl. X, and pp. 136–44). Matt-painted ware is another striking innovation, with a wide range of form and decoration (Buck 1964; Goldman 1931, pls. XIII–XV), and incised and stamped wares persist. The identification of the Middle Helladic assemblage thus presents little problem, although Howell regards the Tiryns culture as actually a first phase, proto-Minyan, in the development of this Minyan culture.

The distinguishing ceramic characteristics of the Eutresis culture were defined above, and its distribution indicated by that of red-slipped ware bowls.

Well-stratified remains are known only from three sites at present, and our information about structures comes from two of these. The settlement at Lake Vouliagmeni at Perachora (Fossey 1969) was possibly surrounded by a circuit wall, which was later superseded by an earth bank with stone revetment walls on each side, and standing to a height of 2 m. This has so far been found at only one part of the site, so that its extent and purpose are uncertain. The buildings in the lower levels seem to have curvilinear walls.

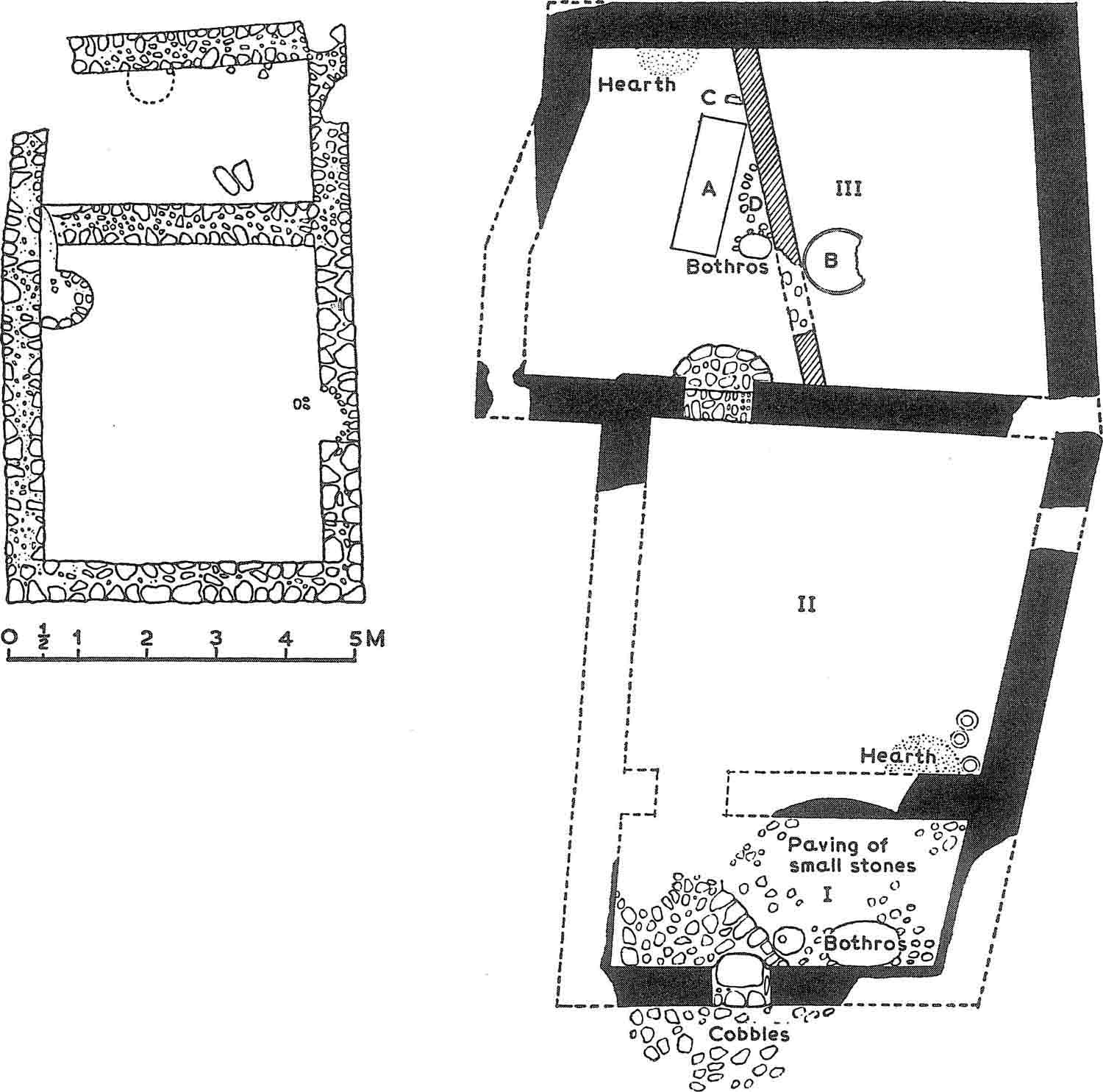

At Eutresis the excavations by Goldman revealed the stone foundations of a rectangular house measuring 7.3 × 4.3 m (fig. 7.4; Goldman 1931, fig. 8). This must be viewed as the south Greece counterpart of the Burnt House at Sitagroi in Macedonia (fig. 7.8). The difference in constructional techniques in the two regions is well brought out by the comparison. It should be noted, however, that the finds included a ‘sauceboat’, and the building is late in the Eutresis culture or may even belong to the Korakou culture. The Caskeys’ excavations at Eutresis produced similar although incomplete remains from Group V there (Caskey and Caskey 1960, fig. 9), with a series of well-laid pebble pavements in the courtyard. Part of a circular waif some 6 m in diameter, was also found enclosing a deep shaft, ‘the chasm’, whose purpose is unknown (ibid., 137, fig. 5). No burials are yet known from this culture.

The defining ceramic features of the culture have been discussed above. In addition to the Eutresis and Perachora finds, mention should be made of those from Palaia Kokkinia near Piraeus, where Eutresis culture pottery was found, including some spherical pyxides, and sherds with a decoration of stamped concentric circles (Theochares 1952a). Such sherds are regularly found as part of the Eutresis culture assemblage, and have been likened to the frying pans of the Keros-Syros culture. But both the form, as discussed in Appendix 2, and the decoration (Bossert 1960) distinguish the mainland sherds from the later Cycladic ones. The similarity is evident, but there is no need to think of these Helladic sherds as Cycladic imports.

FIG. 7.4 Houses of the Eutresis culture (left) and the Korakou culture (right) at Eutresis (after Goldman).

The further repertoire of finds of the culture is unimpressive: there are stone querns, flint and obsidian blades, bone tools, clay spools, whorls and other objects, including numerous loom weights at Perachora-Vouliagmeni. A single metal object, a flat chisel, has been found in a context probably of this period—from House I at Eutresis (Goldman 1931, fig. 286) (although the presence there of Korakou culture pottery was noted above). The material assemblage is thus rather undistinguished, lacking the variety seen in the next cultural phase.

The origins of the culture seem to lie in the preceding final neolithic. The pottery finds of Groups I and II at Eutresis may reasonably be seen as precursors of the Eutresis culture ceramics of Group III: this is the conclusion reached by French (1968, 62).

The Korakou culture ushers in a new era in the cultural development of mainland Greece. At this time the number of known settlements is greatly increased in both Attica and the Peloponnese, the essential homeland of the culture. The nature of the settlements changes markedly, and cemeteries are now widely found. Above all there is a marked increase in the connections and relations which the culture has with other areas in the Aegean, an increase related to, and enhanced by, the range of metal types now seen. This is the decisive phase for the emergence of civilisation in mainland Greece: until this time the culture was essentially neolithic—farming villages where subsistence was the main economic concern. From now on further occupations develop, and measurable wealth may be recognised. Not until the period of the Shaft Graves of Mycenae is a comparable increase in the wealth and variety of the material culture seen.

Here only a few of the main features of the settlements, cemeteries and material culture will be listed. The more significant developments are discussed again in later chapters.

The distribution of settlements of the Korakou culture is indicated approximately by the find spots of ‘sauceboats’ in mainland Greece (fig. 18.12). It is centred upon the Peioponnese, with 74 sites in French’s (1968) catalogue, and Attica, with 29 sites, as compared with 20 and 7 known sites respectively occupied in the time of the Eutresis culture. The main concentration of sites is still in the eastern Peloponnese, although the west is now more densely populated than previously.

This is the time when several fortified sites are seen (fig. 18.11 ). The semi-circular bastions at Lerna (pl. 20, 2) compare with those of Chalandriani in Syros. Askitario, Raphina and Manika were likewise fortified, and the walls of the Early Helladic settlement at the Apollo Temple in Aegina may date back to this period.

Two further developments are important: the first is the existence of large, and presumably public, buildings. The finest of these, the House of the Tiles at Lerna (fig. 7.5; pl. 20, 1) has been completely excavated: it was preceded there, still within the span of the Korakou culture, by a similar building at a different orientation. The House of the Tiles is rectangular in plan, measuring 25 m by 12m, and the building was divided into several rooms, with corridors and stairways leading to an upper storey. The walls were of square mud bricks, with stone socles, and the edifice was roofed with stone and terracotta tiles. The walls were plastered on the inside. Within this building was found an important deposit of clay sealings which had sealed jars and boxes.

Secondly, at Tiryns, the large but only partially excavated ‘Rundbau’, an impressive circular building, is of comparable size (fig. 7.5, lower). It too was roofed with terracotta tiles.

Some of the settlements at this period may reasonably be regarded as small towns. Part of the settlement at Aghios Kosmas is seen in fig. 6.4; it is of agglomerate plan, and very different from the single houses, standing rather widely spaced, such as are apparently still seen at Eutresis (Goldman 1931, fig. 13). At Zygouries, once again, we obtain a vivid impression of a compact settlement on the agglomerate plan. The mound measures 150 by 50 m, and in the areas tested was found to be occupied by a cluster of stone foundations (Blegen 1928, 5 and pls. I and II): ‘It is evident that the establishment or village as a whole consisted of numerous small dwellings set close together and separated by narrow crooked streets or alleys. One such street was traced for more than 10 metres....’ Blegen went on to describe the settlement as follows: ‘The dwelling houses at Zygouries are for the most part small and apparently of no standardised shape, though all are rectangular in design and regularly composed of two or more rooms. What seems to be a constant feature in almost all is the tendency to make the chief inner chamber roughly square in plan; indeed, this inner square room, sometimes small, sometimes relatively large, may be taken as one of the characteristic marks of these Early Helladic houses. In some cases there certainly was a fixed hearth in the centre of the room; in others no trace of any such arrangement could be recognised. The outside door in three cases, where satisfactory evidence of its position was preserved, led into the smaller of the two rooms forming the house, and in all three instances was placed on the long side of the building. The roof was undoubtedly flat; no trace of columns was found, and no column bases came to light, but it is possible that wooden supports were used where necessary. No rule of orientation was observed; since the houses appeared to have stood in groups or blocks formed by intersecting streets and lanes, these latter must have been the determining factor in the orientation of the buildings. There was some slight evidence for the use of party walls; but perhaps the two houses thus connected were not entirely independent dwellings. In a few instances it looks as if the houses faced an open court, which may have been surrounded by a wall.’ Large pithoi were found in several of the rooms, and the site gives a very clear impression of a fairly typical settlement of the time.

FIG. 7.5 Major buildings of the Korakou culture: the House of the Tiles at Lerna, and the ‘Rundbau’ at Tiryns.

A rather different picture is given by the finds at Orchomenos where the ‘Rundbauten’ probably belonged to this period (Bulk 1909, pl. IV). These are circular structures, whose stone foundations are preserved, of up to 8 m in diameter, the smallest having an interior diameter of 2.50 m. Their purpose is uncertain but they are so numerous that they should probably be regarded as dwellings.

Burial during neolithic times was generally intramural—that is to say in graves within the settlement, whether inside or outside the houses. The practice of intramural burial certainly continued during the Korakou culture: at Aghios Stephanos in Lakonia adults and children were buried in simple pit graves within the settlement, and this was a particularly common practice for child burials. Often the bones of a child were set inside a pithos (Frödin and Persson 1938, 42 and 212) following a custom seen already at Kephala in Kea in the final neolithic.

There are, however, three significant new forms of burial during this period. The first is that of the cist-grave cemetery, seen most clearly at Aghios Kosmas (fig. 19.10, 4; Mylonas 1959) where numerous cist graves, both of slabs and built of small stones, contained multiple burials. The similarity with the Cycladic cemeteries is an obvious one, and since these are already numerous in the preceding Grotta-Pelos period, a Cycladic origin seems likely. This is supported by its distribution, which is principally in Attica, although cist graves at Elaphonisos, off the southern tip of the Peloponnese, may be of this period also. An important cemetery has recently been discovered near Marathon.

Secondly there is the remarkable cemetery at Steno in the plain of Nidri in Levkas (fig. 19.11; Dörpfeld 1927). This was an extensive cemetery of 33 built circular platforms of stone, surmounted by tumuli, each containing one or more burials in pithoi or small cists. The dead were burned, although often incompletely, and many of the finds were damaged by fire: some of the goods were found in the traces of the pyres on the platforms rather than inside the pithoi or cists. The finds were extremely rich, including a series of metal weapons—daggers and spearheads mainly—closely similar to those of the Aegean itself (figs. 18.2 and 18.3). The ‘sauceboat’ finds and the other pottery lead one to place this cemetery in the Korakou culture. This has been questioned by some writers, but the series of graves in question, the ‘R graves’, unlike others on the island, contains nothing that has to be of later date. It is possible, however, that the Korakou culture persisted at Steno with little change until the beginning of the Middle Helladic period. Although nothing has been found elsewhere quite like these Levkas graves, the final neolithic graves at Kephala were likewise covered in several layers of stone, forming cairns of small size.

The third new burial form is the rock-cut tomb (fig. 7.6). Already as we have seen above, rock-cut chambers at the bottom of a shaft grave were dug in final neolithic times, in the Athenian Agora (Shear 1936). This may be regarded as the prototype for two similar tombs at the bottom of a shaft at Corinth (Heermance and Lord 1897). The graves contained either one or two skeletons each, and the jugs and ring-footed bowl place the finds within the Korakou culture. The cemetery at Zygouries may perhaps be classed with these, for the graves are dug in the rock, although not at great depth. Like all these cemeteries it is certainly extramural. Some of these graves contained several burials (Blegen 1928, 44)—Tomb VII at Zygouries had perhaps fourteen burials, and Tomb XX had fifteen. But these, like the Aghios Kosmas cist graves, should be regarded as instances of multiple burial, perhaps of a family, rather than of collective burial of a large group such as is seen in the Mesara tombs of Crete. The earlier of the rock-cut tombs at Manika may also be of this time.

FIG. 7.6 Aegean rock-cut tombs of the third millennium bc.

1. Manika in Euboia, tomb 1 of group 1 (Early Bronze 2 or 3);

2. Manika in Euboia, tomb 11 of group 1 (Early Bronze 2 or 3);

3 to 6. Phylakopi in Melos (Phylakopi I culture);

7. Corinth (Korakou culture);

8. Athens Agora (final neolithic).

The pottery of the culture has been briefly discussed. Mention should be made, however, of further shapes and features beside the ubiquitous Urfirnis and its Leitformen: the ‘sauceboat’, saucer and askos. In the fine wares the jug is also a common form, together with the narrow-necked jar. Dark-on-light painted ware, very similar in general appearance to that of the Keros-Syros culture is seen: the fabric is fine, and the decoration neat and rectilinear. Painted jugs occur, for instance, at Askitario (Theochares 1954a, fig. 6), and painted ‘sauceboats’—with which that of Spedos in Naxos (fig. 15.7, 5) may be compared—are seen at Aghios Kosmas, Eutresis, Lerna, Raphina and other sites.

Large pithoi are frequently found. A feature of special interest is the roll stamp with which these were decorated—there are good examples especially from Tiryns and Lerna (Wiencke 1970). At Lerna also a magnificent hearth was found, with impressed decoration (pl. 20, 3).

Vessels in stone are not common, but marble bowls, sometimes like those of the Cyclades, do occur especially in Attica and Euboia (e.g. Blegen 1928, pl. XXI, 7 and 8, and figs. 184 and 185; Mylonas 1959, figs. 164 and 165). A two-handled cup of grey marble, in form like the squat depas cup of Troy was found at Lerna (Caskey 1956, pl. 47, i and fig. 4). A feature of note on many sites is the small, beautifully worked pestle or grinder of fine stone (e.g. Blegen 1928, 196, fig. 186). Marble folded-arm figurines of Cycladic type occur at several sites (fig. 20.5). There are several marble figurines of forms related to those of the Cyclades at Aghios Kosmas (Mylonas 1959, fig. 163). In general, however, figurines are not common: the only distinctive mainland type is the narrow cone figurine, examples of which were found at Zygouries, Tiryns, and in Tiryns culture levels at Lerna (Blegen 1928, 187, fig. 177; Müller 1938, pl. XXV; Caskey 1956, pl. 47). There are other occurrences of less standardised form: a flat clay torso, neatly decorated in the Korakou culture painted style, was found at Lerna (Caskey 1955a, pl. 22, j and k). Clay animal figurines also occur at Corinth, Eutresis, Tiryns, Zygouries and other sites.

Stone beads and pendants of various forms occur. One of the most notable, of greenstone with relief spirals, from Asine, has resemblances with the carved steatite bowls of Early Minoan II Crete and the Keros-Syros culture (Frödin and Persson 1938, 241). Foot amulets were found at Aghios Kosmas and Zygouries (Mylonas 1959, fig. 116, 14; Blegen 1928, pl. XX, 3). But of especial importance are the sealstones, and the sealings. A sealstone from Aghios Kosmas (Mylonas 1959, fig. 166) is apparently of Minoan form, and may actually be an import from Crete, but this need not be the case for the two from Asine and Raphina (Frödin and Persson 1938, fig. 172, 1 and 3; Theochares 1953, fig. 15). Clay seals also occur—there is a fine example at Zygouries—and the style of most of these engraved seals is similar to that found on the numerous seal impressions from Lerna, and from Asine (fig. 7.7; Blegen 1928, pl. XXI, 4; Heath 1958; Frödin and Persson 1938, fig. 172).

Stone tools include the usual rubbers, grinders and polished flat axes, as well as numerous blades and scrapers of flint and obsidian. Hollow-based arrow heads of obsidian apparently make their appearance at this time, although they are not common. Two fine examples occur at Aghios Kosmas, and there is another from Zygouries (Mylonas 1959, fig. 166, 17 and 18; Blegen 1928, pl. XX, 23).

FIG. 7.7 Clay sealings (seal-impressions) from the House of the Tiles at Lerna (after Heath). Scale c.3:4.

The bone tools include a wide range of spatulae, scrapers, points and pins. Of particular note is a dagger pommel of bone from Zygouries (Blegen 1928, 191, fig. 180) and from this site and from the Tiryns culture at Lerna come distinctive and neat toggle pins (Blegen 1928, fig. 181, 10; Caskey 1956, pl. 47, a and f). Bone tubes, generally with incised decoration, which resemble those of the Keros-Syros culture at Chalandriani in Syros occur at Lerna, Manika and especially Levkas (Caskey 1954, 27; Papavasileiou 1910, 17; Dörpfeld 1927, Beilage 61, 4a and b).

The terracotta tools include the usual spindle whorls, and mention should be made of the clay anchors which are first seen in the Korakou culture, for example at Eutresis and Raphina (Goldman 1931, fig. 269; Theochares 1951, fig. 19), although they are more common in the succeeding phases.

A particularly important feature of the culture is the wide range of metal types which are found. The metallurgy of the period is discussed in chapter 16, but the major types may be indicated here. The hoards from Eutresis and Thebes indicate the range of tool types (Goldman 1931, fig. 287; Platon and Stassinopoulou-Touloupa 1964, 89 and fig. 5). Flat axes and chisels are the most common forms, but shaft hole axes, including axe-adzes certainly occur. The rich graves at Levkas document most of the other types which occur. The most important are the daggers, generally with a midrib and two or four rivets (fig. 18.3), and there are slotted spearheads. Simple flat, short daggers also occur. Awls and borers are, of course, common and there are in addition some knives.

The graves at Zygouries and especially Levkas document the range of more fancy items: spatulae, possibly for cosmetic purposes, tweezers (in silver at Manika), gold ear-rings and beads (which at Levkas are in a distinctive beaten gold technique), and bracelets and pendants of silver. Metal vessels are documented by the gold ‘sauceboat’ from Arkadia (pl. 19, 3) and perhaps the bowls in the Benaki Museum (Childe 1924, 163; Segall 1938, pls. 1–3).

This brief outline summarises only some of the principal features of the material finds of the Korakou culture. Its great significance in the development towards Aegean civilisation is emphasised again in Part II.

The origins of the culture have been disputed: it was once felt that the Korakou culture, perhaps like its predecessor the Eutresis culture, was the result of immigration to Greece by people from the east Aegean. But its resemblances with the cultures of west Anatolia are best explained by trade and contact. It is significant that at Eutresis, the only site where the transition from the Eutresis to the Korakou culture is well documented, it seems to be a gradual one.

The defining ceramic features of the Tiryns culture have been set out above. Known sites are much less numerous than for the Korakou culture, and indeed occur in about the same numbers as those of the Eutresis culture—but this may in part be due to the ease with which the typical Urfirnis ‘sauceboat’ sherds of the Korakou are recognised, even in weathered condition, on the surface of settlement sites.

Finds have been made in the Peloponnese, Attica, Euboia and central Greece, although there is some variation, since in central Greece the predominant decorative painted style is light-on-dark, and in the Peloponnese the converse is true. A complicating factor also is the presence in Euboia, and perhaps in Attica, of the Lefkandi I assemblage: it seems quite possible that these two distinct cultural groups coexisted in central and southern Greece for at least part of the Early Bronze 3 period. Well-stratified finds of this new assemblage come, however, only from small soundings at the type site, and although the Aghia Irini and Manika finds confirm its existence, our information about the Lefkandi I assemblage is at present restricted essentially to the pottery.

Many sites which in the older literature are termed ‘Early Helladic III’—such as Aghios Kosmas for instance—must now be regarded as belonging to the Korakou culture. Well-stratified deposits of the Tiryns culture are best seen at Lerna and Eutresis, and the finds from Tiryns and Aghia Marina are important. Our knowledge of the architecture comes effectively from Eutresis and Lerna. At Eutresis again, House H (Goldman 1931, 21, fig. 17) is altogether very similar to the Eutresis culture House I, already described, at the same site. It is in plan a narrow rectangle, nearly 6 m in width, with a large central room and a short room of the same width separated from it by a partition wall. There was a central column of mud brick (ibid., 25).

The houses of Lerna IV are of a different kind (Caskey 1966), and the settlement does not resemble the fortified one of Lerna III. Where the House of the Tiles had been, a low circular tumulus, 19 m in diameter, was raised and was left without buildings, enclosed by a ring of stone. The houses are now apsidal—like the Burnt House at Sitagroi (fig. 7.8), or indeed those of final neolithic Rachmani in Thessaly (Wace and Thompson 1912, fig. 17). This became the most frequent building form in Middle Helladic Greece. In the first phase of the Tiryns culture at Lerna these were timber frame houses, which are unusual in southern Greece. By the third phase the foundations were, as usual, of stone. There was no find of a large building at this period to compare with the House of the Tiles, or the Tiryns ‘Rundbau’.

So far there is little documentation for the burial practices of the time. Two child burials were found within the settlement at Lerna (Caskey 1955a, 37), and there may have been a cemetery at Thebes. But we know that the Lefkandi I assemblage was also flourishing at about this time, and many of the Manika rock-cut tombs must be contemporary with the Tiryns culture. It is not impossible that the Korakou culture continued into the Early Bronze 3 period at some sites, and with it its burial practices.

The material culture gives less evidence of variety than that of the preceding period. There are in general fewer rich finds. The elements of continuity are striking. At Lerna, for instance, there are cone figurines (Caskey 1956, pl. 47, j and k) which continue the type previously seen at Zygouries, and clay anchors (ibid., pl. 47), seen also at Berbati, which find precursors at Raphina and Eutresis.

Among new forms are the bone toggles seen at Lerna and Zygouries (ibid., pl 47, a and f; Blegen 1928, fig. 181, 10), where the context is, however, uncertain. Of great interest is the bossed bone plaque from Lerna IV, which has counterparts in the west Mediterranean (Evans 1956).

Fewer metal objects have been found, but this may simply reflect the small number of excavations with stratified deposits of the period—and may also be influenced by the late date of recognition of the culture. There is a dagger from Lerna, and a knife from Eutresis (Caskey 1955a, pl. 23, a; Goldman 1931, fig. 286, 7), and it should be noted that the R graves of Levkas may have continued in use well into the Early Bronze 3 period although the finds are still of the Korakou culture. The dagger from Aghia Marina is probably of this period (Sotiriades 1912, 276, fig. 15).

In general then the culture Is less strikingly wealthy than its predecessor, and certainly the rate of innovation and of change has decreased markedly. The origins of the Tiryns culture are not clear. At Lerna and many other sites, the Korakou culture occupation seems to have ended by fire. And on present evidence, even at Eutresis, where there is no destruction, the transition from Korakou to Tiryns culture was apparently a discontinuous one. If, however, this culture has no apparent clear antecedents in the area of its most marked development, neither has it any outside that area. But certainly the change from Korakou culture to Tiryns culture in south Greece seems more marked than any other subsequently seen in Greek prehistory, or any previously documented since the development of farming life.

The Thessalian early bronze age is less well understood than that of southern Greece, since there has not been the same intensive exploration, and much recent work has focused on the rich neolithic period of the area. The excavations of Milojčić at Argissa have given a division into three periods.

The final neolithic Larissa and Rachmani cultures, according to Milojčić’s observations (1959, 26), do not overlap with the Early Thessalian at all. In the earlier two periods of the early bronze age at Argissa, the material came from fortification trenches, while two building levels were observed in the third. These levels have been termed Early Thessalian I, II and III by Milojčić. But of course the relation of these periods to those in other areas of the Aegean is a separate problem.

The Early Thessalian I material, from the earlier fortifications trenches, contained no imported Urfirnis ware. The pottery was burnished undecorated ware, including bowls with incurved rims like those of Troy I. Lug and tunnel handles occur. Shallow cups with high handles are prominent (Milojčić 1959, fig. 21, 11–13), recalling those of Phase IV at Sitagroi, and of the Eutresis culture at the eponymous site. Of especial interest are the finds of corded ware, including the typical ‘Fischplatten’ so common in the Cernavoda-Ezero culture of Bulgaria (ibid., fig. 21.2).

French, however, prefers to regard the material from these levels (classified by Milojčić as Early Thessalian I) as of the Early Bronze 2 period. Thessalian Early Bronze I would then be defined by the same ceramic assemblage as characterises the Eutresis culture. French has collected much relevant material at no fewer than 45 Thessalian sites (French 1968, 68): it may be equated with what Milojčić terms Early Thessalian la, although this is not seen at Argissa.

In Early Thessalian II the striking cups with high-swung handles are absent. On the other hand there are high-handled deep cups, which Milojčić (1959, 27) links with the Baden culture, but which could relate equally to the high-handled cups of Troy IV and V (Form A33: Blegen et al, 1951, II, 2, fig. 187). Urfirnis ware is now common, and Milojčić equates this phase with the fully developed Korakou culture of Boeotia.

In the Early Thessalian III phase, bowls with ‘T’-shaped rims, already seen in Early Thessalian II, are numerous, They resemble somewhat the Troy shape A21 which makes its appearance in Troy II, the ‘T’ rim developing in Troy III. Two-handled cups with high handles make their first appearance (Milojčić 1959, fig. 23.7), resembling somewhat those found in the third settlement at Armenochori in Macedonia (Heurtley 1939, 193). Milojčić reports that Urfirnis ware is still common. On the other hand, the presence of clay anchors is without chronological significance.

Houses were built of clay or mud bricks, and no plans have been published for Argissa. Early Thessalian finds have come also from Tsani (Wace and Thompson 1912, figs. 86, c–g, and 88). At Zerelia three clay figurines may belong to this period. The painted ware of Lianochladhi III (ibid., figs. 125–30) has similarities both with that of the Tiryns culture and with Middle Helladic matt-painted ware. Since it occurred with Minyan ware goblets it should probably be attributed to the later phase.

Relatively little is thus known about this period in Thessaly: unfortunately the stratigraphic sequence for the end of the neolithic is uncertain on many sites, and there is sometimes doubt as to whether finds should be considered as neolithic or early bronze age.

The Thessalian finds present a number of chronological problems—for instance the occurrence of corded ware in Early Thessalian I levels, while it is attributed to the Tiryns culture at Eutresis. At present it is not easy to correlate the sequence with that of southern Greece. Re-excavation at a key site such as Lianochladhi or Orchomenos might be decisive here. But clearly the paucity of finds and the scarcity of metal are not coincidental.

Life in Thessaly during the early bronze age does not seem to have been markedly different from that of the late neolithic period.

The material from Macedonia is more abundant than is at present the case for Thessaly. In central Macedonia (Chalkidiki) the mound of Kritsana has yielded a stratigraphic sequence of six settlements, between which there is almost complete continuity in the ceramic finds (Heurtley 1939, 17).

In the earliest two levels some neolithic painted ware is still seen, and bowls with incurved rims, like those of Troy I, are common. Horizontal trumpet lugs are common in these levels, and clay anchors and hooks have been found. In levels III and IV these types are less conspicuous: globular bowls with narrow mouths are frequent (ibid., fig. 40, h and j). The potter’s wheel was already used in phase III, although for only a small proportion of the pottery (ibid., 80, n. 1). This may perhaps be contemporary with its first use in Troy in settlement IIb, and presumably earlier than its appearance in south Greece in the Lefkandi I assemblage and the succeeding Tiryns culture. Finally in phases V and VI bowls with flattened rims (like the ‘T’-rim of Early Thessalian II and III) are frequent, and loop handles are more numerous than tunnel lugs. Ledge lugs are also common. Jugs are found. Of great importance also is a single sherd, from level VI at Kritsana which is of Tiryns culture painted ware (Heurtley 1939, fig. 43). It seems clear, therefore, that Kritsana spans the period from Troy I to V, corresponding to the Eutresis culture/Tiryns culture time range. It does not follow, however, that the early bronze age occupation at Kritsana started early in the Troy I period.

Other sites in west and central Macedonia have a longer duration: the two-handled tankard of the third settlement at Armenochori is probably of middle bronze age date, and may relate to the Balkan series rather than to those of Troy.

Although the early bronze age finds of west and central Macedonia cannot yet effectively be sub-divided into phases, they give a clear picture of a fairly homogeneous assemblage. The stone tools include numerous stone shaft-hole axes and maces from various sites (Heurtley 1939, fig. 199), types not reliably dated to the early bronze age of south Greece, apart from an example at Korakou culture Lerna (Caskey 1956, 168). As in the south, hollow based arrowheads make their appearance at this time (Heurtley 1939, fig. 65, x–z). The clay objects include spindle whorls, and clay anchors and hooks. At Kritsana, clay anchors are found already in the first settlement, which may be their earliest appearance in the Aegean. The metal finds are limited to copper pins and a gold hair ring from Saratse (ibid., fig. 67, qq).

Recent excavations at Sitagroi in east Macedonia have given for the north Aegean a controlled stratigraphic sequence, with a quantitative study of pottery. As described in chapter 5, the ten metre stratigraphy has been divided into five phases, of which phase V may be sub-divided into two sub-phases. Phase IV may begin before the close of the final neolithic period, but certainly extends well into the span of the Eutresis culture of southern Greece, and hence into the Aegean Early Bronze I period.

The pottery of Sitagroi phase IV is dark burnished, and without painted decoration. There are apparently no figurines now, in marked contrast to the preceding phase. Shaft-hole axes of stone are not yet seen. Copper objects are still found, including a fish hook, but the forms are all rather simple. There is little in this assemblage to link it with the Troy I culture, but as already remarked, the shallow bowls with high handles constitute a parallel with Early Thessalian I and with the Eutresis culture.

FIG. 7.8 The Burnt House of phase Va at Sitagroi, East Macedonia. (a) and (b) indicate ovens, (c) is the main hearth (drawn by R. J. C. Wakeham).

The Burnt House at Sitagroi (fig. 7.8; Renfrew 1970a) is assigned to phase Va. Its well-preserved foundations give a clear picture of timber frame construction, with the walls chiefly of pisé mud. The northern end was semi-circular, so that the house is apsidal in plan, like House Q at Rachmani, which is apparently earlier in date. At this northern end was a utility room, divided by a partition from the rest of the house and containing storage bins, a bread oven, a second oven, and several querns and grindstones.

The house contained a series of pots, some of them decorated with incised decoration, resembling the Furchenstich decoration of central Europe. There are few resemblances with the Troy I culture, yet Sitagroi Va must be set contemporary in part with Troy I. Cord-impressed ware is first seen at Sitagroi in phase Va.

The uppermost levels at Sitagroi, phase Vb, contained the remains of a long house, some 18 m in length. The construction was again of pisé set on a timber frame. Numerous storage bins were found. The pottery now includes many bowls with horizontal tubular lug handles as well as one-handled cups, which are the Leitform of the culture. Jugs are scarcely found, however. The terracotta objects include clay anchors and hooks, like those of the Troy I culture and the Bulgarian early bronze age (Renfrew 1969b, 26). For the first time shaft-hole tools of stone are found, including a fine axe with the end in the form of a feline head. Some of the metal objects are now of bronze.

The finds show several resemblances with those of early bronze age Troy. A two-handled cup suggests that Sitagroi Vb extends beyond the span of the Troy I period, and the radiocarbon dates support this view, indicating that Sitagroi V may cover much of the early bronze age.

Unfortunately the occupation at Sitagroi does not extend beyond this point, so that whether or not the same culture persisted in this region, perhaps until the end of the early bronze age, is not clear. But certainly we see at Sitagroi few of the innovations in settlement plan, in organisation, and in craft technology, which are evident in southern Greece and in the Troad. In fact the early bronze age cultures of Macedonia, like those of Thessaly, show little clear advance on the preceding neolithic period. At Sitagroi the finds of phases IV and V are dull and unimpressive when set beside the variety seen in Stratum III. It seems that Thessaly and Macedonia hardly participated in those changes during the Aegean early bronze age which brought about the emergence of Aegean civilisation.