The basic division of the Early Cycladic finds into three cultural assemblages was established in chapter 9. Although there is only limited material from the Phylakopi I culture, principally since only a single cemetery is known, finds of the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros cultures are exceedingly abundant. In consequence, a definition is possible of groups of materials within these two cultural assemblages, where artefacts of specific type regularly occur in association. Both geographical and chronological factors, within the range of time and space of the culture itself, govern these associations. These groups may be regarded as sub-cultures, as recurrent assemblages of artefacts occurring always within the cultures already defined.

A treatment of these groups occurring within the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros cultures is given below, together with a description of the Attic-Cycladic Mischkultur. This further group, centred upon eastern Attica, displays elements of both the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros cultures.

In general in the Grotta-Pelos cemeteries marble objects and clay pots are seldom found in the same grave. Only the schematic figurines (fig. 19.4) are regularly found with pots, as in Grave 100 and especially Grave 103 at Pyrgos, in Grave 111 at Leivadhi and in Doumas’s cemetery at Akrotiri. They are in turn linked by associations with the marble rhyton (pl. 1, 4; Grave 117 at Krassades) and the footed kandila (pl. 1, 3; Grave 24 at Glypha). But the marble vessels are scarcely found with the pottery ones. That they belong broadly to the same culture is clear enough, and is at once obvious through a comparison of the kandila, the principal marble form (fig. 10.3, 4; pl. 1, 3), with the footed pottery jar (fig. 10.3, 2; pl. 3, 5), which is very common in the cemeteries. This distinction between graves with marble vessels and those without may not simply be a social phenomenon.

At the cemetery of Pelos in Melos, from which numerous pots are known (pl. 3), not a single object of marble was found. The lack of a source of marble in Melos might lead one to disregard this as a significant feature, but the museum in Melos has figurines of marble, including schematic forms, so that they are found elsewhere on the island. In addition at the important cemetery at Lakkoudhes in south-west Naxos, an island noted for its marble figurines, amongst many pots of Pelos type, no single object of marble was found. It would seem therefore that the feature has some other explanation than scarcity of marble.

The marble kandila is found chiefly in cemeteries such as Plastiras and Glypha in Paros, which have a rather varied repertoire, with both pots and marble vessels, although these are not found together in the same graves. A particular type not found in association with the pottery is the Plastiras figurine (fig. 19.5, 11; pl. 2, 2–3). Until recently it was known only from the publication of Tsountas (1898, pl. 10, 4) but there is an unpublished example in the Ashmolean Museum (AE 417), a specimen from Delos in Berlin (Majewski 1935, pl. XXIII), and others of the type are known (Renfrew 1969a, 6). The discovery by Doumas of three figurines of this type in Grave 9 at Plastiras, together with two kandiles, and of another such figurine in Grave 7, transforms the picture. It is clear that we have an important type and the indications are that it may be relatively late.

The evidence for two clumps of material leads one to suggest a Lakkoudhes group and a Plastiras group of the Grotta-Pelos culture. The Lakkoudhes group is characterised by the severe regularity of the incised decoration of the pots—the herring-bone motifs on the pyxides are nearly always horizontal—and by the absence of marble vessels. The Plastiras group is composed chiefly of marble objects, since pots are rarely found. The most frequent of these is the kandila, but the flat based rhyton is not rare (fig. 10.5 gives the distribution) and the most striking form is the Plastiras figurine. It seems most probable that the Plastiras group is later than the Lakkoudhes group. The schematic figurines are sometimes found both with pots of the Lakkoudhes group, which certainly long continued in use, and with the marble vessels of the Plastiras group. They may be considered a chronologically intermediate form.

The term Kampos group was first used by Fischer-Bossert (1960, 4) for finds from the eponymous cemetery in Paros, known also as Aghios Nikolaos. The term Kampos type will here be used for the ‘frying pan’ found there (Varoucha 1925, 107, fig. 9) and others that are known from Naxos (Kontoleon 1949, 120, fig. 10) and perhaps Syros (Zervos 1957, pls. 224–25). The defining features of this type are a straight side, as opposed to the incurving one of the Syros type, always decorated with an incised line or lines forming running spirals; the handle is rectangular and has a crossbar, and the main surface is never decorated with stamped devices, but always with an incised design of running spirals found usually in a triple line; they run in a circle round a central star motif (pl. 4, 1). It has been possible to study nine fragments of this form from Grotta in Naxos, and in addition to those quoted above, there are two from Naxos now in the National Museum in Athens (6140 Γ and Δ) as well as a fragment from Kato Akrotiri in Amorgos (Tsountas 1898, pl. 9, 16). The example from Louros (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pl. 60) is rather similar. Outside the Cyclades only a single example is known, from Manika in Euboia (pl. 4, 12) although the type does seem to have been imitated in a further example from the tombs on the same site (Papavasileiou 1910, fig. 14) and another from Markopoulos (Theochares 1955a, pl. 1).

The Syros ‘frying pan’, on the other hand, has an undecorated incurved side and a two-prong handle (pl. 7, 1). It is usually decorated with a network of stamped concentric circles or spirals, which in Syros are often complemented with incised boats (pl 29, 1; fig. 17.6). The design is surrounded by Kerbschnitt zig-zag. Although at least four examples from Syros lack the stamped decoration (Athens NM 5012, 5077, 5153, 5164) they are linked by the other features to this group. Outside Syros it is represented by an example in Mykonos, a sherd from Grotta, and a large fragment in Apeiranthos. From the mainland it is known only by an example from Raphina (Theochares 1951, 88, fig. 14), appropriately from a Korakou culture context.

It is clear that the Kampos type belongs firmly with the Grotta-Pelos culture, while the later Syros type is an integral part of the Keros-Syros culture. Neither is much found on the mainland, where a different type, itself scarcely seen in the Cyclades, was in use (see below). It seems difficult to determine the use of these remarkable vessels, whether trays or even mirrors. Specimens will have to be found in associations more carefully recorded than hitherto, before any firm conclusion can be drawn.

Another form occurring in the Kampos cemetery is the incised bottle (Varoucha 1925, fig. 7) which is known from several other islands, but never in such good associations (pl. 5, 3–5). A suggestion that these finds at Kampos may lie rather late in the time span of the Grotta-Pelos culture is afforded by the marble-footed cup (Varoucha 1925, fig. 6), of a form more often seen in the Keros-Syros culture.

The exceptionally rich grave at Louros in Naxos shows certain similarities with the Kampos finds (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pls. 66–67). Along with two spherical pyxides of the Grotta-Pelos culture were found a ‘frying pan’ (which may in fact be a pyxis lid) with a flowing decoration of incised spirals. While not identical to those of Kampos type it is similar. Incised spiral decoration is seen again on four tiny jars (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pl. 66). The Louros grave is unusual in containing metal objects—a necklace of silver beads, and three quadrangular awls like those found at Chalandriani in Syros. Finally it contained six arm-stump figurines of marble (pl. 2, 1; Papathanasopoulos 1962, pl. 70) of a form which has been designated the Louros type (Renfrew 1969a, 6). Other examples of this figurine form are known from the Cyclades, but not from well-stratified contexts.

This curious assemblage certainly does not belong to the Keros-Syros culture, despite the copper awls. And it would seem simplest to place it in the Grotta-Pelos culture, alongside the Kampos group.

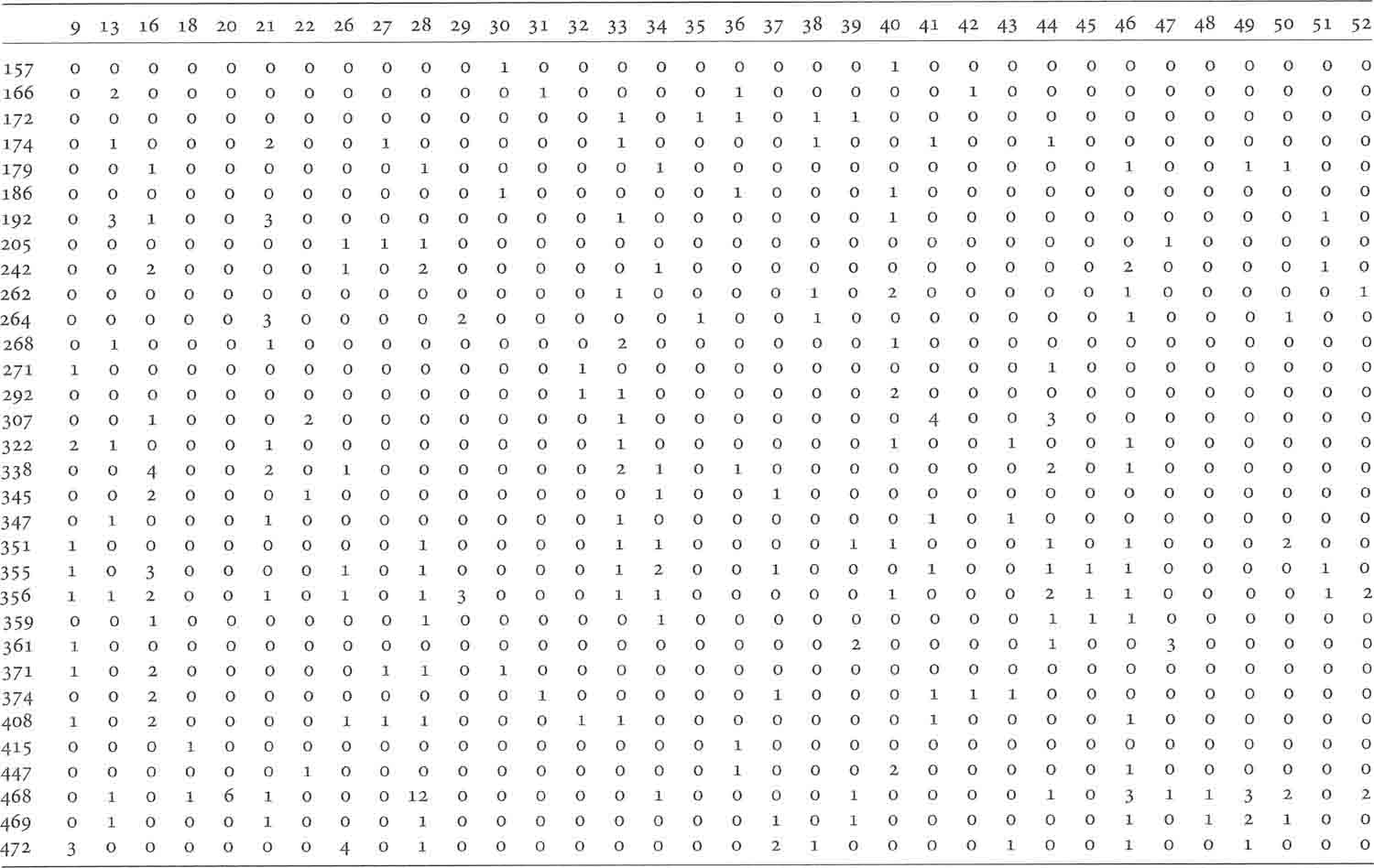

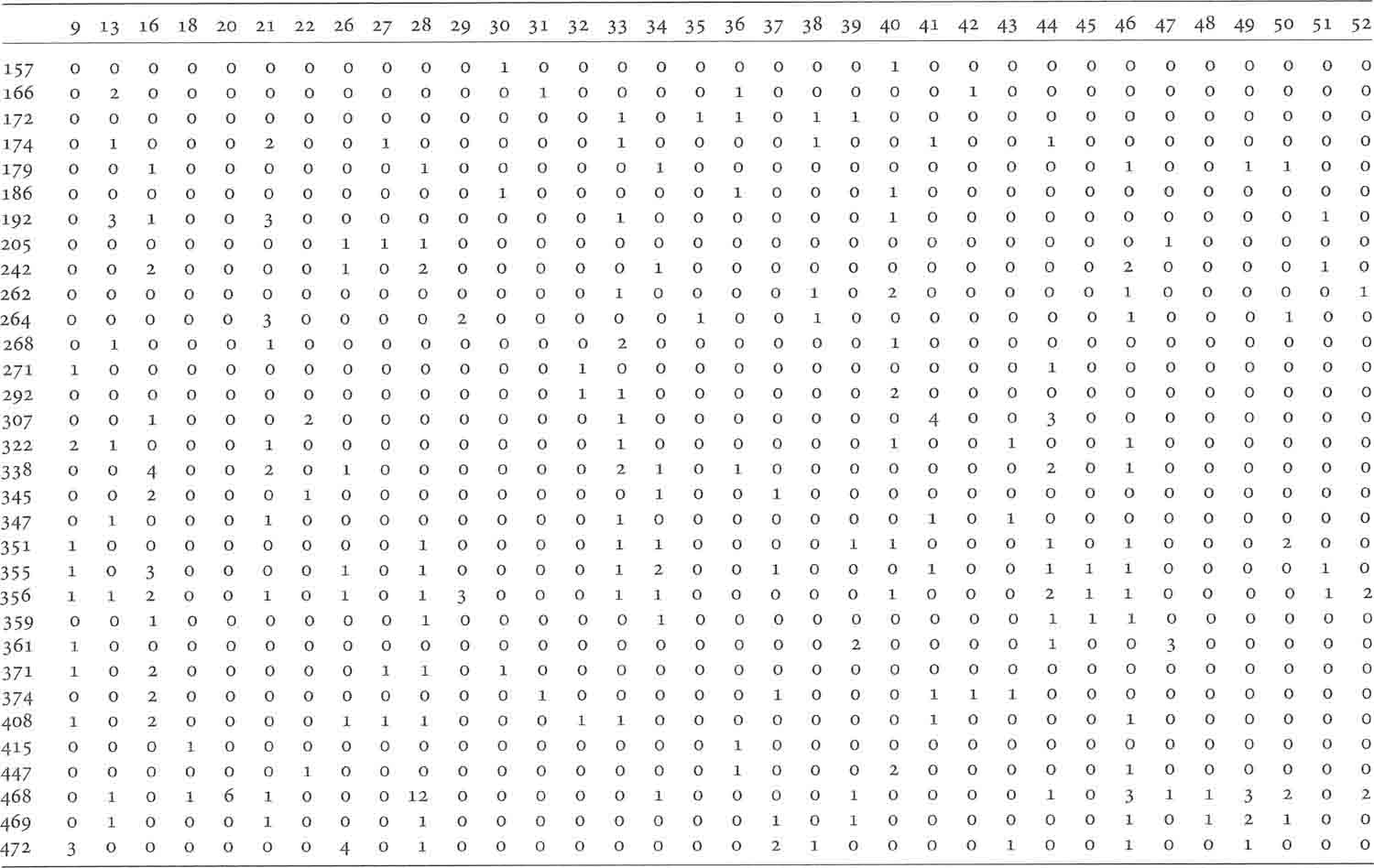

The great cemetery at Chalandriani in Syros was excavated by Tsountas in 1898. In it he found nearly 500 graves, usually constructed of small stones, and each containing a single burial. The graves did not always contain grave goods, but some were extremely rich, and the associations are of great value for proving the contemporaneity of types. For since all the objects in a given grave are the product of a single inhumation, the conclusion seems warranted that associated forms are contemporary. The associations at Syros which can be gleaned from the publication of Tsountas are summarised in table App. 2.1. The painted wares are seen in pl. 7, 2–5 and fig. 11.1, 9; the stamped forms in pls. 7, 1 and 8, 10–11 and in fig. 11.1, 1 and 10. The spherical pyxis is shown in fig. 11.1, 3 and the ‘sauceboat’ in pl. 19, 4. The various marble vessels are illustrated in pl. 6 and fig. 11.1, 4 to 8.

One of the first points to strike the eye is the wealth of metal objects (fig. 11.3): 10 tweezers, 16 spatulae and so forth, in a total of only 32 graves listed by Tsountas (although admittedly these are the richest which he excavated). Another feature is the presence of just a few extremely rich graves such as 468 and 469 which unite, in a single burial, many of the principal Syros types. The graves were selected by Tsountas for publication, and the 16 ‘frying pans’, for example, are about half the total found in the entire cemetery. The 6 little conical cups, on the other hand, can represent only about one-twentieth of the total found (cf. pp. 374–75).

These few graves, then, give only a part of the information which the cemetery finds originally contained. In order to test for inherent structure within the grave associations—whether in terms of seriation or of clustering—a similarity matrix was constructed for the 32 graves. As in the analogous case for the Cycladic cemeteries, described in chapter 9, two procedures were adopted.

In the first, punched cards were used to construct the similarity matrix, the similarity between the graves being defined as the number of types common to both graves divided by the total number of types in the poorer of the two graves in question. Close-proximity analysis was then used to look for some patterning in the relations between the graves.

In the second, the Kuzara, Mead and Dixon programme was employed in the manner described in chapter 9 for the Cycladic cemeteries. It produced first a percentile incidence matrix, and then a similarity matrix. This matrix was seriated using their programme, and subjected to close-proximity analysis.

No structure or patterning in the material emerged. There was some clustering around the richer graves, but no overall linear or cluster pattern was obtained. It was concluded that the graves cannot meaningfully be subdivided into groups.

A few minutes’ study of Table App. 2.1 shows that all the types are related, by several associations, to the main body of material. The list of types is given in Appendix 3. In particular, the painted wares (Types 30–32) are securely associated in numerous Instances with the stamped and incised ‘frying pans’ (Type 33) or the footed jars (Type 37, 38 unstamped). No distinction of any kind can be made there, and the painted wares must surely be contemporary with the stamp-decorated forms.

The four folded-arm figurines (Type 22) are similarly related to the ‘frying pans’, and in one instance to a metal spatula (Type 46). As stressed above, the schematic figurines (Type 18) do not closely resemble those of the Grotta-Pelos culture, and the two examples recorded are securely associated with a footed jar and a cylindrical pyxis respectively. The rich metal finds, and the bone tubes (Type 44) and bird-headed pins (Type 45) are likewise related to the remainder of the material by numerous associations.

Perhaps of some chronological significance in the placing of the Syros graves in relation to other cultures are the spouted bowls of marble (Type 43), the marble footed cups (Type 41) and the bronze pins (Type 47 and 48). All belong firmly with this assemblage. Nor is the obsidian isolated, and its use clearly continues after the Introduction of metal.

Certain forms from Chalandriani are not represented in the 32 graves chosen by Tsountas for detailed publication. The only painted form without published associations at Syros is the attractive footed cup (pl. 7, 4; Tsountas 1899, pl. 8, 4) found in Grave 407. A fragment of this type was found in the twelfth half-metre of deposit in Square J 1 at Phylakopi and the form is thus of some chronological importance. It has been compared with cups of metal from Troy II (Schmidt 1902, 5865, without handle). Another important shape for which we have no associations in Syros is the elegant one-handled cup (fig. 20.4, 1; Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 9 and 11), of which one example comes from Grave 392. Fortunately, however, four of these were found together by Tsountas with one of the painted footed form in Grave 142 in Siphnos. With these were a marble bowl (Type 16) and metal tweezers (Type 26), so that they can well be considered a part of the complex of associations of the culture.

TABLE APP.2.1 Incidence matrix for the recorded graves of the Chalandriani cemetery in Syros. Grave numbers indicated on the left. The number in the matrix indicates the number of occurrences of the type in question in the specified grave. Types as listed for Table App. 3.1.

Another important form not well associated is the ‘sauceboat’. Although several fine examples were found by Tsountas (pl. 19, 4; Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 8), the two from Graves 347 and 361, whose associations are given in Table App. 2.1, are flat based and really little more than spouted bowls. So to tie this form in with the complex it is necessary to look to Dhaskalio in Keros or to Spedos in Naxos. The other prominently Early Helladic type (Korakou culture) is the ring-footed saucer, an example of which (fig. 11.1, 2) was found in Grave 374, again in association with other types of the complex.

It is worth specifying also two types not listed in Table App. 2.1 which are of interest because of possible Cretan connections. The little Incised steatite vessel (Tsountas 1899, pl. 2) was found in Grave 408 along with a painted high necked jug; and the stamp decorated cylindrical pyxis (Tsountas 1899, pl. 8, 12) is from Grave 264, together with various metal objects and a typical footed cup. In Crete these would find the closest parallels in the Early Minoan II period.

Closer examination of the Syros types, in particular of the decoration of the ‘frying pans’ and of the footed vessels, might possibly allow of a subdivision into phases of the period represented by these very numerous burials, if further associations were available. But Dr Fischer-Bossert has told me that she can see no evidence which would lead to a subgrouping of the material in this way, and it seems that the Syros graves may best be regarded as a unity.

It is extremely difficult to judge how long these cemeteries were in use. Given a wealthy village settlement of 200 people, where it was the custom to provide each deceased adult with decent burial in his own specially constructed grave, a space of 150 years would be sufficient to account for 500 tombs. This period, however, is clearly a minimum, and could be multiplied several times, with only the homogeneity of the material counselling caution.

In 1963 and again in 1970, when I visited the recently discovered cemetery of Dhaskalio in Keros, the slopes of the hill were littered with a great wealth of sherds. In a couple of hours it was possible to pick up numerous fragments of ‘sauceboats’, some of them painted, abundant ware of Keros-Syros or Korakou culture type as well as a great variety of obviously local products such as the rather coarse footed jar (cf. Papathanasopoulos 1962, pl. 50, b–c), the domestic counterpart of the footed jars in the Syros graves. Amongst the marble fragments were several pieces of folded-arm figurines and dozens of bowl fragments, mostly with rolled rims. This interesting form is the counterpart in marble of the Grotta-Pelos domestic ware. It is found sometimes in the later graves of that culture, and is one of the elements of continuity between the two cultures. There were several fragments of another marble form, the cylindrical pyxis with horizontal grooves. Examples of this type, reputedly from Syros, are in the British Museum (pl. 6, 3) and the British School (pl. 6, 4) but this is the first time it has been recovered in the Cyclades in circumstances that can be documented. All these are products of the Keros-Syros culture, and nothing was found that would belong to the Grotta-Pelos culture. However a few spouts, apparently of duck vases were found, and this single feature may indicate some overlap in time with the Phylakopi I period.

In autumn 1963 the cemetery was excavated by Doumas. Amongst the rich finds, which he has kindly permitted me to examine and draw, are stamped and incised sherds of a high footed vessel (Type 37; cf. pl. 8, 10), but no ‘frying pan’ fragments at all have been recovered. The painted repertoire includes spherical pyxides, high-necked jugs and ‘sauceboats’ with decoration in thick lines running transversely across the spout comparable to fragments found at Lerna III and Poliochni III. Other decorated fragments resemble the Spedos and Raphina painted ‘sauceboats’.

The range in form of the stone vessels from Dhaskalio is truly extraordinary: it goes far beyond the usual Syros repertoire of concave-sided conical cups, often on feet, four-eared dishes and small spouted bowls. There are indeed fragments of several other shapes not recognised elsewhere in the Cyclades. Most striking of all are several fragments of pyxides, chiefly in a fine grey marble, with designs of interlocking spirals carved in relief. This at once calls to mind the similar vessels from Naxos (NM 5358; Zervos 1957, pl. 30), Melos (pl. 15, 1; Zervos 1957, pl. 28) and Amorgos (Dümmler 1886, pl. 1, 4). Both the pyxis from Maronia in Crete and the Asine pendant (Frödin and Persson 1938, 239 and fig. 173) show similar relief spirals, and although they may well be of local manufacture, they probably fall within the chronological span of the Keros-Syros culture.

The south of Naxos is another region particularly rich at this time. The Spedos cemetery has fortunately been recorded for us, and corroborates and extends the impression given by the Chalandriani graves. Grave 10 (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pls. 46–50) is particularly rich, with two folded-arm figurines, a marble spouted bowl, a painted sauceboat’ and two painted beaked jugs, as well as a curious painted triple vessel and a strange marble form, both without known parallel (fig. 15.7).

These painted jugs and ‘sauceboat’ offer a particularly close comparison with objects from the Korakou culture of the mainland, especially such Attic finds as the ‘sauceboat’ of Raphina (Theochares 1951, figs. 5–7 and 9) and the painted jugs of Askitario (Theochares 1954a, 67, fig. 16) and also Asine (Frödin and Persson 1938, 229, fig. 167.21). Painted cylindrical pyxides like those of Dhaskalio and Syros (Tsountas 1899, pl. 5, 7 and 8) are likewise found at Raphina (Theochares 1951, 84, fig, 8).

There is also a footed and closed-spouted bowl in Grave 10 at Spedos, which is not unlike the ‘sauceboat’ in shape. Other unusual ‘sauceboat’ variants are known in the Cyclades, and one wonders sometimes if they are not as much at home there as on the mainland. The other Spedos finds conform to the Syros range and include a bone tube and three schematic figurines of Syros type. Only the presence of a kandila in Grave 12, a Grotta-Pelos form already discussed, is rather surprising.

Other Keros-Syros finds from this area of Naxos but without exact provenance are the ‘sauceboat’ (fig. 20.4, 5), a painted pyxis lid, a Syros-like footed jar from Kastraki and part of a ‘frying pan’ (Renfrew 1965, pl. 43, 1). The last of these is one of the few examples found outside Syros itself of a ‘frying pan’ of Syros type, with elaborate decoration of interlocking stamped spirals. Also from Naxos are the attractive finds from near Aghioi Anargyroi, some of which could be classed in the Amorgos group.

Siphnos also has graves of the Keros-Syros culture (Tsountas 1899, 74) as does Mykonos (Belmont and Renfrew 1964, 397). The rigorous geographical division of the Cyclades into North and South, with the Syros group supposedly restricted to the north, is further belied by the discovery of a jar, clearly of Keros-Syros inspiration, in Melos (pl 8, 9).

In 1965 it was possible to draw attention to a number of black burnished vases (Renfrew 1965, 100), mostly excavated by Stephanos at Chalandriani, which are not well tied in with the 32 rich graves at that site, documented in Table App. 2.1. They include a high-necked jug of ovoid form with incised grooves on the sides (pl 9, 1; Athens NM 4998; Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 2 from grave 169: Zervos 1957, fig. 195; cf. also Zervos 1957, fig. 196 with elongated oval shape), spouted pots rather resembling Early Minoan II ‘teapots’ (pl. 9, 2; Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 14 from grave 392: Zervos 1957, fig. 194; also Athens NM 6140.2 and 3: Zervos 1957, figs. 192–93), a spherical pyxis with incisions (pl. 9, 3; Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 20, from grave 432) and a very lustrous black, handled cup (pl. 9, 4; Athens NM 5026, Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 5: Zervos 1957, fig. 184).

The spouted pot occurs with a one-handled cup in Grave 392 (Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 7 and 14), and examples of this form have been found also on Naxos. The incised pyxis is found both on the Kastri fort and at the Kynthos settlement on Delos.

The publication of the finds from Fischer-Bossert’s excavations at the hilltop fort Kastri, at Chalandriani, make it possible to enlarge the repertoire. There, together with the incised pyxis (fig. 11.2, 3 5 Bossert 1967, fig. 4.2), a series of two-handled depas cups is found, as well as steep-necked jugs, a possibly wheelmade baking plate, and little miniature duck vases (fig. 11.2, 1). Metal objects were also found.

This assemblage, found in the abandoned ruins of the fort, clearly belongs to the last period of occupation of the site. Although only the incised pyxis is seen both in the cemetery and at the Kastri stronghold, comparison with Lefkandi in Euboia and Aghia Irini in Kea allows us to recognise these forms as constituting a single group, which we shall term the Kastri group of the Keros-Syros culture. It clearly belongs to the later part of the duration of the culture, and external comparisons to be outlined below place it in the Aegean Early Bronze 3 period.

On the other hand, the continuity with the preceding phase should not be underestimated. The marble vessels at Kastri (Bossert 1967, fig. 5.3–6) are of the form seen in the cemeteries. And the one-handled cup occurs widely in the Aegean in Early Bronze 2 contexts, being first seen at Eutresis and Lebena in the Early Bronze 1 period. In Grave 142 at Akrotiraki in Siphnos, this form occurs with bronze tweezers and a cup painted in the Keros-Syros style (Type 30 of table App. 2.1). This specific shape cannot be accepted as belonging exclusively to this late Kastri group, although examples with the distinctive and very lustrous black burnish (pl. 9.4; Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 5: Zervos 1957, fig. 184) may be so restricted.

Recent finds at Aghia Irini in Kea offer striking points of comparison with this material. At Aghia Irini there is a settlement of the Korakou culture, and Caskey (1970) has recognised a specific group of early bronze age material there as belonging to a later phase, still within the span of the early bronze age. The material includes a depas cup, a one-handled cup in dark burnished fabric (like that described above) and a bowl of red fabric which Caskey likens to those of Troy. Howell (1970), as well as Caskey compares these finds, with their obvious Anatolian affinities, to those of the lowest levels at Lefkandi in Euboia, the Lefkandi I assemblage (cf. chapter 7). French (in Popham and Sackett 1968; French 1968) has indicated the Anatolian resemblances of the Lefkandi finds, which can be equated with the Early Bronze 3 period of the north-west Aegean. And the depas cups and jugs at Kastri likewise clearly resemble forms of Troy III and IV.

The depas cups of Kastri are of two forms. The first, from Tsountas’s excavations (Bossert 1967, fig. 4) is short and squat: the same form is seen in marble at Lerna (Caskey 1964b, fig. 4 and pl. 47, i). The second (fig. 11.2, 4) is tall and elegant and occurs frequently in the Second and Third Cities of Troy.

The jugs are of three forms, of which the first two (fig. 11.2, 6; Bossert 1967, fig. 3.1–2) may be compared with other Cycladic finds as well as with shapes of Troy II and III. The very tall-necked jug (fig. 11.2, 5), however, is an Anatolian form, seen also at Manika in Euboia (Papavasileiou 1910, pl. 9), which is best paralleled in Troy IV (fig. 8.3; Blegen et al. 1951, 110). The affinities of this material are further discussed in the excavator’s original publication (Bossert, 1967, 72–73).

The Kastri group of the Keros-Syros culture may thus be set in the Early Bronze 3 period.

And the very close similarities with the Trojan materials do suggest direct contact of some kind with the Troad. But the elements of continuity at Chalandriani should not, on the other hand, be overlooked.

Some of the graves of Amorgos and also Naxos, while containing various forms characteristic of the Keros-Syros culture, such as the folded-arm figurine, introduce others which have not been found in Syros itself. These forms, prominent among which are the triangular midrib dagger and attractive spoons, handles and beads of green stone, may be considered to define the Amorgos group of the Keros-Syros culture. The daggers and one or two ceramic associations suggest that it extends to the middle bronze age of Crete and of the mainland.

The Ashmolean Museum possesses a duck vase of Phylakopi I type (AE 265; pl. 12, 6) found in a cist grave in Amorgos together with a dagger. Bossert (1953) has published an important dateable grave group from Arkesine with several vases of Phylakopi type in the lower compartment, and an interesting slotted spearhead in the upper one. Elsewhere in the Cyclades, Keros-Syros finds do not occur in this way with those of the Phylakopi I culture, which are generally later.

There is also at this time a characteristic rough-surfaced slightly coarse buff-coloured ware, which occurs in rather baggy shapes (Tsountas 1898, pl. 9, 21 and probably 22). A common form in this buff ware is the open-mouthed jug, often with criss-cross incisions on the handle (cf. pl. 9, 6 and Ashmolean AE 261 from a cist grave in Amorgos). It is markedly less well made than is usual in the early bronze age. Another shape occurring frequently in the Amorgos group is the globular jug with a very short neck (Tsountas 1898, pl. 9, 26). This must be a rather late form, developing out of the earlier globular jugs like those of Spedos (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pls. 51, 58c, 61).

Another feature of the rich Amorgos group is the abundance of finds of silver: pins, bracelets and even a diadem (fig. 18.1). The particularly rich grave at Kapros (Renfrew 1967a; Dümmler 1886, pl. 1) contained silver beads, a silver bowl, decorated ‘ivory’ and a seal which Frankfort (1939, 232 and 301) relates to the Jemdet Nasr period. This dating has been contested by Kenna (personal communication), but the form is certainly a new one to the Cyclades. A date at the very end of the early bronze age about 2100 BC would seem more appropriate however. Similar cross-stamps are seen on several sherds from Syros and Mykonos, but I do not agree with Bossert (1960, 14) that they are of much chronological significance, for such designs are common enough on seals and sealings elsewhere in the Aegean, notably in Early and Middle Minoan Crete. Silver pins have been found near Aghioi Anargyroi and at Lionas in Naxos, and the little green spoon with silver mountings from the same grave at the former site emphasises its place in the Amorgos group.

The Amorgos group may be viewed as a natural development, chiefly in Amorgos and Naxos, taking place during the later part of the Keros-Syros culture. Clearly it persisted until the beginning of the middle bronze age, but the continuity of its evolution makes close dating difficult except in favourable cases. It is evident that while the Kastri group of the Keros-Syros culture was flourishing in the northern Cyclades, the Amorgos group was at its apogee in the east-central region: they are both products of divergent evolution (together with Anatolian contact in the case of the Kastri group) from a more uniform Keros-Syros culture base. And both overlap in date with the Phylakopi I culture of the southern Cyclades.

The affinities of some of the early bronze age finds of Attica and Euboia with those of the Cyclades have long been recognised. Childe (1957, 51) regarded the Manika tombs as an integral part of his Northern (or ‘Syros’) Cycladic group, and Mylonas has written of Aghios Kosmas as a Cycladic colony (1959, 162).

Before admitting the similarities which some of the finds from these sites show with Cycladic forms, especially with the Keros-Syros culture, it will be as well to stress the numerous differences which prevent our regarding them either as colonies or a straightforward member of the cultural group. At Manika indeed there are very few finds which can reasonably be regarded as Cycladic imports. Rock-cut tombs of this kind (fig. 7.6, 1–2; Papavasileiou 1910) are not known in the Cyclades, the incised pottery (ibid., pl. 7, 1, 4–6 and pl. 8, 6) is likewise unknown in the islands, although the Kastri finds, like those of Manika, find their closest parallels in Troy III-IV (cf. fig. 7.3). Even the folded-arm figurine (ibid., fig. 2) is a little unusual in appearance. These are not Cycladic exports therefore, and the repertoire of forms contains so many non-Cycladic shapes (even the ‘frying pans’ are different, being mostly undecorated) that the group cannot simply be termed Cycladic.

The same is broadly true for Aghios Kosmas. While some of the figurines could well be Cycladic (Mylonas 1959, fig. 163.2, 4–5) there is little else that has to be. The ‘frying pans’ are not of the Kampos or Syros types, and indeed constitute the best examples of a new class. It is noticeable too that there is at Aghios Kosmas a mixing of Grotta-Pelos forms (e.g. fig. 142.155; fig. 147.191) with others such as ‘sauceboats’ or the numerous one-handled cups which form part of the Keros-Syros assemblage. This mixing does not occur in the Cyclades. Moreover a colony might be expected to show far more direct imports, and the argument that it was a Cycladic trading station for the export of obsidian (Mylonas 1959, 163) is not supported by the view that Melian obsidian was never a Cycladic monopoly (Renfrew, Cann and Dixon 1965, 242).

Besides these two sites are several others in Attica and Euboia (fig. 11.5). Often they have cist graves with marble objects amongst the grave goods. Schachermeyr has spoken of the Helladic-Cycladic Mischkultur, and while one might hesitate to apply the term too widely, it seems very appropriate to this limited region—Attica and Euboia—where Cycladic finds are so numerous, yet always in a context that is at least as much Early Helladic as Early Cycladic. One imagines considerable Cycladic influence, perhaps through trade, which would account for the Cycladic forms and even burial customs amongst the local Helladic settlements.

Marble figurines of Cycladic type are known from Manika, Styra, Sounion, Piraeus, the Athenian Agora, Markopoulos and Brauron. Marble vessels have been found at Manika, Aghios Kosmas, Porto Raphti and Makronisi (Theochares 1955a). Cist graves are found at most of these sites. In general the finds seem to resemble the Keros-Syros forms rather than the Grotta-Pelos ones. The Pelos type pot in the Benaki Museum (No. 7685, Jacobsen 1969b) must surely be a Cycladic find; indeed it is almost identical in shape and decoration to one found by Bent in Antiparos (Zervos 1957, pl. 62). It seems then that the Cycladic influences which produced the Mischkultur were strongest in Keros-Syros times. That they persisted into the Early Bronze 3 period is suggested by the similarity between the Kastri group, the finds of Lefkandi I and of final early bronze age Aghia Irini. But at this time the origin of many forms is to be sought in west Anatolia rather than in the Cyclades.

It has often been supposed that the sherds decorated with stamped concentric circles, found widely in Early Helladic contexts, are of Cycladic origin. Relatively few of these are from ‘frying pans’—frequently the shape is a lid without a handle—and a more careful definition of the Cycladic type shows that the mainland ones fall in a distinct category.

In shape the mainland ‘frying pan’ is very like the Kampos type with its straight edges and cross-bar handle. The decoration, however, is very different and quite characteristic (fig. 11.6). The edges are always decorated with vertical incised lines or rather jabs (pl. 4, 11, 13 and 14). On the principal circular surface the same motif is seen towards the edge. Generally but not inevitably there is a single ring of stamped circles connected by incised straight lines, and the decorative arrangement has circular symmetry.

Many of the findspots of this type—including some lids—are shown in fig. 11.7. All the finds of ‘frying pans’ from Aghios Kosmas fall in this category (all probably of Korakou culture date), and so do those from Aegina (pl. 4, 14–15). Only a single such sherd is known from the Cyclades (pl. 4, 11) from Grotta in Naxos. Of great importance is the find of such a fragment at Palaia Kokkinia near Piraeus (Theochares 1951b, 111, fig. 26a) for the prehistoric remains at this site seem to belong exclusively to the Eutresis culture. It occurs too in a similar context at Eutresis (Caskey and Caskey 1960, pl. IV, 4, 14) and elsewhere, so that although it persists into the Korakou culture, it clearly originates in the preceding period.

The very scanty finds of the Cycladic ‘frying pans’ on the mainland were mentioned above, and to these must be added a stamped footed jar of Syros type found at Askitario (Theochares 1954a, 75, fig. 26). There are apparently no further finds of Cycladic stamp-decorated sherds on the mainland. Certainly there is a great quantity of stamped and incised pottery but it does not compare closely with Cycladic shapes. The same conclusion was reached by Bossert (1960) through a very detailed consideration of the stamped concentric circles themselves. Some other explanation is required than the straightforward import of pottery.

In order to amplify and corroborate the chronology for the Keros-Syros culture discussed in chapter 13, it is worth looking again at the two chief sites in the area. Aghios Kosmas with its ‘sauceboats’, askoi, ring-footed bowls and painted ware clearly belongs to the Korakou culture. Mylonas himself spoke of two phases, Early Helladic II and III (1959, 159) but there is none of the painted ware of the Tiryns culture there. This has led Caskey to deny that Aghios Kosmas lasted into the Early Helladic III period (1960a, 300). He is certainly correct m pointing out that the Tiryns culture is not seen at Aghios Kosmas, but whether this rules out contemporaneity with that culture is perhaps less certain.

One of the most noted features of Aghios Kosmas is the practice of cist burial, which is not widely seen on the mainland until Middle Helladic times, and Mylonas is surely right to see in this evidence of Cycladic inspiration. The numerous one-handled cups are common In the Cyclades, as are the little concave-sided pestles (Mylonas 1959, pl. 166, 1–7) which are often made of pretty stones, and are seen at such sites on the mainland as Zygouries (Blegen 1928, pl. XXII, 16–21) and also in Crete. The incised pyxis (Mylonas, pl. 164, 160), how-ever, might more easily be Cretan than Cycladic. Although metal is not common at Aghios Kosmas, the tweezers (op. cit., pl. 163, 13) form a nice link with Manika (Papavasileiou 1910, fig. 4), with Zygouries (Biegen 1928, 183), with Eutresis (Caskey and Caskey 1960, 151) and with Syros (Tsountas 1899, pl. 10, 40–42).

Of great Interest are the few finds which suggest Grotta-Pelos influence. It is very difficult to make deductions from figurines, however, unless the parallels are very close. While there is an arm-stump figurine which can safely be compared with the Louros type (Mylonas 1959, pl. 163, 3) the schematic figurine whose head shows facial features (ibid. pl. 163, 1) is not easy to parallel, for those from Drios, in the Paros Museum, similarly with facial features, are of a different shape. Perhaps the pots with vertical suspension lugs (ibid., p. 147, 191 and 201; pls. 142, 169 and 155) most resemble Grotta-Pelos examples, although there is no herringbone incision at Aghios Kosmas, and the ware is rather coarse. In general the Cycladic affinities of Aghios Kosmas relate to the Keros-Syros culture, and support an equation between this and the Korakou culture of the mainland.

There are several Interesting features at Manika which, unlike those of Aghios Kosmas, cannot be explained as a simple Mischung of Early Helladic and Early Cycladic. Blegen (Blegen et al. 1951, 9) has, however, remarked upon the Anatolian nature of the beaked jugs, three of which (Papavasileiou 1910, pl. 9, lower, 3, 3) he would relate to Troy IV.

The non-Cycladic, and indeed non-mainland look of the incised ware has already been indicated, and two pots from Manika are compared in fig. 7.3 with others from lasos (Levi 1963a, fig. 97.9 and 5) and Poliochni Yellow (unpublished). The double-line pendant triangle with pointillé filling seems a particularly Anatolian motif. Indeed the one-handled cups (Papavasileiou 1910, pl. 8, top) are just as much Anatolian as Cycladic. What is particularly noticeable about the cemetery is the scarcity of Helladic forms, although these are certainly found in the settlement (Theochares 1959a, 292 f.). Here one really seems justified in seeing very strong west Anatolian influence, and indeed import. The indications are that this would be of Anatolian Early Bronze 3 date (Troy IV) although there is at least one pot, with two handles (Papavasileiou 1910, pl. XI, centre, lower), which look as if it could be of middle bronze age date. In any case, to regard the cemetery as Cycladic is just not justified.

Other tombs, perhaps located elsewhere on the site, have been opened more recently, and the finds there include undoubted Cycladic marble vessels (Theochares 1959a, 305) and a bird-headed pin of bone (ibid., 279). These at least allow us to include Manika in this rather curious Mischkultur.

This view, formulated in 1965 (Renfrew 1965, 115), is greatly strengthened by the recognition of the Lefkandi I assemblage. As stated above, the Lefkandi I finds, those of the Manika tombs, the Kastri group in the Cyclades and the recent finds at Aghia Irini in Kea, can all be regarded as related, as showing west Anatolian influence, and in Aegean terms as of Early Bronze 3 date.