The third millennium was, in the eastern Aegean also, a time of rapid and remarkable change. From the beginning of its occupation Troy was a fortified proto-urban settlement, as soon became Thermi in Lesbos, Poliochni in Lemnos and Emborio in Chios. Metallurgy advanced rapidly, and the most impressive metal finds of the Aegean prior to those of the Shaft Graves of Mycenae are the magnificent treasures of Troy IIg.

So far very little is known of the prehistory of south-west Anatolia, along the Carian coast. But there have been abundant finds from north-west Anatolia and the offshore islands. They are sufficiently numerous to yield a vivid picture. Why sites are so very much rarer at this time further south remains to be established.

Coastal Anatolia was, of course, in contact with other regions of western Anatolia, and significant points of similarity are found at Kusura (Lamb 1936b), at Beycesultan (Lloyd and Mellaart 1962), and at Karataş-Semayük (Mellink 1965; 1967). Since these sites fall right outside the Aegean basin they are not considered here: a detailed consideration of the west Anatolian early bronze age has been given by French (1968). None the less the Aegean can only be meaningfully considered and understood with a concomitant awareness of developments in the rest of Anatolia.

The most important known site in the eastern Aegean is Troy itself. Fortunately Troy is also by far the most fully investigated, first by the pioneering work of Schliemann and Dörpfeld, and then the meticulous and amply documented study by Blegen and his colleagues. Troy was divided by Schliemann into successive settlements or ‘cities’, and this system was given definitive form by Dörpfeld (1902) who established a sequence of nine cities, of which VIIa is now considered by many to be the Homeric Troy. Cities I to V are dated to the early bronze age, and indeed the north-west Anatolian early bronze age is now essentially defined by reference to the material from Troy.

Blegen and his colleagues decided to retain the Dörpfeld sequence (Blegen 1961; Blegen, Caskey, Rawson and Sperling 1950; Blegen, Caskey and Rawson 1951). Their full description of the contents of the successive strata allows correlation with other sites in north-west Anatolia and on islands near the coast—principally Thermi in Lesbos and Poliochni in Lemnos.

In the first section here the basic pottery and other changes which define the successive phases are considered, allowing the contemporaneity of other north-west Anatolian sites to be established. Then in succeeding sections the picture is filled out by considering the other material of the culture in the Troad. Brief reference is made also to the finds at Emborio in Chios and the Heraion at Samos, which fall within the same culture area, as defined by French (1968). The ‘Yortan culture’ finds are from the inland region of Balikesir, and thus not strictly within the Aegean area. But Iasos, the only excavated site of this period in Caria, although it falls outside the north-west Anatolian culture province, is of considerable importance. In a later chapter the interrelations with other areas of the Aegean and the absolute chronology are considered.

At Troy itself the earliest settlement is of early bronze age date. Only at the nearby site of Kum Tepe can something be learnt of the origins of the early bronze age in this area. The long-awaited monograph on the excavations there has not yet been published, but thanks to the kindness of Mr Blegen and the Turkish authorities it has been possible to examine the pottery, as discussed in chapters 5 and 10.

The characteristic ware is dark and well burnished, with thin-walled open bowls (fig. 5.3, 2) and especially thicker-walled open bowls with rolled rims in the Kum Tepe period (fig. 5.3, 5–9; Koşay and Sperling 1936, type d), being largely displaced by inturnedrim bowls (fig. 5.3, 11; ibid., type b) in the Troy I period. At present little more can be said, and the distinction drawn between ‘Kum Tepe Ia’ and ‘Kum Tepe Ib’ has probably been exaggerated. ‘Kum Tepe Ia’ remains to be adequately defined, but French (1961, 102) has made an effective case for a pre-Troy I ceramic phase in the eastern Aegean, which is now generally designated Kum Tepe lb. Its distinguishing feature is the dark-burnished open bowl with rolled rim (fig. 5.3), often with a horizontal tunnel lug set below the rim. This distribution of these bowls is further discussed in chapter 10 (cf. fig. 10.6).

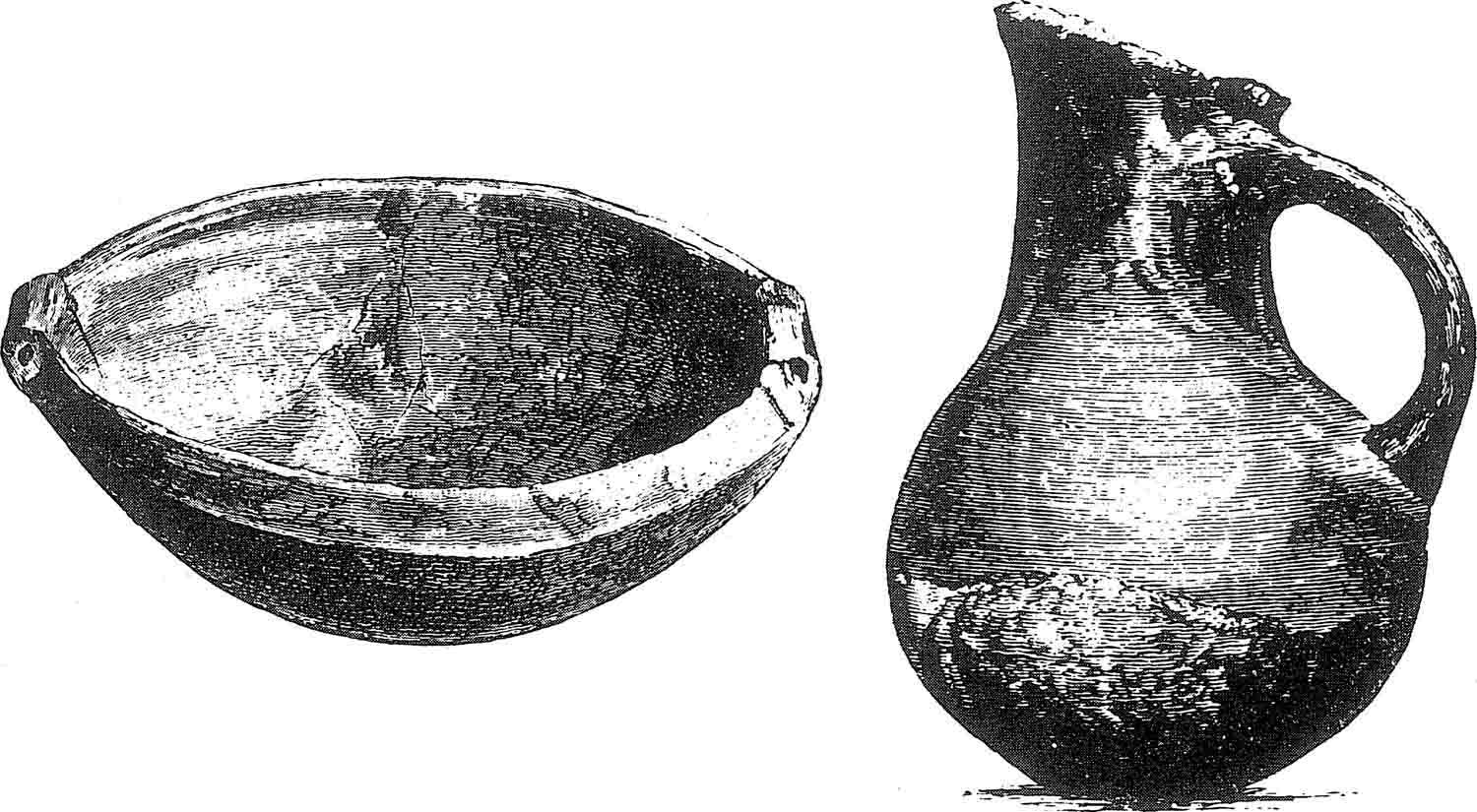

FIG. 8.1 Pottery of the Troy I culture (after Schliem arm). Diam. of bowl C. 30 cm.

In the Troy I period the pottery (fig. 8.1; Blegen 1961, 5; 1963, 52) remains dark monochrome, and the potter’s wheel is still unknown. Apart from the bowls there are spouted jugs, jugs with legs and various jar shapes. The first settlement has been divided into three sub-periods: in the first, bowls with thickened rims (Troy form A6) and angular bowls (Troy form A12) are common with footed bowls (Troy forms A7 and A13) and jugs with cut-away spouts (B16–19). In the late phase the pedestal bowls disappear, and a new curving-profile bowl becomes common (A16). Incised patterns are often seen, frequently on the inside rims of bowls. Just occasionally white painted decoration occurs. Copper awls, pins and a hook were found, and a clay mould for a midrib dagger (Blegen et al. 1950, 43).

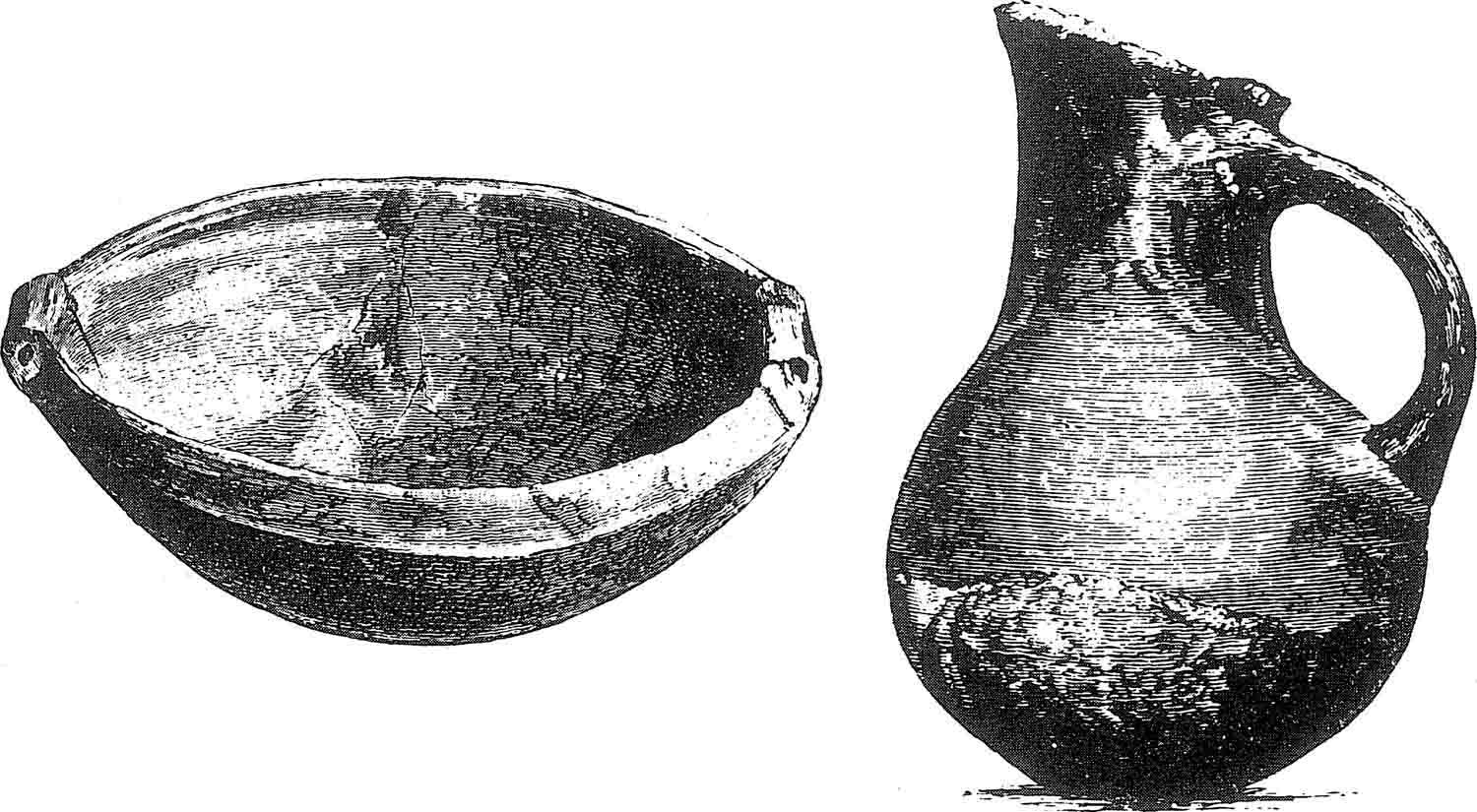

The pottery of Troy II (fig. 8.2) constitutes a separate assemblage, which shows a development through the seven successive strata. In the later phases the black and grey polished wares give ground to pottery in lighter colours: brown, tan and red. The potters wheel was invented (or introduced) in phase IIb. By phase lie numerous wheel-made flaring bowls (Troy form A2) are seen, and also heavy shallow dishes. At this time, the famous two-handled drinking cup, the depas amphikypellon (A45) makes its appearance, as also other one-handled (A39) and two-handled (A43) cups. Ovoid jugs and flasks are now seen (B7, B8), feeding bottles (B9) and globular or oval jars with a collar neck, sometimes with an applied human face on the side (C30) or on the lid (D13), which is surmounted by a knob. The curving-profile bowl (A16) remains common: sometimes there is now a horizontal loop handle at the rim (A11). Painted ware was not made locally, and decoration was limited to incisions, grooving or simple relief. The famous ‘Burnt City’, where Schliemann unearthed the splendid Trojan treasures, is now regarded as the last stratum of the Second City, Troy IIg. The very considerable range of metal types thus increases the range of diagnostic forms of the Troy II period.

The material of settlements III to V at Troy is generally grouped together, as representing the last phase there of the early bronze age. The third settlement of Troy is divided into four sub-phases. The pottery shows great continuity with the preceding period. The flaring bowl (A2) becomes thicker and deeper. The one-handled cups, depas cups, face pots and lids continue. The jugs with cylindrical neck and horizontal spout (B22) are now supplemented by beak-spouted jugs (B20) (fig. 8.3). A few terracotta animal figurines are also found.

The fourth settlement has five sub-phases. The pottery again shows little change. The use of straw tempering is now gradually adopted, and the potter’s wheel very freely used. One innovation is the jar with wing-like handles and applied plastic decoration (C29). A shorter version of the depas cup is now seen (A44), and the askos (D29), and bowls decorated outside or inside with a painted red cross make their appearance. The fifth settlement, the last of the Trojan early bronze age, comprised four strata. The pottery is again little changed. The red cross bowls are now common.

FIG. 8.2 Pottery from early bronze age Troy (after Schliemann). Ht C. 25 cm.

With Troy VI, the middle bronze age, there is a marked change in the cultural assemblage at Troy. This is best illustrated by the pottery, where a whole new repertoire of forms is seen. Grey ‘Minyan’ ware, like that of Middle Helladic Greece, is very common: the characteristic shapes include footed goblets, two-handled bowls and sharply carinated bowls. Handles in the form of animal heads are particularly characteristic of the period.

These indications, lacking as they are in very clear-cut criteria for the phases, do provide material for correlations with other west Anatolian sites. Among these is the Protesilaos mound (Karağactepe), where the rather confused stratigraphy produced material dating from the final neolithic to the Troy II period (Demangel 1926).

The important town at Thermi in Lesbos yielded five strata clearly of early bronze age date, above which were middle bronze age remains. Thermi I to V belong to the earlier part of the early bronze age (Lamb 1936a, 209). The pottery shapes in general resemble those of Troy I, and the depas cup is not seen, nor was the potter’s wheel known. The winged jar (Lamb 1936, 52; pl. XXXVI, 443) is consequently not to be confused with those of Troy IV. Cut-away jugs are seen, but not beak-spouted jugs.

Lamb believed that the brown wares which become dominant in Thermi Town IV were contemporary with those of the early Troy II period, and that Town V was abandoned before the end of the Troy II period. Blegen and his colleagues, however, regarded Thermi I-V as running contemporary to Troy I (Blegen et al. 1950, 40), and most later writers follow this view.

FIG. 8.3 Jug from Troy IV (after Schliemann). Ht 30 cm.

The site of Poliochni in Lemnos also spans the early bronze age. The sequence there has been divided into seven phases (Brea 1955,145; 1964,29). Period VII has Mycenaean material and is certainly much later than the early bronze age. The chronological equation with Troy is shown in table 8.1.

The correlation between Poliochni V (Yellow) and developed Troy II is immediate: the finds include abundant brown wares with depas cups (Brea 1955, pl. xv), flaring bowls, and knobbed lids. Brea suggests that Poliochni V may persist into the Troy III— IV period, and certainly the winged jar (Troy form C29) is seen.

Poliodini IV (Red) lacks the developed Troy II forms. But Brea (1955, 145) rightly suggested that it may persist into the Troy II period. Elegant cups (Troy form A39) are seen, the tripod bowls are common, and so are stone battle-axes. Poliochni II (Blue) and III (Green) can then be attributed to the early and middle phases of Troy I. Jugs are common, as are incurving bowls, tripod pots and especially a long series of footed bowls, for which there is no exact parallel at Troy. A little white-painted ware is seen, as at Troy. There are, however, features in the Blue phase already suggestive of Troy II, and Indeed the correspondence between the two sites is not complete. The preceding Black phase, phase I, probably antedates Troy I, although jugs are already seen (Brea 1964, pl. 1, f) and the bowl shapes do not compare well with those of Kum Tepe Ib.

TABLE 8.1 Comparison of the stratigraphic succession at Poliochni (where levels have colour designations as well as number) with the sequence of ‘cities’ at Troy.

| Poliochni | Troy | |

| VI | Brown | V |

| hiatus | ||

| V | Yellow | II, III-IV |

| IV | Red | Late I, Early II |

| III | Green | Mature I |

| II | Blue | Early I |

| I | Black | — |

This then is the reported pottery sequence of Poliochni. The published plans (ibid., plans 22–26), however, present certain difficulties. Different quarters In the same town are ascribed in their entirety to different phases, and the picture given indicates a curious shifting of location within the perimeter. Limited confidence therefore can be felt in dates assigned to objects simply on the basis of location. Closed finds, with good associations, constitute the only valid material.

The finds at Emborio in Chios (Hood 1965a) place it in the same cultural region as Troy and these other sites. The earlier phases were discussed in chapter 5. Strata V, IV and III have finds of the Troy I culture, although there are local variations, and the culture may persist in Chios after the time of its replacement at Troy by the Troy II culture. Emborio II is assignable to the culture of late Troy I or early II, and Emborio I to Troy II (Hood in lit 27 May 1969). But the finds of the Troy II culture at Emborio do not in fact seem identical to those at Troy: several elements of the Troy I culture persist.

The finds at Tigani on Samos are chiefly earlier than the early bronze age period, and have been mentioned in chapter 5. Those from the Heraion, on the other hand, are of early bronze age date, and place the site within the same culture region as Troy, although at its southernmost extension. The finds are not rich, but in giving an impression of the later material of the early bronze age well to the south of Troy have considerable significance. Milojčić (1961, 58) divides the finds into several groups, of which Heraion I to V are of early bronze age date. Heraion III has depas cups, and other forms suggesting a developed Troy II date. Phases I and II may likewise be assigned to Troy II. Heraion IV contains forms linking it with Troy IV (or V) beaked jugs, and short two-handled cups ( Milojčić 1961, pl. 16, 1-2; pl. 19, 7, etc.; pl. 15, 4 and 8; pl. 21, 5 and pl. 39, 22)—and there are several duck vases like those of the Cyclades (ibid., pl. 15, 2; pl. 18, 1-2; pl. 19, 8). Heraion V has bowls with outturned rims which can be compared with Troy V bowls of form A21 (ibid., pl. 39, 15 and pl. 44,13; Blegen et al. 1950, fig. 251). Although there are forms at the Heraion not seen at Troy, the general similarity in the finds is striking.

The picture we have of the Troy I culture can now be filled out somewhat with the aid of this chronological framework. We are fortunate in having the evidence of three major sites: Poliochni II–III, Thermi, and Troy itself. The finds from Emborio, when they are published, will extend this picture further.

The distribution of the culture has been given by French (1968, fig. 29, b.1), who lists 45 settlements on the coastal areas and off-shore islands of the west Anatolian coast between the Troad and Smyrna.

At Poliochni there are three strata immediately underlying those of the Troy I period, containing a village of oval huts (Brea 1964, figs. 25-28; 51-54). They yielded little except the heavy black burnished pottery already described. A few modest tools of bone and stone were found, but nothing in metal (ibid., 547, superseding Brea 1955,145). The earlier finds at Emborio have already been mentioned.

In Poliochni II (Blue) the settlement becomes larger. There is a defensive wall, and buildings now extend over some 200 m, the length of the settlement in later times. The plans for the successive periods at this site must, however, be used with caution. Thermi was likewise enclosed by a defensive wall, but not in towns I and II, which give the impression of a ‘peaceful agricultural community without fear of aggression’. The site was probably fortified in phase III, and certainly in phase IV it had a solid defensive wall. The excavated area was about 100 m in length, and the long narrow houses are clustered closely together. The plans of the successive settlements, which were meticulously un-ravelled during Miss Lamb’s excavations, and especially those of Thermi IV and V give a clear impression of proto-urban settlement (fig. 8.4).

Troy I was also fortified, and the enclosing walls—only 100 m in diameter—give it the impression of a citadel. The houses were apparently separate and free-standing: those at Thermi and Poliochni were more crowded. But the remains for this early period of Troy (Mellaart 1959a, 132) suffered badly during the first excavations at the site.

These four settlements, although small in size, differ markedly from the neolithic villages of the Aegean. With their stone-built fortifications and their controlled use of space within them, they may be regarded as ‘proto-urban’ in character. Thermi and Poliochni were indeed small towns: Troy a fortress.

FIG. 8.4 Plan of the early bronze age town at Thermi in Lesbos (Thermi V) (after Lamb).

The wide range of decorated spindle whorls from Troy documents weaving. Numerous terracotta figurines were found at Thermi, although not at Troy or Poliochni. Indeed the local variation between the different sites of the Troy I culture is considerable. But apart from the architectural remains, it is the growing interest in metallurgy which distinguishes this culture from its predecessors. Metal now makes its appearance: pins, awls, a dagger from Poliochni, daggers, a spear and a knife from Thermi. A mould for a midrib dagger was found at Troy, and for a shaft-hole axe at Poliochni. An actual shaft-hole axe and a series of daggers and axes, forming an important hoard, were found in levels of Poliochni IV (Red), at the end of this period or the beginning of the next. Stamp seals are also found. No adult burials have been found, but infant burials occur in jars inside and outside houses.

Because it was effectively a one-period site, although with several sub-phases of occupation, Thermi gives the most striking picture of life at this time. The meticulous final report, a model of its kind, documents as fully as the archaeological remains will allow, the life in a proto-urban community of the eastern Aegean at the beginning of the third millennium BC.

The culture of Troy II, of the north-west Anatolian Early Bronze 2 period, marks the zenith of cultural development in third millennium Aegean Anatolia. The fortress at Troy II, the town at Poliochni V (Yellow) and, above all, the rich treasures which they contained, give an impressive picture of wealth and prosperity.

The Troy II culture shows some continuity with its predecessor, although the settlement at Thermi was abandoned, and the Troy I settlement itself destroyed. The distribution of sites has again been given by French (1968, fig. 31). As against 45 settlements for the Troy I culture, he now lists only 10. Only one of these, at the Heraion in Samos, is apparently a new foundation. The others continue from the previous period. Many sites, like Thermi, appear to have been abandoned, for reasons which are not clear.

The citadel of Troy itself was rebuilt. Nearly all the settlement of the period at Troy was excavated (Mellaart 1959a, 136), revealing long houses, one more than 30 m in length, known as the ‘megaron’ or ‘the great hall’. The citadel is still only no m in diameter (fig. 18.13, 2). Several building blocks have been excavated at Poliochni (fig. 6.4), which was larger than Troy, and gives (as in the preceding period) the impression of a town rather than of a citadel. The urban character of the site is brought out by comparing the house blocks of Poliochni (Brea 1955,147, fig. 1; 1964, pl. 25) with the traditional timber frame houses seen at the same time at Sitagroi in eastern Macedonia (fig. 7.8).

The most striking advance now is in the metal work. At Troy, gold beads and a silver bowl were found during the American excavations, and these permit, with fair reliability, the attribution of the great series of treasures found by Schliemann to the destruction levels of Troy IIg. These are all conveniently listed in Hubert Schmidt’s catalogue (1902) of the Schliemann collection, formerly in Berlin and now mysteriously ‘lost’. Treasure A, the Great Treasure (fig. 8.5), contained many vessels of gold, eiectrum, silver and bronze, as well as jewellery, bronze weapons and silver bars (fig. 19.1), and Treasure K included several stone battle-axes of fine workmanship (fig. 18.4), which were obviously weapons of display. The richness of this treasure transforms our view of western Anatolia at this time.

FIG. 8.5 The ‘Great Treasure’ (Treasure A) from the Second City at Troy (after Schliemann).

The splendid golden jewellery found in the levels of Poliochni V (Yellow) (pl. 18.5; Brea 1957) completes this picture. Both these finds were treasures of the living, but they invite comparison with the splendid goods of the dead in the rich burials of the approximately contemporary sites of Alaca Hüyük (Mellink 1956) and Horoztepe in central Anatolia.

Blegen (1963, 80) has emphasised the continuity in the development of the pottery in the early phases of Troy II. It is in Troy IIc that the first evidence is seen for the use of the fast wheel, and new ceramic forms develop, including the typical two-handled cup, the so-called depas. This is a form widely seen elsewhere in Anatolia. Figurines are still found. No cemeteries of this period are known, but a few individual burials of adults occur at Troy.

The final settlement of this culture at Troy II, Troy IIg, was destroyed in a conflagration which concealed the treasures to be discovered by Schliemann. This does not, however, allow us to generalise by suggesting a more widespread ‘wave’ of destruction.

The eastern Aegean towards the end of the third millennium did not, apparently, sustain the dynamic change which marked the earlier years. At Troy the culture continued without serious interruption. French (1968, fig. 48, b.1) in his useful survey, now lists 17 settlements of the culture, of which Troy is again the most important and the most fully investigated.

The Third, Fourth and Fifth Cities of Troy were, like their predecessors, well fortified. Considered as a whole, the pottery of Troy III is practically indistinguishable from that of Troy II (Blegen 1963,96), and the overwhelming impression throughout the period is one of continuity. Blegen reports some changes in subsistence, bones of the deer Cervus dama now being the most frequent. Domed ovens make their appearance in phase IV.

In general, however, despite certain ceramic innovations, the north-west Anatolian Early Bronze 3 period seems to have been a time of consolidation rather than of change.

The new culture at this time marked an expansion in the size of Troy. The citadel of Troy VI, with its impressive fortification walls, was more than 200 m long. Building was of well-dressed stone. Houses and buildings were constructed on a new plan, without regard to the constructions of the preceding period.

The material culture, although exhibiting different forms from the previous early bronze age culture, is not markedly different in kind. An important new feature, however, is the presence of a cemetery of cinerary urns outside the citadel, containing the cremated bones of adults and the unburned bones of children.

The pottery displays a whole new repertoire of shapes, amongst which are those of grey Minyan ware very similar to their contemporaries in mainland Greece.

Although the splendid fortifications of the enlarged citadel at Troy VI testify to a well organised community, the overall similarity in conception to the settlement in previous phases is marked. We do not observe here any indications of civilisation such as are seen in contemporary Crete, or emerge some centuries later in Mycenae. This seems perhaps odd in view of the precocity of Troy II. Yet Troy VI—or for that matter Troy VII in the late bronze age—does not differ very strikingly in kind from its early bronze age predecessors.

No cemetery whatever has been found for early bronze age Troy, or indeed for Thermi or Poliochni. Inland to the south-east, however, are several sites, including Yortan and Ovabayindir, where important cemeteries have been found.

The corresponding settlements are as yet little known, and most of the finds result from illicit excavations, so that associations are not adequately recorded. There were two types of graves: pithos burials were most common, the dead person being inhumed in a contracted position inside a large jar, the mouth of which was closed with a stone. Cist graves, consisting of upright stone slabs, are rarer. The grave goods (Schiek and Fischer 1965) are chiefly of the Troy I and Troy II periods, and may indeed begin before the time of Troy I, although French (1968, 22) has argued that they should in general be set at the time of Troy II. Footed jugs, tripod jars and pyxides with lids, often with heavy incisions, are common. The range of metal forms (chiefly daggers) is wide, and burial seems to have continued at least into the Troy III period (Schiek and Fischer 1965,172).

Further south and well inland, lies Kusura, near Afyon. Kusura A is a cemetery of similar nature, again with both kinds of graves, and dating from the early Troy I period (Lamb 1936b). Kusura B may be equated with late Troy I or Troy II. Still further to the south in Lycia, and like Kusura remote from the Aegean region which is our concern here, is Karataş-Semayük. An extensive pithos cemetery and settlement have been excavated. The site is particularly relevant here for the series of radiocarbon dates cited in chapter 13 from a burnt level of the settlement. The finds in this level are equated by Machteid Mellink (1965; 1967) with those of late Troy I and of the Red phase (IV) at Poliochni, and Kusura period R. The ceramic finds seem to bear this out, and the cemetery and settlement continued in use through the developed Troy II period into Troy IV

Although not directly relevant to the Aegean, the Karataş and Kusura finds supplement the information obtained from the Yortan cemeteries, as well as giving the only reliable radiocarbon dates from Anatolia which can be related to the Trojan early bronze age.

The well-stratified finds at Beycesultan have also been used in this way, and Mellaart has given a valuable synoptic table of Anatolian chronological relations, together with good distribution maps for the Early Bronze 1,2 and 3 periods (Lloyd and Mellaart 1962, 112, 138, 196, 252, 256 and 257; Mellaart 1962, 12, 25, and 44), although he has recently modified the terminology there employed (Mellaart 1970). But it must be stressed that the precise chronological relations between these various areas and the Aegean are unclear and disputed.

More directly relevant to the Aegean are the finds from lasos on the coast of Caria, in south-western Anatolia. Here Doro Levi (1963a; 1967) has excavated an important cemetery of cist graves, mostly rectangular but some of oval or circular shape.

They were constructed of upright slabs, generally four in number, but in one case a dozen slabs were used. The graves were oriented roughly east-west (fig. 19.10,1). The 83 cists excavated each contained one, two or several Inhumations. Children were also buried in this way. Some graves were entirely without goods. Others had one or more pots. The graves contained marble vessels, and a few fragments of obsidian and of copper were found. The most impressive find was a simple dagger of Anatolian type with two rivet holes.

As the only early bronze age cemetery of Aegean Anatolia, as well as the only prehistoric site yet systematically excavated in Caria, lasos Is of great Interest, and its resemblances with the Cyclades are discussed below in chapter 10 and Appendix 2.

In order to deal with the Cycladic resemblances of the cemetery it is necessary to date It In Anatolian terms. The two white-painted vessels (Levi 1967, fig. 163) and the appearance of some of the burnished pottery suggest the cemetery may have begun as early as the Troy I period. The narrow depas-like handles of one flask (ibid., fig. 167, 6) indicate that It continued in use well into the Troy II period. This impression is confirmed by an incised footed vessel (Levi, 1963, fig. 97, 9) which finds a close parallel in the Yellow period (V) at Poliochni (fig. 7.3). (Myrina Museum, Lemnos, no. 926). The characteristic finds of the Early Bronze 3 period of north-western Anatolia are not seen.

Several other prehistoric sites in Caria are now known (Vermeule 1964b), notably Muskebi on the Halikarnassus peninsula, some way south of lasos. The finds are few, however, and add little to our knowledge of the eastern Aegean in the third millennium.

This brief summary has done no more than mention some of the more important excavated sites of the eastern Aegean early bronze age. It has not taken into account the many sites, known chiefly from surface remains, listed by French (1968). These sites are evidently closely related to others further inland such as Beycesultan, and to central Anatolian sites like Alaca Hüyük, and indeed to those of the southern coast like Tarsus or Mersin. Our concern here is with the Aegean, however, and the development of its civilisation. To deal also with these would lead too far afield.

The framework indicated is sufficient to allow the construction of a relative chronology for the Aegean.