The culture sequences established in preceding chapters for each region of the Aegean rest essentially on internal evidence, wherever possible on stratigraphic evidence, with in that region. In this way the regional sequences are logically independent one from another. Fortunately there were contacts and relations between the different areas which make cross-dating possible, and the validity of the internal sequences can be checked. No important contradictions arise. There is controversy concerning only one fundamental point: the relationship of the Troy I culture to the remainder of the Aegean. Mellaart and French take the view that Troy I should be set very early, beginning before the onset of the Helladic early bronze age. At the other extreme are the advocates of a ‘short chronology’, notably Hood and Milojčić, who do not accept the validity of radiocarbon dating, and set many of the Aegean cultures very much later than do other scholars (Milojčić 1967). Fortunately there is a middle way between these positions.

Using the various ‘cultural parallels’—which in only a few cases are actually imports, more often simply similarities of form—the culture sequence of each region may be related to the others, yielding an overall and unified view of the Aegean culture sequence in the third millennium BC. Radiocarbon dates provide further, essentially independent, control of these sequences and their interrelationships.

These different approaches allow the construction of a tentative chronology. This reconstruction of the sequence of events, and their dating, is a necessary preliminary to the consideration, undertaken in succeeding chapters, of the processes at work in the Aegean at this time.

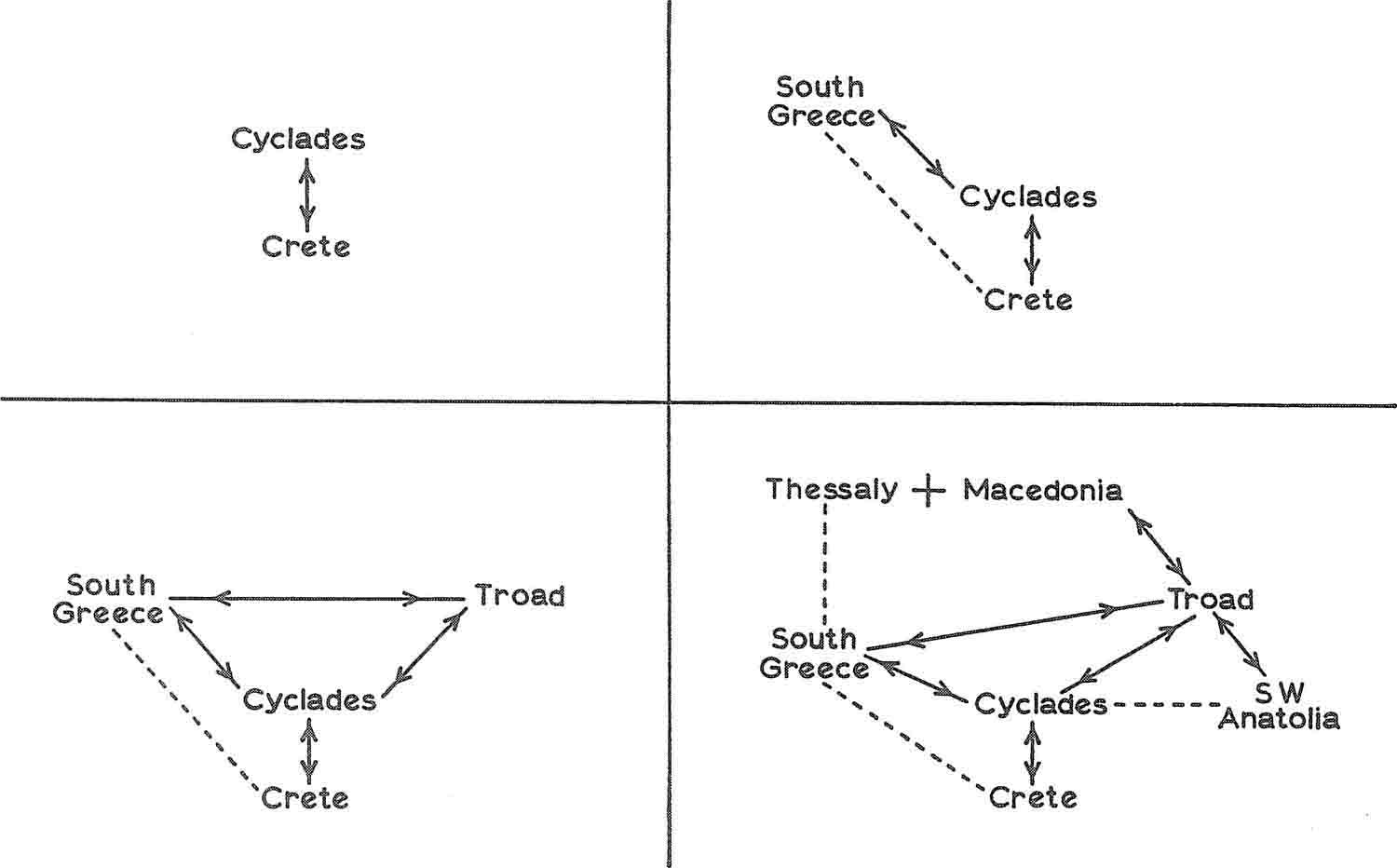

The Cyclades hold a key position since they, alone at this time, had evident contacts with four of the other five regions in the Aegean. Crete, in particular, has strong contacts with the Cyclades, and few with other regions of the Aegean. These contacts can be used to link the Cyclades and the Cretan sequence (fig. 13.1, stage I).

The cultures of southern Greece can then be taken into consideration, yielding a series of chronological links for the southern Aegean (stage II). The cultures of the Troad may be linked with the sequence so established, bringing western Anatolia into the chronological framework (stage III). And finally the two remaining regions, Thessaly and Macedonia, are added. Their interrelations with the other regions are not entirely clear, yet by their inclusion the broad outlines for the chronology of the entire Aegean in the third millennium can be established (stage IV).

FIG. 13.1 The underlying logical structure for the relative chronology of the third millennium. The diagram shows that the relative chronology of Crete and the Cyclades is first determined, and then tied in with south Greece. Other regions of the Aegean can then be related to the chronological framework established.

In general the more recent cross-datings are the more secure, and it will be most convenient to begin in each case with the middle bronze age interrelations.

The terms Early Bronze 1, Early Bronze 2 and Early Bronze 3 for the Aegean are used throughout to designate very approximate periods (not cultures). Early Bronze 2 for instance was the time of the Early Minoan II, the Korakou culture, the principal phases of the Keros-Syros culture (excluding the Kastri and Amorgos groups) and Troy II. But to set the Troy I culture in Early Bronze I together with the Eutresis culture is not to see them as precisely coterminous. The Troy I culture may have begun slightly later than the Eutresis culture, and it clearly persisted well into the time span of the Korakou culture. The most appropriate definition for these terms is to set Aegean Early Bronze 1 contemporary with the Eutresis culture, Early Bronze 2 with the Korakou culture (as, for example, at Lerna) and Early Bronze 3 with the Tiryns culture, together perhaps with the Lefkandi I assemblage.

In the eastern Aegean the terms are often defined so as to coincide with Troy I, Troy II and Troy III–V respectively (Mellaart 1962, 8). The definition followed here is not so very different, if allowance is made for this possible chronological priority of the Eutresis culture over Troy I.

The Second City at Phylakopi yielded, amongst its own characteristic painted ware and quantities of Minyan ware, a good number of sherds evidently imported from Crete.

Nothing was added by the work of Dawkins and Droop (1911, 9) to Mackenzies infinitive statement: ‘Thus the Cretan polychrome ware appears in early floor-deposit of the Second City at a time when geometric ware is still current, though the transition to curvilinear design is in process of being accomplished.... The Cretan polychrome ware probably began to be imported in the early period preceding that for which we have the evidence of floor deposits, and its occurrence attains a maximum in the middle period of the Second Settlement’ (Mackenzie in Atkinson et al. 1904, 260). Mackenzie goes on to state that the Cretan polychrome ware (i.e. Middle Minoan Kamares ware) did not occur in the later period of the Second City, where the pillar houses and frescoes relate to the end of the Middle Minoan period (ibid., 40; 70 f. and pl. III). Melian bird vases, dating from the end of the Second City and the beginning of the Third were found in the Middle Minoan III Temple Repositories at Knossos (ibid., pl. XXI; Evans 1921–25, I, 557).

TABLE 13.1 Imports of Middle Minoan pottery to Phylakopi.

| Phylakopi (Atkinson et al. 1904) | Åberg Chronologie (1933) | Possible Minoan phase |

| fig. 126 | – | Middle Minoan IIa |

| fig. 127 | – | Probably MM I |

| fig. 128 | fig. 332 | MM IIa |

| fig.129 | – | MM Ia (?) |

| fig. 130 (and pl. XXIV, 10) | – | MM IIa |

| fig, 131 | – | Classic MM IIa |

| fig. 132 | – | Classic MM IIa |

| fig. 133 | fig. 329 | Classic MM IIa |

| pl. XXIV, 8 | – | MM II |

| – | fig, 326 | MM I |

| – | fig. 327 | MM I |

| – | fig. 328 | MM II |

| – | fig. 330 | MM IIa |

| – | fig. 331 | MM IIa |

| – | fig. 333 | MM IIa |

Some of the imported Kamares ware is seen in pl. 13, 4. Its suggested dating in Cretan terms may be indicated as seen in Table 13.1.

Thus the early levels of the Second City at Phylakopi may be equated with the Middle Minoan I and II periods.1 And the find in Middle Minoan lb deposits at Knossos (pl. 13, 2; Hood 1963, 94; Renfrew 1964, pl. H’, 4) of fragments of a Cycladic jug, in the Second City curvilinear style, confirms the link. At present we cannot be more specific than to say that Phylakopi II and Middle Minoan I began at about the same time. It is possible that some of the very early Middle Minoan la material (Hood 1963, 93) which some scholars perhaps would class as ‘Early Minoan III’ may antedate the foundation of the Second City at Phylakopi. The presence of eight cups in a cist grave at Alla in Naxos (Papathanasopoulos 1961–62, 131, pl. 63–64) of a form spanning the Middle Minoan I to Late Minoan la periods does not contradict this finding.

The Phylakopi I culture has few links with Crete. A kernos from a very early phase of the First City at Phylakopi (pl. 11, 2; Bosanquet 1896–97, 54, fig. 3) resembles a vessel from Koumasa (pl. 11, 3; Xanthoudides, 1924, pl 1, 4194). And a bottle at Mochlos (Seager 1912, 53, fig. 23, XVI, 15) resembles finds from Naxos and Amorgos (Papathanasopoulos 1961–62, pls. 51b and 61; Tsountas 1898, pl. 9, 26).

Apart from the Kythera discoveries (Coldstream 1970) few Early Minoan II objects have been found outside Crete. They include an incised clay pyxis from Thera (Zervos 1957, fig. 59) and an alabaster bowl, a surface find at Phylakopi (Atkinson 1904, 196, fig. 165; see also Warren 1969b, where other possibilities are discussed). There are, however, numerous similarities linking the Keros-Syros culture finds with those of Early Minoan II. They fall into three main classes: marble figurines, stone bowls and metal objects.

The folded-arm figurines of the Cycladic Keros-Syros culture were certainly copied in Crete. Local marble was available, and a distinct group of figurines, the Koumasa variety, may be recognised (Renfrew 1969a, 18; Renfrew and Peacey 1968). They are generally small in size, very broad in the shoulder and short in the leg. In profile thin and exceedingly flat, they differ from folded-arm figurines of Cycladic manufacture in that the head is usually not separated from the neck except by a light incision (pl. 30, 3, 4 and 6; fig. 19.7). Seventeen of these locally produced figurines are known in Crete, five of them from the tombs at Koumasa, and one from the pure Early Minoan II level in the tholos at Lebena. An example, already mentioned, of Early Minoan I–II date came from the Pyrgos burial deposit. This Koumasa variety must be regarded as an imitation of the true Cycladic folded-arm figurine of which some ten have been found in Crete.

A very important link again is the series of vessels, usually carved in green chlorite schist, which have been found, generally in Keros-Syros contexts, in Naxos, Amorgos, Syros and Melos, and especially in some quantity in Keros (pl. 15, 1; Naxos: Zervos 1957, pl. 30; Amorgos: Dümmler 1886, 17; Syros: Åberg, 1933, 83, fig. 153; Melos: Zervos 1957, pls. 28–29). Many of them show spirals in relief, and incised cross-hatching. As Warren (1965, 10) has shown, the earliest stone vessels of Crete, early in the Early Minoan II period, are of this material and style. It is not clear if they originated in one region rather than the other, but the close similarity is undeniable.

The other stone vessels showing similarities are in white marble—two pyxides from Aghios Onouphrios (pl. 6, 5 and 6; Evans 1895; Åberg 1933, 83, fig. 156)—compare with examples from Syros and other islands (pl. 6, 3 and 4). Several fragments of such pyxides have recently been found in Keros. Spouted bowls, with lugs set near the rim, found for example at Trapeza and Mochlos compare in form with the series from Syros (Pendlebury et al. 1936, pl. 16; Seager 1912, pl. VI; Tsountas 1899, fig. 26). Dr Warren kindly informs me that the Minoan examples differ from the Cycladic in the out-turning spout, flat base, and lug shape.

The third major class of material showing close similarities is the metalwork. Among the copper forms common to the Keros-Syros culture and Early Minoan II are tweezers (Branigan 1968a, 34; Tsountas 1899, pl. 10, 40–22; cf. Papavasileiou 1910, pl. H) and midrib daggers (Classes IVa and IVb of the Cycladic classification, corresponding chiefly to Long Daggers Types III to VI of Branigans Cretan classification: Renfrew 1967a, 11; Branigan 1967a). The close relationship between the daggers of Crete and those of Amorgos apparently persisted from Early Minoan II into the Middle Minoan I period.

One or two further points of similarity must be noted: the curious little stone pestles generally rather attractive in appearance and seen, for instance, in the Trapeza Cave (Pendlebury et al. 1935–36, pl. XIXr), and at numerous other Cretan sites, are common at Chalandriani in Syros and other Keros-Syros sites (Tsountas 1899, pl. 10, 36). They occur in the Korakou culture of the mainland (Blegen 1928, pl. XII, 14–21 and 198). Amongst the pottery, a little footed cup from the Pyrgos Cave resembles vessels from Syros (Xanthoudides 1918, 145, fig. 6, 22 [Herakleion Museum 7496]; Tsountas 1899, pl. 8, 13 and 16). At the very beginning of Early Minoan II at Gournia is a plain-footed cup like an example from the Grotta–Pelos settlement at Pyrgos in Paros (Boyd Hawes 1908, pl. XII, 12; cf. Evans 1921–35, I, fig. 17; Tsountas 1898, pl. 18, 15) and others from Naxos. It is possible that this is the prototype for the little chalices in Vasiliki ware. On the other hand there is nothing particularly Cycladic about the incised pyxis from the Vat Room deposit at Knossos (Evans 1921–35, I, 166), and the ceramic affinities are much less important than those in stone and metal.

These similarities establish the broad chronological correlation between the Keros-Syros culture and Early Minoan II. The later part of Early Minoan II (together with ‘Early Minoan III’) lasted through much of the duration of the First City at Phylakopi. There is no clear indication as to whether Early Minoan II began slightly before the inception of the Keros-Syros culture or vice versa.

Contacts between Crete and the Cyclades, before the time of the Keros-Syros culture, were few, although of course Melian obsidian had been imported into Crete from the early neolithic period. The schematic figurines of Crete have an origin in the neolithic period (Ucko 1968, pls. XXXIX and LIII) just as the Cycladic ones go back to the neolithic Saliagos culture. Cycladic marble vessels have not been found in Crete before the Early Minoan II period.

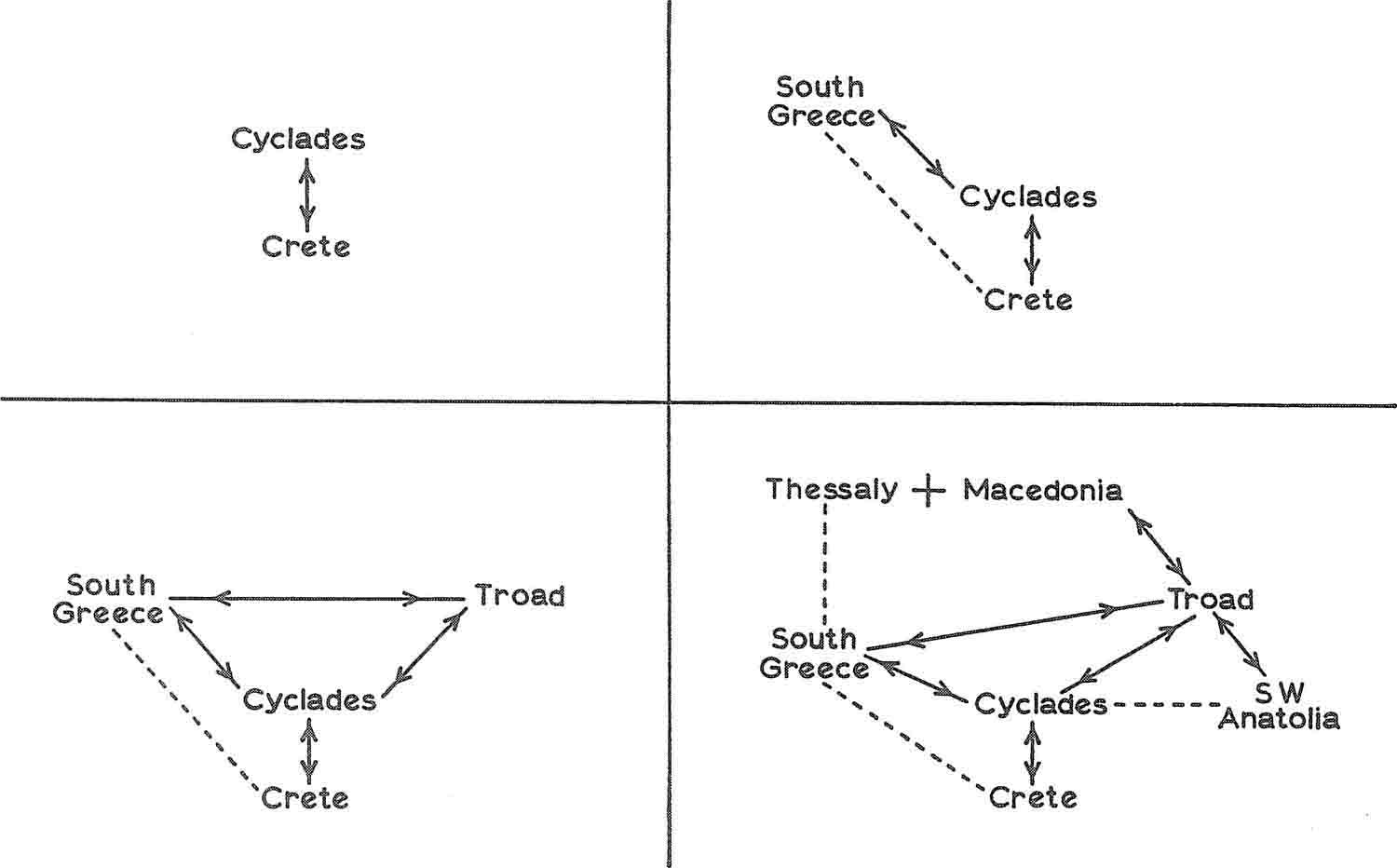

TABLE 13.2 The relative chronology of the Cyclades and Crete in the third millennium BC.

Certain similarities in the pottery are, however, suggestive. Probably the only Cycladic imports to Crete at this time are the five incised bottles from the Pyrgos Cave (pl. 5, 6; Xanthoudides 1918, figs. 8.44–45 and 9.67–69) which are closely paralleled by finds from Antiparos, Paros, Naxos, and Melos (pl. 5, 3–5; Varoucha 1925–26, 104, fig. 7; Zervos 1957, pls. 86–87).

The Cycladic cylindrical pyxis of clay which is never supported on feet finds a rare counterpart in Crete in the incised example from Paterna near Palaikastro (pl. 5, 1; Bosanquet and Dawkins 1923, fig. 2). The decoration resembles that of the poorer Grotta-Pelos pyxides (pl. 5, 2; cf. Papathanasopoulos 1961–62, pl. 65) but in all the Cycladic examples known there are vertical suspension lugs. The Paterna pyxis is probably not an import. In general the Cycladic pyxides have simple flat lids, while the Early Minoan lids have deep-sided flanges coming right down over the body of the pyxis. Another form common to both areas is the spherical pyxis with high suspension lugs (Xanthoudides 1918, figs. 5.9 and 7.33–35; Papathanasopoulos 1961–62, pls. 43b and 67a). The curious Trying pan in the Giamalakis collection (Marinatos and Hirmer 1960, pl. 5), with its idiosyncratic decoration, is without Cycladic or other parallel, and its authenticity may not be beyond question.

The points of contact are not numerous, and do not support the suggestion, made by some scholars, of considerable Cycladic influence upon Crete at this time (Åberg 1933, 242; Hutchinson 1962, 140). Pyrgos ware, for instance, has no counterpart in the Cyclades, nor do the ‘suspension pots’ of Crete have any very close Cycladic parallels. The two regions were certainly less closely linked culturally at this time than in the succeeding period.

The various similarities noted in the two culture-sequences allow the very approximate chronological equation seen in Table 13.2.

The numerous cultural connections between the Cyclades and southern Greece in the early bronze age allow the incorporation of the mainland cultures into the developing chronological framework. It will be seen that direct connections between Crete and mainland Greece are very rare at this time.

No identifiable Middle Helladic pottery has been reported from stratified deposits in Crete, although it is common at Cycladic sites. The characteristic ‘Minyan’ ware had not been so termed in 1904 at the time of the publication of the Phylakopi excavations, where it was known as ‘Lesbian ware’, and ‘does not occur in the lower strata’ (Atkinson et al. 1904, 154, fig. 137 and pl. XXIV, 14). By 1911 the name ‘Minyan’ was being applied, and this ware was commonly found with Kamares ware in deposits of the Second City (pl. 13, 5–6); Dawkins and Droop 1911, 17 and pl. VII, 27).

Similar finds have been made at settlements on many islands (Scholes 1956, 15 f.) including Paros (Paroikia), Naxos (Grotta), Mykonos (Palaiokastro), Siphnos (Kastro), Tenos (Akroterion Ourion) and Kea (Aghia Irini). Only at Aghia Irini is it well stratified (Caskey 1964d, 320 and pl. 49), together with local wares (including Middle Cycladic) and imported Cretan Kamares ware. Minyan ware has also been found in cist graves in Siphnos and Syros (Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 6, 24 and 27).

Cretan pottery of the middle bronze age is found in several contexts on or near the mainland, as well as at Phylakopi. It occurs at Aghia Irini on Kea, at Kastri on Kythera, in poorly documented contexts at Aegina, and most notably at Lerna (Åberg 1933, 40, fig. 64; for Asine, Frödin and Persson, 1938, 275 etc.; for Dendra, Persson 1942, 15, fig. 6.5).

Much of the Middle Helladic matt-painted pottery shows Cycladic influence, chiefly of the painted wares of the First City at Phylakopi. At Eutresis in the early Middle Helladic levels, a series of pots was found with strong Cycladic resemblances. Most notable are the duck vases (Goldman 1931, 184, figs. 255 and 256.1), which are very similar to those of the First City at Phylakopi, and a footed vessel with stamped concentric circles very similar in shape to a pot from Phylakopi I (ibid., fig. 257 and pl. XII, I; Atkinson et al, 1904, pl. IV, 7). At first sight these parallels for Phylakopi I material tend to call in question the Phylakopi II/Middle Helladic correspondence, but this is clearly documented by the Lerna finds. Miss Goldman observed that the Eutresis finds were probably locally made, and not all the stamped and incised pots have good Cycladic parallels (stamped concentric circles do not often occur in the Phylakopi I culture where the best parallels for the shapes occur). Similar decoration is, in fact, found on Minyan ware at Eutresis (Goldman 1931, 143, fig. 197). Only the re-excavation of Phylakopi and the careful distinction between the First and Second City periods could be expected to resolve this problem. At the moment it does not seem necessary to bring the duration of the Phylakopi I culture down into the Middle Helladic period.

The Aegean contacts of the Tiryns culture are not so numerous as those of the succeeding middle bronze age or of the preceding Korakou culture.

At Lerna there is a painted depas cup, and a ribbed depas cup at Tiryns (Caskey 1955a, 37 and pl. 21, 1; Müller 1938, pl. XXXII, 5 and 7). These may be compared with those from Kastri near Chalandriani on Syros and more closely with examples from Early Bronze 3a Beycesultan (Lloyd and Mellaart 1962, 249). The rather squat marble depas from Lerna compares with a pottery one from Kastri as well as with examples from Troy (Caskey 1956, 164, fig. 4; Bossert 1967, fig. 4.1). Duck vases, which probably belong to this period, and which very closely resemble those of the Phylakopi I culture occur in the Athenian Agora, and are numerous at Aegina (pl. 12, 3 and 5). One of those from Aegina, with its curious incised decoration, recalls the little prototype from Kastri on Syros. And the incised wares of Athens and Aegina (pl. 10, 6), especially the conical pyxides and lids, compare closely with the Phylakopi I decorative style (pl. 10, 5).

The characteristic shape of the Phylakopi I jugs (pl. 10, 2), with their backward stretching necks, is seen again at Aegina and in a white-painted example from the Tiryns culture levels at Eutresis (Goldman 1931, 120, fig. 163.2). The contemporaneity of the Phylakopi I and Tiryns cultures, and of both with later Early Minoan II, is established.

The Lefkandi I assemblage also falls at this time, during the Aegean Early Bronze 3 period. As indicated in Chapter 7 and Appendix 2, it has very close affinities with the Kastri group of the Keros-Syros culture. Common forms include stiff-necked jugs, like those of Manika, baking plates and one-handled cups in very shiny, dark fabric. The close Anatolian connections of this body of material have already been stressed.

The Korakou culture is so closely related to the Keros-Syros culture of the Cyclades that their essential contemporaneity is obvious, and forms a basic foundation for any chronology of the prehistoric Aegean. Yet it is important to emphasise that these are distinct cultures and not a single unified whole. The pottery alone establishes the distinction: of the three key forms of the Korakou Urfirnis-ware pottery—the ‘sauceboat’, the footed bowl, and the askos—only the first is common in the Cyclades. The chief occurrences are at Chalandriani in Syros, at Dhaskalio on Keros and at Spedos on Naxos. The footed bowl is seen at Chalandriani and occurs on Antiparos, but is not a common form. Again the Syros type ‘frying pans’ and stamped jars on a pedestal base are very rare on the mainland. No complete Syros ‘frying pans’ have been found at sites of the Korakou culture, although a footed jar was found at Askitario (Theochares 1954a, fig. 26). And folded-arm figurines on the mainland appear to be imports, although they are common enough in Attica and Euboia (fig. 11.5) and occur as far west as Elis (fig. 20.5). Nor are such specifically Cycladic customs as burial in cist graves or built graves of the Syros type, widespread except in Attica until the Middle Helladic period.

Many of the similarities derive indeed, not only from close cultural content but from a parallel development—fortifications, the development of metallurgy, and so forth are functional developments. But even so, we have plenty of specific parallels which are clearly the result of contact.

Among the pottery forms, the ‘sauceboat’—universal in the Korakou culture—is widely found in the Keros-Syros culture as we have seen. Jugs are a common feature in both areas, where they make their appearance at this time. Often they have painted decoration: an example from Askitario compares with those of Syros and Naxos (ibid., fig. 6). A further very widespread form is the one-handled cup, seen on the mainland at Eutresis (where it appears first in the Eutresis culture) and at many other sites (fig. 20.5). In the Cyclades it is known from Syros, Siphnos, Delos and other islands. A single example of this form is known from Crete, from the Early Minoan I levels at Lebena (fig. 20.4, 2). The two-handled cup, an Anatolian form, is found at Orchomenos and at Syros, and its first appearance seems to be at this time. Urfirnis ware is a fabric at home on the mainland, while it is seen at Syros and especially Keros. And in both regions, patterned ware makes its appearance. Formerly thought in the mainland to be exclusively an ‘Early Helladic III’ (i.e. Tiryns culture) feature, it is now seen to have also distinctively Korakou culture motifs also, which relate to those of the Keros-Syros culture.

Stamped decoration of pottery is seen on the mainland, as in the Cyclades, but in detail the forms and decoration often differ: the matter is discussed in Appendix 2.

A second and perhaps more important range of contacts is documented by the metalwork. Almost all the Korakou culture forms are paralleled in the Cyclades—midrib daggers, tweezers, double spiral pins, axe-adzes, as well as flat axes. These forms are discussed again in Chapter 16. Some of them are seen in Early Minoan II Crete, and in north-west Anatolia from the Troy II period onwards. What has been called a culture continuum is seen at this period: the tweezers, for example (figs. 11.3 and 16.7), seen widely in Crete, the Cyclades, and the mainland are a form which probably had a single inspiration.

There are important parallels in stone too. Cycladic folded-arm figurines of marble have been found at several sites in mainland Greece (fig. 20.5). Marble bowl fragments, possibly of Cycladic manufacture, are known from Zygouries and elsewhere. A bowl fragment from Tiryns of steatite or chlorite schist may be compared with those of the Keros-Syros and Early Minoan II cultures. Reference has been made above to the pestles common also in Crete and the Cyclades at this time.

Sealstones are found in mainland Greece in the Korakou culture, and the large collection of sealings from Lerna (fig. 7.7) indicates that many of them had designs similar to (but not identical with) those of Crete. A sealstone from Aghios Kosmas in Attica is Cretan in form and may be of Cretan manufacture (Mylonas 1959, fig. 166.13). The angle-filled cross is a common seal design occurring in the Cyclades as well as in Anatolia and Crete. The decorated bone tubes in the Levkas cemetery (fig. 18.3) are similar to those from the tombs at Chalandriani of Syros.

To list in detail all the points of comparison between the Korakou culture and the Early Minoan II and Keros–Syros cultures would be superfluous. The numerous similarities between them emerged partly as the result of parallel development, but also in consequence of contacts which the actual imported pieces document. Abundant Early Minoan II pottery is found, for example, at Kastri on Kythera: sherds of the Eutresis and Korakou cultures nearby apparently derive from an earlier phase of occupation.

The broad chronological position of the Korakou culture is thus clear. Its beginning may be set approximately contemporary with that of the Keros-Syros and Early Minoan II cultures, and its end is apparently determined (in some places at least) by the inception of the Tiryns culture, contemporary with the First City of Phylakopi.

The Eutresis culture, a dimly known entity, is characterised solely by its red-slipped pottery, several ceramic shapes, and the presence of stamped and incised pottery.

The red-slipped pottery (Eutresis groups III–V), together with the heavy slipped and burnished ware of the preceding group II, may be compared in general terms with the burnished bowls found in settlements of the Grotta-Pelos culture. They have a general similarity also with the burnished pottery of Kum Tepe lb in north-west Anatolia.

The equation is carried a little further by the Palaia Kokkinia finds, which again relate to the Grotta-Pelos culture: spherical pyxides with vertical suspension lugs (Theochares 1951, fig. 25) find parallels in Naxos and other islands. The marble head of a figurine (ibid., fig. 30 c) resembles the Louros type in form, and the Trying pan (or decorated pyxis lid; ibid., fig. 26) like others of the mainland type is to be set alongside the Kampos type ‘frying pans’ of the Grotta-Pelos culture (see Chapter 10 and Appendix 2).

These few points of similarity make a reasonable basis for equating the Eutresis and Grotta-Pelos cultures chronologically. The equation is admittedly an approximate one.

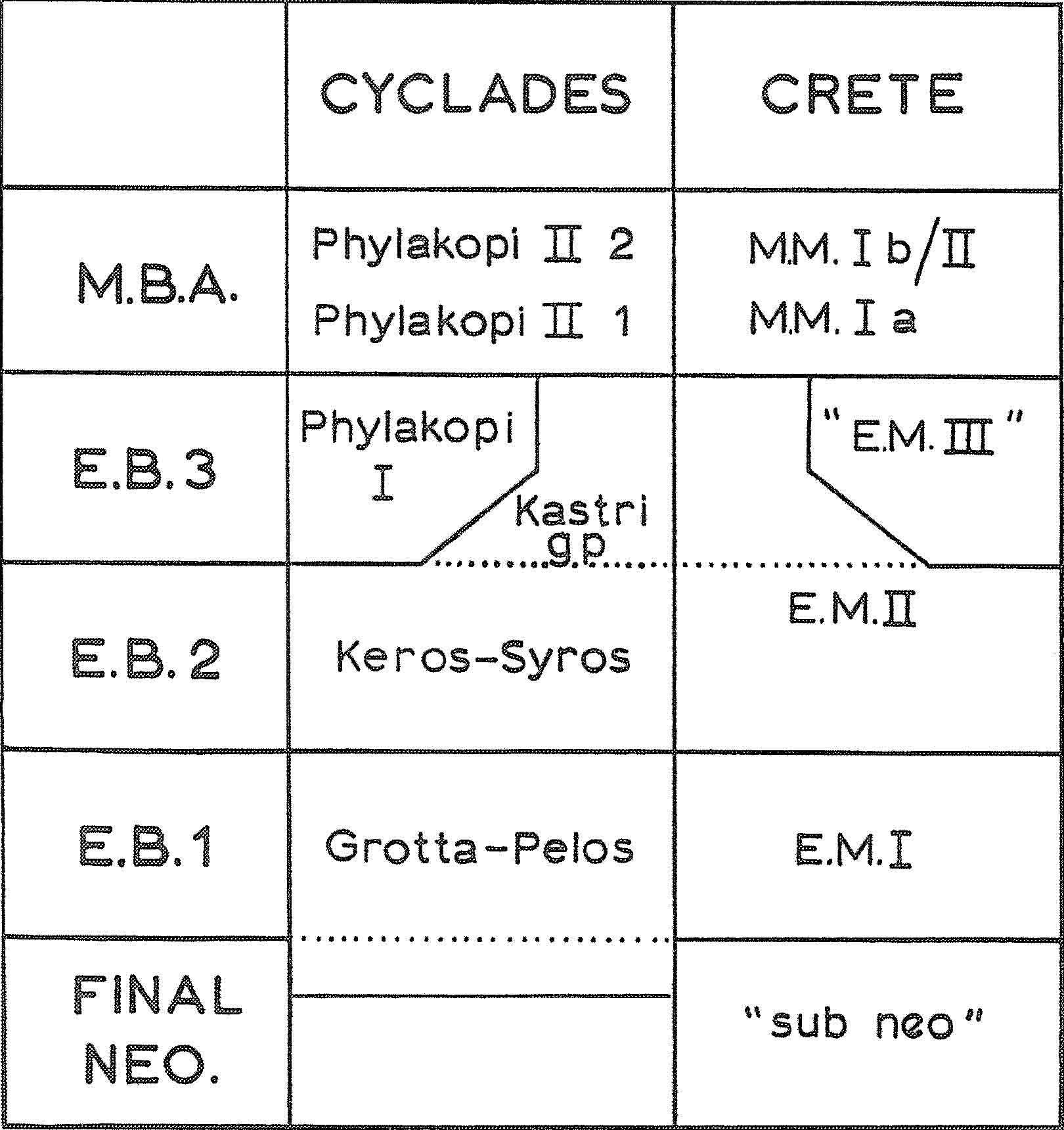

The Aegean links, as so far discussed, give relative chronologies as shown in Table 13.3.

TABLE 13.3 The relative chronology of the Cyclades, Crete and Mainland Greece in the third millennium BC.

The numerous chronological links between the Troy culture sequence and those of the Cyclades and the Greek mainland make chronological correlation easy, at least from the time of Troy II onwards. Before this period the matter is somewhat controversial. Once again it is simplest to consider first the end of the early bronze age, and to work backwards.

The numerous resemblances between the pottery of Troy VI and Middle Helladic Greece are very evident. Similar ‘Minyan’ ware was found in the Second City of Phylakopi, and on several Cycladic sites. Through much of the preceding Early Bronze 3 period, contact was already fairly close.

The external connections of Troy III are admittedly few and rather indecisive: the Aegean wares recovered by Blegen in Troy I levels were still imported, many of them doubtless from the Keros–Syros culture. As Blegen (1951, 10) suggests, Troy III may be set at a time transitional between the Korakou and Tiryns cultures.

With the Troy IV period contacts are much more numerous. The short depas cup of the Tiryns culture (Müller 1938, pl XXXII, 5 and 7) is related to the Trojan form A44. A fragment of Tiryns culture painted ware was found at Troy and is assigned by Blegen to this period (1951, 109 and fig. 170.10). A winged jar from Lerna IV may well be an import from Troy IV (Caskey 1954, pl. 11, b).

The place of the Manika jugs in the mainland sequence has already been discussed: they are closest to those of Troy IV (Blegen et al. 1951, 110).

Contact with the Phylakopi I culture of the Cyclades is established chiefly by the presence of duck vases in Troy IV and V (ibid., 136 and 249, and figs. 170.13 and 243). Those of phase IV at the Heraion in Samos, dated by Milojčić to the Troy IV period (1961, pl. 18), are particularly close to the form of Phylakopi I.

From Kea comes a two-handled cup (Caskey 1964b, 320 and pl. 49, a) comparable with examples in Heraion IV; French (1967b, 36) has compared them also with a specimen from Beycesultan level VI.

A chronological problem which arises in the case of Troy V is that the bowls decorated with a painted red cross, seen in this period, first make their appearance at Lerna in the Korakou culture (Blegen 1951, 227 and 250, and fig. 246; Caskey 1960a, 290 and pl. 69, d). Caskey attempted to solve the problem by regarding the similarity as fortuitous, but it is as close as the others which we have been using. Is it possible that this feature originated in mainland Greece, where painted wares were, of course, a fairly common feature anyway?

These various parallels are sufficient to establish the broad contemporaneity of Troy IV–V with the Tiryns culture, and with the Phylakopi I culture.

The finds from the latest occupation at Chalandriani in Syros, the Kastri group, belong as we have seen to the Troy III and Troy IV periods. Although the short depas cup occurs in Troy II period contexts at the Heraion in Samos, it has similarities with form A37 of Troy IV. The little askoi from the Kastri excavations differ both from those of Phylakopi I and the Anatolian ones, which make their appearance in the Troy IV period. They are smaller and have a loop handle on the back, separated from the spout. The beak-spouted jugs, one with a strongly emphasised beak, do indeed look more Anatolian than Cycladic (Bossert 1967, fig. 3.3) and the long neck and emphasised spout first occurs in Troy III, and is common in Troy IV (Blegen et al. 1951, figs. 72 and 161). These forms occur in the Troy IV period at the Heraion on Samos (Heraion IV: Milojčić 1961, pls. 16, 1; 22, b), and they are not unlike some of the jugs from Manika. The relations of the Kastri group are further discussed in Appendix 2. It is clear that the Kastri settlement at Chalandriani persisted well into the Troy IV period: its chronological overlap with Phylakopi I is clear.

The most famous ceramic shape of Troy II, the depas amphikypellon appears first in phase He, and persists into early Troy IV. It is found at Orchomenos (Kunze 1934, 56, no. 45), probably in a Korakou culture context, and in the Keros-Syros culture fortified settlement at Kastri on Syros.

Further proofs of contact are extremely frequent: the great treasures of Troy Ilg contained a double sauceboat (Schmidt 1902, no. 5863) clearly related to mainland and Cycladic forms. The double spiral pins compare in shape with those of Syros, and there are other resemblances also among the metal forms. The silver tweezers from Troy (Blegen et al. 1950, 281) relate to those of Early Minoan II Crete and the Korakou and Keros-Syros examples already discussed. Once again the parallels in the metal types are too numerous to require listing in detail.

The bone tube from Troy decorated with incised patterns (Schliemann 1880, 526; Schmidt 1902, no. 7960) is related to those of Syros, and a piece of bone decorated with concentric circles (Blegen et al 1950, fig. 365) may be compared with a bone object from Dümmler’s grave D at Kapros in Amorgos (Renfrew 1967a, pl. 4.25). The little spool from Troy Ilg (Blegen et al. 1950, 211) is very similar to the small pestles from Crete, the Cyclades and mainland Greece in the Early Bronze 2 period, to which reference has already been made.

The most important find, chronologically, is the ‘Early Aegean ‘Ware’ imported probably from mainland Greece, which Blegen recognised in levels of Troy I and Troy II. It is discussed further in the next section, and whatever its significance for Troy I, it substantiates that Troy II and the Korakou culture (as well as the Keros-Syros culture) were broadly contemporary.

The most significant ceramic development in the Troy I period is the jug, although the form is seen rather earlier at Kum Tepe and Poliochni I. The jug makes its appearance in Crete in the Early Minoan I period, and despite the manifest differences in the two cultures there are other points of resemblance. The curious barrel shape of Troy I, seen also at Karataş-Semayük (Blegen et al. 1950, fig. 231; Mellink 1965, fig. 32) occurs at Lebena in the Early Minoan I level. So too does the one-handled cup, seen in the Eutresis culture (at Eutresis) and widely in the Troy I culture (form A24; Blegen et al. 1950, fig. 226). Many pots, both in Crete and the Troad, stand on little feet, although this is a feature not seen in the Cyclades or on the Greek mainland. The handled pyxis-covers at Troy find a parallel in the Pyrgos Cave (ibid., fig. 231; Xanthoudides 1918, fig. 9.61). Other parallels have been listed by Warren (1965, 37). They are sufficiently numerous to suggest contact between Crete and Troy at this period, and to indicate considerable overlap in the duration of Troy I and Early Minoan I.

Close similarities are not evident between the forms of Troy I and those of the Grotta-Pelos culture or the Eutresis culture. The broad resemblance in the monochrome burnished wares is, however, inescapable, and includes the use of both horizontal and vertical lug handles. In general the incised decorative styles do not closely resemble one another, but a flask from Thermi is like the Grotta-Pelos bottle form (Lamb 1936a, pl. XIII, 565; Varoucha 1926, 104, fig. 7).

Schematic figurines are abundant in Anatolia at this time, chiefly the figure-of-eight Troy I type (Renfrew 1969a, 27): a similar form was found in the Early Minoan deposit at Lebena. The Cycladic figurines, although similarly schematic, are rather different in shape.

Towards the middle of Troy I some very important new elements occur in the Troad, largely in the form of imports. They are clearly ascribable to the Keros-Syros and Korakou cultures of the Cyclades and the Greek mainland. As we shall see they lead to the very important conclusion that the Korakou and the Keros-Syros cultures were under way by the middle Troy I period.

Blegen is categorical on this point: a number of the sherds of glazed ware (i.e. Urfirnis ware) ‘are recognisable as genuine Early Helladic ware’ (1950, 40 and 54). Three of them are painted (ibid., figs. 241.14 and 252.1–2), comparing closely with the Keros-Syros and Korakou painted ware.

Mellaart and French, intent on establishing a very long chronology for Troy, have tried to set this evidence aside. Mellaart (1957, 79) rather rashly implied that Blegen did not correctly identify the supposed import sherds. French (1961, 117) has examined them himself, and supports Biegen’s identification, but suggests that the context at Troy was unclear.

The Troy evidence is, however, backed up by the ‘sauceboat’ fragment from Thermi V (Lamb 1936a, 90, fig. 524; admittedly later there than middle Troy I) and by imported sherds at Poliochni Blue (Brea 1964, pl. LXXX, a and b) and especially Green/Red, where there is an imported sauceboat' fragment (ibid., pl. CXXIX, c). I have examined this sherd: it is a ‘sauceboat’ spout resembling those of the Keros-Syros and Korakou cultures.

Other forms occur at this time, which apparently appear in Early Minoan II and the Korakou and Keros-Syros cultures. The stone pestles of Poliochni and Thermi are a case in point (ibid., pl. CLXXXVII, 16; Lamb 1936a, pl. XXIII, 30, 56), and the bone tube at Poliochni (Brea 1964, pl. CLXXVIII, 12). The one-handled cups at Poliochni (ibid., pl. CXLIII) look closer to those of the Korakou and Keros-Syros cultures than to the rare examples in the Eutresis culture. While the presence of metal need have no chronological significance, a bird-headed pin at Thermi closely resembles those of bone from Syros (Lamb 1936a, pl. XLVII, 31, 19; Tsountas 1899, pl. 10).

It is concluded that early Troy I is a contemporary of the Early Minoan I, Eutresis and Grotta-Pelos cultures, which end during middle Troy I. Late Troy I is contemporary with what may be termed the Early Bronze 2 cultures of the central and western Aegean.

One minor chronological problem which arises in connection with the Troy I finds is presented by the presence of clay hooks and anchors at Thermi and Poliochni (Lamb 1936a, pl. XXIV, 31, 78; Brea 1964, pl. LIII, a–k). They occur also in Sitagroi Vb and at Michailitch, a site of the developed Cernavoda-Ezero culture in south-east Bulgaria. At Lerna, however, they appear during the Tiryns culture (Caskey 1960a, 297), and at Argissa in ‘Early Thessalian III’ ( Milojčić 1960, 28). Their distribution in the Mediterranean has been well summarised by Evans (1956, 99). An example from Eutresis was claimed by Miss Goldman as Early Helladic I (1931, 196 and fig. 291.1), that is to say of the Eutresis culture, although some of her Eutresis culture material is now assigned to the Korakou culture. It seems likely, therefore, that the absence of this form from Lerna III is without chronological significance.

The stratified finds of this period are so scanty in western Anatolia that only a few general similarities can be drawn. In the first place the open bowls of Kum Tepe lb, with their heavy, burnished fabric and their rolled rims, closely resemble those from Grotta-Pelos settlements in the Cyclades. As already mentioned in Chapter 10, closely similar shapes are found in Emborio VII and VI. Curiously, however, at Poliochni in the presumably contemporary Black period, the rolled rim is not seen, and a slightly out-turned rim, with tunnel lug, also seen at Emborio, takes its place.

David French has emphasised the widespread distribution of these burnished wares (1961, 111 and 196). Certainly the burnished ware of the Eutresis culture, and especially of Eutresis Group II might be related. But these examples lack the rolled rim, and generally are without tunnel lugs. At present such resemblances are rather general, and we must bear in mind also that the rolled-rim bowl probably persisted in the Cyclades through the Troy I period: certainly many of the Troy I bowl shapes are not seen.

There seems little to connect Crete with Anatolia at this time. The Pyrgos pattern burnish, despite a superficial resemblance with that of Beşikatepe is probably of later date than Anatolian examples. The beginning of Early Minoan I thus cannot be fixed in relation to Troy I. It seems that the Grotta-Pelos culture began during the time of Kum Tepe lb and runs parallel to Troy I. The Eutresis culture, following Eutresis Group II, probably began about the time of Troy I.

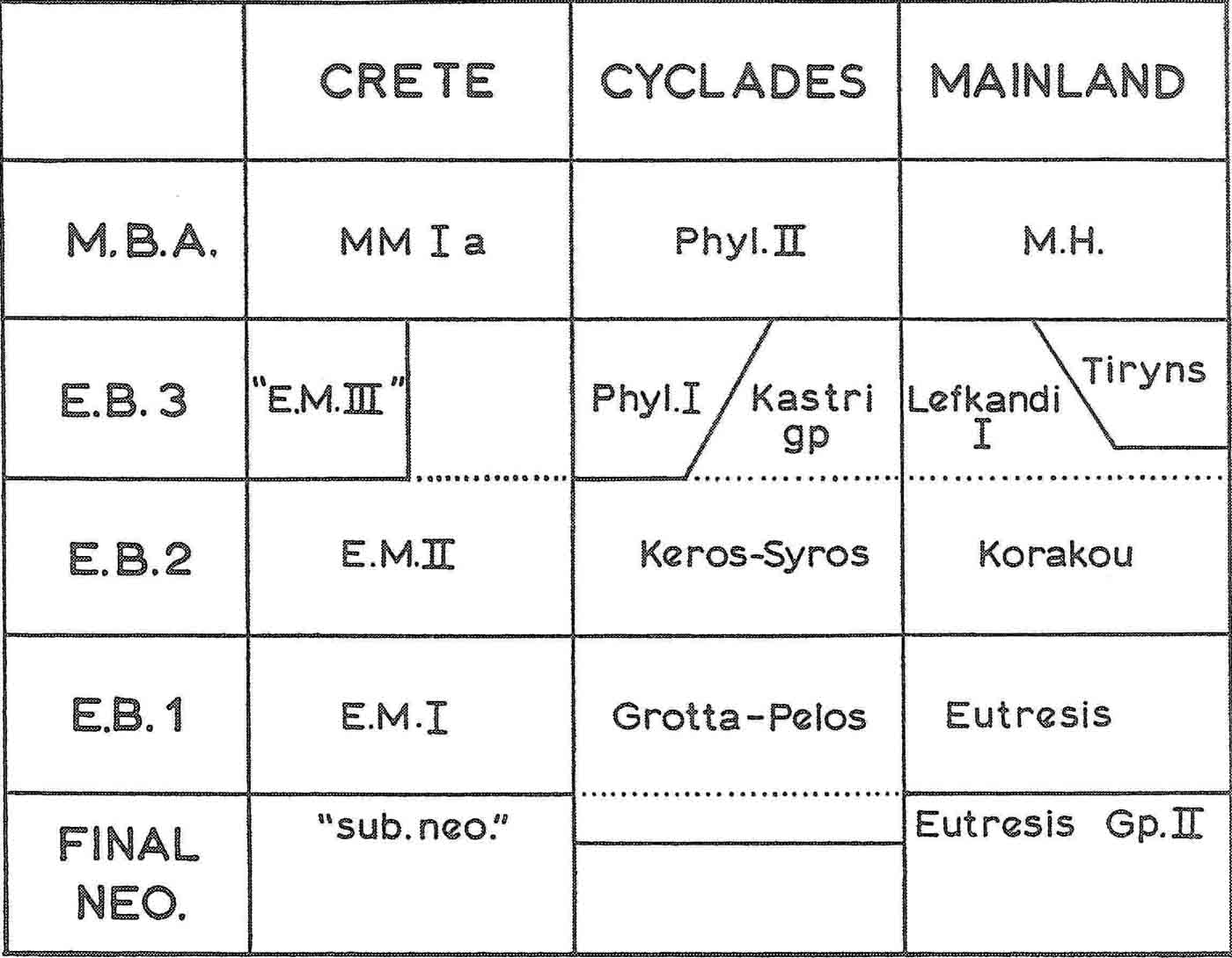

This brief discussion allows the Anatolian sequence to be tied in with that of the rest of the Aegean. The results are seen in the chronological table, Table 13.4.

Thessaly and Macedonia both show, at the beginning of the early bronze age, the same very general resemblances which are seen elsewhere. The plain burnished bowls with incurving rims are related to those of Troy I, and there are other general similarities. The clay anchors, as already mentioned, seem to be without clear-cut chronological significance. At Sitagroi they appear in considerable numbers in phase V.

The Aegean maritime contacts, so common in the later early bronze age between the other regions of the Aegean, seem to be lacking. The Tiryns culture sherd at Kritsana VI is the only evident import from the south Aegean from the entire early bronze age. Thessaly and Macedonia do not participate in the increasing cultural contacts.

The cultures of these regions are to be dated by contact with their immediate neighbours: Thessaly with south Greece, and east Macedonia with Troy. Radiocarbon dates will soon be of help in resolving these problems of dating, and if the excavations at Sitagroi were supplemented by further work in early bronze age levels in southern Thessaly, a solid framework might well emerge. But at present there is little which these regions can contribute towards the general understanding of the chronology of the southern Aegean.

Aegean chronology in the early bronze age has traditionally been based on relations with the ancient civilisations, themselves calendrically dated. In particular the contacts between Crete and Egypt have been of paramount importance. The tenuous nature of such contacts has made possible wide variations in the chronology: the beginning of Troy I, for instance, has been dated by serious scholars to anywhere between 3500 and 1700 BC (Mellaart 1962, 43; Åberg 1932, 104, 123–58 and 163). The Early Minoan I period, to take another example, has been variously dated as follows:

3400–2800 BC (Evans 1921–35, 1, 70)

2900–2700 BC (Pendlebury 1939, 300)

2600–2400 BC (Matz, quoted Hutchinson 1962, 138)

2500–2400 BC (Hutchinson 1962, 138)

2400–2250 BC (Hood 1961)

In 1961, when the first comprehensive list of radiocarbon dates from the Aegean was published by Kohler and Ralph, a new approach became possible. The discrepancies between the radiocarbon dates for Egypt and the Near East, however, understandably gave rise to misgivings, and there were some disturbing inconsistencies. By 1964, using the longer half-life for radiocarbon (5730 years), some reconciliation was possible (Renfrew 1964, 127). But not until the calibration of radiocarbon dates by tree-ring chronology was there hope of a clearer solution.

Although the dendrochronological calibration has not yet been assimilated to archaeology, and cannot be considered firmly established, it does in fact allow a solution of nearly all the outstanding problems. As an experiment it is systematically applied in the next section, and the resulting correspondence between historical and radiocarbon dates is sufficiently close for an integrated chronology to be put forward.

The earliest recognisably Cretan finds in the east Mediterranean are of Middle Minoan II, or perhaps Middle Minoan lb, date. From this time onwards the absolute chronology of the Aegean is closely documented by true cross-datings (Aegean finds dated in the Near East, dated Near Eastern and Egyptian finds in Crete and Mycenae) and has been surveyed recently by Stubbings (Hayes, Rowton and Stubbings 1962).

The Treasure of Tod, apparently accumulated during the reign of the 12th Dynasty pharaoh Amenemhet II contained metal vessels plausibly regarded as Middle Minoan Ha imports from Crete (Kantor 1965, 21). Hood has, however, suggested (1963, 94) on the basis of comparison with recent Knossos finds, that the Tod cups may rather, if they are Minoan, belong to the Middle Minoan lb phase. (These Knossos cups were from the same level as the Middle Cycladic jug cited above (pl. 13, 2), so that the Tod treasure is referable also to the Second City at Phylakopi.) There are problems concerning this treasure; but on the face of it we have Middle Minoan Ha or Middle Minoan lb imports in Egypt before the death of Amenemhet II, around 1900 bc, following the widely accepted Egyptian chronology (Hayes, Rowton and Stubbings 1962, 4). Previously the earliest context for the import of Middle Minoan IIa pottery was set (not altogether securely) in the reign of Amenemhet Us son Sesostris II by finds of pottery at Harageh, and by finds of Middle Minoan II pottery at Abydos and Kahun (Smith 1945, 3; Kantor 1954, 11–13; Pendlebury 1939, 144–45). Commenting on the implications of the Tod treasure, Albright (1954, 33) suggests that while Kamares ware may be imitating designs on metalwork seen at Tod, ‘If the use of these fluted designs continued generations after the attestation of them at Tod, it is perfectly possible that Middle Minoan II did not begin for a good century after the Tod deposit was made. There is no proof Kamares ware was imported into Egypt until the last decades of the Twelfth Dynasty.’ Since the 12th Dynasty is generally dated from 1991 to 1786 BC, Middle Minoan II on this basis might be set nearer 1800 than 1700 BC.

On the basis of these pottery finds (but without the Tod data) Pendlebury (1939, 146) assigned a span of from c. 2000 to c. 1875 BC for the Middle Minoan IIa period. He then put Middle Minoan I at c. 2200 to c. 2000 BC (These dates rested partly, however, on an exaggeratedly early dating for the 1st Dynasty of Babylon). If, following Hoods suggestion, the Tod cups are of Middle Minoan lb form, Middle Minoan lb designs had reached Egypt by 1900 BC. The Middle Minoan I period could well have begun before 2000 BC as Pendlebury suggested.

The other component of the cross-dating, however, must be the evidence in Crete itself. Several Egyptian objects from Middle Minoan contexts have long been known, among the best stratified being a 12th Dynasty scarab and a scarab of the First Intermediate period together with Middle Minoan I pottery at Gournais (ibid., 120). Two recent finds are important. At Knossos, an imported Egyptian scarab of the late 12th or early 13th Dynasty type was found in Middle Minoan lib deposits (Hood 1963, 96 and pl A). Its manufacture may be dated to about 1750 BC. At Lebena, in levels of the Middle Minoan la period, three Egyptian scarabs assignable to the 12th Dynasty were found: the deposit must thus have remained open after 1991 BC (Alexiou 1963, 91).

These finds are supplemented by the much discussed finds of Tholos B at Platanos, where among Minoan objects accompanying burials over a considerable period, imported Egyptian scarabs and a Near Eastern cylinder seal were found. The chronological significance of these finds has been considered by many scholars. Unfortunately, since there was no reliable stratigraphy at Platanos, these finds cannot be given a very precise position in the Minoan periodic sequence. The chronological range of the burials is, however, known: they began in the Early Minoan II period, and the latest finds have generally been attributed to Middle Minoan la (Smith 1945, 10). Branigan has recently shown, however, that some of the burial goods must be assigned to the Middle Minoan Ib/IIa period (Branigan 1968c, 22–24).

The Egyptian scarabs were discussed in detail by Smith and the latest of them was set late In the 12th or early in the 13th Dynasty. A more recent discussion has reached a similar conclusion (Robinson in Branigan 1968c, 12–28). Since the 13th Dynasty began in 1786 BC, It seems that Tholos B at Platanos was still in use at about that date.

The cylinder seal offers an independent line of approach. Most scholars have agreed to assign it to the time of Hammurabi of Babylon (Smith 1945, 15), but more recent work suggests that it may be up to 100 years earlier (Robinson in Branigan 1968c, 29). The high dating for Hammurabi (‘about 2100 BC’) followed by Evans and Pendlebury has now been almost universally rejected, and his accession is now set at around 1800 BC (Smith, 1945, 17; Hayes, Rowton and Stubbings 1962, 42). It thus seems that this cylinder seal may have been buried some time during the 19th century BC.

This discussion shows clearly how uncertain must be a dating on this evidence. If the Tod evidence be accepted (and the vases may well not be actual imports from Crete), then Middle Minoan lb or Middle Minoan Ha influence was seen in Egypt by 1900 BC. The ceramic evidence in Egypt makes it dear that Middle Minoan II pottery was imported by 1800 BC. This might lead us to put Middle Minoan lb from c. 2000 to c. 1900 or 1850 BC, and Middle Minoan Ha from c. 1850 to 1800 BC.

The Lebena scarabs suggest that Middle Minoan la Is not likely to have ended until c. 1950 BC at the earliest. If the end of Middle Minoan lb were set between 1850 and 1800 BC, the evidence of the Platanos finds (accepting Branigans extension of the Minoan range there) would be reconciled.

The Egyptian evidence at present suggests a slightly earlier dating than the Cretan. A range for Middle Minoan lb of c. 1950 to c. 1850 BC is perhaps in best accord with the evidence. Middle Minoan la will then have begun between 2100 and 2000 BC.

These conclusions accord well with those of Hutchinson (1962, 127), and indeed follow essentially the same reasoning. Åström has marshalled the arguments for a later dating—but even if the scarabs at Platanos do belong to the 13th Dynasty (and were thus buried at the earliest around 1750 BC) a Middle Minoan Ha date could be suggested for their burial. Clearly both the date of these scarabs (which, rather than the Babylonian cylinder, argue for a low dating) and the acceptance of some of the pottery at Platanos as Middle Minoan Ib/Middle Minoan II are crucial. Åström, however, relies heavily on radiocarbon evidence which, without dendrochronological calibration, does indeed favour a low dating. We shall see below that the work of Suess and others has completely transformed this line of approach. Åström suggested first 1900, then 1800 BC for the beginning of Middle Minoan la. It now seems that 2000 BC is the latest acceptable date, and 2100 BC may be preferable.

Stratified imports in Crete are much rarer during the early bronze age, and no Early Minoan exports have been found in historically dated contexts in the Near East. Finds of ivory, presumably Syrian or Egyptian, are numerous in Early Minoan contexts and foreign influences are perhaps reflected in the designs of the sealstones. But their inadequate stratigraphic position reduces the value of such observation.

The sole body of evidence of any plausible validity is the series of Egyptian late Predynastic and Early Dynastic vases found, generally in rather unsatisfactory contexts, at Knossos. Pendlebury was very properly cautious about their chronological value (1939, 54–55, 74, 90). Recently they have been authoritatively considered by Warren, who lists 32 Egyptian vases found in Crete which can be set between the Predynastic and First Intermediate periods (1965, 28 f.). Only three were found in contexts which in Crete may plausibly correspond to their Egyptian dates, the others being in contexts obviously considerably later. A diorite pyxis of the 6th Dynasty or earlier was found in the Aghia Triadha tholos in a context there between Early Minoan II and Middle Minoan II, and two bowl fragments came from the upper level of a late neolithic house below the Central Court at Knossos. These two bowls are datable, if Egyptian, to the Predynastic or Early Dynastic I or II periods (Evans 1921–35, II, 16 and 7a and 7c; Warren 1965, 30, nos. 5 and 13). Warren suggests that the upper level of this house is in fact of Early Minoan I date, since a Pyrgos chalice was found there, but such an occurrence is less surprising if a smooth transition from final neolithic to Early Minoan be accepted. A further bowl of syenite, of the 3rd Dynasty, supposedly found in a subneolithic’ context at the South Propylaeon at Knossos has been considered significant by some authors, but Warren emphasises that in fact it lacks any stratigraphical context at all (1965, 30, nos. 6 and 36).

The stratified evidence thus documents:

(a) That Middle Minoan II did not end before the 6th Dynasty of Egypt (hardly a revolutionary conclusion); and that Early Minoan II probably did not end much after that time (2423 to 2263 BC), if one assumes that the bowl at Aghia Triadha was buried within a few years of its manufacture.

(b) The Early Minoan I period at Knossos did not begin before the date of manufacture of the two bowls (‘if Egyptian’) found at Knossos. A possible date for the end of the Second Dynasty is 2686 BC (Hayes, Rowton and Stubbings 1962, 5) and its date could in fact be set much earlier. This still leaves an unsatisfactorily wide range for the beginning of Early Minoan I.

No fewer than 11 of these early Egyptian vases are found in late contexts in Crete, chiefly Late Minoan I contexts, which demonstrates merely that they continued to be prized: an Egyptian vase in the Treasury of St Marks in Venice underlines this point. Many of them were found in unstratified deposits at Knossos, probably as a result of the levelling of the Early Minoan levels there before the construction of the palace. The time range for most of them, in Egyptian terms, is Predynastic to 6th Dynasty If we assume that they arrived in Crete not too long after their manufacture, as Warren urges, they were arriving in Crete from between c. 3100 to about 2200 BC. This perhaps suggests an order of magnitude date for the end of the neolithic and for the Early Minoan period. But regrettably there is no precision in this.

The Cretan evidence thus suggests that the Middle Minoan period began between approximately 2100 and 2000 BC. The beginning of the Early Minoan period may perhaps be about a millennium earlier.

So far there is no material for the early bronze age of the Greek mainland which provides a reliable cross-dating with the early civilisations. The pendant from Asine (Frödin and Persson 1938, 239 f.) now to be placed within the span of the Korakou culture, has indeed similarities with the chlorite schist vessels of the Keros-Syros culture and of Early Minoan II. There seems no reason, however, to search for more distant parallels.

From the Cyclades a single cylinder seal with an unusual suspension loop attracts notice. It is a unique find, and comes from Amorgos together with other objects assignable to the Keros-Syros culture, and perhaps late in its duration (pl. 23, 2; Renfrew 1967a, 6 and pl 4, 19). Frankfort (1939, 70 and 301) classed this seal as of Jemdet Nasr date on account of the ‘loop-bore’ suspension, setting it as early as 3000 BC. But this early date is disputed by Kenna (personal communication; cf. Buchanan 1960, no. 741), and a later one seems more appropriate. In any case there is not sufficient precision to cast much light upon Cycladic chronology.

Two seals from Poliochni have attracted attention. The first from Poliochni V (Yellow), contemporary with Troy II, is of ivory (Brea 1957, figs. 1 and 25), and has a similar suspension loop to the Cycladic one (pl. 23, 3). It has no close parallel in the Near East.

The second is a seal impression, possibly from the Green phase at Poliochni, and attributed by the excavators to an Egyptian origin between the times of the 5th and 8th Dynasties (ibid., 653). But Kenna does not accept this attribution (personal communication) and feels that the object (which does not in fact appear to be an impression, but simply an incised motif) might be of Anatolian origin and considerably earlier. In any case, Brea himself has emphasised its unreliable stratigraphic position,2 and no importance can be attached to it.

The absolute chronology of western Anatolia has been the subject of controversy. Since no direct imports from the Near East have been recognised at Troy or elsewhere, other related sites nearer Mesopotamia must be taken as chronological intermediaries.

There are only two chains of chronological links to consider: via Cappadocia to the Near Eastern chronological system, and via Cilicia to the Levant. The Cappodocian link with Alishar, and these with Troy, have been discussed by Mellaart (1957, 55 f.) They do not seem conclusive in themselves, and rely heavily on the Cilician Interrelations, which are in dispute. The basic problem is to decide how to correlate the Trojan early bronze age periods (Troy I, Troy II, Troy III–V) with the sequence at Tarsus.

There is a good measure of agreement about the absolute chronology of Tarsus. Finds of Syrian pottery, datable to Amuq period H came from the Early Bronze I and II levels at Tarsus (Mellink 1965, no), and bottles like those of Early Bronze II Tarsus have been found in the Early Dynastic cemetery at Ur. Moreover there are connections with Egypt: a Cilician Early Bronze II jug was found at Giza in a context dated to the time of the 4th Dynasty pharaoh Cheops around 2575 BC. A seal from Early Bronze III Tarsus (ibid., 111) can be set in the first Intermediate period (c. 2180 to 2040 BC).

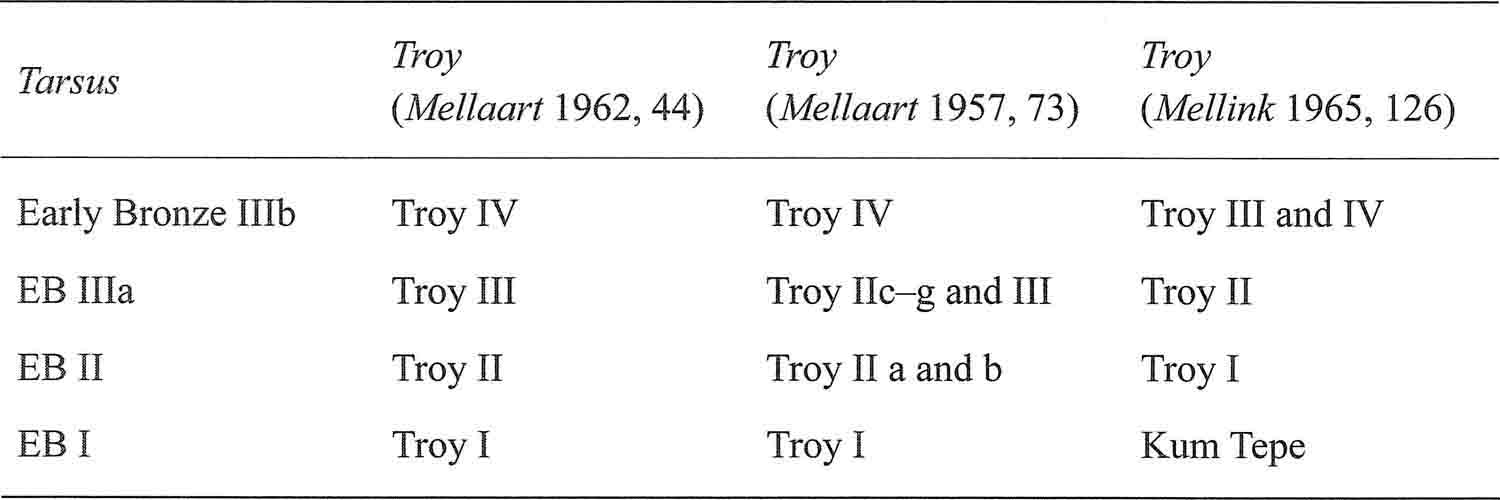

The disagreement arises over the relationship between Troy and Tarsus, and the difficulties in correlating the two areas may be seen from the conflicting equations set out in Table 13.4.

There are undoubted resemblances in the shapes of Troy II and Early Bronze III Tarsus. Mellink (1965, 115) cites the depas (Troy form A45), the plate or platter (Troy Al) and the plain wheel-made bowl (Troy A2). These shapes are not found in Troy I, or at Early Bronze II Tarsus.

Mellaart’s view (1967, 69) is that people from Troy II introduced their culture to Cilicia towards the end of the Troy II period, thus establishing the Early Bronze III culture at Tarsus, while Mellink thinks of a flow of ideas or influences in the other direction: ‘The wheel-made bowls of A2 type are more easily explained as a Cilician fashionwhich found its way to Troy than vice versa.’

It should be noted that initially Mellaart set the beginning of Cilician Early Bronze III contemporary with middle Troy II (Troy lie) while more recently he has set it at the beginning of the Troy III period.

TABLE 13.4 Alternative synchronisms for early bronze age Tarsus and Troy.

The present writer does not feel able to adjudicate on this matter. It will be seen below, however, that the radiocarbon dates can be interpreted as supporting the Troy II/Cilician Early Bronze II equation. But this does not necessarily lead to the very early date for Troy I which Mellaart would propose. In any case the uncertainties in relating the Troy chronology with that of the Near East are so great that the synchronisms add little to what we have already learnt from Crete.

The rather inadequate cross-dating for the Aegean early bronze age has fortunately been supplemented by a series of radiocarbon dates. These form a coherent group, but their correlation with the historic chronology—like that of all radiocarbon dates for the third millennium—presents certain problems.

Many of these difficulties are resolved by the dendrochronological calibration of radiocarbon dates. This allows us to set up a new chronology for the Aegean, using the historic correlations only for purposes of comparison. Such a chronology must at present be tentative, dependent as it is on the still incomplete calibrations. But the striking complementarity of the historic and radiocarbon chronologies indicated below suggests that it should be correct in outline.

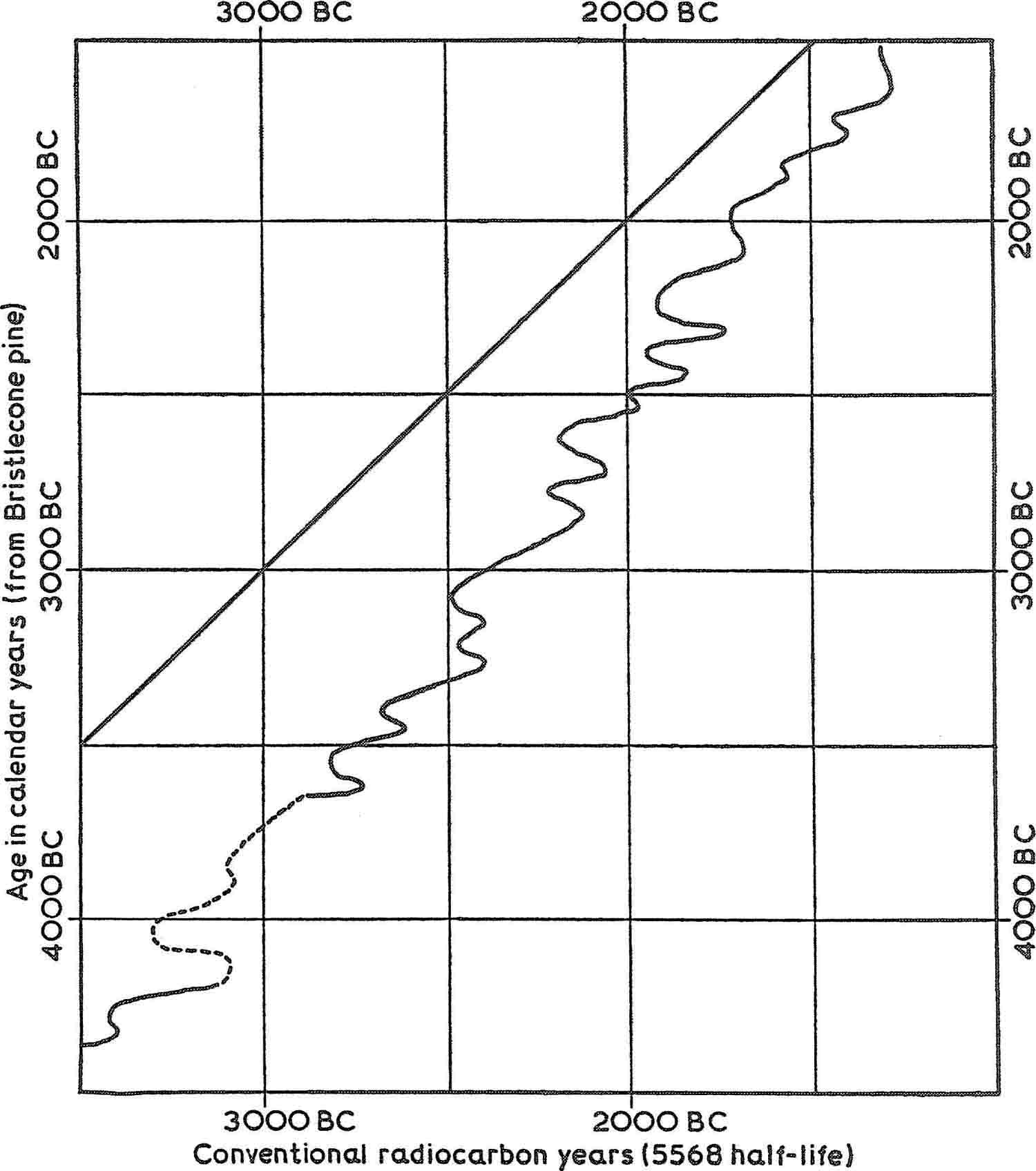

The principles upon which the calibration rests have been outlined by Suess (1967), and its Implications have been set out tentatively for Europe as a whole (Renfrew 1968a; 1970b; 1970c; Neustupný 1968). The calibration chart which has been used here is seen in fig. 13.2. Since it Is itself only a preliminary calibration, the calibrated dates themselves must be used with extreme caution. The Improved harmony between the historical and radiocarbon dates for Egypt which it brings encourages the hope that the emerging chronological pattern will be correct in outline.

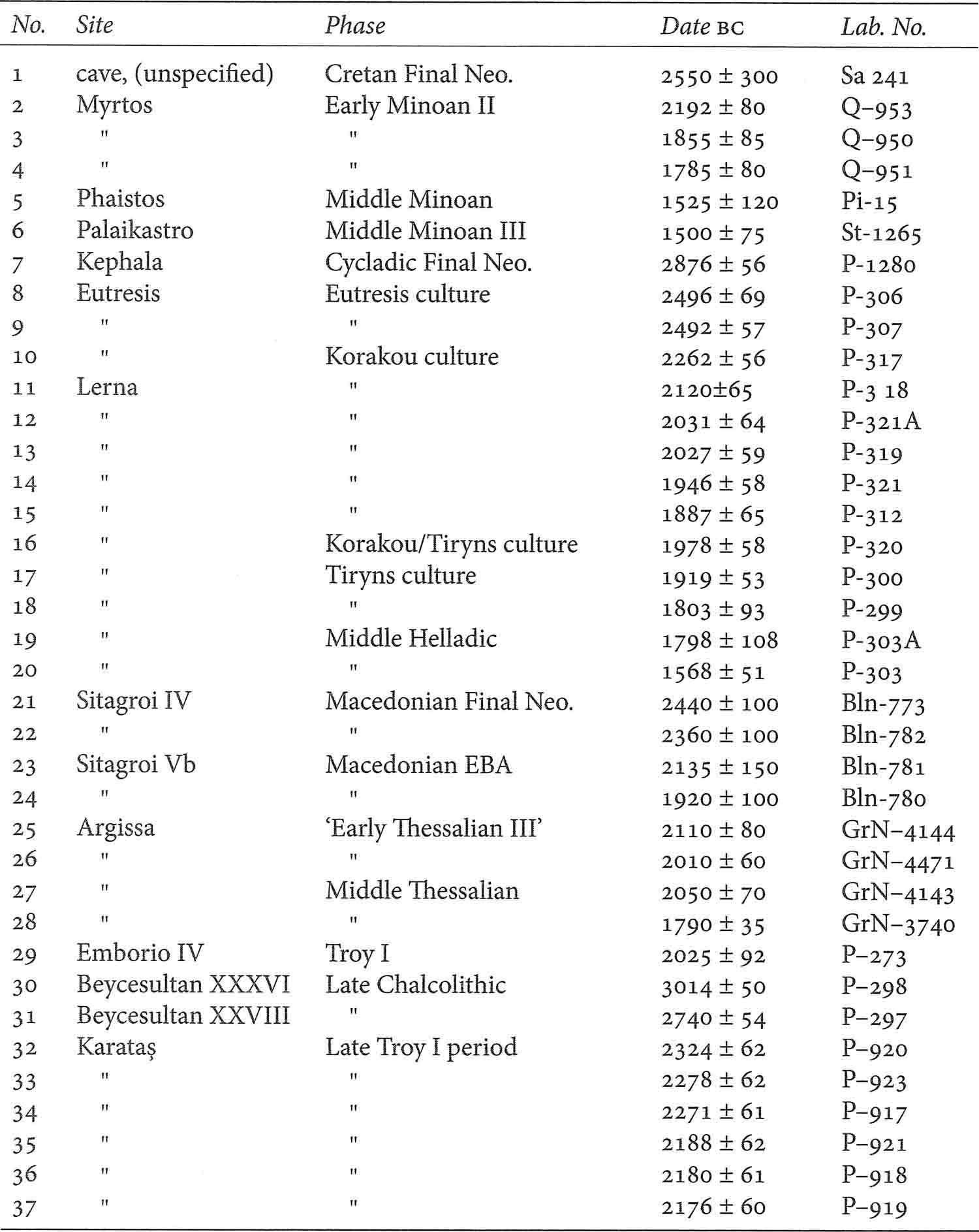

The radiocarbon dates for the early, middle and late neolithic of the Aegean fall comfortably before 3000 BC in radiocarbon years, and they need not be considered here. Table 13.5 lists the available radiocarbon dates which bear upon the chronology of the Aegean early bronze age. Unfortunately the dates for Thessaly and Macedonia cannot yet be related with confidence to those of the southern Aegean, but the series from mainland Greece appears to give a satisfactory coherent picture.

FIG. 13.2 Calibration chart used for the conversion of radiocarbon dates to dates in calendar years (based on work by Suess).

The radiocarbon dates listed in Table 13.5 are shown again in fig. 13.3. The time scale, of course, is in radiocarbon years and a range of one standard deviation has been shown for each date. From this figure emerges an approximate range in radiocarbon years for the sequence in southern Greece.

The implication of these radiocarbon dates, after calibration by means of the curve seen in fig. 13.2, have been applied to the relative chronology between the different regions of the Aegean which was established in preceding sections. The relative and absolute chronologies can be reconciled in a satisfactory manner, and the result is seen in Table 13.6. The radiocarbon chronology for the various periods is entered in the left margin of the table, dates being based on the 5568 half-life for radiocarbon. In the right margin is the suggested periodisation in calendar years, based on the tree ring calibration. Since the calibration remains imprecise in detail, these dates are at present very approximate.

TABLE 13.5 Aegean radiocarbon dates (half-life 5568 years).

FIG. 13.3 Aegean radiocarbon dates for the third millennium BC, indicating the standard deviation for each date. The dates (on the 5568 half-life) are listed in table 13.5.

A calibrated date for the early bronze age/middle bronze age transition of c. 2100 BC is in accord with the radiocarbon date of about 1800 BC. The date for the inception of the Tiryns culture (and Phylakopi I) is more difficult to define since the radiocarbon calibration curve is very irregular in this region. A calendar date of c. 2400 to 2300 BC is suggested.

The beginning of the Korakou culture has been set at c. 2700 BC in calendar years, a date taken also for the beginning of the Early Minoan II and Keros-Syros cultures. Troy II may begin a century or so later, sometime after 2600 BC. This allows us to refer the Karataş dates, set by Mellink late in the Troy I period (although this is disputed by Mellaart), to around the beginning of Troy II.

The beginning of the Eutresis culture is hypothetically set at around 3200 BC. The Grotta-Pelos culture will already have begun by then, and the Kum Tepe Ib culture is still under way. The beginning of Troy I may be set around 3100 BC. To date the beginning of Early Minoan I is rather difficult—perhaps it began at about the same time.

The periods suggested here conform satisfactorily to the radiocarbon dates. For the mainland series, only P–317, for the Korakou culture, a date in calendar years of about 2900 BC, seems rather too early, and this by only a couple of centuries.

Even the much-discussed date for Emborio IV on Chios, now c. 2450 to c. 2300 BC in calendar years, falls within the span of the Troy II period. As discussed above, the persistence in Chios of the Troy I culture, perhaps with a few additional elements, well into the Troy II period seems plausible. The Thessalian dates seem at present rather high: as explained above, this may be due to difficulties in correlating the Thessalian sequence with that of southern Greece.

The radiocarbon chronology harmonises adequately with the chief historical links discussed, namely:

(i) An origin for Middle Mino an la of c. 2100 BC.

(ii) An origin for Early Minoan I very approximately around 3200 BC.

(iii) The equation of Early Bronze II Tarsus and Troy II at about 2600 BC.

The links which Mellaart (1960) proposed, in an article full of penetrating insights, between Troy I and the Balkan chalcolithic are not here accepted. It has been argued that the Gumelnitsa culture was over before Troy I began (Renfrew 1969b). Radiocarbon dates for the Cernavoda-Ezero culture (which follows Gumelnitsa) of 2555, 2435 and 2310 BC (Bln–61a, 61 and 62) give a calibrated mean of c. 3200 BC in calendar years, and support this conclusion. The contemporaneity of the corded ware in Tiryns culture contexts with early corded ware in the Balkans is supported by radiocarbon dates for Ochre Graves at Baia Hamangia in Romania. These are 2140 and 2110 BC (Bln–29 and Kn–38). A radiocarbon date of 2580 BC (GrN–1995), for a sample from the same grave as Bln–29 has not been taken into account) giving a date in calendar years of c. 2600 BC, some two centuries before the beginning of the Tiryns culture.

Table 13.6 embodies the results of this discussion. Taken in conjunction with Table 5.1 for the neolithic period and Table 9.6 for the individual Cycladic islands, it gives for the areas in question what should be a broadly coherent statement of the chronological position. Its compilation fulfils the objectives of Part I of the present work. A discussion of what was really happening during the various periods in question is reserved for Part II.

TABLE 13.6 Chronology of the Aegean in the third millennium BC (Radiocarbon dates on the 5568 half-life; calendar date based partly on the Suess [1967] calibration of radiocarbon).

1 The Cretan period divisions in Table 13.1 must be regarded as tentative. I am grateful to Mr Sinclair Hood for comments on photographs o f the Cretan pottery from Phylakopi; but without the opportunity for him to handle the material these were o f necessity provisional.

2 Brea 1964, 651: ‘è molto singolare e lascia alquate perplessi, soprattutto sulla reale appartenenze del pezzo agli strati (in realtàsuperficiali) da cui proviene, nei quali potrebbe anche rappresentare una intrusione superiore.’