The consideration of civilisation and its origins has so far been in very general terms. We now turn to the specific prehistoric civilisation, the first of Europe, whose origins are our principal concern. The intention now is to outline some of the salient features of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation, in the light of the previous discussion, before turning to that earlier period, in the third millennium BC, when many of its basic features were determined.

Since Schliemann’s discovery of the treasures ‘of Agamemnon’ in the great Shaft Grave Circle at Mycenae and Sir Arthur Evans’s excavation of the Palace of ‘Minos’ at Knossos, the writings of Homer, Hesiod, and the other classical writers who recalled an age of bronze before their own, have taken on a new reality. Today we have a fairly comprehensive picture, which becomes increasingly well documented through the progress of excavation in Greek lands, of the dazzling civilisations of Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece. The precursors of the civilisation of classical Greece by almost a millennium, they shared so many features in common that for some purposes it is legitimate to refer to them together as the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation.

The monuments of this civilisation do not compare in grandeur with the pyramids of Egypt or the temples of the Olmecs and Maya. Nor were there cities in late bronze age Greece which could in any way rival the scale and the order of the huge settlements in the Indus civilisation or the great Mexican metropolis of Teotihuacan. The greatest edifices of Minoan Crete were the palaces of its rulers, and the tholos tombs of its princes. In mainland Greece some of the major acropolis sites were strongholds defended with impressive ‘Cyclopean’ walls. But both areas lack temples or major centres with monumental architecture.

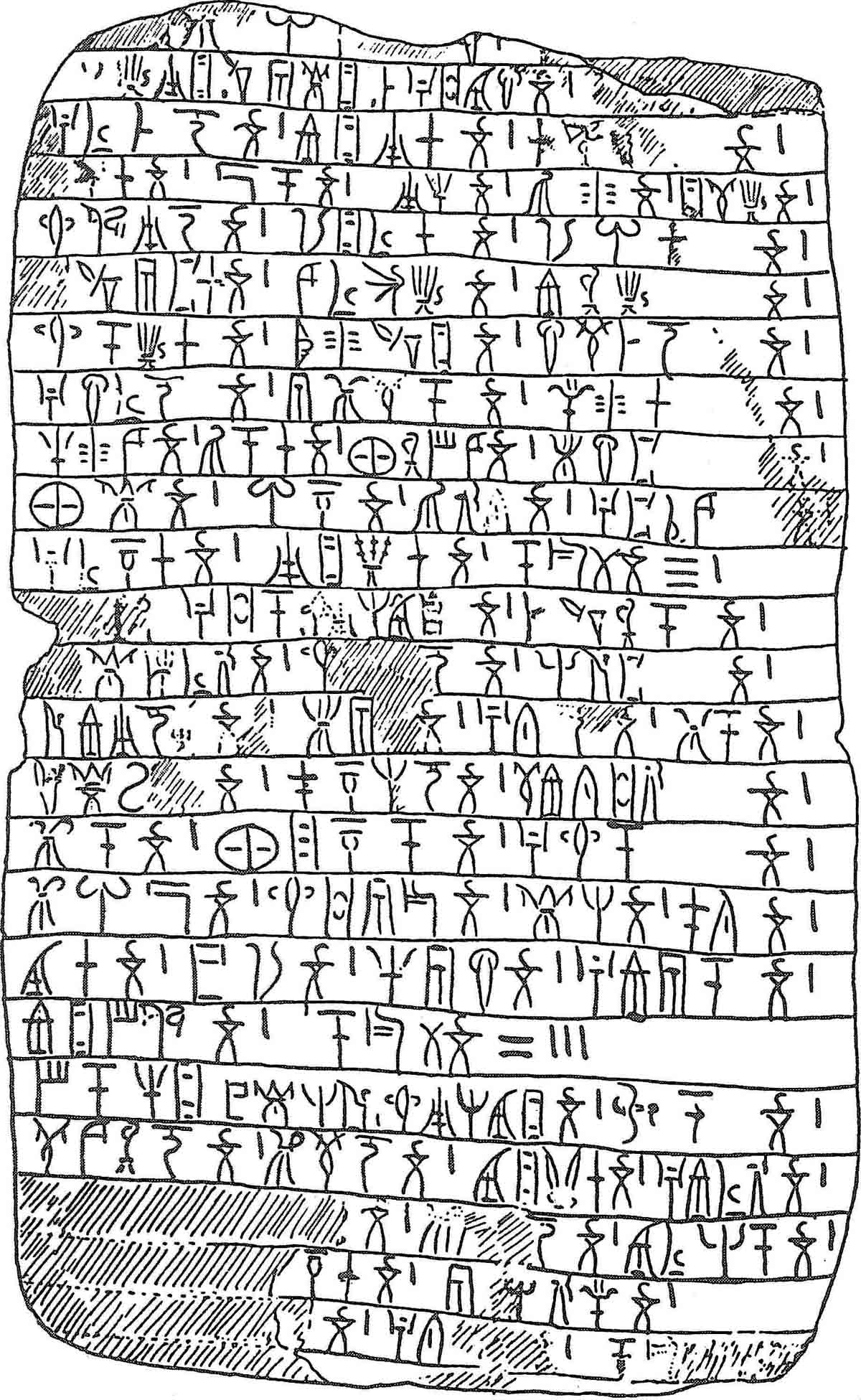

Writing was used for accounting in most of the palaces (fig. 4.3), and this significant criterion for civilisation is supported by the breathtaking sophistication of some of the finds: the exquisite stone vases from the palace at Zakro, for instance, and the consummate metalwork from Mycenae, as well as the delightful frescoes from several palace sites, and especially from Knossos. It is clear that the palace dweller lived in a complicated and comfortable physical environment, calling upon a range of developed craft skills for its creation and maintenance. The social relationships documented by the complexity of the palace lay-out and organisation (fig 4.4), and emphasised by the business-like competence of the written records, are most effectively exemplified by the wealth of the palaces and the splendour of the burials. These again testify to the richness of the symbolic environment. For even in the absence of monumental temples, the projective systems were obviously a real and a complicated part of the environment of the civilised Minoan or Mycenaean.

FIG 4.1 Man’s created environment: prospect of the Northern Entrance Passage of the palace at Knossos (reconstructed by Piet deJong) (after Evans).

The man-made environment of the Minoans and Mycenaeans, in the palace centres at least, was an elaborate and complex artefact (fig. 4.1), which in terms of the discussion in chapter 1 undoubtedly warrants the honorific title of civilisation. It ranks, among the others mentioned, as one of the great early civilisations of the world.

The homeland of the Minoan civilisation was the Aegean island of Crete. In Crete, even during the third millennium BC, and thus before the emergence of the palace civilisation, the finds are all instantly recognisable as ‘Minoan’. That is to say they undoubtedly belong to a single archaeological culture, even though there are some regional variations in types. Minoan contacts overseas were widespread, but only in a few rare cases are sufficient Minoan artefacts found together outside of Crete to suggest the possibility of a ‘colony’. Essentially, despite one or two possible island outposts, such as Thera and Kythera, the Minoan civilisation was restricted to Crete.

Cretan culture may first be termed a civilisation with the emergence of the first palaces, around the beginning of the second millennium. Early writing is seen shortly after this time. Minoan civilisation may be said to end with the final collapse of the palace system in Crete in the later twelfth century BC.

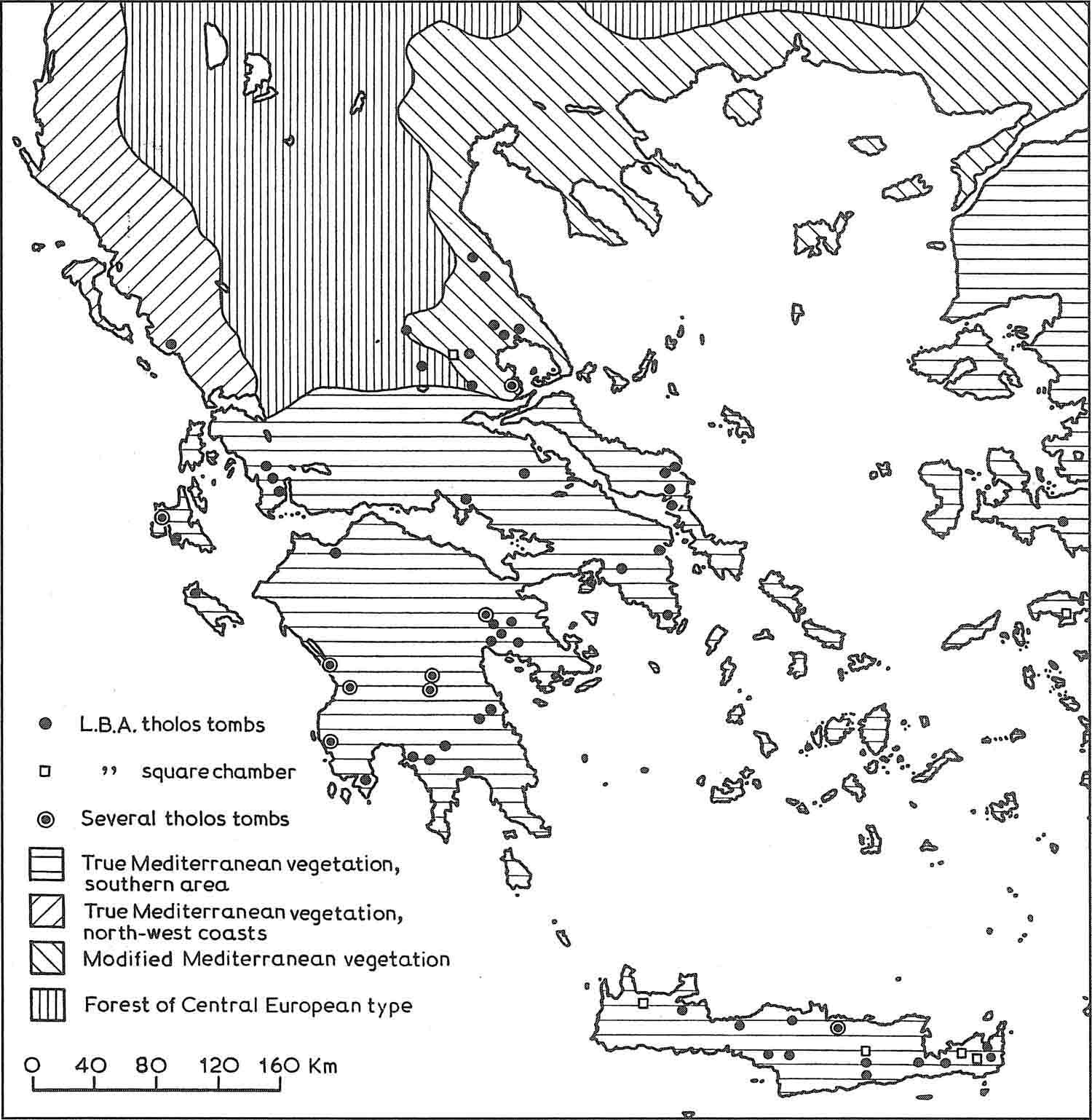

The Peloponnese was the leading area of the Mycenaean civilisation. Many of the principal sites, such as Mycenae and Tiryns, are in the Argolid; others, such as Pylos, are in the west. To the north of the isthmus of Corinth lie the regions of Attica and Boeotia, and these areas, together with the large off-shore island of Euboia, have yielded very abundant finds of the culture assemblage designated ‘Mycenaean’. Sites with finds of essentially Mycenaean character are common also in Thessaly. The distribution of major Mycenaean sites is seen in fig. 15.6, and that of the built tholos tombs characteristic of the Mycenaean (and Minoan) civilisation in fig. 4.2. Finds are less numerous in west-central Greece, although there are important sites in the Ionian islands.

Sites in the Cycladic islands and the eastern Aegean are often designated ‘Mycenaean’, and certainly the way of life which they indicate was similar to that of the Mycenaean mainland. But the finds are by no means identical, and their resemblance should not be exaggerated.

At several sites in both the west and east Mediterranean, numerous Mycenaean finds have come to light (Stubbings 1951; Taylour 1958). At some of these, notably in Cyprus, finds of Mycenaean type are so rich that it is quite possible to regard such sites as within the area of Mycenaean civilisation. But inevitably the local elements of the culture are so marked that the assemblage of finds could not be confused with one from Greece itself. It seems most convenient to regard Mycenaean civilisation as an Aegean phenomenon, restricted sensu stricto to that region. Sites of Mycenaean character lying outside the primary distribution of the civilisation, like the ‘Minoan’ sites outside of Crete, should be regarded as outposts.

FIG 4.2 The vegetation zones of Greece and the extent of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation as documented by the distribution of late bronze age tholos tombs.

The beginning of the Mycenaean civilisation has traditionally been set by the rich finds from the Shaft Graves at Mycenae, discovered by Schliemann, and dated around 1600 BC. No palace remains have been excavated from so early a date, and the more impressive tholos tombs are considerably later. Nor was writing extensively used on the mainland so early. So it is really the wealth of the finds, and the magnificence of their craftsmanship, which has earned the’ designation ‘civilisation’ for the early Mycenaean period. But clearly, on the operative criteria suggested by Kluckhohn, discussed in chapter 1, its use is not merited until the emergence of the palaces and the effective use of writing a couple of centuries later. If we take the enlarged created environment to be the basic and underlying feature shared by all civilisations, the whole new material world which the palace constitutes, and the social world which it reflects, are essential features. In this precise sense, then, we may not call the Mycenaean culture a ‘civilisation’ until the emergence of the first mainland palaces. Unfortunately it is the later period of the palaces which is best understood, and the date of the first Mycenaean palace remains to be established—it may, of course, go as far back as 1600 BC. And the find of a second, earlier, Shaft Grave circle at Mycenae, in use already by about 1650 BC, might be taken to suggest that a princely dynasty, perhaps with a palace of some kind, was already in occupation of Mycenae by that time. At present it is difficult to decide, using the criteria defined, at just what date Mycenaean culture became ‘civilised’. In view of this difficulty and for the sake of convenience, it seems simplest to follow conventional usage and begin the ‘Mycenaean Age’ around 1600 BC.

The end of the Mycenaean civilisation is again defined by the end of the palaces. There are, however, important Mycenaean sites, such as Lefkandi in Euboia, which flourished during the twelfth century BC, after the destruction of many of the palaces elsewhere. The end of the Mycenaean civilisation may most conveniently be set at the termination of the period classified as Late Helladic III C, around 1100 BC.

The Minoan and Mycenaean civilisations shared many features in common. The palace economy of each was, naturally enough, based upon a similar subsistence pattern and craft technology. And, quite apart from the whole range of Minoan exports to the mainland, it is clear that many customs and artefacts of the mainland, imitated those of Crete. Indeed a distribution map plotted for the finds of many types of artefact found in the one civilisation would extend without discontinuity into the territory of the other. The map for tholos tombs (fig. 4.2) is a case in point.

The process of growth in the Aegean seems essentially to have been a continuous one. Any suggested sequence of stages will thus inevitably be somewhat arbitrary. It does seem worthwhile to draw distinctions, since they emphasise some of the features which now seem important emerging during this process of growth.

The earliest palaeolithic finds so far known from Greece are Mousterian. Upper Palaeolithic finds come from various regions of the mainland, from Macedonia and Epirus southwards to the Peloponnese. So far there is no evidence for a dramatic climatic change at the end of the Pleistocene period, nor for a striking shift in the subsistence basis or other aspects of the human adaptation, although intensive exploitation of tunny fish is seen at the Franchthi Cave in the Argolid (Jacobsen 1969). Certainly there was no change so marked as that in northern Europe, where the term ‘mesolithic’ is particularly applicable. There are no phase I finds from Crete or the Aegean islands.

From about 6000 BC village farming settlements are found, based on cereal farming supplemented by leguminous crops. As in the Near East sheep and goat formed about 80 per cent of the livestock, with cattle and pig also kept. Present evidence for the distribution of wild prototypes for these domesticates suggests that several important features of this economy were introduced to the Aegean from Anatolia or the Near East. In the north the villages were of open plan, with pisé houses on a timber frame. In Crete the settlement at Knossos was of agglomerate plan. The distribution or obsidian from the Aegean island of Melos suggests considerable freedom of movement at this time. There is, however, no clear evidence that the Aegean islands (other than Crete) were settled during the first millennium of farming settlement in Greece.

Local variations are now seen in the material culture of the various regions of mainland Greece: the Cretan neolithic differed strikingly from that of the mainland from the outset. In northern Greece, especially Thessaly and Macedonia, tell mounds (cf. fig. 15.2) are of frequent occurrence. In the south they are less frequent, and buildings are more often of stone. New plants, such as the fig, are cultivated, and the first utilisation of the vine, and possibly of the olive, dates from this phase. Sparse indications of copper working are seen from a few sites. Dhimini in Thessaly is fortified, and the first extramural cemetery is seen at Souphli. The trade in obsidian continues, and marine shell is also traded. The Aegean islands are now fairly widely settled. This phase may be dated very approximately (in radiocarbon years) from c. 5000 BC to c. 2500 BC (c. 3200 BC in calendar years).

More complex settlements are now seen in four regions of the Aegean—in southern and east-central Greece, in Crete, in the Cyclades and in north-west Anatolia. The olive and vine are now intensively exploited, and there is a correlation between their distribution and that of the new proto-urban communities (cf. fig. 18.12). Some of these have stone fortifications, a greater density of settlement and notably large central buildings. Copper and bronze metallurgy are now widespread, and trade has increased. This phase covers approximately the third millennium BC. In regions of the Aegean outside the four mentioned, however, the way of life does not differ very markedly from that of phase II.

First in Crete, then in mainland Greece and also in the islands, a centralised organisation emerges, with the palace as focal point. The palace is both the redistributive centre for the economic activities of a region, and the residence of a prince, the leading personage of a society now highly stratified. Craft and technology advance markedly, and in Crete writing is used for records. This is the early phase of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation, which begins in Crete by the twentieth century BC and on the mainland in about the sixteenth.

FIG 4.3 Clay tablet from Knossos, inscribed in the Minoan Linear B script, showing lists of men (after Evans). Length 26 cm.

During the fifteenth century BC Crete adopts many Mycenaean customs and artefacts, and the two civilisations have effectively merged. The Minoan overseas trade of the previous phase is soon superseded by a much expanded Mycenaean trade, in both the east and west Mediterranean. Although the material culture of this phase is simply a consolidation of that of the preceding, it seems possible that there are stronger social and even organisational ties, whose detection and interpretation in the material record offer ground for controversy This phase dates from the mid-fifteenth century to the mid-twelfth century BC.

Many of the important settlements of the Minoan civilisation were destroyed and abandoned around 1200 BC, and very many more sites throughout the region of the civilisation were abandoned during the succeeding century. In particular it is clear that the palace organisation collapsed completely, and with it disappeared such advanced features as the use of writing. Although there was some continuity of occupation in the succeeding ‘sub-Mycenaean’ period, the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation had ended.

During phase II of the developmental sequence outlined above, the cultures of the Aegean may be described as basic subsistence economies. The settlement pattern was one of straightforward farming villages with no systematic variation in size between them. Within them there is little evidence for social stratification or craft specialisation. There was little variety in the subsistence base—effectively cereals and livestock—and limited variation in craft production. In consequence there was no great need for trade or travel, although the notable exception of Melian obsidian shows that these farmers were already accomplished seafarers.

By phase V, however, the Aegean was the home of a full palace civilisation, with a highly structured economy and social system centred on the palace, and with a wide range of sophisticated craft products, made by a competent technology which included metallurgy. Religious observances required a complex symbolism, which was expressed in a characteristic and sophisticated art style. And trading contacts were established with places as far afield as Egypt and Sicily.

It is the transition between these two culture states, the transformation from simple village subsistence economy to full palace civilisation, which we are trying here to understand. Clearly the key to this transformation lies in the intervening period, phases III and IV of the developmental sequence.

At present, and this may be in part due to our very dim comprehension of phase III, it is phase IV which seems crucial. At its beginning the Aegean was the home of rather isolated communities without the effective use of metal and without any evidence for a developed economic or social structure. It is during phase IV that all these features emerged, so that at its end we see the emergence of palace civilisation in Crete.

The focus of attention in the present study falls therefore upon this phase IV, the third millennium in the Aegean, conventionally termed the ‘Early Bronze Age’ An attempt is made to study in detail the changes taking place within the different subsystems of the culture of the time.

The approach here, as the preceding chapters will have made clear, is to favour an explanation in terms of factors working within the cultures, rather than to emphasise the effect of outside influences. But of course the significance of overseas contacts, which were rather numerous, has to be assessed. Most explanations for the origins of Aegean civilisation have in the past emphasised the role of such outside influences. And in order to make the difference between these approaches clear, it seems worthwhile here to outline the argument followed by such explanations. First, however, an important question of interpretation must be clarified.

We are faced in the Aegean today with the impressive, steady accumulation of well-documented evidence bearing on various aspects of the prehistoric past. But it is true to say that our understanding of the prehistoric past has not kept pace with the material now available. The reason for this is a relatively simple one: the theoretical framework for the study has changed hardly at all in the half-century that has elapsed since 1918, and the early writings of Evans, Wace and Blegen.

Sir Arthur Evans applied the term ‘Minoan’ to the culture of bronze age Crete and strictly the word has both a cultural and a geographical sense, referring not only to provenience but to style. The terms Helladic, Cycladic, Troadic, Thessalian (and sometimes Macedonic) are used in an analogous, specialised sense. Evans and Mackenzie, on the basis of the excavations at Knossos, divided the Minoan sequence into three periods (Early, Middle and Late) and each period into three sub-periods (I, II, and III). At the time this was a significant advance and indeed it was followed for a while by Gordon Childe In his classification of the prehistory of central Europe (Danubian I, II, III, etc.).

What Childe effectively realised, however, was the need for separate geographical, chronological and cultural terminologies. The meaning of the term ‘culture’, discussed in chapter 1, was conveniently defined by Childe as a ‘constantly recurring assemblage of artifacts’, and nearly all subsequent definitions amount essentially to this. Cultures, in this sense, have extension in space and time: they are not the same as chronological periods.

Evans’s periodic system for Crete has certain restrictive properties, and really applies in the first instance to Knossos alone. It is universally accepted, for instance, that Middle Minoan II and Late Minoan II are basically pottery styles, and cannot be taken as chronological divisions with wide validity and general application. Early Minoan III is a term which has often been criticised, representing a meaningful chronological division—if at all—chiefly in east Crete. But, despite these difficulties, Evans’s system works in Crete, essentially because the bronze age of Crete as a whole represents the development of a single culture. In other words, the Minoan divisions are sub-periods within a single culture, and regional divisions seem of relatively minor importance.

This is not true elsewhere in the Aegean. For mainland Greece the terms Early Helladic I, Early Helladic II and Early Helladic III were first put forward half a century ago by Wace and Blegen (1918) following the lead given in Crete by Evans and Mackenzie. They have recently been re-defined by Caskey (1960a). But the situation in mainland Greece is not really the same as that in Crete, where we see the evolution of a single culture. Early Helladic I, II and III designate distinct assemblages of material, which are in effect cultures, in the well-defined archaeological sense of that term. While in Crete, therefore, Early Minoan II inevitably follows Early Minoan I, there is in mainland Greece nothing absurd in discussing the possibility that the culture characterised by ‘sauceboats’ and other well-defined features, as seen at Lerna Stratum III (‘Early Helladic II’), may continue in some areas while Lerna and other sites in the Argolid are within the area of a new culture with its own distinctive painted wares—the culture of Lerna Stratum IV (‘Early Helladic III’). Now if ‘Early Helladic II’ and ‘Early Helladic III’ are periods it is absurd to suggest they might in part be contemporary: the numerical designation is employed to denote sequence. Equally it is logically possible—and has been suggested—that at some sites the former culture, ‘Early Helladic II’, and the latter ‘Early Helladic III’ are actually separated by a different archaeological assemblage. Are we then, for this new material to employ a fractional designation? The same problem is seen in the Cyclades where the Grotta-Pelos culture and the Keros-Syros culture may be in part be contemporary. Nothing is gained by designating them Early Cycladic I and Early Cycladic II.

There is no satisfaction in a system where the suggestion that Early Helladic III follows Early Helladic II seems tautologous, or the claim that Early Helladic III could be largely contemporary with Early Helladic II sounds like nonsense.

I therefore suggest that, following standard archaeological practice, cultural designations be used for the mainland early bronze age. For the ‘sauceboat’-using early Helladic II people the name ‘Korakou culture’ is proposed after Blegen’s publication (1921) of a suitable site where in fact the terms Early Helladic I, II, and III were first employed. ‘Eutresis culture’ is suggested for Early Helladic I after the principal site where it has been found well stratified (Goldman 1931), and it may be taken as defined by groups III to IV of the Caskeys’ more recent excavations there. For the Early Helladic III assemblage, as redefined by Caskey (1960a) the term ‘Tiryns culture’ is proposed after the excavation where such material was first published in quantity (Müller 1938). None of these is a one-period site, nor does the terminology imply that they were especially important settlements. It simply allows the independent discussion of cultural and chronological problems.

By adopting cultural designations for the various cultures in the different regions of the third millennium Aegean, we are then also free to use period names, Early Bronze 1, Early Bronze 2, Early Bronze 3, which are defined in chapter 13. Their usage is an approximate one, and depends on the whole series of assumptions about cultural relationships in the Aegean which are made explicitly in that chapter. But the basic terminology must refer to the archaeological material, and that is what the cultural designations effectively do.

Three fundamentally different theories may be expounded for the origins of Aegean civilisation, and any explanation is likely to rest upon one of these, or some combination of them. The first two are, in different senses of the word, diffusionist. The migrationist view, that the key developments towards civilisation were brought about by the arrival of a new population, is diffusionist in the same sense that Elliot Smith was a diffusionist. The second holds that Aegean civilisation emerged as a result of the stimulating influence of the higher civilisations of the Near East. This influence would have come about through trading contacts, and perhaps also through the activities of prospectors for metal who would have travelled in the Aegean before returning to their Near Eastern homeland. The third theory, following the model set up in the last three chapters, seeks to explain Aegean civilisation as essentially the product of local processes. The factual evidence for contact, upon which these theories may stand or fall, is of course a subject for sober assessment. Here it is the theories themselves which we are seeking to contrast.

The migration theories are always, in Greece, bound up with the question of the origin of the Greek language. The presence of non-Greek place names in Greece well before classical times certainly suggests the earlier presence of a population which did not speak Greek. It is widely assumed that this population, or at least its language, was replaced by Greeks, speaking a Greek language, who entered the country from outside. Some scholars set the ‘coming of the Greeks’ as late as the beginning of the Mycenaean period around 1600 BC. Some of those who do not accept Ventris’s decipherment of the Minoan Linear B script as recording an early form of the Greek language can even set their arrival later than this. Most arrival theories, however, set the date some time during the third millennium BC, during, or at the outset of phase IV as defined above, or in conventional terminology, during the early bronze age.

These theories do not attribute the emergence of Aegean civilisation solely to the arrival of Greek-speakers. But often some of the leading developments of the third millennium are explained in this way—and, as suggested above, these are indeed very relevant to this whole question of development and growth towards Aegean civilisation.

In a now classic article, ‘The Coming of the Greeks’, Haley and Blegen (1928) presented the distribution of the ‘pre-Greek’ place names, and suggested that they were the legacy of a population which came to Greece at the beginning of the early bronze age. A decade earlier, Wace and Blegen (1918, 180), on the basis of a study of Aegean early bronze age pottery, had concluded: ‘Further exploration and study will probably show that these three divisions, Early Helladic, Early Cycladic and Early Minoan Ware, are all branches of one great parent stock which pursued parallel but more or less independent courses.’ Following this argument, it would of course be perfectly reasonable to attribute some of the new features of the period, such as metallurgy perhaps, to the cultural equipment, if not the innate dynamism, of these arrivals.

Following the classic exposition of this theory, a different pottery style, Minyan ware, which is typical of the middle bronze age of the Greek mainland, would indicate the arrival of the Greeks themselves. ‘The period of Minyan ware indicates the introduction of a new cultural strain, the origin of which is not yet clear, though some indications point to Phokis and others to the eastern shores of the Aegean as its home.... Though Early Helladic Ware disappeared it need not necessarily mean that the race that made it was extirpated, for it seems inconceivable that a race so numerous and so widespread, to judge merely by the distribution of Early Helladic Ware on the Mainland, could have been obliterated’ (Wace and Blegen 1918, 189).

In the half century since those remarks were written, and largely through the researches of its authors, it has become clear the Minyan ware does not have the great significance which it once seemed to possess. But the citation is an important one as indicating a migrationist train of thought, which has been followed by other writers.

The changes occurring in the Aegean at the beginning of the third millennium have been attributed, by different authors, to the arrival of a new population from at least four different directions. It may be worthwhile to highlight here some of the evidence on which these views rest.

The view that the onset of the Aegean early bronze age was significantly affected by the arrival of immigrants from the north offers the hope of a correlation with the linguistic problems arising from the distribution of the Indo-European languages (Crossland 1967; Gimbutas 1965). But although Mylonas (1959, 27 and fig. 21.2) has compared some forms of the Korakou culture at Aghios Kosmas with those of the Baden culture in the Balkans, and supposedly Balkan cord-impressed pottery has been found at a few sites (Milojčić 1959, 27 and fig. 21.2; Goldman 1931, 122, fig. 169) the theory can explain only a few of the features seen in the Aegean at this time.

In the early years of his excavations in Crete, Sir Arthur Evans was impressed by a number of features for which parallels could be found in Egypt and especially in North Africa. He did not take the view, argued by Elliot Smith, that the Minoan civilisation was the direct result of influences from Egypt. But he did point out that the round tombs of the Mesara in Crete might be comparable with certain round tombs in Libya, and that the penis sheath, seen in Minoan Crete, was also worn in Libya. These possibilities, however, were not greatly emphasised by Evans, and the theory has found few advocates.

In recent years Weinberg (1965b, 308) has ingeniously proposed that apparent similarities between Aegean early bronze age finds and those of the Ghassul culture of Palestine suggest an immigration from that general area: ‘Thus it is possible now, even more than in 1952, to demonstrate the parallelism between the general development in the Aegean, beginning with the Aceramic Neolithic period, and in the Near East. The Aegean was the recipient of repeated waves of migration from Anatolia and Syro-Cilicia in particular, as well as of cultural influences that came independently of actual migrations’. This then is the background, and Weinberg has listed a number of forms in the third millennium Aegean which may be assigned parallels at Ghassul—‘bird vases’, mat impressions on the base of pots, high pedestal feet for chalices, suspension lugs, clay ladles, pattern-burnish, cheese pots, impressed spirals, contracted burial in cist graves, pithos burial, pyxides, and incised decoration (Weinberg 1954, 95; 1965b, 302). The theory is an interesting one, but a detailed exposition of it might prove more persuasive. At present Weinberg is its chief exponent.

Current archaeological opinion favours much more strongly some transfer of population from Anatolia to Greece, Crete and the Islands at the beginning of the early bronze age. The position has been cautiously stated by Caskey (1964a, 36): ‘Early in the third millennium a current of new influences seems to have spread from north-western Asia Minor and Macedonia and southward, sporadically and somewhat diluted, into central Greece. About the same time, or perhaps a little earlier a parallel movement must have brought people to the small islands of the Aegean, where Neolithic settlements appear to have been scarce. Crete ... was also affected. Logic suggests that the first Early Helladic occupants of southern Greece itself must likewise have come by way of the islands, but at each step along this path we find the evidence less convincing.’

Emily Vermeule (1964a, 26) writes more positively: ‘A variety of movements spread from Anatolia across the Aegean islands.... Crete perhaps received a group of Anatolian sailors, and Anatolians certainly settled the largely unexplored mounds of Macedonia and Thessaly. They were not all the same racial stock ... nor did they speak precisely the same language or make the same objects’

Gordon Childe who, as we shall see, had his own very persuasive diffusion theory was more cautious (1957a, 66): ‘A closer study of the pottery, however, shows that no one Anatolian culture was reproduced on the European shores. If a migration from Asia Minor be assumed, it will be necessary to postulate several streams with different starting points.... Perhaps, then, the striking agreements could be explained as parallel adjustments of related cultures when visiting merchants and prospectors from the Levant and Nile introduced metallurgical and other techniques....’

The evidence supporting these various migration theories will be reviewed later—at present it is sufficient to bring out the theoretical framework, which is, of course, a rather different one to that adopted in the present work.

A general weakness of the migration hypothesis, however (with the exception of theories placing the origin of the migration in Egypt or the Near East), is that, even accepting that an incursion of people took place, this does not explain how a significant cultural advance came about unless it can be shown that the arrivals possessed in their homeland skills which at that time were lacking in the Aegean. Of course, in fairness, it must be pointed out that in some cases the theory seeks to explain a linguistic change rather than a cultural one. But sometimes there is an implied appeal to innate cultural qualities which the immigrant race or people may have possessed.

The diffusion theory overcomes this weakness, for it does not simply insist that the Aegean cultures were in contact with the inhabitants of other areas. An essential tenet is that the significant and determining contacts were with ‘centres of higher culture’, and that through these contacts technological and other advances were transmitted to the Aegean. The focus of interest shifts, therefore, from the immediate neighbours of the Aegean to Egypt and the Near East (and specifically Sumer) where the two earliest civilisations of the Mediterranean were developing.

This theory was compellingly propounded by Childe (1936a, 169 f.). He argued that the great irrigation civilisations of Mesopotamia, the Nile and the Indus arose essentially independently. But this theory was not extended to other civilisations of the ancient world. It is here that the diffusion theory emerges: ‘But once the new economy had been established in the three primary centres it spread thence to secondary centres, much like Western capitalism spread to colonies and economic dependencies. First on the borders of Egypt, Babylonia and the Indus valley—in Crete and the Greek islands, Syria, Assyria, Iran and Baluchistan—then further afield, on the Greek mainland, the Anatolian plateau, South Russia, we see villages converted into cities and self-sufficing food-producers turning to industrial specialisation and external trade. And the process is repeated in ever widening circles around each secondary and tertiary centre.... The second revolution was obviously propagated by diffusion; the urban economy in the secondary centres was inspired or imposed by the primary foci. And it is easy to show that the process was inevitable.... In one way or another Sumerian trade and the imperialism it inspired were propagating metallurgy and the new economy it implies.... These secondary and tertiary civilisations are not original, but result from the adoption of traditions, ideas and processes received by diffusion from older centres. And every village converted into a city by the spread became at once a new centre of infection.’

FIG 4.4 The Middle Minoan palace at Mallia (with later additions) (after Marinatos and Hirmer).

Childe’s very persuasive model for the dissemination of civilisation has been adopted by most of those considering the origins of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation. It is not, however, accepted here, since, as we shall see in chapter 20, the evidence for it does not appear convincing. The model outlined in chapter 3 is intended as an alternative to that proposed by Childe, although it may not have all the latter’s compelling simplicity. Childe’s theory gives the clearest available expression of the diffusionist case, an explanation which would be accepted in outline by most of those who feel that the migration of people may also have played some role in this process.

This brief survey of some of the principal features of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation, and the explanations that have been adduced to account for its early origins, concludes the introductory section of this book. In Part I, which follows, the material and especially the culture sequence for the different regions of the Aegean during phase IV, in the third millennium BC, will be discussed. As explained above, this was the crucial phase for the emergence of Aegean civilisation, and the solution to many of these problems must depend upon the assessment which is made of it. In Part II the various subsystems of the culture, as defined in chapter 2, are considered in turn, and an effort is made to see how their growth and interactions brought about the emergence of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation.