It is with the Keros-Syros culture and its contemporaries that we can begin to speak of a Metal Age in the Aegean. Only now are metal types numerous, and they are accompanied by a whole range of new, almost international ceramic forms that are seen throughout the Aegean. The ‘sauceboat’ may be a Helladic invention, but it is widespread at this time. The one-handled cup (fig. 20.4, 1–4) is perhaps an Anatolian product on the other hand, while undoubtedly Cycladic in origin is the marble folded-arm figurine so often found beyond the Cyclades (fig. 19.5). It is therefore not possible to regard these widespread and contemporary types as originating together in a single area of the Aegean. Other features—the depas, the beaked jug, and especially the widespread practice of metallurgy and the ubiquity of such forms as the slotted spearheads—testify to the very widespread contacts in this era, and we have now what might be termed a cultural continuum embracing mainland Greece, west Anatolia, the Cyclades and even to some extent Crete in what can conveniently be labelled the Early Bronze 2 period.

This is a new phenomenon, for the preceding phase shows very little of this international spirit. Indeed in Greece, Crete and the Cyclades, talk of Early ‘Bronze’ 1 is rather pointless, for metallurgy itself was scarcely practised, and certainly not bronze metallurgy.

The Cycladic aspect of this new Early Bronze 2 continuum is seen in the Keros-Syros culture, which must now be examined.

The evidence which has been accumulating in recent years for the existence of this culture in other islands than Syros is important in several ways. Most of all perhaps it demonstrates that the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros cultures are chronologically distinct, and not mere complementary regional distributions. In the following account it is this aspect which will be brought out, for a thorough discussion of the Syros material must await Fischer-Bossert’s full publication of Tsountas’s finds, and will be most authoritatively presented by her. It is not therefore proposed to discuss every type in turn here, but simply to choose those that seem to have a wider significance. Fortunately Tsountas published several complete grave associations, and from their homogeneity the contemporaneity of the main types may be deduced.

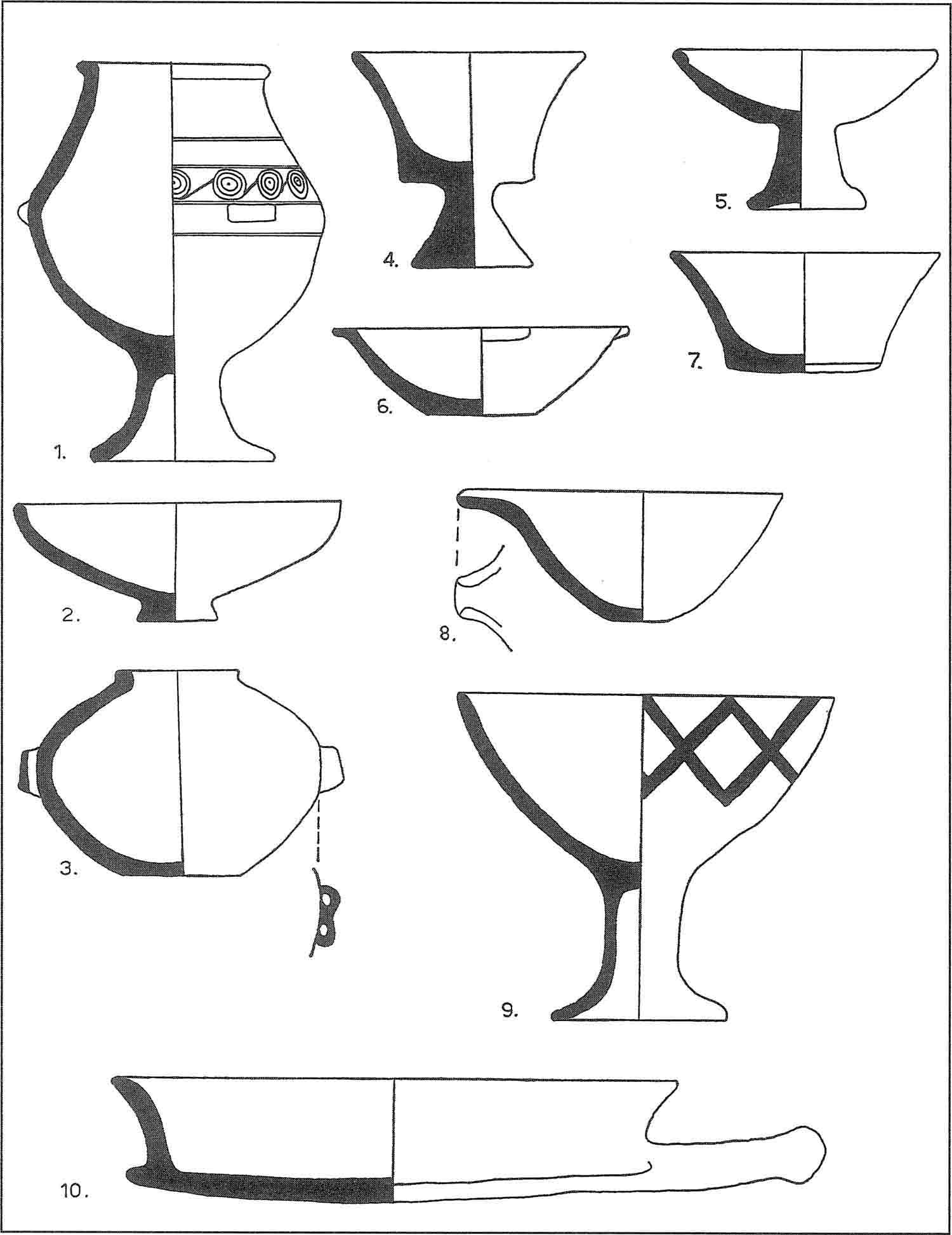

FIG. 11.1 Forms of the Keros-Syros culture from Chalandriani. No. 9 has dark-on-light painted decoration, 4 to 8 are of marble. Scale 2:5.

It is perhaps worthwhile first to define more clearly the Keros-Syros culture in contrast with the Grotta-Pelos culture. As explained in Chapter 9 the division rests in the first instance on the grouping of grave finds. Whereas the Grotta-Pelos tombs contain cylindrical and spherical pyxides, necked jars often on pedestals, herring-bone decoration and such marble types as the kandila, the flat-based rhyton and the schematic figurine, the Keros-Syros culture has none of these things. The pyxides are lentoid rather than cylindrical, the footed jars are different, and there is a complete new repertoire which is entirely characteristic (figs. 11.1 and 11.2). The fabric is itself recognisable: the red-brown surface has a lustre which arises not merely from the application of an Urfirnis coating, as some have thought, but from a combination of slip and burnish. It is rather different from the burnished surface of the finest Pelos pots, but there are sometimes confusions between it and the later early bronze age burnished wares of Phylakopi I type. The stamped spiral (more often in fact concentric circles) and the painted wares are a new feature now. But to take any single technique as diagnostic would be a mistake, as is seen below for the stamped decoration. There is also a range of new forms in marble. Most prominent among them is the folded-arm figurine, which in view of its importance chronologically and for recognising the culture, will be separately discussed.

The starting point for any discussion of the Keros-Syros culture must be the abundant finds from the cemeteries at Chalandriani itself. These, as will be seen, form a fairly homogeneous group, which has close parallels in the finds from Naxos and Siphnos. On the other hand, the finds from Amorgos, while sufficiently close to be classed within the Keros-Syros culture, include also several rather late features (such as the Phylakopi I duck vase) suggesting that cist burial may have continued there until the end of the early bronze age, and indeed into the middle bronze age period. This material constitutes the Amorgos group of the Keros-Syros culture (pl. 9, 5–6).

At Chalandriani itself, the recent finds from Kastri, the fortified stronghold there, show features not observed in the cemeteries excavated by Tsountas. Since they evidently date from the last period of use of the fortress they may plausibly be set at the end of the occupation which the cemetery finds document: this late position is supported by the eastern Aegean analogies for the finds. This assemblage of material may be termed the Kastri group (pl. 9, 1–4).

These groups are discussed in greater detail in Appendix 2. The great bulk of the finds of the Keros-Syros culture, however, are from the cemeteries of Syros and Naxos, together with the objects from Dhaskalio in Keros. The notable homogeneity of the cemeteries at Chalandriani in Syros is indicated in table Appx. 2.1. Painted pottery (fig. 11.1, 9; pl. 7, 2–5), ‘frying pans’ of Syros type (fig. 11.1, 10; pl. 7, 1), ‘sauceboats’, folded-arm figurines, marble and metal objects, are found associated together in such a way that no internal grouping can be discovered. Thus, while the Kastri and Amorgos groups may be late in the duration of the Keros-Syros culture, in the Early Bronze 3 period of the Aegean, the bulk of the cemetery finds form a homogeneous assemblage principally of Early Bronze 2 date.

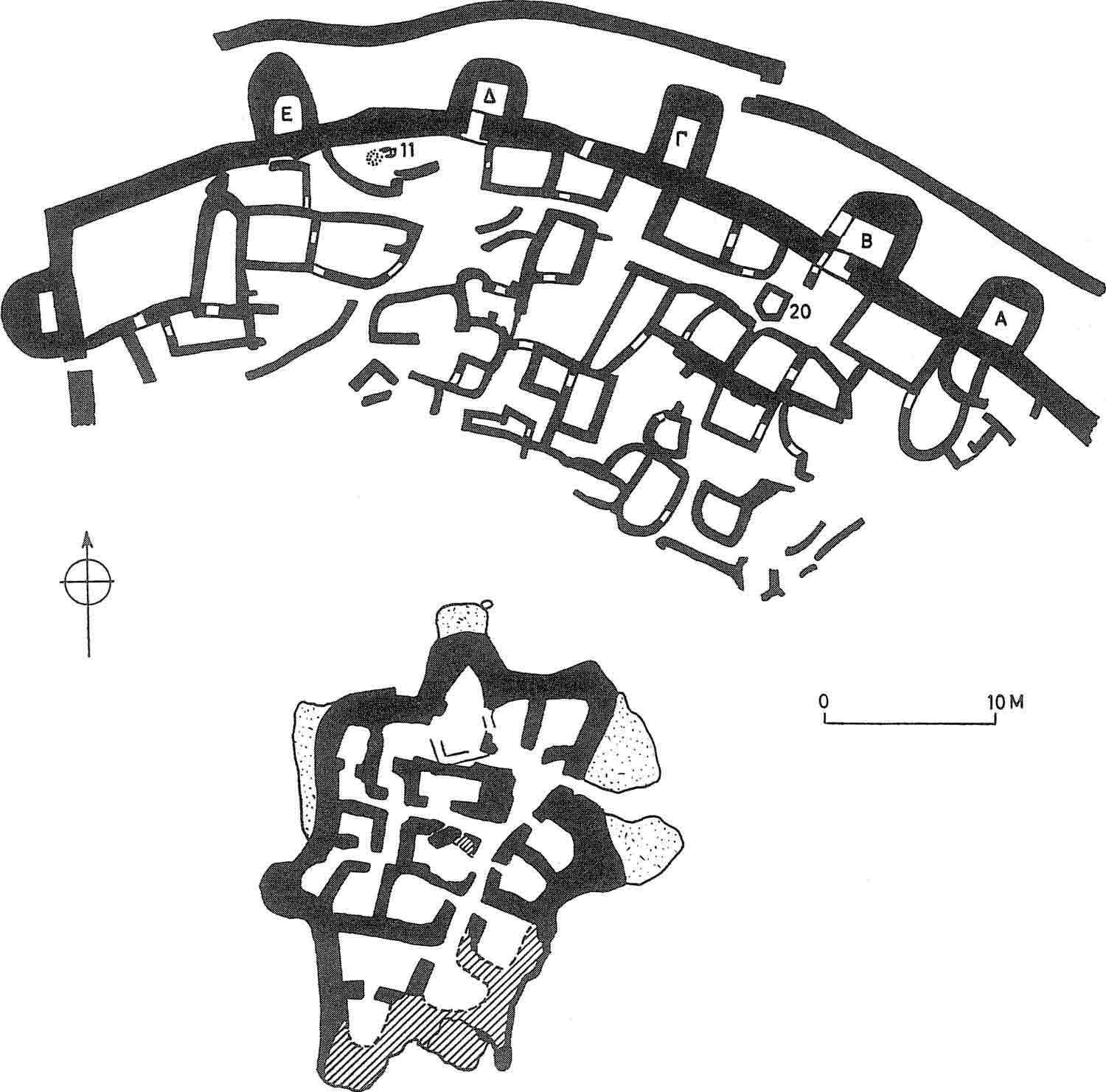

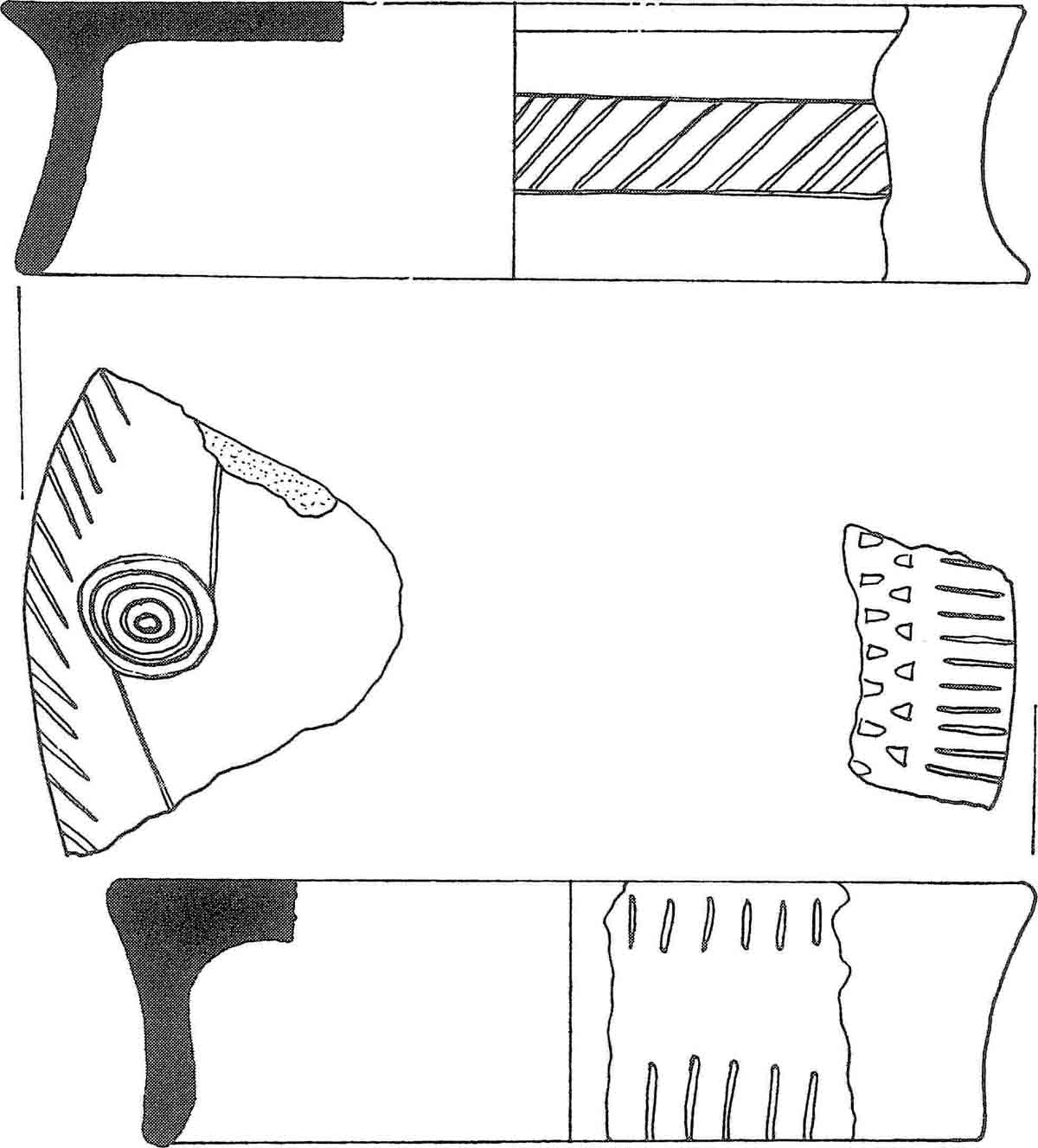

FIG. 11.2 Forms of the Kastri group of the Keros-Syros culture, from Kastri near Chalandriani on Syros (drawings after originals by Bossert). Scale 2:5.

The folded-arm figurine (figs. 19.5 and 19.6) deserves special mention here in view of its chronological importance. Some seventeen examples have been found in the Cyclades with well associated material (generally in the same grave) which can independently be dated. In every case, and without exception, the associations are of the Keros-Syros culture (Renfrew 1969a, 11 f.) The associations in the Spedos cemetery in Naxos (Graves 10 and 12; Papathanasopoulos 1961–2, pl. 46 and 53), at Chalandriani in Syros (Graves 307, 345 and 447; Tsountas 1899,111), and at Dokathismata in Amorgos (Graves 13 and 14; Tsountas 1898,154), are especially significant.

In addition there are eight folded-arm figurines from Chalandriani in Syros whose associations are not recorded, but which, in view of the other finds there, are clearly of the Keros-Syros culture. The same holds true for the numerous fragments and the single complete example from Dhaskalio in Keros (Zapheiropoulou 1968b, 97).

In all the cases in Syros and Naxos, where the associations are preserved, they are of normal Keros-Syros type, and not referable to the Kastri group of that culture. Some of those in Amorgos must be associated with the Amorgos group, and it seems likely that they were manufactured in the Early Bronze 3 period as well as in Early Bronze 2.

Mention should be made also of the finds at Aghia Irini in Kea and at Phylakopi in Melos (Renfrew 1969a, 24), where the figurines are not, however, well stratified. This occurrence on Melos, and also on Antiparos and los, is of interest since other finds of the culture are not recorded from these islands. Perhaps further finds remain to be made there, or alternatively, the folded-arm figurines of Melos may be imports like those found in mainland Greece.

The folded-arm figurine type has been divided into several distinct varieties (Renfrew 1969a, 15 f.), whose artistic and social implications will be considered later. They are illustrated in figs. 19.5 and 19.6 and pls. 30–32, and the distribution in Crete and the Cyclades shown on fig. 19.7 (mainland finds on fig. 20.5). The Kapsala variety, with its rounded form, the Dokathismata variety with its stylish elongation and the squat Chalandriani variety are particularly well defined. The Spedos variety is something of a residual category, with greater range in shape. Here it is important to note that the flat Koumasa variety is restricted entirely to Crete and was almost certainly manufactured there. Seventeen examples of this variety are known from Crete as against twelve entire or fragmentary examples of other varieties of the folded-arm type, which were presumably imported. The Cretan examples are probably all from Early Minoan II or Early Minoan III contexts, although the precise associations are not always clear. About fourteen folded-arm figurines are known from southern Greece, all probably imports. None is documented from western Anatolia, although Bent (1888, 82) wrote of a find at Kap Krio near Knidos.

FIG. 11.3 Metal types from the Chalandriani cemetery on Syros (after Tsountas). Scale 2:3.

These beautiful and remarkable objects will be considered again in a later chapter. For the moment it is sufficient to appreciate their integral position in the material assemblage of the Keros-Syros culture. Although these figurines have at times been viewed as products of the Early Cycladic cultures in general, they can in fact be recognised as one of the typical and diagnostic forms of the Keros-Syros culture, achieving a wide distribution in the southern and western Aegean (fig. 20.5).

The foregoing discussion of the variations within the material goods of the culture has touched already on many of the principal sites. To the present time only four settlements have been substantially excavated, although several more are known. Their locations are given in the Gazetteer.

Chalandriani in Syros is best known from the extensive cemeteries excavated by Tsountas (1899). He also investigated the small fort at Kastri which has been reexcavated by Fischer-Bossert (1967). Kastri itself is at the summit of a small hill rising steeply from the sea to a height of nearly 170 m (fig. 14.15 and pl. 14, 1). To the south, east and west there are steep-sided ravines, and a fortification wall defends the small stronghold from attack from the seaward side to the north. The cemeteries lie some way to the south, on the other side of the ravine. And the principal settlement may have been to the west of these, as Tsountas suggested. Kastri would then be a stronghold and place of refuge rather than the principal and permanent settlement. Certainly sherds have been found in this area, which lies about one kilometre to the south-west of Kastri. In 1963 I was handed several sherds (now in the Syros museum) which had been found there by a farmer: they included a ‘sauceboat’ spout and part of one of the incised pyxides discussed in Appendix 2 (cf. fig. 11.2, 3). Excavation would be needed to determine whether or not there was a major settlement—perhaps even a town, as Tsountas suggested—at this spot.

Kastri at Chalandriani ranks as a major fortified site in the Cyclades, although it is less than 50 m in width (pl. 21, 1; fig. 11.4). The lower courses of the wall and parts of six semi-circular bastions are preserved. There are traces also of what may have been a second circuit wall four or five metres outside the first. But its significance is not clear. Entrance was through one of the towers, and there are two further apertures in the wall. All the walling at Chalandriani is of the drystone type: large blocks, like those seen in the fortifications at Phylakopi II (pl. 21, 3), were not used.

The interior plan is clear, consisting of small aggregates of rooms, generally only two or three metres in diameter, and separated by narrow paths or ‘streets’. In shape they are irregular, neither strictly rectilinear nor curvilinear. Hearths were found in three of these rooms, and in one of these, in Room 11, bronze slag was found in the ashes together with part of a crucible (Bossert 1967, fig. 3.5) and the important hoard of metal objects described in chapter 16. Further crucible fragments and stone moulds were also found on the site, as well as lumps of lead, together with other evidence of lead working. The pottery found at Kastri is discussed in Appendix 2. Other finds include two short daggers and a slotted spearhead.

A little fort found near Panormos in south-east Naxos is in some ways rather similar (Doumas 1964, 411). Situated at the summit of a low hill, Korphari ton Amygdalon, overlooking the bay of Panormos, is again accompanied by a cemetery. It may be simply the fortified stronghold of a larger settlement which Doumas, the excavator, believes lies nearby.

The fort is only 25 m long (fig. 11.4; pl. 21, 2) and consists of an enclosing wall with several irregular, roughly semicircular bastions. Entrance was by a gateway on the east side, outside of which a large heap of uniform-sized circular stones was found. These have been plausibly identified as sling stones for the use of the defenders. The rather limited space within is completely taken up by more than a dozen little rooms, each only a couple of metres wide, linked by narrow passageways. The finds were few, but place the settlement in the Keros-Syros culture. The most important was a spearhead with bent tang, but without slots (cf. Stronach 1957, fig. 4.1). Part of a marble bowl with four horizontal ledge lugs at the rim, a typical Keros-Syros type, was found on the surface (cf. Bossert 1967, fig. 5.4).

FIG. 11.4 Fortified stronghlods of the Keros-Syros culture: Kastri Chalandriani on Syros (above); Panormos on Naxos (below).

South-east of Panormos lie the Kouphonisia and the small island of Keros. The third excavated settlement of the culture is situated on a tiny islet, really little more than a rock, just off the west coast of Keros: Dhaskalio. It may well have been linked to Keros by a neck of land in the third millennium BC. On top of this islet were found the foundations of a rectangular building, presumably a house (Doumas 1964,410). The rich but fragmentary finds from what was probably a disturbed cemetery were made on Keros immediately facing Dhaskalio.

The fourth site, which has been unjustly neglected in some accounts, is at the summit of the Kynthos on the island of Delos (Plassart 1928, pl. III). Once again it is a hilltop settlement in a fine defensive position, at the summit of a rather steep hill, some 100 m high, overlooking a safe harbour, and with magnificent views in all directions. It may well have been fortified, but this is not clear since the site was much disturbed by Hellenistic constructions of the third century BC. The preserved walls resemble those of Chalandriani and Panormos, with closely juxtaposed, small rooms of irregular shape.

The finds include fragments of ‘sauceboat’s and of footed jars of typical Syros form. There are also part of incised spherical pyxides, and very lustrous, black, one-handled cups which are hallmarks of the Kastri group. The site is interesting also for the stone grinders and various objects of stone and clay for domestic use. Such finds seem to have been lacking at Kastri and Panormos, confirming their status as places of refuge.

Finally mention should be made of the interesting site at Korphi t’Aroniou in southeast Naxos. The dating evidence for this small site is not rich, but probably it falls within the time span of the Keros-Syros culture. Its great importance lies in the carved stones found there, worked by a pecking technique, which show scenes of uncertain interpretation, including apparently dancing and perhaps ploughing (Doumas 1965). Other carved stones are known from south-east Naxos (pl. 26, 1; Bardanis 1966).

In the central Cyclades, especially Naxos and Siphnos, many of the Grotta-Pelos cemeteries continued in use, with little change in the burial custom.

The size of the cemeteries did increase. For instance Stephanos excavated 170 graves at Aphendika (although it is not excluded that some may have been of Grotta-Pelos date), while Phyrroges had 120 and Karvounolakkoi 82 (including both Keros-Syros and Grotta-Pelos graves), without counting graves more recently opened. As we shall see, the Chalandriani cemetery contained more than 500. The Keros-Syros graves in Amorgos are very similar, although they seem to lie in much smaller groups, 20 graves reported at both Kapros and Dokathismata being the largest number recorded.

The burial customs, apart from the change in grave goods, apparently continued with little alteration. Double graves are still found in Siphnos at this time. Cist grave cemeteries of this kind are known from Naxos, Siphnos, Amorgos, Keros and the neighbouring isles, Thera (apparently) and Ios (probably), and there are Keros-Syros finds from Dhespotikon and Antiparos, which may have come from graves of this kind. Of the islands with Grotta-Pelos cist cemeteries, only Paros and Melos apparently lack burials of the Keros-Syros culture.

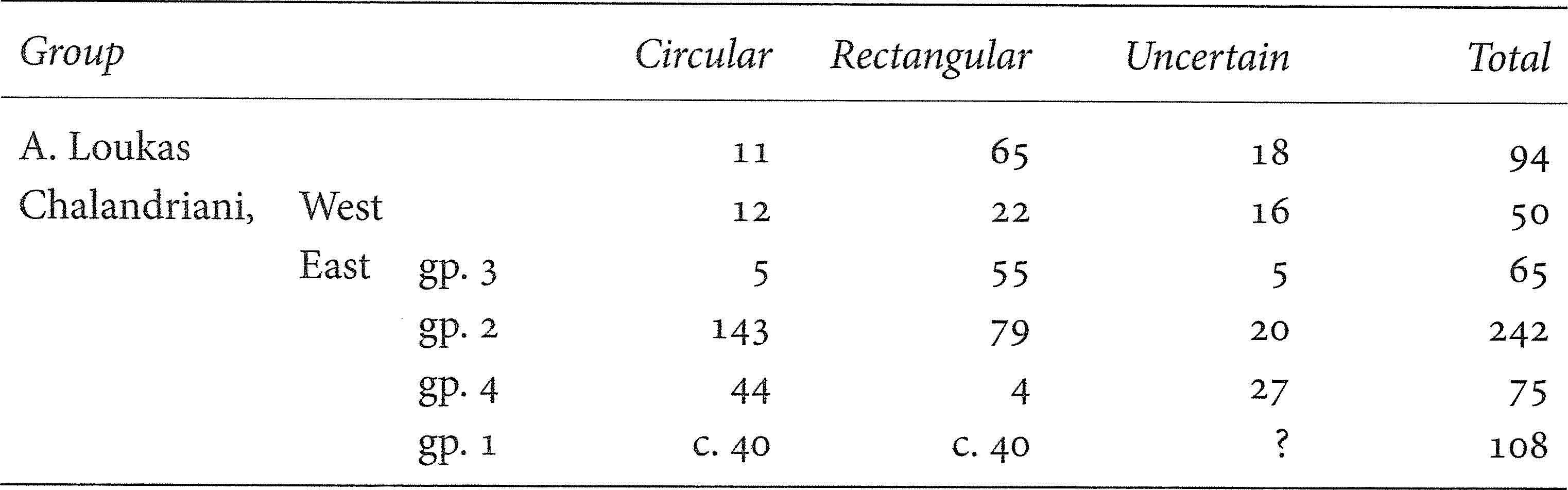

The cemetery at Chalandriani is different from these. It lay in two distinct areas: Tsountas excavated 50 graves in the western one, estimating those previously opened at about 100. The graves lay clustered in small groups. The eastern area contained four clusters of respectively 108,242,65 and 75 graves, giving a total of 490. At Aghios Loukas on Syros the cemetery comprised 94 graves.

Tsountas classed the graves as rectangular or circular (although some were intermediate). All were constructed entirely of drystone walling, unlike the cist graves just discussed which were built of upright slabs. The chamber was about 1.5 m wide, and each had a false entrance, closed with rough stones. Since each contained only a single burial (in only 10 cases were two or more burials found) this entrance had no obvious function. The drystone walls were surmounted by a slab in tholos fashion (cf. pl. 25, 2).

Tombs of similar form have been found at Lionas in Naxos (Doumas 1963, 279); and at Akrotiraki in Siphnos the graves were built of small stones, but without an entrance. The grave at Dhiakophtis on Mykonos may also have been of Syros type.

In each small group at Chalandriani the graves were predominantly circular or quadrangular, as shown in table 11.1.

TABLE 11.1 Grave types at Aghios Loukas and Chalandriani.

The knees of the dead man were drawn up to the waist, and he was laid on one side, generally on the left. The grave goods were placed at the head or at the feet.

In general the graves were poor. The commonest grave object was the small and simple pottery bowl (Type 40) of which examples were found in 224 graves; 129 simple cups were found in 121 graves. Other objects were less frequent, so that many of the graves seem to have been entirely without grave goods. The contents of the 32 richest graves were listed by Tsountas and are summarised in table Appendix 2.1 (cf. p. XXX).

The burial practices of the Keros-Syros culture in general closely resemble those of the Grotta-Pelos culture, although the cemeteries were larger. Within the Keros-Syros culture, however, the graves of Syros (together with Lionas etc.) must be singled out for their drystone construction and distinctive shape. They differ from the Grotta-Pelos graves in containing a single burial, with exceedingly few exceptions. These graves find precursors, as concerns the drystone walling, in the round and rectangular graves of Kephala in Kea, although these were without entrances except for one possible occurrence. And the Kephala graves generally contained several burials.

The affinities of the Keros-Syros culture are so numerous at this time, and the evidence for Aegean contacts so abundant that rather than listing the various forms of the culture individually it may be permissible to present the overall picture directly.

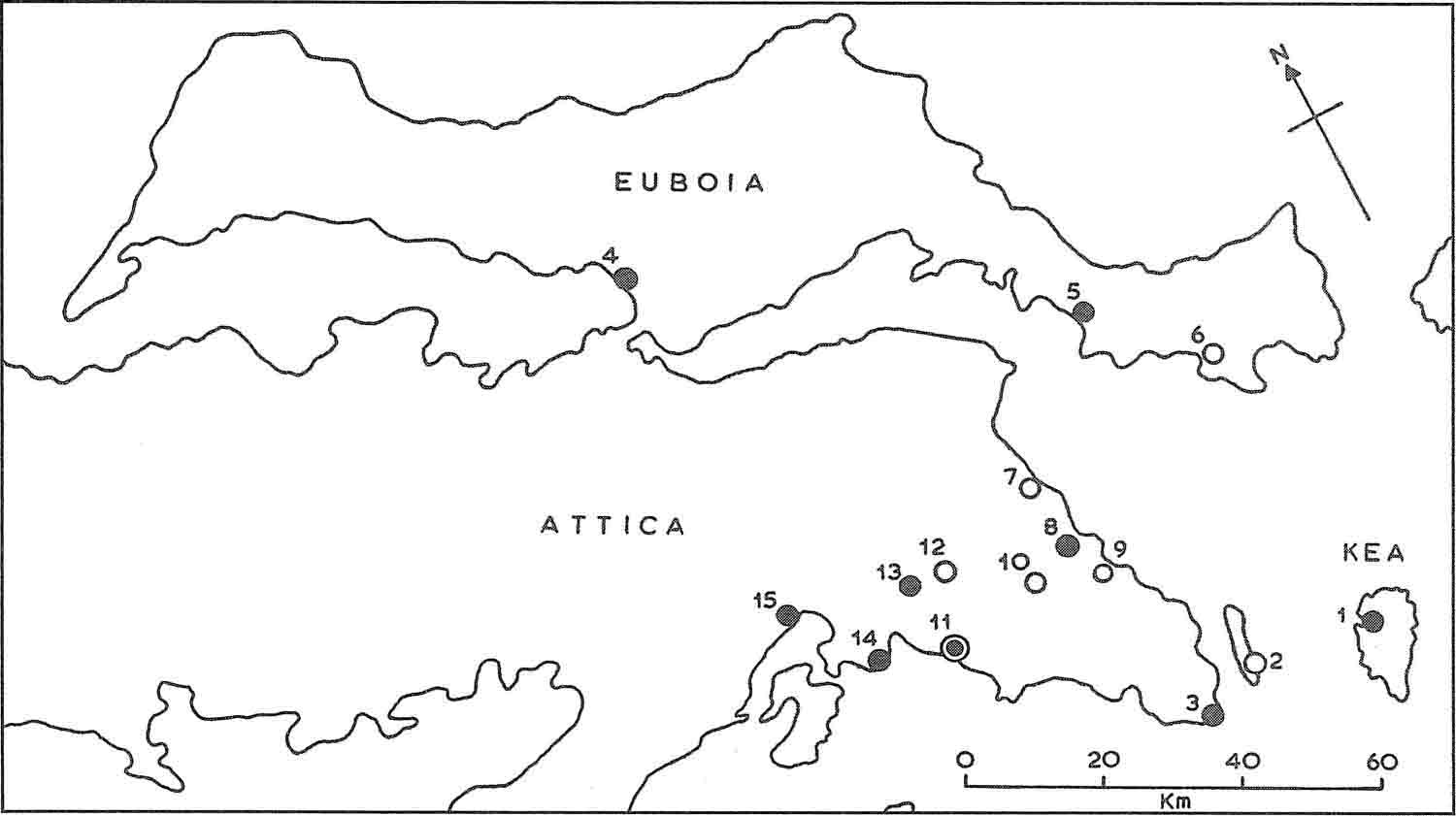

FIG. 11.5 The Attic-Cycladic Mischkultur: finds of Cyciadic type in Euboia and Attica. Dots represent findspots of folded-arm figurines, circles indicate cist graves containing other marble forms.

1, Aghia Irini; 2, Makronisi; 3, Sounion; 4, Manika; 5, Styra; 6, Makrykapa; 7, Raphina; 8, Brauron; 9, Porto Raphti; 10, Markopoulos; 11, Aghios Kosmas; 12, Chalandri; 13, Athens; 14, Piraeus; 15, Eleusis.

The chronological position of the culture is well attested. In Crete all its affinities are with Early Minoan II, as will be argued in chapter 13. On the mainland they are entirely with the Korakou culture, for the stamped wares of the Eutresis culture, although curiously similar, do not fall within the range of Keros-Syros types. And the late Kastri Group of the Keros-Syros culture has close affinities with the Lefkandi assemblage of the mainland, which succeeds the Korakou culture and precedes (or runs contemporary with) the Tiryns culture. Hie relations between the Cyclades and mainland Greece in the third millennium BC are further discussed in Appendix 2 in the section on the Attic-Cycladic Mischkultur. The patterned wares of the Lerna culture, so abundant in Lerna IV, have little in common with the Keros-Syros ones which are to be equated rather with Lerna III (Caskey 1960a). In west Anatolia the most numerous affinities of the Keros-Syros culture are with Troy II: the triple spouted sauceboat of Syros (Zervos 1957, pl. 185) may be compared with the two spouted version of gold from Treasure A at Troy (Schmidt 1902, 5863), and the double-spiral-headed pins form another link between Troy and the other Aegean cultures (fig. 11.3 and fig. 16.7). Aegean contacts, in the form of Korakou or Keros-Syros ‘sauceboat’ fragments begin in Troy I, however (Biegen et al. 1950,154), so that Troy II may begin later than these cultures. Equally some of the forms seen in the Cyclades and the mainland such as the one-handled cup (form A33 and 39 at Troy) and the depas (form A45) continue until phase V there. The Urfirnis depas is limited at Troy to phases II and III (Blegen et al 1950, 252) but as discussed in Appendix 2, the Kastri group has explicit parallels with Troy III and IV. It is probably safe enough to equate the Keros-Syros culture with late Troy I, Troy II and perhaps early Troy III (while allowing the Kastri and Amorgos Groups to last into the Troy IV period). When referring to the time when all these cultures were flourishing, it is convenient to speak of the Early Bronze 2 period. But since Troy II, Early Minoan II, and the Korakou and Keros-Syros cultures are certainly not coterminous, this convenient term should not be given too precise a meaning.

FIG. 11.6 The mainland ‘frying pan’. (Above) lid from Lerna III (L.1448); (below) lid or pan from Corinth (I.B1). Scale 1:2.

FIG. 11.7 Findspots of ‘frying pans’, and pottery decorated with stamped circles, in the Cyclades and south Greece.

Upright triangles denote findspots of ‘frying pans’ of Kampos type; squares, those of Syros type; circles, those of mainland type; inverted triangles, other ‘frying pans’; crosses, findspots of other sherds decorated with stamped circles.

1, Kampos; 2, Grotta; 3, Kato Akrotiri; 4, ‘Sikinos’; 5, Manika; 6, Chalandriani; 7, Dhiakophtis; 8, south-east Naxos; 9, Akrotiraki (doubtful); 10, Raphina; 11,‘Andros’; 12, Aghios Kosmas; 13, Palaia Kokkinia; 14, Aegina; 15, Corinth; 16, Lerna; 17, Phylakopi; 18, Pyrgos; 19, Eutresis; 20, Athens; 21, Askitario; 22, Korakou; 23, Zygouries; 24, Asine; 25, Asea.

The number of cultural links seen at this time in the Aegean is quite remarkable. The one-handled cup, for example (fig. 20.4), suddenly becomes a widespread form, where previously links of this kind between any two local regions in the Aegean were unusual, and between all of them totally unknown. Nor does anyone region dominate the others to a preponderant extent. Certainly a high proportion of the forms, such as the depas (fig. 11.2, 4), are of Anatolian origin, but the ‘sauceboat’, usually considered a Helladic type, has an equally wide distribution. And the Cycladic folded-arm figurine is widely found in the mainland as well as in Crete which otherwise seems to hold rather aloof from the Aegean world during the early bronze age.

It is this international flavour, a widespread distribution of forms with different origins, which leads one to think of a continuum rather than of cultural influence emanating from a single source. The explanation of this sudden burst of trading activity must surely lie in the new demand for metal, and in its satisfaction. It is only now in each of these regions that metallurgy takes on any importance, and indeed there is little enough evidence that it was practised at all in the preceding Early Bronze I period, except at Troy. This question is discussed again in chapter 20.

The Keros-Syros culture cannot usefully be regarded as the product of some foreign inroad. Certainly many of the forms are Anatolian, but, as seen in the last section, the movement is not all one way. Indeed even among the metal forms some may be of local origin: the knot-headed pin perhaps (Tsountas 1899, pl. 10, 18 and 21), the tangless slotted spearhead (Stronach 1957,103) and even the tweezers so frequent in Syros (fig. 11.3) and seen in Manika, Aghios Kosmas, Zygouries and in Crete are later in date in the Near East than in the Aegean (Deshayes 1960, 163). Yet while a direct Anatolian origin cannot be countenanced—as it may be for the Kastri Group, for the Manika tombs, and for the Lefkandi assemblage—there must have been very considerable west Anatolian influence.

Of the many striking features possessed by the Keros-Syros culture, some may be linked with the mainland. The construction of fortifications with round bastions at Chalandriani and Panormos, not seen at Troy or Poliochni, finds a very close parallel at Lerna III. And, as mentioned in chapter 7, the use of stamped circles and spirals is attested on the mainland in earlier contexts than any yet known in Syros (cf. Fig. 11.6 and 11.7).

FIG. 11.8 The evolutionary development of the Early Cycladic figurines.

The precursors of the Keros-Syros culture remain vague. It seems to owe surprisingly little to the Grotta-Pelos culture, although the footed vessels (pl 8, 10–11) could be a development of the Pelos form (pl. 3, 5), and the marble dish with rolled rim of Syros must surely originate in the Grotta bowls. The tomb form, however, is really very close to that of Kephala, which is very much earlier. Now there can be no question of the remarkable cultural unity of the Chalandriani graves and their contents springing fully-fledged into the world, and one is led to suggest the existence of an earlier and as yet undocumented phase of the Keros-Syros culture.

This hypothesis, propter necessitatem, not only allows for a continuity in the construction of built tombs like those of Kephala, but gets over the considerable chronological difficulty presented by the mainland stamped wares. These certainly occur in the Eutresis culture, and either we must derive the Syros ones from them, which seems odd, or admit the existence in the Cyclades of a prototype for the Syros decorated wares, to which the mainland ones could be related.

This would conveniently allow for a development of the folded-arm figurine of marble from the prototype in clay seen in the Attic-Kephala culture, and indeed for the repertoire of stone vessels. Whether the patterned ware and the ‘sauceboat’ have an ultimately Cycladic or Helladic origin remains to be seen. But the presence of a little painted cup resembling those of the Cyclades in the Pyrgos burial deposit in Crete (Xanthoudides 1918,145, fig. 6.22) and the wider range of painted ‘sauceboats’ seen in Keros than anywhere else in the Aegean, taken together with the footed marble ‘sauceboat’ known from the Cyclades, at least suggest that the former is a possibility.

But whatever the ultimate origins of the various forms and traits which constitute the culture, there can be no doubt that its great wealth and variety was due in large measure to the same underlying causes as produced the House of the Tiles at Lerna or the magnificent treasures of Troy and Alaca Hüyük.