The preceding chapters, of Part I, have established the culture sequence in the various regions of the Aegean during the third millennium BC. This was a crucial period, as reviewed in Chapter 4, for the evolution of Aegean civilisation. The task now, in Part II of the present work, is to gain some insight into how and why these various developments occurred.

The model presented in Chapters 1 to 3 is useful here. The third millennium Aegean is divided into cultures, each with its own territory—Crete, Cyclades, south Greece, etc. Each culture may be regarded as a system whose units are the persons, artefacts and elements of the environment, related by the activities of the members of the culture. The different fields of action―subsistence, technology, social, projective―define the subsystems. In succeeding chapters each of these subsystems will be considered in turn, the subsistence subsystem of all the regions in one chapter, the social subsystems in another, and so forth.

In terms of this model, the human population of the Aegean does not constitute a subsystem in itself. It is a parameter, a relevant statistic of all the subsystems. Obviously it reflects the absolute size of the culture systems in terms of individuals, and population density influences all the subsystems of the culture. But the population itself does not define for us the different patterns of activity in the various fields or dimensions of human existence. And it is these activities in the different fields which determine the nature of the subsystems.

The settlement pattern, likewise, while itself a fundamental aspect of the culture, is not in this sense a system or a subsystem. It documents where and how the various activities are carried out: it is a symptom.

Precisely because population is a fundamental parameter of all the subsystems which constitute a society, and settlement pattern an obvious record and symptom of so many activities, their study must form the starting point for any investigation of a prehistoric culture or society. They are considered here as a preliminary to the discussion of the various subsystems, undertaken in succeeding chapters.

Settlement patterning obviously constitutes a major source of information for prehistorians. Yet despite the use which archaeologists have long made of distribution maps, and their growing awareness of environmental factors, a consideration in quantitative terms is still a rarity.

The limitations imposed by the material are obvious, and in the past have doubtless inhibited quantitative considerations. Several factors must be borne in mind (Renfrew 1971) including the destruction of and failure to recognise certain classes of site, and the varying intensity of archaeological research in different areas.

Locational analysis applied to prehistoric material differs from applications to recent material first by the various uncertainties in the relationship between the original or ‘true’ population at a given time, and the sample in hand. Secondly the analysis is generally diachronic, it has time depth―sometimes confusingly so, since there is no guarantee that sites of a given period or culture, even permanent habitation sites, were in fact occupied at the same time.

Despite these limitations, order of magnitude comparisons of some plausibility can be made, sometimes on a quantitative basis. In general a comparison of the data between the periods or areas may reduce rather than increase the errors. For the uncertainties discussed are not random ones, and the factors governing preservation and detection for the different sites are correlated, and may continue to hold for different regions or different time periods.

Several aspects of prehistoric settlement in the Aegean will be considered in turn:

1. Settlement density in the different regions of the Aegean.

2. Patterns of settlement increase in selected regions.

3. Development of settlement size from the neolithic to the late bronze age.

4. Continuity and discontinuity of settlement occupation.

5. Population density and size in the various regions.

6. Settlement location and settlement hierarchy.

Recent systematic and intensive site surveys in different regions have made the Aegean one of the most comprehensively surveyed areas in the world. No evaluation of the results has yet been undertaken, perhaps because all those who have themselves surveyed the sites know how very incomplete and haphazard is the picture we now have of the prehistoric settlement pattern. And yet, although an attempted analysis may seem premature, certain broad, order-of-magnitude results emerge. They suggest, in turn, further lines of approach.

Remains of the neolithic period in Greece were first intensively investigated in Thessaly. The maghoulas (tell mounds) there were clearly prosperous and long-lived settlements in the neolithic period. The work of Tsountas (1908) and of Wace and Thompson (1912) was followed by comparable studies in Macedonia (Heurtley 1939). And although neolithic sites are known in plenty in southern Greece and in Crete and more sparingly in the islands and west Anatolia, only rarely―at Knossos or Hagiorgitika―do they achieve there a sufficient depth of deposit to be considered tells.

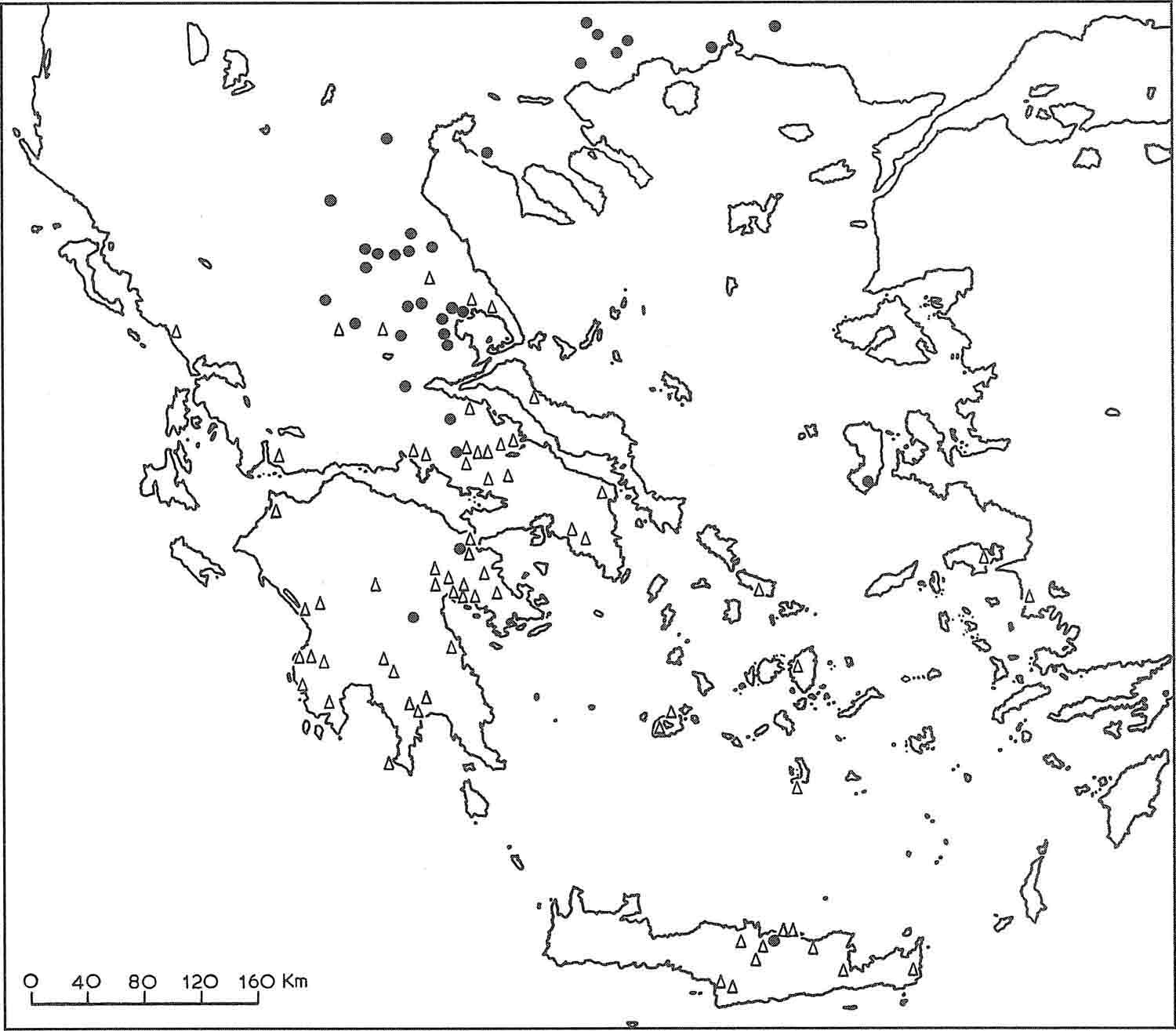

At first sight this might suggest that the fertile plains of Thessaly and Macedonia were more intensively settled than southern Greece, and the sites occupied for longer periods. This is not necessarily so, since tell formation depends as much on the use of mud brick or pisé in construction as on prolonged occupation. Stone materials were easier to re-use, and the rate of deposition in stone-built settlements consequently much slower. None the less, the depth of deposit of neolithic levels on open sites (hence excluding caves) seems a meaningful criterion for long-lived permanent habitation sites of this particular type. Fig. 14.1 shows the distribution of open sites in the Aegean where more than 2 m of neolithic deposits have been found. Except in a few cases (Dhimitra, Megalokambos) this information is available only for excavated sites, so that the distribution is in part a reflection of recent archaeological activity and not solely of prehistoric settlement density. The map may contain some errors, and certainly some omissions, and does not pretend to reflect settlement density at a given point in time. Despite these limitations, it clearly indicates that neolithic tell settlement in the Aegean is most densely concentrated in the fertile plains of Thessaly and Macedonia. This conclusion is in conformity with the distribution of tell settlement in south-eastern Europe as a whole: tells are generally restricted to fertile lowland plains.

Contrasting markedly with the distribution of neolithic tell settlements is that of the Mycenaean and Minoan settlements of the late bronze age, which is dense in southern Greece and the islands and very sparse in the north. To plot the totality of known Minoan and Mycenaean sites of the late bronze age would be misleading, since this would exclude much of northern Greece, where there is plenty of evidence for late bronze age occupation, but only sparse indications of Mycenaean activity. Our interest here, however, is the emergence of civilisation, and there is no doubt that the distribution of such ‘civilised’ features as palaces, built stone tombs, and stone fortification walls is a southerly one. Fig. 14.1 therefore shows the Aegean late bronze age distribution of palaces, villas, megarons and fortified strongholds, following Hope Simpson (1965) and Graham (1962), with a few additions.

This map again makes no claim to be complete, but despite omissions a very clear picture emerges. Aegean civilisation was a feature of the southern Aegean, especially Crete and the Peloponnese, although it extended north as far as Thessaly, east to the Dodecanese, and to Kephallenia in the west. A similar definition of the extent of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation is yielded by the distribution of late bronze age tholos tombs (fig. 4.2). The settlement in Macedonia and Thrace, although indeed fairly dense in the late bronze age, may not have differed significantly in type from that of the late neolithic period. Recent work in the Plain of Drama in Macedonia does, however, indicate a shift there in the later bronze age from tell settlement to the occupation of defensible sites on low hills, of which at least one was fortified. So far this observation has not been repeated in other areas of north Greece, but it suggests caution in making too sharp a distinction between north and south Greece in the later bronze age.

This general pattern can already be seen in embryo during the early bronze age. Stone fortifications became widespread at this time, although seen first during the neolithic at Dhimini in the then flourishing Thessalian region. And while there are no palaces and few impressive built tombs in the early bronze age, the development of cemeteries, and of burial techniques beyond that of simple inhumation in the soil (the burials often accompanied with rich grave goods) heralds the more monumental features of late bronze age funerary custom. Fig. 18.12 shows the known stone-fortified sites of the Aegean early bronze age, together with the principal cemetery sites. Some of the Cycladic cemeteries (which are seen in full on fig. Appx. 1.2) are omitted for convenience, and the representation of Yortan cemeteries in north-west Anatolia is not complete. Cave burials in Crete are omitted.

FIG. 14.1 The contrasting distribution of neolithic tell mounds and of major late bronze age sites in the Aegean. The late bronze age sites comprise all those listed by Hope Simpson (1965, 195) under the headings palaces, megara, fortresses, together with those classed by Graham (1962) as palaces or villas (with the addition of Zakros in Crete, Akrotiri in Thera and Akroterion Gurion in Tenos). The neolithic tell mounds are those which have yielded more than two metres of stratified deposit; many unexcavated mounds are therefore excluded (see notes to the figures).

These three maps say nothing of intensity or size of settlement. They do indicate how a new distribution of a different kind emerged during the early bronze age and was consolidated during the late bronze age. The stability of this configuration is documented by its persistence to the early ‘archaic’ period of the classical Greek civilisation.

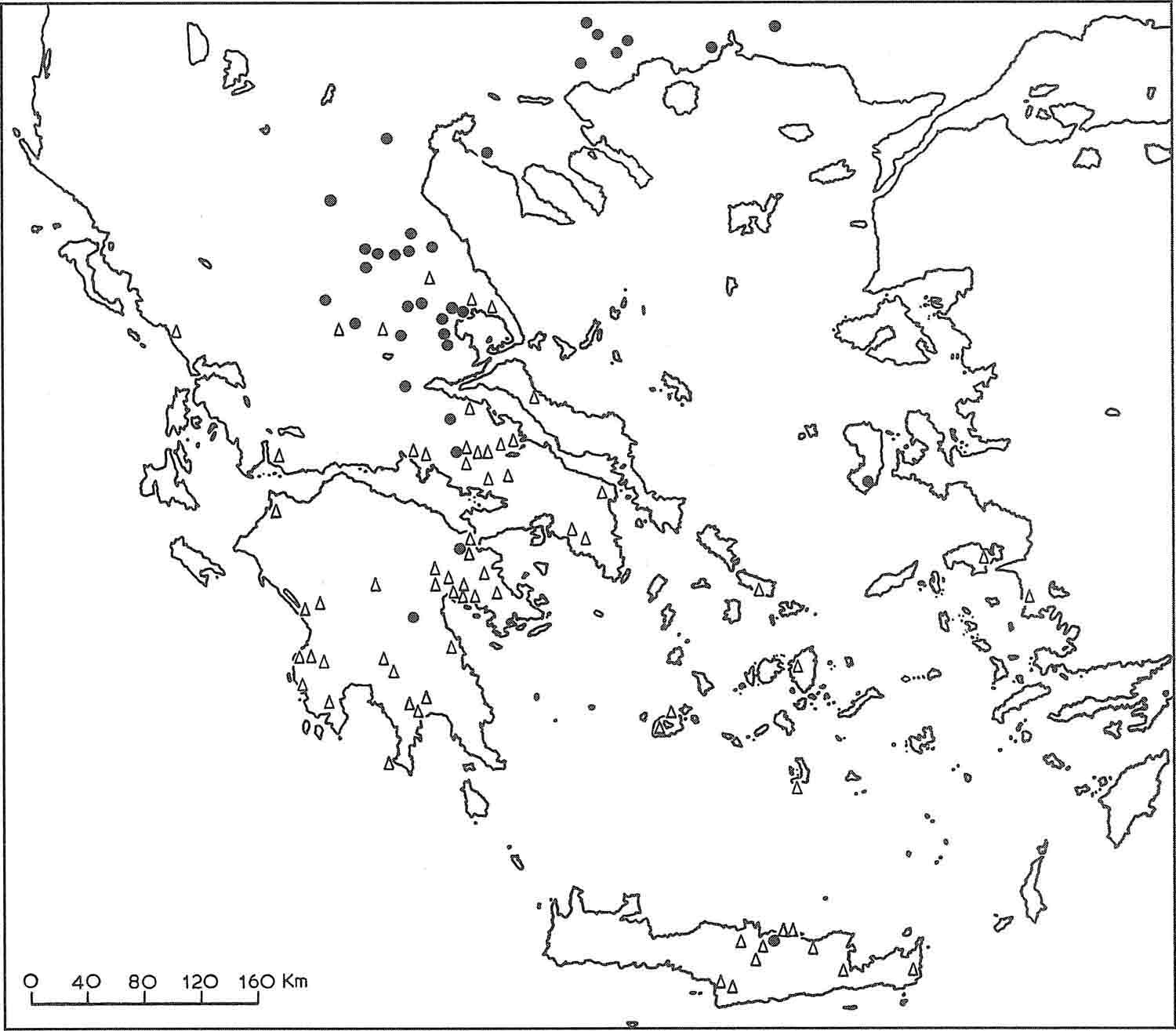

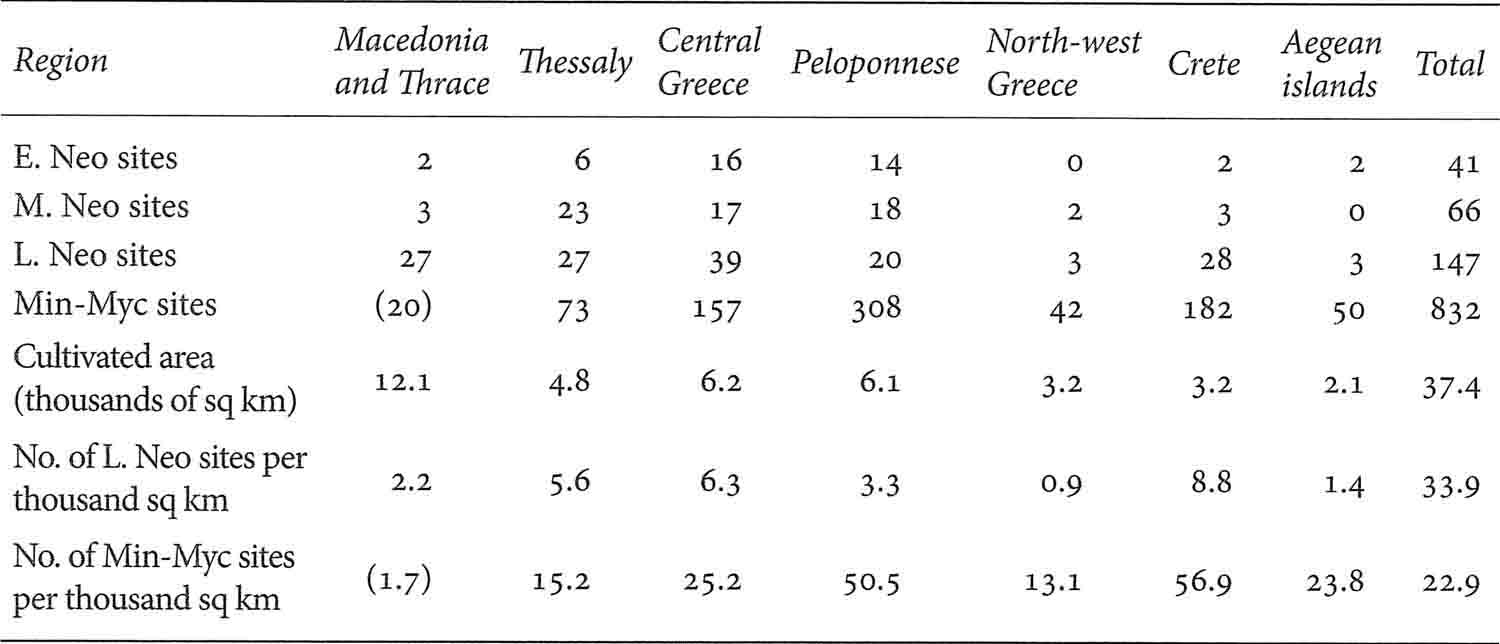

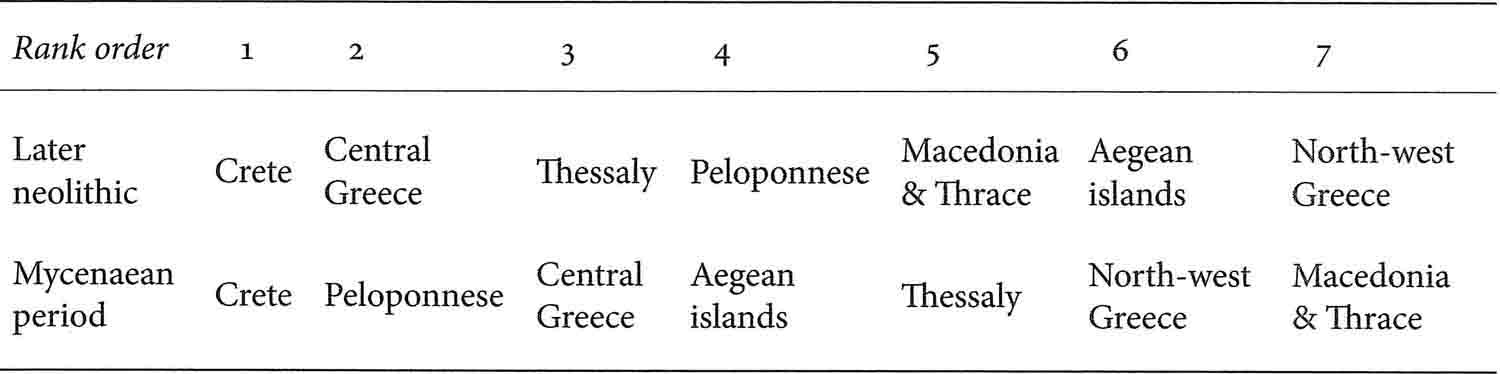

These are distributions by settlement type―tells as against palaces, cemeteries and so forth. They do not yield information about the density of settlement in different regions. An approach to this question, although a very inadequate one of uncertain validity, is to consider the distribution maps given by Weinberg (1965a) for his three periods of neolithic settlement in Greece (the late neolithic including also the final neolithic as defined here in Chapter 5). Weinberg’s maps give an excellent picture of current knowledge, but inevitably a figure for the density of settlement reflects first the intensity of the search. A count of the neolithic settlements shown on these maps for the different regions of Greece is given in Table 14.1.

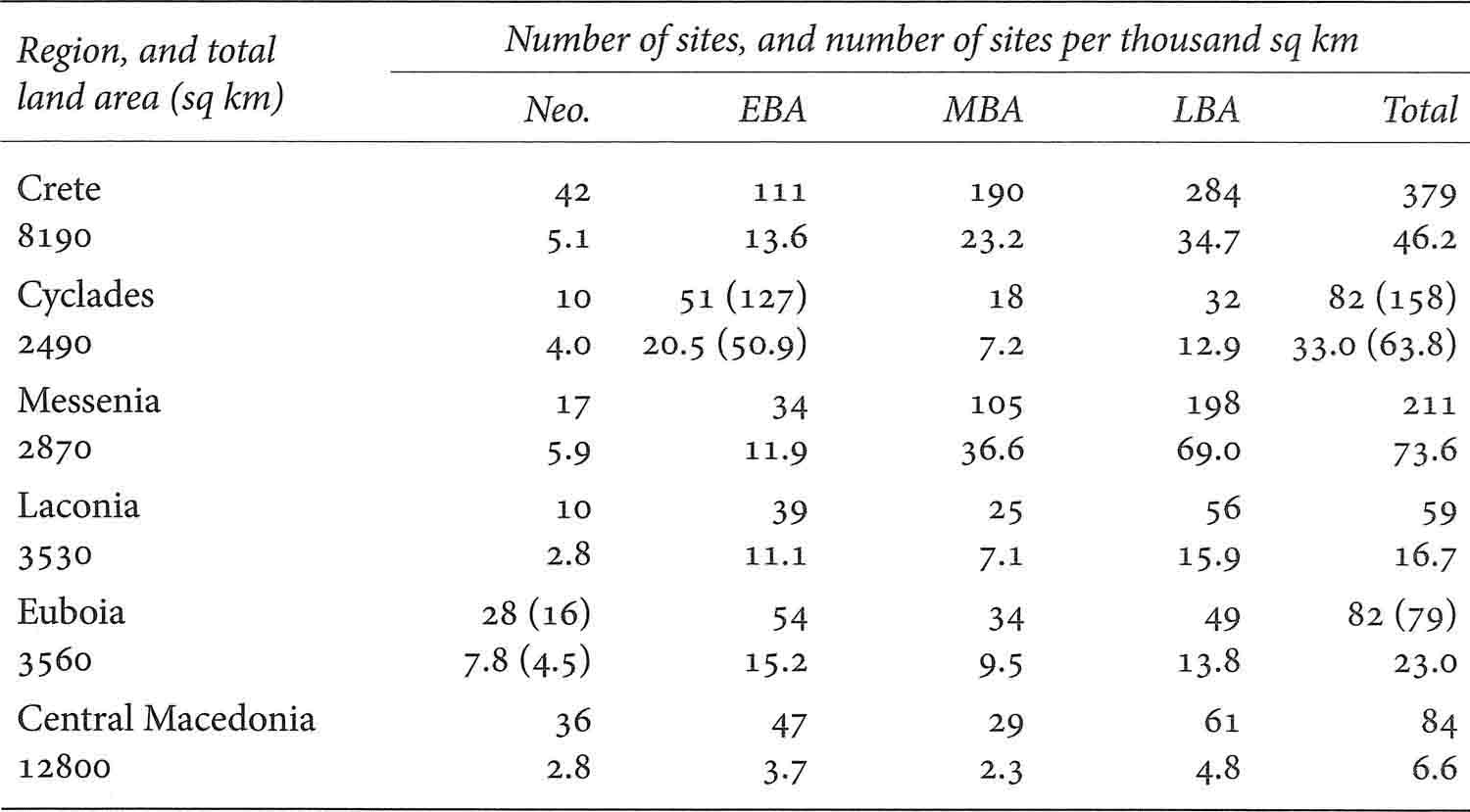

TABLE 14.1 The apparent density of settlement of neolithic and Minoan-Mycenaean sites in the different regions of Greece, calculated on the basis of recent surveys. (The figures are not, however, strictly comparable, in view of the different intensity of survey in the different regions.)

For the purposes of crude comparison a similar count of Minoan and Mycenaean sites is given, compiled from the lists of Hope Simpson (1965) and from Pendlebury’s map (1939, 284). The figure for Macedonia and Thrace is artificially low for the late bronze age, since sites in this area lack Mycenaean remains. Figures for the area of land cultivated in each region in 1961 (Ethniki Statistiki Yperesseia 1962a) allow the approximate comparison of the observed settlement densities. (North-west Greece here comprises the Ionian islands, Aetolia, Acarnania and Epirus; central Greece here includes Attica and Euboia.)

These figures possibly reflect as much as anything the intensity of survey work in prehistoric Crete. Crete remains, indeed, the only one of these regions for which a comprehensive survey has been published. French’s recent survey in central Macedonia (1967a), which has in a single stroke increased the number of known sites by more than 50 per cent, documents the great extent to which these figures reflect the intensity of archaeological exploration.

TABLE 14.2 The various regions of Greece arranged in rank order in terms of observed settlement density, for later neolithic and Minoan-Mycenaean sites.

None the less it is worth contrasting the rank order of regions in terms of the observed settlement densities, for the later neolithic and for Minoan-Mycenaean settlements.

Crete retains its pre-eminence. Central Greece, Thessaly and Macedonia and Thrace decline in rank order over the period in question. On the other hand the Peloponnese, the Aegean Islands and north-west Greece go up in rank order.

However unreliable these results may be, established as they are on the basis of observed settlement density, they certainly correlate rather well with those obtained above for settlement type. It is precisely those regions where tell settlement is most notable in the neolithic period which have declined in relative importance by the late bronze age. The tell distribution is seen on figs. 14.1 and 15.2; the relevant geographical areas are named in fig. 20.5.

The contrast between the various regions are further discussed in the next section, and correlated with the vegetation zones in the next chapter.

Comparisons of settlement density for several areas are much more difficult than comparisons of settlement size or even of settlement type. For the number of sites recovered is very closely proportional to the intensity of survey, while the size of sites and even the variety in type of site should emerge gradually as exploration proceeds. For that reason the settlement densities expressed in Table 14.1 can have little real meaning: they represent the state of our knowledge rather than of prehistoric settlement.

On the other hand, within a given region, the period-by-period comparison of the density of known sites should be far less dependent upon the intensity of exploration. Since site surveys normally yield material of all prehistoric periods, a biased search for sites of one period will none the less yield sites of all cultural phases. The principal bias here is introduced when different types of site were occupied preferentially in different periods. Tells and acropolis sites, for instance, are notoriously easy to discover, and in consequence most surveys will favour the periods when they were occupied. And again, in the Cyclades the early bronze age practice of burial in cist graves undoubtedly ensures that a high proportion of the prehistoric cemeteries originally utilised are in fact recovered (just as tumuli and kurgans make obvious the cemeteries of central and northern Europe). Periods when such burial customs are in operation are thus disproportionately favoured.

None the less, the most appropriate procedure for the comparison of settlement densities would seem to be the period-by-period comparison of occupations within designated areas. We can then primarily compare not the absolute densities of settlement in the various regions but rather the patterns of change which are revealed in the different regions.

It should be noted, of course, that sites may not have been occupied throughout the length of the specific period divisions used (neolithic, middle bronze age, etc.). The settlement density as given by the totality of recorded sites occupied during the period thus yields a maximum figure. The relative length of the periods is clearly also a factor here, since a high score of recorded settlements during a short period division (such as the middle bronze age) is more remarkable than over a longer time span.

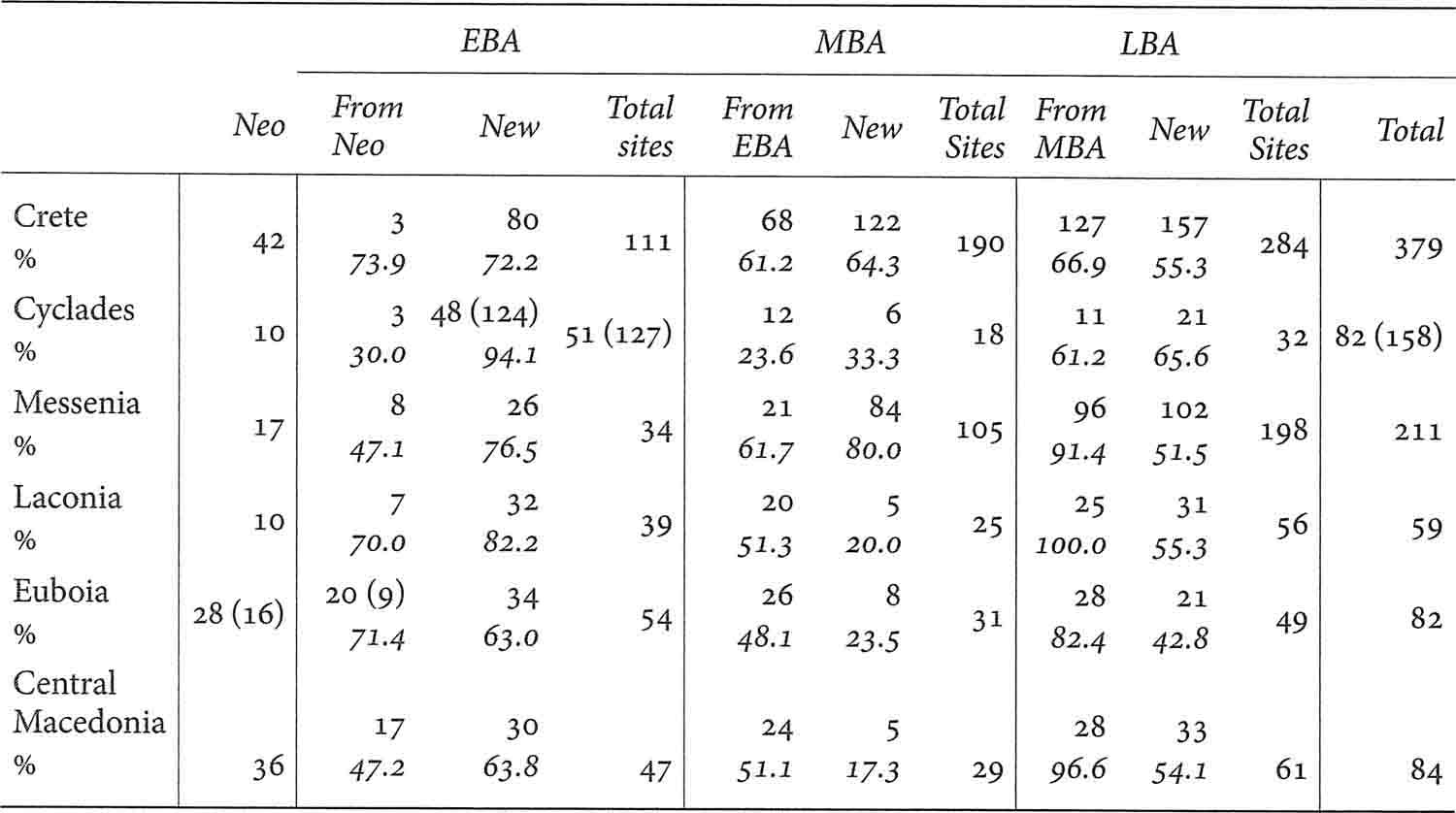

Table 14.3 is based upon the various site surveys in the Aegean which have been made in recent years. The regions surveyed are Crete, the Cycladic islands, Messenia, Laconia, Euboia and Macedonia: their boundaries are indicated on fig. 20.5. The figures for Euboia are from the summary list given by Sackett, Hankey, Howell, Jacobson and Popham (1967, 111), those for Laconia from the table by Waterhouse and Hope Simpson (1961, 164), and for the south-west Peloponnese from the list given by McDonald and Hope Simpson (1969, 161) which conveniently summarises their earlier work. The figures for central Macedonia1 are based on French’s recent review (1967a) taken in conjunction with the information given by Heurtley (1939, XXII-XXIII). In each case, most identifications classed as doubtful have been accepted. The Cycladic figures are based upon the survey reported in the Gazetteer in this volume, together with unpublished survey findings for the middle and late bronze age which supplement the work of Scholes (1956). The figures for Crete are based upon the surveys of Pendlebury (1939), Hood (1965b; 1967) and Hood, Warren and Cadogan (1964), which have been integrated in a useful unpublished paper by Miss Elizabeth Hemingway (1969). The areas quoted are for the total land surface (Ethniki Statistiki Yperesseia 1962a, 2–5.)

The figures at a given period for one region are not necessarily comparable with those for another region, but the patterns of growth, of period-by-period change, are of the highest interest. When the number of settlements recorded per 1,000 sq km of land is plotted for each region and period, notable divergences between the regions emerge.

TABLE 14.3 Period-by-period comparison of observed settlement densities in selected regions of Greece. (The figure for the early bronze age Cyclades excludes locations known exclusively through cemeteries; the total, including such cemeteries, is given in brackets. The figure in brackets for the neolithic of Euboia excludes sites recognised solely on the basis of obsidian finds.)

The number of settlements is plotted on a logarithmic scale in fig. 14.2, and some allowance for the duration of periods is made on the time axis. The number of settlements in each case denotes the total recognised over the period in question: it does not follow that all the sites attributed to a given period were occupied simultaneously.

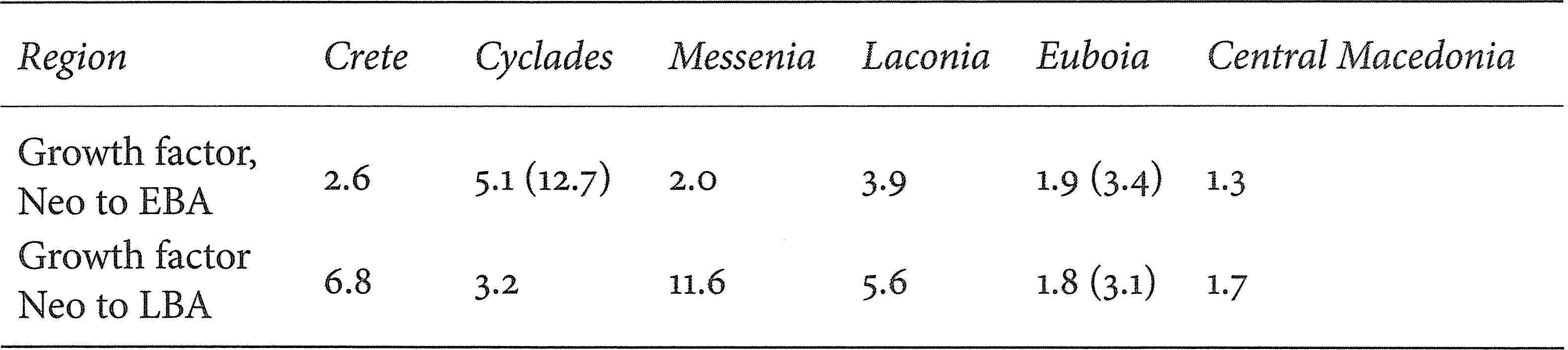

The first and most important feature displayed by this graph is that two growth patterns are seen for the settlements of prehistoric Greece. In two regions, Crete and Messenia, the increase is seen as approximately a straight line. This pattern of growth we may term pattern A. In the three other regions of southern Greece studied, the curve has two peaks, this pattern of growth we may term pattern B (fig. 14.3).

Pattern A, a straight line on a logarithmic scale, approximates to an exponential increase in the number of settlements. This implies a natural and uninhibited growth, without severe restraints imposed, for instance, by very limited food supplies, or other constraining factors. Such patterns of settlement and population growth are familiar in many parts of the world at different times. Viewed in these terms the growth of settlement may be seen as a natural one, without striking discontinuity.

FIG. 14.2 The growth in number of settlements in different areas of the prehistoric Aegean, on the basis of recent site surveys (see Table 14.3).

Pattern B indicates a severe decline in the number of settlements recorded for the middle bronze age. This may be in part due to the shorter duration of that period. And we shall see, in a later section, that while the number of settlements may have been smaller, their individual size may have increased. No decline in human population is necessarily implied, although the growth rate certainly diminished. The recognition of these two differing growth patterns suggests the operation of significant and perhaps identifiable factors in the growth of settlement and population in the prehistoric Aegean.

A consideration of the growth rates over the time range neolithic to early bronze age, and neolithic to late bronze age, is also instructive (Table 14.4).

We see, for instance, that the number of settlements in early bronze age Crete was greater by a factor of 2.6 than in the neolithic period. These figures give a graphic indication of the rapid expansion which was taking place in some regions during the neolithic to early bronze age transition. The diagram, fig. 14.4, contrasts the growth in settlements in the selected regions over the two time ranges in question.

TABLE 14.4 Growth factors from neolithic to early bronze age, and from neolithic to late bronze age, for selected regions in Greece. The survey figures for each period, from which these are calculated, are given in Table 14.3.

The most striking feature of these diagrams is the high growth factor for all the regions of south Greece, over the time span neolithic to early bronze age. The number of settlements in every region increases by a factor of between 2 and 6. But in the one region of north Greece under consideration, central Macedonia, the factor is only 1.3. The distinction between north Greece and south Greece, already indicated in the previous section, is most clearly seen here. It was evidently during the neolithic/early bronze age period that factors came into operation which served to differentiate between settlement densities of northern and southern Greece.

FIG. 14.3 Patterns of growth: two different growth patterns for settlement numbers in the prehistoric Aegean. Pattern A (left): exponential growth (Messenia and Crete); Pattern B (right): retarded exponential growth (Laconia, Euboia, Cyclades).

FIG. 14.4 Comparison of growth in settlement numbers in the prehistoric Aegean:(a) neolithic to early bronze age; (b) neolithic to late bronze age.

The distinction is sustained when the neolithic/late bronze age growth factors are considered, although Euboia has a much lower average growth than the other regions of south Greece. (This may in part be attributed to the exaggeration in the number of neolithic sites recorded in the survey of this region, where 12 sites were classed as neolithic on the basis solely of finds of obsidian and without the corroborative evidence of pottery.) But the Cyclades and Euboia fall back now from their previous leading position. This underlines the suggestion made above that special factors came into play at the end of (or during) the early bronze age which inhibited or negated the multiplication of settlements in these regions.

To recapitulate then, certain fundamental conclusions may be drawn from this analysis:

1. Two very different growth patterns are obtained for settlements in the prehistoric Aegean, patterns A and B.

2. Pattern A presents a picture of exponential growth in settlement numbers.

3. Pattern B shows an increase severely inhibited in the early bronze age/middle bronze age period.

4. A distinction is drawn between north Greece, where growth is slow throughout, and south Greece, where growth is rapid from the early bronze age onwards.

5. The growth inhibition in early bronze age/middle bronze age times, as reflected in the late bronze age figures, is most marked in the Cyclades and Euboia.

Few prehistoric Aegean settlements have been excavated in their entirety. But an estimate of the size of the settlement, that is to say the occupied areas, is often possible, which can at least be used as a basis for order-of-magnitude comparisons.

In Table 14.5, the total area of several prehistoric settlements is listed. Obviously there need be no direct correlation with the population of the settlements. Moreover, for several sites, marked with an asterisk, the estimate is based on the total area of the settlement, usually of a tell mound, which was occupied over a considerable period. At anyone time the occupied area may have been much less. In the settled areas, the density of population undoubtedly varied. Within the limits of a settlement such as Late Helladic Eutresis (213,000 sq m within the circuit walls) large areas might be without habitation, leaving only a reduced area with buildings (35,000 sq m; Goldman 1931, 68) and no reliable estimate of the occupied area can be made without total excavation.

These figures are based upon approximate estimates for the area of settlements, calculated directly from the plans published by the excavators. Although very approximate, they should have an order-of-magnitude validity. These figures are seen diagrammatically in fig. 14.5. The tell mounds, whose settlement area at a specific time is uncertain, and the colossal and largely empty areas enclosed by the walls at two Mycenaean sites, are indicated by broken lines. It should be noted, on the other hand, that the areas for the major late bronze age Minoan settlements are given in some cases by the area of the palace itself. The total settlement area was undoubtedly somewhat larger, but the area of the surrounding buildings is difficult to estimate.

TABLE 14.5 Estimated approximate area of settlement for several major Aegean prehistoric sites.(Asterisks denote sites where the area actually occupied at a given time was probably less than the observed area of settlement.)

| Site | Area: sq m | Source and comments |

| Neolithic(phases II and III) | ||

| Saliagos | 3.700 | Plan: area of island |

| Sesklo | 4,000 | Plan |

| Dhimini | 4,900 | Plan |

| Sitagroi | 7,500 | Plan: estimated area of mound occupied in period III. |

| Argissa | *17,500 | Plan: total area of mound |

| Nea Nikomedeia | *18,000 | Plan: total area of mound |

| Early Bronze Age (Phase IV) | ||

| Panormos (kastro) | 500 | Plan |

| Myrtos | 1,250 | Excavator (Dr P. M. Warren, personal communication) |

| Chalandriani Kastri | 3,600 | Plan |

| Ihermi | 4,500 | Plan |

| Askitario | 5,000 | Plan |

| Zygouries | *6,200 | Plan: total area of mound |

| Troy II | 10,000 | Plan |

| Phylakopi I | 10,800 | Plan |

| Poliochni V (yellow) | 15,000 | Plan |

| Lerna | *21,600 | Plan: total area of mound |

| Korakou | *22,500 | Plan: total area of mound |

| Middle Bronze Age (phases IV–V) | ||

| Malthi | 9,800 | Plan |

| Knossos palace | 13,000 | Plan: palace only |

| Troy VI | 20,000 | Plan |

| Late Bronze Age (Phases V–VI) | ||

| Zakro palace | 3,600 | Plan: incompletely excavated |

| Pylos palace | 7,000 | Plan: palace only |

| Mallia palace | 7,500 | Plan: palace only |

| Aghia Irini | 7,500 | Plan |

| Phaistos palace | 8,100 | Plan |

| Pylos settlement | 12,600 | Plan: area within walls |

| Knossos palace | 13,000 | Plan |

| Gournia | 15,000 | Plan of town |

| Phylakopi III | 18,000 | Plan of town |

| Tiryns | 22,000 | |

| Athens Acropolis | 25,000 | Area within walls |

| Gla, palace enclosure | 31,000 | Area within walls |

| Eutresis, settlement | 35,000 | Excavator: Goldman 1931, 68 |

| Mycenae, citadel | 38,500 | Plan |

| Lefkandi | *45,000 | Plan: total area of mound |

| Eutresis, within walls | *213,000 | Excavator: Goldman 1931, 68 |

| Gla, within walls | *235,000 | plan |

Neolithic village settlement elsewhere in Europe are of comparable size to the Aegean neolithic settlements. For example the early neolithic village of Tell Azmak in Bulgaria has an area of 5,500 sq m; Chotnitsa and Căscioarele (fig. 5.1), of the later neolithic Gumelnitsa culture, of 4,000 and 4,800 sq m respectively; Köln-Lindenthal of the Danubian I culture, 7,500 sq m; and Habaşeşti of the Tripolye culture, 15,000 sq m.

The total areas of the tells of Argissa and Nea Nikomedeia would stand out on the diagram as exceptional if they were taken to represent the total settled area at a given time; perhaps something like half the total was settled at once.

We may then suggest a typical neolithic village size in the Aegean in the range 4,000 to 8,000 sq m, reaching 10,000 sq m (1 hectare, i.e. c.  acres) at times, and rarely perhaps more.

acres) at times, and rarely perhaps more.

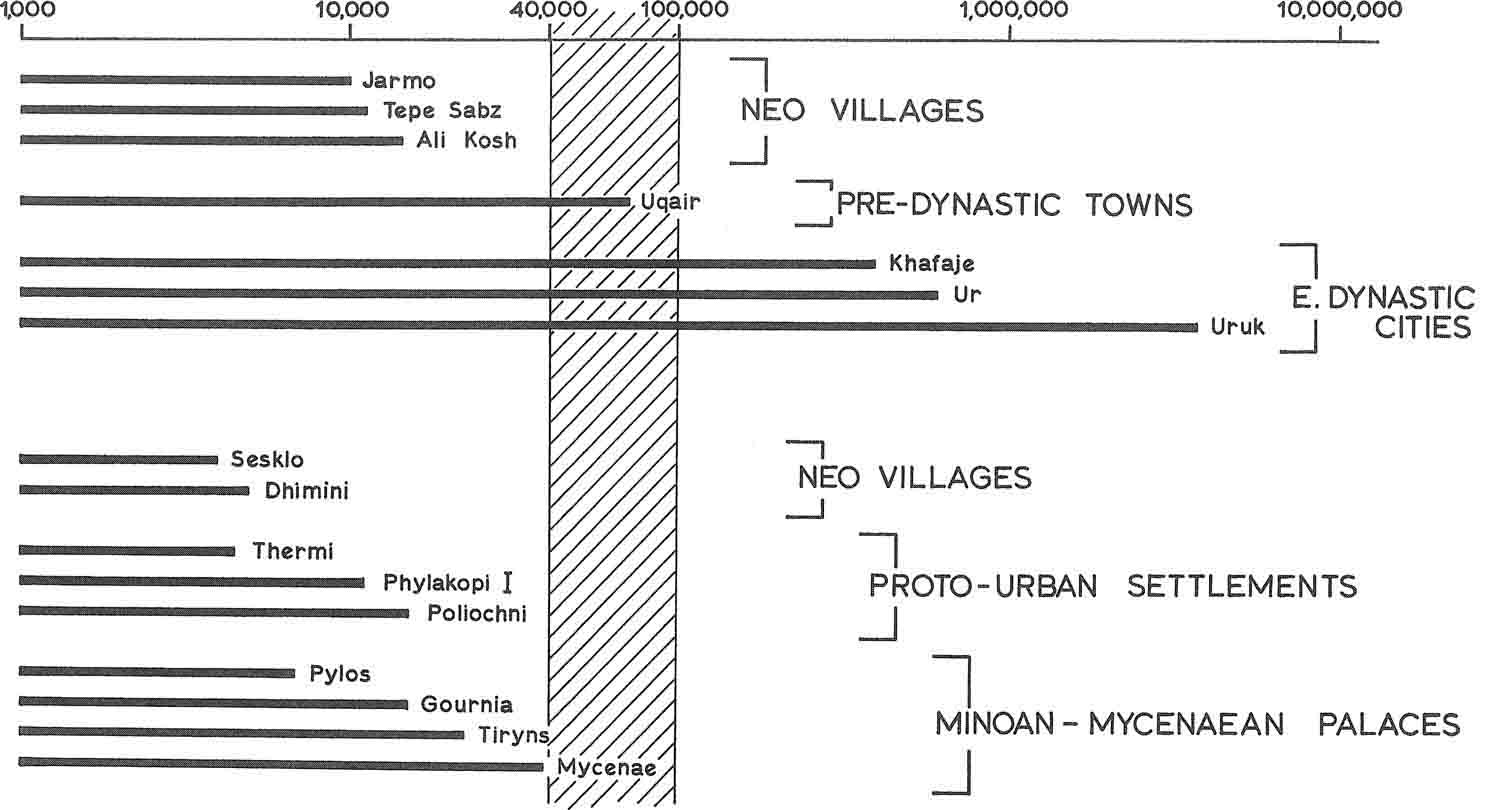

The most striking feature of the early bronze age settlement size is that it is not very notably greater. Once again the total area of tells like Lerna and Korakou may be misleading: perhaps half the total area would represent settlement at a given time. The little forts of Panormos and Chalandriani (fig. 11.4) are perhaps deceptive in the opposite sense, since the main settlement was outside of them. Myrtos (Phournou Koriphi) is a very compact, densely occupied village (fig. 6.5). The proto-urban ‘towns’ of the early bronze age Aegean thus range from 4,500 sq m at Thermi (fig. 8.4) to 15,000 sq m at Poliochni. So that while the larger towns are perhaps twice the size of a neolithic village, the smaller ones do not differ from their predecessors in terms of size. These early bronze age ‘towns’ are less than 2 ha in area.

The palaces of the middle and late bronze age are not strikingly large: the palace at Zakro is the same size as an average neolithic village; that at Knossos compares with the earlier ‘town’ at Poliochni. Of course the Cretan palaces did not stand alone: at Knossos an interesting series of smaller villas and ‘palaces’ has been excavated, and blocks of houses at Mallia. In no case, however, has the surrounding area been adequately investigated, and Gournia alone gives a good impression of a Minoan town (15,000 sq m). Grandiose estimates have been made for the town at Knossos. Hutchinson (1950, 206) quotes a possible population of 100,000. Using Frankfort’s estimate (1950, 103) of population density in a Sumerian city of 400 persons per hectare, this would lead to an area of settlement of 2,500,000 sq m ( sq km). This exceeds the entire Knossos region by a factor of 10 and cannot be accepted as realistic. The palace and fortified enclosure at Pylos may give a firmer indication, where the palace occupies about half the total area enclosed by the walls. Probably the settled area at Knossos did not exceed 30,000 to 50,000 sq m: greater than the town at Phylakopi, and comparable with the area of settlement at Mycenae or Tiryns. The relatively small size of the entire settlement at Pylos or Aghia Irini in Kea indicates that a palace settlement complex did not need to be much greater than one hectare in area.

sq km). This exceeds the entire Knossos region by a factor of 10 and cannot be accepted as realistic. The palace and fortified enclosure at Pylos may give a firmer indication, where the palace occupies about half the total area enclosed by the walls. Probably the settled area at Knossos did not exceed 30,000 to 50,000 sq m: greater than the town at Phylakopi, and comparable with the area of settlement at Mycenae or Tiryns. The relatively small size of the entire settlement at Pylos or Aghia Irini in Kea indicates that a palace settlement complex did not need to be much greater than one hectare in area.

FIG. 14.5 The increase in the size of prehistoric Aegean settlements. Approximate settlement area is indicated (cf. Table 14.5). (Tell settlements whose settled area at anyone time may have been less than the measured area are indicated by dotted lines; only part of the space within the walls at Gla and Eutresis was actually settled.)

We may set the size range of a typical late bronze age Aegean major settlement as from 10,000 to 40,000 sq m.

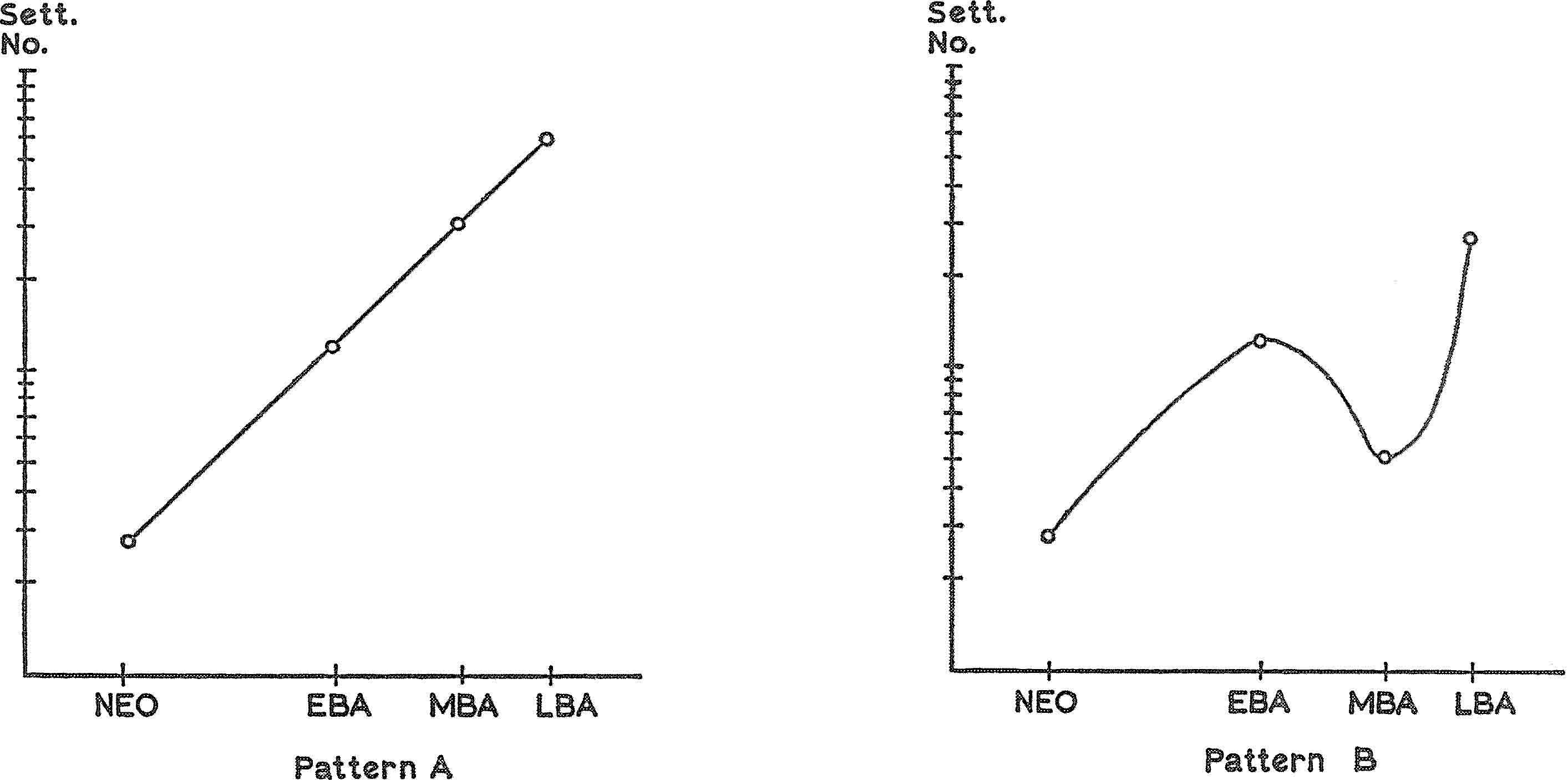

To appreciate the significance of this rather slow growth in size, whereby the area of settlement from neolithic village to late bronze age town increases by a factor of only 10, comparison with the Near East is useful. In the following list (Table 14.6) the areas of a number of Near Eastern settlements, from early neolithic to Early Dynastic times, are given. As before, it does not follow that the entire area within the settlement was occupied, nor is population necessarily proportional to area. Once again, tell sites, where the total area is given rather than the area occupied at a given time, are indicated by an asterisk.

TABLE 14.6 Estimated approximate areas of settlement for several early Near Eastern sites.(Asterisks denote sites where the area actually occupied at a given time was probably less than the area of settlement.)

| Site | Area: sq m | Source and comments |

| Neolithic / Chalcolithic | ||

| Jarmo | *10,000 | Plan |

| Ali Kosh | *14,000 | Plan |

| Tepe Sabz | *11,200 | Plan |

| Hacilar | *18,700 | Plan |

| Can Hasan | *75,000 | Estimated from excavators measurements, French 1962, 27 |

| Çatal Hüyük | *120,000 | plan |

| Predynastic | ||

| Uqair | 70,000 | Quoted by Hole 1966, 607 |

| Early Dynastic/Bronze Age | ||

| MBA Jericho | 38,000 | Plan |

| Beycesultan | *60,000 | Plan |

| Khafaje | 400,000 | Quoted, Hole 1966, 607 |

| Ur | 600,000 | Quoted, Hole 1966, 607 |

| Uruk | 4,500,000 | Plan |

These figures may usefully be considered in the light of the size-definitions for village, small town, and large town, formulated by Adams (1965, 39) for Early Dynastic sites in the Lower Diyala region of Mesopotamia. ‘Large towns are defined as ‘more than 10 hectares in area’, ‘small towns as ‘4–10 hectares in area’, and ‘villages’ as ‘less than 4 hectares in area’. On this scale middle bronze age Jericho and Beycesultan have the areas of small towns, while Ur and Khafaje are very properly large towns in terms of size. Uruk, the largest of the Sumerian cities is, of course, vast in this context ( sq km), bigger than Republican Rome, and twice the area of Themistoclean Athens.

sq km), bigger than Republican Rome, and twice the area of Themistoclean Athens.

FIG. 14.6 Comparison of settlement size in the prehistoric Aegean and Near East. Note the limited growth in the Aegean, where irrigation was not practised (cf. Table 14.6).

Size is not, of course, on its own a valid criterion for towns or cities, and a consideration in terms of function (cf. Chapter 18) is also necessary. Function, variety and specialisation cannot, however, be determined archaeologically without extensive excavation, and the only possible comparative procedure open to the archaeologist is the consideration in terms of settlement area.

In Early Dynastic terms, Predynastic Uqair and the tell of chalcolithic Can Hasan have the areas of small towns; neolithic Çatal Hüyük that of a large town. The other neolithic sites listed are fair-sized villages. We should notice that a large town in Mesopotamia is a hundred times the size of a small village.

These figures permit a general comparison of the growth in size of the Aegean settlements with those of their Near Eastern counterparts. Some of the Aegean settlements are compared, at the same scale, with Uruk in fig. 14.8. Figure 14.6 compares the size development of the Near Eastern sites considered with the developmental pattern established in fig. 14.5 for the Aegean. The Anatolian sites (Çatal Hüyük, Hacilar, Can Hasan and Beycesultan) are not shown, but the exceptionally large size, for a neolithic site, of Çatal Hüyük must be noted. The scale for the areas is now a logarithmic one. The shaded arms indicates the size range suggested by Adams for ‘small towns in Early Dynastic Mesopotamia.

The important conclusion is that typical Aegean prehistoric settlements did not exceed in area a total of 4 hectares (40,000 sq m), the figure which in Early Dynastic Mesopotamia marks the upper size limit of a village.

FIG. 14.7 Diagrammatic simplification of settlement growth in the Aegean and the Near East. The neolithic villages in both regions were of comparable size, and in both regions the growth was exponential―in the Near East to the base 10, in the Aegean to the base 2.

Naturally there may be exceptions (although the walls of Gla and Eutresis, as explained above, can reasonably be discounted for the present purpose). In Crete, the existence of an urban agglomeration around two of the palaces has been suggested, and the region at Knossos, believed by Evans (1921–35) to encompass the Minoan town is shown in fig. 14.8. Hood’s map of the Knossos region would suggest an area of about 500,000 sq m for the urban settlement, and the supposed town of Mallia has been as-signed a slightly smaller area (Demargne and Callet de Santerre 1953, pl. 1). But the evidence for dense occupation within these areas is not convincing, and even Knossos and Mallia are scarcely comparable to an Early Dynastic Sumerian town.

FIG. 14.8 Early Aegean sites compared with Early Dynastic Uruk, all at the same scale. The clotted lines indicate the extent of the ‘lower town’ at Mycenae, the supposed area of settlement around the palace of Mallia, and the ‘inner town’ and ‘outer town’ around the palace of Knossos, as indicated by Evans. (It is doubtful whether the areas of settlement at Mallia and Knossos were in fact so large.) Most of the area within the walls at Uruk was densely occupied.

In the Near East, before 5000 BC, Çatal Hüyük had already gone beyond village or ‘small town’ scale, equalling the size of the ‘large towns’. In general, however, the larger neolithic settlements of the Near East are still ‘Villages’ of area up to 4 ha, the larger predynastic settlements ‘small towns up to 10 ha, and the larger Early Dynastic settlements ‘large towns of up to 1 sq km in area. The larger Minoan-Mycenaean towns were no larger than a fair-sized village of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia.

The growth factor in the Aegean was thus much smaller than in the Near East. Both areas nurtured small early neolithic villages, of comparable size. But the proto-urban settlements of the Near East were some ten times greater in area than these early villages, and the large Early Dynastic towns about ten times larger again. In the Aegean these increases take place with a ratio of two, not of ten.

The point is most succinctly expressed in the diagram, fig. 14.7, which brings out one of the fundamental differences between Aegean civilisation and the ‘irrigation civilisation’ of the Near East. In both cases the scale is logarithmic, for the Near East to the base 10, for the Aegean to the base 2.

We may note in passing that the Indus civilisation cities of Mohenjo-Daro (670,000 sq m) and Harappa (350,000 sq m) are of the same order of size as their Mesopotamian contemporaries.

McDonald and Hope Simpson (1969, 175) have rightly written: ‘If urbanisation requires (among other features) a really sizeable concentration of population at urban centres, it is questionable whether the term can properly be applied to Mycenaean civilisation at any stage’ This fundamental point, documented above, must always be in our minds if we are to avoid the trap of supposing that the origin of the Aegean civilisations is essentially analogous to those of Mesopotamia or of Mexico. Their scale was not the same.

A comparison of some leading Aegean prehistoric settlements with the major Sumerian city of Uruk is given in fig. 14.8. Nothing could more emphatically illustrate dangers of equating the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation with Mesopotamia.

The typical Aegean early bronze age settlement was indeed larger than its neolithic predecessors―perhaps covering 10,000 sq m now instead of 5,000 sq m. And the Minoan-Mycenaean palace settlements were larger again, typically of 20,000 sq m. This growth in size is an important factor for the understanding of Aegean civilisation, but far from a dominant one, as it may have been in the Near East.

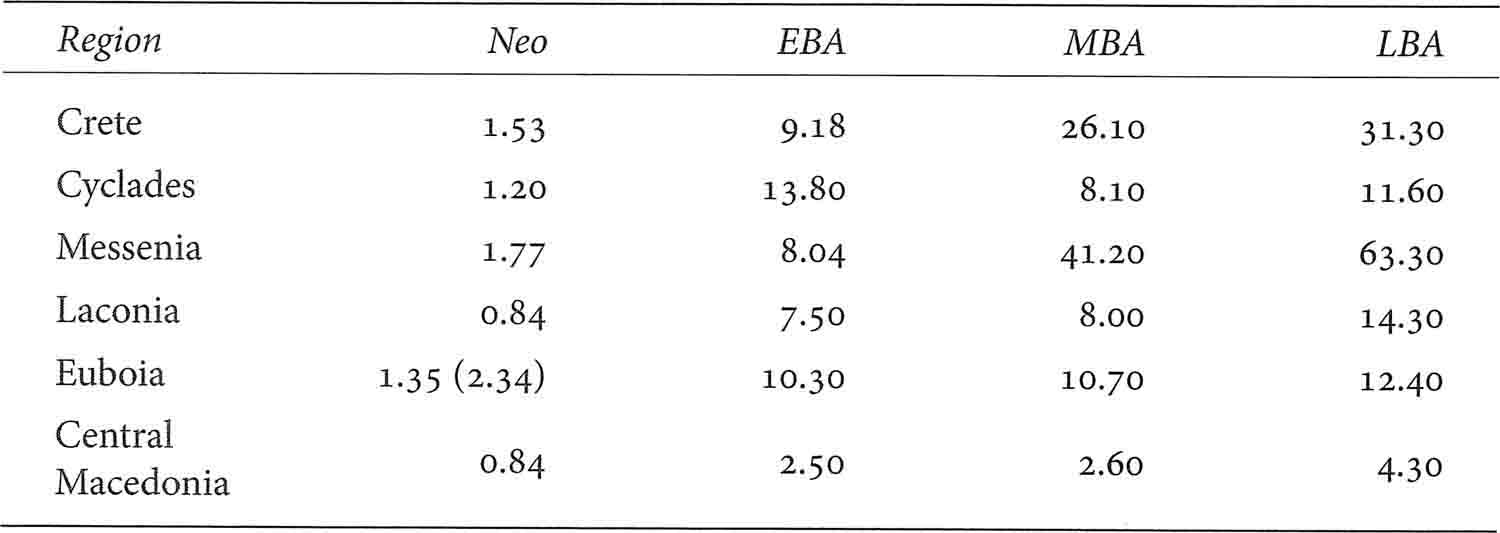

The site survey data already used can also yield information about the continuity of settlements. Again, one region may not be comparable with another, but the period-by-period comparison within a given region is of interest. The basic data, from the same sources used for Table 14.3, are given in Table 14.7.

There are various ways by which these data may be analysed. To the best of my knowledge the question of continuity has never previously been considered on a detailed quantitative basis. Yet it is highly relevant to the whole question of transferences of population, with consequent discontinuity of occupation. Once again there are several cautionary factors. In the first instance the presence of finds of neolithic, early bronze age, middle bronze age, and late bronze age data at a site does not necessarily imply continuity of occupation throughout the period in question, since each of these chronological divisions was itself of long duration. The absence of finds from many sites on the other hand, does not document abandonment, since excavation is necessary to establish the absence of material representative of a given period. Surface collection alone is insufficient.

TABLE 14.7 Continuity in the occupation of settlement sites from one period to the succeeding period. The table shows the number of sites in each period which are newly occupied (i.e. not known to have been occupied in the previous period), and the number with continuity of occupation. The percentages indicate in each case, first the percentage of sites of the previous period which remain in occupation, and secondly the percentage of sites in the period in question which are newly occupied. The final total is the total number of prehistoric sites recorded in the area in question.

Two sets of histograms for each area are seen in fig. 14.9. The first set indicates the percentage of sites in the period that continue in occupation into the next. The second shows the percentage of settlements in each period which were not settled (or at least have not produced evidence for settlement) in the previous period. This then gives the proportion of new sites in each period.

If, for example, we consider the early bronze age/middle bronze age transition in Crete, we see that 61 per cent of Early Minoan sites were still in use in the Middle Minoan period (these sites constituting 36 per cent of the total sites in the Middle Minoan period). 64 per cent of Middle Minoan sites are new.

We see then that in general, from one period to the next, there is at first sight a fairly high continuity. With the exception of the Cyclades, between 47 per cent and 74 per cent of neolithic sites continued to the early bronze age, and between 48 per cent and 62 per cent from the early bronze age to the middle bronze age. We may note that the figure of 61 per cent for Crete (Early Minoan to Middle Minoan) where the actual archaeological material demonstrates undoubted continuity, is not strikingly higher than for some other areas, where certain authors have suggested a change of population. We may note too that the high figure of 70 per cent for the neolithic to early bronze age transition in Crete, paralleled in Laconia, does not strongly suggest the advent of a new population.

FIG. 14.9 Continuity in the occupation of settlements in the prehistoric Aegean. On the left, the histograms indicate the percentage of sites in each region which continued to be settled in the succeeding period. On the right, the histograms show the percentage of sites in the appropriate period which were newly settled (cf. Table 14.7).

For the middle bronze age to late bronze age transition, between 61 per cent and 100 per cent of settlements persist into the late bronze age, although we should note that the higher percentage may in part be connected with the shorter length of time involved.

The low figures for the Cyclades are striking, as is the high percentage of settlements that are on new locations at the beginning of the early bronze age period. This might suggest the influx of new people, or a situation of unrest, or alternatively, a considerable population explosion with the consequent foundation of many new settlements. A simple change in settlement pattern could produce the same result.

The histograms indicating the percentage of sites that are new clearly reveal in addition the reason for the decline in settlements recorded in some areas during the middle bronze age, as observed in the last section. This was not due to an increase in the abandonment of sites, for the wastage, as indicated by the histograms just discussed, did not change markedly. The new factor is the decline in the rate of foundation of new settlements. The decline then in the settlement density (if it does represent a true decline, rather than reflecting the shortness of the period) was the product of the natural wastage of sites, at a normal rate, together with the failure to set up new ones. It is at this period that the shorter duration of the middle bronze age, less than half that of the early bronze age, is relevant. The percentage of new sites per century in the middle bronze age was actually greater in Crete and Messenia than during the early bronze age.

Finally, one more test may be applied. Knowing the number of sites recorded as occupied in a specific period (say the neolithic), and the number of sites recorded as occupied in the next period (say the early bronze age), we may calculate how many of these sites one would expect to have been settled at both periods, given a random arrangement. (This implies that all the sites in question had an equal chance of being settled in the first period, and that they all had also an equal chance of being settled in the second.) We may therefore compare the observed figures with those predicted for a random distribution, to see whether there is a notably strong correlation between successive periods.

The observed figures are of course available. The predicted figures are calculated knowing the number of sites occupied in period ‘a’ (Na) and the number occupied in period ‘b’ (Nb). The predicted figure is2  .

.

The observed and predicted values for sites continuing in occupation from one period to the next are given in Table 14.8. Such analyses as this have not previously been undertaken, and the interpretation of the figures in Table 14.8 is not easy Clearly the Cyclades fall below the general level of continuity but the number of sites there, for the neolithic period at least, is so small as to be of limited significance. What emerges most clearly is the high continuity in most regions, especially from middle bronze age to late bronze age, but this could again relate largely to the short duration of the periods in question.

TABLE 14.8 Comparison between the number of sites occupied in successive periods, and the number predicted by the formula  . The ratio is the number of observed sites occupied in both periods, divided by the number of sites predicted. (The maximum possible ratio is 4.0.)

. The ratio is the number of observed sites occupied in both periods, divided by the number of sites predicted. (The maximum possible ratio is 4.0.)

In general the histograms of fig. 14.9 seem to give the clearest indication of the underlying processes at work. In general the deciding factor was not the number of sites which continued to be occupied, a high figure except in the Cyclades. It was, rather, the number of new settlements founded.

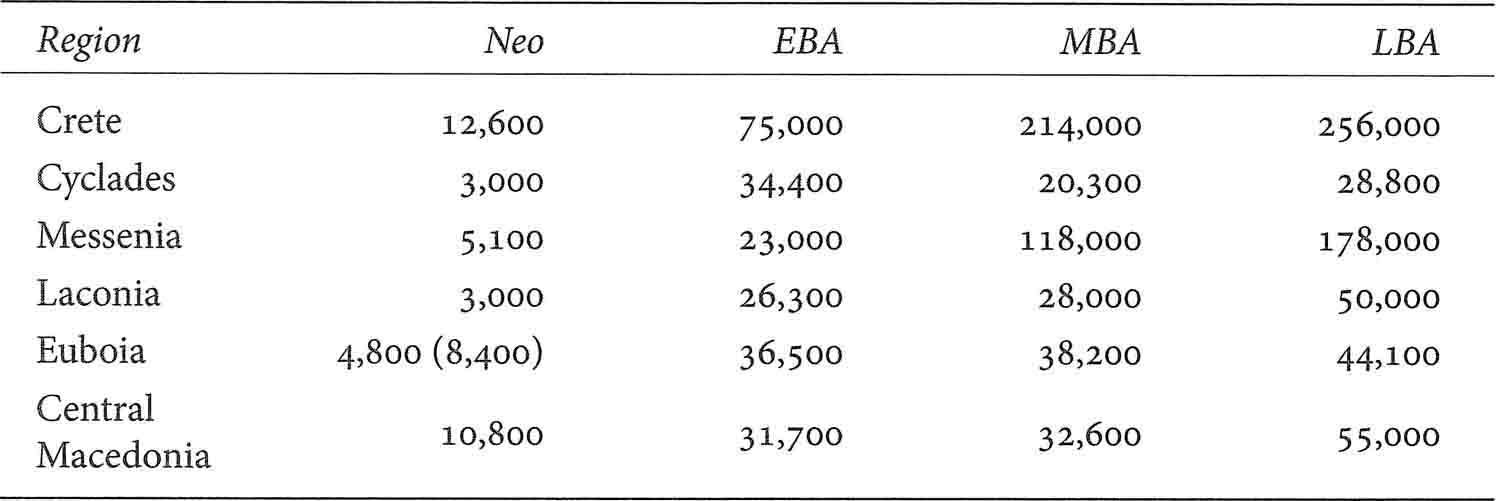

Having studied the settlement figures we may now go ahead to use them for the estimation of the prehistoric human population.

The determination of early population figures is a notoriously difficult task. All the discussion so far, in dealing with settlement pattern, has deliberately been set in relative terms. We do not know the original real settlement density: we can speak with precision of the observed density of occupation.

Yet in order to visualise the societies with which we are dealing, their problems of subsistence, and of social organisation, some notion of absolute figures is needed. It can plausibly be argued that the single most significant feature which distinguishes the modern world from the ancient world is the greatly increased density of population. Many of the largest population centres in the ancient world would barely rank as towns today in terms of size.

In the foregoing sections, the observed density of settlement has been calculated, and the approximate size of settlements in each period discussed. These estimates can now be made to form the basis for calculations towards a tentative figure for the prehistoric population in each of the regions in question.

This entails estimates for two factors. The first, and crucial, step is to suggest what proportion of prehistoric settlements originally in existence are represented in the survey data now available.

Although this factor is exceedingly difficult to estimate, one result already obtained may be helpful. We have seen that the number of Cycladic early bronze age sites known, if cemeteries be included, is 127. Yet, if we count only those sites known also from the settlement remains, the number is reduced to 51 (Table 14.3). The latter figure is much more in harmony with the data from other regions, and was utilised in the graph, fig. 14.2. The apparent distortion resulting from the use of the larger figure is seen in fig. 14.10.

The reason for this high, perhaps disproportionately high, figure for the Cycladic early bronze age is easy to pinpoint. It is large because the early Cycladic cemeteries are today very easily discovered, difficult to destroy and rich in saleable finds, which bring them to the attention of archaeologists and others. These finds have excited interest since early in the last century. The graves are generally cist graves, built of large flat slabs of marble and schist. Safely buried underground, these very effectively preserve the contents. It follows, then, that we are more likely today to have a tolerably good knowledge of cemeteries in the Cyclades than of settlements there or in other areas.

The difference between the cemeteries known and the settlements recognised is thus a highly significant one. It seems likely, since every cemetery obviously had an accompanying settlement in prehistoric times, that the figure of 127 is a better estimate for prehistoric settlements in the islands than is 51. This suggests that in the early bronze age Cyclades, it may be necessary to multiply the figure for observed settlements (51) by a factor of 3 to obtain a more reasonable estimate of the original number of settlements. The same may conceivably hold for other regions.

It Is proposed therefore that to obtain an approximation for the original total number of settlements in the Aegean early bronze age, the figure for the observed settlements be multiplied by a factor of 3. Since late bronze age pottery is very characteristic, especially in southern Greece, and of course near the surface on deeply stratified sites, a factor of only 2 is proposed for the late bronze age, and a factor of 2.5 for the middle bronze age. For the neolithic period, where sites are not always easy to recognise, a factor of 4 is suggested.

FIG. 14.10 Growth in settlement numbers in the Cyclades. The continuous line refers only to sites where actual settlement remains have been found, the broken line includes also those locations known solely from cemetery finds.

The second problem facing us is the average population per settlement. Here the estimates of settlement size are useful. The figures of 5,000 sq m, 10,000 sq m, and 20,000 sq m for the neolithic, early bronze age and late bronze age periods of the Aegean were obtained above (fig. 14.7). A figure of 15,000 sq m may be taken for middle bronze age settlements.

In converting these areas to population figures we may refer to Frankfort’s estimate for Mesopotamian urban sites, where he suggested a population density of 400 persons per hectare (1950, 103). Even in late bronze age times In the Aegean, the population was probably not so closely packed together as in a Sumerian town. So 300 persons per hectare will be taken here for the early bronze age, middle bronze age and late bronze age periods, when Aegean settlements were of urban or proto-urban nature. For the neolithic period, when houses were sometimes more widely spaced, a figure of 200 persons per hectare is suggested.

This gives an estimated population for an average settlement in the neolithic period of 100 persons, for the early bronze age period of 300 persons, for the middle bronze age of 450 persons and for the late bronze age of 600 persons. Conceivably the areas of settlement utilised reflect in each case the upper limits of settlement size for the period in question rather than an average. If this be so, the average population per settlement in each period may have been less than the estimate reached here. The estimated figures for total population in each region may thus err on the side of generosity.

Finally it is necessary to guess how many of the settlements observed in each period were actually occupied at the same time. For the neolithic, early bronze age and late bronze age periods, each 500 years or more in duration, a figure of  is suggested. For the middle bronze age, which was rather shorter, the assumption is made that the settlements observed were simultaneously occupied.

is suggested. For the middle bronze age, which was rather shorter, the assumption is made that the settlements observed were simultaneously occupied.

These figures now enable a calculation of the population for each area. For example, survey of Crete has yielded 284 late bronze age sites. The factor of 2 suggested implies that the original total of late Minoan sites was 568. A factor of  indicates that 426 late bronze age sites may have been occupied at once. An average of 600 persons per settlement, as suggested, yields a total population in late bronze age Crete of 260,000 persons. The same procedure for other regions leads to the population estimates given in Table 14.9.

indicates that 426 late bronze age sites may have been occupied at once. An average of 600 persons per settlement, as suggested, yields a total population in late bronze age Crete of 260,000 persons. The same procedure for other regions leads to the population estimates given in Table 14.9.

TABLE 14.9 Estimated approximate population figures for various regions of prehistoric Greece. (The figure in brackets for neolithic Euboia includes sites known only from finds of obsidian.)

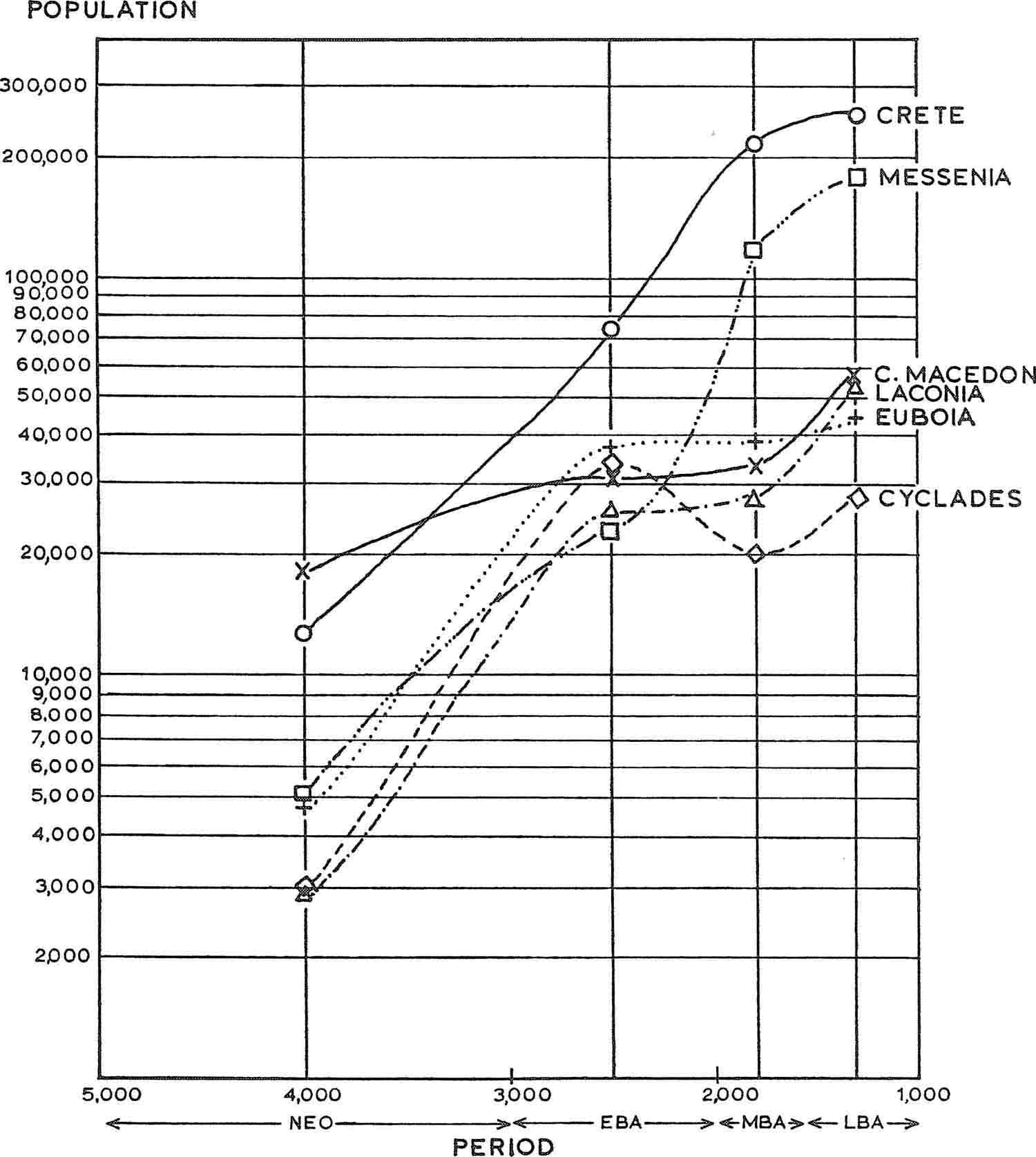

These figures are plotted, again on a logarithmic scale, on fig. 14.11.

The distinction between the growth pattern A and B discussed above is a very clear one still. But it is now only in the Cyclades that a positive decline in population is seen during the middle bronze age. In other regions of pattern B the population is effectively stationary at this time, but it does not decline.

FIG. 14.11 Estimated growth of population in the prehistoric Aegean (cf. Table 14.9).

Table 14.10 uses the same data to calculate the estimated population per square kilometre at each period.

These figures are plotted on a logarithmic scale on fig. 14.12. We see that the estimated population density in neolithic times lay between 0.8 and 1.6 persons per square kilometre for the different regions. From then on the regions of southern and northern Greece diverge markedly, since the population density in central Macedonia rises only very slowly.

In southern Greece the early bronze age population density lies between 7.5 and 14. This is a striking increase, by a factor of 10, over the neolithic density. In the middle bronze age the figure lies between 8 and 42: it is the regions of growth pattern A which are now setting the pace. And in the late bronze age the variation is between 11 and 63. The regions of pattern B have increased little, if at all, over the early bronze age figure, those of pattern A by a factor of 3 and 8 respectively.

These figures form the fundamental background to the development of Aegean civilisation. They compare surprisingly well with more recent population figures for the different regions (Renfrew 1971).

TABLE 14.10 Estimated approximate population densities for various regions of prehistoric Greece, expressed in number of persons per square kilometre. (The figure in brackets for neolithic Euboia includes sites known only from finds of obsidian.)

There are few estimates for the population of regions in classical Greece with which these figures may be compared. Beloch (1880) calculated for Euboia that, since there were 3,000 hoplites at the battle of Nemea in 394 BC, there might have been 12,000 citizens, and hence 36,000 free people. He estimated the total population of Euboia at that time as 70,000 persons. This compares reasonably with the suggested figure here for late bronze age Euboia of around 45,000 persons.

Turning now to the Cyclades, assuming a late bronze age population of 30,000, we might expect Tenos (which in 1961 numbered 12,000 out of a total for the Cyclades, of 140,000, i.e. 9 per cent) to have had a population of 2,700 in the late bronze age. On the basis of Roman tax returns Beloch calculated a free population of 2,220 persons (740 citizens): the total population, including slaves, would have been greater.

Unfortunately the classical population figures are at least as doubtful as the prehistoric ones, and cannot give any firm corroboration.

The settlement densities (Table 14.10) can also be used for purposes of comparison. Hole and Flannery (1967, 202) have made estimates of the developing prehistoric population of south-west Iran. They suggest a density of 2.3 persons per sq km in the early dry farming stage, rising to 6 per sq km in the fourth millennium period of village specialisation. In the Diyala region of Mesopotamia, the density may have increased by Early Dynastic times to 68 persons per square kilometre of irrigated land (Adams 1965, 24), equivalent to around 54 persons per square kilometre of total land. These are in fact the population figures for that region today. It is not surprising that the prehistoric settlement densities in the Aegean should in general have been less than those for irrigated lands in the Near East. Messenia and Crete apparently did reach comparable densities, through the practice of Mediterranean polyculture under palace direction, as succeeding chapters will show. There is no contradiction here, however, since Messenia today actually has a population density (88 persons per sq km) considerably greater than that for the irrigated lands of the Diyala region.

In conclusion, Godart’s (1968, 63) minimum estimate of 4,264 dependents at the Late Minoan palace at Knossos is relevant. It is reached on the basis of ration records of grain. A further approach from the tablets is to use estimates for the stock controlled by the palaces of Knossos and Pylos. These, as discussed in Chapter 15, are of the order of 80,000. In Crete in 1961 there was a human population of 525,000, and 870,000 stock (including 507,000 sheep). An order-of-magnitude estimate for the population within the lands controlled by Knossos (as defined by the sheep tablets and using the modern ratio of sheep to people) would be around 50,000. This is one fifth of the total population estimate reached for late bronze age Crete. The conclusion that the palace at Knossos controlled economically about one fifth of the populated lands of Crete seems a plausible one. It seems reasonable too that a total population of 50,000 in the territory controlled from Knossos should have supported around 4,000-5,000 persons in the palace itself.

FIG. 14.12 Estimated population densities in the prehistoric Aegean.

In the Aegean early bronze age, as we have seen, fortified proto-urban settlements made their appearance, and were followed in southern Greece by the palace centres of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisations. In size these proto-urban and palace settlements were not often vastly bigger than neolithic villages, and certainly smaller than the contemporary Near Eastern towns and cities. In many areas the majority of neolithic sites continued in occupation into the early bronze age, and nearly everywhere the middle and late bronze age settlements built upon the pattern established in the early bronze age.

While in Crete and Messenia, on the one hand, growth was as rapid in the middle bronze age as in the early bronze age, so that there are more middle bronze age than early bronze age sites recorded, for the other regions considered (Laconia, Euboia and the Cyclades, as well as Macedonia), actually fewer middle bronze age than early bronze age settlements are known. And while, admittedly, the middle bronze age was shorter, so that one might argue that there is an overall increase in the number of settlements recorded per century, the difference in the two patterns of growth is striking. It will be convenient now to look in more detail at two regions representative of these different growth patterns: Messenia and the Cyclades.

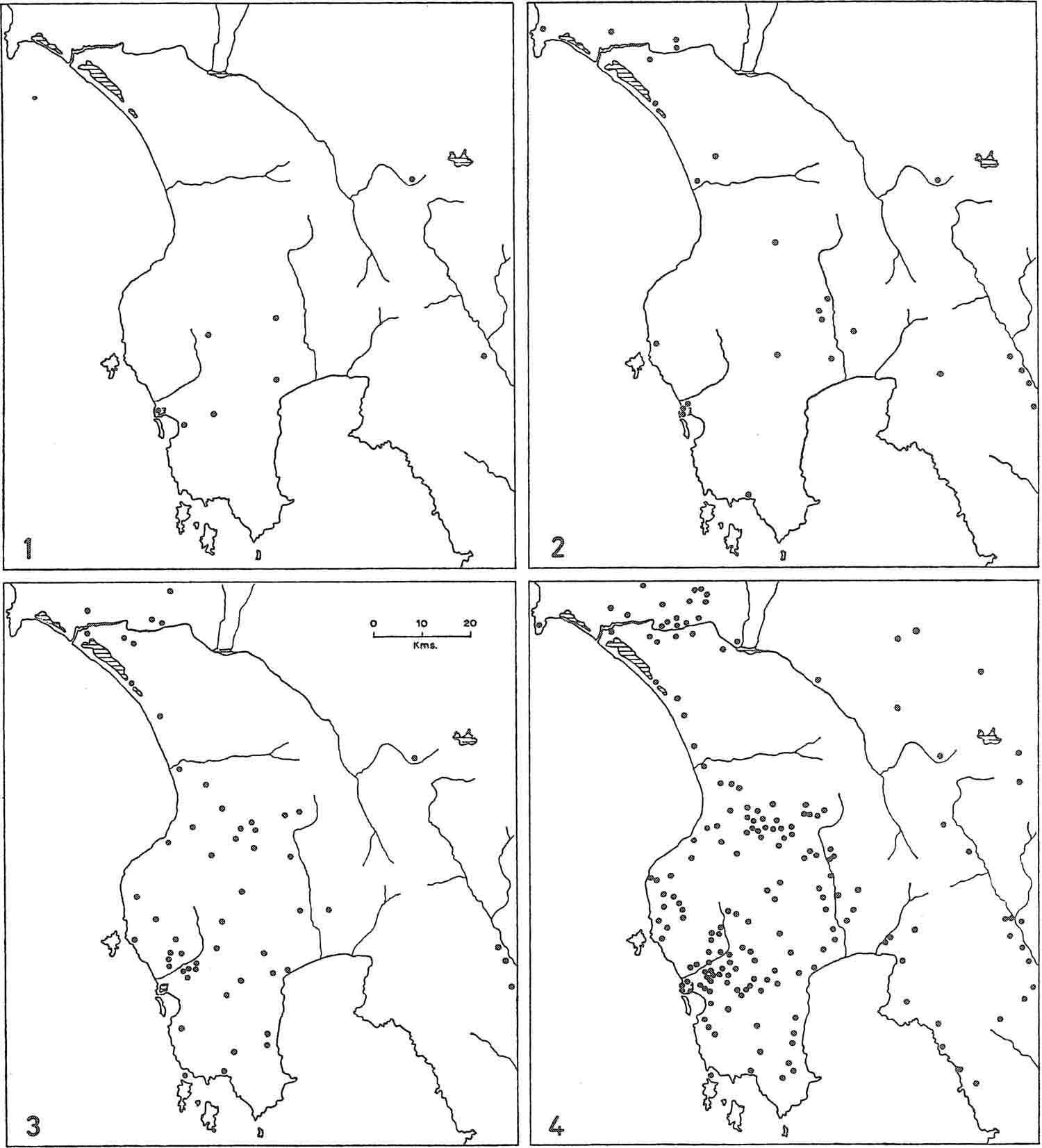

Messenia and Crete both saw a rapid and uninterrupted increase in population during the bronze age, resulting in a density of population more than twenty times that in the neolithic period. The growth of settlement in Messenia for the neolithic through the successive phases of the bronze age is seen in fig. 14.13. It gives a vivid picture of sustained growth.

The development of prehistoric settlement in Messenia has been admirably outlined by McDonald and Hope Simpson in their survey (1969,172). They point out that almost half the early bronze age sites were situated on the coast, while the remainder are along river valleys, principally the Alpheios and the Pamisos.

During the middle bronze age there is a marked increase in population, and the areas with notable concentrations of Early Helladic population continue to be settled. We have seen above that 62 per cent of early bronze age sites in Messenia continued in occupation to the middle bronze age, a figure rivalled only by Crete (61 per cent) and contrasting with 25 per cent and 48 per cent for the Cyclades and Euboia. Many new villages were founded―it is only in Crete and Messenia that the number of new villages founded in the middle bronze age exceeds the number surviving from the early bronze age and only in these regions therefore that the total number of settlements actually increases. At this time there is the penetration of what has been termed ‘marginal or isolated territory’ for reasons which are discussed in the next chapter.

FIG. 14.13 Settlement growth in prehistoric Messenia.1, neolithic period; 2, early bronze age; 3, middle bronze age; 4, late bronze age. (based on data by McDonald and Hope Simpson).

A significant change is that only 15 per cent of the Middle Helladic sites were coastal, a reduction by a factor of three on the Early Helladic proportion. As McDonald and Hope Simpson (ibid., 174) remark: ‘It looks as if these people, like their successors, in certain phases of the medieval period, preferred security to accessibility.... Time after time we found that we must “raise our eyes unto the hills”, that virtually no strategically located isolated height near good water and reasonably fertile land can be overlooked.... Indeed the “hill fortress” becomes a kind of canon.’

The fortified site of Malthi in terms of the settlement type of the period, may be taken as ‘the model―a small town on a high rough hill, first occupied in a major sense in Middle Helladic times, and apparently fortified in that period’ (Valmin 1938). It had an area of about 1 hectare (10,000 sq m) and a population therefore of up to about 300 persons. It was entirely enclosed by a fortification wall.

During the late bronze age population continued to increase (until the end of the Late Helladic IIIB period). In Messenia as in Crete there are again more new sites at this time than sites continuing from the previous period. But equally the majority of middle bronze age sites continued in occupation―in Messenia more than 90 per cent of them.

At this time palace centres, such as Pylos, were emerging. The description by McDonald and Hope Simpson (1969, 175) is again relevant: ‘The Early Mycenaean period certainly witnessed dramatic social, political and economic changes, even if (in Messenia at least) there was no rapid Increase in local population, and no large-scale immigration from outside. The developments most obvious to us now are vastly improved means of producing or acquiring moveable wealth (royal mainly?), and the appearance of specialised occupations and skills, evidenced by such phenomena as wide foreign trade and tholos tombs. In addition there is a distinct possibility that literacy had begun to establish itself at local capitals. Traits of the sort described above are usually linked with what the culture historians call “incipient urbanisation”. But if urbanisation requires (among other features) a really sizeable concentration of population at administrative centres, it is questionable whether the term can properly be applied to Mycenaean civilisation at any stage.’

A fairly clear picture emerges from the survey of the steady development of settlement and population. It is significant that middle bronze age sites show, by their location, that problems of security were now important. But evidently these problems were solved, for the population continued to increase and prosper. Sections 2, 3 and 4 of fig. 14.13 illustrate that whatever the defensive problems in the middle bronze age the population density increased.

The development of settlement in Crete is not identical to that of Messenia, although their growth patterns are remarkably similar. Both differ from the areas of pattern B in the continuing expansion in the middle bronze age. Crete, however, shows no sign during the middle bronze age of the security problems which evidently troubled Messenia in common with other regions. There is no emerging preference for acropolis sites in Crete at this time, nor are the settlements fortified.

At the end of the Late Minoan lb period in Crete a number of major sites were abandoned, but in fact Pendlebury lists more sites for Late Minoan III Crete than for Late Minoan I. It is not until the end of the Late Minoan period that a ‘flight to the hills’ is seen, with a sharp reduction in the number of settlements.

The evident peace and security of Crete in the middle and late bronze age may be associated with the emergence of palatial centres, and indeed of a settlement hierarchy. Such a hierarchy can be discerned also in Messenia, and indeed in Euboia during the Late Helladic IIIA and IIIB periods. As Hood, Warren and Cadogan (1965, 52) have written: ‘The general character of settlement in bronze age Crete is beginning to emerge with greater clarity.... Besides the great cities of Knossos, Phaistos and Mallia there were many lesser towns’, some of which at any rate may have had small “palaces”. Outside the towns, the countryside was dotted with farms and villas, isolated or in small groups or hamlets of two or three houses.’ (The terms ‘city’ and ‘town’ should however be read in the light of the remarks above on settlement size.)

Fig. 14.14 shows the major palace centres of Crete, and the villas, as documented by Graham (1962, pl. 1). They are plotted with the modern population centres and transport axes of Crete, on the background of the major cultivated areas. A modern classification of the major sub-regions of Crete is also shown (Allbaugh 1953 [map at rear], for cultivated area; Smith 1966, fig. 1 for sub-regions). Modern villages and the minor late bronze age settlements, which are very numerous, are not shown. The picture which emerges is that in late bronze age times a hierarchy of palaces, villas and smaller settlements was already established which foreshadows strikingly the settlement hierarchy seen in modern Crete.

The systematic hierarchical organisation documented in the records, and illustrated on the map, demanded and brought a measure of peace and internal security. Clearly one of the secrets of Crete’s stable settlement growth was an absence of defensive problems, facilitated by the existence of ample non-coastal arable lands and probably by an adequate control of the sea.

Messenia shared the advantages of ample and rich lands lying some distance from the sea, and out of the way of pirates, so that despite difficulties reflected in the defensive situation of middle bronze age settlements there a continuous growth was achieved.

These two areas, whose development conforms to growth pattern A, were precisely those which in the late bronze age reached the full development of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation as reflected in the palaces of Pylos and Crete. The deduction from this line of reasoning would be that the Argolid, with its palaces at Mycenae and Tiryns, should also conform in its growth to pattern A rather than to pattern B. Future site survey in this area will set the hypothesis to the test.

FIG. 14.14 Settlement hierarchy in prehistoric and modern Crete. The Late Minoan distribution of palaces and villas compares strikingly with that of modern towns and village centres. (The numerous smaller prehistoric sites, and modern small villages are omitted.) Both relate logically to sub-regions and to cultivable land (see notes to the figures).

The regions whose development conforms to growth pattern B did not have the same extensive areas of inland plains as do Messenia and Crete. In Euboia, and the Cyclades in particular, it is difficult ever to be more than a few kilometres from the sea.

Naturally the early bronze age settlements made full use of the sea; the majority at this time were on low promontories, often with a sheltered beach on each side. Good examples of this type of site are seen at Pyrgos in Paros and Aghia Irini in Kea (pl. 14, 2) and at Manika in Euboia (fig. 14.15). Often, as at Pyrgos and Manika, the cemetery lay a little further inland, or sometimes on the steeper slopes of the promontory

Already at this time some of these sites were fortified―Manika, for instance, and Askitario. Troy and Lerna, although not actually on promontories, lie close to the sea, offering similar advantages: they too were fortified (figs. 18.11 and 18.13). In Euboia, significantly, ‘nearly all of the coastal neolithic sites were reoccupied in the Early Helladic period, while the majority of inland sites were never revived’ (Sackett et al 1967, 86). There is a preference for coastal settlements in Laconia also (Waterhouse and Hope Simpson 1961, 168).

Just a few settlements, however, were of acropolis or kastro type, set safely on a high hill, often some way from the sea. The Kastri at Chalandriani in Syros may be used to illustrate this type of acropolis settlement (pl. 14, 1; fig. 14.15) which becomes increasingly popular in the middle bronze age. It does, in fact, lie close to the sea, but the advantages of convenience offered by a promontory location have been sacrificed to those of security ensured by the hilltop situation.

In the middle and late bronze age the number of known settlements decreases markedly. Sites in the Cyclades are now clearly chosen at least as much for their defensibility as for their access to the sea. Rizokastelia in Naxos, for example, is a remote acropolis site of this kind, and Paroikia in Paros is set on top of the sea-cliff. Coastal sites like Aghia Irini and Phylakopi are now defended by massive stone-built walls of a much more substantial character than those of the preceding period (pl. 21.3). Together with the walls of Aegina and Argos they are the true precursors of the Cyclopean walls of the Mycenaean late bronze age.

Some of these settlements are now considerably larger―Phylakopi and Paroikia are examples―and the transition from early bronze age to middle and late bronze age is accompanied by a general increase in size as well as this change in the type of site preferred.

In Euboia the number of settlements is reduced in the middle bronze age, and 15 out of 23 settlements are of the acropolis type. In Laconia too, hill sites were preferred, some of them perhaps fortified, while a number of the smaller Early Helladic settlements were abandoned. In Crete and Messenia, as we have seen, some villages develop into proto-urban and palace centres, and a straightforward hierarchical pattern develops. In the Cyclades, however, the population seems to withdraw, rather, to stronghold centres. These were much larger than the early bronze age villages, and many of the latter were abandoned. Indeed an altogether different settlement pattern develops: each island in general has only one major population centre, sometimes with just a few minor ones as well At the end of the early bronze age, Syros already had the Kastri of Chalandriani, Melos the key township of Phylakopi, and Paros the single settlement of Paroikia. The same general pattern is seen in late bronze age Euboia where it is suggested that ‘there was one main and presumably dominating town to each area’ (Sackett et al 1967, 9).

FIG. 14.15 Two types of settlement in the third millennium Aegean. (Above) the promontory settlement (Manika in Euboia); (below) the hilltop settlement (Kastri near Chaiandriani in Syros). Note the fortifications at each.

What we see happening is something rather different to the development of the prosperous palaces like Pylos or Phaistos. We see anticipated, in a sense, the island city states of classical Greece, where normally each island had a single city centre―just as late bronze age Tenos had Akroterion Gurion, or Paros had Paroikia. Because of their rocky terrain, some islands harboured more than one city state in classical times―Amorgos had three. And it is in these islands, such as Amorgos, that more than one fortified centre may have existed in the late bronze age. Clearly the nature and location of these sites was governed by the need for security.

The chief factor producing these changes in settlement distribution and settlement type may well have been piracy. The words of Thucydides (I, vii-viii, Loeb edition) are highly relevant here, and particularly interesting as possibly the first discussion anywhere of a settlement pattern. He was writing in Classical times, when coastal sites were again favoured, and the ‘older cities’ to which he refers were of the middle and late bronze age:

‘However cities which were founded in more recent times when navigation had at length become safer, and were consequently beginning to have surplus resources, were built right on the sea.... But the older cities, both on the islands and on the mainland, were built more at a distance from the sea on account of the piracy that long prevailed―for the pirates were wont to plunder not only one another but also any others who dwelt on the coast but were not seafaring folk―and even to the present day they lie inland.’

‘Still more addicted to piracy were the islanders.... But when the navy of Minos had been established, navigation between various peoples became safer―for the evildoers of the islands were expelled by him and he proceeded to colonise most of them―and the dwellers of the sea-coast now began to acquire property more than before, and to become more settled in their homes, and some seeing that they were growing richer than before began also to put walls round their cities ... the weaker cities were willing to submit to dependence on the stronger and the more powerful men with their enlarged resources were able to make the lesser cities their subjects. And later on ... they made the expedition against Troy.’

This passage, I believe, contains the key to the understanding not only of the various settlement types, but of the different growth patterns of the time. The nature of the middle bronze age and late bronze age strongholds is explained. The vulnerability of coastal lands and the relative prosperity of inland regions is indicated. The acuity of the problem in the islands is underlined. The advantages of a centralised hierarchical power structure, as in the Minoan civilisation, are brought out. And the development of regional territorial states in Greek times is explained.

It is piracy, a special form of hostility, rather than warring between towns or cities, which can best explain the differences in the prehistoric Aegean growth patterns. The evidence of the fortifications indicates that this had already become a problem in the early bronze age, following the great expansion of settlement and population at that time. The choice of defensible locations for middle bronze age settlements, especially in the islands, followed. The evidence from the Middle Ages, when an analogous situation held in the Aegean, makes this very clear:

‘Piracy has in all ages been the curse of the Aegean, and at this time the corsairs of every nation infested that beautiful sea. Skopelos and Keos, the volcanic bay on Santorin, and the fine harbour of los were favourite lairs of the pirates; they infested the terrible Doro channel between Andros and Euboia, and robbed one of the island barons in the havens of Melos ... the exploits of these men and the terrible devastation which they wrought on the small and more defenceless islands may easily be imagined.’ (Miller 1908, 580)

During the Middle Ages, piracy was practised not only upon passing merchant vessels, but upon any island settlements inadequately defended, nor was it merely the occupation of ruffians of no account, but of lords and barons. Applying this picture to the later bronze age, we may imagine raiding pirates from one island setting out in their long ships to plunder another. Hasluck (1910–11) has documented the terrible mediaeval depopulation when slave raiders and pirates brought about the complete abandonment of several islands. And Miller (1908, 590 and 598), giving further details:

‘We are told at this time that the serfs had fled from Anaphe, Amorgos and Stampalia to Crete because they did not think it worthwhile to sow in order that Turks and Catalans might reap.... At both Naxos and Siphnos there was such a lack of men that many women were unable to find husbands ...at Seriphos, so rich forty years earlier, nothing but calamity: the people passed their lives like brutes and were in constant fear, day and night, lest they should fall into the hands of the Infidels. Syra, destined in modern times to be the most flourishing of all the islands, was then comparatively of no account: the islanders fed on carobs and goats’ flesh and led a life of continual anxiety.... The people of Paros were in the same plight, the principal town of Paroika had few citizens while pirates frequented the big bay at Naoussa. Antiparos and Sikinos were abandoned to eagles and wild asses, and most of the other islets were deserted.’