The early bronze age of Crete, Evans and Mackenzie’s Early Minoan period, shows many striking advances in culture from the rather monotonous picture created by the Cretan neolithic. Metallurgy takes hold and flourishes, the crafts develop dramatically—pottery is attractively painted, beautiful stone bowls are carved from a variety of coloured rocks, and sealstones are minutely worked. These developments doubtless accompanied more basic changes, in settlement pattern and in subsistence, which we are only now dimly beginning to discern. Very significantly, from the standpoint of the archaeologist today, the Early Minoans buried their dead in collective tombs, in cave shelters, built ossuaries, and the so-called tholoi (round tombs of stone) of the great Mesara plain of south Crete. It is from these that the richest finds have come. The period ends with the foundation of the first palaces of Crete at the key sites of Knossos, Phaistos and Mallia. Their appearance marks the beginning of true civilisation in the Aegean (in the sense already defined).

Crete is not only the area of the prehistoric Aegean which has been most intensively explored: it is also the most fully described. Indeed Crete is the only region of the Aegean whose early bronze age has received detailed treatment in previous works. In The Palace of Minos, Evans outlined the Early Minoan period, and the standard works of Pendlebury (1939) and Hutchinson (1962) both devote chapters to it. Excellent monographs on Early Minoan metallurgy and stone vases have recently appeared (Branigan 1968a; Warren 1969b), and Branigan has devoted two books to the culture (1970a; 1970b), while Warren is preparing a detailed study. In consequence, far more is known of the culture than can effectively be set out in a single chapter. The aim here is to focus on the culture sequence, or rather on the phases of development of what was undoubtedly the evolution of a single culture. Specific topics such as settlement pattern, subsistence and metallurgy—in themselves perhaps of greater interest—will be discussed in their general Aegean context in later chapters.

Because of the mixed nature of the finds in the collective tombs, and the sparsity of well-excavated settlements, the Early Minoan period is in some ways a confusing one archaeologically. For that reason it is necessary to define these chronological phases with care. This involves a rather lengthy consideration of pottery styles, which in themselves are of very restricted interest. But the arrangement of the other material, and hence the entire historical reconstruction, must rest upon this basis.

The chronological division of the Early Minoan period was suggested by Mackenzie and Evans in the first decade of the century, following the recognition of this period of the Cretan bronze age as preceding the foundation of the first palaces at Knossos, Phaistos and Mallia, in what was termed the Middle Minoan I period. The division was not set out in full detail, however, until the publication of the first volume of The Palace of Minos in 1921. Nor was it at that time well documented stratigraphically, as Åberg rather forcefully pointed out (1933, IV, 138 f.). He suggested a simple division of Cretan prehistory into Prepalatial, Kamares and Late Minoan periods. This proposal has indeed a pleasing simplicity and has been retained by many subsequent scholars, with the modified terminology prepalatial, protopalatial, neopalatial. Pendlebury (1939, xxxvi) refuted Åberg’s criticisms by instances of the stratigraphic succession at Knossos, but the published accounts of these and other Early Minoan assemblages were not sufficiently detailed to resolve the matter conclusively.

In more recent years Doro Levi has been a consistent critic of the sequence of phases proposed by Evans which, he reports, are not documented by his excavations at the second great palace of Crete, at Phaistos (Levi 1964a, 161; 1964b, 5). The Knossian reply is simply that the site of Phaistos does not adequately document the Early Minoan period. And certainly closed deposits of Early Minoan date are sufficiently abundant elsewhere in Crete to make a long Early Minoan period seem likely.

The root of the problem is that the most important Early Minoan finds (with the exception of the settlements of Vasiliki and Myrtos) are burial deposits—all of them collective, and used over a considerable period of time. Thus, of the important round tombs in the Mesara excavated by Xanthoudides, only three (Salame, Koutsokera and possibly Koumasa tholos A) appear to be without Middle Minoan finds. Some of the ossuaries at Mochlos in east Crete are more homogeneous in content, but such collective deposits, which were not sealed, and were open to the possibility of later internment, are not really a suitable basis for sound stratigraphic discussion.

Several other assemblages -like Miamou (Taramelli 1897), or the various Early Minoan groups at Palaikastro (Bosanquet 1902) are so small that the absence of a particular feature (such as Vasiliki ware) is hardly to be considered significant. And other groups of material, such as the supposed Early Minoan I finds at Mochlos, or the Ellenais house are so briefly illustrated in the publications, if at all, as to be of little practical value (cf. the list of Early Minoan I sites given by Pendlebury, 1939, 55).

Fortunately two recent excavations, at Knossos and Lebena, give categorical stratigraphic evidence for the Early Minoan succession. It is worth quoting extensively from Sinclair Hood’s report of the stratigraphic excavation at Knossos in view of the fundamentally important find of a closed deposit of Early Minoan I pottery in a well:

‘The Early Minoan I well was over ten metres deep with a uniform fill of dark ashy earth and large quantities of pottery, all homogeneous and assignable to Early Minoan I except for a handful of neolithic sherds. At the bottom of the well were remains of large water jugs with plain yellow-brown wiped or scraped surfaces. The rest of this pottery from the fill of the well included fragments of jugs decorated in dark-an-light in the Aghios Onouphrios style and many pieces of high footed bowls with burnished black, grey and red surfaces, and designs in “pattern burnish”. Notably absent were the legs of cooking pots which appear, however, during the subsequent Early Minoan II phase’ (Hood 1963, 92).

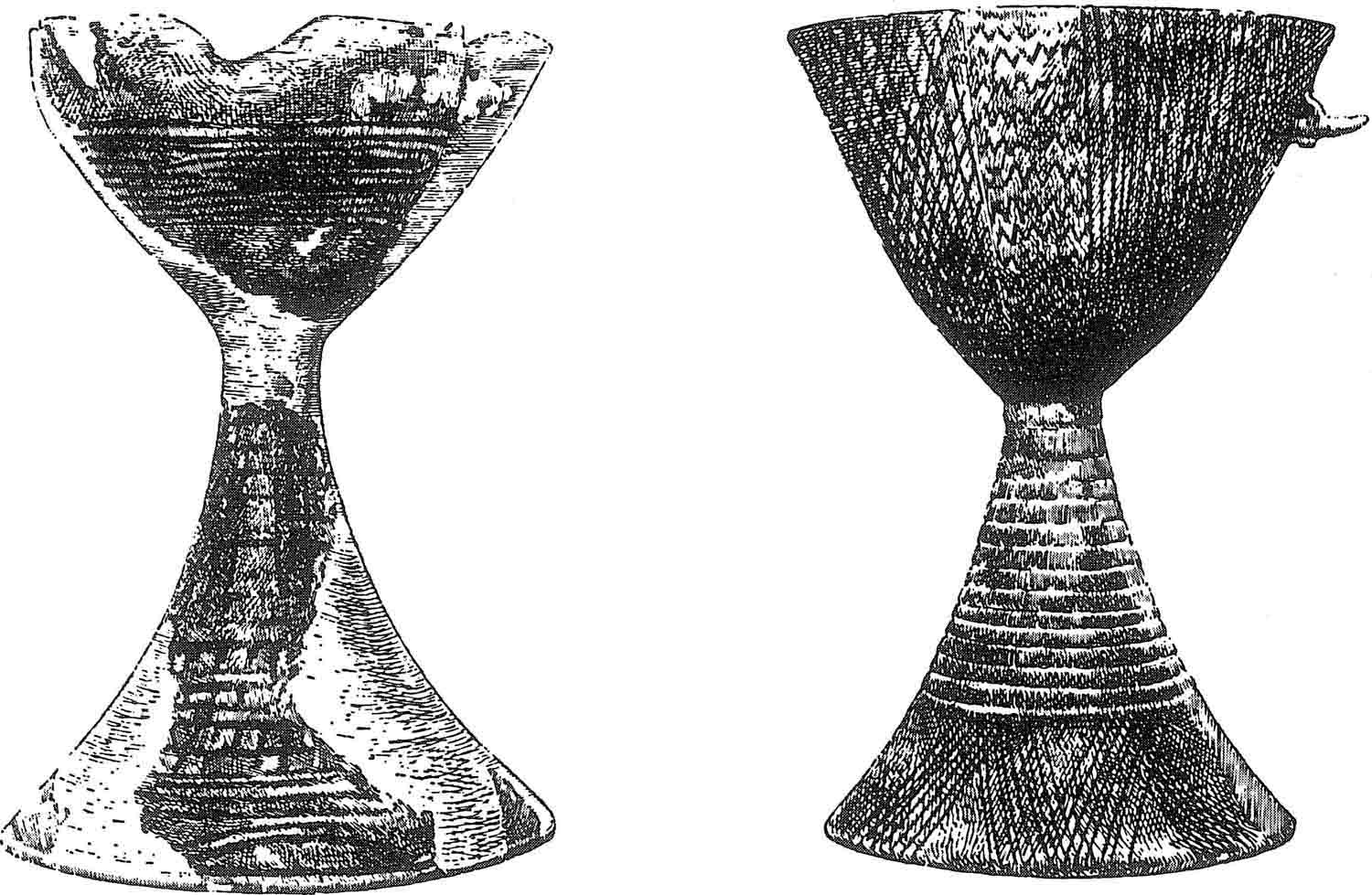

FIG. 6.1 Early Minoan I chalices in the pattern-burnished Pyrgos ware, from the Pyrgos cave (after Evans). Ht c. 20 cm.

Hood goes on to say that Early Minoan II ‘is characterised by goblets on a fairly high foot and by the appearance of the mottled fabric known as Vasiliki ware’. This essential, stratigraphically attested distinction is carried further by Stylianos Alexiou’s important finds at Lebena in south Crete, where one of the round tombs, tomb II, had a pure Early Minoan I level stratified below a level with Early Minoan II and Middle Minoan I material (Alexiou 1958; 1960; 1963).

The very rich finds at Lebena thus allow a more adequate distinction to be made between the pottery of Early Minoan I and Early Minoan II.

The Early Minoan I pottery of Lebena comprises four principal fabrics:

(a) Pattern burnished pottery generally of grey fabric, in what is known as the Pyrgos style after the site of that name (fig. 6.1; Xanthoudides 1918).

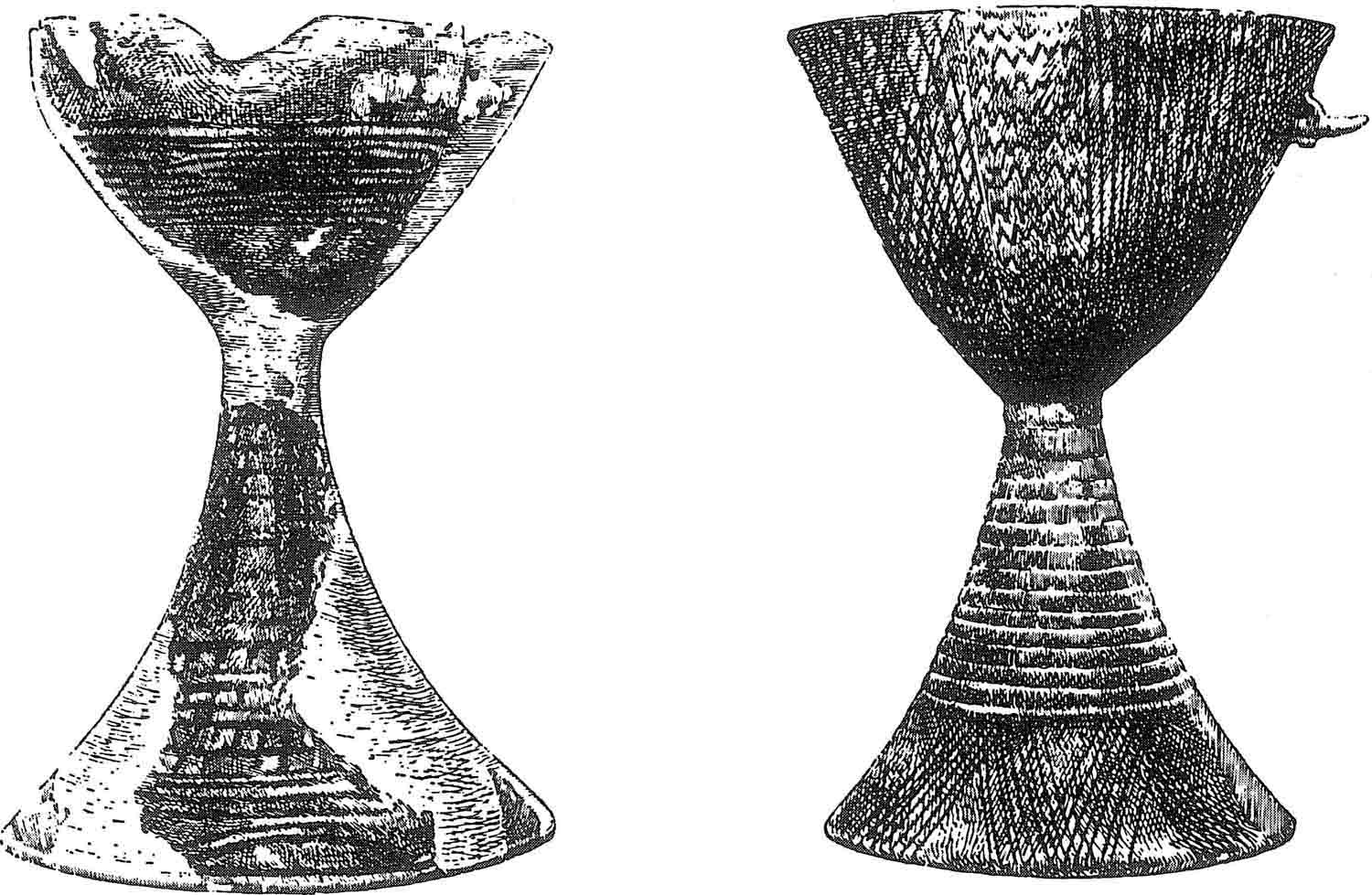

(b) Dark-on-light painted pottery in the Aghios Onouphrios style with red lines on buff or cream ground (fig. 6.2; Evans 1895).

(c) Light-on-dark pottery with designs very like the preceding, the Lebena style.

(d) Plain burnished ware, dark and frequently red in colour.

The principal painted forms are the wide-mouthed jug (Daux 1959, 842, fig. 3; Marinatos 1929), the necked globular jar with two handles (Alexiou 1960, fig. 20; Xanthoudides 1918, fig. 6), the broad one-handled cup (Daux 1959, 842, fig. 4; Alexiou 1951, pl. IΔ’, fig. 2), and the pyxis standing on three feet and with a deep-sided lid (Alexiou 1960). In the pattern-burnished Pyrgos ware, tall chalices are common (at Pyrgos and Arkalochori) and three-footed cylindrical pyxides are found at Lebena. The footed askos is found at Lebena, as at the site of Kanli Kastelli, and animal vases are common.

It is clear, therefore, that the distinctive innovations in the pottery of the Early Minoan I period are the introduction of painted decoration (both dark-on-light and light-on-dark) and of the jug. An interesting feature at Lebena is the almost complete absence of incised ware from the Early Minoan I material. It almost looks as if incised decoration (which is rare in the final neolithic) declined in Early Minoan I before appearing in quantity early in Early Minoan II, and incision should not necessarily be regarded as an important element of continuity between neolithic and Early Minoan. Other features show continuity with the preceding final neolithic as discussed in chapter 5, In particular pattern-burnished ware occurs already in neolithic deposits (Levi 1961–62, fig. 132; Evans 1921–35, II, fig. 3m, and fig. 4), while a typically final-neolithic homed suspension pot was found in the Early Minoan I deposit at Lebena (Alexiou 1960, fig. 10; compare Tod 1902, 341, fig. 1).

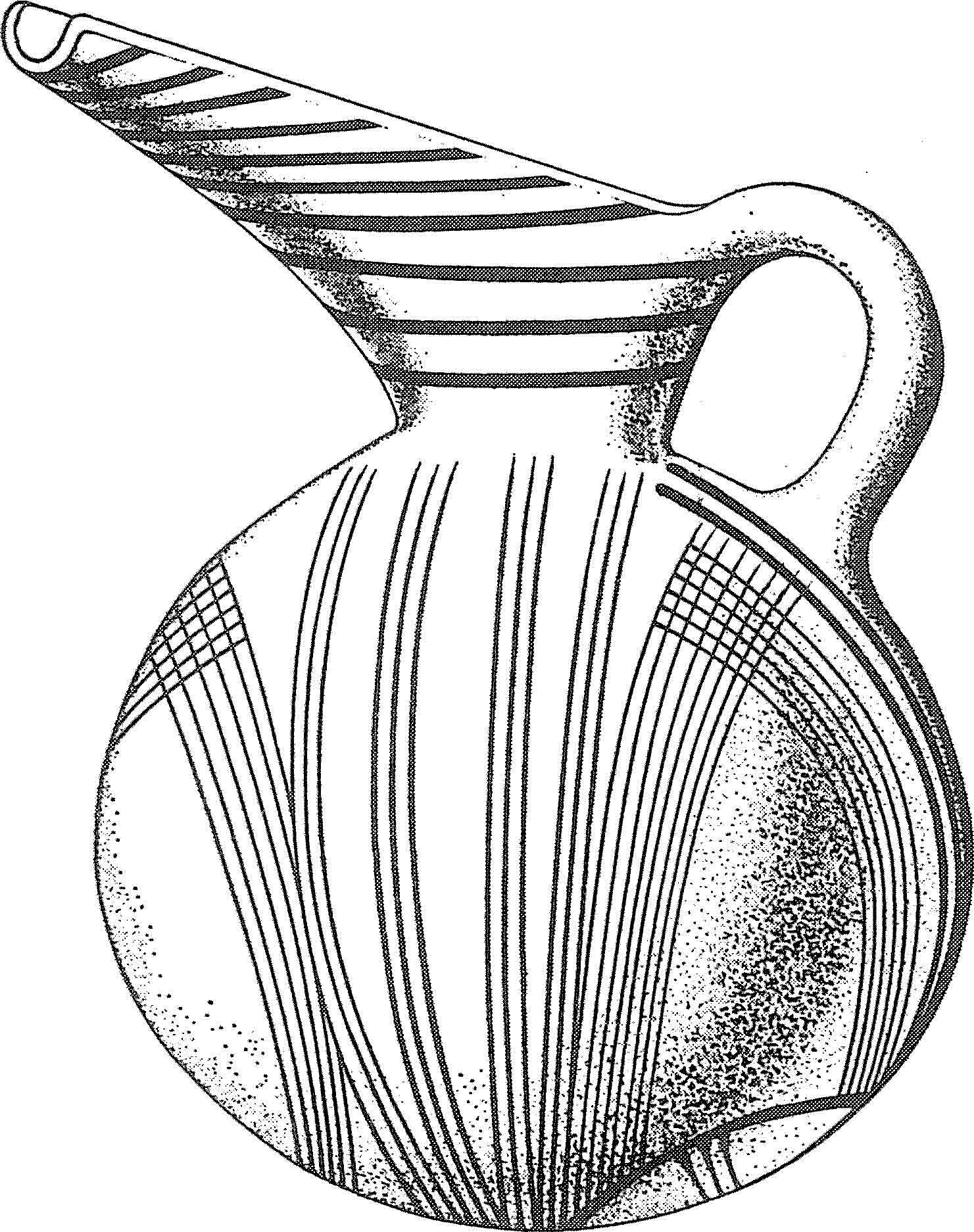

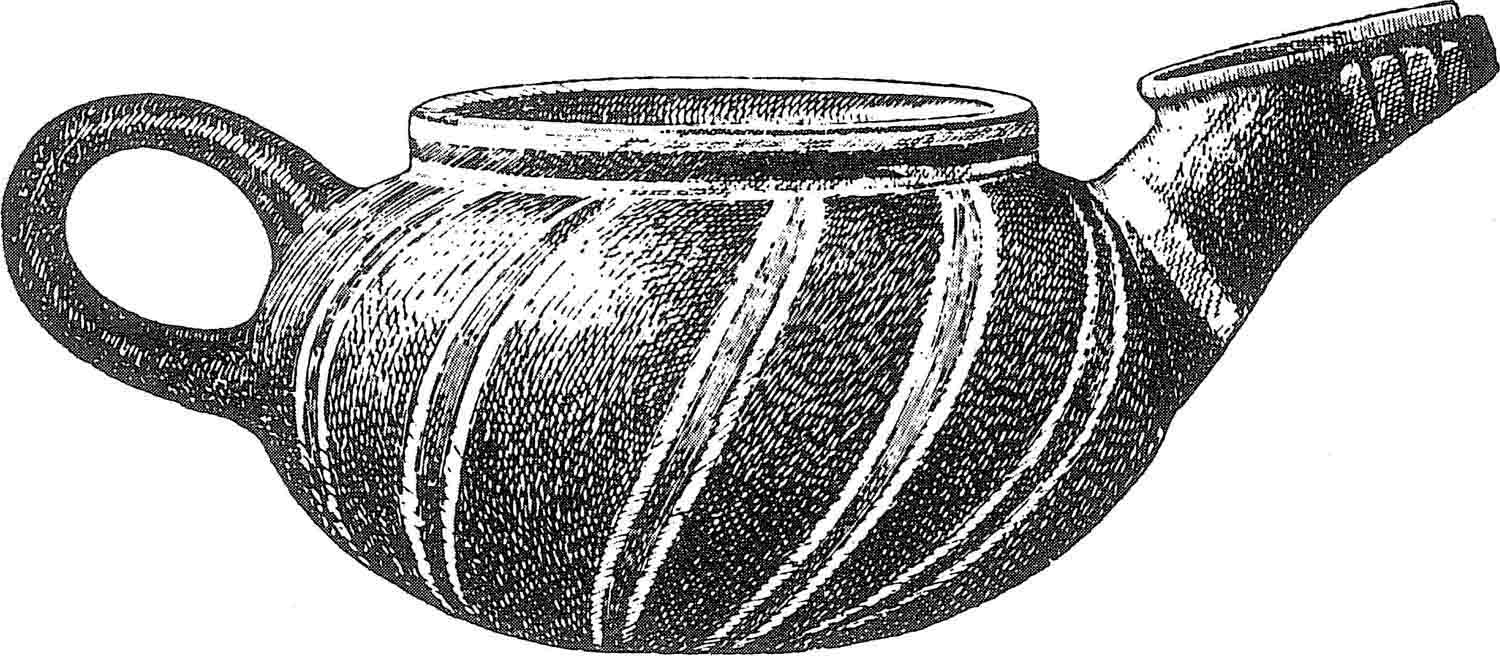

Turning now to the features which separate the Early Minoan I and Early Minoan II assemblages from each other, we find the chief change is in the introduction of the mottled Vasiliki ware (Marinatos and Hirmer 1960, pl. III) this may be taken as the defining innovation for the Early Minoan II period, just as the appearance of Aghios Onouphrios ware marked the inception of Early Minoan I. Spouted shapes, notably the beaked jug and the teapot develop; spherical pyxides are found, and incised decoration, often in the form of concentric circles, occurs. On the basis of the Lebena finds it seems that pattern-burnish decoration becomes very much rarer, although apparently it does not entirely disappear.

Unfortunately, this definition, which is in accord with the finds at Lebena, the Knossos well, Myrtos and Vasiliki, at once raises difficulties on certain other sites. Neither the Pyrgos Cave or the Kanli Kastelli shelter contain Vasiliki ware, although both are rich in Early Minoan I ceramic finds. A strict application of the criterion would make both Early Minoan I in their entirety. Yet the Pyrgos Cave contains long daggers as well as a folded-arm figurine (Xanthoudides 1918, fig. 15) which some authors would prefer to see as Early Minoan II in date. And Kanli Kastelli likewise has these long daggers.

It is perhaps largely this difficulty which has led some authors such as Hutchinson (1962, 141), Branigan (1968a, 58) and Warren (1965) to use the terms Early Minoan Ha and Early Minoan lib, sometimes without rigorous definition. Only at Vasiliki have the Early Minoan II levels been given a plausible stratigraphic division. Hutchinson suggests that in the Early Minoan Ha period, Vasiliki ware was restricted to east Crete, being adopted in central Crete in the lib phase. This suggestion—which again highlights the inadequacy of the periodic system of nomenclature when applied to a cultural assemblage rather than simply to a division of time—leaves the Early Minoan Ha assemblage undefined. Warren has been more explicit, stating ‘there is no hard and fast line between Early Minoan I and Early Minoan II’ (1965, 19). He further clarifies: ‘Early Minoan Ha is that period, definable by the stratigraphic sequences, where mottled Vasiliki ware occurs but has not yet assumed full domination’, but he goes on to class as Early Minoan IIa, assemblages where Vasiliki ware apparently does not in fact occur, for example the early ossuary at Palaikastro. Two of his defining Early Minoan Ha shapes—the lentoid pyxis and the cylindrical pyxis on three feet—occur already in the Early Minoan I deposit at Lebena and continue later.

FIG. 6.2 Early Minoan I jug in the dark-on-light painted Aghios Onouphrios ware, from Aghios Onouphrios (after Evans). Ht c. 21 cm.

One problem here is the incised ware: at least four decorative styles are seen, most commonly on a fine grey fabric.

(a) Heavy incision, common at Pyrgos. Applied to cylindrical and conical pyxides (Xanthoudides 1912, fig. 9, 62–65 and pl. III) and other shapes. The vessels are often rather crudely made, brown in colour and thicker than the other incised fabrics. This style was classed by Pendlebury as Early Minoan III (1939, 85 and pl. XIII, a–c).

(b) Fine incision, utilising concentric circles (Xanthoudides 1924, pl. I, 4191; Taramelli 1897, fig. 15). Commonest at Lebena in the Early Minoan II levels. Applied often to spherical pyxides or neck jars.

(c) Fine incision of oblique parallel lines, possibly combined with decoration of type (b). Applied often to spherical pyxides (Xanthoudides 1924, pl. I, 4188 and 4194; pl XVIII, 4195 and 4196).

(d) Excision, seen occasionally on spherical jars (Dawkins 1904–5, 290).

At the moment pottery of these classes may well belong exclusively to the Early Minoan II period, perhaps the earlier part of it, but it would be wrong to be dogmatic. It Is, in the absence of quantitative analyses of the ceramic assemblages, very difficult to define a clear boundary between Early Minoan I and Early Minoan II. At present it may be simplest to designate apparently mixed deposits such as those of Kanli Kastelli and Pyrgos simply ‘Early Minoan I–II’ to emphasise that the distinction remains in many of the collective burials an uncertain one.

The beginning of the Early Minoan II period is thus established for us through the definition of Early Minoan I at Lebena and the Knossos well. Vasiliki ware with accompanying new forms appears, patterned-burnish ware declines markedly and at Lebena, at least, incised ware becomes more common.

To define the later end of Early Minoan II is a still more difficult problem, which involves us immediately with the definition and indeed the very existence of the so-called Early Minoan III phase. In 1939 Pendlebury wrote:

‘The Early Minoan III period is a curious and difficult one to define for, as we shall see, it can in some ways be called transitional between the Early and Middle Bronze Ages in Crete, yet at the same time it has features of its own in the east and south which mark it off as a new epoch, while in the centre and north it is very clearly the end of the archaic Minoan period’ (p. 78). He went on, ‘The great difference between the pottery and that which has gone before is the substitution of light-on-dark for dark-on-light decoration’ (p. 80). The Lebena finds make clear that in the Mesara area at least, light-on-dark decoration is found in the Early Minoan I and Early Minoan II periods, and the presence of this technique alone cannot be considered conclusive.

Hood’s Knossos report is very relevant here, and again should be quoted in extenso:

‘The Middle Minoan Ia period is characterised by goblets on a low foot, in shape like a modern egg-cup but larger, Early Minoan III, as this was defined by Evans, does not seem to exist at Knossos. Evans himself never identified a pure Early Minoan III deposit with characteristic features at Knossos, and he defined the period in terms of stray finds from Knossos itself, and of deposits from other sites in the east of Crete. It looks very much as If the material which Evans grouped as Early Minoan III is contemporary with his Middle Minoan la at Knossos, and some of his Early Minoan III material may be even later, contemporary with Knossian Middle Minoan Ib or even Middle Minoan II.

On the other hand the Middle Minoan Ia material is vast in quantity. It probably covers quite a long period of time, and is capable of sub-division. In the earliest phase there appears to be no trace of polychrome decoration. This pre-polychrome phase might therefore be called Early Minoan III and it may be this phase that Evans meant by Early Minoan III itself’ (Hood 1963, 93). This phase, prior to the introduction of polychrome ware, will, following Evans, be designated Early Minoan III in Hood’s forthcoming Knossos report.

FIG. 6.3 ‘Teapot’ from Knossos with polychrome decoration, assigned by Evans to the ‘Early Minoan III’ period. Red stripes with white borders on dark ground (after Evans). Ht c. 9 cm.

The Lebena finds give a similar picture. In tomb Ha (adjacent to tomb II) a sand layer separated a pure Early Minoan II deposit from the overlying Middle Minoan la one. And elsewhere the Early Minoan II burials were followed immediately, it seems, with grave goods of Middle Minoan la type. Alexiou concluded (1963, 90), ‘The Early Minoan III period is absent, and as Evans himself suggested (1921–35, I, 164) must correctly be considered as a Middle Minoan I style of eastern Crete.’

This pertinent observation raises again the question of regional differentiation within the Early Minoan period, and a clear picture of these chronological phases will emerge only when this aspect of the problem is tackled. At present, then, chronological subdivisions within the Early Minoan II period (as well as the definition of ‘Early Minoan III’) must at present rest on rather doubtful typological grounds. It seems likely that valid stratigraphic distinctions will yet be made within the Early Minoan II period. But the onus is upon those who will make them to document them fully and convincingly.

The Early Minoan I period is defined, as we have seen, on the basis of new pottery shapes and fabrics (figs. 6.1–6.2) but its importance lies in the new settlement pattern now emerging, and in the changes, now only dimly hinted at in the archaeological record, which are seen much more clearly in the Early Minoan II period. The comments here will be restricted to a brief review of the evidence: discussion of the underlying changes taking place is deferred to Part II.

There are so far no extensively excavated settlements of the Early Minoan I period. The well at Knossos, already cited, has yielded valuable stratigraphic evidence, but there are no house plans from that site. The scanty and virtually unpublished remains at Mochlos and Ellenais Amariou establish merely that rectangular houses were still in use. It seems likely that the neolithic agglomerate plan seen already at Knossos, which is repeated at Early Minoan II Vasiliki, was prevalent also during the Early Minoan I period. A house at Phaistos, possibly of this date, had a floor decorated with red stucco, and a circular hut of final neolithic or Early Minoan I date has recently been found there.

Most of the known Early Minoan I material comes from burials. The tradition of burial in caves and rock shelters, seen already in the final neolithic, persisted and the finds at Pyrgos and Kanli Kastelli are among the most important of the period. The great innovation at this time, however, was the inception of the built tomb used as an ossuary or for collective burial. At Lebena (Gerokambos) in the Mesara Plain a circular tomb was found with well stratified Early Minoan I grave goods, and several other tholos tombs were apparently built at this time. Branigan (1970b, 22) suggests that at least twenty-two were built in the Early Minoan I period, as against seven in Early Minoan II and fourteen in Middle Minoan I. They are circular in plan, generally between 3 and 10 m in diameter, with an entrance at the east side. The walls, which sometimes reached a height of at least 2 m, were of large, roughly dressed stones, bonded with clay. Although it was thought by Xanthoudides that they were vaulted in tholos construction, it seems more likely that they had a simple brushwood roof, perhaps weighted down with stones which have (for instance at Lebena II and Kamilari) been found packed together, as a result of the roofs collapse, on the floor of the tomb.

Another possibility is that they were roofed with mud-brick vaults, resting on the stone walls which are all that now remain.

At this time the grave goods were predominantly of pottery. At Lebena there are no stone bowls in the Early Minoan I levels, and the obvious implication is that stone bowls were not at that time manufactured in Crete (Warren 1965, 8). There is other evidence to suggest that stone bowls were imported already from Egypt by this time.

Sealstones are likewise not found at Lebena in the early deposits, and this may lead to a similar conclusion. On the other hand, the products of Early Minoan I craftsmen were not necessarily all represented among the grave goods of the lowest levels of tomb II at Lebena. In Warren’s extensive excavations at the important Early Minoan II settlement at Phournou Koriphi, Myrtos near Hierapetra (Warren 1968) only three sealstones were found, and metal was represented by a dagger blade—yet this does not prevent our concluding that metallurgy and the glyptic arts were well developed by the end of the Early Minoan II period. In the same way it is possible that the Early Minoan I crafts were more developed than the finds have so far indicated.

Again no metal has been found in undoubted Early Minoan I deposits. A scrap of copper found by Seager (1912, 93) at Mochlos is the only possible exception. But the copper axe from neolithic levels at Knossos (fig. 16.2) is a reminder that copper was already known (Evans 1921–35, IV, 4 and fig. 3, f.) and there is no reason to suppose that this acquaintance diminished. On the contrary, Branigan in his detailed study (1968a, 54) while conceding that ‘no copper objects have been found in pure Early Minoan I deposits’ underlines the significance of the Pyrgos and Kanli Kastelli metal finds, chiefly daggers and awls, and concludes that these types and several others were probably already manufactured in Early Minoan I times.

Figurines were certainly made: in the first place there are pottery finds of animals at Lebena. Tomb II at Lebena yielded also a marble (or encrusted limestone) figurine of schematic figure-of-eight shape (cf. Evans 1895, fig. 124), and it may well be that the rather shapeless and schematic figurines from Pyrgos (Xanthoudides 1918, fig. 14) are datable to Early Minoan I. The typically Cretan variant of the marble schematic figurine, the Aghios Onouphrios type (fig. 19.4; Renfrew 1969a, 27) may also date from this period. The most significant feature of all these finds, however, is that they are from burials. And while the Early Minoan I burials in the Pyrgos Cave follow the final neolithic tradition (seen at Eileithyia and Partira) the round tombs at Krasi and Lebena are the beginning of a new and influential tradition in Crete.

The overseas connections of Early Minoan I fall apparently into two classes. First are those forms which show a relationship with pottery of the Grotta-Pelos culture of the Cyclades, which are discussed below with that material. Secondly there are similarities with the west Anatolian cultures, especially Troy I, which have recently been emphasised by Warren. These are mentioned again in chapter 20. There are no convincing links with mainland Greece. Nothing in the Early Minoan I levels unequivocally indicates contact with Egypt or the Near East, although the possibility of influence from the Ghassulian culture of Palestine has been advanced. We should bear in mind that two Predynastic or Early Dynastic Egyptian stone bowls (cf. fig. 20.2) were found in a late neolithic house at Knossos, and so some contact with Egypt had already been established (Warren 1965, 30–31, nos. 5 and 13).

The Early Minoan II period clearly shows a dynamic expansion and development in the life of prehistoric Crete. There is a risk, however, of exaggerating this striking change by assimilating to Early Minoan II all the finds which have previously been termed ‘Early Minoan III’, some of which may as plausibly be ascribed to Middle Minoan I. Few of the rich tombs at Mochlos were without Middle Minoan I objects, or ‘Early Minoan III’ objects which might now be given a Middle Minoan I date. Tombs I, II, VI (lower), XIX and perhaps XXI do, however, essentially antedate the middle bronze age, and show already the impressive gold diadems and jewellery which at Lebena are seen in the Middle Minoan I level.

More settlement sites are known for the Early Minoan II period than for the preceding Early Minoan I: Warren has stated that fifty-four open sites are known and twenty-two cave sites. Two of these settlements, Vasiliki and Phournou Koriphi near Myrtos, both in east Crete, have been excavated. Together they give a vivid impression of proto-urban settlement in mid third millennium Crete.

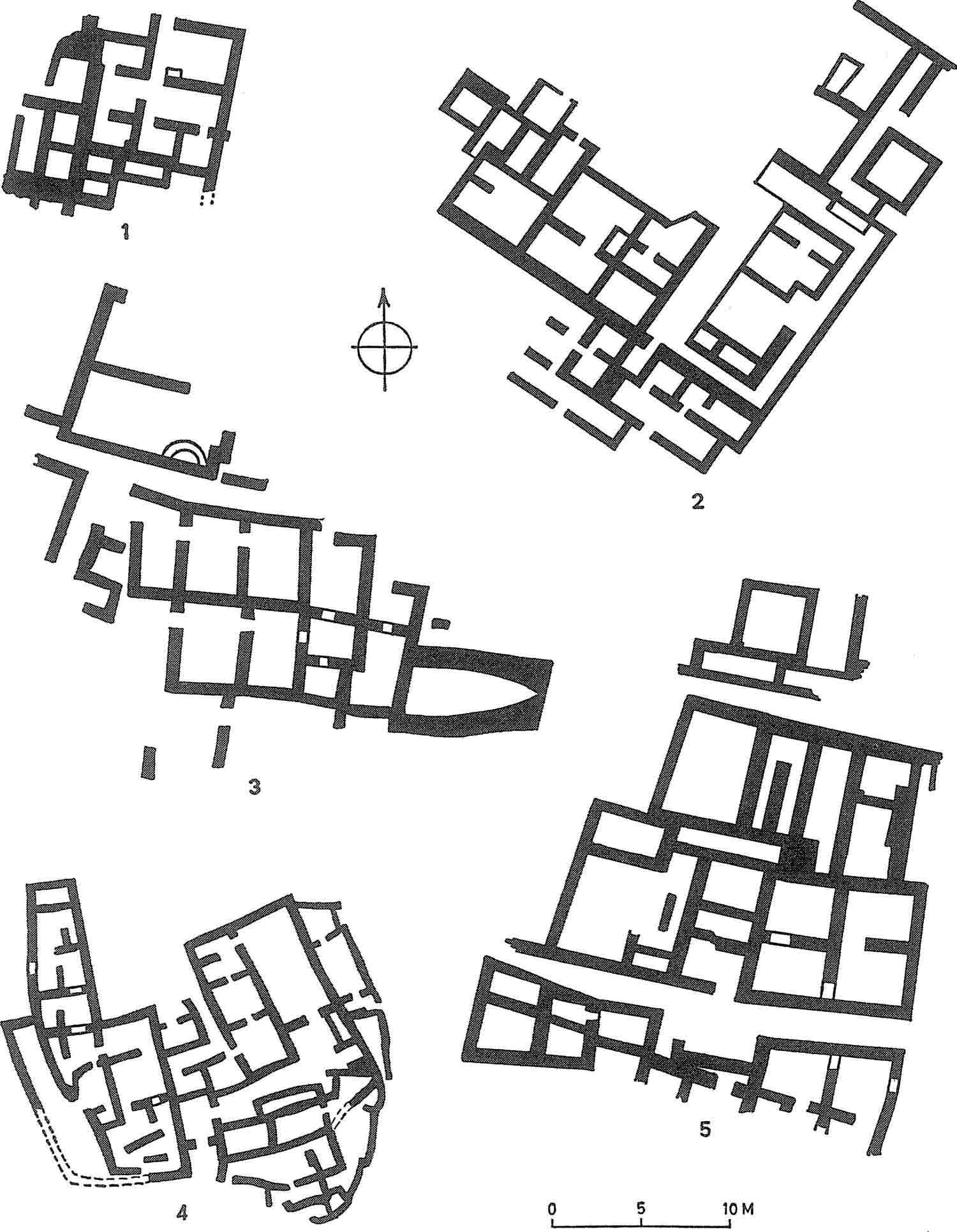

At Vasiliki building remains are of two phases. Those of the later phase are by far the more impressive (fig. 6.4, 2). The published plan shows a carefully laid-out building complex, more than 30 m long, with regular rectangular rooms. Construction was of timber-laced mud brick, together with plastered clay (Boyd Hawes 1908). On the one hand, in looking at this plan, one recalls the similarly agglomerate nature of the house in the final neolithic deposits at Knossos (fig. 6.4, 1). And on the other hand the complex of rooms is a forerunner of that seen in the stone-built palaces of the Middle Minoan period some centuries later (fig. 4.4). A considerable quantity of pottery was found, including much of the brown mottled ware now termed ‘Vasiliki ware’, which is a characteristic feature of Early Minoan II. Although some writers regard this ‘house-on-the-hilltop’ at Vasiliki as a ‘mansion’ —implying the existence of many smaller houses in the village—a different interpretation seems more plausible. This house at Vasiliki may itself constitute much or all of the village there, a village on the agglomerate plan like Çatal Hüyük in the Anatolian early neolithic or Dhimini in the Thessalian late neolithic.

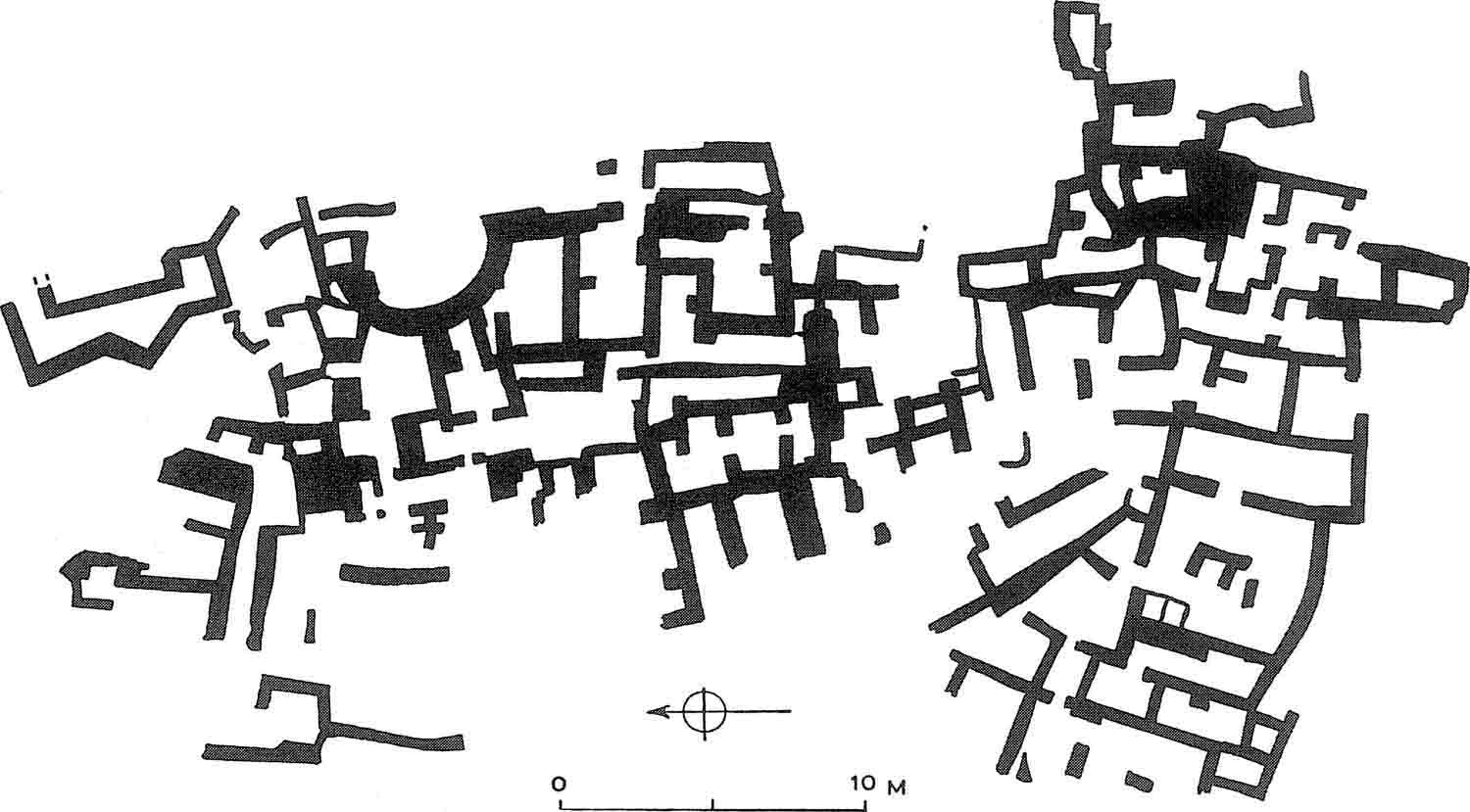

This view is strengthened by Warren’s important finds at Myrtos (Phournou Koriphi). A small village (fig. 6.5) was found there on the summit of a low hill overlooking the southern coast of Crete. Partly because of the irregular terrain, perhaps, the plan of this village is much less regular than at Vasiliki. The foundations of the walls are of stone, their upper parts of mud brick, and they were sometimes decorated with red painted plaster. The rooms are in principle rectangular, although their shapes are, in fact, irregular. On the south side, on the cliff edge and indeed partially eroded, was a semi-circular stretch of wall. Again, therefore, we see a village on the agglomerate plan.1 A complex of rooms at the north side of the summit area contained a large spouted tub and channels for drainage, and the excavator suggests that this area may have been used for the fulling and dyeing of textiles.

FIG. 6.4House blocks of the early Aegean, shown at the same scale.

1. Late neolithic House A at Knossos;

2. Early Minoan II ‘House on the Hilltop’ at Vasiliki;

3. Buildings of the Korakou culture (‘Early Helladic ll’) at Aghios Kosmas;

4. Insula VIII of the Troy II period at Poliochni in Lemnos;

5. Street and houses of the Second City at Phylakopi in Melos.

More than 250 complete vases were found, together with a range of domestic tools in stone and clay. A copper dagger was recovered, and three sealstones, as well as sealings (seal impressions) in clay—finds of considerable significance which are discussed again in Part II. The seals may have been carved at the site itself. Clay figurines were also found.

FIG. 6.5 Plan of the stone walls and foundations of the Early Minoan II settlement at Phournou Koriphi, Myrtos (based on plan by Minto, by kind permission of the excavator Dr P. M. Warren).

The site belongs to a single phase of occupation, late in the Early Minoan II period, but probably prior to the east Cretan ‘Early Minoan III’, since no white-painted ware was found. The site was destroyed by fire, and radiocarbon determinations for the destruction have been made: 2192 BC, 1855 BC, and 1785 BC (Q953: 950 and 951) in radiocarbon years, giving a mean of 1910 BC. This suggests a date in calendar years for the destruction, of between 2600 and 2100 BC. Probably the destruction took place about 2200 BC.

The information gleaned from these very important sites is supplemented by others, such as Palaikastro and Knossos, where the finds are more scanty. The main source of our knowledge of the material culture of the Early Minoan period comes, however, from tombs. In southern Crete especially, the round tombs of Mesara type (fig. 19.11) were in intensive use: those built in the Early Minoan I period continued, several more being added. In consequence, the basic publication of Xanthoudides is a major source for information of the principal classes of Early Minoan II craftsmanship (see Xanthoudides 1924 and Branigan 1970b).

Cave burial continued, as some finds, probably of Early Minoan II date at Pyrgos, indicate. And rectangular built ossuaries, especially in east Crete, are now common. The most important of these, with regular rectangular rooms, were at Mochlos, where a whole series was excavated by Seager (1912, fig. 16.7) yielding rich grave goods. Similar ossuaries have been found at Palaikastro, Gournia and Archanes in central Crete. Another variety, square in plan and divided into long, narrow parallel chambers, is also seen at Palaikastro.

At the end of the period, at the time designated ‘Early Minoan III’ by some writers, two new burial forms are seen. The first involves burial in a large clay coffin or larnax. Twenty of these were found in the Pyrgos Cave, measuring up to 1 m 20 cm in length, and in the shape of elongated ellipses (Xanthoudides 1918, 138 and 140–42). These may be the ancestors of the splendid painted larnakes of the Late Minoan period. Burial in large jars or pithoi are also seen, notably at Pachyammos in eastern Crete, where a cemetery of pithos burials was found (Seager 1916).

These various settlement and burial sites have yielded the abundant finds which build up the picture we have of the Early Minoan II period.

The material finds of the Early Minoan II period, thanks principally to the profuse grave goods in the Mesara round tombs and the rectangular ossuaries, are particularly abundant. This phase of the Early Minoan culture is, in consequence, better documented than any other of the third millennium Aegean. Many aspects of this material are considered in Part II.

The pottery fabrics and shapes which serve to define Early Minoan II (with Early Minoan III) have been discussed already. In general the painted ware of Early Minoan Crete contrasts strikingly with the dull monochrome of Cretan neolithic. Among the shapes, vessels for drinking and pouring are well represented.

The splendid stone vase production, one of the most striking features of Early Minoan art, now began. The earliest are a group of vessels in chlorite schist, often decorated with incisions (fig. 6.6, Warren 1965). In the later part of the Early Minoan period a wide variety of stones was employed, in a considerable range of shapes. Prominent among these was the ‘block vase’, of rectangular form with a series of holes cut to make a multi-compartmented receptacle. The development of this typically Minoan industry has recently been set out in detail (Warren 1969b).

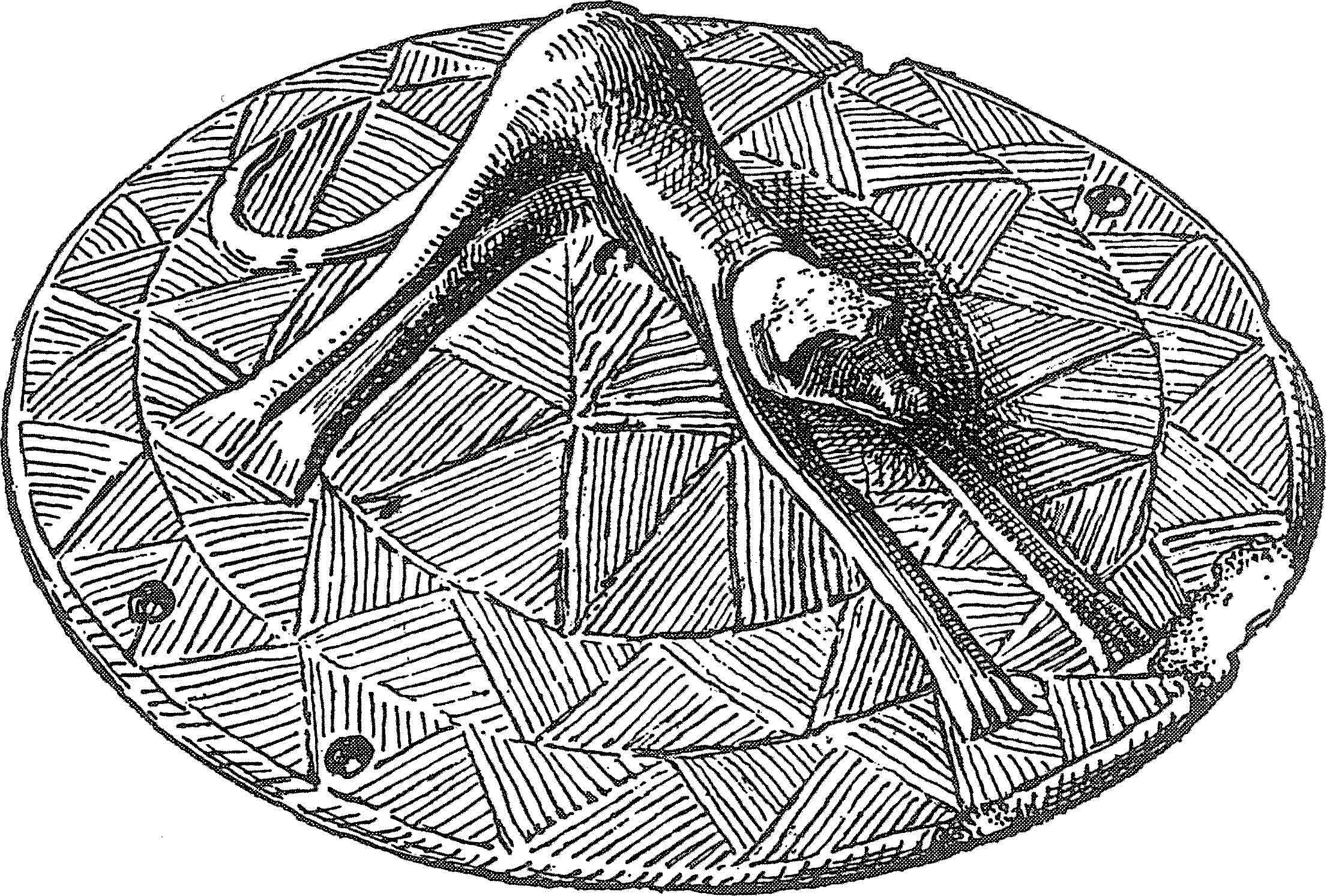

At the same time the sculptural ability of the Early Minoan craftsmen is reflected in a splendid series of sealstones, whose first manufacture dates apparently from the Early Minoan II period (fig. 6.7; Matz 1928; Kenna 1960). Many fine examples from the Mesara tombs are illustrated by Xanthoudides (1924).

Figurines of several forms are now seen, including vases of animal and human form (e.g. Fig. 19.8; Pendlebury and Money-Coutts 1936, pl. 13). The very simple schematic figurines of marble, most notably the Aghios Onouphrios type (fig. 19.4) are still made, and folded-arm figurines imported from the Cyclades. Soon they were copied in Crete, and the local sculptors produced a recognisable type: the Koumasa variety (pl. 30, 3, 4 and 6; Renfrew 1969a, 18). A further series of figurines of stone is rather less sophisticated in execution (cf. Pendlebury and Money-Coutts 1936, pl. 18).

FIG. 6.6 Incised pyxis lid of chlorite schist, from tomb I at Mochlos. Diam. 11 cm (after Seager).

The most important and striking development in the Early Minoan II period is the rapid growth of metallurgy. As discussed in chapter 16 the antecedents for this development may be discerned earlier, but it is now that the daggers of copper and bronze were made in greatest numbers, and jewellery and adornments, some of them very beautiful (fig. 6.8; pl. 18, 4) were made in gold and other metals. Metal tools are surprisingly rare in Early Minoan Crete, but the quantity of daggers found in the collective tombs is very striking.

The overseas connections of Early Minoan II are more numerous than those of Early Minoan I. Some of the Cycladic ones, notably the figurines, are considered in the discussion of the Keros-Syros culture in chapter 11 and the relationships in metal working in chapter 16. The important contact with the Near East documented chiefly by finds of ivory, are mentioned in chapter 20. The only clear Indication of contact with mainland Greece, other than the apparently Minoan seal from Aghios Kosmas (Mylonas 1959, fig. 166, 13) is given by the important finds at Kastri on Kythera (Coldstream 1970), although mention should be made also of a little jug from Boeotia (Sotiriades 1908, fig. 13) which has Cretan resemblances (cf. Seager 1912, fig. 13, and the butterflies on the dish) but may in any case be of Middle Helladic date. At the hillock of Kastraki near Kastri on Kythera, a rubbish pit was found containing material of the Eutresis and Korakou cultures. This settlement was followed by the Early Minoan II occupation of the site of Kastri itself. There are undoubted finds there of Early Minoan II—III pottery, and a marble jug from Kythera probably comes from this site (Wolters 1891, 53). Kastri in Kythera can be regarded as a Minoan colony, the first of several sites to show signs of Minoan presence during the bronze age.

FIG. 6.7 Ivory seals of Early and Middle Minoan date from the larger tholos tomb at Platanos in the Mesara plain (after Evans). Scale c. 1: 1.

FIG. 6.8 Early Minoan gold jewellery from tomb II at Mochlos (after Seager). Scale c. 2:3.

The early bronze age of Crete is brought to an end by the foundation of the first palaces. At Knossos and Mallia, pottery formerly designated Middle Minoan la is found: Phaistos may have been founded a little later (Pendlebury 1939, 97). The clarification and more precise definition of terminology for the end of the Early Minoan and beginning of the Middle Minoan periods may soon be undertaken by Hood. Meanwhile the conventional usage will be followed. The plan of the later palace at Mallia supposedly follows closely that of the first foundation (fig. 4.4). A schematic plan is available also for the Middle Minoan palace at Knossos. Clearly most of the features seen in the later palaces, including the provision of copious storage facilities, were already present.

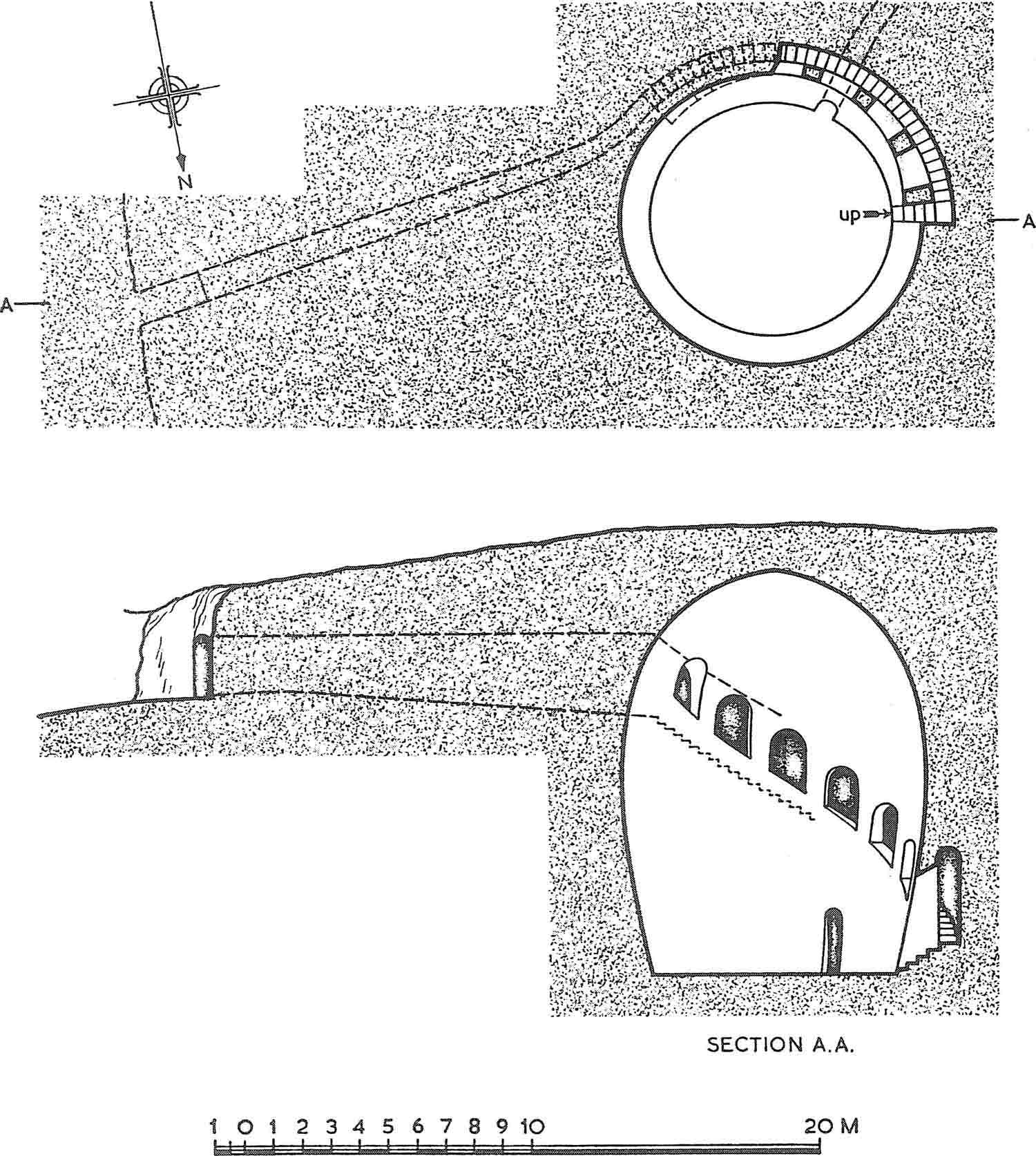

Mention should be made here of the remarkable hypogeum at Knossos (fig. 6.9), which was apparently constructed before the first palace there, and may belong to the ‘Early Minoan III’ period. A large underground chamber, dome-shaped, and with a staircase leading down from the top, it may have been used as a granary.

FIG. 6.9 The hypogeum at Knossos, which may have served as a granary, and was assigned by Evans to the Early Minoan III period (after Evans).

The continuity in the transition from prepalatial to protopalatial Crete must be emphasised. The significance of Vasiliki and Myrtos as proto-urban settlements has already been indicated. There is continuity in burial too—Chrysolakkos, the rich ossuary of the First Palace at Mallia, is simply a development from the Early Minoan ossuaries. Burial in rock-cut tombs is, however, a new feature in Crete in the Middle Minoan period. There is great continuity also in technology and craft.

With the establishment of the first palaces in Crete, phase IV in our developmental scheme, the period of the development of proto-urban communities comes to an end. Crete henceforward is the home of a civilisation. But during phase IV, developmental analogies to those seen in Crete occur elsewhere in the Aegean. It is necessary, therefore, to establish the culture sequence in these areas before considering the processes at work.

1 I am particularly grateful to Dr Warren for permitting the inclusion here, in advance o f publication elsewhere, of a sketch plan of Myrtos, which is based on the detailed large-scale plan of the site drawn by Mr Ken Minto for Dr Warren, to appear in the final excavation report.