Reason is a very inadequate term with which to comprehend the forms of man’s cultural life in all their richness and variety. Hence, instead of defining man as an animal rationale, we should define him as an animal symbolicum. By so doing we can designate his specific difference, and we can understand the new way open to man—the way to civilisation.

ERNST CASSIRER (1944, 26)

Go, go, go, said the bird: humankind

Cannot bear very much reality

T. S. ELIOT, BURNT NORTON

When the archaeologist seeks a definition for man, he usually turns pragmatically to the notion homo faber, man the toolmaker. The concept is certainly a workable one archaeologically, for only the material record of man’s past survives, and to choose this very record as a defining feature is to make the best of the available evidence.

But no one takes this definition too seriously: no one is very surprised to learn that the other modern primates sometimes make tools. Everyone is aware that the most fundamental distinction must lie in a different sphere—in the way man thinks. It is indeed difficult to have knowledge of other minds otherwise than through the behaviour of other people, and the quality of thought is too personal an attribute to form the basis of a working definition for the archaeologist. Yet many of man’s abilities and behaviour patterns seem to spring from his self-consciousness: from his self-awareness in the world, and from his acute awareness of his place in the world.

By his ability to see himself he is enabled also to see the world more clearly. He builds for himself, indeed, a picture of the world which embodies his observations and beliefs. Every man has such a world-picture, such a Weltanschauung. By permitting him to visualise, to imagine, it enables him to reason about the future as well as the past, to consider alternatives, to make plans. It facilitates, too, far more than coolly rational thinking. Man, more keenly aware of the world, is cognisant now of its mysteries and of its dangers. Death, something which he has seen and remembered, finds a place in the world-picture, as well as pleasure, sorrow and fear. These too become matters for contemplation and for action.

In all his actions, other than purely reflex actions, a man responds as much to his picture of the world as in direct and immediate response to the world itself. The joint members of a single culture hold in common many features of such a picture: they have a common understanding of subsistence problems, for instance, and overcome them by techniques different from those used by members of other cultures. All this was implicit in the discussion in chapter 1 on the nature of culture. The reconciliation in practice of all these pictures of society, possessed by its members, results in the social system. And to alleviate the mystery of the world beyond, the au-delà, the reach of the unknown, society forms a picture of the controlling forces, giving them superhuman forms to which man may appeal and which may intercede for him. These pictures are projections: the society projects man’s fears and aspirations onto the world, makes gods in his own image, and acts out in religious or civic ritual his hopes and fears.

In this way the abstract becomes concrete: feelings or thoughts dimly felt or sensed, are given form—the forms are symbols of the idea. Ernst Cassirer has well expressed this special feature of human experience and human behaviour (1944, 24–25):

‘No longer in a merely physical universe, man lives in a symbolic universe. Language, myth, art and religion are parts of this universe. They are the varied threads which weave the symbolic net, the tangled web of human experience. All human progress in thought and experience refines upon and strengthens this net. No longer can man confront reality immediately; he cannot see, as it were, face to face. Physical reality seems to recede in proportion as man’s symbolic activity advances. Instead of dealing with the things themselves man is, in a sense, constantly conversing with himself. He has so enveloped himself In linguistic forms, in artistic images, in mythical symbols or religious rights, that he cannot see or know anything except by the interposition of this artificial medium.’

In a sense, most of the activities of man can be considered in this way, as we saw in chapter 1, interposing a cultural buffer between himself and the world of nature. Some of them of course are simply logical and direct responses to his primary needs and their immediate derivatives—the subsistence activities, those of craft production, of securing goods over distances, even of ‘living together in cities’. These are elaborations of activities already seen in simpler form among other species—for instance in a beehive. In other concerns, however—and this is what interests us in this chapter—aspects of the world-picture are actually given tangible symbolic form: images of the gods are fashioned, regalia instituted for the ruler, sorrow and desire expressed in song and dance. It is to these patterns of activity, where man’s understanding, feelings and thoughts about his world are given formal and often concrete expression, that the name symbolic or projective systems is here given.

The whole field of religious activity of a culture forms a particular projective system: a temple or shrine and all the observances related to it respond to man’s view of the world. Their urgent reality, for the culture to which they belong, is no less than the reality, for instance, of the subsistence subsystem with its inflexible exigencies. Religion and ritual constitute a complex and expensive technology for dealing with the unknown, a major projective system.

Often, too, alongside the social system and indeed a part of it, are activities and objects specifically symbolising the social realities to which they relate. The king wears his crown, the pharaoh lies buried in his pyramid; and the coronations and royal burials form part of another projective system symbolising, and stabilising, the social order.

The whole world of the arts—painting and sculpture, acting and mime, music, dance—gives formal expression in the analogous way, to man’s feelings in face of the world: these too are projective systems.

Some of these activities are often classed as non-functional. Yet the religious activities of a culture, for instance, however meaningless they may seem to an outsider, have a real and vital role within it. To regard them as ‘non-functional’ is to make a subjective judgement, and to undervalue the role which non-material concepts have in many societies. To the society’s members they may have a more lively reality than, for example, an accounting system, which is to the same extent a projection of a world-picture as is a series of religious formulae. The notion, for example, of an annual obligation on a stock-farmer of so-many sheep, irrespective of the fluctuations of fortune, is a very abstract one, yet is highly functional on anybody’s definition. In the Minoan-Mycenaean palaces purely utilitarian accounts are found side-by-side with tablets, interpreted as recording offerings to various deities. No purpose is served by designating one obligation as non-functional, the other as functional.

These considerations are all relevant here since the symbolic systems have a real interaction with the other subsystems of society. Stonehenge, or the Treasury of Atreus, or the Pyramids are artefacts which undoubtedly impinged upon and meshed with the economic system, but they are intelligible only as projections of concepts about the world. The movements of the sun and moon mattered to the inhabitants of southern Britain in the later third millennium BC, just as the death of a ruler mattered at Mycenae or in Old Kingdom Egypt.

In the sections which follow, various aspects of the projective systems of Aegean prehistoric society are discussed, with particular reference to the evidence for their early development. They bring us close, once again, to the core-idea of what civilisation is.

In defining civilisation in chapter 1 as the multi-dimensional environment created by man, detailed reference was not made to man’s world-picture as conceived here, since this is an abstraction which for the archaeologist is difficult to handle. But civilisation may certainly be viewed in these terms—by reference to the progressive and fundamental changes which man’s view of the world, and the world-view shared by the participants in a culture, undergo. This is precisely why many historians of culture put particular emphasis on the symbolic system and especially upon the arts, as manifestations of civilisation. In chapter 1 we saw how some writers, such as Frankfort, think in terms of ‘style’ when defining civilisation. Such an approach has not been followed in the present work, but certainly a culture’s symbolic achievements—its monuments, its literature, and so on—give a deep insight into the multi-dimensional environment which its members came to create for themselves, and in which they lived.

The growth of Aegean civilisation cannot be understood without a consideration of the changes in the projective systems. Their development in the third millennium is considered in the succeeding sections.

Language must undoubtedly be man’s earliest descriptive system. By neolithic times in Greece the spoken language, inevitably, will have been a flexible instrument. Very possibly, languages ancestral to more recent Indo-European languages were already spoken in the Aegean, although this can only be conjecture. The language of the Mycenaean world and of the late occupation at Knossos, as reflected in the Linear B tablets, is now widely (although not universally) recognised as Mycenaean Greek. It is possible that in early bronze age times, the language of mainland Greece and perhaps of other Aegean areas may have been the direct ancestor of Greek. But whether this is so or not, verbal expression may be assumed to have been so effective, already long before that time, that changes in the language during the bronze age can have had only a marginal effect upon its practical effectiveness as a descriptive system.

Certain new concepts, however, do seem to have emerged. And while, from the modern standpoint, the invention of written language seems the major civilising achievement, during the bronze age it was probably in the first instance simply a further aid in overcoming the problems of mensuration and reckoning.

Already in chapter 18, the evidence of seals and especially sealings as suggesting the development during the early bronze age of a redistributive system, has been indicated. Underlying the existence of an orderly exchange organisation there must be several very fundamental concepts. The first and most crucial of these is the potential equivalence of goods and services.

Of course in neolithic times, goods were undoubtedly frequently exchanged, sometimes in fulfilment of obligations, and on other occasions by barter. A man wishing to obtain obsidian from his seafaring neighbour will have received it, perhaps, in exchange for grain. No doubt approximate units of equivalence may have been established, just as the oxhide ingots of the late bronze age (fig. 20.6) are often supposed (although perhaps without good evidence) to have been worth one ox.

The systematisation of such concepts made possible the centralised storage of goods, in the House of the Tiles, for example, or later in the palace stores (see chapter 15). It meant too that one party in an exchange transaction did not necessarily receive his repayment at once, whatever its ultimate form, when delivering his own produce. Undoubtedly his contribution will have been of definite recognised value, not solely in its own terms (e.g. if wheat in terms of bushels of wheat) but in terms of other commodities, or services which he could expect in return. The crucial importance of such an exchange system, such an equivalence however organised, is discussed in the final chapter.

Already a redistribution system of the kind seen fully developed in Mycenaean society hints at the need for written records. There was apparently no organised market, with a direct exchange rate for various commodities: individuals had instead long-standing obligations for payment in kind, and a record of such payment was required. Until the system became too complex the records could be kept orally, by public agreement. But already a prior necessity existed for units of quantity, and for a numerical system to compound them. A prerequisite for any redistributive system handling real commodities is a means for determining their quantity Units of size, weight and capacity are essential

By the late bronze age lead weights, specially made in disc form, are seen at Phylakopi in Melos (pl. 18, 3; Renfrew 1967a, 4, pl. 2a; Atkinson et al. 1904, 92). A whole graduated series of them has been found at Aghia Irini on Kea (Caskey 1969, 439, fig. 9) where they were multiples and subdivisions of a unit of about 65 gm. Similar weights have been found at several late bronze age sites in Greece and Crete and in the Cape Gelidoniya wreck (Evans 1921–35, IV, 654; Karo 1933a, 247; Bass 1967).

Bronze scales were found in a grave at Mavrospelio near Knossos, together with weights (Forsdyke 1927, 253, fig. 6), and similar scales have been found in Mycenaean contexts at Mycenae, Vapheio and Thebes, and ‘symbolic’ or toy scales of gold in Shaft Grave III at Mycenae (Wace 1932, pl. XXIX, 20; Karo 1933a, 247 and pl. XXXIV). Earlier finds of scales are not known, but it seems likely that weight will have been used as a criterion of quantity as soon as materials were available of sufficient worth to make precision desirable. This supposition is confirmed by a very interesting find from early bronze age Troy.

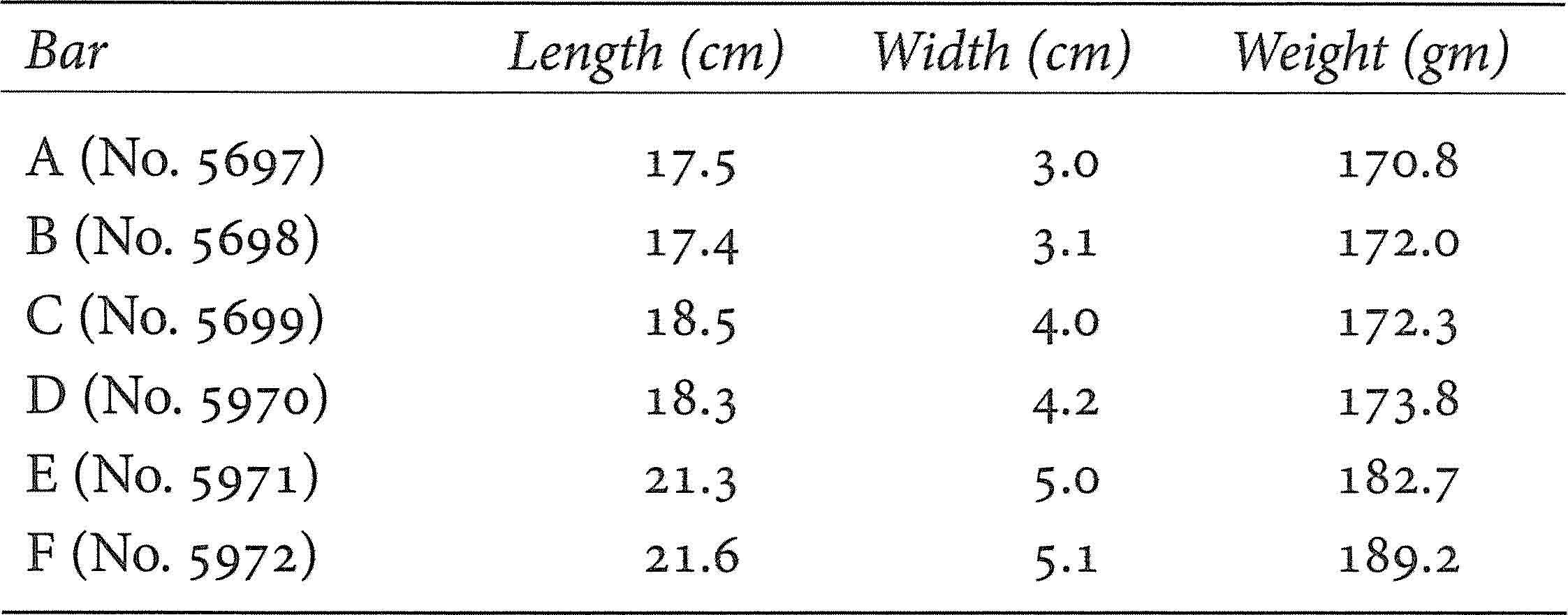

In the ‘Great Treasure’ of Troy II, amongst the metal plate and the weapons, six ‘bullion bars’ of silver were found (fig. 19.1). Their dimensions are given In Table 19.1 (Schmidt 1902, 237, although there is a misprint here in the weight for no. 5970, cf. Schliemann 1880, 470, nos. 787–92).

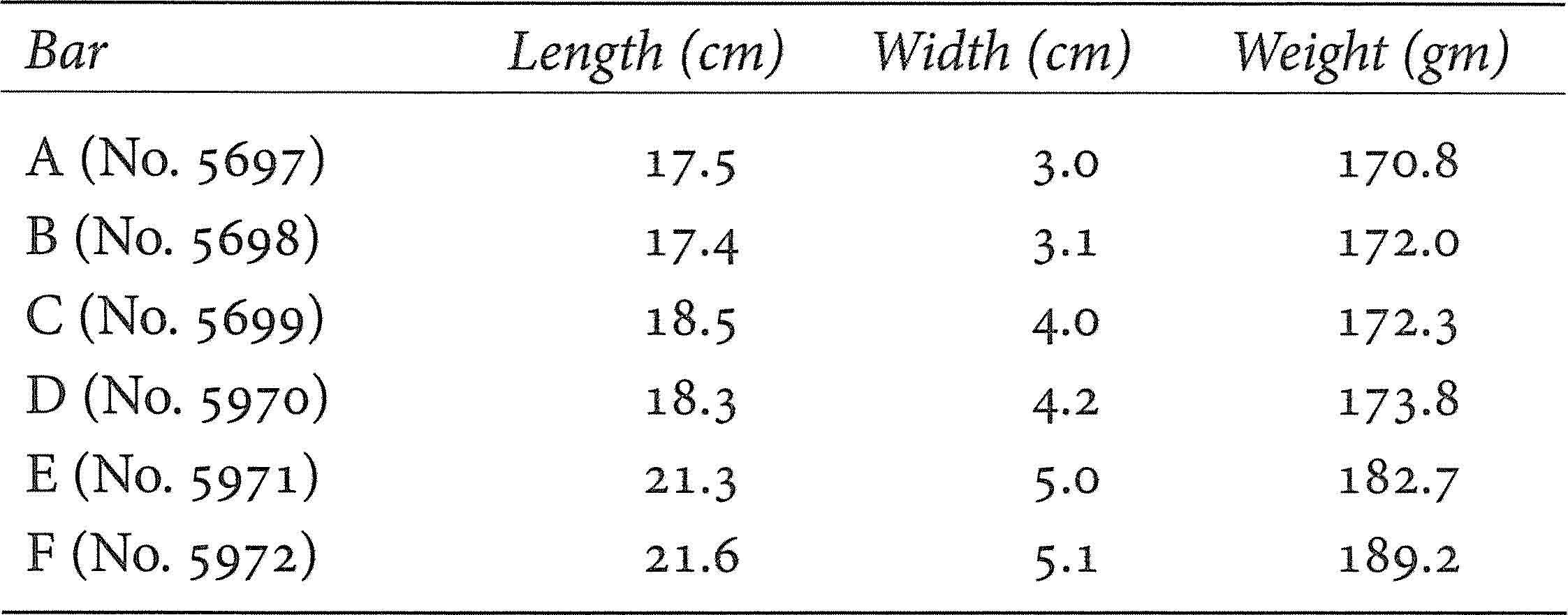

TABLE 19.1 Dimensions of silver bars found in Treasure A of Troy II.

These bars are obviously in pairs: this is clear from the length and width, without considering the weight. Comparing now the weights within pairs, we find they are exceedingly close, nos. A and B differing by only 1.2 gm, C and D by 1.5 gm, and E and F by 6.5 gm—respectively 0.7 per cent, 0.9 per cent and 3.6 per cent of the weight of the bars. These figures are so close particularly when the corrosion of the bars and the reported accretion of oxidation products, especially on Bar F, be considered. Each bar was clearly intended to be the same weight as its partner.

The first pair (A and B), taken with the second pair, yield a mean weight of 172.2 gm, with a mean variation of 0.8 gm, or 0.5 per cent. Again the two pairs were obviously intended to be the same weight, although the shape is slightly different. Such precision can only have been achieved with considerable competence in weighing.

The third pair differs so much from the others that a different weight was probably intended—the six bars, if lumped together, have a mean weight of 176.8 gm, with a much larger variation of 6.0 gm or 3.4 per cent. While it seems too ambitious to recognise these as ‘the third part of the Babylonian silver mina of 8656 gm’ (Sayce in Schliemann 1880, 471) we may at least draw the important conclusion that the early bronze age smiths of Troy were weighing bullion to an accuracy of a gram or two.

FIG. 19.1 Evidence for mensuration: silver ingots from the Great Treasure of Troy II (after Schliemann). Max. length 22 cm.

Though it is not yet possible to document for the early bronze age the existence, even locally, of weight standards such as existed in the late bronze age, it seems likely that such standards developed locally as weighing became a routine operation. Certainly by the late bronze age a complex system was in operation. The important find at Knossos of a large stone weight of 29 kilos, decorated with an octopus carving, is supplemented by the copper ingots from Aghia Triadha, which are likewise of 29 kilos. This is a unit which Ventris and Chadwick have assumed to be the ‘talent’, the largest weight unit of the Linear B tablets.

The existence of units of capacity in late bronze age times is likewise documented by the tablets (Ventris and Chadwick 1956, 55; Palmer 1963, 14). Units of measure for subsistence and other commodities in the middle bronze age are implied by the hieroglyphic inscriptions (Evans 1921–35, 1, 282; Ventris and Chadwick 1956, 31). But the archaeological record does not so far document these units, and there is therefore no hope at the present of carrying them back into the early bronze age.

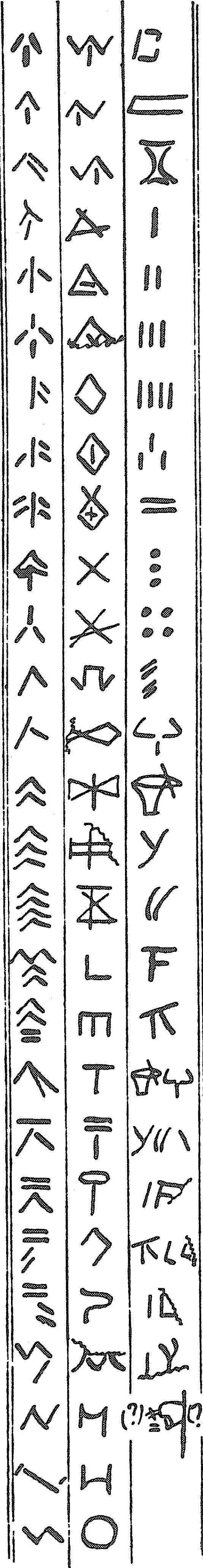

Mensuration implies an efficient counting system, and this again is amply documented by the tablets. A decimal notation was adopted for the hieroglyphic tablets of the Minoan late bronze age, and continued with minor changes in notation into the Linear A and Linear B tablets.

Fractional quantities were handled in the middle bronze age by means of straightforward vulgar fractions, sub-divisions of the unit in question, and the same method was used in the Minoan Linear A script. But in Linear B a new more sophisticated system was adopted, analogous to our own complicated one for weight: 1 ton, 3 cwt, 2 qr, 15 lb, etc. Instead of employing a fractional notation, a whole hierarchy of smaller units was employed: each unit is indeed a specified fraction of the preceding, but the writing of fractions is avoided. This dearly implies a whole series of named units in a fixed relation, one to another. In the early bronze age simple vulgar fractions are more likely to have been in use. The Minoan numerical system was used for addition and subtraction and could have been used for multiplication, division, and even the extraction of square roots, although such use may be unlikely (Anderson 1962).

These developed concepts of number were not simply applied to movable objects. Graham (1960; 1962, 226) has discussed how Minoan architects laid out their palaces using a standard measure of length, the Minoan foot, of 30.3 cm. The major dimensions of the palaces were round numbers of this basic unit: the central courts of Phaistos and Mallia measured 170 by 80 Minoan feet, while that at Knossos seems to be of the same order. There can be no doubt that the Minoan palaces were carefully planned in advance: there is little haphazard or informal in their disposition. Since the palace at Mallia was originally laid out, probably in much its present form, in the Middle Minoan I period, this metric and architectural competence was already available early in the second millennium BC.

Indeed Caskey suggests that the dimensions of the House of the Tiles at Lerna may indicate the use there of a foot of 30 cm, various walls, doorways and staircases apparently having been laid out using this foot (1955a, 40). The length and width of the House of the Tiles may be interpreted as 80 and 40 feet respectively, and the earlier structure below the House of the Tiles has a comparable width.

Another possible case of careful metric planning during the early bronze age, involving ratios, without a fixed unit of length, is offered by the Early Cycladic folded-arm figurine. Preziosi (1966b, 20) has suggested that many of these adhere to strict canons of proportion, laid out with the aid of compass and ruler. Critical assessment of this very interesting suggestion must await the full publication of her study: her arguments do, however, seem very plausible, and may account for some of the peculiarities and variations in the proportions of these remarkable objects.

Great competence in the measurement of weight and of length is thus already attested in the early bronze age, possibly with the use of standard units such as are clearly seen in late bronze age times.

Curiously, however, there is no evidence in the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation for astronomical observation or computation. What are interpreted as month names appear on the tablets (Ventris and Chadwick 1956, 304), with lists of ‘ritual offerings’, presumably gifts appropriate to a particular time of year. But there are no texts like those of Babylon or Egypt relating to astronomy. Nor are there monuments, such as those of Central America or prehistoric Britain, of calendrical significance. The central courts of the three principal palaces of Crete were indeed oriented along the same axis, approximately north-south. But there is no need to relate this to careful astronomical observations. Two thousand years after Stonehenge, time was still reckoned in Greece in the informal manner employed by Hesiod:

‘The cry of the migrating cranes shows the time of ploughing and sowing.’

‘Vines should be pruned before the appearance of the swallow.’

‘When the snail climbs up the plant there should be no more digging in the vineyard.’

Undoubtedly the Minoans and Mycenaeans will have observed the movement of the stars. Yet it is somehow typical of these civilisations that the passage of the months should be noted, not by reference to the movements of the celestial bodies, but of the birds and even the invertebrates of the terrestrial world.

The two basic elements of any system for recording are distinguishing marks, and a numerical notation. Even in the late bronze age these form the essential of the records, where almost every line ends with an ideogram (designating the commodity) and the number (indicating quantity). The syllabic text of the tablet merely amplifies the description of the goods, and specifies their source or destination.

As we saw in chapter 18, seals and sealings of the early bronze age already fulfilled some of these functions, indicating ownership (or source), and possibly also the nature of the commodity.

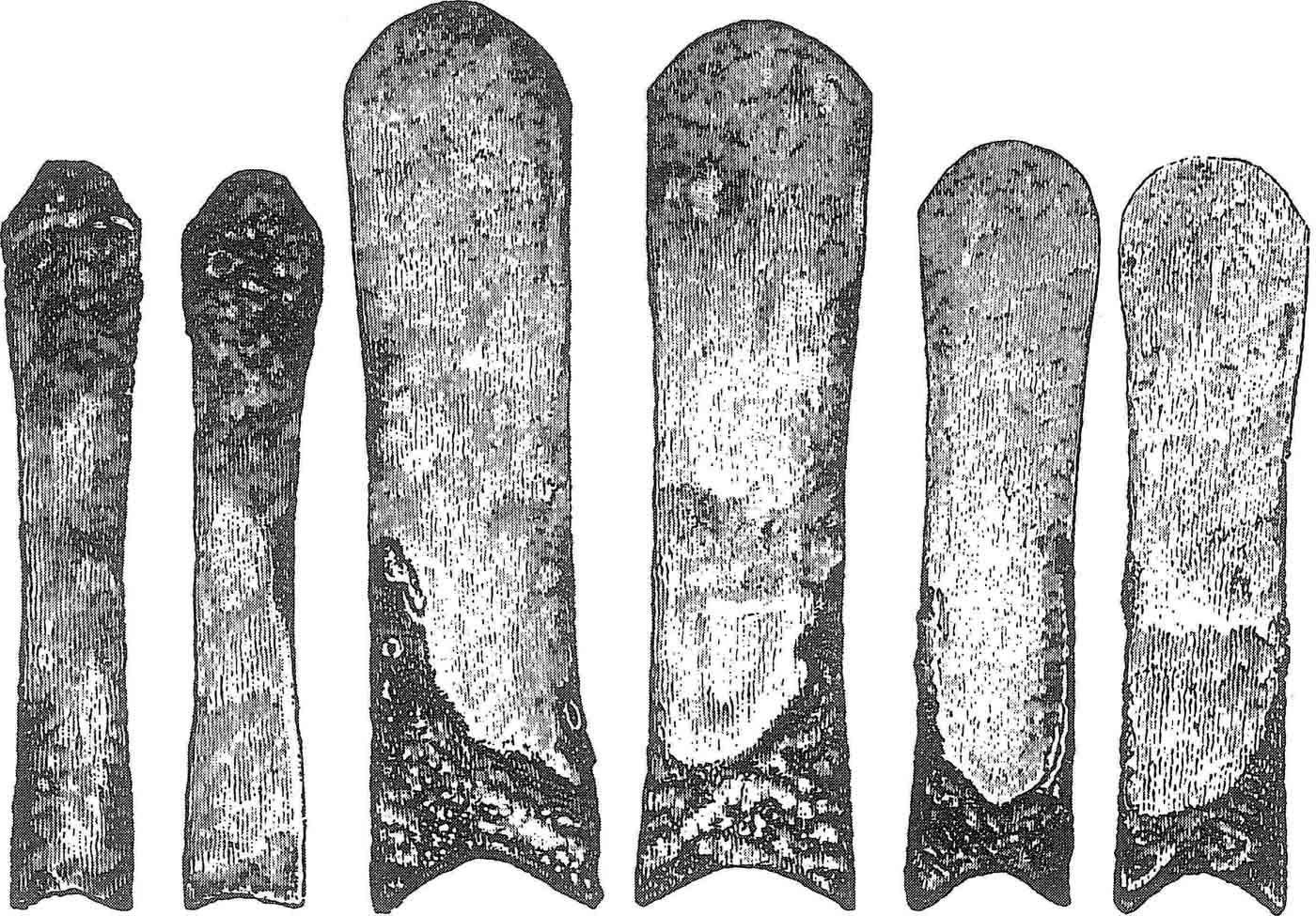

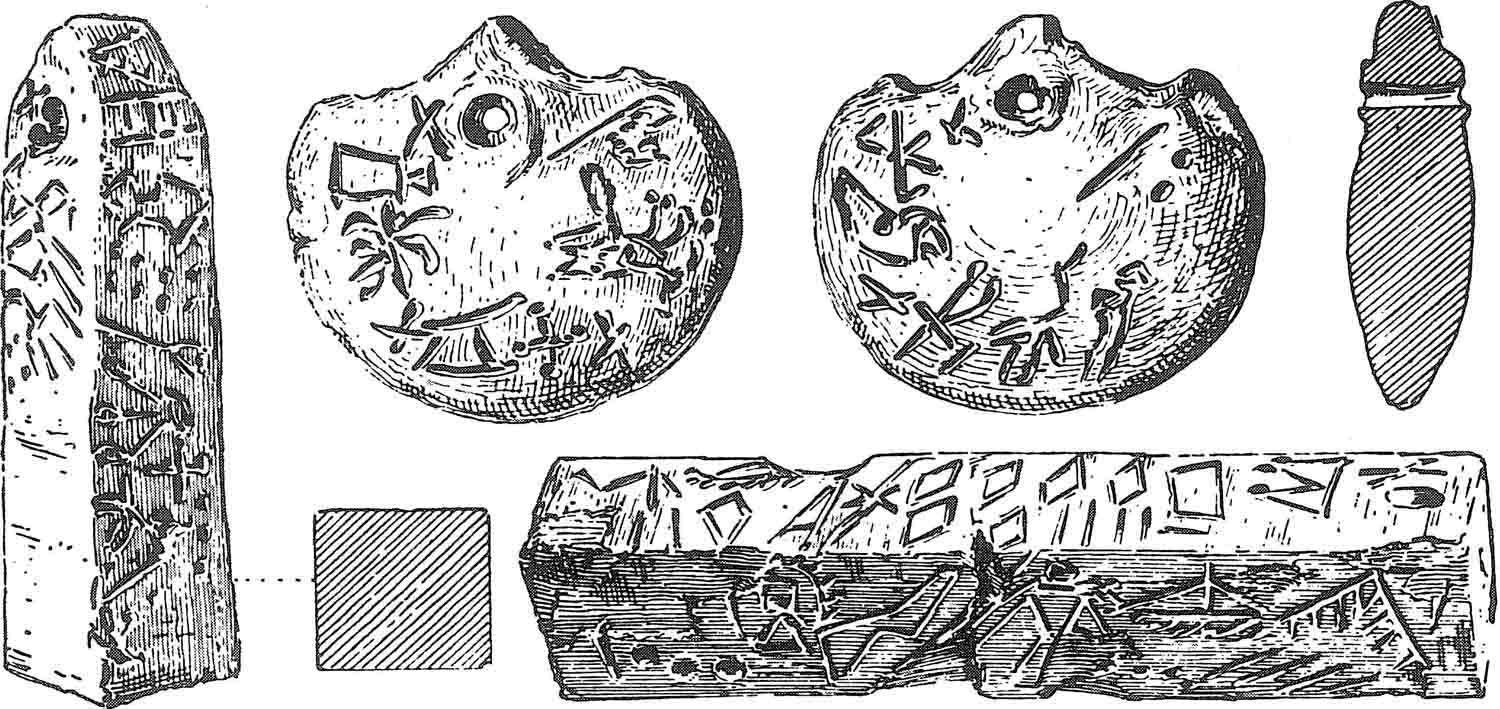

During the early bronze age there was also a series of pot marks, especially at Phylakopi (fig. 19.2). These marks incised on the body or more generally the base of the pot before firing obviously embody a numerical notation.

It is possible, indeed, in the Aegean to see an evolution in the expression of meaning by means of incisions upon clay. In the late neolithic at Sitagroi in Macedonia, clay roll-cylinders are seen with incised decoration, which, like those of Poliochni (Yellow) and Kapros in Amorgos, will have been used to stamp moist clay. At the same time in the Balkans, around 4000 BC in radiocarbon years, signs were incised on pots and even on clay tablets (Todorović and Cermanović 1961, 42; Schmidt 1903, figs. 38–39; Vlassa 1963, 485). They bear a superficial resemblance to the pot marks of Phylakopi I some two millennia later. In phase III at Sitagroi many spindle whorls are found with incised motifs, which are simply decorative in intent. These are rare in phases IV and V at Sitagroi, but analogous incisions become very common at Troy during the early bronze age (fig. 17.3). The percentage of the whorls at Troy which are decorated in this manner is as follows: Troy I: 9 per cent; Troy II: 22 per cent; Troy III: 39 per cent; Troy IV: 68 per cent; Troy V: 62 per cent; Troy VI: ‘marked reduction’ (Blegen et al. 1950, 50 and 217; 1951, 15, 116 and 232). Schliemann considered these signs on Trojan spindle whorls, and also cylinder seals, to represent writing, comparing them indeed with those of south-east Europe. Sayce even attempted their decipherment (Schliemann 1880, 691). Since these signs in the Balkans and Troy were not succeeded by the development of a well-defined hieroglyphic script, to regard them as writing hardly seems warranted. But we should none the less recognise that the Balkan signs are not markedly different in kind from pot marks seen at Phylakopi and elsewhere, and that the evolution of signs on the whorls has points of comparison with the development of the Early Minoan seals.

Evans (in Atkinson et al. 1904, 181) made a systematic study of the ‘pottery marks’ found at Phylakopi largely in levels of the First City, and recognised among them four classes:

1. Geometrical marks either traditional or of arbitrary origin;

2. Pictographic signs;

3. Signs identical with those of the Knossian Linear script;

4. Numerals.

Unfortunately, it is not now possible to specify the stratigraphic context of each group, for Hogarth (1898, 12) wrote of Aegean signs on pottery evidently of the Second and Third Cities also. But it is clear that signs were first incised on the pottery in the early bronze age, and continued to the middle and late bronze age, when signs of the Minoan Linear A and B scripts are seen. A sherd of Middle Helladic Grey Minyan ware from Naxos is also incised with a Linear A sign (pl. 26, 2). Pottery marks or signs of this kind are common in mainland Greece during the middle bronze age, although they are not apparently found during the Tiryns culture.

FIG. 19.2 The beginnings of writing: incised signs on pottery from Phylakopi in Melos (after Hogarth).

The Hieroglyph Deposit, which at Knossos first documents a coherent written notation, is dated towards the end of the Middle Minoan period (cf. Kenna 1960, 37 f.). But the important and earlier series of sealings of Middle Minoan Ib/IIa date from Phaistos implies a meaningful notation, although hieroglyphic inscriptions are not included (Levi 1958; Fiandra 1968). Hieroglyphic signs are seen on seals of the ‘Early Minoan III’ period (Hutchinson 1962, 64), and Branigan (1969a, 17–19) has stressed the affinities between signs on the Phaistos sealings (and on Early Minoan sealstones) and those of the early hieroglyphic script.

It would thus be possible to claim that ‘writing’ began its development in the Aegean during the early bronze age. Certainly the use of sealstones (which, as emblems of ownership, are already signs of a special kind) involves the use of schematic signs. Signs are seen on pots too, and from the Middle Minoan I period on building-stones. Doubtless they occurred on other less permanent classes of objects. However it seems safest to view such signs and seals as simply a stage where linear decoration and the use of symbols merge inextricably, as at Troy, and as earlier in the Balkans. Out of this wealth of linear decoration and of symbolism, hieroglyphic writing, embodying significant sequences of such signs, emerged during the First Palace period.

FIG. 19.3 Hieroglyphic inscriptions on clay tablets of Middle Minoan date from Knossos (after Evans). Scale almost 1:1.

Kenna has written (1962, 1): ‘In all Asian civilisations where seals have been used, there has also been a tradition of writing. It would seem that the very impress of the seal upon the clay which was to secure a door, chest or jar and so prevent unauthorised entry, inclined Asian people to use and make other special and recognisable signs to identify, record and then to communicate with one another; to be understood by sign as well as by sound.’ This effectively expresses the frequent connection between the two activities. Both were indispensable operations of the developed palace redistribution economy.

The next stage in the development of writing, the use of signs to represent sounds rather than ideas, may have come about under the influence of the Near Eastern syllabaries, then in being. But it is not inconceivable that the transformation from ideogram to syllabic symbol was a local one. Hutchinson (1962, 65) has suggested that such developments can already be discerned in the later hieroglyphic script in Crete: ‘The A hieroglyphs were usually executed as silhouettes, though sometimes internal details were carefully recorded: but those of Script B or “the developed hieroglyphic script”, as it is often called, were executed in a more summary fashion, outlines already suggesting that a conventional script would develop out of the old hieroglyphs.’ The Minoan Linear A script may have developed from the advanced hieroglyphic script. Significantly perhaps the change to a more elaborate (and probably Near Eastern) fractional notation did not occur until later.

In any case, Minoan writing, as the evidence has come down to us, was not much used other than for accounting purposes. As Dow (19554, 127) rightly concluded: ‘The Cretans expressed themselves more and better in other ways than In writing’ Just a few objects are preserved with inscriptions, in some cases dedications perhaps, in the Minoan Linear A script (Pugliese-Carratelli 1957; 1963). But we have neither the long religious texts of the Egyptians nor the monumental inscriptions of the Mesopotamian kings. Writing in the Aegean was a practical instrument, permitting the use of pragmatic concepts of number, of weight and measure, and the compilation of dues and of inventories. Other kinds of text may yet be found, but so far the only abstract concepts and symbols which they embody are these utilitarian and organisational ones. The record shows that some of these concepts were already developing in the early bronze age.

Counting and measuring are activities employed to systematise and codify the physical world, which happily do leave some trace in the archaeological record. The primacy of language as a symbolic system has already been indicated, but unfortunately there is little the prehistorian can say in this direction. The vocabulary would certainly, if known, yield an important Insight into the Interests and preoccupations of the community. Some modem food-gathering communities, for example, have exceedingly full and elaborate vocabularies for plant species, and several Arabian tribes have rich and complex vocabularies relating to camels. The ‘pre-Greek’ words preserved In classical Greek must presumably have been in use in Greece at least prior to the late bronze age. Those designating plants are very numerous, and exceed in precision the vocabulary of modern demotic Greek, where so many plants are dismissed as chorta. Of particular note are bussos and karpessos, both words for flax, a plant perhaps not used before the early bronze age. Birds were also classified with more precision than in recent times.

A keen eye for nature is reflected also In the art of the late bronze age, where the botanical detail was sometimes very closely observed. Möbius (1933) has discussed Minoan plant representation: the white lily, the beach narcissus, the saffron flower, Iris and myrtle are commonly seen in faithful detail. Olive leaves, fig trees and date palms also occur as well as the papyrus plant. Some of these plants are represented already in the middle bronze age, and the Early Minoan gold jewellery at Mochlos included sprays of leaves, and a golden flower (fig. 6.8).

Another favourite source of subjects was the sea, and in the Late Minoan Ib period the octopus and nautilus especially, among marine subjects, are frequently seen. Birds, the third subject of special interest to the Minoan nature painters, have been the subject of special study by Miss Sylvia Benton.

Karo (1933a, 293) has analysed the animal species represented among the finds of Shaft Grave Circle A at Mycenae. The result is interesting, for in the Mycenaean world the interest seems to have been rather in animals than in plant or marine life. The order of frequency of species was as follows:

19 occurrences: lion; 12: bird; 10: horse; 6: stag and griffin; 5: octopus; 4: leopard and ox; 3: dog; 2: butterfly, dolphin, antelope; 1: panther, wild goat, fish, mussel, nautilus, sphinx, sea monster.

The emphasis here on animals of the chase contrasts with that in Crete, where bulls, Cretan wild goats, monkeys and marine subjects are most common among the animals.

Of course the choice of subject is very much an artistic convention. The scarcity of animal representations on the pottery of the neolithic and early bronze age is a reflection above all of the art style of the period. In fact, carvings and stone beads of birds are not infrequent in the Cycladic early bronze age, and in Crete we have ivory seals in the form of birds, monkeys and lions.

Emily Vermeule (1964a, 317) has listed the plant and animal species recognised in Mycenaean art, as well as in the Linear tablets. Trees seem distinctly under-represented when comparison is made with the range of species in the vocabulary used by Homer. Edible plants and domestic animals, although naturally more common on the tablets, do not emerge as a popular subject for Illustration. The overwhelming emphasis in the art is on wild plants, wild animals, birds and marine species.

Human beings are seen In frescoes and decoration (although rarely on the pottery) during late bronze age times. In earlier periods, however, the human representations are rarely just decorative in intention: they are figurines or statuettes made with a specific, often religious, purpose. Monsters and Imaginary beasts are not an important feature of Minoan art, although the griffin and sphinx occur occasionally in late bronze age times (Nilsson 1950, 368 f.). Curiously, however, imaginary beasts are seen on Middle Cycladic vases (Zervos 1957, figs. 268 and 271): probably they are simply a decorative frivolity. In general, prehistoric art in the Aegean was not inspired by the fecund imagination of the Mayas or Aztecs, nor by portentous scenes of human affairs.

From this discussion, we can begin to glimpse the picture which the Minoans and Mycenaeans had of the physical world, and how they felt able to describe It. It seems in some ways similar to our own, with a sound grasp of weight, measure and reckoning, and a vivid appreciation of nature. Nearly all the descriptive devices of the late bronze age already had their origin in the third millennium.

Perhaps because men wish their society to conform to the image or picture they have of it, the appearance is as important in human affairs as the reality ‘Justice must not only be done: it must be seen to be done’ is a philosophy which permeates most cultures: a bank should look prosperous and secure—like a bank in fact; the home of a ruler must look like a palace; if there is to be a funeral, let it be a good funeral

This outlook need not necessarily imply the conspicuous consumption or display of wealth, or competition: it is more than just ‘keeping up with the Jones’s’. The desire is simply that the reality should conform to society’s picture of it: it should symbolise itself. This desire is fulfilled by the symbolic forms with which the reality of leadership are clothed: the royal throne in the royal palace, the royal tomb, the princely processions.

The throne at Knossos (fig. 18.5) and the regalia of Mallia (fig. 18.6)—the great long-sword and the ceremonial battle-axe—have already been discussed. They are the symbols which society needed to emphasise its structure. Monumental tombs, such as the Royal Tomb at Isopata near Knossos, or the Mycenaean tholos tombs, also emphasise the pre-eminence both of the deceased ruler and of his successor.

The might and ferocity of the warrior was emphasised by the magnificence of the weapons buried with him—here the inlaid daggers of the Mycenaean Shaft Graves, and the choice of weapons in the Warrior Graves at Knossos emphasise the point. The hard fighter was also a hard drinker, and gold cups often accompanied him to the grave; at Zapher Papoura, a complete outfit for drinking was buried (fig. 21.2).

The culture of neolithic Greece gave little scope for such symbolism, although doubtless such evidence as may have existed has disappeared. There were few specialist craftsmen, and the skilled man would not automatically have been recognised by the tools of his trade, like the occupant of the carpenter’s grave at Zapher Papoura (fig. 17.1). While there may have been village leaders, there were no regional princes to be commemorated by monumental built tombs. There were no central administrative buildings to be embellished with frescoes and dressed stone. There were no stone-built fortifications whose strength might be symbolised by guardian lions, as in the Lion Gate at Mycenae.

During the early bronze age many of these symbolic forms can be seen to emerge. The weapons of display of Treasure L of Troy II (fig. 18.4) perhaps symbolise the supreme status of the ruler at Troy, just as did the leopard axe at Mallia. The beautiful gold and silver drinking vessels of Treasure A not only document for us the wealth of the ruler of Troy II. Undoubtedly they symbolised for his citizens the prosperity and magnificence of their chief.

Again, the military prowess of the chiefs of early bronze age Levkas is not merely documented by a bronze dagger or two: it is symbolised by the decorated golden sheath which covered that dagger’s hilt (fig. 18.3, 1). In the same way, in the silver daggers of Early Minoan Koumasa we may see the prototypes of the superb weapons of display of the late bronze age. The pre-eminence of the rulers of the Plain of Nidri in Levkas and of their families was marked also by the erection of large circular cairns, up to 9 m in diameter, above their remains—just as a grave in a special precinct, and marked with a stele, commemorated the Early Mycenaean prince, and a magnificent built tholos his later bronze age successor.

By contrast, however, there is yet no evidence that the central buildings of the early bronze age communities or strongholds were embellished or given symbolic indication of their importance. The House of the Tiles at Lerna and the Tiryns Rundbau are impressive only for their size (although the predecessor of the House of the Tiles, building BG, had a splendidly ornamented clay hearth (pl. 20, 3). The central buildings at Troy II are most notable for the movable objects found in them, not for decorative or architectural distinction. And the complex structures at Vasiliki or Myrtos (Phournou Koriphi) in Crete are not visually impressive. The authority and status of the early bronze age chiefs was symbolised rather in his possessions—arms and plate—and in his burial Not until the emergence of the principality in middle bronze age Crete is the seat of government and the house of the ruler laid out, constructed and decorated in a manner eloquently expressing these functions.

All human cultures create and sustain a system of beliefs which make intelligible to us those forces and events which seem totally outside of human power. Sun, moon and seasons, rain, drought and fertility, birth, death and misery are all themselves gods or else the gifts and attributes of gods. In order to bear the insistent reality of these forces, man tames them at least a little by naming them. By personification they become intelligible in human terms: the thunder of the storm is a manifestation of Zeus’s anger, the earthquake Is sent by Poseidon the Earth Shaker. And the mysteries within human life become in some way comprehensible or at least bearable by the same process of projection. Sickness and death may be less frighteningly unique events if related to the experience of others, as another direct hit for the death-dealing darts of Apollo.

Of the actual beliefs of the prehistoric Aegean, the myths through which the present world and its creation were made intelligible, we can know little. We can, of course, look backwards to that time, through the eyes of the classical world, encouraged by the recognition in the Linear B tablets of divine personages bearing names like those of the Greek gods and heroes. But to recognise the Greek deity in his Mycenaean predecessor merely impedes our understanding of the evolution of the concept.

In all human communities a knowledge of this irrational world of superhuman powers Is accompanied by specialised techniques for influencing these powers. Highly specialised procedures will secure the attention, sometimes even the material presence, of the spirit or the god, and divine intervention or intercession may be obtained.

Sometimes the cosmology of the society is a more complex one, and the interior causal mechanism of events much more complicated than the informal interplay of divine wills, with all its very human idiosyncrasy, with which Homer depicted the Greek pantheon. In such a case the world order is not to be influenced merely by the simple agency of a decent and proper respect, the avoidance of impiety, and an occasional libation. The Chinese, and the early Mexicans, in their different ways had a more complex notion of the world order, and more exacting techniques for keeping the world in its right course and for inclining Nature to benevolence towards man. In China, the year’s prosperity depended on the correct performance of sacred contests at seasonal feasts: without their proper accomplishment the crops would not ripen. The Aztecs sacrificed hundreds of human victims to sustain the sun in its arduous course.

While we can know little of the precise dogma of prehistoric religion, the activities which were used to propitiate the forces of the unknown leave very clear traces. Many prehistoric societies evidently devised an elaborate and expensive technology to safeguard the position of society in the world, and another related technology to facilitate the auspicious departure of the deceased. And even after his journey ‘to the other side’, observances and precautions perhaps helped either to ensure his welfare there (as, for example, the masses for the soul of the departed in the medieval chantry chapel) or to prevent his maleficent return.

The religion of the late bronze age Minoans has been documented by a series of finds from shrines within the palaces, and at holy places within caves and on the summit of mountain peaks in Crete. The representations on seal stones and rings and elsewhere add to this picture, and make possible the identification of a number of recurring religious symbols and deities.

Curiously, however, the cult figures from Crete are all small in size, and very few representations of gods or goddesses have been found amongst the many votive figurines. This is in contrast to the recent finds at Aghia Irini in Kea of a small ‘temple’ with large, more than half life-size, terracotta figurines. We cannot assume that the religions of the Minoan and Mycenaean civilisations were very closely similar. Certainly the wealth of reference in the art of Crete to religious symbols—horns of consecration, double axes, etc.—is less notable in the Mycenaean world.

In neither civilisation—and certainly this is true also to the Cyclades—did the religious beliefs and observances find monumental expression. In contrast to the religions of some of the great civilisations, those of Crete and Mycenae seem very domestic in character. The palace shrines seem insignificant little rooms, tucked away like the Shrine of the Double Axes at Knossos. The cult figures recently discovered at Mycenae had no magnificent architectural setting, and even at Aghia Irini in Kea the ‘temple’ is impressive only for its contents.

The almost subsidiary position of these domestic shrines is brought out by the impressive proportions of the Mycenaean megaron hall, with its hearth, and by the ample dimensions of the great courts of the Minoan palaces. The central court may of course have been the scene of religious ritual, but the most exciting and dramatic events likely to have occurred there were the bull sports. As Nilsson (1950, 374) observes, ‘It is often assumed that Minoan bull-fighting was a sacral performance, but there is nothing in the Minoan monuments to prove that it was more than a very popular secular sport.’ The only locations devoted entirely to religious observance seem to have been the ‘peak sanctuaries’, and the numerous sacred caves. Indeed, nothing in Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation conveys the same intensity of religious expressions as the shrines of neolithic Çatal Hüyük.

The deities of the Minoan religion—notably the snake goddess and the Mistress of Animals—have been identified by Nilsson in his admirable analysis. He follows Sir Arthur Evans in recognising the veneration of sacred trees or pillars, and the symbolic significance of the horns of consecration and the double axe. Birds are seen to indicate the epiphany of the deity. Some of these beliefs and symbols seem to have had an origin in Early Minoan times.

Unfortunately no shrines of Early Minoan date have been recognised—unless the incomplete circular edifice at Myrtos. So the only way of establishing the religious significance of early bronze age objects is by comparison with those of the late bronze age, or by their funerary context, or, less reliably, by the absence of other plausible explanations for their use.

For this reason the evidence for early bronze age religion in the Aegean is limited. And yet despite this there are indications of possible origins for many of the symbols and conventions of later periods. Indeed it was during the early bronze age that most of the forms of the late bronze age—the horns of consecration, the double axe—made their appearance.

The religious significance of the bird, so well argued by Nilsson, is foreshadowed in a splendid dish of the Cycladic early bronze age, probably from Keros (Doumas 1969, 172). It contains a row of sixteen birds, all cut from a single block of marble (pl. 24, 1). The existence of other such dishes is suggested by further finds. This bowl has been appositely compared to a pottery bowl from Palaikastro with a bird modelled at the interior. The various finds of bird beads and bird pendants of stone (Tsountas 1898, pl. VIII, 16, 17 and 23; Seager 1912, fig. 20, IV, 7) may of course be without religious significance, yet the very large size of this dish (41 cm in diameter) and the severity of the composition imply a high seriousness of purpose in its manufacture.

The double axe, the most frequent of the Minoan religious symbols, is seen in miniature at Mochlos. The Early Minoan Tomb II yielded a copper example and two in lead (Seager 1912, 36 and fig. 12). The same cemetery also yielded a terracotta object (ibid., fig. 48.31; see also Branigan 1969b, 32), identifiable as ‘horns of consecration.’ That this object may have served a useful function, such as that of pot support (Diamant and Rutter 1969, 147), does not diminish its significance as a prototype for the later cult symbol.

FIG. 19.4 Schematic marble figurines of the Aegean early bronze age. IA to IE, of the Grotta-Pelos culture; VI, Apeiranthos type of the Keros-Syros culture; VII, Phylakopi I type of the Phyiakopi I culture; Be, Beycesultan type; Ku, Kusura type; Tr, Troy type; A.O, Aghios Onouphrios type. Scale in cm.

Very evident symbolism appears also in the Cyclades, upon objects of a possibly ritual function. It is documented in several instances and differs markedly from that of Crete. The ‘frying pans’ from Cycladic graves have long been a subject for dispute, and their use is entirely uncertain. Their typology is discussed in Appendix 2, and the distribution is seen in fig. 11.7. They may conceivably have served as mirrors (when filled with water), or simply as dishes, perhaps to make libations. Possible counterparts in metal are seen in the Troad and at Alaca Hüyük (Bittel 1959; Mellink 1956). In any case, they undoubtedly embody identifiable symbols in their decoration. Both the Kampos type (pl. 4, 1; Zervos 1957, figs. 224–27) and the mainland type (Mylonas 1959, fig, 148) typically have a circular symmetry in the decoration. A central rayed disc is enclosed by one or two concentric circles, themselves composed of running spirals or linked concentric circles.

The Syros type sometimes has this star (Zervos 1957, fig. 210) greatly enlarged, although without the surrounding concentric circles (ibid., fig. 211; fig. 205 has the rays of the star near the perimeter, enclosing the field of spirals). More often, however, the whole central field of the Syros type is occupied by a lattice of concentric circles or spirals linked by lines to five or six neighbours (pl. 7, 1).

All the Syros pans depart from the circular shape, being elongated towards the handle. And nearly all of them, whether with disc, or spirals, or a combination of both, have an incised indication of the female pubic triangle in the exergue formed by this elongation. This symbol occurs so often, and compares so closely with the pudenda of the Cycladic marble figurines, that no other identification seems possible.

The field of spirals represents the sea, as the ships incised in it graphically indicate (pl. 29, 1), and the design is indeed very evocative of the glittering, multi-faceted surface of ‘La mer, la mer toujours recommencée’. This identification of the circles, formed of linked spirals, seen on the Kampos-type pans is supported by the fishes swimming amongst them, seen in the pyxis lid from the Louros grave (Zervos 1957, fig. 228).

The central rayed-disc may reasonably be identified as the sun. On the Louros pan it could hardly be a star. The same symbol occurs on the diadem from Syros, flanked by animals behind which it appears again (fig. 18.1). Possibly it is actually drawn by them across the sky, like the bronze age sun-cart from Trundholm in Denmark (Klindt-Jensen 1957, pl. 36). Outside these two outer sun discs are adorants with arms raised. This interest in the sun is not seen later in the Cyclades nor was the sun the object of a cult in Crete (Nilsson 1950, 413).

The significance of symbols in this context is not clear; nor do we know why sun, sea and the female sex should be linked in this way. Its importance for us is simply that in the Early Bronze 2 period of the Cyclades an implicit religious symbolism emerges for the first time, even more clearly than in Crete.

This point is documented yet more convincingly by the Cycladic folded-arm figurines, which form a very clear and narrowly defined type. Always the arms are folded, usually right below left, always the figure is naked (except for a penis sheath and baldric on the few male figures). The nose is indicated in a standardised way by a raised ridge; few other features are shown in relief, and all share the same simplicity of style.

In the early neolithic, the standing figurine of clay already constitutes a type, and in the late neolithic the seated marble figurine with crossed legs is seen in several areas. The Plastiras and Louros types of the Grotta-Pelos culture are as closely defined in their form, but much more restricted in distribution. The Cycladic folded-arm figurine again conforms strictly to convention, and is more widespread in its distribution in the southern Aegean (figs. 19.5–19.7). It represents a significant new departure in the iconography of the Aegean. Its popularity was so great that in Crete it was actually copied, both by skilled craftsmen producing the Koumasa type, and by rather clumsy imitators, whose poor efforts occur in the Teke find (Renfrew 1969a).

FIG. 19.5 Varieties of the Cycladic folded-arm figurine and its precursors. II, Plastiras type; III, Louros type; IVA, Kapsala variety; IVC, Chalandriani variety; IVE, Koumasa variety. Scale in cm.

FIG. 19.6 Further varieties of the folded-arm figurine. IVB, Dokathismata variety; IVD, Kea variety; IVF, Spedos variety. Scale in cm.

The original meaning of these sculptures cannot be reconstructed with certainty. Although they are preserved mostly in burials, finds have occurred in settlements also—at Aghia Irini in Kea and at Phylakopi in Melos. Several examples, broken in antiquity and carefully repaired, indicate that they were not all specially made for burial, but used also by the living. Christos Doumas has argued persuasively (1969, 81 f.) that they were frequently buried simply because they were personal and cherished possessions of the deceased, and laid to rest with him.

Assuming their serious religious significance—and they can hardly be regarded as toys—they may be seen either as goddesses, actual representations of the deity, or as votaries, like so many of the figurines of the later Minoan culture. One clue is given by the series of variants on this theme—seated figurines and double figures—carved in the same style.1 The beautiful musicians from Keros are not deities, whether or not they were votaries (pl. 27, 1 and 2). And the charming seated figure offering a cup, in the collection of Mrs N. P. Goulandris (frontispiece), in its manner strongly suggests a worshipper.

The monumental size of some of these sculptures certainly does not exclude their being votaries—like the kouroi and korai of archaic Greek times. Perhaps, as in the case of the kouroi to Apollo and the korai to Athena, these votaries were in the likeness of the deity. The distinction between votive statue and cult image is not a clear one. Certainly the cult images of Late Minoan Crete were physically so unimpressive that they may not have inspired veneration in themselves, and may rather have been votive offerings to the goddess in her own likeness. In any case the creation of these impressive marble sculptures was more than a major artistic achievement: it was a consummate expression of a religious concept, a new and effective projection, influential in mainland Greece and Crete as well as in the Cyclades (pl. 31).

The individuality of the different regions of the Early Bronze 2 Aegean is well exemplified by the variety in the figurines. The Cyclades had two forms: the folded-arm figurine (with its own variants: pl. 30) and the schematic figurine of Apeiranthos type (Renfrew 1969a, 14). In west Anatolia, the schematic marble figurines of Troy, Beycesultan and Kusura type (fig. 19.4) may have survived, but western Anatolia gives very little indication of religious symbolism.

FIG. 19.7 Finds of folded-arm figurines in the Cyclades and Crete. In each case the site number is followed by a letter or letters indicating the variety of the figurines and, when several were found, the number of examples.

The varieties are indicated as follows: A, Kapsala; B, Dokathismata; C, Chalandriani; D, Kea; E, Koumasa; F, Spedos; S, Special variant (seated or double); o, unspecified; X, prehistoric copy. (For findspots, see notes to figures.)

Mainland Greece has yielded several folded-arm figurines, doubtless of Cycladic manufacture, and imitations and hybrid forms are seen at Aghios Kosmas. The only recognisable local type is the clay cone figurine (Blegen 1928, 187, fig. 177).

Crete had its folded-arm figurines, both imported and made locally (pl. 30, 3, 4 and 6). Among the possible imports is a dignified seated little figurine from Teke (Renfrew 1969a, pl. 9, a), while a double figurine in steatite from the same find perhaps imitates those now seen at Keros (Renfrew 1969a, pl. 9, b; Zapheiropoulou 1968b). It is of local work. Like the Cyclades and western Anatolia, Crete has its own schematic form in marble: the Aghios Onouphrios type (fig. 19.4). In addition, besides some very crude stone shapes at Pyrgos, there were rather simple, somewhat cylindrical figurines from Aghia Triadha, Trapeza (Pendlebury, Pendlebury and Money-Coutts 1936, pl. 18) and other sites.

Perhaps more interesting, however, as foreshadowing the terracotta bell-shaped figurines of Late Minoan times, are the anthropomorphic pottery figurines. They arc small and plump. The example from Myrtos, like a later one from Koumasa (Warren 1969c, no. 1; Xanthoudides 1924, pl. II, 41 37) and other examples, carries a jug. The Myrtos figure is exceptional for the long neck, which does indeed give it a bell-like appearance. Another, from Mochlos, has the hands immediately below the breasts (fig. 19.8; Seager 1912, fig. 34). An interesting feature of one of the Koumasa examples is that the goddess, if such she be, has a snake around her neck.

No clear indications of specific rituals emerge at this time. Possibly the magnificently decorated hearth in Building BG, below the House of the Tiles at Lerna (pl. 20, 3), the ancestor of the megaron hearth of the Mycenaean period, may have been used in some ceremonial way—but this is merely a possibility. Already, however, some of the sacred caves of Crete were revered—Arkalochori, with its dagger offerings, and Kamares perhaps, with its pottery gifts.

Only one class of object has been found whose ritual use seems well-established: the multiple vessel or kernos (pl. 11, 1). The complex circular arrangement of the example illustrated is known only from the tombs at Phylakopi in Melos. A simpler and perhaps earlier form there (pl. 11, 2) compares with a find from Koumasa in Crete (pl. 11, 3). Nilsson (1950, 137) and others have compared these with the multiple vases from Pyrgos, as well as with later bronze age successors. The stone ‘salt and pepper’ bowls have been mentioned in this connection. A striking indication of continuity is demonstrated by the offering table from Myrtos (Warren 1969c, 27 no. 8; see also pl. 26, 1 from Naxos). It finds a direct, although more finely fashioned successor at the Palace of Mallia (Marinatos and Hirmer 1960, pl. 56).

These scattered indications effectively demonstrate that at least in the Cyclades, and in Crete, a formal religious symbolism developed during the early bronze age. Moreover, the different regions had their own beliefs; the Cretan double axe and horns of consecration are not seen in the Cyclades, nor the sun, sea and sex symbolism in Early Minoan Crete. The megaron hearth is a specifically mainland feature. And yet at the same time the symbolic significance of birds, and the widespread presence of the Cycladic folded-arm figurine indicate a community of outlook, anticipated by the finds of seated, cross-legged figurines in the neolithic of Crete, the Cyclades and the mainland.

Branigan (1969b) has gathered together the Early Minoan indications which foreshadow the cult of the Snake (or Household) Goddess of Middle and Late Minoan times. He argues persuasively that the various rather separate symbols, indications of only loosely related beliefs in Early Minoan times, were consolidated during the Middle Minoan I period into the cult of the Snake Goddess. He relates this syncretistic union with the appearance of the peak sanctuaries in the Middle Minoan la period.

FIG. 19.8 Pottery vase in the form of a woman with hands supporting the breasts, decorated with white paint. From tomb XIII at Mochlos (after Seager). Height 19 cm.

It may be that analogous developments occurred in the mainland and perhaps in the Cyclades. For while the late bronze age shrine of Mycenae (with its snake) and of Aghia Irini (with its bare-breasted women) might appear to reflect aspects of Minoan religion, the Cretan idols themselves are not as impressive as these. Nor is the full complexity of the Cretan symbolism found outside of Crete.

The early bronze age societies of the Aegean evolved their own religious apparatus to cope with the supernatural world. And it was not until the partial fusion of traditions in the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation in the late bronze age that the Minoan and Mycenaean religions can be regarded as one complex and sophisticated system of beliefs. Underlying this—just as in classical Greek religion—was the earlier variety of deities and symbols, a palimpsest of beliefs which was never quite unified, and which never lost its regional variety.

Burial in the Aegean neolithic was an uncomplicated business. The simple disposal of the dead by inhumation, inside or outside the dwelling, sometimes with one or two very simple objects, was the universal practice. It is seen in the numerous burials at early neolithic Nea Nikomedeia, and in pre-neolithic times at the Franchthi Cave.

In the final neolithic the concept of the cemetery, an area outside the settlement specifically set aside for the burial of the dead, was formulated in several regions of Greece. It had, of course, been anticipated by several millennia in the Natufian culture of Palestine, and by at least a thousand years by the people of the Linearbandkeramik (Danubian I) culture. Moreover, the long barrows of Britain and north Europe, and the megalithic tombs of western Europe had been in use several centuries before the cemeteries at Souphli and Kephala were founded. The notion that monumental burial, or collective burial, or indeed burial of any kind, reached the western Mediterranean from the Aegean is entirely without foundation.

The earliest cemetery yet recorded in the Aegean is the urnfield at Souphli in Thessaly (Biesantz 1959). This is altogether exceptional for the neolithic or early bronze age of Greece in that the dead were apparently cremated (no specialist report is yet available for the remains), and the ashes placed in ‘middle-sized’ urns, sometimes accompanied by one or two additional smaller pots. The pottery is ascribed to the Larissa culture. No other cemeteries are known at present from neolithic or early bronze age Thessaly, and the practice of urn burial is not seen elsewhere in the Aegean before the middle bronze age.

The Cycladic island of Kea preserves at Kephala the first built graves of the Aegean. There, as described in chapter 5, cists either circular or rectangular in plan were constructed of small stones and surmounted by a platform of flat stones. Each contained several burials. Child burials in pithoi were also found.

The earliest rock-cut tomb yet discovered is in Attica, in the Athens Agora. Contemporary with the Kephala culture it was a shaft grave with a chamber at the bottom (fig. 7.6).

In Crete at this time the practice of burial in caves may have begun, although it is not easy to distinguish burial deposits from the purely domestic debris resulting from occupation by the living. The neolithic finds at Koumarospelio, Trapeza and the Eileithyia Cave are all of this kind, and careful excavation is needed before one can be certain of cave burial in Crete during the final neolithic period.

Already then, by the onset of the early bronze age, several features are seen which establish the pattern of burial throughout the prehistoric period in the Aegean. There is an absence of monumentality—the Aegean does not boast megaliths like those of western Europe, and the splendid tholoi of the late bronze age were built only in the later phases of Aegean civilisation. Moreover, until the late bronze age, there is a wide variety in custom between the different regions.

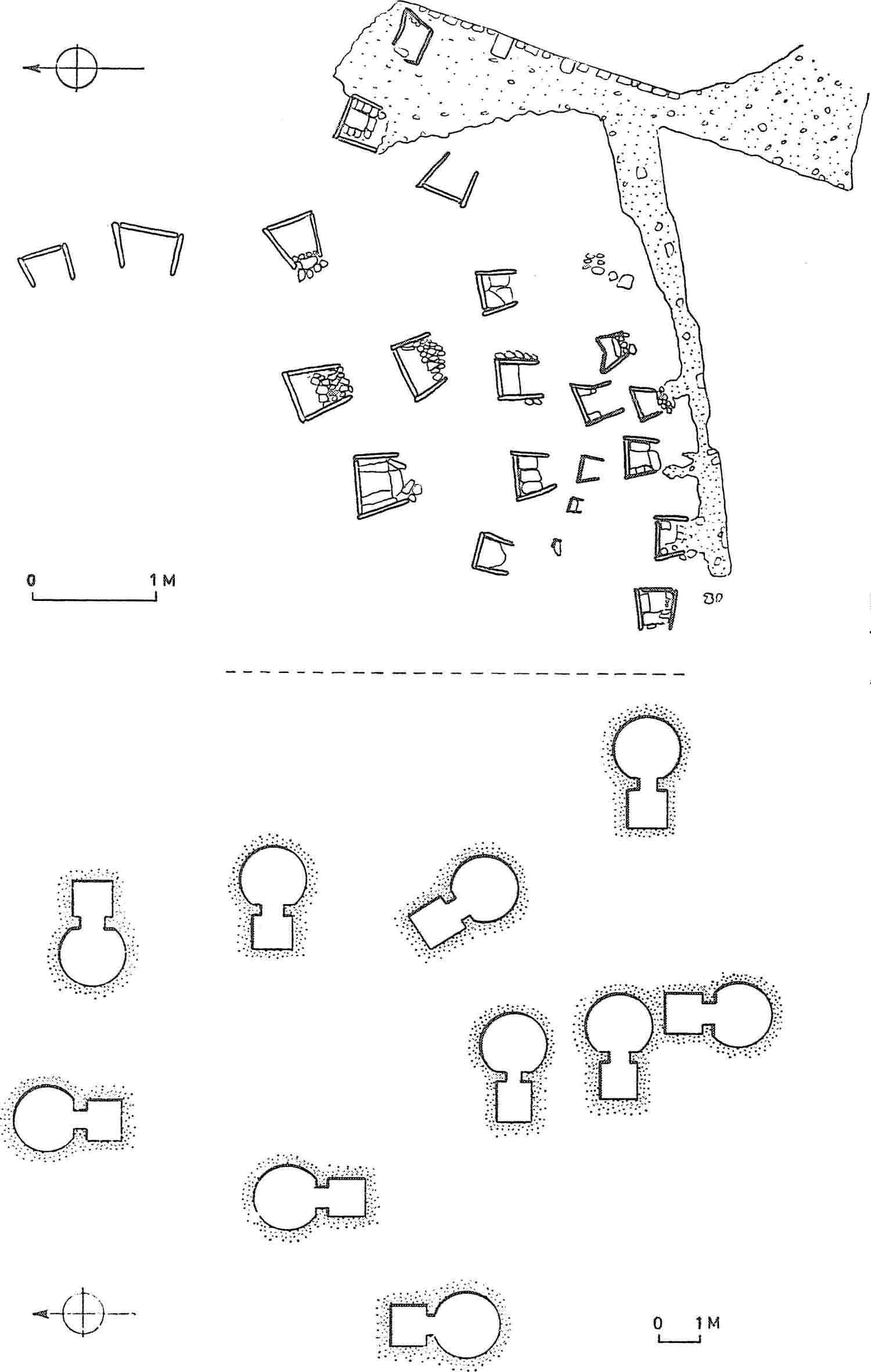

In the early bronze age the local evolutions continue. The Kephala graves are succeeded by the cist cemeteries of the Grotta-Pelos culture (pl. 25, 1; fig. 19.9) and by the built graves of the Keros-Syros culture (pl. 25, 2; fig. 19.10). Burial of one or a very few dead in cist graves is seen also at Iasos on the west Anatolian coast, and in Attica (see chapters 7 and 11) and Euboia (fig. 11.5). It prevailed, to become the main funerary form of Middle Helladic Greece.

In Crete a different tradition, of communal burial, developed. In the Early Minoan I period, and perhaps before, a settlements dead might be buried in a cave or rock shelter such as Pyrgos or Kanli Kastelli At that time, as discussed in chapter 6, the idea emerged of a built tomb to fulfil the same purpose. The round tombs of the Mesara Plain (pl. 25, 3; fig. 19.11), and the rectangular ‘ossuaries’ most frequent in east Crete are expressions of the same idea. Hutchinson (1962, 228) suggested that the dead in eastern Crete may first have been buried separately, and their bones later transferred to the ossuary, although it is possible that the dead man was laid to rest directly among the bones of his ancestors. Mylonas (1959, 118) has carefully considered the evidence from the multiple burials in the cist graves of Aghios Kosmas in Attica, and concludes that there, as on occasion in the Cyclades (Bent 1884, 42–59), the body was in some cases left outside the grave to decompose, before the bones were gathered together and set inside the grave. His arguments are persuasive, and this process of excarnation may have been practised in Crete also.

FIG. 19.9 Cemeteries of the third millennium. (Above) Aghioi Anargyroi in Naxos (after Doumas); (below) tomb group 2 at Manika in Euboia.

FIG. 19.10 Built graves of the third millennium BC.

1, lasos grave 3; 2 and 3, Orecheion Kalogries (Melos) graves 9 and 2; 4, Aghios Kosmas grave 8; 5, Chalandriani; 6, Chalandriani grave 345; 7, Mochlos tombs IV, V and VI; 8, Steno (Levkas), grave R 15.

In Crete, two or three round tombs are often found together, and this has suggested to some writers a tribal or clan structure In the society, although at Mochlos they are so numerous as to suggest family vaults. Yet the nearly two hundred burials found at Archanes exceed the total likely in a family tomb. The suggestion of some sort of clan-like division has been made also for the Cycladic cemeteries, and especially for Chalandriani in Syros, where the single graves are clustered together in separate groups (see chapter 18).

In mainland Greece also there was a variety of customs. In Levkas the deceased with his possessions was partly burnt on a funeral pyre on a circular stone-built platform up to 9 m in diameter, and the remains transferred to a pithos. This was buried in the centre of the platform which was then covered by a tumulus (figs. 19.11 and 18.2). Elsewhere cremation was not practised during the early bronze age, and the partially burnt bones found In the Trapeza Cave in Crete, and in some of the round tombs, are thought to be the result of later burning, and perhaps the fumigation of the burial place. Late in the early bronze age, cemeteries of rock-cut tombs are seen. At Manika in Euboia (fig. 7.6, 1 and 2) each grave was entered by means of a small shaft, while at Phylakopi in Melos (fig. 7.6, 3 to 6) the tomb was often cut into the hillside and entered from the front. A rock-cut tomb of the Korakou culture at Corinth suggests that there may be a continuity of tradition here from the final neolithic.

In Crete towards the end of the early bronze age there is an important development away from the altogether communal pattern of the earlier period. Individual clay coffins or larnakes are now found inside the communal tombs—as at Pyrgos for instance—and pithos burial is now seen.

No clear pattern emerges from this multiplicity of customs, other than the preference for communal burial in the Early Minoan culture. The tomb forms of the early bronze age clearly inspired those of later periods. Cist cemeteries are found in Middle Helladic Greece, evolving perhaps to the shaft graves of the late bronze age. Family rock-cut tombs became the most popular form in Crete as in Mycenaean Greece. In Crete the communal burial in round tombs continued—Kamilari II and the tomb at Gypsades were actually built in Middle Minoan II times. But the most significant new advance was the emergence of the roofed, built tomb or tholos, seen in the western Peloponnese at the close of the middle bronze age (Hood 1960; Branigan 1970b, 156). This may possibly be a development, architecturally, of the Minoan round tomb tradition, but burial, as was usually the case outside of Crete, was multiple rather than collective. This soon became the principal burial form for chiefs or princes, and the distribution of tholos tombs in the late bronze age marks effectively the extent of Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation (fig. 4.2).

The evolution in tomb form was accompanied by an increase in the wealth and quality of the grave goods. From the early bronze age onwards it seems that the deceased s most precious possessions were buried with him—his weapons, his jewellery, his drinking cup and wine equipment. Very few, If any, objects seem to have been made specially for the grave: the Early Cycladic figurines and marble objects often show signs of repair, clear indications that they were used in daily life. The same may indeed be true of the kernos vessels of Phylakopi, and the special Early Minoan stone vessels. Not until the Shaft Graves of Mycenae, with their golden ‘death masks’, the rather ineffectual gold scales and the little suit of child’s armour in gold, do we find objects possibly made with burial in mind. And even here the presumably symbolic significance of these things may have had a relevance for the living prince as well as for the dead one.

The Aegean technology for the dead does not seem to have been unduly elaborate, or particularly costly. Every community of the early bronze age set aside a special precinct for the inhumation of the dead man, who was buried together with his possessions in decent care. Not until the late bronze age is there notable ostentation, as in the architecture of the tholos tombs at Mycenae or Grchomenos (pl. 29, 2), and the Royal Tomb at Isopata in Crete. Burial did not normally involve animal sacrifice,2 and never the human sacrifice seen in the royal graves of early Egypt and Mesopotamia.

There is just a little evidence to suggest that the dead were revered or remembered after the burial—for a ‘cult of the dead’. This would imply some belief in the survival of the dead, but not necessarily in any more vital form than the dim shades of the classical Greeks. Christos Doumas has described how the cemetery of Aghioi Anargyroi in Naxos was enclosed by walls to south and east (fig. 19.9), and several curious hat-shaped vessels were found (Doumas 1962, 273 and pl. 333), which may have been used in some way on occasions other than the actual burial of the dead. Branigan (1970b, 102), in his full and careful consideration of the Mesara tholoi concluded that there was no evidence for ritual observances other than at the time of burial, and hence no clear indication of belief in an after-life. The little rectangular chambers outside the tholoi (fig. 19.11) are best regarded as ossuaries. The many cups and jars found may have been used by the mourners to drink ‘toasts’, and the animal vases to pour libations for the dead. In some cases a funeral meal was probably eaten. The paved courts seen at some of the tholoi, and most clearly at Koumasa (Branigan 1970b, 133), could conceivably, as Branigan suggests, have been used for ritual dances, but not necessarily in connection with a cult of the dead.

Similar conclusions emerge from the material excavated at the cemetery of Aghios Kosmas in Attica. Mylonas (1959, 118) has fully documented that grave goods are frequently found outside the graves, but concludes on plausible grounds that they were set there at the time of burial.

There is no persuasive evidence for a belief in after-life anywhere in the Aegean. Very possibly the heavy slab covers on some Cycladic graves—already seen at Kephala—may have been intended to keep the dead from rising, just as the heavy stones at the doorway to some of the Mesara tholoi. The position of the knees, up towards the chest in a crouched position, suggest that some of the Cycladic corpses may have been tied, and a possible motive again would be to prevent the dead from waking. There is no necessary contradiction here: fear of the dead does not necessarily imply a belief in immortality. Nor do the finds from the late bronze age Aegean demand a different conclusion. Numerous cups and other broken vessels in the dromoi of Mycenaean tombs suggest the likelihood of libations and funeral feasting, but not on occasions subsequent to the burials. Hero cults, documented by Nilsson, involved the veneration of specific heroic figures receiving some of the honours accorded to minor deities: this is not the same thing at all as a cult of the dead.

FIG. 19.11 Cemeteries of the third millennium BC. (Above) tholos tomb A at Platanos in the Mesara Plain, Crete; (below) the ‘R Graves’ at Steno in the Plain of Nidri, Levkas.

The identification of the actual religious beliefs and customs involved in burial in the Aegean early bronze age is more difficult (cf. Ucko 1969), if not impossible. Nothing is gained by over-simplifying, by lumping all religious and funerary observances together as directed towards a single ‘Great Earth Mother’. As Nilsson (1950, 391) remarks: ‘We must have due regard to the differences between the deities, and not obliterate them.’

This brief summary shows that the observances for the dead were neither very complicated—so far as the archaeological remains show—nor very expensive. The Cycladic cist graves might have taken a couple of men a day to construct. The built graves of Crete took considerably longer, but they contained numerous individuals. Rock-cut tombs probably required proportionately more work, but in general the graves of the early bronze age represent a labour equivalent of little more than a total of a man-week for each occupant. It was the fusion of the Cretan practice of building large stone tombs with the mainland and the Cycladic one of burying only two or three people in each, which yielded the prodigiously expensive construction of the late bronze age tholos tombs. They must have occupied a team of men for some weeks or months, and yet were occupied by very few individuals.

The overwhelming archaeological significance of burial in the Aegean area arises from the custom of burying many of the deceased’s most prized possessions with him. Many of archaeology’s richest finds are objects thus consigned to ‘the silent earth.’ It is we, not they, who attach such Importance to these burials. Until the great tholos vaults of the late bronze age the prehistoric Aegean cemetery was probably much like the Greek village cemetery today: respected, hallowed indeed, yet modest and left chiefly to the dead.

The importance to all men in all cultures of play and playing was emphasised by Huizinga (1949, 173) who viewed civilisation sub specie ludi: ‘Civilisation is, in its earliest stages, played. It does not come from play, like a baby detaching itself from the womb: it arises in and as play, and never leaves it.’ Certainly the culture-historian must take seriously a whole range of activities, neither evidently productive in themselves (in the sense of fulfilling primary needs), nor of obvious religious significance. Play can be a serious matter. All these projections—the art-work, music, the patterns of dance and game—often seem to give symbolic form to pleasure itself: pleasure reified.

Song, dance and play leave hardly an echo in the archaeological record. But at least the Harvester Vase (pl. 27, 3) gives us a most vivid glimpse of rural gaiety in the late bronze age, with musical background from the sistrum. More sophisticated evidence comes from delightful terracotta groups of dancers found near the tholos at Kamilari, and at Palaikastro (Marinates and Hirmer 1960, pl. 132). The circular dance is still the most popular today in Greece, and In weddings of the Orthodox Church, the bride, the groom and the priest circulate in solemn dance around the altar. Many ancient Greek rituals and festivities also included dances, and It is safe to assume that people danced for pleasure, as well as in connection with religious celebrations, already in the early bronze age. Certainly the little Cycladic sculptures (pl. 27, 1 and 2) document delightfully that music was available—both from a stringed instrument whether lyre or kithara, and from the double pipes. A figurine without provenance, standing like the piper, is playing a syrinx (Cahn 1965, no. 28).

FIG. 19.12 The lyre: ivory sound box from Tomb 7 of the Late Minoan cemetery at Zapher Papoura (after Evans). Length 25 cm.

In late bronze age times there are several representations of the lyre, and a grave in the Zapher Papoura cemetery actually contained the ivory remains of one (fig. 19.12). Evidently the deceased was an accomplished player, and the notion that he was a professional minstrel is tempting. The gold ring and gold beads also found indicate his high standing in Minoan society at the end of the bronze age.

Royal play is indicated by a magnificent gaming board from Knossos (Evans 1921–35, III, frontispiece). Clearly too, in late bronze age times, and especially on the mainland, hunting was a popular occupation. Inlay work on Mycenaean daggers suggests that already it was the sport of princes.

The most famous of all Aegean sports was the Cretan bull-leaping. It is depicted in numerous scenes on gems and frescoes, in small sculptures and in bronzes. Graham has persuasively argued that It used to take place in the central courts of the palaces, doubtless before crowds, such as are seen in the miniature frescoes. Whether or not it had a religious origin and significance, which is not certain, these representations are entirely secular in flavour, expressing often the dramatic contrast in the anatomies of bull and leaper. The miniature frescoes also direct attention to the social aspects—the crowd, the setting—rather than focusing too intensely upon the central activity. No Early Minoan bull-leaping scenes have been preserved, but we have several theriomorphic vases, where the tiny figure of a man is grasping the horn of the bull. Examples come from Koumasa and Porti, and the bull sometimes wears a kind of harness (Xanthoudides 19245 pl II, 4126; pl. VII, 5052. For harness, ibid., pl. VII, 5052; Seager 1912, fig. 29). Evidently the bull sport had an origin at least as far back as the early bronze age.

Inevitably evidence for music, dance and sport is scanty in the material record. But fortunately finds are sufficiently numerous to document the transformation, during the third and early second millennia BC, of the simple and rather crude artistic conventions of the Aegean neolithic to the sophisticated elegance of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation.

Works of art of the Aegean early bronze age are now so numerous that no survey can be complete. It is possible, however, by selecting a few themes, to indicate how rapidly the expressive powers of artists and craftsmen in the third millennium developed. The created visual environment now became the product of conscious design, especially in the palaces. Decoration, with the use of symbolism and of natural images, enjoyed a much wider potential range of meaning.

The forms of expression of the neolithic, at least those which have been preserved, were rather limited. Pottery generally had complete axial symmetry, and decoration, with a few exceptions during the early neolithic was restricted to linear ornament, whether painted (usually in monochrome), Incised, or occasionally applied. Figurines were moulded from clay, and more rarely carved in stone. Stone and shell were used for simple beads and bracelets. Probably the most beautiful and carefully worked household objects were the few stone bowls which have been found from the middle neolithic onwards.