The foregoing chapters have shown how the culture sequence in the third millennium BC may independently be established for Crete, for southern Greece and for northwestern Anatolia. The Cycladic sequence has not been subjected to any detailed examination in recent years. Eighty per cent of the available Early Cycladic material was excavated before 1910, and no comprehensive attempt at a synthesis has been made since Åberg’s work in 1933. The material is particularly abundant, and derives chiefly from graves. The lack of finds from settlements means that there are few stratigraphical sequences of any kind, and several writers have thus felt free to impose their own Early Cycladic I, II, III arrangement on the material, purely by analogy with the Cretan or mainland systems.

With the wealth of rather exotic finds, and the considerable flexibility in their assumed chronological position, the region has become a sort of lucky-dip for hunters after cultural parallels, and there is scarcely an early bronze age site on the coasts of the Aegean or indeed of the Mediterranean where Cycladic influence has not been suggested often on the flimsiest of evidence. It is frequently felt to be sufficient for the suggestion of cultural connections that two objects found at distant places should show some similarity of form, without a detailed consideration of their respective contexts, or even of the chronology

The aim here is to define precisely and describe in some detail the principal groups of material in order to provide a framework from which such comparisons can be made. As Indicated in chapter 4, a nomenclature whereby the material is divided into ‘cultures’ on the basis of recurrent associations is preferred to the use of terms such as ‘Early Cycladic I’ and so on.

The concept of type is used here without further analysis: one of the most striking features of the Early Cycladic finds is the way they do in fact fall into types. Of the many hundred pots known from graves of what has been termed the Pelos group, there are really only four shapes. And time and time again when a supposedly unique form is published, other examples turn up to show that it may be regarded as a type. Thus the seated ‘harpist’ from Keros is closely paralleled by two from Thera (pl. 27, 2), and by three fragments from Naxos (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pl. 79). A curious eared figurine with prominent kneecaps (pl. 2, 2 and 3; Tsountas 1898, pl. 10, 4) can now be called the ‘Plastiras type’ after several finds by Doumas at the site of that name in Paros. Again the striking green handle of stone published by Blinkenberg (1896, 48) finds parallels at several sites in Naxos, notably near Aghioi Anargyroi. So that, while a detailed analysis of the artefacts into trait clusters might be intellectually more satisfying, there can be little doubt that the result would be much the same as the direct and intuitive division into types which is adopted here.

The only well-stratified settlement site of the third millennium in the Cyclades is Phylakopi, excavated under the day-to-day direction of Duncan Mackenzie (Atkinson et al. 1904; Mackenzie 1963). The important settlement of Aghia Irini in Kea does also have deposits of this period beneath the more ample finds of the later bronze age, but present indications are that the finds relate more closely to those of the mainland than of the Cycladic islands (Caskey 1964b). And the settlement of Paroikia in Paros is predominantly of the later bronze age also (Rubensohn 1917). Most of the important excavated settlements in the Cyclades are single period or unstratified sites, such as Chalandriani in Syros (Tsountas 1899; Bossert 1967), Dhaskalio in Keros (Doumas 1964) and those in south-east Naxos (Doumas 1963; 1964).

The available material comes principally from the cemeteries, chiefly from the early excavations reported by Bent, Dümmler, Tsountas, Edgar, Stephanos and Varoucha. In recent years there have been further important cemetery excavations, notably by Doumas.

Perhaps for this reason there is considerable confusion in the literature concerning the sequence and date of the Early Cycladic material. Most writers since the time of Kahrstedt, including Childe and Åberg, have distinguished a Syros group and a Pelos group—terms usually not well defined. It is not always clear whether or not these are considered to be contemporary. Moreover, while Weinberg (1954, 96) on the one hand has seen in the stamped spirals of the Syros group a synchronism with the Dhimini culture of Thessaly, Åberg (1933,74) correlates such decoration with the Shaft Graves of Mycenae, at least a millennium later.

Åberg indeed placed many of the Cycladic graves in a middle bronze age context, appealing to a supposed lack of other material in that period, a lacuna now amply filled by the work of Scholes (1956). His arguments misled even Childe, and in them unfortunate prominence is given to two finds. One of these is a grave at Aghios Loukas in Syros containing a Minyan ware bowl, a jug and an incised pyxis (Tsountas 1899, pl. 6, 24 and 27). There is no reason to class it in the Syros group—the pyxis, which is conical, resembles rather those of Phylakopi I, of which it may indeed be a late version—and the find is entirely without chronological significance for the Early Cycladic graves. He lays weight also on the middle bronze age affinities of the Amorgos finds, which for some reason are placed in his Pelos group. The finds do indeed have Middle Minoan relations, but this need not cause any difficulty, for the Amorgos group, as will be seen below, can be set at the end of the Early Cycladic period. Åberg’s difficulty was increased by his doubts on the Phylakopi stratigraphy (1933, 110 f), which left him without any framework for the material. It is only with his acceptance of the appearance of Cretan Kamares ware in the Second City of Phylakopi that one finally feels on firm ground.

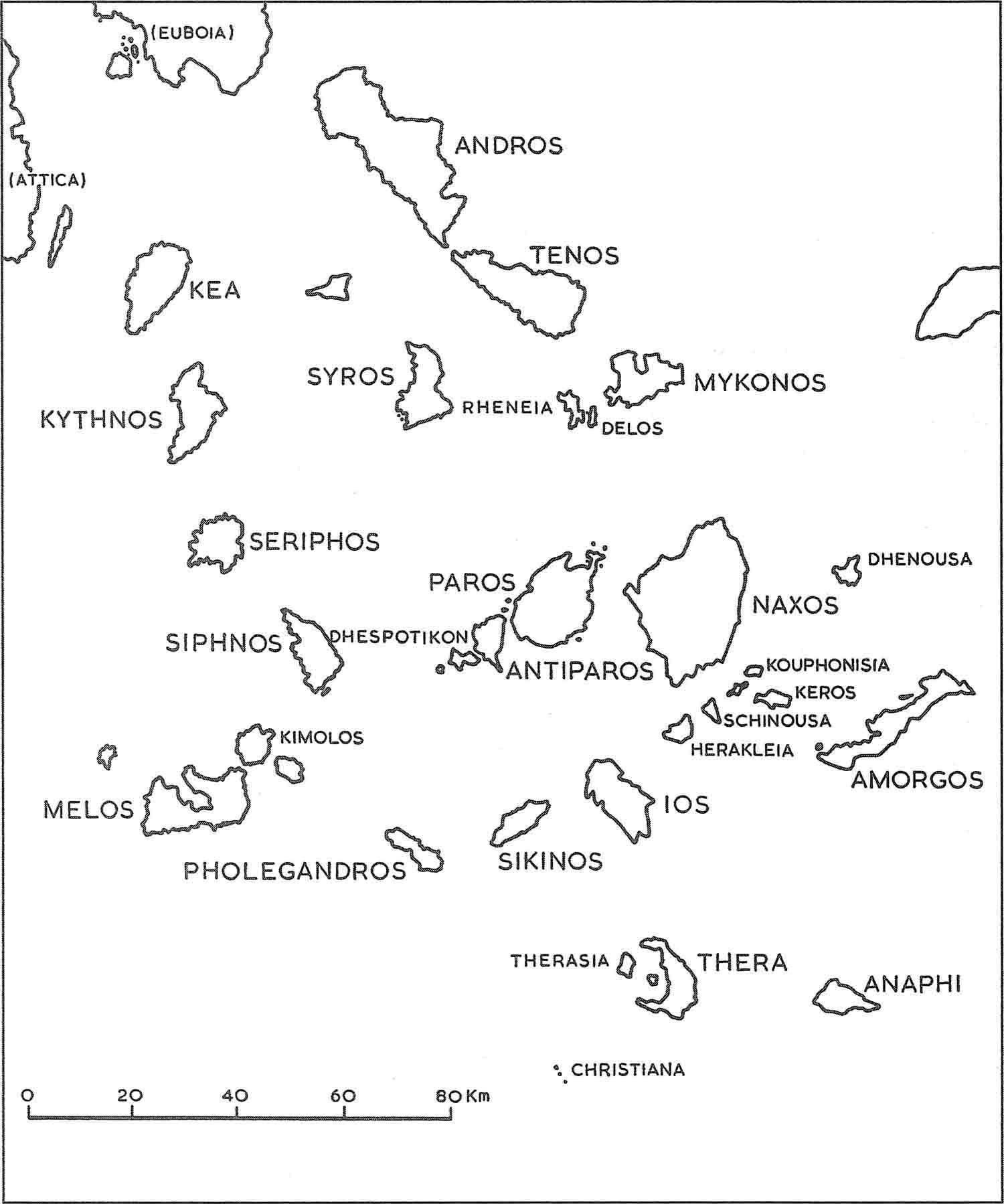

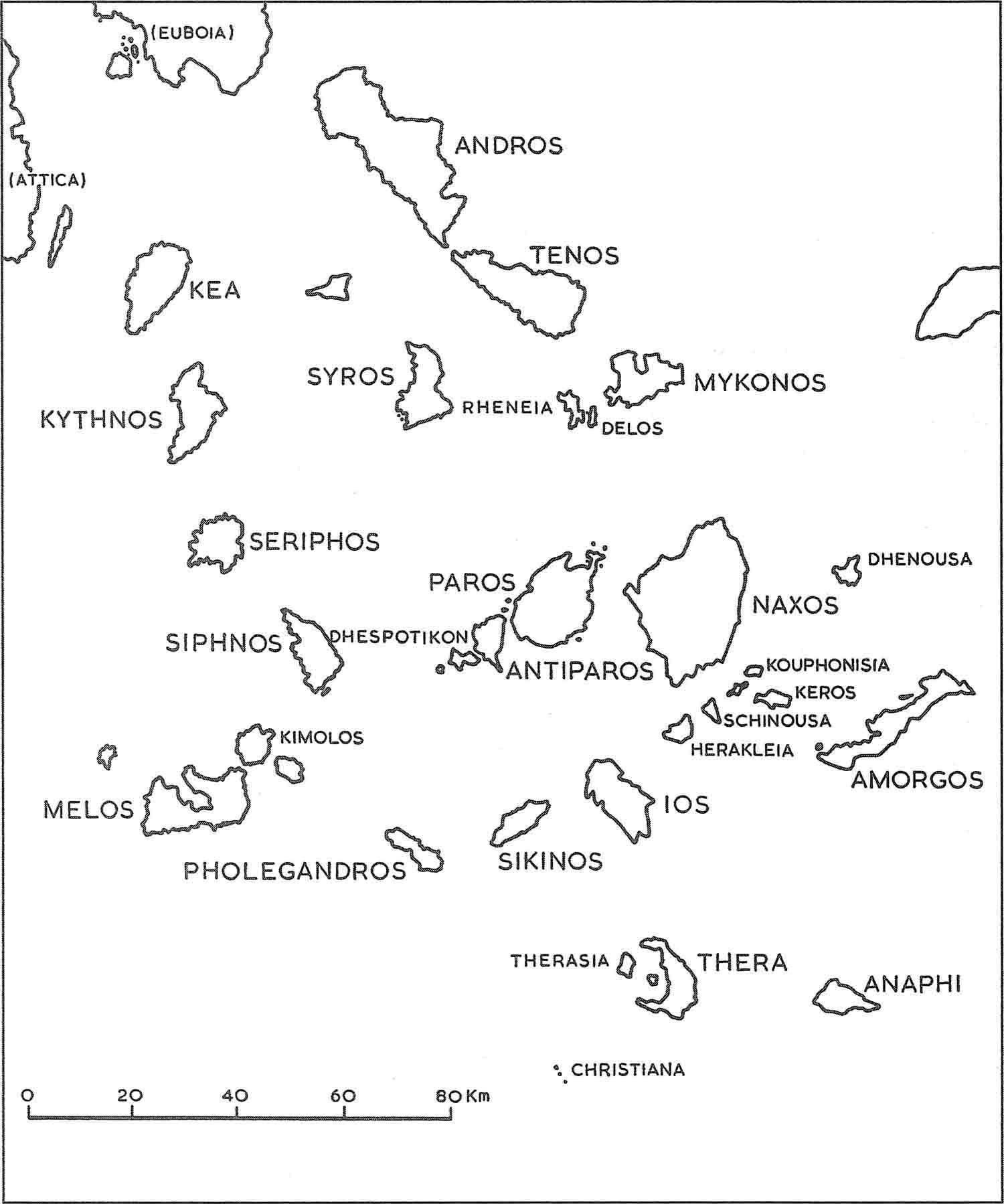

FIG. 9.1 The Cycladic islands.

Without undertaking further excavations at early bronze age sites in the Cyclades—and this the writer has not yet been able to do—the research worker has three major sources of information bearing on the chronology of the period in question. The first of these is such stratigraphic evidence as may be available, which comes chiefly from a single site.

The known sites, and especially the cemeteries, in the Cyclades are now very numerous. Their location, and the surface observations made at them can provide a second potential source of information. And thirdly the association of the finds within individual graves in the cemeteries has in many cases been recorded. The results yielded by these three approaches will now be presented.

Phylakopi is the only well stratified site III the Cyclades, and its excavation by the British School in 1896 to 1899 has rightly been hailed by Blegen as ‘the first really serious effort to understand stratification, the first really good excavation in Greece’. The publication (Atkinson et al. 1904) was in many ways ahead of its time, but it was a joint work by several writers, and minor inconsistencies do occur, although Åberg has perhaps made rather much of them (1933, 25). There is really no disagreement in the work about the basic sequence of three cities, preceded by an earlier phase. Both Edgar and Mackenzie agree that the pottery styles may be correlated broadly with these building phases, and there is harmony too on points of detail—such as the persistence of the ‘geometric’ painted ware, frequent in the First City, into the early phases of the Second City. But on matters of interpretation, such as the question of ‘catastrophes’, there is certainly disagreement.

Åberg was in a sense right to ask for corroboration of these statements—which are often no more than undocumented assertions—and in the absence of adequate evidence to take a sceptical position. But the situation has been transformed by a study of the admirable and scrupulously factual Daybooks kept by Mackenzie (1963) throughout the excavation of the site. The late Mr R. W. Hutchinson kindly drew attention to their existence in the possession of the British School at Athens. With the permission of the School a typewritten transcript has been made of the Daybooks, and this provides the basic documentation of findspots which is necessary to substantiate the published conclusions. It certainly supports most of these, although Mackenzie’s finer subdivisions are perhaps a shade elaborate (Atkinson et al. 1904, 248 f). Blegen has suggested that he was influenced by the Cretan classification which was being worked out, with his own collaboration, at the time he was writing his Phylakopi chapter.

Of course many terms have changed in meaning: ‘Early Mycenaean’ was often applied to middle bronze age material, and ‘Minyan ware’ was not so termed at Phylakopi until the excavations of Dawkins and Droop (1911). The essential picture, however, is clear, and the very sound steps in stratigraphical reasoning—then at an early stage—are of considerable interest in themselves.

It is perhaps useful too, in assessing statements made—not all of which are acceptable today—to distinguish between the recording of opinions and actual observations. The latter give a picture wholly consistent with the basic threefold division, while the former must sometimes be altered in the light of new evidence. The whole sequence is so obviously validated in the Daybooks that it is not proposed to give here a detailed analysis of them.

Reference has been made elsewhere (Renfrew 1965, 61) to passages in the Daybooks where a sound threefold stratigraphy is recorded. It is clear that First City material was frequently found in good association. The diagnostic importance of incised wares, notably the conical pyxis and the duck vase (pl. 12), is underlined. Together with these were found the geometric’ painted ware including the beaked jug (pl. 10, 2), the Melian bowl, the one-handled mug and the kernos (pl. 11, 1). It is clear too that the First City was occupied prior to the construction of the town wall, and that it was followed by the fortified Second City (pl. 21, 3) in which closed deposits were also found. These included imported Kamares ware. For these and other statements the Daybooks give detailed corroboration which supplements the presentation in the final excavation report.

Absolutely crucial to the Early Cycladic chronology is the careful account given in the Daybooks of the stratigraphical dig in squares JK1–2 (Mackenzie 1963, DB 1898,12). There the finds of pre-City material are described in some detail, notably the simple burnished ware, often with tubular lug handles (pl. 4, 8), and pithoi with raised bands bearing incised decoration. These shapes, identifiable today among the preserved finds, provide the best documented occurrence of the domestic material of what we shall call the Grotta-Pelos culture.

The terms ‘Phylakopi I’ and ‘Phylakopi II cultures’ are proposed for the finds of the First and Second Cities respectively. They are defined and discussed in chapter 12 and in the next section. The term Phylakopi O, or pre-City, will be used for the ‘primitive material’ from the lowest levels of Squares JK 1–2. It has been possible to study all the material from Phylakopi that is preserved in Melos, Athens and Oxford, and a clearer picture of the pottery of these cultures can thus be painted than is possible from the original publication.

The Phylakopi stratigraphy gives us two clear groups of material of relevance to the early bronze age, and this fact must be the starting point for a relative chronology. But it does not follow that these two cultures cover the entire period, for the remains there prior to the First City are very scanty and not really very fully recorded. It will be argued in chapter 13 that Phylakopi I is partly contemporary with the middle bronze age of the mainland—a typical duck vase, for example, was found in Middle Helladic Eutresis (Goldman 1931, 184)—and with the Early Bronze Age 3 phase of Anatolia. Equally the Phylakopi O wares are closely paralleled in the Kum Tepe lb material of the Troad. This precedes Troy I and is thus contemporary with the mainland final neolithic. Between the two may be something of a gap. It may well be of significance that fragments of a painted mug, apparently of Syros type (cf. pl. 7, 4), were found in the twelfth half-metre of Square JI (Atkinson et al. 1904, 86). This is a level above most of the Phylakopi O material and lower than that of Phylakopi I, so that the find does support the position of the Syros group chronologically between Phylakopi O and Phylakopi I. Moreover several vessels described in Edgar’s pottery class 2 (ibid., 85–87) resemble Syros forms. Some of the plain burnished wares from the West Cemetery also (pl. 8, 12–13), which do not conform either with the First City or pre-City material, may fall into this intervening period.

In addition several folded-arm figurines were found at Phylakopi (pl. 8, 1–3), and it is argued below that this type is of Keros-Syros date. It should be observed that the schematic Phylakopi I figurines (pl. 8, 6–8) are not to be connected with the schematic form of the Paros and Antiparos cemeteries. They seem rather, like the schematic shouldered ones of Kea, to be of Phylakopi I or even middle bronze age date.

It is possible therefore to make a number of statements and suggestions on the basis of the Phylakopi stratigraphy, but a clear idea of the period can be obtained only by taking the cemeteries into account.

For the present purpose this middle bronze age culture is of interest In so far as It provides a chronological fixed point, before which the Phylakopi I culture and the entire early bronze age must be set.

It is characterised by matt-painted ware (pl. 13, 3), with black curvilinear decoration on a chalky white or yellow ground which contrasts in fabric and in style with the Phylakopi I painted wares. This ware is found at Phylakopi exclusively In the Second City. At this time the fortifications were first constructed (pl. 21, 3). Such wares have been found at Akrotiri in Thera (Åberg 1933, 133), at the Paros acropolis (Rubensohn 1917, fig. 68) and at Grotta in Naxos (pl. 13, 1). Outside the Cyclades they are documented both at middle bronze age Lerna (Phase V: Zervos 1957, pl. 284–86) and at Knossos (pl. 13, 2) where they occur in a dear Middle Minoan Ib context.

Minyan ware is seen at Phylakopi (pl. 13, 5–6), principally in the Second City (Dawkins and Droop 1911, 17) and it certainly does not occur earlier. Considerable quantities of Kamares ware have been found (pl. 13, 4) and Mr Sinclair Hood has kindly Indicated that it includes both Middle Minoan IIa types and examples which he would include in his revised classification of Middle Minoan Ia (see chapter 13).

It is thus possible to set the beginning of the Second City, and the first fortification of Phylakopi, as contemporary with the Middle Minoan Ia period in Crete, and with the earlier middle bronze age of the mainland. This important result of the Phylakopi excavations has considerable value for the chronology of the Cycladic early bronze age, and is utilised in chapter 13.

Following this re-examination of the Phylakopi sequence it seemed useful to visit all known prehistoric sites in the Cyclades, and to search for new ones. The results of this survey are briefly summarised in the Gazetteer (Appendix 1). Many of the locations are known solely through the discovery of cist graves: at others, traces of settlement have also been found. One by-product of this search was the identification as a neolithic site of Saliagos in Antiparos (Belmont and Renfrew 1964), and the consequent recognition, as a result of excavations there (Evans and Renfrew 1968), of a distinctive neolithic culture in the Cyclades, to which reference has been made in chapter 5. The sites in the Gazetteer are classed, where possible, into the cultures defined in this chapter: Grotta-Pelos, Keros-Syros and Phylakopi I. But for the moment it is sufficient to accept that neolithic and later bronze age sites can be identified rather readily. The cist grave cemeteries belong to the early bronze age.

One important consequence of the surface survey was the equation of material found at two important early settlements with part of the material from the cemeteries designated by Childe and Åberg as the Pelos group. This relationship with the settlement material is of great interest.

The simple burnished wares of Phylakopi O were already compared by Edgar (Atkinson et al. 1904, 82 f) and by Mackenzie (1963 [DB 1898, 22]) with the finds from the cemetery at Pelos in Melos. These last have given their name to an important series of finds from cemeteries in several of the islands. But it may be that the Phylakopi O and Pelos finds were rather hastily equated and, while the conclusion is supported here it seems wise to substantiate it in more detail.

Fortunately it has been possible to study some of the material from Phylakopi which, although unlabelled, may be recognised from Mackenzie’s descriptions as coming from the Phylakopi O layers. Prominent are rounded bowls of thick burnished ware (fig. 10.1, 10–13; pl. 4, 7). Some of these have thickened rolled rims. The principal handle form is the horizontal lug, pierced or unpierced, but ledge handles also recur, as do ‘cheese pots’ (fig. 10.2, 1–6).

Exactly this assemblage of forms (fig. 10.1, 1–3) is preserved in the museum storerooms of Naxos, deriving from Welter’s excavations at Grotta, and there termed by him (Karo 1930, 134) ‘sub-neolithic’. The material is described and illustrated in chapter 10 and Appendix 2 (fig. 10.2, 7–12).

We are faced therefore with two homogeneous groups of material: that from the Pelos-type graves of Melos, Paros, Antiparos, Naxos and Siphnos, and the ‘sub-neolithic’ finds from Grotta and Phylakopi O. None of the domestic wares has been found in the cist graves, with the exception of an oblong bowl with a horizontally pierced lug handle from a grave at the cemetery of Pelos in Melos. At first sight therefore it is not obvious why the two should be grouped together, for on a strict application of Childe’s definition they would fall in separate cultures. But as will be seen, a number of arguments lead us to believe that the two assemblages were in use at the same time and by the same group of people. It seems, however, that the incised decoration applied to pyxides and so forth was used chiefly for funerary vessels, so that examples are scarcely met with in the settlements.

Fortunately just a few of the grave forms have been found in the settlements at Grotta and Phylakopi. From Phylakopi comes an incised pyxis lid (pl. 4, 10; Zervos 1957, pl. 84) which differs in shape and decoration from those of the Phylakopi I culture (pl. 10, 5), as well as marble bowl fragments of a kind seen in the graves, and fragments in both clay (pl. 4, 9) and marble of the footed vessels familiar from the cemeteries (pl. 3, 5; cf. Mackenzie 1963 [DB 1898, 22]). Similar finds come from Grotta, where they include several ‘frying pan’ fragments of the type found entire in a grave at Kampos in Paros (Varoucha 1926, 107).

More convincing evidence perhaps than these finds is provided by the discovery of several more early settlements, adjacent to the Pelos group cemeteries, during a recent survey. These were identified by surface finds and provide examples of the Phylakopi O-Grotta domestic wares which are lacking in the graves themselves. The typical rolled rim (pl. 4, 2–6) has been found on settlements adjoining the Pelos cemeteries at Pelos itself, at Aghioi Anargyroi and Ana in Naxos and on the Epano Kouphonisi, ledge handles at Pelos, Aïla and Kastraki in Naxos and Akrotiraki in Siphnos, and incised-cordon pithos fragments at Ana, Kastraki, Akrotiraki and Cheiromylos in Dhespotikon. The finds from some of these cemeteries are exclusively of Pelos type, and an equation between the domestic and funerary material seems inevitable. The term Grotta-Pelos culture is proposed for all this material together. It is further discussed in chapter 10, together with the evidence from outside the Cyclades which tends to support the association.

A very few graves from the Early Cycladic cemeteries contain types of what we have defined as the Phylakopi I culture. In the first instance, of course, there are the tombs from Phylakopi itself (Atkinson et al. 1904, 234). And in addition a few of the cist graves on Amorgos contained duck vases (pl. 12, 6) and other shapes of the culture (Dümmler 1886, Beilage A).

In general, however, the material is very different from that of the Phylakopi I culture. It has been divided in the past, and with good reason, into two broad groups, sometimes designated ‘Pelos’ and ‘Syros’, after the excavated cemeteries of Pelos in Melos and Chalandriani in Syros. It is indeed clear, on inspection of the material, that the finds from these two cemeteries have few resemblances. In 1965 it was possible to show, without a formal quantitative treatment, that two distinct groups of material can indeed be defined which do not normally occur together in the same grave, although they may both be found in the same cemetery (Renfrew 1965, 67).

This informal assessment can now be set upon a more systematic basis. Ideally one would wish to compare systematically the finds in each grave with those from every other. On the assumption that the graves whose contents are most closely similar will be most closely related (whether in time or in terms of cultural affinity) it should be possible to organise the material in such a way that the most closely similar graves are placed together. The graves should then be arranged in a meaningful order, significant chronologically (or in terms of whatever other variable is responsible for the variations observed). This is, of course, the procedure known as seriation, invented in the last century (Petrie 1899) and set upon a more systematic basis by Robinson and Brainerd in 1951 (cf. Kendall 1969).

Unfortunately some of the graves are so meanly furnished with goods that they show no similarities, although they could be exactly contemporary, and representatives of the same cultural group. For example:

Grave 1 might contain the types A B C D E F G H I J K L

Grave 2 might contain the types A B C D E F

Grave 3 might contain the types G H I J K L

Grave 4 might contain the types A B C G H I

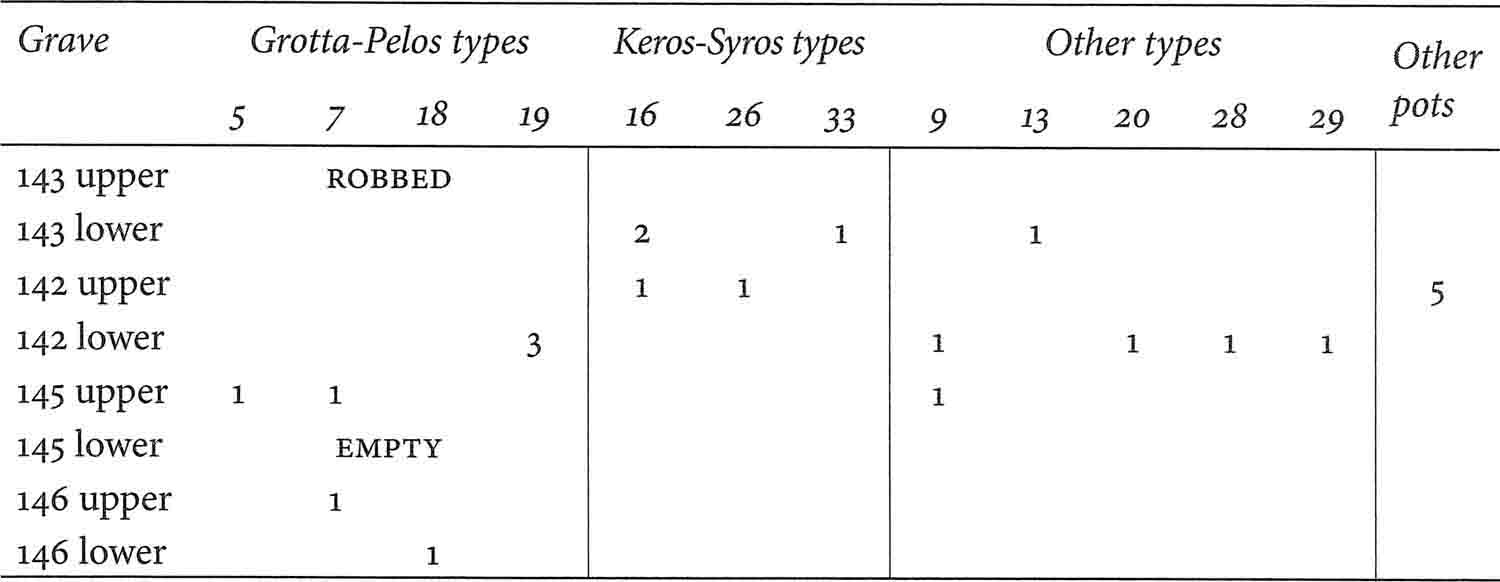

Grave 1 may be a rich grave of a given date, and graves 2 to 4 poorer graves of the same culture and date. Yet graves 2 and 3 are totally different in terms of their contents. The poverty of grave goods in some of the burials is well seen in table 9.1.

It was therefore found necessary, instead of considering and comparing individual graves, to take the entire cemetery as the operational unit under consideration. For the present purpose all the finds from a given cemetery are thus considered to be associated together. It remains true that cemeteries used for the same short period of time may be expected to contain similar grave goods (if they belong to the same cultural group). And cemeteries of different periods will be different. But clearly cemeteries of long duration may show similarities both with the early cemeteries and the late ones.

The work here described was carried out in collaboration with Gene Sterud of the University of California at Los Angeles. A by-product of this research was the invention of a new and rapid method, close proximity analysis, for handling material in this way. An account of it has already been published (Renfrew and Sterud 1969). Mr Sterud has kindly agreed to my giving here a fuller account of our work on the Cycladic cemeteries.

The first step was to tabulate the grave goods found, on a cemetery-by-cemetery basis. Fortunately the writings of Tsountas, Papathanasopoulos, Edgar and Varoucha give sufficient detail of the associations to permit this. The resulting incidence matrix (i.e. table of finds by cemetery) is given in table Appx. 3.1.

After the compilation of such an incidence matrix, the next step is to compare each cemetery with every other cemetery, in terms of the finds made at each. This can be done in two different ways.

The simplest procedure is to produce a presence-absence similarity coefficient matrix. For example, cemeteries A and B will have a similarity coefficient of 5 if they have five types mutually in common, irrespective of the number of times these types occur at each cemetery. The resulting matrix, constructed with the aid of edge-punched cards but without the use of computer facilities (Renfrew and Sterud 1969, 273, Table 3), is seen in table Appx. 3.2.

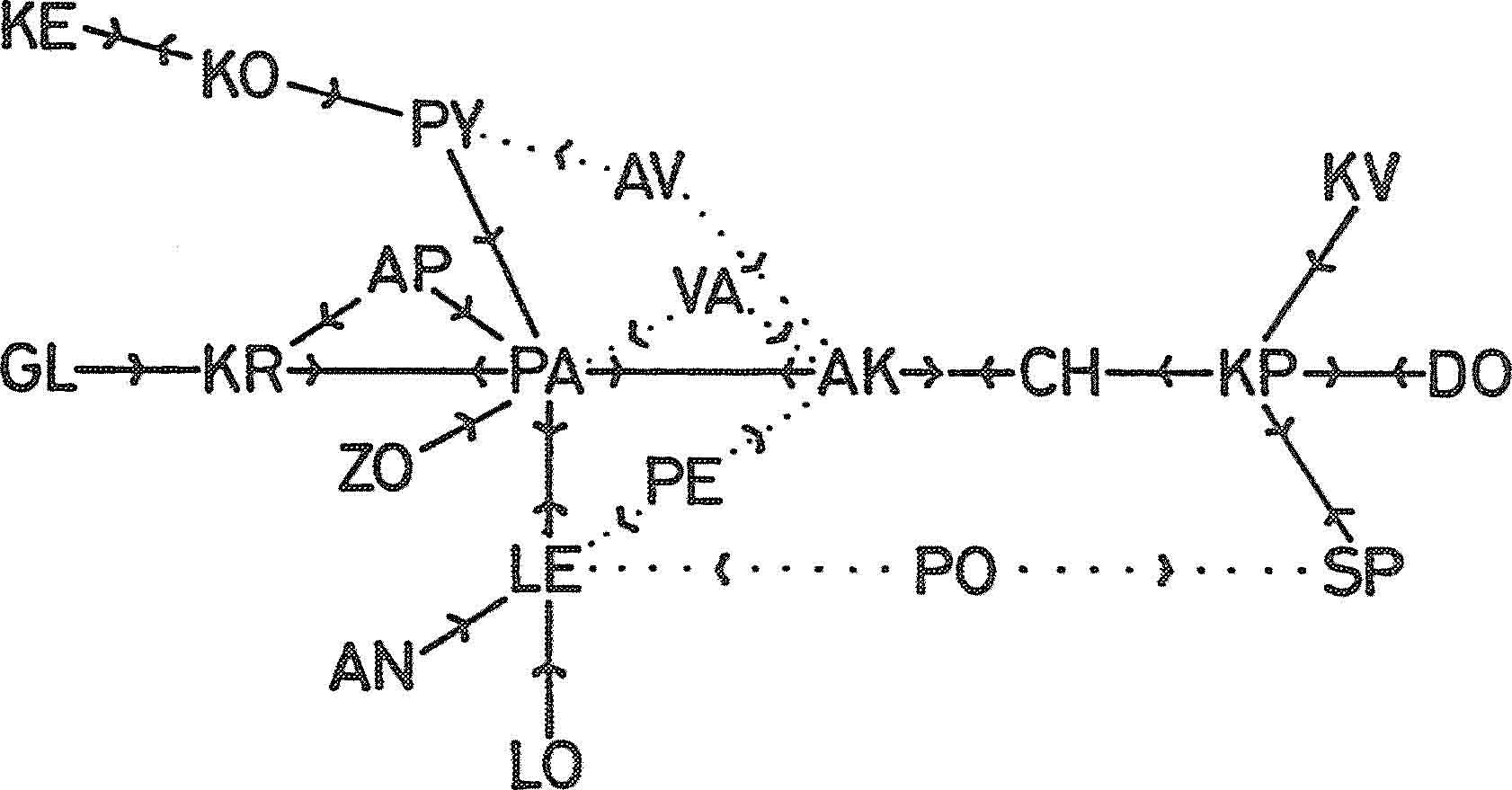

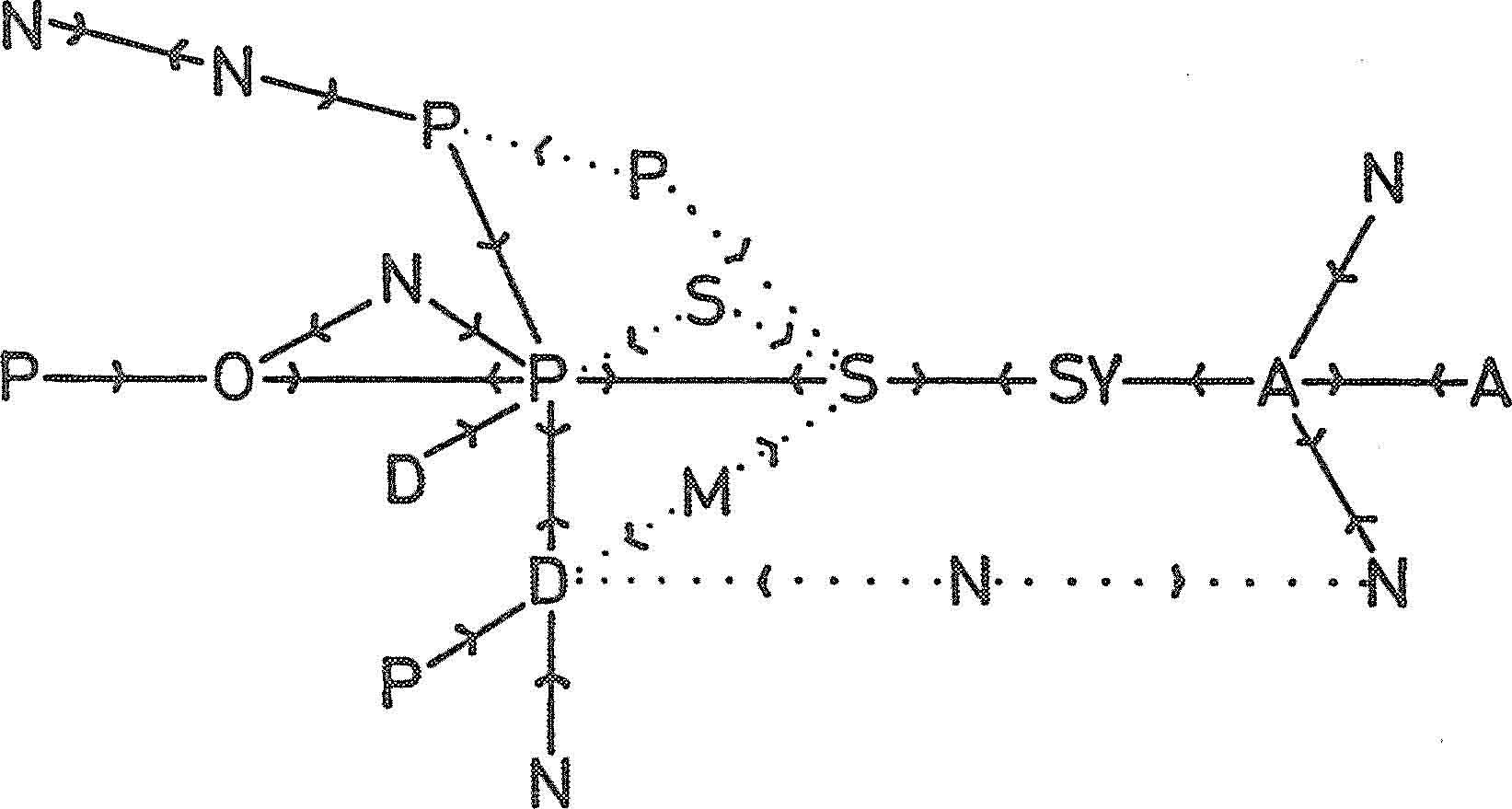

The new ordering procedure, close-proximity analysis, allows the cemeteries to be arranged rather quickly, and without the aid of a computer, into the diagrammatic form given below. Adjacent cemeteries in the diagram are closely similar to each other, and the arrangement is based solely on such similarities. The diagram can thus be used as a basis for the classification of cemeteries. It is at once clear that the cemeteries formerly described as of Syros type (Chalandriani, Spedos, Karvounolakkoi, Dokathismata and part of Akrotiraki) are distinguished neatly from those formerly designated as the Pelos group (fig. 9.1).

FIG. 9.2 Close-proximity structure for the Early Cycladic cemeteries, using presence-absence similarity coefficients (table Appx 3.2). Coefficients less than 2 have been discounted. (For abbreviations see Appendix 3).

An alternative procedure is to compile a similarity coefficient matrix of Robinson-Brainerd type (see table Appx. 3.3). Here the types present at a cemetery are first indicated by percentages in the incidence matrix. Thus a cemetery with three examples of type X and one of type Y will score 75 per cent for X and 25 per cent for Y. The similarity coefficient between this cemetery and another is calculated as Robinson described (Brainerd and Robinson 1951, 295). On this basis, the number of occurrences of a given type in a cemetery, and not simply of its presence there, is of significance. This is the basic difference between the matrix so obtained and the presence-absence matrix, table Appx. 3.2.

It is a feature of the Robinson-Brainerd coefficient, when used in this way, that two cemeteries sharing a single type could be rated with a similarity of 200 (the maximum possible), if that were the only type present at each. Yet two other cemeteries, sharing several types in common, could be rated as less similar if they also possessed other types which were not common to both.

The laborious computations involved were accomplished by means of an IBM 7094 computer through the kindness of, and using the program by, Richard Kuzara, George Mead and Keith Dixon. This matrix, in the order resulting from computer seriation by means of the program of Kuzara, Mead and Dixon (1966) forms table Appx. 3.3. However, for reasons of economy, the seriation conducted did not use all the procedures which their program allows, and this ordered matrix may not be the best which their method could produce. Since the matrix has been sorted, the cemeteries are listed in what should, on the basis of the assumptions underlying the method, be their chronological order.

As part of its output, the computer also presents its own original percentile incidence matrix, with the cemeteries now arranged in the order resulting from the computer seriation. This presents for each type of object in each cemetery the percentage contribution which that type makes to the total grave goods found in the cemetery. Cemeteries similar to Chalandriani in Syros are at the lower part of the incidence matrix (table Appx. 3.4).

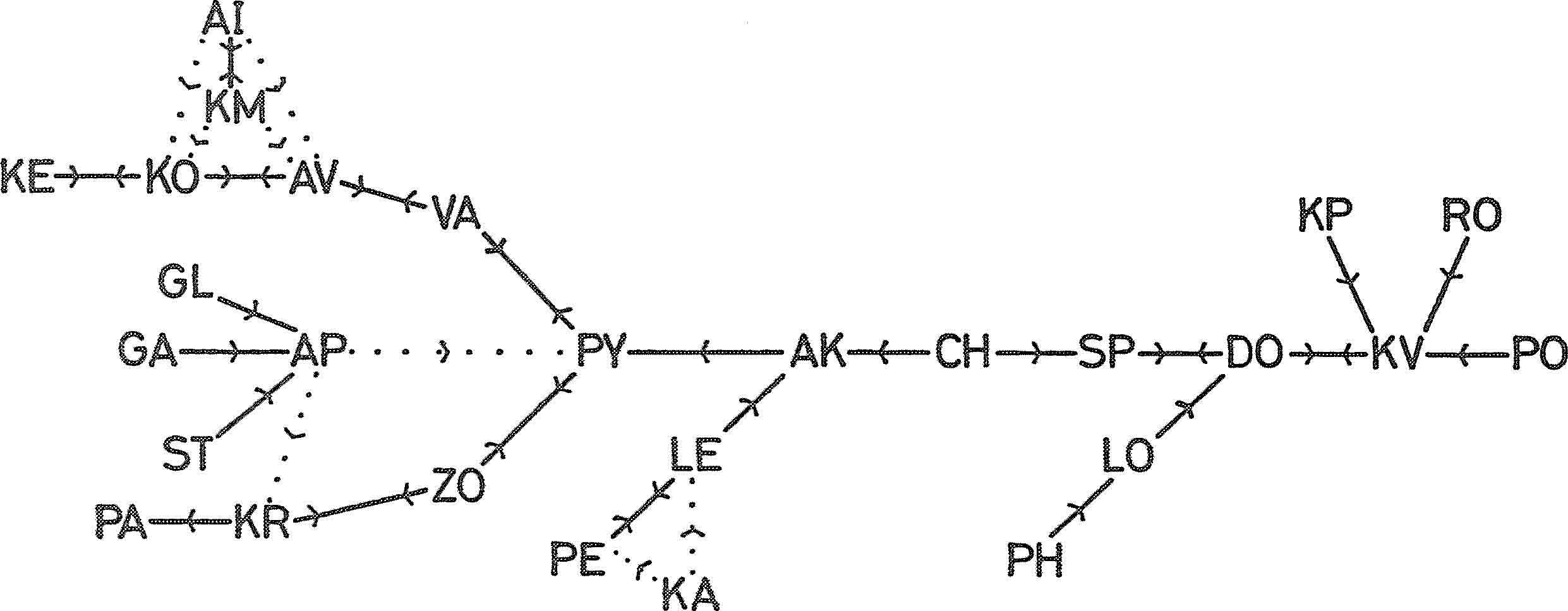

It is possible to apply the procedures of close-proximity analysis to a matrix such as table Appx. 3.3 just as to a matrix with presence-absence similarity coefficients. When this procedure is carried out, using the similarity coefficients calculated by computer from the cemetery percentages, the configuration is as shown in fig. 9.3.

FIG. 9.3 Close-proximity structure for the Early Cycladic cemeteries using similarity coefficients calculated by computer (table Appx 3.3). Two cemeteries with low coefficients have been omitted.

Here now we see the answer which close-proximity analysis gives to the data contained in matrix Appx. 3.3. And, of course, the actual order of cemeteries in matrix Appx. 3.3 is the computer’s own answer, after application of the Kuzura-Mead-Dixon seriation procedure. The close-proximity solution using the presence-absence similarity matrix was given in fig. 9.2.

It has thus been possible to apply three slightly different analytical procedures, each of which takes as its starting point the same data, namely the information contained in the incidence matrix, table Appx. 3.1. It is thus particularly satisfactory that the finds from Chalandriani, Kapsala, Karvounolakkoi, Spedos and Dokathismata are classed together by all three procedures. Polichni, Roön and Stavros are classed with these in some cases, and Roön and Stavros both show types relating closely to those of the others. And in all three procedures the key cemetery of Akrotiraki in Siphnos, which contains material resembling both that from Pelos and from Chalandriani, occupies an intermediate position.

It is here proposed that the cemetery finds be divided, upon this basis, into two groups whose status as cultures will be argued in the next section.

The first of these is the Grotta-Pelos culture (or Pelos-Lakkoudhes culture, as Doumas would prefer to term it). The finds resemble those from Panaghia in Paros, Zoumbaria in Dhespotikon, Pelos in Melos and indeed all those cemeteries to the left of Akrotiraki in the three orderings given. The special status of the Aghios Nikolaos and Louros cemeteries is discussed in Appendix 2. The following types, as numbered In the incidence matrix (see the list in Appendix 3) may be classed as belonging exclusively to the Grotta-Pelos culture: 1 to 8 inclusive, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17, 19.

The Keros-Syros culture has types such as are seen at cemeteries listed to the right of Chalandriani on the three orders given (with the exception of Louros, which is discussed in Appendix 2). The following types in the incidence matrix thus belong to the Keros-Syros culture, and are not found in the Grotta-Pelos culture: 22, 23, 25 to 27 inclusive, 30 to 39 inclusive, 41 to 50 inclusive, 53.

We may note also that obsidian (type 9), palettes (13), marble bowls of simple form (16), stone rubbers (21), shells (28) and colouring matter (29, 51) are found in graves of both cultures, as may also be certain generalised categories (20, 24, 40, 52). Schematic figurines of both cultures were classed as type 18, although in fact the forms are somewhat different in the two cultures.

TABLE 9.1 Grave goods from the cemetery of Akrotiraki on Siphnos.

The division of cemeteries into Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros is already clear enough. However, it should be noted that as well as Akrotiraki in Siphnos, four other cemeteries of those listed have finds both of the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros cultures (Apollona, Phyrroghes, Karvounolakkoi and Spedos; on the other hand type 34 has been shown in error as present at Krassades). In general, however, objects from the two cultural assemblages are not found in the same grave, or in the case of a double grave, accompanying the same burial.

This is well exemplified by a grave-by-grave consideration of the Akrotiraki cemetery. We see that the two graves contained goods of the Keros-Syros culture, and four had goods of the Grotta-Pelos culture. Indeed, of all the graves which have been studied from the cemeteries indicated, only in one single case do objects from the two different cultural assemblages occur together. This is Grave 38 B at Apollona in Naxos, where a marble-footed vessel (kandila) of type 14 was found together with a copper or bronze dagger of type 23 (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pl. 77–78). In so exceptional a case there may be some special explanation: perhaps the kandila, which is not in good condition, was an heirloom, already old when it was buried.

Further details of the analytical methods which have been used here will be found in a recent paper (Renfrew and Sterud 1969). The interpretation of the division of the cemetery material is discussed in the next section. For the present it is sufficient to conclude that the material does indeed divide very clearly into two distinct assemblages in this way. Most types can be ascribed specifically to one or other of the two cultures, and in consequence, when there are any grave goods at all, it is usually easy to decide to what culture the burial belongs.

Three groups of material of the Cycladic early bronze age have now been distinguished. It remains to investigate the chronological and geographic relationships between them.

The Phylakopi I culture is known, in the first instance, from both the settlement and the cemeteries at the type site in Melos. The second important settlement of the culture is at Paroikia in Paros. Finds of the same kind come from Siphnos, Amorgos and Naxos (figs. 12.2, 2; 12.1, 4; see fig. Appx. 1.2).

The Grotta-Pelos culture is known from cist-grave cemeteries throughout the central and southern Cyclades. As argued above, the settlement finds, with which the grave goods may be associated, come from the pre-city levels at Phylakopi, from Grotta in Naxos and from other sites in Amorgos, Siphnos and Melos. This may be regarded as a genuine archaeological culture, with a coherent distribution, and with finds from both settlements and cemeteries (see fig. Appx. 1.2).

The Keros-Syros culture is known again, in the first instance, from cemeteries in the northern and central Cyclades, with outlying finds (chiefly folded-arm figurines) from as far south as los and Thera. Several settlements are known, notably at Chalandriani in Syros, at Dhaskalio in Keros, on Mt Kynthos in Delos, and in Naxos. A number of unexcavated sites of this culture have yielded pithos handles with slashed incisions on the upper surface. The distribution of sites is again a coherent one. The Keros-Syros culture, like the other two, may be regarded as a well-defined culture of the Cycladic early bronze age.

The chronological relationship between the Grotta-Pelos and Phylakopi I cultures is easy to establish. Grotta-Pelos finds were found below Phylakopi I levels at Phylakopi itself. And in Paros, the one major site of the Phylakopi I culture at Paroikia may be regarded as the successor of the many smaller sites of the Grotta-Pelos culture, just as Phylakopi I succeeded the Grotta-Pelos sites in Melos. Moreover, at Phylakopi the Phylakopi I culture develops without interruption into the middle bronze age Phylakopi II culture. It seems altogether logical to regard the Phylakopi I culture as belonging to the later part of the early bronze age in the southern Cyclades, and the Grotta-Pelos culture as falling within the earlier part of the early bronze age in both the central and southern Cyclades.

Turning now to the Keros-Syros culture, we have four lines of approach in seeking to establish its position with respect to the other two cultures. First there is some very limited stratigraphic evidence. Then there is the information yielded by the analysis of the cemetery assemblages in the last section; and thirdly the distribution of sites shown on fig. Appx. 1.2. And finally there is the information which may be afforded by the comparison of Cycladic finds with those from other areas. But in order to avoid circular reasoning at a later stage, this fourth source of information will be discounted here. The stratigraphic information for the Keros-Syros culture is so far extremely limited, coming solely from Phylakopi. As stated above, pottery apparently of the Keros-Syros culture was found stratified there in levels between those of the Grotta-Pelos and Phylakopi I cultures. It is to be hoped that further excavations in Naxos—where finds of both the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros cultures are most common—will give a clearer stratigraphic documentation.

The distribution of the two cultures is interesting. There are no finds of the Grotta-Pelos culture in the northern Cyclades (e.g. Syros and Mykonos), while Keros-Syros finds scarcely occur on Paros or Antiparos (although there are a few from Dhespotikon). Finds of both cultures are common on Naxos. Thus, although the distributions are not identical, they are not complementary. In particular, the Keros-Syros culture finds in south-east Naxos, in Keros and in Amorgos discourage any attempt to claim the Keros-Syros culture as ‘north’ and the Grotta-Pelos culture as ‘south’, in the manner of some scholars. It should be noted too that a jar with stamped decoration resembling somewhat the footed jars of Syros, has been found at Phiropotamos in Melos (pl. 8, 9).

Indeed the detailed analysis in the last section rules out any attempt at a solely geographical division. If the locations of the cemeteries in fig. 9.3 are considered, and the names of the cemeteries replaced by those of the islands on which they are located, the diagram, fig. 9.4, is obtained (N indicates Naxos; P, Paros; D, Dhespotikon; O, Antiparos (Oliaros); A, Amorgos; S, Siphnos; Sy, Syros; M, Melos).

No coherent pattern emerges from this exercise, and it is clear that the differences between the cemeteries cannot be explained solely or even principally by a geographical factor. On the contrary, while the Paros cemeteries lie on the left side of the diagram, and the Amorgos ones to the right (suggesting perhaps some east-west variation), Siphnos, which lies between these on the diagram is geographically far to the west of Paros. And of course the Naxos cemeteries are widespread throughout the diagram. There is little systematic geographical clustering.

An obvious alternative hypothesis is that the variation is largely a chronological one. On this view the Keros-Syros culture would not be the contemporary of the Grotta-Pelos culture, but largely later (or, alternatively earlier) in date. The limited stratigraphic evidence from Phylakopi, and the frequency of metal finds in Keros-Syros contexts document that if the two cultures are in succession, the Keros-Syros culture will be the later of the two.

The distinction between the two cultures must surely have a chronological significance, for otherwise it is difficult to see how such a rigid separation could occur as in the cemetery at Akrotiraki, where graves 145 and 147 are of the Pelos group and 142 and 143 of the Syros group. A similar situation is seen at the cemeteries of Karvounolakkoi and Phyrroghes in Naxos. The notion of a Grotta-Pelos people and a Keros-Syros people living together in the same settlement and yet retaining a rigid difference in cultural forms and in grave goods, seems difficult to accept. Far more plausible is the replacement of the Grotta-Pelos customs in the settlement by those of Keros-Syros, conceivably with some change in the population, but without a total break in continuity.

FIG. 9.4 A test to determine whether the close-proximity structure for the Early Cycladic cemeteries (fig. 9.2) is determined by their geographical distribution. In each case the name ofthe island where the cemetery occurs has been substituted for the name of the cemetery itself. No coherent pattern emerges: the structure is not based on distribution, but reflects cultural (and perhaps chronological) factors.

The rather scanty stratigraphical evidence provided by Phylakopi on this point is thus supported by the pattern of associations in the cemeteries. However, the evidence derived from comparisons with other Aegean cultures is in some ways weightier. The close ties of the Keros-Syros culture with the Korakou culture of the mainland, with Troy II–V and with Early Minoan II will be illustrated in chapter 13. They depend largely on the Urfirnis ‘sauceboats’ and one-handled jugs, and the folded-arm figurine. The Grotta-Pelos culture has links, on the other hand, with the final neolithic of the mainland as well as the Eutresis culture, with Kum Tepe lb in the Troad, and with Early Minoan I in Crete, as will be seen in chapter 13. These synchronisms do not rule out the survival of the Protocycladic cultures into the middle bronze age, as is demonstrated by the Amorgos daggers and by the find of imitation Middle Minoan cups in a cist grave at Aïla in Naxos (Papathanasopoulos 1962, pl. 63).

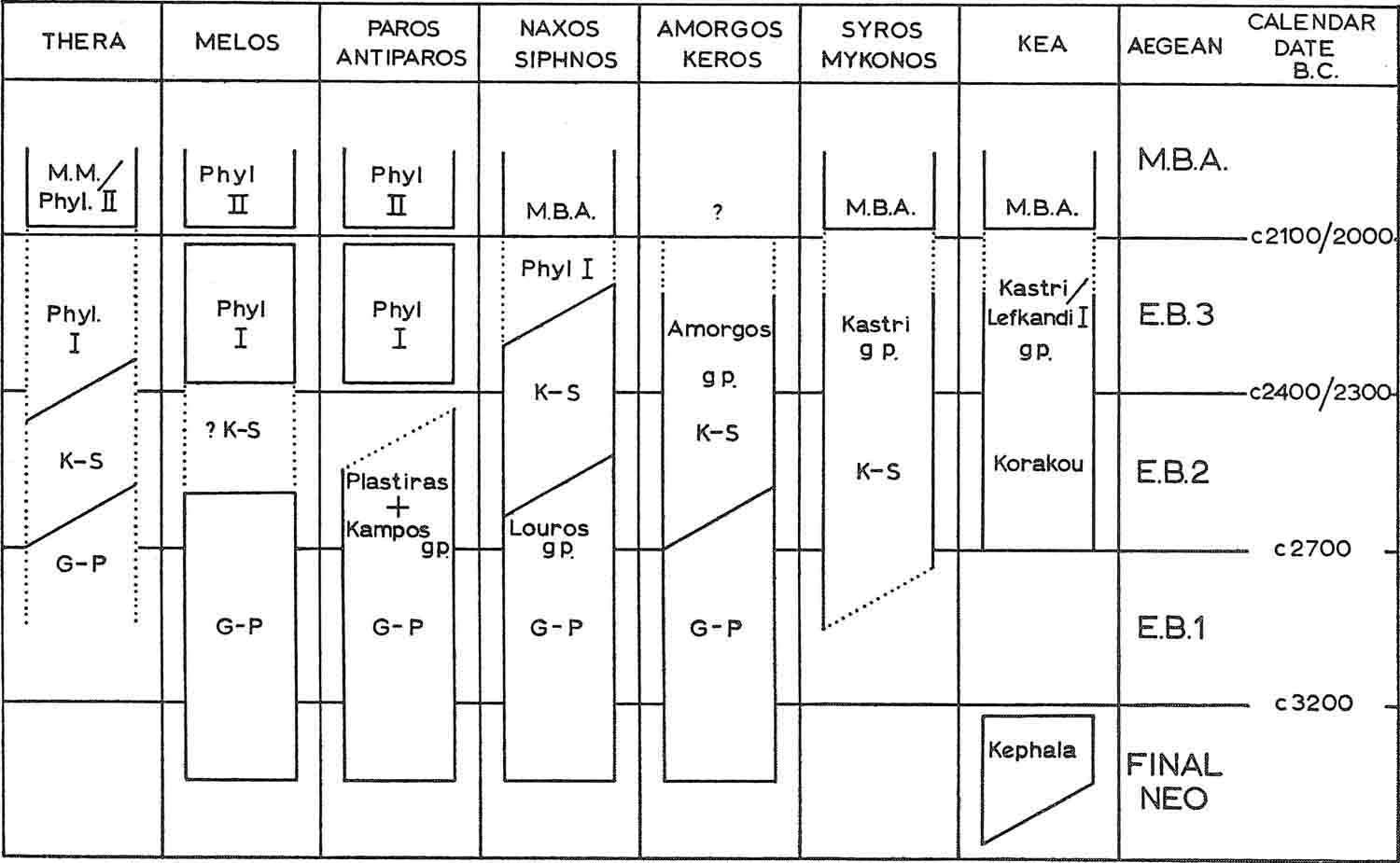

It is noticeable that the rigorous division in material is not followed by the grave forms. The built graves of Syros are found again only at Lionas in north-east Naxos and apparently at Dhiakophtis in Mykonos. Objects of the Keros-Syros culture are often found in cist graves. Sometimes in Siphnos and Naxos, as described, they are found in the same cemeteries as the earlier Pelos material (but generally not in the same graves). This suggests that where the Keros-Syros culture followed upon the Grotta-Pelos, the transformation was a peaceable one with continuity in settlement and in burial practice, so that although new grave goods came into fashion, the traditional tomb construction was retained. It is thus probable that the early phases of the Keros-Syros culture, doubtless in Syros, were contemporary with the developed Grotta-Pelos culture. And it is clear too that the later Keros-Syros culture, in Amorgos at least, must have overlapped in time with the Phylakopi I culture (cf. chapter 11). It is not indeed impossible that the Phylakopi I culture followed directly on a very late stage of the Grotta-Pelos culture in Melos and Paros, since Keros-Syros finds are so scarce on those islands, although a complete cultural break is also quite conceivable. In Syros, Siphnos and Keros and apparently Naxos, the Phylakopi I culture is scarcely seen, so that the Protocycladic cultures may have lasted there until the middle bronze age. These chronological relations are schematically represented in table 9.2. It has been compiled using the information given in the Gazetteer’, Appendix 1. Further research may eventually fill some of the apparent lacunae. The basic cultural divisions are further discussed in the next three chapters.

TABLE 9.2 The early prehistoric culture sequence in the Cycladic islands. G-P indicates Grotta-Pelos culture; K-S, Keros-Syros culture; PhyI. I, Phylakopi I culture.

Broadly speaking, however, the sequence Grotta-Pelos, Keros-Syros, Phylakopi I seems supported by the Phylakopi stratigraphy, the cemetery associations and the Aegean parallels. These cultures will be discussed in turn in the three succeeding chapters.