Phylakopi is the only place in the Cyclades where large areas of a settlement dating from the early bronze age have been cleared. In the light of Mackenzie’s Daybooks there can be no doubt that extensive remains of the First City (‘Phylakopi I’) were stratified below the Second City (‘Phylakopi II’). The Second City was a fortified town of middle bronze age date, as is clearly shown by the imports of Kamares and Minyan ware and the export of its characteristic curvilinear style pottery to MM Ib Knossos, Lerna V and elsewhere.

The architectural remains (Atkinson in Atkinson et al, 1904, 35 f.) are of a rather similar nature to those of the Second City (ibid. pl. 1). Phylakopi is indeed the only Early Cycladic site which can reasonably claim to be regarded as a town. The area of settlement was similar to that of the better preserved Second and Third towns (fig. 12.3), with a length of about 180 m. There was apparently no fortification wall at this time, but the plan of one house suggests that already the houses were packed together in compact blocks, divided by narrow streets as In the second settlement, and indeed in much the same way as a modern Cycladic village of traditional form such as Kastri on Siphnos. The straight walls, right-angle corners, and consistency of orientation contrast markedly with the informal plan of Keros-Syros settlements such as Kynthos or Kastri on Syros. It seems likely indeed that there was some planning in the town layout, and that Phylakopi, as well as being the largest of the Early Cycladic settlements, was the most rationally organised.

The wall at this site is of Phylakopi II date (pl. 21, 3). Indeed while the defences of Chalandriani (pl. 21, 1) and Panormos (pl. 21, 2) with their round bastions are certainly Early Cycladic, walls with larger squared stones and sometimes rectangular towers are a middle bronze age feature in the Cyclades. This is true both for Phylakopi and Akroterion Ourion in Tenos. The great defences at Aghios Andreas in Siphnos have never been adequately dated, and may be much later.

The fortifications at Aegina likewise (fig. 18.11, 4) may well be of middle bronze age date, for although dated by Welter to the Early Helladic period, no stratigraphical evidence has been produced for this or indeed any of his ill-recorded excavations.

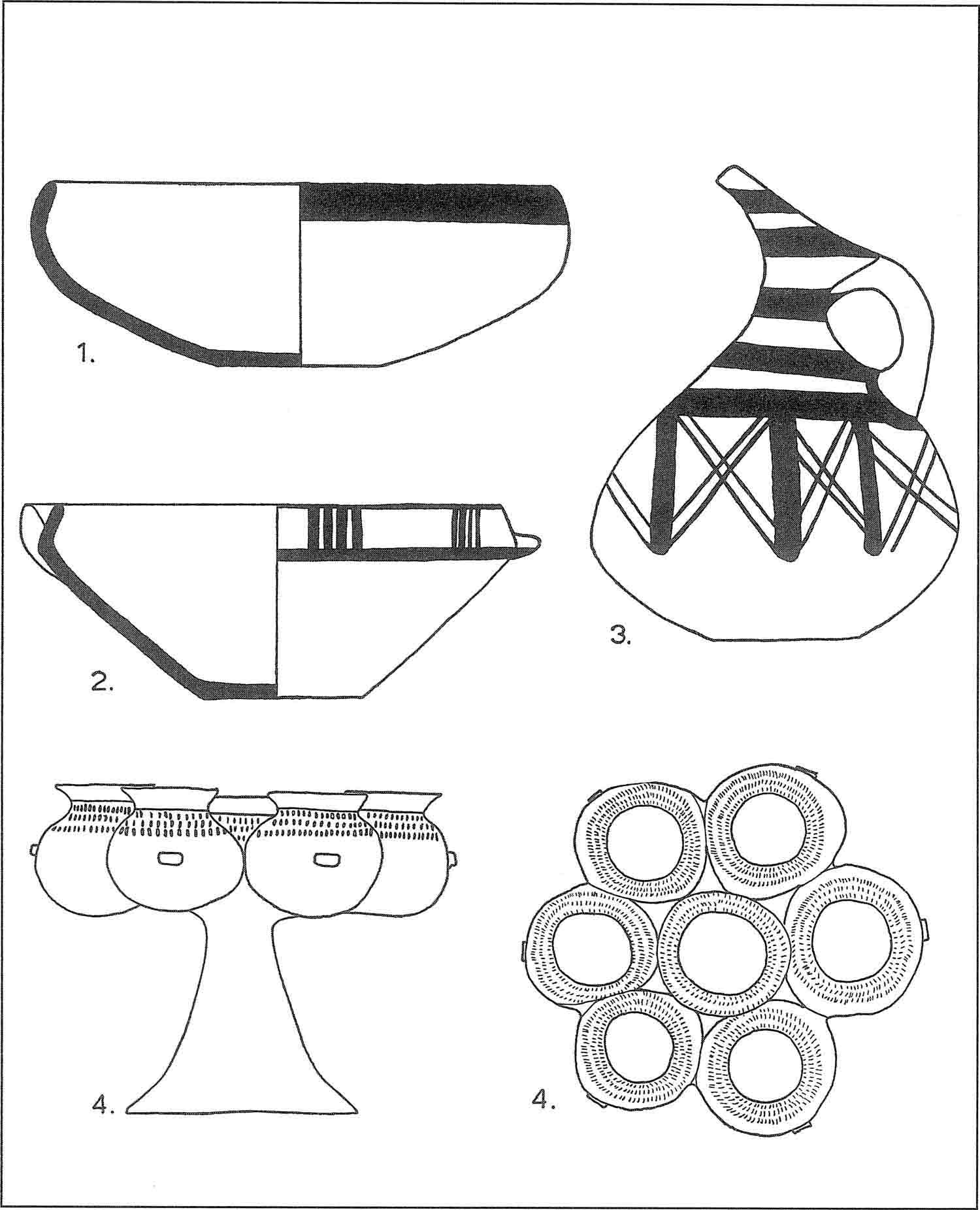

FIG. 12.1 Forms of the Phylakopi I culture, nos. 1 to 3 with dark-on-light painted decoration. Scale 2:5.

FIG. 12.2 Incised pottery forms of the Phylakopi I culture. Scale 2:5.

Numerous closed finds of pottery were recorded by Mackenzie and this allows us to reconstruct the typical ceramic assemblage of Phylakopi I. In the incised wares the most prominent shapes were the conical pyxis (fig. 12.2, 1) with a variety of lids (fig. 12.2, 3 and 4; pl. 10, 5), and the duck vase (fig. 12.2, 5 and pl. 12) which could be decorated in several schemes. A selection of incised sherds from Phylakopi, now in the National Museum in Athens, is shown in pl. 10. Other less common incised forms are seen in the Phylakopi publication (Atkinson et al. 1904, pl. IV, notably 7 and 9). At this time too were many undecorated vases with a dark and lustrous appearance produced by the application of a special slip, followed by burnishing. Their production continued well into the middle bronze age, for imitations of Minyan ware are found in this fabric (Edgar in Atkinson et al. 1904,153). Sometimes this ware resembles the products of the Keros-Syros culture so closely that, on the grounds of fabric alone, it is exceedingly difficult to make a distinction, and there are some vessels in the National Museum whose date remains uncertain. The line between Urfirnis—supposedly an unburnished slip of glazed appearance—and a burnished slip seems a very hazy one.

A similar difficulty is often experienced with the lustrous painted wares and the matt ones. The paint of the Keros-Syros culture often retains some lustre, and that of the curvilinear style of middle bronze age Phylakopi II is certainly matt and chalky, but between the two is often a situation of some doubt. Edgar makes a firm distinction in the pottery with geometric designs between that with lustrous paint and that with matt (ibid., 96 and 102), and indeed when newly excavated and wet after washing the pots may have shown this lustre more clearly. It is very difficult to detect today however, and Mackenzie generally regarded all the early ‘geometric’ (i.e. rectilinear) decoration as a lustreless one, contrasting it with the painted wares of the late bronze age. It seems safest to judge today by shape and decoration rather than technique.

The most frequent shape among the painted wares is the Melian pouring bowl (fig. 12.1, 2) which often does not have a spout (fig. 12.1, 1). The beaked jug (fig. 12.1, 3; pl. 10, 2) is common as are the pithos (pl. 10, 1) and the one-handled cup. A striking find occasionally appearing in the settlement, and more often in the cemeteries, is the kernos (pl. 11, 1; Forsdyke 1925, 63, fig. 75). A single unpainted example is also known from Naxos (fig. 12.1, 4). Obsidian was still much used at this time, but there was disappointingly little metal found at Phylakopi, nor were figurines very common.

The extensive cemeteries of rock-cut tombs (fig. 7.6, 3–6), which are the only known graves of the culture, were not well dated in the publication. But surface collection at the Hill Cemetery and especially at the West Cemetery has produced Phylakopi I sherds including kernos and duck vase fragments and sherds painted in the ‘geometric’ style, as well as later wares. It can thus reliably be stated that the use of these tombs began during the Phylakopi I period and continued through much of the middle bronze age and perhaps beyond.

The other excavated site of the Phylakopi I culture is Paroikia in Paros (Rubensohn 1917), situated likewise on a low hill overlooking the sea. The Phylakopi I pottery there is well illustrated in Rubensohns excellent report. Examples of the incised ware from Paroikia are seen in fig. 12.2, 1 and 5. Of interest is a painted duck vase (ibid., fig. 57) and the large quantity of light-on-dark painted ware (ibid., 45). This is a fabric also seen at Phylakopi. Edgar believed it to be a rather later technique than the dark-on-light, and its use extended into the middle bronze age. In some cases it clearly imitated the incised motifs of Phylakopi I, but its introduction could be due to imitation of the 'Early Minoan III white-painted ware of east Crete, if that is really earlier than the Middle Minoan period. Closer similarities are seen in some Middle Helladic pottery (Frödin and Persson 1938, 275 and fig. 191) which may well be indebted to inspiration from the Cyclades. As is generally the case with Phylakopi I sites, occupation at Paroikia continued apparently unbroken into the middle bronze age.

FIG. 12.3 Plan of the Third City at Phylakopi. The preserved remains of the First (early bronze age) City suggest that it was similar in size and general lay-out to the Third (late bronze age) City, although lacking the later fortification wall and the megaron ‘palace’. The squares are of side 20 m (after Atkinson).

Traces of Phylakopi I occupation are scanty in Siphnos and Naxos; there are duck vase sherds and an incised conical pyxis (fig. 12.2, 2) in the Apeiranthos Museum. In Syros the only example known is a poor incised conical pyxis of late date (Tsountas 1899, pl. 9, 24). At Aghia Irini in Kea the affinities are chiefly with the mainland and the Kastri group. Nothing of the culture has been published from Mykonos or Antiparos, indeed the distribution seems to be largely a southern one (fig. Appx. 1.2), for there are finds both in Amorgos and Thera (pl. 12, 1, 2 and 6).

The Phylakopi I culture is certainly later in date than much of the Keros-Syros culture, as was seen in chapter 9, although duck vases have been found in cist graves of the rather late Amorgos group. This view is confirmed by the various parallels for the pottery in the Aegean area.

Despite the southern distribution of the culture there is no good evidence for contacts with Crete, which are so firmly established in the succeeding Phylakopi II culture. The pyxis and incised sherds from the Vat Room Deposit at Knossos which have been hailed as Cycladic imports and used to supplement the scanty evidence for the Early Minoan III period (Evans 1921–35, I, 166), are surely Early Minoan I in shape, and if incised decoration is taken to be a Cycladic feature—which hardly seems necessary in Crete—it is common enough in the earlier Grotta-Pelos culture.

It is surprising perhaps that no duck vases have been found in Crete. This form, which must be distinguished from the askos of the Korakou culture, is common enough on the mainland and in Anatolia (fig. 12.4). Fragments were found at Troy IV (Blegen et al. 1950, II, 110), and perhaps at Early Bronze 3 Beycesultan (Lloyd and Mellaart 1962, fig. P3.1). Characteristic sherds from Kalimnos were rightly separated by Furness (1956, fig. 11) from the earlier material there, a particularly fine example comes from Bozhüyük (pl. 12, 4), and several were found at the Heraion in Samos. There it is limited to Period IV (Milojčić, 1961, 65) which is equivalent to Anatolian Early Bronze 3, (Lloyd and Mellaart 1962, 231). At the Heraion such Troy II forms as the depas cup (Milojčić 1961, p. 28, 7) occur only in Period III. On these grounds therefore the Phylakopi I culture can be equated with Anatolian Early Bronze 3, and it appears in Anatolia later than the various Keros-Syros forms, although these do in fact persist well into the Early Bronze 3 period at Troy and elsewhere.

Contacts on the mainland are still more numerous: duck vases occur in the Athenian Agora and are numerous at Aegina (pl. 12, 3 and 5); one indeed with its curious incised decoration recalls the little prototype from the Kastri at Syros (fig. 11.2, 1). Painted beaked jugs are found there too as well as pithoi. Incised wares at Aegina (pl. 10, 6) and Athens compare closely with the Phylakopi I style. Other rather similar fragments come from phases IV to I at Emborio in Chios, where they seem related in turn with the incised wares of Troy I and especially of the Yortan culture (Forsdyke 1925, fig. 15). But there is not enough evidence at present for very definite conclusions to be drawn from the Anatolian similarity.

Unfortunately the stratigraphical position of the Aegina finds is not recorded, and we have no proof that they are contemporary with the painted wares of the Tiryns culture found there, as one would suppose. Indeed although there are parallels for Phylakopi I in mainland contexts at the end of the early bronze age (e.g. an incised handle: Goldman 1931, fig. 168), the closest comparisons are to be found in the Middle Helladic period. Not only is the duck vase found (ibid., fig. 255) but there is also at Eutresis a four-footed vessel of distinctive shape (ibid., pl. XII and fig. 257) which is just like those found at Phylakopi (Atkinson et al. 1904, pl. IV, 7). We are thus led to set the Phylakopi I culture as contemporary with the end of the early bronze age and the beginning of the Middle Helladic period on the mainland. The difficulty here, however, is that it must be prior to Middle Minoan lb and probably even to Middle Minoan la, since pottery of that style is found in the Second City. Such fine chronological matters can only be resolved by re-excavation at Phylakopi and the division there of both the First and Second City periods into sub-phases. Until this is undertaken we must regard Phylakopi I as an early bronze age culture with affinities on the mainland that last into the middle bronze age.

FIG. 12.4 Findspots of duck vases in the Aegean.

1, Phylakopi; 2, Paroikia; 3, Naxos, uncertain location; 4, Dhaskalio; 5, Amorgos, uncertain location; 6, Thera; 7, Eutresis; 8, Athens Agora; 9, Brauron; 10, Aegina; 11, Lerna; 12, Vathy; 13, Izmir; 14, Beycesultan; 15, Heraion. Not indicated: Troy.

So wide a range of new pottery forms in the First City might seem to suggest the operation of influences from the outside. Yet in fact all the essential aspects of the Phylakopi I culture can be traced back to the earlier cultures of the Cycladic early bronze age, although the excavation of another such deposit as that of square J1 at Phylakopi would be required to establish this in detail.

The suggested presence of Keros-Syros sherds in the twelfth half-metre there (ibid., 86) is of some importance for the development of the culture. For dark-on-light painting could be derived from these (and at Phylakopi this was supposedly a lustrous technique at the outset), as also the rather glutinous slip seen on some Phylakopi I wares. The rectilinear designs on some Phylakopi I pottery may equally show Keros-Syros inspiration, and the beaked vase, although of a different shape at Phylakopi with an S-shaped profile and no separate neck, is clearly related to those of Early Bronze 2. The find of a proto-duck-vase at Kastri (fig. 11.2, 1) has already been noted and several duck vase spouts were found at the Keros-Syros site of Dhaskalio. The Kastri finds include also jugs with long vertical necks which might well constitute a prototype for the striking jug form at Phylakopi I. In addition, some of the Phylakopi I incised pottery is decorated with stamped concentric circles (pl. 10, 4; Atkinson et al. 1904, pl. V, 16), which is a prominent feature in Syros. The finds of folded-arm figurines at Phylakopi confirm this general impression of Keros-Syros influence, especially at the time of the Kastri group.

But the Grotta-Pelos culture must have had its impact too. In particular the pyxis form, although conical in Phylakopi I and cylindrical earlier, is a link, as Is the taste for incised decoration. Rather close influences indeed can be found on some of the incised or painted pyxis lids of Phylakopi I, although their shape is slightly different.

The one-handled cup and the pithos can both be derived from earlier Cycladic forms, and the Melian bowl is in profile identical with those of the Troy I period (compare fig. 12.1, 1 with fig. 5.3, 11). Indeed amongst the Kum Tepe Ic examples are many with a lustrous slip which are indistinguishable from Phylakopi I finds. Even the kernos has respectable antecedents in the area: a simpler version was found in an early grave in the West Cemetery (pl. 11, 2) and this may be compared with one from Naxos (fig. 12.1, 4) and an example from Koumasa in Crete (pl. 11, 3). In this way all the principal ceramic forms of the Phylakopi I culture may plausibly be explained without looking very far afield.

The rock-cut tomb (fig. 7.6, 3–6) is, however, a new feature for the Cyclades, and indeed this form, with no shaft but a straightforward portal entrance, is a new one in the Aegean, although frequent enough in the west Mediterranean at about this time. But of course there are rock-cut tombs in Euboia (fig. 7.6, 1–2) of comparable date, and very similar tombs from the same period have been found in Corinth (Heermance and Lord 1897). The earliest known from the mainland however is a shaft tomb of very similar type in the Athenian Agora (fig. 7.6, 8; Shear 1936) which contained pottery to be dated to the end of the neolithic period. The tombs of Phylakopi thus have respectable antecedents in the west Aegean. Once again therefore we are faced in Attica or the Cyclades with an earlier practice of burial customs than is seen in Anatolia, where they are often considered to have originated.

The Phylakopi I culture, together probably with the Kastri and Amorgos groups—the tail end of the Keros-Syros culture—brings the Cycladic early bronze age to a close. Although a delightful and individual ceramic tradition persists, the independence of the Cyclades is at an end, and for the remainder of the prehistoric period the islands fall within the cultural sphere of Crete or of the mainland.