Regrettably, Part I falls short of providing a complete new paradigm and theoretical framework for analyzing the relations between human economic activity and the natural environment. Hopefully, it will sensitize us to pitfalls in traditional economic thinking and provide useful clues about new thinking we must engage in. In any case, we are now ready to apply our new mind-set to analyzing why the economic system tends to place the environment at risk.

When properly understood, a number of mainstream concepts and theories can help us understand why in private enterprise market economies we overpollute, overexploit, and underprotect the natural environment. Understanding the nature of what economists call “perverse incentives” created by externalities, public goods, free access to common property resources, and resource extraction under private ownership can take us a long way toward understanding the sources of environmental problems. Since mainstream economists invariably defend the private enterprise market system, environmentalists who sense that our major economic institutions are largely responsible for environmental distress assume there is little in mainstream economic theory that sheds light on where problems arise. Surprisingly, this is not the case. The problem is that the mainstream literature on perverse incentives is underadvertised by a profession dedicated to providing ideological support for the dominant economic system of our age, and these perverse incentives are rarely interpreted as reason for concern.

Mainstream economic theory teaches that the problem with externalities is that the buyer and seller have no incentive to take the external cost or benefit for others into account when deciding how much of something to supply or demand. And mainstream theory teaches that the problem with public goods is that nobody can be excluded from benefiting from a public good once anyone buys it, and therefore everyone has an incentive to “ride for free” on the purchases of others rather than revealing a true willingness to pay for public goods by purchasing them in the marketplace. In other words, mainstream economics concedes that the laws of the marketplace will lead to inefficient allocations of productive resources when public goods and externalities come into play because important benefits or costs go unaccounted for in the market decision-making procedure. If anyone cares to listen, standard economic theory predicts that market forces will tend to produce too much of goods whose production and/or consumption entail negative externalities, too little of goods whose production and/or consumption entail positive externalities, and much too little, if any, of public goods. We illustrate the problem of negative externalities by looking at the automobile industry, and the problem of public goods by considering pollution reduction.

A great deal of mainstream economic theory is devoted to explaining why markets can be relied on to allocate scarce productive resources efficiently. Of course, this vision has been with us since the time of Adam Smith ([1776] 1999), who popularized the idea of a beneficent “invisible hand” at work in capitalist economies over 200 years ago in his Wealth of Nations. How does the beneficent invisible hand work, and when do beneficent invisible hands turn into malevolent invisible feet?

Smith reasoned that sellers would keep supplying more of a good as long as the price they received covered the additional costs of producing them. In other words, Smith assumed that market supply curves would be the same as suppliers’ marginal cost curves. He also reasoned that buyers would keep demanding more of a good as long as the satisfaction they got from an additional unit was greater than the price they had to pay for it, in which case market demand curves would be the same as buyers’ marginal benefit curves. But if market price keeps adjusting until the quantity suppliers want to sell is the same as the quantity buyers want to buy, this means that every unit that benefits buyers more than it costs producers to make will get produced, and no units that would cost more to produce than the benefits buyers would enjoy from them will be produced. Therefore, according to Smith, every unit we should want to be produced will be, while none we should not want produced will be produced—that is, the market will lead us, as if guided by a beneficent invisible hand, to produce exactly the socially optimal, or efficient, amount of the good.

What can go wrong? In his defense, as discussed in Chapter 1, nobody in Smith’s day distinguished between private costs to sellers and costs to society as a whole, or between private benefits to buyers and benefits to society as a whole. It fell to A.C. Pigou ([1912] 2009) to raise these disturbing possibilities over 100 years later when it was more apparent that the world was no longer empty. If there are what Professor Pigou first called external costs associated with producing something—that is, costs borne not by the seller but by someone else—then the marginal social cost (MSC) of producing something will be greater than the marginal private cost (MPC). And if parties other than the buyer of a good are affected when it is consumed, either positively or negatively—that is, if there are what Professor Pigou first called external effects when a buyer consumes a good—then the marginal social benefit (MSB) that comes from consuming the good is different from the marginal private benefit (MPB) to the buyer alone. Problems arise because neither sellers nor buyers have any incentive to take consequences for third parties into account, which means that the market decision-making process, in which only buyers and sellers participate, will fail to take external effects into account. If the external effects are negative consequences for “third” parties, the market will end up leading us to produce and consume more of the good than is socially efficient by effectively disenfranchising parties other than the buyer and seller who are negatively affected. If the effects on external parties are positive, the market will lead us to produce and consume less of the good than is socially efficient by excluding third parties who are positively affected from the decision-making process.

Today professional economists all agree that Adam Smith’s vision of the market as a mechanism that successfully harnesses individual desires to the social purpose of using scarce productive resources efficiently hinges on the assumption that external effects are absent, or insignificant. The assumption of no external effects is explicit in theorems about market efficiency in graduate texts, although usually implicit when most mainstream economists conclude that markets are remarkable efficiency machines that require little social effort on our part. However, driven in large part by research into environmental externalities over the past forty years, more economists are challenging this assumption, and a growing number of skeptics outside the mainstream now dare to suggest that externalities are prevalent and often substantial. Or, as Hunt and D’Arge put it, externalities are the rule rather than the exception, and therefore markets often work as if they were guided by a “malevolent invisible foot” that keeps kicking us to produce more of some things and less of others than is socially efficient.1

First, critics point to the absence of empirical evidence supporting the claim of external effect exceptionality. It is truly remarkable that this crucial assumption has never been subjected to serious scrutiny. Economists are well known for engaging in exhaustive empirical debates over assumptions that are far less important. But in this case, perhaps the most critical assumption about market economies—the assumption that externalities are small and rare—has not given rise to serious empirical debate and remains unsubstantiated by empirical studies. Instead it remains untested—an assumption of ideological convenience.

Lacking conclusive empirical studies, are there theoretical reasons to believe that externalities should be exceptional rather than prevalent? Obviously, increasing the value of goods and services produced, and decreasing the unpleasantness of what we have to do to get them, are two ways producers can increase their profits in a market economy. By increasing the value of goods produced, sellers can reasonably hope to sell more and/or sell at a higher price. By making work less onerous or by reducing labor or nonlabor inputs, producers can hope to lower labor or nonlabor costs. And competitive pressures will drive producers to do both, as Adam Smith argued long ago. But maneuvering to appropriate a greater share of the value of goods and services produced by externalizing costs and internalizing benefits without compensation are also ways to increase profits. And presumably competitive pressures will drive producers to pursue this route to greater profitability just as assiduously. Of course, the problem is that while the first kind of behavior serves the social interest as well as the private interests of producers, the second kind of behavior serves private interests at the expense of the social interest. When buyers or sellers promote their private interests by externalizing costs onto those not party to the market exchange, or internalizing benefits from third parties without compensation, their behavior introduces inefficiencies that lead to a misallocation of productive resources.

Market admirers seldom ask: Where are firms most likely to find the easiest opportunities to expand their profits? How easy is it usually to increase the size or quality of the economic pie we bake, so to speak? How easy is it to reduce the time or discomfort it takes to bake it? Alternatively, how easy is it to enlarge one’s slice of the pie by externalizing a cost or by appropriating a benefit without payment? Why should we assume that it is always easier to expand profits by socially productive behavior than by redistributive behavior that leads to inefficient uses of scarce resources and energies and is therefore socially counterproductive? The implicit assumption that it is always easier to increase profits through productive behavior than redistributive maneuvering is what lies behind the view of markets as efficiency machines.

Market enthusiasts fail to notice that the same feature of market exchanges primarily responsible for the small transaction costs so widely admired—excluding all affected parties but two from the transaction—is also a major source of potential gain for the buyer and seller. When the buyer and seller of an automobile strike their convenient deal, the size of the benefit they have to divide between them is greatly enlarged by externalizing the costs of air pollution from auto plants, and the costs of urban smog, noise pollution, traffic congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions caused by car consumption. Those who pay these costs, thereby enlarging carmaker profits and car consumer benefits, are easy “marks” for car sellers and buyers because they are geographically and chronologically dispersed and because the magnitude of the effect on each of them is small yet not equal. Individually, they have little incentive to insist on being party to the transaction. Collectively, they face transaction cost and free-rider obstacles to forming a voluntary coalition to represent a large number of people, each with little, but different amounts at stake.

Moreover, the opportunity for this kind of cost-shifting behavior on the part of buyers and sellers in market economies is not eliminated by making markets more competitive or entry costless, as is commonly assumed. Even if there were countless perfectly informed sellers and buyers in every market, even if the appearance of the slightest differences in average profit rates in different industries induced instantaneous self-correcting entries and exits of firms, even if every market participant were equally powerful and therefore equally powerless—in other words, even if we embrace the full fantasy of market enthusiasts—as long as there are numerous external parties with small but unequal interests in market transactions, those external parties will face greater transaction costs and free-rider obstacles to a full and effective representation of their collective interest than that faced by the buyer and seller in the exchange. It is this unavoidable disadvantage that makes external parties easy prey to cost-shifting behavior on the part of buyers and sellers.

Even if we could organize a market economy so that buyers and sellers never faced a more or less powerful opponent in a market exchange, this would not change the fact that each of us has smaller interests at stake in many transactions where we are neither the buyer nor the seller. Yet there is every reason to believe that the sum total interest of all external parties can be considerable compared to the interests of the buyer and the seller. It is the transaction cost and free-rider problems that put those with lesser individual interests at a disadvantage compared to buyers and sellers in market exchanges, in turn giving rise to the opportunity for individually profitable but socially counterproductive cost-shifting behavior on the part of buyers and sellers. So not only is there no empirical evidence that external effects are, truly, small and exceptional, there are strong theoretical reasons for expecting just the opposite to be the case. There is every reason to expect that competition for profit will drive buyers and sellers to seek out ways to externalize costs onto large numbers of disempowered third parties who are relatively easy marks, creating significant allocative inefficiencies in the process.

But what does all this have to do with pollution? For economists, pollution is a “negative externality” of production or consumption activity. Since market economies overproduce goods and services whose production or consumption entails negative external effects, as explained above, this means that while it may be efficient to pollute to some extent—when the benefits from the goods or services produced along with the pollution exceed the costs of producing them including the damage from the pollution—markets will predictably lead us to pollute beyond this point.

Since there are external costs associated with producing cars, the MSC of producing an automobile is higher than the MPC of producing the automobile, as shown in Figure 4.1. Since there are negative externalities associated with consuming cars, the MSB, of consuming a car is less than the MPB to the car buyer, as shown in Figure 4.1. As we know, the socially efficient number of automobiles to produce and consume is A(0), where MSC = MSB. However, market supply, S, depends on private costs, not social costs, and is therefore equal to MPC, not MSC, and market demand, D, depends on private benefits to buyers, not social benefits, and is therefore equal to MPB, not MSB. So when the laws of supply and demand drive the auto market to its equilibrium, they drive us to produce where S = D, or A(M). As Figure 4.1 demonstrates, since A(M) > A(0), when automobile producers and buyers predictably ignore the negative external effects of sulfur dioxide emissions from plants producing cars, and the negative effects of driving cars on local air quality, congestion, and greenhouse gas accumulations, we predictably produce and consume too many cars. By doing so, we also produce too much local air pollution, congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Although the magnitude of the external effects and consequent inefficiencies is particularly great, the automobile industry is hardly an exception. Besides producing cement, cement factories emit particulates that cause urban air pollution. Besides producing electricity, utility companies emit sulfur dioxide that causes acid rain. Besides producing fruits and vegetables, modern agriculture produces pesticide runoff that contaminates groundwater and rivers. Retail stores generate packaging that ends up in solid waste dumps at best and as litter at worst. The biosphere provides resources, assimilates wastes, provides amenities, and performs life support services. Whenever production or consumption diminishes the usefulness of the environment in any of these regards, it is likely to go unaccounted for in a market system since most of those affected will be third parties whose interests will not be considered by the buyer or seller in a market transaction. Expecting a free market system not to pollute too much is like waiting for a lead balloon to float.

But surely environmentally conscious people take the environmental effects of their actions into account. Is not the answer more environmental education so we all become “green” consumers, thus forcing producers to behave in environmentally responsible ways as well? We should consume so as not to pollute, and the environment certainly is better off because many who have become aware of the environmental consequences of their choices take those effects into account. But it is important to realize that a market system provides no incentives for people to engage in green consumerism. Quite the opposite, markets provide powerful incentives for consumers not to behave in environmentally responsible ways. To understand this, we need to consider a second major reason why market economies destroy the environment.

A public good is a good produced by human economic activity that is consumed, to all intents and purposes, by everyone rather than by an individual consumer. Unlike a private good, such as underwear, which affects its wearer and only its wearer, public goods, like pollution reduction, affect most people. In different terms, nobody can be excluded from “consuming” a public good—or benefiting from its existence. This is not to say that everyone has the same preferences regarding public goods any more than people have the same preferences for private goods. I happen to prefer apples to oranges, and I value pollution reduction more than I value so-called national defense. Other people place greater value on national defense than they do on pollution reduction, just as some prefer oranges to apples. But unlike the case of apples and oranges, where those of us who prefer apples can buy more apples and those who like oranges more can buy more oranges, all U.S. citizens have to “consume” the same amount of federal spending on the military and on pollution reduction. We cannot provide more military spending for U.S. citizens who value that public good more, and more pollution reduction for U.S. citizens who value the environment more.2 Whereas different Americans can consume different amounts of private goods, we all must live in the same “public good world.”

What would happen if we left the decision about how much of our scarce productive resources to devote to producing public goods to the free market? Markets only provide goods for which there is what economists call “effective demand”—that is, buyers willing and able to put their money where their mouth is. But what incentive is there for a buyer to pay for a public good? First of all, no matter how much I value the public good, I only enjoy a tiny fraction of the overall or social benefit that comes from having more of it since I cannot exclude others who do not pay for it from benefiting as well. In different terms: Social rationality demands that an individual purchase a public good up to the point where the cost of the last unit she purchased is as great as the benefits enjoyed by all who benefit, in sum total, from her purchase of the good. But it is only rational for an individual to buy a public good up to the point where the cost of the last unit she purchased is as great as the benefit she herself enjoys from the good. When an individual buys public goods in a free market, she has no incentive to take the benefits others enjoy when she purchases public goods into account when she decides how much to buy. Consequently, she demands far less than is socially efficient, if she purchases any at all. When many behave in this individually rational way market demand grossly underrepresents the marginal social benefit of public goods, and consequently very little public goods will be provided.

Another way to see the problem is to recognize that each potential buyer of a public good has an incentive to wait and hope that someone else will buy the public good. A patient buyer can “ride for free” on the purchases of others since nonpayers cannot be excluded from benefiting from public goods. But if everyone is waiting for someone else to plunk down his hard-earned income for a public good, nobody will demonstrate effective demand for public goods in the market place. Free riding is individually rational in the case of public goods—but leads to an effective demand for public goods that grossly underestimates their true social benefit, and consequently, if left to the market, far too few public goods will be produced.

But what prevents a group of people who will benefit from a public good from banding together to express their demand for the good collectively? The problem is that there is an incentive for people to lie about how much they benefit. If the associations of public good consumers are voluntary, no matter how much I truly benefit from a public good, I am better off pretending I do not benefit at all. Then I can decline membership in the association and avoid paying anything, knowing full well that I will, in fact, benefit from its existence nonetheless. If the associations are not voluntary—that is, if a government “drafts” people into the public good-consuming coalition—there is still an incentive for people to underrepresent the degree to which they benefit if assessments are based on degree of benefit. This is where the fact that not all people do benefit equally from different kinds of public goods becomes an important part of the problem. If we knew that everyone truly valued a large military to the same extent, there would be few objections to making everyone contribute the same amount to pay for it. But there is every reason to believe this is not the case. In this context, if we believe that payments should be related to the degree to which someone benefits, there is an incentive for individuals to pretend they benefit less than they do. If the effective demand expressed by the nonvoluntary consuming coalition is based on these individually rational underrepresentations, it will still significantly underrepresent the true social benefits people enjoy from the public good, and consequently effective demand, and therefore supply, will still be less than the socially efficient or optimal amount of the public good.

In sum, because of what economists call the free-rider incentive problem, as well as the transaction costs of organizing and managing a coalition of public good consumers, market demand predictably underrepresents the true social benefits that come from consumption of public goods. If the production of a public good entails no external effects so that the market supply curve accurately represents the MSC of producing the public good, then since market demand will lie considerably under the true MSB curve for the public good, the market equilibrium level of production and consumption will be significantly less than the socially efficient level, as shown in Figure 4.2, where the market equilibrium outcome, A(M), is considerably less than the socially efficient outcome, A(0). In conclusion, if it were left to the free market and voluntary associations, precious little, if any, of our scarce productive resources would be used to produce public goods no matter how valuable they really are. As Robert Heilbroner (1989) put it: “The market has a keen ear for private wants, but a deaf ear for public needs.”

But what does all this have to do with environmental protection? Reducing pollution, or acting to protect the environment in any way, is providing a public good. Since everyone benefits from pollution cleanup, and everyone benefits from environmental protection, and nobody can be excluded from the benefits of cleaning up pollution or protecting the environment, reducing pollution and protecting the environment are public goods like good A in Figure 4.2. Consequently, there is an incentive for everyone who benefits from pollution reduction or environmental protection to avoid paying the cost of providing it and instead to ride for free on the purchases of others. But of course, when individuals pursue their individually rational strategy and ride for free, there is little or no demand in the market for pollution reduction or environmental protection even when the social benefit is quite large.

Markets provide incentives for individuals to express their desires for private goods in the marketplace by offering to buy them since otherwise they cannot benefit. But markets provide no incentives for individuals to express their desires for public goods in the marketplace by offering to purchase them. Quite the contrary, in a market economy it is almost always foolish for individuals to buy public goods no matter how much they may value or want them. And therein lies the problem with green consumerism in market economies. The problem is not that when people choose to engage in green consumerism the world is not better off because of it. The problem is that markets penalize those who practice green consumerism and reward those who do not, which means that socially beneficial campaigns encouraging green consumption must always swim upstream in market economies.

There are a number of cheap detergents that get my wash very clean but cause considerable water pollution. “Green” detergents, on the other hand, are more expensive and leave my white bedsheets more gray than white, but cause less water pollution. Whether or not I end up making the socially responsible choice, because pollution reduction is a public good the market provides too little incentive for me to make the socially efficient choice. My own best interests are served by weighing the disadvantage of the extra cost and grayer sheets to me against the advantage to me of the diminution in water pollution that would result if I use the green detergent. But presumably there are many others besides me who also benefit from the cleaner water if I buy the green detergent—which is precisely why we think of “buying green” as socially responsible behavior. Unfortunately, the market provides no incentive for me to take their benefit into account. Worse still, if I suspect that other consumers consult only their own interests when they choose which detergent to buy—that is, if I think they will ignore the benefits to me and others if they choose the green detergent—by choosing to take their interests into account and consuming green myself, I risk not only making a choice that was detrimental to my own interests, I risk feeling like a sucker as well.3

This is not to say that many people will not choose to “do the right thing” and “consume green” in any case. Moreover, there may be incentives other than the socially counterproductive market incentives that may overcome the market disincentive to consume green. The fact that I teach environmental economics and fear my students would view me as a hypocrite if they saw me with a polluting detergent in my shopping basket in the checkout line at the supermarket is apparently a powerful enough incentive in my own case to lead me to buy a green detergent despite the market disincentive to do so. (Admittedly, I have only a slight preference for white over gray sheets, and who knows how long I will hold out if the price differential increases?) But the point is that because pollution reduction is a public good, market incentives are perverse, leading people to consume less “green” and more “dirty” than is socially efficient. The extent to which people ignore perverse market incentives and act on the basis of concern for the environment, concern for others, including future generations, or in response to nonmarket, social incentives such as fear of ostracism is important for the environment and the social interest, but does not make the market incentives any less perverse.

Much of the natural environment is what was traditionally called a common property resource, which nobody owns yet all are free to use. The term now preferred by many specialists is common pool resource (CPR), since the defining characteristic is that all have free access to use or exploit the “pool” or resource, whereas the term property indicates that some agent, even if not a private owner, may have the right to deny access to the pool. In any case, ocean fisheries, the upper atmosphere where greenhouse gases are stored, the lower atmosphere where smog and local pollutants accumulate, groundwater aquifers, and large tracts of land whose titles are either nonexistent or unenforced are examples of important common pool resources. Mainstream environmental economists often illustrate the problem Garrett Hardin (1968) made famous as the “tragedy of the commons” by exploring incentives for fishermen.

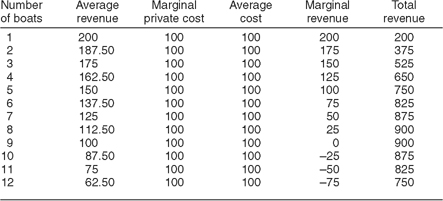

Imagine there are twelve salmon fishermen with boats moored at Friday Harbor on San Juan Island in Washington State. Suppose it costs $100 per day in fuel and wages to operate a salmon fishing boat and there are no other costs. For simplicity we assume the catch out of Friday Harbor is small compared to the total catch in the Salish Sea so the price of salmon is independent of the number caught by the twelve fishermen who fish off San Juan Island. But as more and more boats go out to fish in the same school of salmon, they get in each other’s way and the number of salmon caught per boat declines. Suppose the revenues from selling the salmon catch depend on the number of boats that go out each day, as indicated in Table 4.1.

How many fishing boats will go out each day if all boats have free access—that is, if there is nothing preventing a boat captain from going out if he wants to? To answer this and further questions, we can complete Table 4.1 by calculating some additional columns. If every fisherman is equally equipped and competent, each would expect to catch the same amount as all others fishing that day and therefore expect to get the average revenue from the sale of the fish as his own expected revenue. We calculate the average revenue (AR) by dividing the total revenue (TR) by the number of boats fishing. What a profit-maximizing captain would compare this expected revenue to would be the cost of fishing for the day, which is $100 for each and every boat no matter how many other boats are fishing. In other words, the MPC, to a boat captain of fishing for the day is $100, and as long as the expected AR of fishing is at least as high as the MPC of fishing, we would expect profit-maximizing captains to go out if they have “free access” to the fishery.

When trying to think like a captain, imagine you have picked up your crew in your truck, and when you get to the dock you assume that everyone else who is going to fish that day has already gone out. You can count how many boats are still there and therefore calculate how many have already gone out. For example, if you arrive and six boats are still at the dock, that means six boats have already set sail, and you assume that if you go out there will be seven boats fishing that day. Your decision is whether to go fish or walk back to the tavern with your crew and spend the day playing pool and telling fish stories. If you do not go out, you do not have to pay for fuel and you owe your crew nothing. Along with AR, MPC, and TR, Table 4.2 lists average cost (AC) and marginal revenue (MR), the change in TR because an additional boat went out fishing. The values of some of these variables change when the number of boats fishing changes while others do not.

Table 4.1

Total Revenues in the San Juan Island Fishery

| Number of fishing boats | Total revenues from catch (in $) |

| 1 | 200 |

| 2 | 375 |

| 3 | 525 |

| 4 | 650 |

| 5 | 750 |

| 6 | 825 |

| 7 | 875 |

| 8 | 900 |

| 9 | 900 |

| 10 | 875 |

| 11 | 825 |

| 12 | 750 |

The first captain will go out because he will expect to get $200 in revenues and spend only $100 in costs. The second captain to arrive at the dock will also go out because he will expect to get $187.50 for $100 in expenses. What about the captain who sees that seven boats are already out, meaning he would be the eighth? With eight boats fishing, he expects to get $112.50 for $100 in costs. If the next captain arriving at the dock thinks he is a little more skillful than the average captain, he will go out too because the expected revenue if he were only of average skill would be $100, which would pay for the $100 in costs. So the number of boats we expect to go fishing under free access is nine. The captain who arrives and sees that nine boats are already out fishing will head straight for the tavern that day since he cannot expect to cover $100 in fuel and labor costs with $87.50 in revenues—which is what each captain gets when there are ten boats fishing. The eleventh and twelfth late sleepers will turn back for the tavern even quicker.

Table 4.2

Average and Marginal Costs and Revenues in the San Juan Island Fishery (in $)

But how much does the last boat that goes out fishing under free access increase TR from the catch? Economists call the change in TR when one more boat is added to the fishing fleet for the day the MR. MR is calculated in Table 4.2 by subtracting the TR in the previous row from the TR in the row we are looking at, since that is the change in revenues that came from adding another boat to the fishing fleet. So another way of asking the above question is to ask what MR was when the last boat went out fishing. The increase in TRs from the ninth boat is $0 since eight boats will catch $900 worth of fish just as nine boats do!—which illustrates the logic of overexploitation nicely. Clearly too many boats will fish each day.

If you have ever seen commercial fishermen racing each other to find the school of fish and cutting in on each other once the school is located, you will understand how at some point another boat does not increase the number of fish caught. This is true for grazing livestock, timber harvesting, and pumping oil in common pool resources as well. Notice that the ninth boat went out because its captain hoped to earn a small profit, even though the extra boat adds $100 in labor and fuel costs to the overall fishing effort while contributing nothing to benefits resulting from the overall fishing effort since $900 worth of salmon will be caught whether there are eight or nine boats fishing. If the cost of operating a fishing boat dropped to $85 per day, ten boats would go out under free access. Notice how counterproductive individual rationality is under free access in this case. The tenth boat will go out because the captain expects to get $87.50 while only spending $85. But by doing so he adds $100 to the overall cost of the fishing effort and reduces total fish revenues by $25!

Garrett Hardin (1968) called this outcome the “tragedy of the commons.” Natural resource economists study this phenomenon as a “perverse incentive” that leads to “overexploitation” of the commons under a system of free access. If we apply cost-benefit analysis (CBA) to determine the efficient, or optimal, level of exploitation when MPC is $100, we would send out no more than five boats to fish every day because once five boats are fishing the additional revenue from sending more boats, MR, is less than the additional cost of sending more boats, MPC = $100. In conclusion, the socially rational level of exploitation is for five boats to fish every day, but under free access there is a perverse incentive that makes it individually rational for nine fishermen to go out every day, meaning that the fishery will be “overexploited” under free access.

In this overly simple model there is only one time period and consequently no future to worry about. In this case the only negative external effect of an additional boat fishing is that the other boats fishing that same day all catch less fish than before for a given amount of effort on their part. Since there is no incentive for individual captains to take this negative external effect into account, our model predicts that too many boats will fish on a given day—nine instead of five. But in the real world there is a future, and fish caught today are fish that are not available to be caught next year. Moreover, when more fish are caught today, there will be fewer fish to reproduce and therefore even fewer fish to catch in the future. When people think about overexploitation of fisheries, they naturally think of overfishing to extinction. It is noteworthy that even a single-period model, which does not account for negative external effects from fishing today that occur in the future, predicts overexploitation.

A more complicated and realistic model with two time periods and a fish reproduction rate would predict that overexploitation under free access is even more severe because such a model would account for three, instead of only one, negative external effects that each captain has no incentive to take into account: (1) The more fish any captain catches from a fishery, the fewer fish others will catch for a given amount of effort this year. This is the effect captured in our simple, one-time-period model, which leads to the conclusion of “overexploitation” in the sense that net benefits from fishing will be less this year than they would have been had fewer boats spent less time fishing. (2) The more fish any boat catches this year, the fewer fish will be available for all fishermen to catch next year. This negative external effect implies that net benefits during the two years together would have been higher had fewer fish been caught this year and more of these same fish caught next year. This effect would be captured in a two-time-period model. (3) The more fish any boat catches this year, the fewer fish will reproduce, and therefore the fewer fish will be available to be caught eventually. This negative external effect can be captured in a model with a multiperiod future, a reproduction rate, and a maturation rate. It implies that compared to the exploitation pattern from free access, net benefits over time would be higher if even fewer fish were caught in early time periods, thus allowing for more reproduction and larger catches in later time periods.

In Chapter 7 we explore policies to try to solve this problem. Besides privatization of CPRs, in this case having one fisherman buy up exclusive rights to the San Juan fishery, and regulation of CPRs, in this case having the Washington State or San Juan County government sell fishing licenses, we will explore the logic of a long ignored alternative—community self-management of CPRs.

We take up the subject of climate change in great depth in Part IV. But it is instructive to pause here briefly and notice how all three of the above problems with market systems play an important role in causing climate change and obstructing its solution. Human economic activity over the past 100 years has led to dramatic increases in atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide. Between 1860 and 1990, global carbon emissions rose from less than 200 million to almost 6 billion metric tons per year. At the same time, deforestation has considerably reduced the recycling of carbon dioxide into oxygen. The result of increased carbon emissions and reduced sequestration—taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere by converting it to oxygen—is that the stock of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has increased to the point where it is leading to climate change with serious adverse affects. At its old equilibrium level, the greenhouse effect was part of making the earth inhabitable, preventing the earth’s mean temperature from falling well below freezing and reducing temperature fluctuation between day and night. But today’s higher levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere mean global temperatures will rise and extreme climate conditions will intensify. Droughts will be longer, floods more severe, hurricanes and tornadoes more frequent, and melting polar ice caps will raise sea levels and threaten a large percentage of the world’s population who live in coastal cities.

This is happening because businesses and households that burn fossil fuels are not charged for the adverse effects of their actions on the atmosphere—carbon emissions are a negative externality. It is happening because those who control tropical forests are not paid for the beneficial effect of carbon sequestration if they choose to preserve the forests—carbon sequestration is a positive externality. And as explained, markets create perverse incentives for businesses and households to engage in too many activities with negative external effects and too few activities with positive external effects. The upper atmosphere where greenhouse gases are stored is a CPR resource to which all have long had free access. As we have seen, there are perverse incentives for users to overexploit CPRs under free access. And, finally, those who reduce carbon emissions provide a public good, as do those who preserve forests that sequester and store carbon. But as explained, since no one can be excluded from benefiting from these public goods, and they do entail private sacrifices for those who provide them, all businesses, consumers, and nations wait for someone else to shoulder the burden of providing these public goods in hopes of riding for free on the sacrifices of others. Everyone wants to continue to enjoy the benefits associated with carbon-emitting activity and hopes that others will reduce their carbon emissions. For all these reasons, it should come as no surprise that too much burning of fossil fuel, too little preservation of forests, and too little reduction of carbon emissions goes on in market economies. Nor is it hard to see why international negotiations over ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase forest conservation keep getting stuck.

Decision-making by private owners of natural resources under the pressure of market competition often leads to decisions based on a rate of time discount that is higher than can be justified for social decision-making purposes. When this is the case, resources are extracted faster than would be socially efficient. But the reasons for this unfortunate outcome are not as simple as often believed.

When I decide how to weigh well-being now versus well-being next year, it is sensible for me to take into account the non-zero probability that I might be dead next year. What is more, there is a probability of one that I will be dead 100 years from now, so whatever benefits might be made possible 100 years hence by my forgoing benefits today would presumably not matter to me at all. These calculations imply that it is rational for a mortal being to discount well-being in the future compared to well-being now. For example, if I discount a dollar’s worth of benefits next year by 10 percent compared to a dollar’s worth of benefits right now, my personal rate of time discount is 10 percent.

On the other hand, there is a zero probability that there will be no human beings living next year. And while the probability that there will be no humans alive 100 years from now may not be zero, the probability is much less than one. So, unless we simply do not care as much about the well-being of future generations as we do about our own, there would seem to be no justifiable reason for society to discount human well-being in the future compared to human well-being now when making decisions about how to use the natural environment. Or so it first appears. Moreover, since mortal humans presumably make decisions based on their individual interests, it would also appear that the rate of time discount individuals will use when comparing present and future costs and benefits will be higher than the rate of time discount humans should use as a species that hopes to survive many generations.

But first appearances are sometimes deceiving. Suppose I own a mineral deposit that can be exploited this year or next year. If I know I will be alive both years and intend to exploit the deposit myself, I would be foolish to extract any ore this year that would be more valuable if extracted next year instead. But what if I do not expect to live past this year? Should I extract all the ore now since I will not be around to benefit from the profits from extraction next year? In a private enterprise market economy, the answer turns out to be “no.” Suppose I am only interested in how much I can get from the deposit this year before I die. Rather than use an inefficient one-year extraction plan myself, I should sell the deposit to someone who will be alive for two years for a price that reflects the profits that can be earned from the deposit under a more efficient, two-year extraction plan. As we have just seen, if I do not own the deposit but only have user’s rights, I will be tempted to overexploit it myself before I die. But if I own the deposit and can sell it to someone who will live two years and make the most profitable use of it, then individual mortality need not lead to overexploitation. By extension, since users today know there will be people who will pay for the ore indefinitely into the future, the price of the mineral asset should reflect its most valuable use over time, and whoever is the user should be forced to adopt the most socially useful pattern of exploitation in order to justify the price paid for the asset.

Thus, many natural resource economists argue that contrary to first appearances, even when natural resources are privately owned by mortals, as long as these assets can be bought and sold there is no perverse incentive to extract them faster than is efficient. The self-interest of resource owners protects the interests of future generations because the resource owners would earn lower profits by ignoring those who will be willing to pay for the resources tomorrow. In effect, today’s market for natural resources gives unborn consumers as well as today’s consumers votes about when to extract our natural resources.

So where is the problem? Why do decisions made in competitive market environments use a rate of time discount that is too high when deciding how fast to extract natural resources? Two reasons conspire to make the rate of time discount that is sensible for private resource owners to use when deciding how fast to extract the resources they own significantly higher than the rate of time discount that society can justify for itself on ethical grounds—future market failures, and profit rates in excess of the growth rate of net welfare per capita.

Future market failures: Since uncertainty is cumulative over time, there is a greater degree of market failure in markets for goods and services delivered in the future, or what are called “futures” markets, than there is in markets for goods and services now, or what we might call “present” markets. For example, finding a market for oil to be delivered twenty-five years from now is harder than finding a market for oil to be delivered this month, and if you do, the oil futures market is not likely to be as “well ordered.” Futures markets tend to be “thinner”—have fewer participants—with wider and less predictable price fluctuations. But greater “market incompleteness” in futures markets means that, on average, you are more likely to be paid the full benefit of a good or service delivered today than the full benefit that will come from delivery of the same good or service in the future. In other words, the greater degree of market failure in futures markets means that market economies treat goods today as more valuable “birds in the hand” and goods in the future as less valuable “birds in the bush” even though future generations will value their birds as much as we value ours today.

A rate of time discount that is too high: Contrary to our preliminary conclusion above—that unless we favor present over future generations, the rate of time discount we use for social decision-making should be zero—a reasonable case can be made for discounting future net economic benefits compared to present net economic benefits if net national welfare per capita is growing. If we interpret intergenerational equity as an equal opportunity to enjoy economic welfare irrespective of generation, future welfare should be discounted by the expected rate of growth in per capita economic welfare. The idea is simple: If future generations are going to enjoy greater economic well-being than we do, then the same amount of economic well-being delivered now should count for more than if it is delivered later. According to this logic, a social rate of time discount equal to the rate of growth of per capita net national economic welfare is perfectly fair.

Eban Goodstein defines net national welfare (NNW) as the value of “both market and non-market goods and services produced minus the depreciation of capital, both natural and human made, used up in production, minus the total externality costs associated with these products” (1995, 63). At least in the first world, per capita net national product (NNP) has grown over the past 200 years. However, as discussed in Chapter 3, NNP per capita overestimates NNW per capita because it does not take into account the depreciation of natural capital or the production of harmful wastes as by-products of producing useful goods and services, both of which have been increasing. So using the growth rate of per capita NNP rather than NNW overdiscounts the future. Some empirical estimates of the rate of growth of per capita NNW compared to NNP are informative, even if they disagree to some extent. Nordhaus and Tobin (1972) estimate that per capita NNP in the United States had grown by 1.7 percent from 1929 to 1965 while per capita NNW had grown only by 1.0 percent. Daly and Cobb (1989) estimate a dramatic increase in the difference between the rate of growth of per capita NNP and NNW over the past forty years in the United States. For 1950–1960, Daly and Cobb estimate that per capita NNP grew by 1 percent per year while per capita NNW grew by 0.8 percent per year. And for 1960–1970, they estimate that per capita NNP grew by 2.6 percent per year while per capita NNW grew by 2.0 percent. However, for 1970–1980, they estimate that while per capita NNP grew by 2.0 percent per year, per capita NNW fell by 0.1 percent per year. And for 1980–1986, they estimate that per capita NNP grew by 1.8 percent per year while per capita NNW fell by 1.3 percent per year.

The possibility that per capita NNW may now be falling instead of rising is certainly alarming. If this is the case, it implies that instead of discounting future net benefits we should be discounting net benefits in the present when doing CBA or when calculating how fast to extract scarce natural resources. However, the relevant question with regard to resource extraction is how the rate of growth of NNW per capita compares to the average rate of profit in the economy, because the average rate of profit in the economy is the logical discount rate for private owners of natural resources to use when discounting future benefits from extraction compared to present benefits from extraction. If the average rate of profit is higher than the rate of increase of NNW per capita, then private resource owners will be driven by market competition to extract natural resources more quickly than is socially efficient.

During the past twenty-five years, profit rates on average have been two to three times higher than the growth rate of per capita NNP and four to five times higher than any estimates of the growth rate of per capita NNW. The reason is simple: The rate of profit is determined not only by how fast NNP—not NNW—grows, but also by how the net product is divided between employers and employees. The greater the bargaining power of employers versus employees, the more the rate of profit will exceed the growth rate of NNP.

This is easy to see by imagining a capitalist economy that is productive but not growing. An economy is “productive” if it is capable of replacing all the produced inputs it uses in production and still has a positive net product, or “surplus,” left over. Unless the workers consume the entire net product, some of the surplus will be left over for employers as profits. So unless the workers are all-powerful and manage to keep all of the surplus, the ratio of the value of the net product left over for employers divided by the value of the goods capitalists advanced for the production process—that is, the rate of profit—must be positive, and greater than the rate of growth of NNP, which we stipulated by assumption to be zero. It can be shown that (1) there is a maximum rate of profit that corresponds to a wage rate of zero, (2) there is a maximum wage rate that gives workers the entire net product, which corresponds to a profit rate of zero, and (3) between these two extremes, the rate of profit is always positive and inversely related to the wage rate (Hahnel 2002, chapter 5). But all real-world capitalist economies must operate between the two extremes since workers would refuse to be workers in the first extreme, and capitalists would refuse to be capitalists in the second extreme. So profit rates would always be positive in capitalist economies even if the growth rate were zero. Analogous theorems for a growing economy prove that normal rates of profit will always exceed growth rates of NNP (Roemer 1981, chapter 4).

Since two of the most salient features of the global economy over the past thirty years are the escalating degradation of the natural environment and the increasing power of capitalists vis-à-vis workers on a world scale, the rate of growth of per capita NNW is declining relative to the rate of growth of NNP, and the normal rate of profit is rising compared to the rate of growth of NNP. Consequently, private owners of natural resources are not only discounting the benefits of leaving resources in the ground to be available for extraction in the future too much, but they have been overdiscounting to a greater and greater extent.

In sum, despite first impressions, the fact that individual humans are mortal while the human species is less so does not lead private owners to extract natural resources faster than can be ethically justified. However, because future markets are usually thinner and because the average rate of profit has been substantially higher than the rate of growth of net national economic welfare per capita, private owners of natural resources have been driven by competitive conditions to extract natural resources far faster than has been socially efficient for quite some time.

1. See Hunt and D’Arge (1973) for an eloquent criticism of the presumption that externalities are exceptions, rather than the rule.

2. People can, and sometimes do, vote with their feet by moving to states and localities that provide a mix of local public goods more to their liking. However, this does not solve the problem for public goods provided at the national level.

3. Most detergents call for a full cup per load of wash. Church & Dwight canceled a quarter-cup laundry detergent when consumer demand for this “green” product proved insufficient (Canning 1996).