8

Mapping your growth direction

“And she’s buying a stairway to heaven”

Led Zeppelin

• A compelling growth strategy is one that is clear about which cylinders will drive growth in each time horizon

• Plotting the cylinders horizon by horizon yields nine “how to” strategies that can be used to define alternative growth paths

• The growth map provides a structure for setting and communicating a growth direction and charting the actions for pursuing it

IN

THE ALCHEMY OF GROWTH we introduced the “three horizons” framework to help business leaders look ten or more years ahead when they are formulating and articulating their growth direction. We argued that companies seeking sustained and profitable growth need a pipeline of business creation that comprises actions across all three horizons at once (

Figure 8.1), and we described how the horizons could be cascaded down to leaders at all levels in an organization.

The point of the three horizons was to encourage and assist executives to evolve their portfolios over time. Since we introduced the framework, companies have adopted it to make a thorough analysis of their strategic opportunities so as to arrive at the right growth themes. Unfortunately, though, we have seen many organizations (and their advisers) use our framework loosely and thus arrive at growth strategies that aren’t sufficiently robust.

To avoid this problem, companies need to assess how their sources of advantage in each of the three cylinders match the granular opportunities in the marketplace. Fair enough, you may think, but how do you figure it all out? We have developed a new tool, the growth map, to help with this task. It provides a much more disciplined way of approaching the three horizons framework.

The growth map

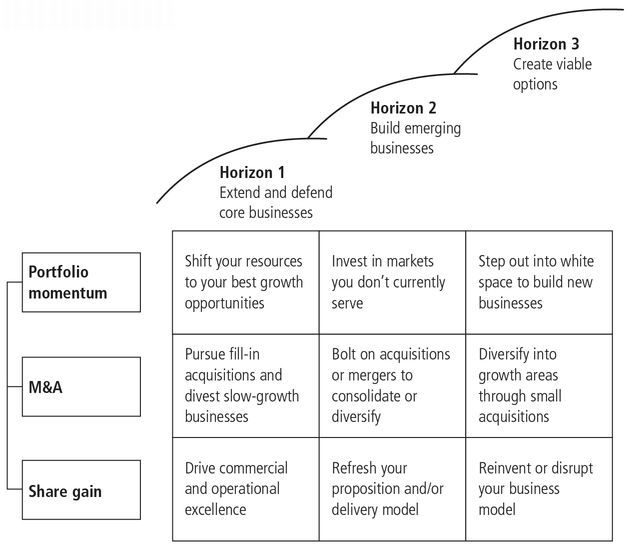

As we’ve seen in the last three chapters, each of the three cylinders can be used to drive growth in a company. If we combine the three cylinders with the three horizons framework, we arrive at the growth map: a tool for ensuring that we apply the necessary rigor when we set our growth direction and for charting the actions we must take to pursue it.

Let’s take a look at the growth map illustrated in

Figure 8.2. The columns in the grid correspond to the three horizons of growth. It’s important to note that the “clock” for the horizons will differ from company to company. If you’re in a hyper-growth market such as consumer electronics, horizon 3 may be only a couple of years away; if you’re in a slow-moving resource industry, on the other hand, you may not see horizon 3 initiatives become mature businesses for a decade or more. This means that you’ll need to form a view on the right timing of horizons for your organization and markets

before you start to set your growth direction.

1

The rows in the grid correspond to the three growth cylinders we explored in previous chapters. The benefit of mapping cylinders against horizons is that it forces you to think clearly about how to deliver growth over time. How will you use portfolio momentum, M&A, and share gain to extend and defend your core businesses in the near term? How will firing on the three cylinders build your emerging businesses in the medium term? And how will you create viable options for the long term? Will your growth direction lead you to fire on more cylinders in years to come?

To answer these questions, you’ll need to form objective, dispassionate judgments about your sources of advantage horizon by horizon. This is becoming more and more difficult for large companies to do well. You should include a broad set of competitors in your reference class: for instance, include private-equity firms in the reference class you use to evaluate your M&A cylinder. What you may regard as a clear source of advantage may, when put to the test, turn out to be no such thing.

The growth map helps you to compare different options for improving your cylinder firing on the basis of your source of advantage, and to assess how effectively these options will drive revenue growth in each horizon. We’ve already taken a cylinder view of your growth direction in previous chapters; let’s now work systematically through the growth map to see how it can help you set your growth direction horizon by horizon.

Horizon 1: Extend and defend core businesses

As we saw in The Alchemy of Growth, horizon 1 is concerned with the heart of the organization—the businesses that customers and analysts identify with the corporate name. These are core businesses for a reason: they drive nearterm performance and account for most of the profits and cash flow that will provide the resources necessary for growth.

But how should you extend and defend your core businesses? More specifically, which cylinder(s) will drive your growth in horizon 1? Let’s look at the opportunities cylinder by cylinder.

•

Portfolio momentum: Shift your resources to your best growth opportunities. Companies can use their resource allocation to boost portfolio momentum in the short term. Redeploying investment dollars, leadership talent, and even decision-making authority to the units with the highest growth potential helps put the weight of the organization behind raising the average growth rate. With additional resources, these units can accelerate their growth in critical markets (especially in fast-growing countries). New studies show that reallocating resources is a relatively under-utilized lever in large companies.

2 One of our pharmaceutical clients recently reorganized one of its country operations to reflect the decline in the influence of physicians and the increase in the influence of pharmacies. Despite much resistance, the physician sales force was cut by 30 percent and resources were redirected to a new dedicated pharmacy team.

• M&A: Pursue fill-in acquisitions and divest slow-growth businesses. The M&A action plan in horizon 1 typically consists of supplementary acquisitions that deepen the positional advantage of a company’s existing businesses. These acquisitions may round out a product offering, supply missing capabilities, or otherwise protect the business from competitors. One of our telecom clients recognized it had a gap in its distribution capabilities as it moved from selling mostly mobile products via retail outlets and call centers to selling broadband. It needed a door-to-door salesforce that could reach critical mass quickly; acquisition was the logical way to fill the gap.

•

Share gain: Drive commercial and operational excellence. Though keeping up with the competition is critical to profitable growth, market-share outperformance is often difficult to achieve in horizon 1. As we argued in chapter 7, it typically involves improving basic execution or leveraging a business-model advantage to compete hard for share across all segments.

3 In the short term, a company can pull a number of tactical levers to affect market share, such as transactional pricing, sales stimulation, and better market segmentation and customer targeting. These are critical levers for improving short-term earnings, but our analysis reveals that they seldom have much impact on a company’s overall growth trajectory.

To illustrate the importance of short-term portfolio-momentum and market-share improvement, let’s look at Delta Airlines. Since late 2005, the company has been switching to smaller aircraft and reducing mainline capacity in its domestic operations, and shifting toward more international flights. It cut domestic capacity in the first half of 2006 by 15 percent and increased international capacity by 20 percent, adding 50 new routes to more than 20 cities. The turnaround has yielded promising early results. For the first half of 2006, revenue from international flights was up by 24 percent on a year earlier, and domestic revenue rose by 5 percent despite the cut in capacity. Delta emerged from bankruptcy in April 2007.

Short-term improvements like those mentioned above can readily be implemented in horizon 1, and often drive both momentum and share gain.

Horizon 2: Build emerging businesses

While horizon 1 addresses the businesses that are at the heart of today’s organization, horizon 2 looks at the emerging businesses that may one day transform it. Even though substantial profits may be years away, these businesses should be at the top of any forward-thinking executive’s mind. They may prove to be as profitable as horizon 1 businesses in time.

However, emerging businesses will need considerable investment in both time and capabilities, so the primary focus for horizon 2 should be on building new streams of revenue. Yet this is becoming increasingly difficult for a large company to achieve systematically and repeatedly, as Geoffrey Moore deftly described in a recent

Harvard Business Review article.

4 In the M&A arena, for instance, the rise of private-equity firms and special-purpose acquisition companies has made competition even more intense. Many companies that have squared up to top private-equity firms in an acquisition race and lost are left wondering what they could have done differently.

Let’s now look at the second column in the growth map. Which of the three cylinders will be most powerful in driving your company’s growth in horizon 2?

• Portfolio momentum: Invest in markets you don’t currently serve. Capabilities that have been built up in existing businesses represent a source of advantage that can be exploited to move into new markets. Supermarkets have followed this growth strategy over the years by driving costs out of the supply chain, passing on a share of the savings to consumers through price reductions, and expanding from traditional dry grocery into adjacent categories such as fresh food, alcohol, pharmacy, general merchandise, and even financial services.

•

M&A: Bolt on acquisitions or mergers to consolidate or diversify. The M&A initiatives in horizon 2 tend to involve bigger moves designed to secure advantageous positions in key markets. Acquisitions of compatible businesses or outright mergers can be used to purchase revenue in promising areas, including those in adjacent markets.

Such deals account for many of the big headline-grabbing transactions such as mergers in the oil and pharmaceutical industries and consolidation in the European energy and utilities sector. Take National Grid Transco, a UK-based utility. In 1999, 80 percent of its revenues came from electricity transmission in its home market. The company then dramatically expanded its US presence by making three large acquisitions in two years. It also broadened its domestic portfolio by merging with Lattice Group, a UK gas transmission and distribution company, in 2002. By the end of 2005 its top-line revenues had risen to nearly six times their 1999 total, a CAGR of 34 percent, while TRS had grown at 6 percent. This part of the growth map also includes less conspicuous deals such as acquisitions by big technology companies of small ones with complementary products that can benefit from their sales and marketing clout.

• Share gain: Refresh your proposition and/or delivery model. In order to deliver a sustainable step change in market share in horizon 2, companies need a value proposition that is far superior to that of competitors, as we saw with Dell and Toyota in chapter 7. This involves more than product innovation; it embraces such things as retailers investing in format renewal, technology companies rewiring their salesforces to deliver integrated solutions rather than independent products, and integrated telecom incumbents bundling fixed telephony, mobile, and broadband at a substantial discount.

Horizon 3: Create viable options

Horizon 3 looks beyond emerging businesses to the embryonic options on future growth. These initiatives may be small, but they serve to test possible business activities and investments that may yield profits in the long term. As we discussed in The Alchemy of Growth, horizon 3 initiatives are the research projects, market tests, pilots, alliances, minority stakes, and memoranda of understanding that have the potential to yield businesses with horizon 1 levels of profitability if they prove successful.

Horizon 3 initiatives are not for dreamers, though. Clearly there are any number of possible future endeavors that a company pursuing growth could investigate. The challenge it faces is to nurture those that show promise while dropping those with diminishing potential in a disciplined manner. This may sound reminiscent of what venture capitalists do, but there is an important difference. A company creating viable options in horizon 3 isn’t simply venturing with the intent of seeing a few of its portfolio investments strike gold. Rather, it is making a commitment to build horizon 2 businesses within its chosen arenas over the next few years by learning and taking a series of steps up a staircase.

So which cylinders will drive your growth in horizon 3?

•

Portfolio momentum: Step out into white space to build new businesses. Sometimes portfolio moves are triggered by insights about the emergence of an entirely new business segment or the disruption of an existing one. In such cases M&A isn’t an option since the business (or business model) doesn’t yet exist. A company wishing to enter has no choice but to build a new business. One example is an energy company moving into the production of renewable-energy equipment such as fuel cells. Another is Apple’s decision to sell music via its iTunes online store to both Mac and Windows users. This marked an innovative and disruptive business-building move that leveraged a whole set of advantages Apple had acquired through the success of its iPod and computer ranges. The company made a similar move more recently when it entered the mobile telephony market with its iPhone.

As we saw in chapter 5, improving your portfolio momentum often takes time. Companies should bear this in mind when they make their horizon 2 and, particularly, horizon 3 investments.

• M&A: Diversify into growth areas through small acquisitions. In horizon 3, M&A moves are typically smaller and more measured. They involve forays into uncertain terrain where attackers are deploying new business models that disrupt the economics and positional advantage of traditional incumbent businesses. These forays can be viewed as important first steps along the path to future growth strategies. Some companies have accepted that the market is better than any individual company at innovating, and that buying early-stage businesses can be a better investment than backing internal R&D or business-building efforts. In accordance with this belief, they operate large business-development teams that build deep relationships with venture capitalists, academic institutions, and research communities to identify new opportunities early and establish a position as the preferred partner for commercialization.

•

Share gain: Reinvent or disrupt your business model. A reshaped business model is likely to take some time to produce share gains.

5 And few large companies are good at disrupting their own markets at the likely cost of product cannibalization, earnings dilution, and channel conflict. It’s no surprise that Amazon was created by a new entrant and not an existing bricks-and-mortar bookstore. When the major airlines introduced their own low-cost carriers in an attempt to emulate the success of discount point-to-point players such as Southwest and Ryanair, they were following this strategy. Most have struggled to pull it off. Yet successful reinventions do happen. A mortgages attacker that had reached the limits of penetration with its own products successfully reinvented itself as a mortgage broker to disintermediate the established banks.

Mapping your growth

In

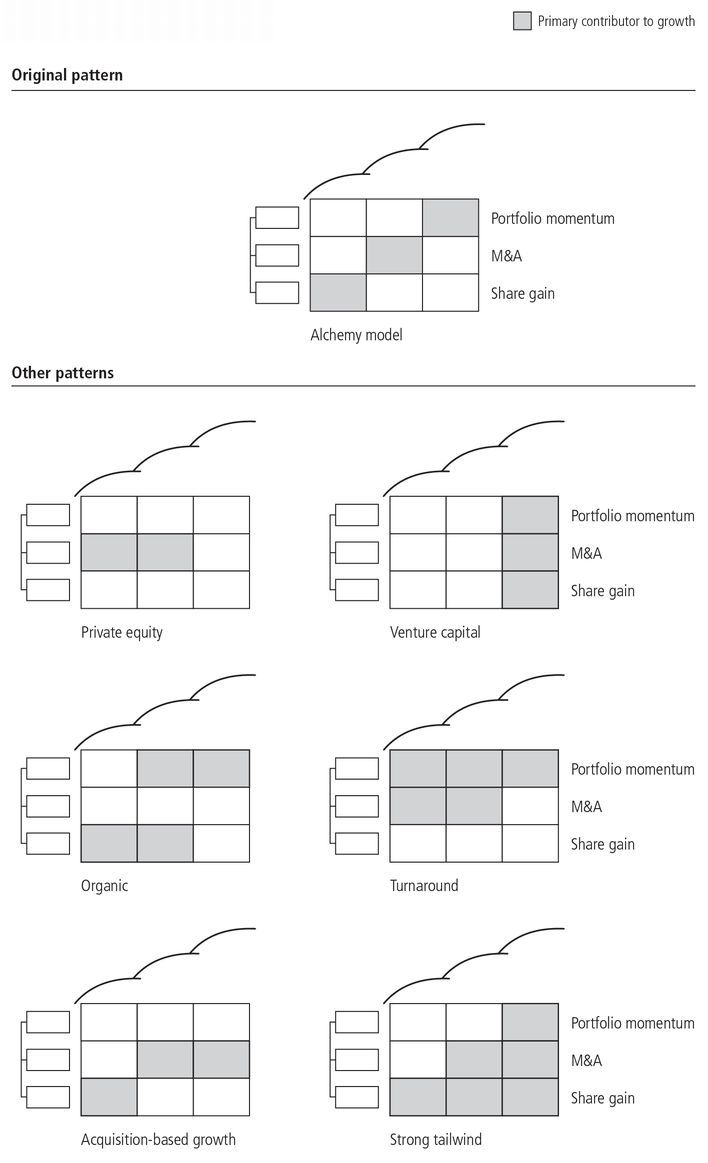

The Alchemy of Growth, we reported the results of our research into thirty great growers. In fact, we derived our three horizons model by analyzing the growth directions and strategies that these companies adopted. By plotting this pattern onto our growth map, we arrive at the classic

Alchemy model shown on the left of

Figure 8.3. Although it didn’t use these specific terms, it emphasized the importance of firing on the market-share gain cylinder in horizon 1, M&A in horizon 2, and momentum in horizon 3.

By adding the three growth cylinders to the three horizons framework, we can go beyond this model to identify various other patterns for companies to consider when choosing their growth direction:

• Private equity. Private-equity firms pursue M&A as an engine of growth in horizons 1 and 2. Because of their preference for scale and leverage of cash flow, they don’t tend to seed M&A options in horizon 3.

• Venture capital. Venture-capital firms pursue horizon 3 investments almost exclusively, but they also actively push the share-gain lever to drive growth in existing investments.

• Organic. Some companies shy away from inorganic growth. In the high-tech sector, for example, many firms drive growth through share gain in horizons 1 and 2, while spending on R&D to create a pipeline in high-momentum areas.

• Turnaround. Companies undergoing a turnaround need to concentrate on shifting their portfolio momentum. They do this in all horizons organically, but also rely on game-changing M&A (including divestments) in horizons 1 and 2.

• Acquisition-based growth. Over the past decade, companies in some growth sectors have become interested in collaborative horizon 3 models. Instead of growing their own options, they acquire their new businesses by working with specialists such as venture-capital firms. This growth pattern resembles the old Alchemy model but with inorganic growth replacing portfolio momentum in horizon 3.

• Strong tailwind. Some companies are carried along by a strong tailwind that helps them make a big growth spurt. Their growth pattern is an additive one: share gain in horizon 1 plus M&A in horizon 2 plus portfolio momentum in horizon 3.

Each of these patterns has a compelling logic in terms of how and why the different cylinders contribute to growth in the different horizons. That, in the end, is the critical test for any growth map. However, this is not an exhaustive list; many other growth directions are possible. In fact, it can be well worth experimenting with alternative growth maps so as to trigger an informed debate about which direction to choose.

We end by quoting Theodore Levitt. He described the first requisite of leadership as knowing precisely where one wants to go and making sure the whole organization knows it too:

“Unless a leader knows where he is going, any road will take him there. If any road is okay, the chief executive might as well pack his attaché case and go fishing. If an organization does not know or care where it is going, it does not need to advertise that fact with a ceremonial figurehead. Everybody will notice it soon enough.”

6His words are as true now as when he wrote them more than 40 years ago, and sound an apt note for today’s leaders as they set a direction for growth.

NOTES

1 For a detailed discussion of how the timing of horizons can vary by context, see

The Alchemy of Growth, chapter 2.

2 In a 2006 UCLA working paper, “The hand of management: Differences in capital investment behavior between multi-business and single-business firms,” D. Bardolet, D. Lovallo, and R. Rumelt found that a significant proportion of company assets yield insufficient profit to cover their cost of capital or sustain growth. The problem is more acute in multi-business firms (39 percent of assets) than in single-business firms (20 percent). These assets could be “seeds” (early growth businesses that show promise) or “weeds” (businesses with limited prospects). Either way, firms should think carefully about resource allocation. In an unpublished study, the same authors found a correlation between capital allocation in the current period and the last of between 0.77 and 0.92, suggesting that firms reallocate resources only to a limited extent, at least in the short term.

3 P&G’s share gain described in chapter 10 is a prime example of this.

4 G. A. Moore, “To succeed in the long term, focus on the middle term,”

Harvard Business Review, July-August 2007, pp. 84-90.

5 For more on this, see, for example, C. M. Christensen,

The Innovator’s Dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail (Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Mass., 1997).Christensen described the specific case for disruption (a paradigm-shifting innovation that redefines the market away from incumbents).

6 T. Levitt,

“Marketing myopia,”

Harvard Business Review, July-August 1960, pp. 45-60.