CHAPTER 13

‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu’s Envelopes

Julia Charlton

Although the distance involved in the artist Tito Zungu’s journey between work and home was relatively short, compared to the trans-country journeys travelled by many mineworkers, for example, his life was nonetheless defined by South Africa’s migrant labour system. His experience therefore overlaps with that of many others. However, Zungu created an art form arising out of his experience that is unique. His renowned, hand-embellished envelopes can be seen as powerful symbols of the journey between rural homestead and urban centre. The envelopes were originally made as literal containers of letters, mechanisms for communicating with correspondents far away. After his work was introduced to the art market, the envelopes came instead to be regarded as artworks, ending their journey as highly sought-after objects in collections around the world.

In 1999, shortly before his death in January 2000, Wits Art Museum (WAM, then the University of the Witwatersrand Art Galleries) approved the purchase of a collection of 46 envelopes, 4 drawings and a diary from the artist. This collection forms part of the Standard Bank African Art Collection holdings of Zungu’s works at WAM, the other items being two drawings that were acquired by the university in 1987. The envelopes have discernibly been sent through the mail; they are franked and creased, the texture worn so soft it resembles fabric, rather than crisp paper. Many have suffered losses from insect damage and some are stained from contact with liquid. All show evidence of wear and tear from having been extensively handled. All have been carefully slit open on one short side to extract the contents; none have had their flaps torn open. The backs of a few have been used for apparently unrelated calculations or scrawls. In addition to the address and postage stamp, 25 of the envelopes, more than half, have meticulous ballpoint pen images of aeroplanes drawn across their front surfaces. There are other images too: a complex image of a ship filling the envelope, a radio, two depict homesteads, others include flowers, foliage or geometric shapes. On many, embellished words and letters form part of the design. Eight envelopes have no drawings at all and do not appear to have been created by the artist.

The materiality of the envelopes reflects the circumstances of their making. The modesty of the materials used – pencil and black, blue, green and red ballpoint pens and occasionally pencil crayon on commercially produced green, pink, blue and white envelopes – corresponds to the artist’s straitened financial circumstances. Most of the envelopes in the collection are the small, rectangular shape still on sale in packs at supermarkets, general dealers and stationery shops. One is an airmail envelope with the characteristic red, white and blue chevron edging (2000.01.12) and three are the extended, long, rectangular shape known as DL (2000.01.19A (see Figure 13.1), 2000.01.25A and 2000.01.45).1

The envelopes represent the earliest part of his production, the period leading up to his introduction into the art market in 1970 and the promotion of his work by Jo Thorpe of the African Art Centre in Durban (which was then known as the South African Institute of Race Relations). This institution played a key role in Zungu’s career trajectory and acclaim, exhibitions, travel, publication, awards and commissions followed.2 His works became bigger and more complex, evolving into highly detailed stand-alone drawings. As a result of contact with professional artists and printmakers in Durban, he started using different materials that were less vulnerable to fading and explored printmaking as a mode of production. His artmaking practice, however, continued to be an activity that was fitted into available free time after hours, whether he was working as a domestic worker in Durban or later, after he returned to Maphumulo (or Mapumulo) in 1993, as a farmer.

Zungu’s envelopes were widely known in the art world, especially after his first solo exhibition at the University of the Witwatersrand Studio Galleries in Johannesburg in 1982. His work had previously been included in group exhibitions in Durban where it had been awarded prizes, but it was after the exhibition of a significant body of work (more than 60 envelopes) that his work became known further afield.3 He continued exhibiting consistently every couple of years from then onwards and was included subsequently in significant art catalogues. Attention was paid to the formal qualities, symbolism and style of the envelopes and the elaborate drawings that he developed. What have not been considered at any length in these art publications, however, are the contents of the envelopes. This component of the WAM collection, in conjunction with the embellished envelopes, is what makes it distinctive and forms the basis of this chapter’s exploration of Zungu’s work as a prism through which to reflect on the artist’s experience of migrancy.

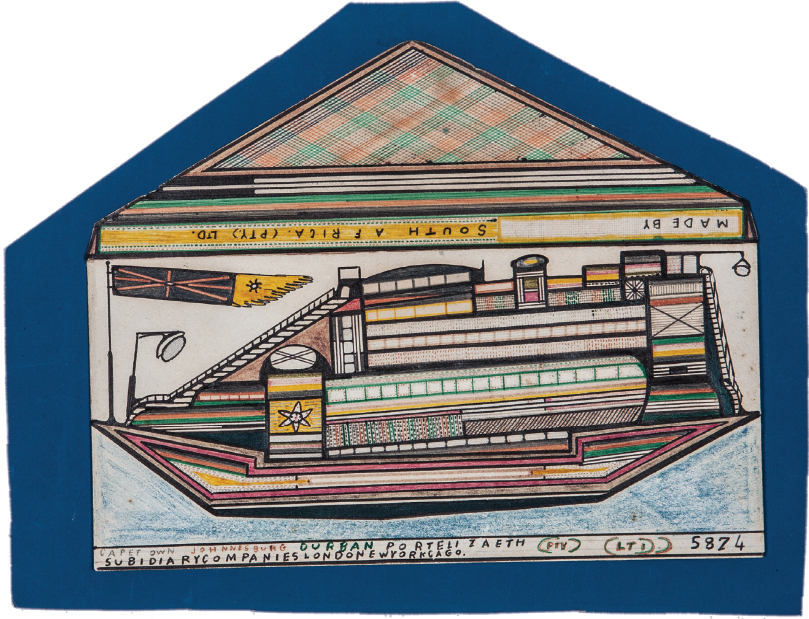

Figure 13.1

Tito Zungu

1968

Ballpoint pen, pencil on envelope

8.8 × 14.9 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

The limitations of the archive need to be noted: only one side of the correspondence is represented and only one letter is from Zungu himself. The rest are from his correspondents, and the context in which they were written is not known. Readers who are tempted to surmise must necessarily risk misinterpretation. The personal nature of the letters also needs to be acknowledged; these are private letters from one person to another and were not intended for publication. The furtive pleasure of reading someone else’s correspondence is undeniable, although the content deals with everyday domestic concerns and there are no salacious details involved. Despite the relatively large amount published on the artist during his lifetime, the letters raise many unanswered questions.4 The relationships between the individuals involved is unknown, but it is clear that Zungu regarded the people who wrote to him as important; he kept their letters for decades and he gave them embellished envelopes to carry their communication to him. This apparent inversion of what might be expected, that the envelopes with Zungu’s drawings would contain letters from him sent to his correspondents, is one of the questions posed by the collection, but the potency of the connection between the parties involved is demonstrable in the investment of time, labour and aesthetic considerations.

Many of the letters (written in isiZulu and translated into English in 2003 as part of my research into the collection) bear no date other than the post office’s stamp on the envelope; the earliest is from 1966 and the most recent from 1975. In some cases, a date seems to have been added on the back by the artist, on receipt of the letter. Zungu kept this correspondence among his personal effects for more than three decades. Many excerpts from the letters have been included in this chapter in recognition of the power of the direct voice of the correspondents. The idiosyncratic grammar has been retained in order to preserve the immediacy of the words and expression. Together with their envelopes, they articulate the condition of Zungu’s journeys.

‘Dear sweetheart wishing you a good life’

Various birth dates have been published for Zungu. In the biography by Jill Addleson and Patricia Khoza in the 1997 retrospective exhibition catalogue, the most substantial publication on the artist, the date is given as 1939, whereas in the biographical handout issued in 2013 by the African Art Centre, the institution most strongly associated with promoting Zungu’s career, and in Steven Sack’s The Neglected Tradition, his year of birth is given as 1946.5 The artist states in ADA (Architecture Design Art) that he does not know when he was born.6 Zungu’s patron Amancio (Pancho) Gueddes estimates in the same volume that the artist was at the time of publication about 40 years old, putting his birth date at about 1946.7 His first name was Nganeziyamhlonipha (‘one who is respected by youths and young women’), but in the art world he is known by the name Tito. This name is derived from another of his names, Deton, and was coined by the Dominican sisters at Walsingham Girls’ Hostel in Durban, where he worked from 1970.

Zungu grew up on a farm in the Maphumulo district, near Stanger (now KwaDukuza), on the north coast of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. He did not receive any formal schooling. Gavin Younge notes: ‘As is common with children born to dispossessed parents in the late 1940s there was no family land left to plough’ and ‘his adolescence was spent working as farmhand and gazing out to sea’.8

Zungu began drawing in the late 1950s and decorated and sold his first envelope for one penny. As his skills improved, his price increased, ‘first to twopence, then a tickey, then sixpence and eventually to twenty cents’.9 Zungu’s initial customers were his friends and family members, who used the envelopes to send letters to loved ones far away. At this time, the postal system was the main vehicle for people to remain in contact. Zungu’s first sale to a collector is recorded as 1960, but his market continued to be primarily his community into the 1970s.10 In 1966, when he was about 20 years old, Zungu moved to the urban centres to find work, initially in Pinetown, then Marianhill and then in Durban. All are approximately 108 kilometres away from his home. He was employed as a domestic worker at various places and gardening, cooking and cleaning are recorded as his occupations. After moving to Durban in 1970, he worked there for the better part of three decades, returning to his home only two or three times a year.

The care and precision necessitated by Zungu’s technique is stressed in various publications. A deeply religious man, he explained the inspiration behind his creating: ‘I am sure that my talent is a gift from God because it is not something I can just sit down and do. I must feel moved to do it. I have sometimes felt frustrated and blank, and have not been able to produce anything.’11 He describes his method as follows: ‘My first drawings in colour pencil were very simple outlines of buildings. I progressed to ballpoint pen’ and further:

I made discoveries as I went along; a red and blue line drawn on each other makes a black one. I therefore used black straight away. Thereafter I used black as the foundation lines. I knew that ballpoint fades with time, so to guard against this I have to draw over the same line several times.

Both Greg Hayes and Colin Richards in the catalogue for the 1997 retrospective exhibition further describe his painstaking practice.12 The envelopes in the WAM collection display the minimal materials and restricted means that characterise the artworks from the early part of Zungu’s career. His initial use of a comb as a drawing implement is visible on some of the envelopes, as well as the ruler he used subsequently.13 In most cases, the drawings occupy a relatively modest area of the envelope. Only in one (2000.01.01, Figure 13.2) does the drawing, a ship flying a flag, extend across the whole surface.14

This envelope was clearly not used to send a letter through the mail. The majority of the envelopes in this collection, though, were intended primarily as conveyers of correspondence, symbolised by the aeroplanes inscribed on the surface, vehicles of speed and sophistication. The other images can also be regarded as symbols of modernity and communication. A radio broadcasts public information and entertainment and logo-like emblems reflect stamps of authorship and authority (2000.01.40A, Figure 13.3).

Zungu retired in 1993 and moved back to Maphumulo where he farmed during the day and continued drawing at night. His wife Ngethusile died in February 1999, after which he too became ill. He died on 11 January 2000 at Doornkop, Maphumulo.

‘Oh well cousin all days are beautiful I would like you to reply’

The Zungu archive at WAM reflects the reliance on and value afforded to the written word and postal communication by both the artist and his correspondents. The community service undertaken by Nokukhanya Luthuli, wife of Albert Luthuli, who delivered letters on foot, is cited by Sue Williamson as evidence of the importance of the postal service among rural residents.15 Luthuli lived in Groutville, about 55 kilometres from Maphumulo, also in the KwaDukuza region and opened a post office for residents of Groutville.16 This commitment reflects the complete dependence on what is now considered ‘snail mail’, easy to underestimate from the vantage point of our current digital era, when email and text messaging are ubiquitous. Cellular technology is now prevalent even among poor communities in the most rural parts of the world. In the 1960s, however, the postal service was essential as a means of communication. One of the earliest letters in the archive, from Shiyabenkami in 1966, in an envelope with an aeroplane drawn across the top left corner, notes: ‘Thank you for an envelope and the stamp so I will not forget replying sometimes I would open the letter quickly hoping that I will get a green writing pad inside the envelope but now I am not going to forget writing’ (2000.01.10B). Wilson Zungu writes in 1969: ‘I am asking you nicely to reply me … I would like you to reply me soon so that I will have more information – hurry up … please write back to me I want to know – reply me my brother. It is me’ (2000.01.29B). This envelope is not adorned, except for the address in purple ink, which is stamped as if from a rubber stamp.

Figure 13.2

Tito Zungu

Not dated

Ballpoint pen, pencil, felt-tip pen, pencil crayon on envelope

14.6 × 18.5 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

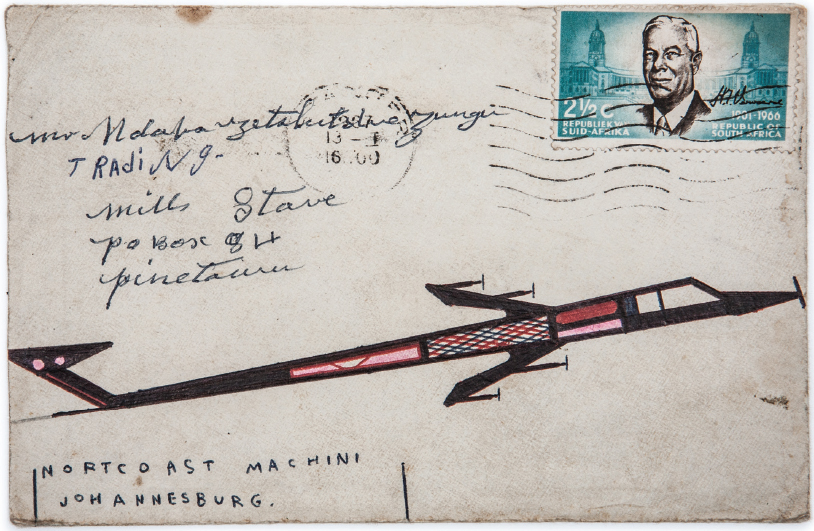

Figure 13.3

Tito Zungu

1973

Ballpoint pen, felt-tip pen, rubber stamps, pencil on envelope

6.2 × 10.9 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

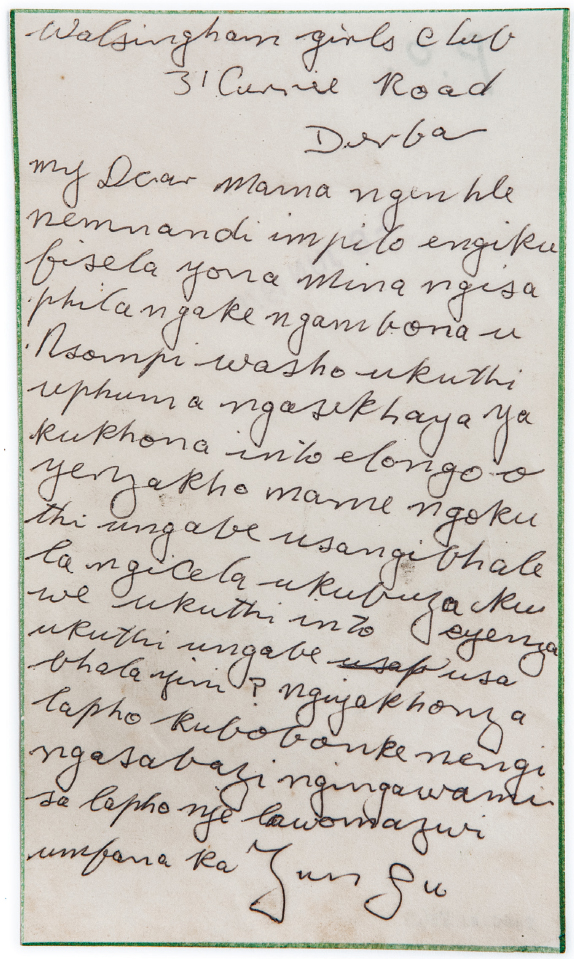

Zungu himself, in the only letter in the archive written by him, inscribed to ‘My dear Mama’, writes in 1970: ‘... there is something that worries me mother why are you not writing I would like to know why are you not writing? Give my regards to everyone at home including those I no longer remember my words end here’ (2000.01.33C). In his heart-wrenching plea, the echoes of the son desperate for news from home reverberate still, more than 40 years later, even in the electronic age of instant communication. The letter is written on a non-standard-size piece of paper and meticulously edged in green felt-tip pen (2000.01.33C, Figure 13.4). It was contained in an envelope embellished with a ten-point star (or ten-petalled flower) drawn in the top left corner (2000.01.33A). The envelope is otherwise unadorned, except for the address in the bottom left corner, also printed in purple ink from a rubber stamp, below the words ‘Mr Zungu’, which are handwritten in purple letters. Included was a second letter, from Geja Mvelase, who says: ‘I have heard she is not replying your letters I will go and check her’ (2000.01.33B). One of the last letters in the collection is from Jo Thorpe and was written in 1974. She asks Zungu to ‘Please come to my office, because your cheque has arrived it is from overseas’ (2000.01.44B).

Figure 13.4

Tito Zungu

1970

Ballpoint pen, felt-tip pen, paper

14 × 8 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

Many correspondents were not literate and would rely on someone with the necessary skills to be able to communicate. Letters would be dictated to a scribe and their recipients would have to locate someone to read the letter to them. The frustrations of relying on a scribe are clearly articulated in the Zungu letters, as in these excerpts from two letters written in 1968 by Nkanimangele Mhlongo: ‘... forgive me for taking too long replying your letter mother is very sick and also I could not find anyone to write for me yesterday the whole day I was in and out looking for someone but I did not find anyone’ (2000.01.02A, Figure 13.5) and ‘... do not be sickened that I took long to reply the reason is that the person who has been writing letters for me has been sick with flu’ (2000.01.22B, C). The envelope for the first letter has a transistor radio and leaf drawn across its face and the latter has an envelope with two aeroplanes and the text ‘Do try not to be late PIA almost never is’ (2000.01.22A).

Zungu, too, was not literate, although some records indicate that he was taught the basics by the Dominican sisters in 1970 when he started working at Walsingham Girls’ Hostel.17 In his statement published in ADA in 1986, the artist says that he cannot read or write: ‘I had often studied writing and longed to be able to write, with the result that I often practised. Being left handed, the letters turned out back to front. The desire to write soon left me and I found making pictures more interesting …’.18

The correspondents would rely on local stores to receive and keep their mail until it was collected. Zungu’s correspondents wrote most often from the post office box numbers of Ntwashini Store in Stanger, but also Mill Store in Pinetown; Jadoo 8 Fresh Produce in Stanger; Ndulinde Store, Ndulinde; Dewons’ Jerooms (or Tiroom) in Stanger; Thuma Trading Store in Kranskop; Tshelabantu BC School in Doringkop and Nsungwini BC School in Stanger. Their letters are addressed to Zungu at Mill Trading Store, Pinetown; Irvington Dairy, Marianhill and Walsingham Girls’ Club in Durban. The sole letter from Zungu amongst this collection is written from this last address.

Zungu’s envelopes were available for purchase. He also gave decorated and self-addressed envelopes to those he wished to write to him. The letters record the high esteem in which the decorated envelopes were held. Robert’s (surname unknown) letter of 1969, placing an order for some of Zungu’s envelopes, is in an unadorned envelope:

... make others for 6 cents they must be 15 and also make 15 for 10 cents. And those ones for 4 cents. Listen now they do not want the stamp on them, they say you must not stamp them, make others and these ones should be the same as the first ones. Make them quickly please Zungu (2000.01.32B).

Geja Mvelase writes in 1970:

... you also promised that you will make the envelopes for me have you not forgotten to make them please make those for me I am not going to forget that you have to do them for me brother I will pay you, the one that you sent your letter with is very beautiful I would like to have the same as that one, I cannot wait for it I want to show off (2000.01.33B).

Figure 13.5

Tito Zungu

1973

Ballpoint pen, felt-tip pen, rubber stamps, pencil on envelope

6.2 × 10.9 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

The Zungu archive reflects the numerous solicitations for assistance and obligations of financial support for those back home that are a marker of the urban employed in a context of rural poverty. An unsigned 1966 letter in an envelope with an aeroplane across the top left corner (2000.01.06A) pleads: ‘I got the money on the 8 Monday – please find me a job in that place – do not forget’ (2000.01.06C) and Zungu’s brother (HW Mehlomane Zungu – Willie) writes in 1967, also in an envelope with an aeroplane across the face, ‘... I am looking for a job there – there is no money’ (2000.01.16), while his brother-in-law, Muntu Shandu, writes in 1969 ‘... I am asking you to look for me a job help me I am struggling ... tell me when you find one I will be happy’ (2000.01.31B). This last letter is in an envelope with a crude sketch of a house on it that does not appear to be drawn by Zungu (2000.01.31A).

Saraphina Dube writes to Zungu, her brother-in-law, in 1966 with an extensive list of her requirements which are quoted here in full:

I am letting you know that the money is eight pounds the items are my father’s shirt and waistcoat and a hat my mother’s items are traditional mat a head-scarf a pillow ... and a towel a dish washing soap … two handkerchiefs two shirts for my brother … and a blouse for Bhubhu two towels two white and two red and four t-shirts and four vests ... and four small kerchiefs two of them must be white and other two must striped and six facecloths and four dozens and six packets of sugar and a knife (2000.01.09B).

This letter is contained in an envelope that has rudimentary ballpoint-pen drawings of plant forms on the front; it is not clear if this was the beginnings of a Zungu drawing or, as seems more likely considering the difference in style, is perhaps by another hand.

Shiyabenkani Mhlongo berates Zungu in 1967 for his lack of financial support:

... we are not feeling well at all I have toothache what is more painful is the fact that I do not have even fifty cents to take it out while I have many sons people are mocking me … when I got the letter I was happy what is bad is that you did not send me even one rand … that is all I want to tell you that I am struggling to make ends meet (2000.01.14B).

This letter is in an envelope with an aeroplane diagonally across the left side (2000.01.14A). Mrs P Gumede in 1974 is grateful for her support ‘... I got a letter with R2 thank you my child and may God be with you I bought tea and beans I thank you very much’ (2000.01.42B). Her envelope is unadorned (2000.01.42A).

Some of the letters reflect the indignities and hardship of life under apartheid. Zungu’s brother writes in 1966:

Do not forget that I will not receive my mail if you use the names that are not in my dompas – whites are going to refuse – use Willie E Zungu or Mehlomane Zungu because they are going to say I am thief who wants to steal the money – because it is not mine – by mentioning the name that does not exist in the dompas … I will thank you after sending me R4 (2000.01.05B).

An unsigned letter, also from 1966 and addressed to ‘Dear my brother’, wonders ‘what was question of that white person the one who asked whether you were educated or not – what was he thinking’ (2000.01.06B). The stamps on the envelopes alone tell a South African history of exclusion through the choice of political and cultural events considered worthy of commemoration: Cape wine estate Groot Constantia (1961); the lives of South African prime ministers DF Malan (1974) and Hendrik Verwoerd (1966); the fifth anniversary of the Republic of South Africa (1966); the world’s first heart transplant (1967); the SA Games (1969); the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) mail coach (c.1969); various agricultural sectors including a sheep (1972); the centenary of the University of South Africa (Unisa) (1973); the 25th anniversary of the Voortrekker Monument (1974) and the gold mining industry (1974). The value of a postage stamp for standard-size local mail increased from 2½ cents in 1961 to 4 cents in 1974.

Figure 13.6

Tito Zungu

1969

Ballpoint pen, pencil on envelope

8.9 × 15 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

The advantages of earning in an urban situation can be heard in the admiration and envy of Zungu’s brother, M Wilson Zungu, who enquires in 1968, from Stanger, of Zungu in Pinetown: ‘Now my brother I would like you to tell me about the girls – how are they going to be – will there be many of them – I want to know my brother’ (2000.01.24B). This envelope has two aeroplanes and the year 1968 drawn down the left side (2000.01.24A). Fifteen of Zungu’s letters are love letters, written in evocative, poetic language that describes the longing and frustration of a couple who are parted. In two letters from 1967, Ngethusile Mhlongo, whom Zungu married in 1978 after more than a decade of courtship, yearns: ‘… sometimes when I am thinking of you I feel like I am next to you but when I think about our situation it is then I realise that you are not here at all, I am missing you my love’ (2000.01.12B) and: ‘Oh go my piece of paper and give my regards to my love the mountains that see you for me must be satisfied indeed mountain mountain I do not have many words’ (2000.01.15B). Both letters are in envelopes that have extensive drawings, the first with trees and houses (2000.01.12A) and the second with a large aeroplane across the bottom (2000.01.15A). The archive also includes love letters from Nkanimangele Mhlongo, such as this from 1968: ‘I am missing you very much my darling but now I am happy … my “dudu” of the heart the day you come I will need the wings’ (2000.01.22B) in an envelope with an aeroplane across the front. (2000.01.22A). There are letters also from Hlekabenqaba Mhlongo, who writes in 1969: ‘I even ask myself whether you “poisoned” me in order to love you that much, I sometimes say to myself the plate and spoon you use for eating must be satisfied. Oh go my paper and give my regards to my love’ (2000.01.30B). This last is contained in an extensively embellished envelope with a large aeroplane across the face (2000.01.30A, Figure 13.6).

The temptation to speculate as to the relationship between the three Mhlongos who author the love letters, Ngethusile, Nkanimangele and Hlekabenqaba, is irresistible. Were they sisters vying for the hand of the same man? Or are they three names for the same person? The letters from Ngethusile and Hlekabenqaba both have the same address, Jadoo Fresh Produce, while Nkanimangele’s does not include a sender’s address. What is irrefutable though is the significant difficulty inevitably faced by those conducting a long-distance relationship.

Although we do not know how long each envelope took Zungu to complete (and obviously the amount of time would depend on the complexity of the drawings), it is clear from their precision, density, focus and delicacy that these represent considerable investments of work in the creation of the vehicle of communication: true labours of love. As a comparative measure, a (much larger) drawing took about a month of working at night.19 Colin Richards describes the lengthy preparations that Zungu required in order to feel able to undertake his drawings: ‘He insists that he cannot simply begin drawing anywhere, anytime. His “method” is itself an initiation and a meditation … he will not get too excited, nor will he become bored. Too much of either will destroy the very sense and rhythm of the act.’20

The images of aeroplanes on the envelopes have become synonymous with Zungu’s art. The combination of symbolic and practical functions is described by Andries Botha as ‘the metaphor of the envelope, its shape, its function as carrier of both intimate and pragmatic information thus becomes a metaphor of Zungu’s preoccupation with the idea of flight and distance’.21 Zungu stated that he received divine inspiration to draw an aeroplane without ever having seen one: ‘My first jet plane was drawn from pure inspiration, because I only saw an aeroplane or picture of one after I had drawn it ... I am sure that my talent is a gift from God.’22 The symbolic value of aeroplanes as images of modernity, speed, aspiration and technology is very apt on envelopes as the vehicle of communication that is physically carrying the messages, something similar to the airmail sticker that is used to distinguish between postal services that travel by land or by air. Zungu’s first flight is recorded as taking place in 1987 when he travelled with Ngethusile, his wife, and Jo Thorpe to Johannesburg for his second solo exhibition,23 although Yvonne Winters indicates that this occurred much earlier, in the 1970s.24 Zungu certainly flew on other occasions. Botha describes the artist’s fascination with the in-flight view of their aeroplane when he and Zungu flew to Amsterdam together in 1993: ‘He kept coming to fetch me to show me the small little aircraft captured on his video screen in front of his seat, indicating to me how wonderful God actually was.’25

The symbolism of the correspondence is not restricted to the imagery in the drawings. Ngethusile Mhlongo writes in 1967 of her distress at receiving a letter from Tito Zungu that was written in red ink:

I heard the news that you were sick and that you went to hospital you were seriously injured just because of Christmas accidents this is bad luck … you made me anxious you wrote to me in red ink it is not right the red ink signals danger or death (2000.01.18B).

‘I always wish you a good health I am still well but not much’

The Zungu archive at WAM contains correspondence that articulates many of the conditions central to the experience of migrant labourers in South Africa during apartheid: rural poverty, illiteracy, lack of education, long-distance relationships, family ties, cultural values, the dependence on the postal system. All are embodied in the personal letters sent to the artist and the powerful visual symbol of aeroplanes he drew on the envelopes. Together they clearly demonstrate the value the artist placed on keeping close to his heart his loved ones who were far away.

The narrative of migrancy in South Africa is articulated in broad brushstrokes commensurate with the expanse of time and people affected. In the mass of information, though, it can be difficult to hear the voice of individual experience. This opportunity is clearly afforded by the Zungu archive at WAM: a body of texts that was created in the private register, enclosed in containers that traversed the space between the private and the public sphere, but remained essentially in the personal register and, on acquisition by the museum, has entered the public domain.

Notes

1. The numbers in brackets refer to the relevant museum accession numbers of the envelopes or letters referred to in the text.

2. Zungu’s inclusion in art exhibitions started in 1971 and he sold his first drawing to Durban Art Gallery in 1974.

3. Group exhibitions in Durban: ‘Art-South Africa-Today’ at Durban Art Gallery in 1971, 1973 and 1975 and ‘Things People Make’, also at Durban Art Gallery in 1981. More than 60 envelopes: according to Pancho Gueddes, in A Gueddes, ‘Mr Tito Zungu: Master of the Decorated Envelope’, ADA: Architecture Design Art 2 (1986), 19.

4. Publications on Zungu include the retrospective catalogue produced in 1997 by the Durban Art Gallery; substantial entries in the 1986 and 1994 ADA magazines, G Younge’s Art of the South African Township (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988) and J Thorpe’s It’s Never Too Early: African Art and Craft in KwaZulu-Natal 1960–1990 (Durban: Indicator Press, Centre for Social and Development Studies, University of Natal, 1994). He is also in survey publications, including R Burnett’s Tributaries: A View of Contemporary South African Art (Johannesburg: IM Selbstverl. der Abteilung Kommunikation, BMW, 1985); S Sack’s The Neglected Tradition: Towards a New History of South African Art (1930–1988) (Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery, 1988) and S Williamson’s Resistance Art in South Africa (Cape Town: David Philip, 1989).

5. J Addleson and P Khoza, ‘Biography’, in Mr Tito Zungu: A Retrospective Exhibition (Durban: Durban Art Gallery, 1997), not paginated; Sack, Neglected Tradition, 134.

6. T Zungu, ‘Mr Tito Zungu’, ADA 2 (1986), 22.

7. Gueddes, ‘Master’, 19.

8. G Younge, ‘Postcards from the Kitchen’, ADA 2 (1986), 22.

9. Zungu, ‘Mr Tito Zungu’, 22. According to the South African Reserve Bank website, South Africa used the British currency of pounds, shillings and pence until 1961 when the new currency of rands and cents was introduced (http://www.resbank.co.za).

10. Addleson and Khoza, ‘Biography’.

11. Zungu, ‘Mr Tito Zungu’, 22.

12. Addleson and Khoza, ‘Biography’.

13. C Brown, ‘Zungu, Tito’, ADA 12 (1994), 123.

14. Zungu is quoted as saying: ‘From Mapumulo we could see the ships on the sea, and I desired to have a close-up view of them so I could draw one’ (Zungu, ‘Mr Tito Zungu’, 22).

15. S Williamson, South African Art Now (New York: Collins Design, 2009), 74.

16. See http://www.luthulimuseum.org.za.

17. Addleson and Khoza, ‘Biography’.

18. Zungu, ‘Mr Tito Zungu’, 22.

19. Addleson and Khoza, ‘Biography’.

20. C Richards, ‘Mr Tito Zungu’s Art of the Middle Smile’, in Mr Tito Zungu: A Retrospective Exhibition (Durban: Durban Art Gallery, 1997), not paginated.

21. A Botha, ‘Tito Zungu’, Revisions: Expanding the Narrative of South African Art, available at http://www.revisions.co.za/biographies/tito-zungu/.

22. Zungu, ‘Mr Tito Zungu’, 22.

23. Addleson and Khoza, ‘Biography’.

24. Y Winters, ‘Indigenous Aesthetics and Narratives in the Works of Black South African Artists in Local Art Museums’, MA thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 2009, 147. Available at http://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/jspui/bitstream/10413/618/3/Winters_Yvonne_2009.pdf.

25. Botha, ‘Tito Zungu’.