During the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century, black women in the rural areas of South Africa were largely subject to the authority and control of their male relatives: fathers, brothers, husbands and sons.1 They bore children for their husbands’ lineages, did most of the gardening and crop production, cooked and raised children till they were old enough to be initiated as men and women, or join adult age grade regiments. Under this system, there was a clear separation of labour – men worked with iron, carved wood, hunted and prepared animal skins for making clothing. Thus sewing was generally associated with men before the advent of European settlers, traders and missionaries brought cloth, metal needles, cotton thread and, most notably, beads into the rural context. Missionaries introduced sewing classes for women, who became the main producers of cloth dress and beadwork in a very short time. By 1850, beadwork was established as a female occupation/craft/art among black peoples on the east coast of South Africa, a praxis that spread inland with the beads.

Ironically, many writers have presented the production and wearing of beadwork as ‘traditional’ among many southern African black communities, but researchers have shown that beadwork, on the scale that emerged in the nineteenth century, was only possible with the provision of the necessary materials by Western traders. Southern African beadwork was thus an invented indigenous tradition and was not of any great age.2 The use of small glass beads to make intricate beaded items (as opposed to simple strings of beads) started at the end of the eighteenth century, but there was a much greater florescence of complex forms in the latter part of nineteenth century. From around 1840, women invented or adapted techniques that allowed them to develop new forms, possibly in response to the disruptions in traditional social orders that followed the introduction of a cash economy. These included men’s recruitment into migrant labour and the resultant pressure on women to uphold tradition and were reflected in the ‘traditional’ objects that they made. These forms were new, but they quickly became ‘traditional’ and were treated as markers of ‘tradition’ by the people who made and wore them.

Women and shifting social structures of migrant labour

The greatest threat to the traditionalist patriarchal structures outlined above came with the colonial imposition of hut taxes (and later poll taxes) on rural dwellers and the resultant movement of men recruited for work, first on the mines and later also in industry and commerce.3 The vast majority of African women were left behind, at home, to tend the fields, bring up children, care for the elderly and, importantly, to keep cultural identity alive through the observance of customs sanctioned by the ancestors.4 From the early nineteenth century onwards, missionaries intervened in social arrangements so that some women (albeit relatively few) left the traditional village or homestead for education in Western skills, the most common of which was sewing: some entered domestic work in colonial towns and a few became teachers, nurses or nuns and thus migrant workers themselves.5

The women of the male migrant labourers’ families took over men’s roles at home, in some cases, ploughing and working with cattle in ways that were not sanctioned ancestrally.6 As was the case for all African peoples in southern Africa, married women lived with their husbands’ families; they were under the control of the men of their husbands’ families and had to follow the lead of their mothers-in-law.7 Unmarried women were subject to the same structures of authority in their fathers’ homesteads. Both married and unmarried women were important in maintaining links to the past, to custom and to home and in the production and sustenance of future generations. The absent male migrant labourers earned cash, to provide bride-wealth payments in order to establish their own families at home, or to help already established rural families. Their wages were also used to purchase trade goods in cities and at trading stores. These were taken back to rural settlements and thus saw to the transformation and sometimes the complete reinvention of local traditions of making, wearing and using material objects.

The trade in beads and the making of ‘tribal’ dress

The introduction of increasingly large quantities of glass beads into southern Africa from the early nineteenth century onwards, via the Cape, Delagoa Bay and then Port Natal, was part of a larger process whereby imported objects were used to complement old forms of dress or invent new ones. This process is recorded in accounts written by traders, missionaries and colonial officials of the indigenous dress practices of southern African peoples. These records, paired with photographs of people wearing beadwork items, as well as the objects themselves, offer an archive that traverses the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Glass beads were, from the start of the trade, highly valued by many African peoples.8 In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, white traders and missionaries exchanged beads for ivory and other exotica.9 The establishment of trade fairs in the frontier regions of the Eastern Cape encouraged barter and increased the volumes of materials exchanged.10

From their first entry into local African communities, beads were a luxury, controlled in distribution within the Zulu kingdom, in particular, during the ascendancy of Shaka and used as currency among isiXhosa-speakers until the collapse of their value by 1831.11 While in the late nineteenth century at the trading stores set up in ‘the bush’ and at concession stores in mining centres from the 1860s onwards, beads were most regularly bought with cash, rather than bartered for exotica, they remained expensive relative to migrant workers’ wages.12

Thus the cash economy, of which migrant labour formed an important part, can be argued to have been an important condition for the extraordinary growth of beadwork in the latter part of the nineteenth century along the eastern seaboard of southern Africa and, only slightly later, in the interior. A complex network of exchange was established, leading from the men earning cash resources by labouring on the mines through to the exchange of cash for beads, thread and other beadwork prerequisites, their removal to the rural districts, where women transformed the beads into desirable items of wear, either for themselves or for someone related to them, or with whom they wished to have a close relationship. The process, however, did not end in the making or even in the initial wearing and display of these masterpieces of women’s work: items were passed down from one generation to another, were unravelled and restrung or have survived as heritage items or as artworks in museums.

Beadwork and ‘traditional’ clothing

Over the course of 150 years, women at home developed beadwork in rural villages and at kings’ courts to fulfil a number of functions, particularly in dressing the body. Early illustrations of beadwork from the Zulu kingdom and Natal give some idea of how quickly women adopted this new medium for embellishing items of dress worn by both men and women.13 Beadwork was also, from very early on, made for sale to white outsiders: photographers in Durban and Cape Town used pieces as props to clothe indigenous subjects in colonial ethnographic portraiture; others collected beadwork for the great colonial exhibitions and ultimately for museums in the heart of colonial power.14 In the process, the makers and wearers of the beaded items, followed and abetted by photographers and collectors, constructed beadwork as ‘traditional’ indigenous dress. These forms of dress garnered specific significance over time, forming ‘traditions’ within the lives of migrants and their families that remained behind in the ‘homelands’.

Beadwork items, such as those worn by many individuals in hundreds of nineteenth-century photographs, were not only intended by their makers or wearers to cover body parts, but also to celebrate and emphasise them.15 Until approximately 1900, in most indigenous southern African communities, only some body parts were hidden from view entirely by covers made of animal hides and/or imported cloth and these were trimmed with glass beads, metal buttons or studs and chain. As these items had, before the arrival of glass beads, been embellished with eggshell or other natural materials, their replacement by large numbers of white and coloured glass beads must have stood out: the number of beads used increased with the importance/ wealth of the individual who wore the beadwork, elevating their visibility amongst their fellows.

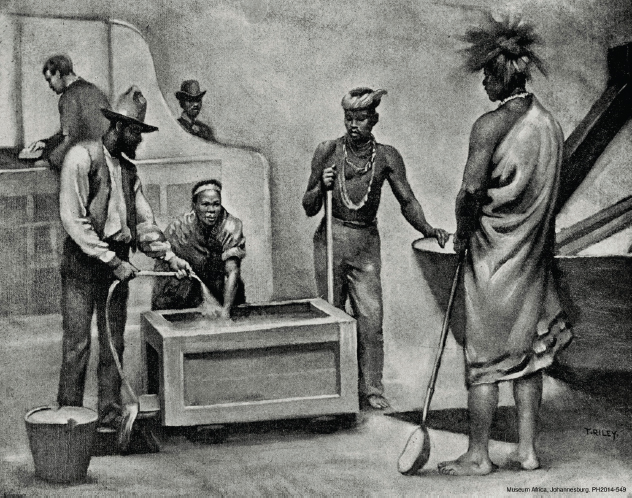

Figure 6.1

Thomas Riley

Diamond washing, from Frank Cundall’s Reminiscences of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition

1886

Engraving

Courtesy of Museum Africa, Johannesburg

Wearing beadwork as clothing was limited to the rural areas from quite early on in the colonial period because rules governing dress in colonial towns in South Africa required ‘proper’ attire. Anyone entering town had to wear clothing that covered the body from shoulder to knee and traditional forms of dress did not, for the most part, comply with such requirements.16 As a result, uniforms prescribed for those who worked as domestic servants in the towns and for those who were resident on mission stations or studied or taught in mission schools were always Western. Pieced, tailored clothing, including smocks, dresses, shirts and trousers for those at mission stations were sewn from imported cotton cloth by women resident there, or by young women at institutions, such as the Inanda Seminary for girls, established in 1869.17 This indexed a shift in division of labour from the ‘traditional’ in most indigenous groups where skin garments, such as karosses, the leather skirts (izidwaba) worn by isiZulu-speaking women and the aprons worn by Sesotho-, isiXhosa- or Setswanaspeakers, as well as grass belts, fringed pubic aprons and bangles, had generally been prepared and sewn by men.18

Even the ubiquitous blankets worn by miners ‘captured’ in photographs (which Sandra Klopper casts as a means for Eastern Cape miners to maintain their indigenous identity in the context of resistance to Western dress modes) were generally imported from England.19 Figure 6.1 is an illustration by Thomas Riley, entitled Diamond Washing.20 What is important about this image, for my purposes, is the mixing of modern and supposedly traditional dress in what was already a construction or invented image of a mine scene in an exhibition. Every item worn by the migrant labourers in this etching was made of imported material, but the men are cast as wearing ‘traditional clothing’, part of a display that emphasised European-imposed progress on the supposedly ‘uncivilised’ natives. The beadwork in this image registered an index of the ‘uncivilised’, but it was also silent witness to women’s work with imported, modern materials and part of a constantly changing clothing regime.

Valorisation of beadwork: Women, clothing and ‘tradition’

In the literature on beadwork in southern Africa, the indigenous peoples’ valorisation of beadwork as a form of ‘traditional’ praxis is simply assumed as historically founded and remains uninterrogated. Beadwork is not placed within a wider context of historical change and shifting roles. Yet, as Klopper points out, women ‘have played a significant role in constructing and even controlling the world’ that seemed to be controlled by men’s activities.21 The ambivalence in beadwork’s status as traditional is caused not only because it is also a modern phenomenon, but because it was largely developed and vastly expanded by the women left behind in the rural areas, which underwent radical changes with migrant labour.22

Beadwork appears to have lodged in the female domain (in southern Africa) from the start. Beads were strung and sewn by women, not only for themselves, but also, importantly, for men, whose absences from the homestead for long periods were to become increasingly common with the growth of migrant labour.23 Beaded dress items were mostly worn for ceremonies that had to be performed at home because the community’s presence and participation was essential to their success. Some items were specifically linked to rites of passage, such as initiation, courtship and marriage, many of which required periods of seclusion, separation and abstinence prior to the principal participants’ reintegration into communities.24 Most tellingly, these ceremonies were performed at home, in the presence and in the domain of the paternal ancestors.25 Migrant labourers’ movements out of the community, and thus out of range of direct ancestral intervention, and then back again, could be argued to have been a rite of passage, which replaced or augmented the transition from boyhood to manhood and marriageable status within the patriclan. These movements required a rite or ceremony of reintegration, in which beadwork played an important part. Young migrant labourers returning from the mines with their wages and material goods courted young women with gifts of beads; they received gifts of beaded items from their admirers in return.

In all these cases, women would have been at the ‘bead face’ of the construction of particular visual identities: both men and women used the beadwork ostentatiously for important public occasions.26 Beadwork thus accrued value, as it was hoarded/ collected, particularly by married isiXhosa-speaking men, although innumerable photographs of people from diverse ethnic groups show that similar practices obtained among other groups.27

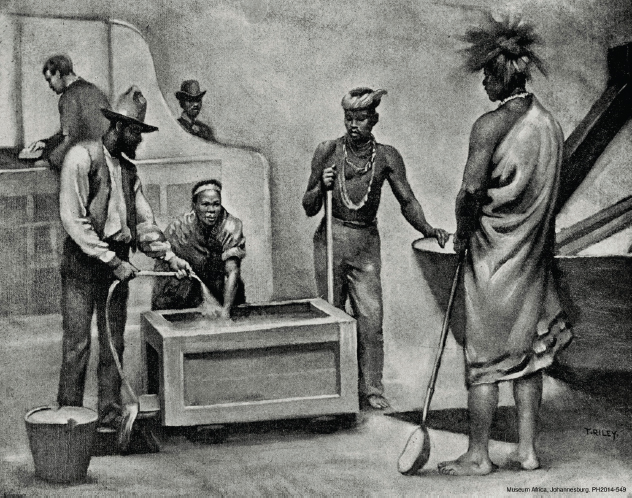

Figure 6.2

Photographer unrecorded

Mine police boys

c1909

Postcard, J Barnett & Co

Courtesy of Museum Africa, Johannesburg

The fact that the making and wearing of beadwork functioned as an index of ‘ethnic’ identity, largely in the period of white settlement and the growth of urban styles of life among black people, is significant in the construction of beadwork as a black ‘tradition’. While beadwork was in some ways to be built to white settlers’ and tourists’ expectations of seeing a spectacle when they encountered the ‘savage native’ in South Africa and his or her ‘tribal’ status, it was also actively used as an expression of ethnic belonging and difference (at the level of more localised groups such as Mpondo and Gcaleka, rather than Xhosa) by black traditionalists.28 Vincent Zanoxolo Gitywa suggests: ‘ Although beads and beadwork are originally foreign elements in Xhosa culture, it has become so accepted and adapted that beadwork is today universally accepted as a traditional craft not only of the Xhosa, but also of all the Bantu in South Africa.’29

Southern African beadwork thus encompasses many different visual styles developed at different times and in a variety of locations: beadwork itself is mobile and could travel from one district to another. Nevertheless, as Gitywa suggests, beadwork could, in particular periods, act as a marker of its wearer’s ethnic group and place of residence/birth. While traditionalists followed particular body practices that marked them physically and permanently as women, men or members of a specific ‘ethnic’ group, once they were stripped of ‘customary dress’ and placed in ubiquitous Western style clothing – in the case of migrants, this would be trousers and shirts, sometimes with shoes and socks or, indeed, in plain blankets – they would lose their immediately striking, particular visual identity. ‘Civilised’, non-traditional native dress is seen, for example in a photograph (Figure 6.2) of two mine policemen, which shows them dressed in knee-length breeches, dark jackets, jauntily angled pill-box hats and carrying knobkerries, one a staff with a peculiar top. Each wears a leather bandolier belt buckled diagonally across the torso. The multiple holes in these belts may well have been made to attach loops for cartridges, but here are left empty because they are not armed with guns.

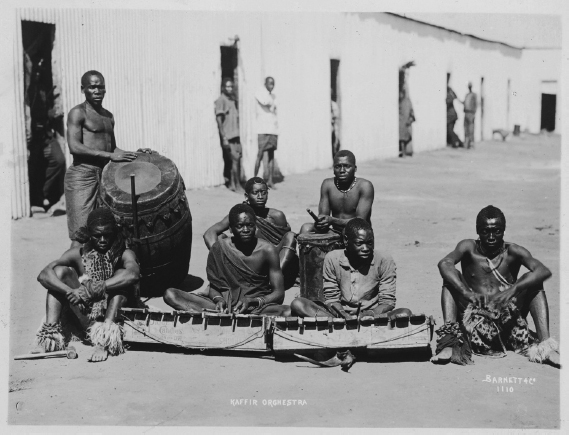

The migrant labourers on the mines, mine policemen, men in domestic service, as well as in other jobs, such as laundry entrepreneurs in Johannesburg, were often denuded of their ‘traditional’ costume.30 We need to understand the process of migratory labour as one in which visible difference between labourers was eradicated, except in the context of the mine dances where ethnicity was spectacularly on display, as in the case of the photograph of Chopi musicians in Figure 6.3, or stickfighting in Figure 6.4, whose exotic dress is largely an invention.31 The rural background is the place from which visual and visible difference was, and perhaps still is, maintained and promoted through a form of (beaded) excess.

Figure 6.3

Joseph and David Barnett

Chopi musicians

Date unrecorded

Postcard, silver gelatin print

Barnett Collection, courtesy of The Star archives, Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

The beaded belts, necklaces, panels, fringes, aprons, leggings, armbands, waistcoats and other items of dress that feature in images of southern African peoples from the mid-nineteenth century onwards were all responses of excess, particularly in the sheer number of beads used and their increasingly complex colours and patterns. This is recorded as happening from the late nineteenth century onwards in men’s dress among isiXhosa- and isiZulu-speakers, but was also evident in women’s attire there and elsewhere.32

However, the ‘tradition’ to which the abundant finery worn at home belonged was in a constant process of invention and reinvention, starting from the point at which indigenous clothing, formerly made of plant fibres or animal skins, was adorned with imported glass beads. The beading techniques were varied, labour intensive and time consuming. They required concentration and an ability to envisage patterns that were only revealed in a completed ‘garment’ because beaders worked without patterns. The beaders not only made use of imported beads, thread and needles to transform traditional forms, they also possibly borrowed designs from other sources.33 Beads were often used to transform manufactured items brought by migrant labourers in an elaborate process. Some beaded items incorporated discarded Western industrial detritus in completely new interpretations of the commonplace. Beaders thus created new kinds of objects that reflected particular kinds of interactions by individuals with changing circumstances, as well as the building of forms of resistance and cultural survival.

Figure 6.4

Photographer unrecorded

Natives in a mining compound

1900–1901

Postcard, silver gelatin print

Courtesy of Museum Africa, Johannesburg

Leather and beads: Mix and match

An example of how beaded items made by women became incorporated into migrant workers’ home dress is seen in a photograph dating from the 1890s, possibly taken on the outskirts of Pietermaritzburg’s Zwartskop location (Figure 6.5).34 A group of five, presumably isiZulu-speaking, young men, in the prime of life, stand posed against a background of trees, cacti and aloes, on a piece of ground with patches of grass that locate it outside the studio. Yet these men have all clearly been selected, probably on account of their physical beauty, their lean bodies on display to the prurient Western gaze.

They are ‘dressed’ in attire appropriate for rural homes, not for cities or mines, which is generally classed as ‘traditional’. Collections of animal tails cover their pubic areas, held by girdles of string or skin and pendant bead strings that would enhance the kinetic effect as the wearer moved. All wear beaded necklaces around their necks, following patterns by then established as common and thus also considered ‘traditional’. So-called ‘love-letter’ panels feature on many of these and on the strings of beads worn bandolier-style over one shoulder and around the torso. Young women made these beaded items as gifts for their courtiers and men took great pride in sporting this finery.35 Three men on the left of the image have rather jauntily positioned beaded straps as headdresses; the man second from the right has a headband of strings of beads around his head, with more hanging down on either side; only the man on the far right has no headgear and a minimum of beads.

Mixed into this attire, however, are some anomalous elements, such as the bandolier-style straps of leather worn by the man on the far left and the three belts buckled around the upper torso of the man on the right. Each of the three men on the right wears a single leather belt left plain; two men wear belts in different styles, one of multiple tubes, the other of plaited grass, all covered in beads and the latter with brass studs. Most of the leather belts have buckles – probably acquired whole or in parts from trading stores. In all cases, however, the imported belts are worn as items whose utility is no longer an issue – they do not hold up trousers, they are worn against the bare skin, some at the waist, but others strap the body as did ‘traditional’ beaded items. The leather belts bind their wearers’ torsos like bedding rolls and some look like those used for such purposes. Their presence on these bodies indexes an extrusion of those bodies into other contexts and, on their return to their homes, an intrusion of the outside world into the home environment. Their presence is mediated by the traditional beadwork and miniaturised shields.

Figure 6.5

Photographer unrecorded

Zulu warriors

Date unrecorded

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy of Museum Africa, Johannesburg

In the early days of beadworking, women made panels using various techniques. Among these were ankle straps worn by men and women from the 1860s onwards, enhancing the visibility of the wearer’s movements.36 But these were easily replaced in the migrant labourer’s dress repertoire. Two men at the centre and the one at the right of Figure 6.5 have wrapped around their lower legs the legging part of boots, removed from the shoe part so that they are barefoot. Attached are metal chains – one with discs. In their functional and pristine state, boots would have been wildly expensive, but their surviving parts have been reused here to replace beaded anklets. Absorbed into a tradition of wear for unmarried men, such items marked their wearers more immediately as people who interacted with the modern machinery of commerce, compared with those whose connection to home and tradition was marked by beaded items alone. In the photograph, the boot leggings stand in contrast to both the beaded items made by women and the shields and sticks that would, if they were the right, larger, size (small shields were used by men for blocking blows in stick fights and for marriage ceremonies by brides), have marked these men as warriors for both ‘natives’ and ‘settlers’.37 Thus, although we cannot definitively say that these men were migrant labourers, they are of an age at which they could have been and they have accumulated around their bodies markers of migrant identity alongside the ‘traditional’ forms of beaded finery.

Xhosa integrations of leather and beads

Western items, such as gaskets from boilers that were beaded, decorated with woollen pom-poms and worn as collars, beaded sunglasses, tennis-racquet frames, bottles and many others, moved into the rural areas of the Eastern Cape in the baggage of returning migrant workers to be transformed into new and extraordinary objects by women beadworkers.38 Leather straps were particularly favoured by mid-twentieth-century Gcaleka artists for making belts, as is reflected in the multiple straps with beaded trim along their edges worn wrapped around torsos by both women and men in the late 1960s, seen in photographs by Alice Mertens.39 These leather strips were, however, also used to make the framework for more complex garments.

A (female) master beader constructed a vest/ waistcoat (Figure 6.6) by connecting panels of largely white beads with geometric motifs in primary colours to tan coloured leather straps, thus providing both chest and back pieces and longer side sections between the strips. The side panels are placed with gaps between them, allowing the viewer to see the skin of the wearer and only partially masking the body. The surface of the tan leather straps is punctuated by regular holes (probably machine made), but these were filled in places by rows of plastic imitations of the mother-of-pearl buttons favoured by isiXhosa-speakers since they first encountered them on European clothing. They, too, have come to be regarded ‘traditional’, but were used in excess on many items, functioning as ornaments not fasteners, their whiteness and shine referencing ancestral presence and general coolness, but also acting as indices of modernity.

Figure 6.6

Artist unrecorded,

Xhosa, Eastern Cape

Ivethiboyi (vest)

Date unrecorded

Beads, buttons, leather belts

91 × 50 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

Figure 6.7

Artist unrecorded

Xhosa, Eastern Cape

Man’s waistcoat

Date unrecorded

Beads, leather, buttons, metal hooks and eyes

61 × 39 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

A similar, possibly Mpondo style is visible in the pink and blue waistcoats illustrated by Dawn Costello as part of a married man’s wear and eulogised by David Bunn as being particularly attuned to wear over brown skins.40

These also use leather strips (in these cases, locally produced) on the edges, which fastened and some were also elaborated with multiple mother-of-pearl buttons. One of the names given to such vests was an umwayo, which, according to Costello, suggests a large number of beads, pointing to a local understanding of the excess that such items represented.41 A waistcoat such as this represented a considerable investment of resources by the person who bought the materials and the women who produced the finished item. But, and possibly more importantly, it would have marked its wearer as a participant in a process of speaking back to the centre of power, as an African version of a modern item of clothing.

Hybridity and modernity through beadwork

The beadwork made by those left behind in the rural areas, worn by them and by the migrant workers at home or at mine dances, both the subjects of colonial photography in the late nineteenth century and more so in the twentieth century, can be followed as a trajectory to the eventual resurgence of beaded wear as identity markers in urban township celebrations. In all these contexts, it can be argued that beadwork constitutes spectacular forms of visual classification and display. Beadwork was about the production of difference, between African insiders and settler outsiders, as much as between different African indigenous cultures. It replicated rigidified lines of division, marked on bodies and in spatial divisions of people in mine hostels, townships, education and everywhere else. It is also represented thus in much of the coffee-table photography of the twentieth century. But it also combined tradition and modernity in ways that denied there is or was ever a clear separation between the two. It was thus always hybrid.

Figure 6.8

Artist unrecorded

Zulu, KwaZulu-Natal

intolibhantshi (waistcoat)

Date unrecorded

Beads, textile, buttons

50 × 46 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

Beadwork and bodies of resistance

Beadwork and other African transformations of imported materials were also forms of resistance to the ‘primitive’ paradigm, to the missionary need to make converts conform to their ways and they enabled the creation of modern forms of indigeneity. Beadwork was most often displayed on an otherwise almost naked body, as seen in Figure 6.5 earlier, a body that was inadmissible in the spaces of the urban, of the mission, of the ‘civilised’. This ‘traditional’ body was also rejected by the African intellectual elite that emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, the isiZulu-speaking amakholwa and the isiXhosa-speaking converts to Christianity, the amagqobhoka, who chose to dress in suits and ties, in Western dresses, skirts and blouses.

However, such oppositions are also misleading because many Africans were able to reconcile aspects of both traditions, to develop a hybrid body that utterly confounded this kind of prescriptive acceptance or rejection of invasive elements. In some instances, this resulted in invented forms of indigenous clothing, such as the entirely beaded vests and waist pieces made by isiXhosa-speakers, discussed above. In other cases, the mix was more directly visible, as where isiZuluspeaking makers of beaded jackets and waistcoats used (or copied) store-bought, Western dress items as the base for the application of beaded strips and panels, reflecting designs common in Nongoma, Hlabisa and the Ngwane areas around Underberg in the 1950s and 1960s. These waistcoats and jackets (Figure 6.8) were largely worn in the contexts of the rural home, in combination with other Western dress items.42

A similar hybridity and defiance is seen in the painting by Sibusiso Duma, Inyanga nomthagathi (Figure 6.9). Here, the migrant healer, moving from the countryside (implicitly) to the city, wears a Westerstyle green jacket, pants, prominent and shiny leather shoes and carries two leather suitcases. But on top of the jacket, he wears two floral, possibly beaded bandoliers, large earlobe plugs and has a fly whisk with a beaded handle tucked under his right arm. These items mark him as a traditionalist because they link him to the dress worn in rural areas, but it is the horned, grey-haired, dwarf-sized figure (in what looks suspiciously like a graduation gown) accompanying him, that signals his possible ritual and social pollution through engagements outside his home turf. It is clear from this painting that the movement of the migrant across boundaries between home and the distant city, and/or possibly particularly, the mine with its journeys underground, evokes extraordinary ambiguity within local, rurally centred concepts of the world. In the light of this painting, one might suggest that the bandoliers of beadwork contain the danger posed by the adoption of modern dress, crossing over it, reminding the viewer and the wearer of an other, not modern, or differently modern, self. Within the context of the painting, the beadwork protects its wearer and makes his re-entry into the ancestral domain of home possible.

That women were the guardians of belonging, signalled in the form of developing, changing and evolving traditions of beadwork, is significant. The migrant worker left the city and returned home to the place where women’s labour produced and maintained ‘tradition’, in the speaking of language (mother tongue), in the raising of children and the production of food. But the women’s ‘unseen’ labour, their use of time for the production of beadwork was what enabled traditions to be marked visibly on the body and celebrated aesthetically. Such distinctive use of beads in their variety of colours marked identities in ways that had not been necessary before the development of the migrant labour system. The beaded body had become a body of resistance, proclaiming tradition and asserting modernity in the same breath.

Figure 6.9

Sibusiso Duma

Inyanga nomthagathi (Inyanga comes to town)

2011

Acrylic on board

Campbell Collections, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Notes

1. The research for this article was made possible by a grant from the National Research Foundation of South Africa.

2. There is a large literature on southern African beadwork, not all of which acknowledges these basic factors. Examples of those that gloss over the history are: D Costello, Not Only for Its Beauty: Beadwork and Its Cultural Significance Among the Xhosa-Speaking Peoples (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 1990); J Broster, The Tembu: Their Beadwork, Songs and Dances (Cape Town: Purnell, 1976); A Mertens and J Broster, African Elegance (Cape Town: Purnell, 1973); A Mertens and H Schoeman, The Zulu (Cape Town: Purnell, 1975) and P Mayr, ‘The Zulu Kafirs of Natal: V, Clothing and Ornament (continued)’, Anthropos 2.4 (1907), 633–645. More historically nuanced accounts include G van Wyk, ‘Illuminated Signs: Style and Meaning in the Beadwork of Xhosa- and Zulu-Speaking Peoples’, African Arts 36.3 (2003), 12–33, 93–94; S Klopper, ‘From Adornment to Artifact to Art: Historical Perspectives on South-East African Beadwork’, in South East African Beadwork 1850–1910: From Adornment to Artifact to Art, ed. M Stevenson and M Graham-Stewart (Vlaeberg: Fernwood Press, 2000) 9–43; C Kaufmann, ‘The Bead Rush: Development of the Nineteenth-Century Bead Trade from Cape Town to King William’s Town’, in Ezakwantu: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape, ed. E Bedford (Cape Town: South African National Gallery, 1993), 47–55 and A Proctor and S Klopper, ‘Through the Barrel of a Bead: The Personal and the Political in the Beadwork of the Eastern Cape’, in Ezakwantu, ed. E Bedford, 57–65.

3. P Maylam, A History of the African People of South Africa: From the Early Iron Age to the 1970s (Cape Town: David Philip, 1986).

4. Issues of how to understand the position of women in pre-colonial society in Natal are complex and much discussed. A good overview of some of the arguments is given in S Klopper, ‘The Art of Zulu-Speakers in Northern Natal-Zululand: An Investigation of the History of Beadwork, Carving and Dress from Shaka to Inkatha’, PhD dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1992, 146–167.

5. See A Nettleton, ‘To Sit on a Cushion and Sew a Fine Seam: Gendering Embroidery and Appliqué in Africa’, in Material Matters: Appliqués by the Weya Women of Zimbabwe and Needlework by South African Women’s Collectives, ed. B Schmahmann (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2000), 20–38; A Nettleton, ‘In Pursuit of Virtuosity: Gendering “Master” Pieces of 19th Century South African Indigenous Arts’, Visual Studies 27.3 (2012), 221–236; G Callaway, Building for God in Africa (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1936) and J Tyler, Forty Years Among the Zulu (Cape Town: Struik, 1971).

6. Maylam’s History, which addresses the different impacts migrant labour had in different parts of South Africa, barely mentions these aspects.

7. In discussing these contexts as generalisations, there is inevitably some fudging of the issue of whether all southern African groups followed strict agnatic lineage patterns in their living arrangements. See, for example, WD Hammond-Tooke ‘Descent Groups, Chiefdoms and South African Historiography’, Journal of Southern African Studies 11.2 (1985), 305–319 and J Guy, ‘Analysing Pre-Capitalist Societies in Southern Africa’, Journal of Southern African Studies 14.1 (1987), 18–37.

8. The trade in beads in southern Africa dates back to before the advent of European traders on the coast, having occurred between African peoples as recorded by M Shaw and NJ van Warmelo ‘The Material Culture of the Cape Nguni, Part 4: Personal and General’, Annals of the South African Museum 58.4 (1988); J Peires, The House of Phalo: A History of the Xhosa People in the Days of Their Independence (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1981), 97 and J Guy, ‘The Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom’, PhD dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1975. They were traded in small quantities, however, and often made up part of chiefs’ regalia, as was the case of the Venda rulers’ ‘beads of water’; see H Stayt The BaVenda (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931), 26–27.

9. See the account by RG Cumming in A Hunter’s Life in Africa (London: Murray, 1850), 8–16, of his hunting and trading exploits in South Africa from 1843 onwards. He lists the goods he took on his first trip, including ‘three hundred pounds of white, coral, red and bright blue beads of various sizes’, as well as ‘thread, needles and buttons’ – everything one might need for beadwork.

10. C Crais, The Making of the Colonial Order (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 1992) and J Peires, House, 98–103.

11. S Klopper, ‘Art’ and J Peires, House, 102.

12. BH Dicke, The Bush Speaks: Border Life in the Old Transvaal (Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter, 1936); see also Peires, House.

13. Klopper, ‘Adornment’. Mayr (‘The Zulu’) distinguished between what he called ‘skin Zulu’ and ‘blanket Zulu’ as a means of separating two putative periods in which isiZulu-speakers either used indigenous elements of clothing (besides beads) or imported cloth. In fact, this distinction is not tenable.

14. The women who accompanied Cetshwayo in his imprisonment in the Castle and at Oude Meulen in Cape Town in 1879–1883 (C de B Webb and JB Wright, A Zulu King Speaks: Statements Made by Cetshwayo kaMpande on the History and Customs of His People (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press and Durban: Killie Campbell Africana Library, 1978)) are recorded as making beaded items for sale to those who visited the king (RCA Samuelson, Long, Long Ago (Durban: Knox, 1929), 118) and some of these may well have ended up in collections deposited in museums.

15. While totalising histories of beadwork, such as implied in this claim, are acknowledged as being problematic because there are too many variants in practice (not only between ‘ethnicities’, but within them), specific instances can be demonstrated with reference to individual objects or specific object types over a long period of time.

16. JW Colenso, ‘On the Efforts of Missionaries Among Savages’, The Anthropological Review 3 (1865), ccxlviii– cclxxxix, mounted a trenchant critique of these requirements, which have been discussed by a number of authors vis-à-vis the Natal towns, but less fully with regard to the isiXhosa-speakers in the Eastern Cape, although Shaw and van Warmelo (‘The Material Culture’, 620) place its origin with Lord Charles Somerset’s interdiction against indigenous costumes in colonial towns. Somerset was governor of the Cape from 1814 to 1826 and the engineer of the 1820 settlement of English emigrants.

17. Inanda Seminary was established by a Mrs Edwards (Tyler, Forty Years). There are many other examples – one was at St Cuthbert’s Mission at Tsolo in Mpondomise territory (Callaway, Building).

18. Again, the division of labour varied from one ethnic group to another; see S Klopper, ‘Home and Away: Modernity in the Art and Sartorial Styles of South African Migrant Labourers and Their Families, in The Visual Century: South African Art in Context, Vol 2, ed. L van Robbroeck (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2012), 121–139. Shaw and van Warmelo (‘The Material Culture’, 536) date the change to the use of cloth skirts among isiXhosa-speaking women to 1820.

19. S Klopper, ‘Home’, 125. Traders still stock blankets, which are identified according to ethnic group preferences – particular stripes among Ndebele, patterns with maize cobs among Sesotho-speakers and off-white with dark edge stripes among isiXhosa speakers.

20. The same scene appeared in the London Illustrated News of 18 September 1886, but reversed. D Baghat identifies each of the men by name and ethnic allegiance (according to their dress): from right to left: Silas, a Gcaleka; Mfeana, a Fingo (Mfengu); behind the cradle, a ‘bushman’, Klaas Jaer; and at left, a ‘Tambookie Kafir who had served the government for 20 years’ (‘Buying More Than a Diamond: South Africa at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition 1886’, MA thesis, Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal College of Art, London, 1996). Frank Cundall called the latter ‘a Krooman, James Stuart’ in Reminiscences of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition (London: William Clowes, 1886), 88.

21. S Klopper, ‘Art’, 31.

22. W Beinart, The Political Economy of Pondoland, 1860–1930 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982) and J Peires House, both address the structural changes in homestead power relations, but Beinart does not really consider it from women’s point of view.

23. The organisation of young men (and women) into regiments in the Zulu kingdom meant that young men, in particular, could be away from their family homesteads for long periods (J Laband, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Kingdom’, in Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, ed. B Carton, J Laband and J Sithole (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2009), 87–95). This system was replicated in many other polities. Among Xhosa, Sotho, Ndebele and Tsonga, young men would be absent for some time during their initiation into manhood and sometimes on hunting or cattle-raiding trips, or in times of war.

24. P Dlamini, Servant of Two Kings, compiled by H Filter, translated and edited by S Bourquin (Durban: Killie Campbell Library Publications, 1998: 22) recounted to Reverend Filter, from her experience, that special beadwork had to be taken by young women who were placed by the families in King Cetshwayo’s izigodlo (women’s quarters), after which they were no longer part of their paternal families.

25. S Klopper’s discussion in ‘Home’ as to why men returned home from the mines on a regular basis does not consider these, more spiritual elements of the question.

26. S Klopper, ‘Art’, 31, suggests that there is a binary operating among Eastern Cape peoples between the women who stayed at home invisibly making the beadwork and the men who wore it publicly, but the photographic evidence suggests that women wore beadwork sometimes almost as lavish as that worn by men. This is also clearly the case for the isiZulu-speakers of Natal and the Ndebele and Tsonga of the Limpopo province. The particularly white beadwork worn as a special marker by isiXhosa-speaking practitioners of healing and divination could be made by male and female ritual specialists themselves.

27. Broster, Tembu; Costello, Not Only.

28. See Mertens and Broster, Elegance on the Xhosa – they distinguish between the various isiXhosa-speakers more carefully than other writers. Mertens and Schoeman, The Zulu offer some examples of regional differences in Zulu beadwork, as do E Preston-Whyte and J Morris, Speaking with Beads: Zulu Arts from South Africa (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994). I Powell, Ndebele: A People and Their Art (Cape Town: Struik, 1995) gives an overview of Ndebele beadwork, and A Nettleton, ‘Breaking Symmetries: Aesthetics and Bodies in Tsonga-Shangaan Beadwork’, in Dunga Manzi/Stirring Water, ed. N Leibhammer (Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery and Wits University Press, 2007), 79–102 of Tsonga beadwork.

29. VZ Gitywa, ‘The Arts and Crafts of the Xhosa in the Ciskei: Past and Present’, MA thesis, University of Fort Hare, Alice, 1970, 54–55.

30. C van Onselen, Studies in the Social and Economic History of the Witwatersrand, 2: New Nineveh (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1982).

31. Alfred Duggan-Cronin started out photographing people on the mines dressed in ethnic costume – this led him to explore rural areas and photograph people in their apparently ‘pristine’ state. The published photographs appeared in a series called The Bantu Tribes of Southern Africa over the period 1928 to 1939. See, for example, A Duggan-Cronin, The Bantu Tribes of Southern Africa: The Vathonga, vol 4, section 1 (Cambridge: Deighton-Bell, 1935).

32. I argue this against claims made in some of the literature, where beadwork made by women for women is often illustrated, but not really discussed. See, for example, Costello, Not Only and Van Wyk, ‘Illuminated’.

33. R Papini, ‘The Stepped Diamond of Midcentury Zulu Beadwork: Aesthetic Assimilation Beyond the Second Izwekufa’, in Oral Tradition and its Transmission, eds E Seinart, N Bell and M Lewis (Pietermaritsburg: University of Natal Press, 1994), 27–46.

34. This image appears in Stevenson and Graham-Stewart, South East, 20, labelled ‘Zulu Warriors’, a postcard published in 1907, but its earlier iteration, in this case housed in the Museum Africa archives in Johannesburg, does not bear the inscription and it corresponds closely to other photographs taken in the same location in the 1890s.

35. There has been a great deal of ink spilt about the meaning of such love letters. Despite recent attempts to codify the language of colour and pattern in so-called Zulu beadwork, there is no clear syntax and no clearly established vocabulary that allows for any standard reading of any of the beadwork. All ‘meanings’ were entirely contextual. See M-L Labelle, Beads of Life: Eastern and Southern African Beadwork from Canadian Collections (Gatineau: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2005) for a measured rebuttal of such claims.

36. This date is approximate, based on evidence from early collections in the British Museum, in Vermont and elsewhere, made by missionaries and travellers in Natal.

37. There are voluminous numbers of such group photographs made for the postcard industry in collections and museums in South Africa and abroad; see, for example, VL Webb, ‘Fact and Fiction: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of the Zulu’, African Arts 25.1 (1992), 50–59, 98–99. The constructedness of this image is reinforced by the possibly accidental presence of a black, possibly leather, garment draped over the background vegetation between the central figure and the man to the right.

38. See A Nettleton, J Charlton and F Rankin-Smith, Engaging Modernities: Transformations of the Commonplace (Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand Art Galleries, 2003).

39. Mertens and Broster, Elegance, plates 16 and 97.

40. Costello, Not Only; D Bunn, ‘Obscure Objects of Desire’, in Voice Overs: Wits Writings on African Art Works, eds. A Nettleton, J Charlton and F Rankin-Smith (Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersand Art Galleries, 2004), 22–23.

41. Costello, Not Only, 77. Costello further suggests that these items were considered amongst the most desirable forms of beadwork that a woman might make for a man.

42. See, for example, the jodhpurs worn by an induna in a photograph taken by Katesa Schlosser in K Schlosser, Zulu-Hochzeiten im Kulturwandel: Photographien von Hochzeiten auf dem Cezaberg im Herzen des Zululandes und von den Kralen prominenter Hochzeitsgäste (Kiel: Museum für Völkerkunde der Universität Kiel, 2004). Other photographs taken by Schlosser in Natal show how completely integrated beaded and Western items had become by the middle of the twentieth century in this region.