Exercise 6: Present Moment, Wonderful Moment

Exercise 6: Present Moment, Wonderful Moment

It’s okay to be laying down your tool addictions, because I have something better for you to use. Replace your tool addictions with tools that actually promote positive action and growth.

This chapter is your toolshed. Come back here to get a tool whenever a job gets too tough for bare hands.

An addict’s typical response to new tools—when she’s thinking with an addicted mind—is something like this:

So tune in to the first three Steps for a moment to get yourself back into your recovering mind.

Good. Like many of us, you’ve admitted that you need help. These tools help. They give you various ways to stay conscious and focused. And they can improve your mood so that you don’t have to resort to any tool addictions or behaviors.

Living mindfully brings you into consciousness of the good that is already surrounding you. You have the gift of a splendid day arrayed before you. Pause. Settle. Breathe. Take it in. Something within sight is beautiful, intricate, or meaningful.

You are alive right now. Focus into this one moment. You have everything you need in this moment.

Experience more right now. Be in the present. Following is an exercise from a helpful guide to mindfulness, Peace Is Every Step.1

Exercise 6: Present Moment, Wonderful Moment

Exercise 6: Present Moment, Wonderful Moment

Sitting in a comfortable position, say the following lines in coordination with breathing in and breathing out:

Breathing in, I calm my body.

Breathing out, I smile.

Dwelling in the present moment,

I know this is a wonderful moment!

After getting used to this sequence and letting the meaning percolate into your cells, shift into these lines:

Calming, smiling,

Present moment, wonderful moment.

No matter what else you may be feeling, stopping and being mindful takes you back into reality—the larger reality often obscured by your racing mental motor. In this moment, you have what you need. A bird is singing. The air is soft on your skin. We often think we need to suppress our anger, but Thich Nhat Hanh, a world authority on peace, has alternate advice. He writes:

When our anger is placed under the lamp of mindfulness, it immediately begins to lose some of its destructive nature. We can say to ourselves, “Breathing in, I know that anger is in me. Breathing out, I know that I am my anger.” If we follow our breathing closely while we identify and mindfully observe our anger, it can no longer monopolize our consciousness.

When we are angry, we are not usually inclined to return to ourselves. We want to think about the person who is making us angry, to think about his hateful aspects…. The more we think about him, listen to him, or look at him, the more our anger flares … but, the root of the problem is the anger itself, and we have to come back and look first of all inside ourselves…. Like a fireman, we have to pour water on the blaze first and not waste time looking for the one who set the house on fire.

“Breathing in, I know that I am angry. Breathing out, I know that I must put all my energy into caring for my anger.”

When we are angry, our anger is our very self. To suppress or chase it away is to suppress or chase away our self. When we are joyful, we are the joy. When we are angry, we are the anger.2

Grounding gives roots to mindfulness by combining mindfulness with connection to the earth.

Grounding yourself is easy. Go outside and lean against a tree. Stand barefoot on the soil. Lie spread-eagle on the ground. Picture roots spreading out from your feet into the earth. Feel the life force of the tree or the soil.

This honors your physical body, the materials of which all came from the earth. Breathe the earth, drink the air, eat the sun.

Addicts tend to blame themselves or others. Sadly, we have precious little control over the actions of our parents, mates, or bosses. We can set boundaries to stop them from hurting us, but we have no control over their choices or their ability to treat us fairly or kindly.

Misery addicts who sacrifice themselves routinely operate under this principle: “If I give you what you need, you will give me what I need from you.” (In other words, “If I fill you up, you’ll pour goodies back on me.”) It’s a fair and reasonable principle, but it’s often 180 degrees from the truth. We could drench an angry or dependent parent or spouse with energy or love—for years or even decades—and get little or nothing back (or, worse, get back abuse). We don’t want to face the fact that the tree is barren. But we won’t get fruit from it no matter what we do.

In our disappointment that our sacrifice hasn’t done us any good, we may express our anger by blaming—ourselves for wasting the effort or the other person for taking without giving back. Blame won’t cause the person to give us anything, and blame won’t give anything to us.

We have no power to get another person to feel his own feelings, handle his own issues, or change his values. We are powerless to force someone else to take in or appreciate what we have to offer.

Truth? Now that’s another matter. Blaming and telling the truth are different species. Blame puts the focus on the other person. Truth observes the reality. Telling the truth lets you understand the other person, yourself, and your relationship.

Telling yourself the truth—which is a far different thing from blaming—allows you to stop squandering energy on someone who won’t change. It is enormously helpful when you can admit to yourself, “No matter what I give her, she still won’t understand me.” “He was abusive—that’s just the reality.” In telling yourself the truth, you can stop yourself from watering a plant that will never bear fruit.

These principles also apply to the way you talk to yourself. Hanh wisely writes, “When you plant lettuce, if it does not grow well, you don’t blame the lettuce. You look into the reasons it is not doing well.”3

Blaming yourself for not having lived your life differently is like blaming lettuce for growing slowly. You grew as you did because of the way you were watered and fed.

Allow yourself to understand this. This is telling yourself the truth.

Now, realizing this, you can put your attention to giving yourself the nourishment you were looking to get from the barren tree by going to a different orchard where the trees are heavy with fruit (like a recovery meeting).

In his book Nonviolent CommunicationSM *: A Language of Life, Marshall Rosenberg offers a powerful tool to improve our communication—not just with others, but with ourselves.

Learning this system gives you a different way to listen to others and greater clarity and competence in how you respond to them. It gives you protection from others’ harmful communication, no matter how overt or subtle they may be about it, and it increases your odds of communicating in a way in which everyone is satisfied.

First, let’s look at communication styles that aren’t productive.

Here are the components of compassionate communication:

This structure can be used both for the way you express something to another person and for the consciousness you use as you listen to someone else. Neither you nor the other person has to use a particular formula in speaking.

In the pages that follow, I’ll review the essence of Rosenberg’s enormously helpful system.4

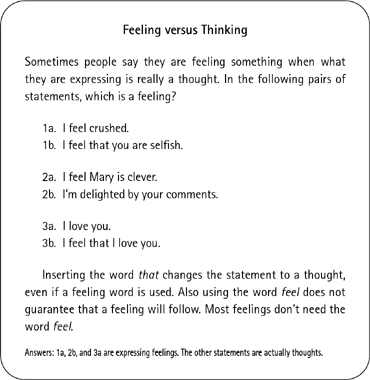

Learn to separate your observations from your evaluations. Simply observe what you are seeing, feeling, touching, and hearing (and sometimes smelling or tasting), and realize that your observation is distinct from your conclusion, opinion, belief, or judgment.

Another piece of this important distinction is being clear with others that something is your own evaluation or opinion (“I thought the play was really dull”) rather than stating your opinion as if it were a fact (“That play sucked”).

To get a taste of this, compare both parts of each of these sets of statements:

Expressing your feelings, either to yourself or to others, brings you personally into the picture, especially when you follow a statement of observation with a statement of your feeling about it. Identifying and expressing your feelings requires that you look into yourself, notice your feelings, and say what those feelings are.

Here are some examples:

We may be hurt by something someone else does or says, but no one forces us to feel. Our feelings arise from inside us as a result of our unique mix of issues, history, vulnerability, awareness, and needs. Our personal degree of vulnerability varies according to our mindfulness, centeredness, tiredness, and stress level, much of which we can make choices about.

Listen to—and feel—the difference between these two statements:

We often think the reason for a feeling is obvious. And if the second statement had included only the feeling half of the sentence—“I was hurt when you canceled our anniversary date”—we might say, “Of course he’s hurt. Anybody would be.”

That may be true, but Ed could be hurt because he’d been looking forward to time with Edna without the kids, while Paul might be hurt because he was planning to wow Paula with a brass band and a skywriter, and now his plans and money are down the drain.

Revealing the thoughts or hopes behind a feeling conveys more meaning, and that lets both you and the other person know more about you.

Behind most feelings are needs. Paying attention to what you need and expressing that need is your best chance at getting it fulfilled.

One of the best communication tools is a clear, straightforward request. Here are some helpful guidelines:

Here are some examples of these principles:

When you listen to others, offer them the same compassion and attention that you’d like from them. Here are Rosenberg’s components of compassionate responding:

Although Rosenberg’s system is intended for use in relationships with others, it also works splendidly in your communication with yourself.

Misery addicts are often divided inside. Faction one is determined to protect the self from being hurt. Faction two wants to experience more good in life.

The protective part, faction one, usually feels very young. This is because at a tender and vulnerable age you had to come up with a way to survive. You developed principles to minimize the harm that was done to you, and these led to strategies and decisions that are still operating today. Faction one has amazing strength and at times is more powerful than your own adult mind (faction two).

One way to connect your two factions is to use these same techniques of communication: observe an action, express your feeling about it, explain the need, and make a clear request. Then the other side listens, paraphrases, and responds.

I encourage you to try talking faction to faction out loud so that the process is clear and memorable. It can also be exceedingly enlightening to set up two chairs, one for each faction, and to switch chairs as each faction speaks. (Don’t do this in public, of course, or in front of anyone who won’t understand and appreciate what you’re doing. Although the process is very valuable—and very sane—to someone familiar with it, it may look either crazy or like some Acting 101 assignment to the uninitiated.)

Here are some examples of the process:

It sounds so simple. It’s easy to dismiss the power of gratitude. But the truth is that gratitude is incredibly powerful.

Most days, for most people, something goes right. A misery addict can easily miss it though, especially if she’s feeling grouchy, depressed, or frightened—and if she’s looking for (or expecting) things to go wrong.

This is why it’s a good daily practice to keep a simple gratitude journal. At the end of each day, just take five minutes to list five things you are grateful for. That’s it. Do this for one month and observe what happens.

Keeping a gratitude journal removes our dark glasses. At first we may have to look hard to find something to put in it, but over time it gets easier, and we feel more and more positive about ourselves and our life.

Many in recovery, especially women, have been physically or sexually abused, and some have been pressured by religious figures or traditions to forgive their abusers. But there’s a potential problem here.

When we think of forgiveness as letting the abuser off easy or saying it was okay to cause us harm, we only damage ourselves further. Premature forgiveness cuts off our essential feelings of anger.

Consultant and speaker Constance Wolfe, M.S.W., teaches that there is a difference between spiritual forgiveness and psychological forgiveness.6 Psychological forgiveness happens when we’ve processed our pain as deeply as necessary and we are able to let go of the person who harmed us. We have to wait to do this kind of forgiving until it’s a natural outgrowth of our recovery process.

Spiritual forgiveness is different—it’s a spiritual release of the other person. This we can do at any point. For example, we can think, I forgive you from my spiritual nature. I forgive you spiritually, knowing that your highest self would not have chosen to harm me.

But we don’t use spiritual forgiveness to tell ourselves that we didn’t get hurt. We continue to know the truth about what happened to us.

Spiritual forgiveness allows us to release our resentment.

For emergencies, fasten on this tool belt. If something happens that upsets you or threatens your recovery, use one of the following tools.

Make the MOST of your day:

Make Hay/Mine for Gold

Opposite Action

Steps

Talk

If a feeling upsets you, take advantage of it. Use the Healthy Feeling Process from chapter 26 to find out about yourself. Make hay while the feeling strikes. Mine for the meaning. It could be a new twist on an old issue or just a warning shot that you need to take better care of yourself. Pay attention to it and let it inform you.

Do the opposite thing from what you traditionally do to avoid or hide from the situation. If you usually get silent, deliberately speak. If you usually run away, stay. If you let others go first, you go first. If you sacrifice, ask for what you want. If you push yourself, rest. If you isolate yourself, call a friend.

Say the first three Steps of the Twelve Steps, out loud if possible.

Or use the quickie version: “I can’t. God can. I’ll let Her.”

Call a recovering friend or your sponsor, and tell him what’s happening to you and how you feel. For a cherry on top, ask for comforting words and a virtual hug.

* Service mark for the Center for Nonviolent Communication (www.cnvc.org).