Key points

- The most feared complications of diabetes are visual loss, kidney failure and amputation, due to Type 2 damaging small blood vessels in the eyes, kidney and nerves supplying the feet.

- The risk factors for these complications – high blood glucose, high blood pressure and high cholesterol – are the same as for heart attacks and strokes discussed in Chapter 9.

- Annual retinal photographs reliably identify early complications at the back of the eye – diabetic retinopathy. Severe eye complications have fallen since the national photographic screening programme was established in 2008.

- Annual blood and urine tests pick up early kidney complications (diabetic nephropathy), though they may not have been as successful in reducing serious complications as the eye programme. Fortunately, the risks of severe kidney disease have fallen over the past 20–30 years.

- Use the portfolio approach to prevent complications. Simple specific medication (for example, ACE inhibitors) combined with attention to blood glucose and cholesterol levels reduces the kidney risk, and probably helps the eyes too. Specialist eye doctors (ophthalmologists) now have sophisticated drugs, laser and advanced surgical techniques for the small number of people who develop serious retinopathy.

- We don’t have specific treatments for most of symptoms caused by impaired nerve function in the legs (neuropathy), but looking after your feet very carefully does a lot to prevent serious complications.

Small vessel complications of diabetes

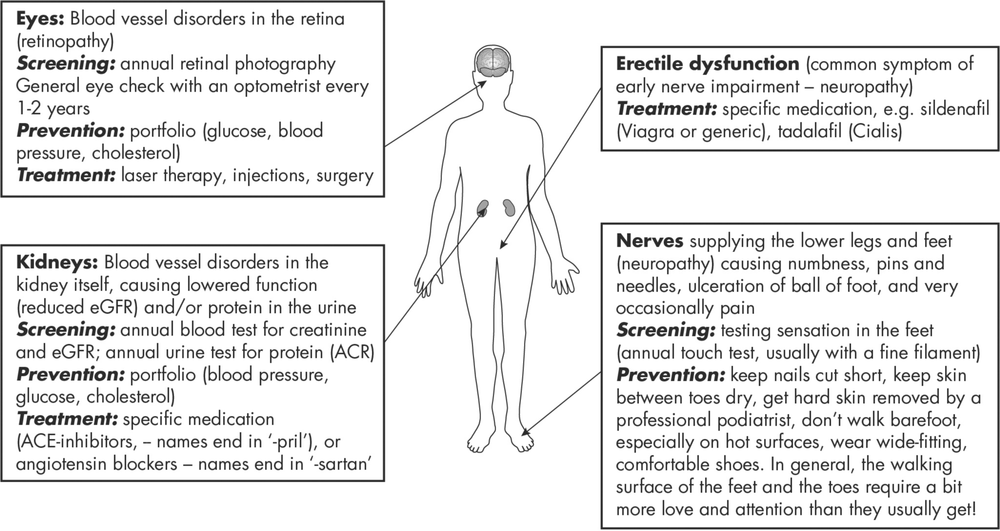

The impact of diabetes is mostly on blood vessels, and since blood vessels are everywhere, diabetes can have effects almost anywhere in the body. We discussed diabetes and the large artery complications – heart attacks, strokes and peripheral vascular disease affecting blood vessels to the legs and feet – in Chapter 9, but smaller blood vessels that supply the deeper parts of body structures are also affected. In most people, damage is minor or doesn’t occur at all and has no long-term consequences, but some people develop progressive complications in the vessels of the retina of the eyes, or the kidneys, or the nerves, and vision and kidney function can be affected. Figure 11.1 summarises these complications, known collectively as ‘microvascular’ problems, that is, affecting small vessels.

Eyes (diabetic retinopathy)

The NHS has a good screening service for the specific retinal complications of diabetes, and in the UK and other countries where similar annual screening services have been established, the numbers of people losing vision from retinopathy have fallen dramatically. Even the most difficult retinal complication – maculopathy, which impairs vision because it involves the small area of the retina which we instinctively use to focus on fine details – is likely to become less common because there are new and highly specific drugs that, when given by injection directly into the eye, help stabilise the structure of the retina.

In gloomsville articles on complications written by ‘experts’, we always used to kick off with the shock-horror line: ‘diabetic eye disease is the commonest cause of visual loss in people of working age’. Well, it isn’t any longer, and in fact hasn’t been since 2010. Although understandably feared, visual loss from diabetes is extremely rare these days. And that’s been a massive change: when I first became a consultant in the mid-1990s, the sad sight of white sticks and guide dogs in the diabetes clinic wasn’t that uncommon. In the last 10 years of my hospital clinics, I knew only a tiny number of people who had lost vision from diabetes.

Figure 11.1: A summary of complications of Type 2 diabetes resulting from disorders of small blood vessels (‘microvascular’ complications), emphasising screening for early involvement.

Why has this welcome change occurred? Although the screening programme was important, other factors must have been involved, because visual loss from diabetes was already falling before retinal screening was up and running in England and Wales in 2008. Was it better blood glucose control? Possibly: a major clinical trial (ACCORD EYE) found that low blood glucose levels maintained for a few years did have some effect in the long term on reducing eye complications. Surprisingly, lower blood pressure didn’t have any effect. This trial can’t explain the overall reduction we saw across England and Wales. In truth, we don’t have an explanation, but it’s definitely not due to a magic silver bullet. As we’ll see shortly when we discuss kidney disease, we need to get used to thinking about a medical ‘portfolio’, just as we do with a dietary portfolio like the Mediterranean diet. Keeping everything we can (glucose, blood pressure and cholesterol) under reasonable control certainly adds up to better outcomes in the long term (see the Steno-2 study below).

The commonest eye complication of diabetes is cataract, which occurs at an earlier age than in non-diabetic people. But treatment is just as simple and effective – day case surgery.

Key point: The annual photograph detects any early problems in the retina at the back of the eye, but everyone, with or without diabetes, can develop other eye troubles. You should visit your optometrist every year for a general eye check-up.

Kidneys

Let’s first recall the USA data from 1990 to 2010 shown in Chapter 9, Figure 9.1: the numbers of diabetic people requiring dialysis for kidney failure fell by 50%. I imagine the same has happened in the UK. But there is still a problem. Diabetes is no longer the commonest cause of blindness, but, in spite of the welcome decrease, it still heads the list of causes of kidney failure requiring dialysis. Fortunately, only very small numbers (about one in 1000) of Type 2s ever develop severe kidney failure – and of those, about one half get a kidney transplant. (The situation with transplants reminds us of coronary artery bypass graft operations; people with diabetes were previously not accepted for kidney transplant because it was thought they had a much higher risk of complications after surgery, including losing their new kidney through infection or rejection. That’s no longer the case, and many people with both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes now have completely successful kidney transplants.)

Estimating kidney health with blood and urine tests

But of course nobody wants to get anywhere near the point of needing a transplant. And among all the complications of Type 2 diabetes, kidney disease is very successfully prevented using a portfolio of standard diabetes treatments. Annual blood and urine tests give the best information. The blood creatinine concentration was previously the standard test of kidney function, but this has been replaced over the past few years by a measurement based on creatinine, but mathematically corrected for age, ethnicity and whether you’re male or female. This is the ‘eGFR’ (estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate). The eGFR number reflects how well the kidneys filter impurities from the blood. Creatinine accumulates in the blood as the kidneys become less efficient, but the efficiency of filtration decreases, so as blood creatinine goes up, eGFR falls. The kidney experts have started classifying the severity of kidney disease according to eGFR. Although eGFR measurements are important, we have become a bit fixated on the precise numbers, much as we saw happening with glucose levels that define ‘diabetes’ or ‘pre-diabetes’. Numbers always need an additional ingredient – specialist experience – to avoid the risk of raising unnecessary anxieties in people with diabetes, and this applies particularly to older people.

The other really important measurement is how much protein there is in the urine. Normally there should be none, but as diabetes begins to stress the kidneys, especially if blood pressure is high, tiny amounts of protein (albumin is the protein that’s measured) leak into the urine. Previously we used urine dipstick tests, but they don’t register the tiny amounts signifying early stress, so although we still use sticks as a routine test when you attend your GP or hospital for a diabetes review, there is also a laboratory urine test called ACR (albumin creatinine ratio). Because it’s repeated every year, over the course of time any trends can be detected.

Using these two tests – eGFR in the blood, and ACR in the urine – we can make a reasonably accurate assessment of the state of health of the kidneys. Interestingly, the same two measurements give just as accurate a risk of heart attack as the likelihood of developing kidney failure. It’s not clear why two kidney-based tests should be able to predict heart disease, but it’s been known for many years. Fortunately, the treatments of both very early kidney trouble and the associated heart risk are nearly identical. We know this because of a brilliant clinical trial done at one of the most famous diabetes hospitals in the world, the Steno Institute in Denmark. Though the name of the study – Steno-2 – wasn’t very exciting, the results of the study were (see References, page 231).

Key point: The results of blood and urine tests when combined give a good estimate of the risk not only of kidney disease, but of heart attacks. The risk factors for both conditions are broadly similar – blood glucose, blood pressure, cholesterol, weight and exercise.

Steno-2: Portfolio Scandinavian diabetes care

Steno-2 was a long study, running for about eight years; kidney disease takes a long time to develop. The people included were already at higher risk of kidney and heart disease because they had persistently slightly high levels of protein in the urine (elevated ACR). The idea was simple: use a portfolio of simple treatments – that is, control blood pressure, blood glucose and cholesterol, and encourage people to lose weight, stop smoking, eat healthily and exercise. Medication included a statin, low-dose aspirin and one of the blood pressure drugs that specifically target the kidneys (an ACE inhibitor or ARB; see Chapter 10). One group was supervised every few months in the hospital clinic (the ‘intensive’ group); the other had community care under their general practice team.

After the eight years in the study, the intensive group had lower levels of diabetic eye disease (retinopathy) and progressing kidney disease, and heart attacks were nearly 50% lower. After another five years, during which both groups were encouraged to look after themselves as well as possible (and medication was introduced as necessary in everyone who needed it), the group previously intensively treated had a 50% reduced risk of heart disease, including death from that cause. Serious eye disease requiring laser treatment was 60% lower, and only one person needed dialysis, compared with six in the group treated less intensively during the trial. After a very long follow-up period, the intensively treated group had lived on average eight years longer, mostly because they had less heart disease.

Was a huge amount of treatment needed here? And did glucose and blood pressure measurements have to be very low? Nothing of the kind. Blood pressure was good, and patients achieved the levels we currently recommend (130–140 mm). Blood glucose control using the HbA1c test was 7.7% (61 mmol/mol), and cholesterol 3.8 mmol/l. These are relatively easy values to achieve in nearly everyone – and note the blood glucose level was reasonable, but not by any means low. The message is very encouraging: using relatively small amounts of well-targeted medication and attention to weight, diet and exercise, we can get remarkable results, with very low risks of severe kidney disease and a major reduction in heart attack rates.

Key point: In people at higher risk of diabetic kidney complications, good blood pressure and cholesterol control with moderately good blood glucose control over a period of about eight years had a major beneficial effect on nearly every diabetic complication, not just kidney disease.

Combining moderately tough portfolio treatments together has a disproportionate effect

I apologise, but only a little, for my detailed description of the Steno-2 trial, which should have hit the headlines, but didn’t. The results were remarkable, but therapy didn’t involve earth-shattering drugs or technology, and the input into lifestyle wasn’t especially intensive, yet complications that really matter (heart disease, eye disease and advanced kidney disease) were all reduced by an enormous amount, and life expectancy increased. A set of therapeutic portfolios – modest input into everything related to diabetes – achieved great things. Because of this the people doing the trial couldn’t easily analyse if there was any single input that contributed the most to these good results, but their hunch was getting the cholesterol down with a statin was the most important, not, as you might imagine, reducing blood glucose levels.

Neuropathy

Like kidney and eye complications, neuropathy – diabetes affecting the nerves to legs, arms and internal organs – used to have terrible outcomes, most frighteningly the loss of legs. This is another fearful complication that is much less common now, and, like all the other complications, is less frequent because Type 2 diabetes is generally looked after better than even 10 years ago, You understand now that controlling blood glucose levels is probably not the only aspect of treatment that has reduced neuropathy: blood pressure, cholesterol, and lifestyle (exercise, weight loss and stopping smoking) are equally important, and probably more so.

However, in people with 10 or more years of Type 2, numb toes, tingling of the feet and occasionally pain in the legs are still quite common. These symptoms, troubling though they are, don’t mean that the foot or leg is threatened – but you need to be especially careful to look after your feet because the nerves relaying sensation from the feet to the brain are not fully operative, and your feet may be less sensitive, especially to heat and sharp pain. In spite of decades of research, there are no drugs that help repair nerves, but it’s simple to prevent the most serious complication of neuropathy, foot ulceration.

- Ensure toenails are cut cleanly and frequently (if you can’t reach or feel your feet properly get someone else to cut your nails).

- Dry thoroughly between the toes, where bacterial and fungal infections can lurk.

- If you have dry, thickened or cracked feet, moisturise with hydrating cream (for example, one of the Flexitol range).

- Never walk barefoot, especially on hot surfaces (beaches and marble floors in hot climates are a particular hazard).

- Wear well-fitting shoes (fashionistas beware – designer shoes aren’t designed with diabetes in mind), and check for gravel, stones and other objects in them.

This is hardly high-tech advice but, like many of the other treatments we’ve discussed in Type 2 – it works.

Foot ulcers

We discussed what happens when the large blood vessels to the feet fail to carry enough blood in Chapter 9. Poor blood supply can lead to ulcers of the feet, often associated with pain, but a much more common reason for developing foot ulcers is poor sensation resulting from inefficient nerves. These ulcers usually develop in areas of the feet subjected to pressure when walking, especially under the big toe, where very high pressures occur, further increased by hard skin or callus. Podiatrists are masters at managing callus and reducing pressure on the feet, and can spot trouble very early. If you’ve been told your feet are at higher risk, contact your local specialist podiatrist if there are any concerning signs: skin breaks, bleeding, red skin (infection/cellulitis) or pus. Prompt X-rays, possibly including an MRI scan, then treatment with antibiotics and the use of pressure-reducing casts and footwear can usually prevent further trouble. Amputation rates aren’t zero yet, but prompt and meticulous care has certainly contributed to reducing the need for surgery.

Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is common, affecting perhaps 20 to 40% of men. It is certainly the most common complication of nerve damage in diabetes, and may overall be the commonest diabetic complication. Treatments for ED used to be uncomfortable and not very successful, but drugs such as sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil (Cialis) have been remarkably helpful. Treatment combinations are often used by urology specialists when simple tablet-treatments aren’t fully effective.

Summary

The specific complications of diabetes caused by small vessel disease are less common, though they probably haven’t decreased as spectacularly as heart attacks and strokes. The portfolio approach works for all these complications – for example, keeping blood glucose levels between 6 and 10 mmol/l, resulting in an HbA1c value around 7% (53 mmol/mol), systolic blood pressure between 130 and 140, and cholesterol as low as possible. Even if it is difficult, for example, to keep the blood glucose levels to target, focus on the blood pressure and cholesterol – they are just as important as blood glucose, and in combination probably more so.