The first line of defense against infection is the unbroken skin. When the patient has suffered trauma to the body, this first line of defense is breached, thus allowing contaminating microorganisms to enter the wound. Once these microorganisms have contaminated the wound, they multiply exponentially,and, in twenty minutes, the number of Escherichia coli and Clostridium perfringens can double. 1

There is no greater medium for the growth of microorganisms than the battlefield-inflicted wound or similar “dirty” wound (Photo 20). Battlefield and other traumatic wounds are characterized by dead or dying tissue, the presence of foreign matter, and contamination by bacteria, all leading to wound infection. Baron Jean Dominique Larrey, Napoleon’s personal physician and surgeon, is said to have performed 200 amputations on the battlefield in a single day as the only recourse left for preventing infection. Predictably, more than 80 percent of these patients died anyway. 2

ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

Fortunately, advances in antibiotic therapy have reduced the need for amputations when the therapy is initiated in a timely manner. Around 1898, Friedrick established a parameter of 6 hours from the time a wound is inflicted and contaminated to the occurrence of an invasive infection. 3 It is imperative for the PHCP to begin aggressive antibiotic therapy for the traumatized patient in order to avoid the consequences of an infected wound. The PHCP’s guidelines for care should center around debridement and administration of antibiotics. Jacob and Setterstrom write:

Photo 20: This FDN trooper received this battle wound to his shoulder from an AK-47 rifle while deep inside the Esteli region of Nicaragua. The wound was not immediately life-endangering, but there were no antibiotics to be given in the field, and evacuation to a hospital took 10 days. In this photograph, a physician has radically debrided the shoulder in an attempt to stop the spread of gangrene.The patient’s arm was later removed in a last-ditch effort which failed to save this young soldier’s life. (Photo courtesy of D.E. Rossey.)

...surgical debridement and administration of antibiotics within as short a period of time as possible after wounding represents a crucial first step in the prevention of infection in open war injuries, factors which prolong the time of initial debridement can be expected to contribute to an increase in the incidence of wound infection. 4

For the PHCP, quick administration of a broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g., Ceftriaxone) to a patient who has suffered an open wound in the field is an appropriate initial response (Photo 21). Along this train of thought, Hell writes:

Prompt administration of antibiotics is of the utmost importance in the treatment of wounds inflicted during a war or disaster. A single injection of a broad-spectrum drug with a long half-life should be given prophylactically to personnel on the battlefield to provide bactericidal coverage from the earliest possible moment after injury occurs. 5

Photo 21: Vial of the broad-spectrum antibiotic Ceftriaxone. (Photo courtesy of Mike Mitchell.)

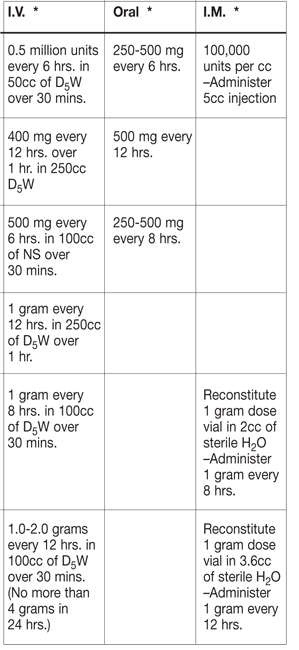

Once the patient has been stabilized and his wounds more closely evaluated, the PHCP should“target” if possible the specific types of bacteria that are commonly found in a particular type of wound.This approach to antibiotic therapy is based on the premise that the PHCP will not have the benefit of laboratory confirmation of the offending microorganism. With this cour se of action, the PHCP stands the greatest chance of administering the most effective antibiotic to the micro organism most commonly associated with a certain wound (Chart 1). Given the aforementioned lack of laboratory facilities, the PHCP must be particularly careful in dosing the antibiotic since there will be no way to determine when the therapeutic blood levels have been reached.

Chart 1: Dosing of the drug of choice. (Source: Scott Coffee, Pharm.D.)

*Dosings refer to drug of choice (column 3 on page 44).

Topical administration of antibiotics via powder, spray, or ointment should not be overlooked. The effectiveness of topical administration in conjunction with parenteral administration of antibiotics in combating development of local wound infection was proven in Vietnam, where only 16 percent of the patients treated in this manner developed local wound infection. 6 Sulfamylon,Polybactrin,and Neosporin are common topical antibiotics. The main shortcoming of topical administration is that it cannot reach bacteria located within the deeper portions of a wound. The PHCP must depend upon parenteral administration of the antibiotic to reach these deeply embedded microorganisms (Photo 22).

Photo 22: Common examples of IV-administered antibiotics. (Photo courtesy of Mike Mitchell.)

THE USE OF SUGAR TO ENHANCE

WOUND HEALING

The use of antibiotics by the PHCP in the field has the inherent dangers of improper dosing and allergic reactions. The associated activities of preparing the IV/antibiotic infusion and monitoring the IV drip rates can be difficult during patient transport. Given these drawbacks, the use of granulated sugar for the treatment of infected wounds offers a practical, proven approach for wound care. The use of granulated sugar for treatment of infected wounds is recommended bysome as a treatment of first choice. 7 Sugar has been called a nonspecific universal antimicrobial agent. 8 Based on its safety, ease of use, and availability, sugar therapy for the treatment of infected wounds is very applicable to the needs of the PHCP.

Sugar and honey were used to treat the wounds of combatants thousands of years ago. Battlefield wounds in ancient Egypt were treated with a mixture of honey and lard packed daily into the wound and covered with muslin. 9 Modern sugar therapy uses a combination of granulated sugar (sucrose) and povidone-iodine (PI) solution to enhance wound healing. 10

As with any traumatic wound, the wound is first irrigated and debrided. Hemostasis is obtained prior to the application of the sugar/PI dressing since sugar can promote bleeding in a fresh wound. 11 A wait of 24 to 48 hours before the application of sugar is not unusual. 12 During this delay, a simple PI dressing is applied to the wound. Once bleeding is under control, deep wounds are treated by pouring granulated sugar into the wound, making sure to fill all cavities. The wound is then covered with a gauze sponge soaked in povidone-iodine solution. 13 Superficial wounds are dressed with PI-soaked gauze sponges coated with approximately 0.65 cm thickness of sugar. 14 (Photo 23)

In a few hours, the granulated sugar is dissolved into a “syrup” by body fluid drawn into the ound site. Since the effect of granulated sugar upon bacteria is based upon osmotic shock and withdrawal of water that is necessary for bacterial growth and reproduction, this diluted syrup as little antibacterial capacity and may aid rather than inhibit bacterial growth. 15 16 So to continually inhibit bacterial growth, the wound is cleaned with water and repacked at least one to four times daily (or as soon as the granular sugar becomes diluted) with more solute (sugar) to “reconcentrate” the aqueous solution in the environment of the bacteria. 17

A variety of case reports provide amazing data supporting the use of sugar in treating infected wounds. Dr. Leon Herszage treated 120 cases of infected wounds and other superficial lesions with ordinary granulated sugar purchased in a supermarket. 18 The sugar was not mixed with any antiseptic,and no antibiotics were used concurrently. Of these 120 cases, there was a 99.2 percent cure rate, with a time of cure varying between 9 days to 17 weeks. Odor and secretions from the wound usually diminished within 24 hours and disappeared in 72 to 96 hours from onset of treatment.

Photo 23: Sugardyne is a commercially available sugar/povidone-iodine compound.Its proven antimicrobial properties make it particularly useful for infected wounds encountered in the field. (Sugardyne donated by Dr. Richard A.Knutson; distributed by Sugardyne Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Greenville, MS 38701.)

Like Dr. Herszage, Dr. Richard A. Knutson has had very successful results from the use of sugar in wounds. One of Dr.Knutson’s most unique cases is recounted as follows.

A 93-year-old man was treated at Delta Medical Center for a fracture of his right hip. Concurrently, he received treatment for an old injury to his left leg, sustained 43 years earlier in 1936,when a tree had fallen on the leg while he was chopping wood.He had sustained an open fracture of the tibia and soft tissue loss to the leg anteriorly. Although the fracture had healed, bone remained exposed, surrounded by a chronic draining ulcer 20 cm x 8 cm overall. The patient was able to recall the various treatments used in attempts to heal the ulcer—iodoform, scarlet red, zinc oxide, nitrofurazone, sulfa, and a long list of antibiotics—all to no avail. He said that he had outlived six of the surgeons who had advised amputation. He was started on sugar/PI dressings, and then changed to treatment with sugar/PI compound as an inpatient. After hip surgery, the ulcer healed completely in 13 weeks. The ulcer defect filled completely, and skin grafting was not necessary. 19

A CASE STUDY

A 19-year-old black man was treated for a shotgun blast to the right foot. The wound went completely through the foot,creating a 2.5 cm diameter hole on the dorsum of the foot and a 5 cm to 7.5 cm jagged wound on its plantar aspect. The wound was irrigated, debrided, and packed with iodoform. A similar procedure was done on his third hospital day. On day five and following, he was treated with whirlpool and sugar/PI compound and was ready for discharge, [having not taken] antibiotics in eight days. By seven weeks, the patient was nearly healed, with healing complete at nine weeks. He had minimal scarring with no requirements for skin grafting. (Photos 24 through 29) 20

Photos 24 and 25: Entry (top of foot) and exit wounds from a 12-gauge shotgun blast to the right foot. (Photos courtesy of Dr. Richard A. Knutson.)

Photo 26: Wound as seen on day one after it was irrigated and debrided. Note careful and complete removal of all damaged tissue. (Photo courtesy of Dr.Richard A. Knutson.)

Photo 27: Wound as seen after two and a half weeks of healing. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Richard A. Knutson.)

Photos 28 and 29: Healed wound at nine weeks. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Richard A. Knutson.)

1 Konrad Hell, “Characteristics of the Ideal Antibiotic for Prevention of Wound Sepsis Among Military Forces in the Field,” Reviews of Infectious Diseases, 1991, p. 165.

2 Ibid. p. 164.

3 Ibid. p. 165.

4 Elliot Jacob and Jean Setterstrom, “Infection in War Wounds: Experience in Recent Military Conflicts and Future Considerations,” Military Medicine, 1989, p. 313.

5 Konrad Hell, “Characteristics of the Ideal Antibiotic for Prevention of Wound Sepsis Among Military Forces in the Field,” Reviews of Infectious Diseases, 1991, p. 164.

6 Elliot Jacob and Jean Setterstrom, “Infection in War Wounds: Experience in Recent Military Conflicts and Future Considerations,” Military Medicine, 1989, p. 314.

7 A.G. Tanner, E.R.T.C. Owen, and D.V. Seal, “Successful Treatment of Chronically Infected Wounds with Sugar Paste,” European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 1988, p. 525.

8 Jorge Chirife and Leon Herszage, “Sugar For Infected Wounds,” The Lancet, 1982, p. 157.

9 A.G. Tanner, E.R.T.C. Owen, and D.V. Seal, “Successful Treatment of Chronically Infected Wounds with Sugar Paste,” European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 1988, p. 524.

10 Richard A. Knutson, Lloyd A. Merbitz, Maurice A. Creekmore, and H. Gene Snipes, “Use of Sugar and Povidone-Iodine to Enhance Wound Healing: Five Years’ Experience,” Southern Medical Journal, 1981, p. 1331.

11 Tamas Szerafin, Miklos Vaszily, and Arpad Peterffy, “Granulated Sugar Treatment of Severe Mediastinitis After Open-Heart Surgery,” Scandinavian Journal of Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery, 1991, p. 77.

12 Ibid. p. 77.

13 Richard A. Knutson, Lloyd A. Merbitz, Maurice A. Creekmore, and H. Gene Snipes, “Use of Sugar and Povidone-Iodine to Enhance Wound Healing: Five Years’ Experience,” Southern Medical Journal, 1981, p. 1331.

14 Ibid. p. 1331.

15 Tamas Szerafin, Miklos Vaszily, and Arpad Peterffy, “Granulated Sugar Treatment of Severe Mediastinitis After Open-Heart Surgery,” Scandinavian Journal of Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery, 1991, p. 80.

16 Jorge Chirife, Leon Herszage, Arabella Joseph, and Elisa S. Kohn, “In Vitro Study of Bacterial Growth Inhibition in Concentrated Sugar Solutions : Microbiological Basis for the Use of Sugar in Treating Infected Wounds,” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1983, p. 770.

17 Richard A. Knutson, Lloyd A. Merbitz, Maurice A. Creekmore, and H. Gene Snipes, “Use of Sugar and Povidone-Iodine to Enhance Wound Healing: Five Years’ Experience,” Southern Medical Journal, 1981, p. 1332.

18 Jorge Chirife, Leon Herszage, Arabella Joseph, and Elisa S. Kohn, “In Vitro Study of Bacterial Growth Inhibition in Concentrated Sugar Solutions: Microbiological Basis for the Use of Sugar in Treating Infected Wounds,” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1983, p. 766.

19 Richard A. Knutson, Lloyd A. Merbitz, Maurice A. Creekmore, and H. Gene Snipes, “Use of Sugar and Povidone-Iodine to Enhance Wound Healing: Five Years’ Experience,” Southern Medical Journal, 1981, p. 1333.

20 Ibid. pp. 1332 and 1333.