Pain control for the traumatized patient during wound management is not only a blessing to the patient but it benefits the PHCP as well. As the PHCP attends to an injury, his commitment to the procedure may begin to wane under the cries of his patient.

During the Napoleonic period, anesthesia for the wounded soldier was woefully lacking. There is an incident recorded in which a British and French soldier were lying next to one another while undergoing operations for battle wounds. The screams of the Frenchman “seemed to annoy the Englishman more than anything else, and so much so, that as soon as his arm was amputated he struck the Frenchman a sharp blow across the breech with the wrist saying, ‘Here take that, and stop your damned bellowing. ’’’1

Such patient stoicism is not often found, and old approaches to pain relief such as partial strangulation, alcohol, and limb numbing by tourniquet are now makeshift approaches for pain control. The PHCP is much better served if he is prepared to control his patient’s pain by one or a combination of the following approaches.

1. Local infiltrative anesthesia

2. Administration of narcotics

3. Dissociative anesthesia

4. Intravenous regional anesthesia

5. Regional nerve blocks

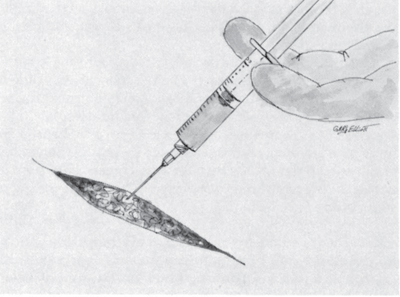

Repair and closure of most minor soft tissue wounds can be done under local infiltrative anesthesia. The “local” is simply the injection of the anesthetic into the wound site to bring about “deadening” of the nerve endings. The anesthetic is injected into the wound edges using a fine-gauge needle such as a 25 or 27 (Ill. 86). Repeated injections at various sites along the wound are often necessary. The anesthetic should be injected slowly, as fast injections can distort anatomy, inhibit blood supply, cause pain, and add tension to the tissue, which will impair wound closure. Needles should be replaced periodically throughout the procedure to assure a sharp point.

Illustration 86: Injection of an anesthetic into a wound. Several injections throughout the wound are usually needed to achieve the desired effect.

Lidocaine is a very common drug for a local, as are many of the “caine” family of drugs (Photo 65). Lidocaine is diffused rapidly into tissue. The maximum safe dosage of Lidocaine is 500 milligrams. 2 Care must be taken not to exceed this amount in patients with multiple lacerations or in those who require anesthesia in large volumes of tissue. In these cases, an alternative approach to pain control such as a regional nerve block may be more useful. Lidocaine toxicity can range from skin irritation to cardiovascular collapse. Attention must also be given to a patient’s allergic sensitivity to Lidocaine and related drugs.

Photo 65: Xylocaine, a commonly used drug for local infiltrative anesthesia. (Photo courtesy of Mike Mitchell.)

In 1903, Heinr ich F.W.Braun championed the addition of epinephrine to Lidocaine to delay Lido caine’s absorption into the vascular system, thus prolonging its anesthetic effects. 3 Due to epinephrine’s vasoconstrictive properties, it became known as a “chemical tourniquet. ” The vasoconstrictive properties of epinephrine are also useful in decreasing bleeding into the operative site during wound closure. When Lidocaine with epinephrine is used, it should not be injected into tissue that has limited circulation such as ears, nose, or fingers, since tissue damage can result.

Narcotic administration in the field has a long history of success due to its ease of administration and potent analgesic effects. Narcotics give the PHCP the ability to alleviate pain for a broader range of patient conditions and situations. Conditions such as a shoulder dislocation and situations such as expedient patient removal from the field often do not lend themselves to a “local” for pain control (Photos 66 and 67; Photo 68).

Photos 66 and 67: This patient’s dislocated shoulder was manuevered back into normal position without benefit of pain relief. Note his facial expressions during and after successful completion of the procedure. Administration of a narcotic would have made this procedure easier on everyone involved. Injury resulted from a fall from a rope bridge. (Photos courtesy of D.E. Rossey.)

Photo 68: This trooper is obviously in pain as he is removed from the field. If narcotics are given to a patient, it should be remembered that large dosing will cause the patient to relax to such a degree that he may become difficult to carry. (Photo courtesy of D.E. Rossey.)

Careful attention must be given when administering narcotics since they can compromise the patient’s vital signs, quickly causing the “bottom” to drop out of respirations. Administration of narcotics can be intramuscular, although the intravenous approach is preferred since it is more controllable. Morphine is usually administered by IV and titrated to the patient’s response to pain control. Since individuals possess different pain thresholds, it is best to “push” only that amount of drug that stops the pain. It is not a bad idea to have the narcotic antagonist Narcan available in case of accidental overdose of the narcotic. Narcan will help the patient who has suffered a morphine overdose on his way back to more stable vital signs.

Ketamine is known as a dissociative anesthetic since it induces in the patient a state of disinterest and detachment from his environment. 4 Ketamine is particularly useful for anesthetizing the severely traumatized patient because, unlike many anesthetics, it is less likely to produce hypotension. 5 Ketamine has been used with success in the following types of procedures: 6

1. Debridement and dressing changes in burn patients

2. Superficial surgical procedures

3. Dental extractions

4. Amputations

5. Closed reductions and manipulation of fractures

When administered via the intravenous route, the initial dose of Ketamine may range from 1 milligram to 4.5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. 7 Ketamine injected intramuscularly is generally given in a range of 6.5 to 13 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. 8 Ketamine is fast-acting, with anesthesia lasting only a short time. A dose of 2 milligrams per kilogram of body weight usually produces anesthesia within 30 seconds and lasts 5 to 10 minutes. 9 Should additional anesthesia be needed, further administration of Ketamine can be titrated to the patient’s response. As with any form of anesthetic, the PHCP must be attentive to fluctuations in the patient’s vital signs and the proper maintenance of an airway.

The use of intravenous regional anesthesia as advanced by Bier in 1908 is described as a relatively safe method of obtaining extremity anesthesia. 10 With a combination of bloodless exsanguination in the injured limb, inflation of a pneumatic tourniquet, and injection of a local anesthetic below the tourniquet, the anesthetic is confined to the area of injury, thus bringing about anesthesia.

Applied more often to the arm than to the leg, intravenous regional anesthesia is indicated for brief procedures (under 40 to 60 minutes in duration) ranging from manipulation of fractures to surgical procedures such as removal of foreign bodies and repair of lacerations. 11 The procedure is begun by inserting an IV catheter (plugged with a male adaptor) distally and as near to the wound site as possible. A blood pressure cuff used as a pneumatic tourniquet is now placed on the arm for operations to the forearm or hand and to the calf for operations to the foot. The blood pressure cuff is not inflated at this time.

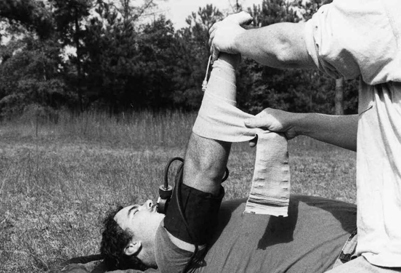

Once the IV catheter and blood pressure cuff are in place, bloodless exsanguination is carried out by elevating the limb for several minutes. With the limb still elevated, it is wrapped tightly with an Esmarch bandage (rubber bandage) or Ace wrap, beginning distally to the wound site and ending at the blood pressure cuff (Photo 69). 12 The blood pressure cuff is quickly inflated to 50 to 150 mm Hg above the patient’s systolic pressure. 13 With the blood pressure cuff left inflated and the Ace wrap removed, the limb should take on a mottled, cadaveric appearance.

Lidocaine in a 0.5-percent concentration is administered in a dosage of 3 milligrams per kilogram of body weight 14 15 (Photo 70). The injected Lidocaine spreads through the venous system and then diffuses into the tissues. The desired level of analgesia will develop in 10 to 15 minutes in those areas of the limb below the blood pressure cuff. 16 Lidocaine with epinephrine added should not be used, as it may restrict proper diffusion into the tissues. The inflated blood pressure cuff should not be left in place longer than 60 minutes; tourniquet pain, however, which usually develops after 40 minutes, will probably require removal of the blood pressure cuff. 17 18 It is this tourniquet tolerance on the patient’s part that has the greatest impact upon the duration of anesthesia. Occasionally, a tourniquet “wheel” of local anesthetic can be used to prolong tourniquet use. A “wheel” of subcutaneous anesthetic is injected just proximal to the blood pressure cuff application site circumferentially about the limb.19

Photo 69: Bloodless exsanguination of the arm by use of limb elevation and Ace wrap.

Following removal of the blood pressure cuff due to completion of the operation or the onset of tourniquet pain, sensation returns and paralysis disappears in just a few minutes. The use of a double-cuffed tourniquet generally does not bring about the onset of tourniquet pain as quickly as that of the single-cuffed blood pressure cuff. In the double-cuff arrangement, the proximal cuff is inflated first, then the local anesthetic injected. Once analgesia has been obtained, the distal cuff is inflated over what is now a “deadened” area. The proximal cuff is then deflated (Ill.87).

Photo 70: With the blood pressure cuff inflated to restrict blood flow, the anesthetic is being injected via IV.

Illustration 87: Use of the double- cuff tourniquet for intravenous regional anesthesia.

When the PHCP has completed the operation, he should not deflate the blood pressure cuff (tourniquet) until at least 20 to 30 minutes have passed from the time that the Lidocaine was injected. 20 Deflation of the cuff prior to this time span may result in toxic concentrations of Lidocaine being released into the bloodstream.

The regional nerve block is used when there is a need for long-lasting anesthesia over a rather large but specific area with a minimum amount of drug expenditure. Its main disadvantage to the PHCP is that it requires a certain degree of technical skill and thorough knowledge of anatomy to be employed properly.

The regional nerve block brings about analgesia by preventing nerve impulses from passing by the anesthetic that has been injected around a nerve trunk. The “deadened” nerve trunk may be some distance from the area in which the wound repair is to take place. A premedication such as morphine is sometimes given to the patient before a regional nerve block is performed. This premedication will benefit patients who interpret touch and motion as pain. For a regional nerve block to be successful, the PHCP must be precise in choosing the injection site. The anesthetizing drug must be localized in as small an area as possible and as close to the nerve as possible in order to bring about the desired effect and not cause complications.

It is a common practice to raise a wheal of injected anesthetic (e. g. , Lidocaine) just under the skin surface to provide a painless path for needle insertion and manipulation prior to injection of the anesthetic at the site of the sought-after nerve trunk (Ill. 88). As the needle is advanced carefully toward the nerve, attention is paid to indicators such as arterial pulsations through the needle and the onset of paresthesia.

Illustration 88: Formation of a wheal for heal anesthesia. A) Drop of anesthetic applied to the skin. B)Needle advanced. C) Wheal formed as the anesthetic is injected.

Paresthesia is the feeling of electrical shock or tingling often associated with nerve blocks. It can be painful, so the patient should be warned and advised not to move. When possible, the patient should be prepared to assist in the procedure by stating when paresthesia has begun. This will guide the PHCP in proper placement of the anesthetic. When paresthesias are elicited, less anesthetic usually is needed to bring about a successful block. However, when the needle has been properly placed anatomically and no paresthesias are elicited, several injections are made in a fanlike manner around the site to ensure anesthesia. When a block of the numerous small nerve branches that run off of a nerve trunk is needed, a circle of subcutaneous infiltration is carried out. (Ill. 89) This continuous wheal around a limb is known by names such as a garter band, wrislet, wheel, etc.

Illustration 89: Fan technique for anesthetic injection. Note that the needle is repositioned several times. Once inserted into the skin, changes in needle position are made with a slight withdrawal, then reinserted. The needle is not removed completely from the tissue when changing position. Bottom illustration shows overlapping continuous band of injected anesthetic.

The purposeful elicitation of paresthesia is controversial because of a reportedly higher risk of nerve damage as a result of the hypodermic needle piercing the nerve. 21 The needle should never be placed in a nerve, the objective being to inject the anesthetic around the nerve. 22 Paresthesia is very difficult to avoid due to the importance of placing the needle point as close as possible to the nerve. Its onset has the benefit of providing evidence of correct needle placement. To prevent injection into the nerve, however, the needle should be retracted slightly until the paresthesia ceases before injection of the anesthetic23

Once the PHCP is satisfied with his needle placement for the regional block, he should aspirate the syringe as a precaution against injection of the anesthetic into a vessel. If there is blood return into the syringe, the needle should be repositioned before the anesthetic is injected. The needle is never advanced up to its hub. Needles can break at the junction of the shaft and hub, making retrieval difficult.

(Uses: Provides anesthesia for forearm and portions of the arm.)

1. Anatomical landmarks: Axillary artery and pectoralis major muscle.

2. Patient positioning: With the patient lying on his back, his arm is abducted 90 degrees, with the forearm flexed at a right angle and lying flat on a table.

3. procedure:

A.A constrictive band (e. g. , Penrose drain) is tightened around the arm distal to the injection site. This procedure will aid in spreading the anesthetic cephalad, thus increasing the chances of a successful block.

Illustration 90: Axillary block of the brachial plexus.

B. The axillary artery is isolated and held between the index and middle fingers of one hand. A skin wheal is raised high in the axilla around the insertion point of the pectoralis major muscle on the humerus. The needle is inserted at a 45- degree angle towards the artery so as to enter the plexus. Penetration of the plexus is sensed by a sudden release and the needle will begin to pulsate with the artery. Paresthesia is another indicator of proper needle placement (Ill.90).

C. Inject anesthetic.

D. In a few minutes, remove constrictive band.

4. Precautions: If the axillary artery is entered by the needle, withdraw the needle before injection of the anesthetic.

1. Anatomical landmarks: Metacarpal bones.

2. Patient positioning: Place the patient on his back with the top of his hand facing upward.

3. Procedure:

A. Raise an intradermal wheal on each side of the midpoint of the metacarpal bone of the digit to be anesthetized (Ill. 91).

B. Advance the needle toward the palm, perpendicular to the skin.

C. Inject the anesthetic along the area from the wheal to the web of finger on either side.

4. Precautions: The PHCP should place his finger on the patient’s palm and palpate for the needle so that it does not perforate the palm skin.

Illustration 91: Block of the thumb and fingers.

Block of the Great Toe 29

1. Anatomical landmarks: Metatarsal bone of the great toe.

2. Patient positioning: Place the patient on his back with the sole of the foot in the PHCP’s hand and the top of the foot facing upward.

3. Procedure:

A. Raise an intradermal wheal at the dorsomedial border of the foot alongside the metatarsal bone, web of the great toe, and at the border of the metatarsal bone of the great toe (Ill. 92).

B. Advance the needle through the wheal and inject the anesthetic into the interosseous space. Repeat the injection in a fanwise manner along the interosseous space.

C. Introduce the needle through a wheal on the web and inject anesthetic in a fanwise manner.

D. Introduce the needle through the wheal at the border of the foot and inject in a direction beneath the metatarsal and also over it toward the midline of the foot.

4. Precautions: The PHCP’s hand should be on the sole of the patient’s foot so as to prevent penetration of the sole by the needle

Illustration 92: Block of the great toe.

Block of the Anterior Tibial Nerve 30

(Uses: Employed in conjunction with the posterior tibial nerve block for anesthesia of the foot. )

1. Anatomical landmarks: Internal malleolus and tendon of the tibialis anticus muscle.

2. Patient positioning: The patient is placed in a supine position with the leg flexed so that the sole of the foot rests upon a solid surface.

3. Procedure:

A. Mentally draw a line across the ankle that passes through the internal malleolus (Ill. 93).

B. Raise an intradermal wheal lateral to the tendon of the tibialis anticus.

C. Advance the needle through the wheal until it encounters the tibia.

D. Withdraw the needle approximately 2 mm and inject the anesthetic.

E. Withdraw the needle slightly and then reinsert it in a lateral direction between the extensor hallucus and the extensor digitorum longus tendon until the tibia is reached.

F. Inject the anesthetic.

4. Note: A garter band of subcutaneous infiltration should be introduced around the ankle.

Illustration 93: Block of the posterior and anterior tibial nerve.

Block of the Posterior Tibial Nerve 31 32

(Uses: This block is used in conjunction with an anterior tibial nerve block for anesthesia of the foot. )

1. Anatomical landmarks: The Achilles tendon and the internal malleolus of the tibia.

2. Patient positioning: The patient is placed in a prone position.

3. Procedure:

A. Locate base of the internal malleolus and mentally draw a line across the ankle that passes through its base (see Ill. 93).

B. Palpate the Achilles tendon and note its medial border.

C. Raise an intradermal wheal on the medial border of the tendon.

D. Advance the needle through the wheal perpendicularly to the skin towards the tibia.

E. Pass the needle through the deep fascia and fat until paresthesias are felt.

F. Inject the anesthetic.

Block of the External Popliteal Nerve 33

(Uses: For operations on the lower leg and foot.)

1. Anatomical landmarks: Head of the fibula at the lateral aspect of the leg.

2. Patient positioning: The patient is laid on his uninjured side, exposing the operative site.

3. Procedure:

A. The head of the fibula is palpated, then the depression just below it is located (Ill. 94).

B. An intradermal wheal is raised over the depression of the fibula.

C. Advance the needle through the peroneus muscle toward the bone.

D. Inject the anesthetic in a fanwise manner close to the bone. If paresthesias are elicited, all of the anesthetic can be injected in this one location.

4. Note: The external popliteal nerve block is used in conjunction with the internal popliteal nerve block and garter band infiltration below the knee.

Illustration 94: Block of the external and internal popliteal nerve.

Block of the Internal Popliteal Nerve 34 35

(Uses: For operations on the calf and foot.)

1. Anatomical landmarks: The angle formed by the semimembranosus muscle and biceps tendon at the superior border of the popliteal space.

2. Patient positioning: The patient is placed in a prone position.

3. Procedure:

A. Draw a mental line transversely across the bend of the knee in the popliteal space (see Ill. 94).

B. Mark off the angle formed by the muscles at the superior border of the popliteal space.

C. Bisect this angle with a ver tical line that runs through the popliteal space.

D. Raise an intradermal wheal on this line about 7 cm above the fold of the knee.

E. Pierce the deep fascia and inject anesthetic.

Block of the Femoral Cutaneous Nerve 36 37

(Uses: For superficial procedures upon the lateral aspect of the thigh.)

1. Anatomical landmarks: The anterior superior iliac spine and the inguinal ligament.

2. Patient positioning: The patient is placed on his back.

3. Procedure:

A. Raise an intradermal wheal 1 cm caudad and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (Ill.95).

B. Introduce the needle vertically through the wheal and advance it until the iliac bone is encountered.

Illustration 95: Block of the femoral cutaneous nerve.

C. Withdraw the needle slightly after having injected anesthetic at the bone and through the path to it.While withdrawing the needle, perform fanlike injections in the lateral and medial directions along the iliac spine.

Block of the Femoral Nerve 38 39

(Uses: For procedures on the anteromedial aspect of the thigh.)

1. Anatomical landmarks: The inguinal ligament and femoral artery.

2. Patient positioning: The patient is placed on his back.

3. Procedure:

A. Identify the inguinal ligament (Ill.96).

B. Palpate the femoral artery with the left index finger.

C. Raise an intradermal wheal just below the inguinal ligament lateral to the femoral artery.

D. Introduce the needle through the wheal perpendicular to the skin until the iliac fascia has been pierced.

E. Inject the anesthetic.

Illustration 96: Block of the femoral nerve.

1 John Keegan and Richard olmes,Soldiers (New York, NY: Viking, 1986), p. 148.

2 Thomas Clarke Kravis and Carmen Germaine Warner, Emergency Medicine (Rockville, MD: An Aspen Publication, 1983), p. 139.

3 Ronald D. Miller, Anesthesia (New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone Inc. , 1990), p. 1407.

4 Mark W. Wolcott, Ambulatory Surgery and the Basics of Emergency Surgical Care (Philadelphia, PA: L. B. Lippincott Company, 1981), p. 18.

5 James D.Hardy, Rhoads Textbook of Surgery Principles and Practice (Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1977), p. 50.

6 Parke-Davis, Ketalar (insert) (Morris Plains, NJ, 1990), p. 2.

7 Ibid. p. 4.

8 Ibid. p. 4.

9 Ibid. p. 4.

10 George J. Hill, Outpatient Surgery (Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Company, Inc., 1988), p.28.

11 David E. Longnecker and Frank L. Murphy, Dr ipps/ Echenhoff/Vandam Introduction to Anesethesia (Phila delphia PA: W.B. Saunders Company, Inc., 1992), p. 244.

12 Roger C. Good, Guide to Ambulatory Surgery (New York, NY: Grune and Stratton, Inc., 1982), p. 17.

13 Mark W. Wolcott, Ferguson’s Surgery of the Ambulatory Patient (Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company, Inc., 1974), p. 30.

14 Ibid. p. 30.

15 David E.Longnecker and Frank L. Murphy, Dr ipps/Echenhoff/Vandam Introduction to Anesthesia (Philadelphia, PA: W.B.Saunders Company, Inc., 1992), p. 244.

16 George J. Hill, Outpatient Surgery (Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Company, Inc. , 1988), p. 28.

17 Mark W. Wolcott, Ferguson’s Surgery of the Ambulatory Patient (Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company, Inc., 1974), p. 30.

18 David E.Longnecker and Frank L. Murphy, Dripps/ Echenhoff/Vandam Introduction to Anesthesia (Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company, Inc., 1992), p.244.

19 Steve Barnes, Personal Correspondence/October 1992.

20 Robert D. Dripps, James E. Echenhoff, and Leroy D. Vandam, Introduction to Anesthesia: The Principles of Safe Practice (Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company, Inc., 1982), p.252.

21 Ronald D. Miller, Anesthesia (New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, Inc., 1990), p. 1413.

22 Stuart C. Cullen and C. Philip Larson, Jr., Essentials of Anesthetic Practice (Chicago, IL: Medical Publishers, Inc., 1974), p.249.

23 Ibid., p. 249.

24 George J. Hill, Outpatient Surgery (Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Company, Inc., 1988), p. 29.

25 Robert D. Dripps, James E. Echenhoff, and Leroy D. Vandam, Introduction to Anesthesia: The Principles of Safe Practice (Philadelphia, PA: W.B.Saunders Company, Inc., 1982), p. 242.

26 Stuart C. Cullen and C. Philip Larson, Jr., Essentials of Anesthetic Practice (Chicago, IL: Medical Publishers, Inc., 1974), p. 256.

27 John Adriani, Techniques and Procedures of Anesthesia (Springfield, IL: Thomas Books, 1947), p. 299.

28 Vincent J. Collins, Pr inciples of Anesthesiology (Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger, 1976), p.> 982.

29 John Adriani, Techniques and Procedures of Anesthesia (Springfield, IL: Thomas Books, 1947), pp. 310-311.

30 Ibid. pp. 309-310.

31 Ibid. pp. 308-309.

32 Ronald D. Miller, Anesthesia (New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, Inc., 1990), p. 1423.

33 John Adriani, Techniques and Procedures of Anesthesia (Springfield, IL: Thomas Books, 1947), p. 306.

34 Ibid. pp. 306-307.

35 Vincent J. Collins, Pr inciples of Anesthesiology (Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger, 1976), p. 999.

36 John Adriani, Techniques and Procedures of Anesthesia ( Springfield, IL: Thomas Books, 1947), pp. 302-303.

37 Vincent J. Collins, Pr inciples of Anesthesiology (Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger, 1976), p. 986.

38 John Adriani, Techniques and Procedures of Anesthesia (Springfield, IL: Thomas Books: 1947), pp. 301-302.

39 Robert D. Dripps, James E. Echenhoff, and Leroy D. Vandam, Introduction to Anesthesia: The Principles of Safe Practice (Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company, Inc., 1982), pp. 246-247.