With the introduction of gunpowder and the missiles it propels to the battlefield, the amputation of mangled limbs became a routine wartime surgical procedure. Early amputations were not known for their success. A Londoner from the 1700s is quoted as having said, “Amputation is an operation terrible to bear, horrid to see, and must leave the person on whom it has been performed in a mutilated imperfect state.” 1 During this time, a surgeon’s proficiency was based upon how long it took him to remove a limb. A surgeon who took as long as three to four minutes for the amputation earned himself a “shameful distinction.” 2This emphasis on time inevitably led to unnecessary trauma to the tissues, with the consequences of infection, lethal hemorrhage, or, at best, a persistently draining stump that healed poorly, if at all.

The more enlightened surgeons practiced careful handling of tissues and the precise placement of ligatures. This approach resulted in leaving healthier tissue and thus a quicker and less complicated recovery. Of course, such diligence took longer than four minutes. For military surgeons who were confronted with “dirtier” wounds than those found in civilian patients, an amputation technique that allowed the stump adequate drainage and at the same time did not require an unusually high degree of technical skill was felt to be the safest approach to take.

The open circular amputation first described by Bell in 1788 became the amputation technique of choice for the wound suffered in a combat theater (sometimes referred to as the “guillotine amputation”). 3 4 5The use of the open circular amputation in military theater hospitals became written policy for the U.S.Army on April 26, 1943, when Major General Norman Kirk issued the directive in War Department Circular Letter 91.6 After evaluation of the casualties from the African campaign, Kirk found that patients in whom an amputation was left open, properly drained, and healed by granulation recovered more quickly and with fewer fatalities than those who had their amputated stumps closed early with a flap of skin.

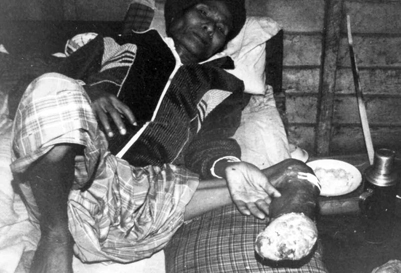

It is quite likely that the PHCP will be called upon to render aid to the soldier who has suffered a traumaticamputation from a land mine or high-velocity rounds.Mud, grass, and fragments of the mine will be driven into what tissues are left. If the soldier does not die from blood loss, his mangled limb has now become a fertile ground for infection. An open circular amputation performed on this casualty can be a life-saving emergency procedure, given the parameters in which the PHCP must carry out medical treatment 7 (Photo 71).

Photo 71: This 57-year-old Burmese patient lost his left foot after having stepped on a land mine. It took six days of arduous transport to reach a dispensary. The patient was a prime candidate for an open circular amputation. However, resources for such a procedure were not available. The patient is left with a gaping, inflamed wound. (Photo courtesy of Hugh Wood.)

INDICATIONS FOR AN AMPUTATION8

1. Trauma to the extremity: The patient in this case has suffered extensive trauma to an extremity. The limb has been blown, torn off, or so mangled that it has obviously become nonviable (Photo 72). In this situation, the PHCP’s function is a simple revision of an amputation that has already occurred.

Photo 72: Amputation of both lower legs due to blunt trauma. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Gerald Gowitt.)

2. Vascular insufficiency: The patient may have been wounded in such a manner that major blood vessels have been destroyed (Ill. 97). Portions of the extremity distal to the interrupted blood flow can quickly develop nutritional deficit, leading to the development of ischemic gangrene.

Illustration 97: Gangrene of foot and leg due to a damaged femoral artery (vascular insufficiency) resulted in the need for amputation of this leg.

3. Infection: Amputation of extremities suffering from massive gas gangrene or other types of infection can be lifesaving in a field setting where antibiotics are either not available or have not been effective. Also, in an effort to remove tissue that had become necrotic due to extensive infection, debridement may have left an extremity damaged beyond hope of function.

DETERMINING THE EXTENT OF AMPUTATION

Determining the level at which an amputation should take place will not only have an immediate effect upon the ability of the stump to heal properly, it will also have a longterm effect upon the ability of the patient to be receptive to prosthetics. Traumatic wounds from things such as land mine explosions impart terrific impact forces to tissues.These impact forces can travel along muscle groups well above the sight of the traumatic amputation and result in devitalized tissues. Studies have shown that the type of footware worn by the soldier at the time of the mine explosion is a determining factor in how these impact forces are trans ferred to the leg. The need for an above the knee (AK = above the knee amputation/BK = below the knee amputation) surgical amputation due to mine-related injuries in Thailand was 100 percent if boots were worn, but only 29 percent if sandals or shoes were worn. 9

These devitalized tissues, if not properly identified, may be left intact after the surgical amputation. Gas gangrene could then develop in the stump. Every effort is made to save knees and elbows and to leave as much bone and tissue length as possible. It is easier for the patient to be rehabilitated when a prosthetic is used in conjunction with a functioning joint.Also, the PHCP must keep in mind that he will be performing an open circular amputation only as a life-saving measure. It is a procedure that, in essence, is used to turn a contaminated, traumatic amputation into a clean, surgical amputation. This “clean” surgical amputation is often revised or amputated again at a slightly higher level with an amputation technique using flaps of skin to cover the stump as well as early stump closure by suture.

Presuming the patient may undergo later stump revision or “staged amputation” in a hospital, the PHCP in the field must be careful to leave as much viable tissue and bone as possible. 10The appropriate level of amputation is the most distal level at which healthy tissue is found, given that it is fed by an intact arterial system. The incision is made through this healthy tissue proximal to the damaged tissues. It is not always easy to ascertain the true lowest level of viable tissue in a traumatic amputation. As one orthopedic team in the Mediterranean Theater reported, “‘Where to amputate’ sounded simple when it was followed by the statement ‘At the lowest possible level.’” 11

DETERMINING CIRCULATORY STATUS

IN THE INJURED LIMB

As stated, determining whether there is proper blood flow to the wounded extremity is a fundamental question to be answered. Tests that would assist the PHCP in determining the extent of circulation and at the same time be applicable for field use are temperature of the skin, color of the skin, and condition of arteries. 12 However, these are rough measures and not sole determinants.

Temperature of the Skin

The line of temperature demarcation between the warm, well-supplied tissues and the cool, deprived areas of the extremity provide a general indication of where tissue is in the process of dying or has died due to poor blood circulation.With no instruments to measure where serious arterial deficiency begins, the PHCP will have to rely on his hand to sense the changes in temperature. Use of the hand can only be expected to give a broad indication of actual skin temperature.

To help accentuate the line of temperature demarcation, the PHCP can expose both the wounded and uninjured leg to room temperature for 15 to 20 minutes. The portions of the wounded limb that are suffering arterial flow insufficiency will become cool in comparison to the uninjured limb and “supplied” portions of the wounded limb. Next, both limbs are covered with blankets for another 15 to 20 minutes. Once the blankets are removed, the deprived portions of the limb will have failed to warm up with the rest of the extremity. As a rule, the PHCP should not perform an amputation below the line of established temperature demarcation. 13

Color of the Skin

A patient who has suffered a traumatic wound may quite naturally have a pale appearance due to shock. However, an area deficient in arterial blood supply will usually have a cadaveric pallor. The PHCP can carry out further evaluation by pressing his finger firmly against the extremity in question.When the arterial flow to the area pressed is sufficient, the pallor produced by the pressure should be replaced with normal skin color just a few seconds after the PHCP removes his finger.Conversely, an extremity suffering from poor circulation will retain its pallor for many seconds.

The PHCP can also elevate the wounded leg and foot. If it is suffering from arterial deficiency, the limb will become very pale. When the limb is lowered, the foot may become red or purplish. It is generally advised that if this deep blush is present very far past the foot, amputation below the knee is not advisable. 14

Condition of the Arteries

The presence of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulse in the foot are important signs of sufficient arterial flow to the distal portions of the leg. The status of collateral circulation in the injured limb is of importance, but the absence of a popliteal pulse is an indication that amputation below the knee is seldom safe. 15 For wounds to the arm, the integrity of the radial pulse in the wrist would need to be evaluated.

The results of these test are rough measures of arterial blood flow. The PHCP would do well to employ all of these tests as he tries to determine where arterial circulation has come to an end.Even in a best-case situation, this determination in the field may be difficult. The PHCP could be forced to settle for an amputation site higher than he would like. The PHCP must not overlook the fact that dislocations and fractures of limbs or pressure from bandages, splints, or swelling can impede blood flow and therefore must be investigated thoroughly.

TECHNIQUE FOR AN ABOVE THE KNEE

OPEN CIRCULAR AMPUTATION 16 17 18 19 20

1. The limb is draped so the PHCP has circumferential access to all portions of the thigh. If practical, the thigh is elevated during the amputation to save as much distal venous blood as possible.

2. A tourniquet is applied. It can be removed at that point in the procedure when major vessels have been ligated and bleeding controlled.

3. An assistant places his hands on the thigh above the intended amputation site and pulls on the skin in the direction of the hip. The PHCP holds the amputation knife firmly in his hand and starts the incision at the side of the extremity opposite to where he stands. A circumferential incision is made through the skin and the skin is allowed to retract. The position of the knife is changed as needed (Ill. 98).

Illustration 98: A circumferential incision is being made above the knee. This incision begins an amputation that is needed due to a traumatic amputation of the lower leg.

4. The fascia is then circumferentially incised at the level to which the skin has retracted.

5. The superficial layer of muscle is cut at the end of the fascia and allowed to retract.

6. Once the superficial layer of muscle has retracted, the deep layers of muscle are circumferentially incised at the point where the superficial muscle has retracted. Blood vessels are clamped and ligated as they are encountered. Major arterial stumps receive double ligation.

7. Upward pressure is now placed on the proximal muscle stump with gauze or amputation shield. This upward movement of the muscle stump in combination with the natural retraction that is characteristic of incised muscle tissue will help ensure that the end of the transected femur will rest several centimeters proximal to the muscle stump once the muscle is allowed to return to its natural position.

8. After the deep muscles have been retracted, the periosteum of the bone is incised and the femur sawn through flush with the retracted muscles, just slightly distal to the periosteum incision site. The femur end should remain covered with periosteum, as bone denuded of periosteum often will sequestrate if infection develops. Care must be taken not to elevate or tear the periosteum by rough handling.

Illustration 99: Transection of the femur. Note the use of an amputation shield and irrigation during the procedure.

9. When the bone is being sawn through, it should be irrigated with Normal Saline solution to protect it from the heat generated by the sawing (Ill. 99). Major nerve stumps are pulled forward by forceps and cut at the uppermost level that can be reached. Occasionally they must be ligated due to bleeding. Drainage from the femur can be controlled with bone wax or gauze.

Once the amputation has been completed, the stump should be concave in appearance. The femur end should be shorter than the muscles and the muscles shorter than the skin (Ills. 100 and 101).

Illustration 100: Note proper concave appearance of the stump and the convex appearance of the discarded limb.

Illustration 101: Final ligation of a persistent bleeder. Note ligated major vessels close to the femur.

POST-PROCEDURE STUMP CARE

Once the amputation has been completed, the recess of the stump is packed loosely with gauze. This recess packing is applied so the gauze does not overlap the skin edges. A layer of protective gauze is now placed over the recess packing. The gauze is changed as needed, with special attention given to sterile technique during dressing changes.

Following the amputation, the prevention of skin retraction on the stump is absolutely essential. Along with the development of infection and massive hemorrhage, skin retraction is a serious complication. As the wound heals, the skin will retract and expose muscle and bone if traction to the skin is not applied. Obviously, the stump can never heal properly with muscle and bone exposed.

Traction upon the skin of the leg stump can be accomplished by placing adhesive tape on all four sides of the stump. This tape is then fashioned into strips that, in combination with a Thomas splint and additional tape or Ace bandages as deemed necessary, can be used to apply traction. The Thomas splint is only applicable for maintaining traction on the leg and is somewhat awkward to apply and easily mispositioned during patient transport.

It was found during World War II that, when possible, traction was better maintained by the use of a light plaster cast and built-in wire ladder splint. 21The cast was formed over a stockinette that was “glued” to the skin of the stump. The ends of the stockinette were then run to the wire ladder splint, where traction could then be applied (Ills. 102 and 103). The cast was always designed to include the joint above the amputation.

Illustration 102: Use of a light cast, stockinette, and wire ladder splint to maintain traction on an arm stump.

Illustration 103: Use of a light cast, stockinette, and wire ladder splint to maintain traction on a leg stump.

The PHCP’s most difficult task is not so much the actual application of the traction device but the prevention of slippage.In rainy, humid environments, the traction tapes cannot be expected to hold long. Joseph Serletti’s technique for the use of tincture of benzoin, Ace wraps, and stockinette is an approach that will not result in slippage as readily as tape. 22

The tincture of benzoin is applied to the skin of the stump about 1 inch proximal to the end of the stump. It is also applied to the groin area, abdomen, umbilicus, and the lateral and posterior aspects of the spine. A 6-inch stockinette is applied over the stump up to the point of the lowest rib. The stockinette will have to be split to a degree down its sides to reach the rib. The tincture of benzoin is given a moment to adhere to the stockinette. Ace wraps are now used around the body, hip, and stump to further anchor the stockinette.

Care must always be taken with constrictive wrapping not to restrict blood flow, particularly around joints. The portion of the stockinette that falls below the stump is split along its sides up to the stump end to gain access for dressing changes.The ends of the stockinette are tied together and then tied to a length of rope. The rope is run over the bed through a pulley and weighted down with about 5 to 6 pounds to achieve traction (Ill. 104). 23 24 25

Illustration 104: Use of Ace wraps, stockinette, and weighted pully system to maintain traction on a leg stump.

An acceptable traction arrangement is one that will not slip over a course of several days of usage. It also allows easy access for dressing changes of the stump, can be reapplied easily, and can be mated with 5 to 6 pounds of weight. Even the best traction devices will need replacing periodically due to slippage. The ability of the patient to maintain personal hygiene must not be overlooked, since patients who have undergone an open circular amputation can remain in traction for several weeks.

CLOSURE OF THE STUMP FOLLOWING AN OPEN

CIRCULAR AMPUTATION

Stump closure is generally carried out by one of three techniques. The stump may be allowed to simply granulate (scar) over, the skin of the stump end may be undermined enough at its edges to allow closure by suture, or the stump can undergo reamputation with an amputation technique that incorporates the use of skin flaps and early closure. It is best for the PHCP to restrict himself to the use of traction and granulation for stump closure.

When the stump is simply allowed to granulate over, continued traction is the key to success. In a “best case” scenario, continued traction will result in secondary intention skin closure over the stump (Ill. 105). Effective traction allows growing tissue to be held in place for the formation of scar tissue.Healing by granulation takes the longest of all approaches to bring about stump closure. It is not unusual for the patient to remain in traction for 14 weeks. 26

An open circular amputation that is left to heal by granulation is often criticized for the large scar left, long healing period, muscle retraction, exposure of bone, prolonged drainage, scar adherence to bone, and reinfection. These complications usually can be avoided with proper traction and wound maintenance of the stump. Although there are shortcomings with closure of the stump by granulation, it is still the best approach for the PHCP in a forward care area to take.

The open circular amputation is often thought of as a temporary “fire break” procedure against infection that, in many cases, is expected to undergo secondary amputation to effect final repair of the stump. The PHCP would have well served his patient when, after extended transport, the wounded soldier is delivered to the hospital-based surgeon with a stump as long as possible, not infected, and in advanced stages of healing. Proper traction and careful attention to maintaining a clean, well-drained stump should accomplish these goals.

Illustration 105: Continued skin traction has resulted in partial closure of the stump by secondary intention.

A CASE STUDY

This 22-year-old laborer suffered a crushing blow to his left index finger while fitting pipe. The end of the finger was severed through the bone, leaving only a small flap of skin that connected the mangled fingertip.

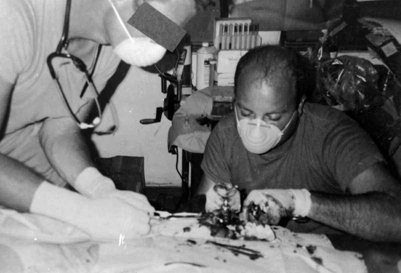

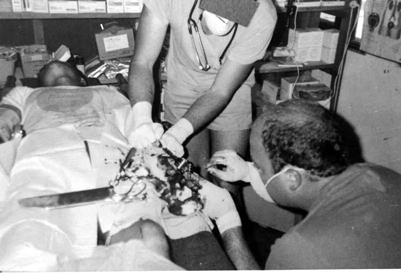

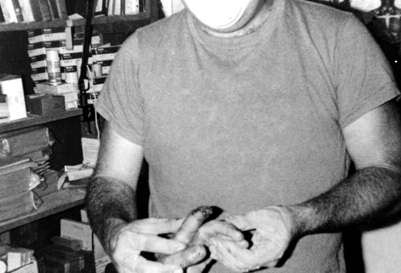

The patient arrived at a makeshift clinic within 10 minutes of the injury. The finger was anesthetized with Lidocaine employed as a regional nerve block. The finger was thoroughly cleaned in Betadine. Once it was established that it was not possible to reattach the fingertip, a surgical amputation site was chosen. The PHCP elected to fashion a skin flap which he used to close the finger. The patient was placed on oral antibiotics and the finger healed without complications (Photos 73 through 76).

Photo 73: While the lead PHCP is determining whether his regional nerve block has been successful, his assistant is monitoring the patient’s blood pressure. (Photo courtesy of Glenn Dorner.)

Photo 74: With the assistant using retractors to expose the viable bone, the lead PHCP uses a bone saw to remove crushed bone. (Photo courtesy of Glenn Dorner.)

Photo 75: With retractors still in place, a bone rasp is being used to ensure no bone spurs are left. Note bone saw laying across the patient’s legs. (Photo courtesy of Glenn Dorner.)

Photo 76: A skin flap has been fashioned and used to close the end of the finger. (Photo courtesy of Glenn Dorner.)

NOTES

1 Warren H. Cole and Robert Elman, Textbook of General Surgery (New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1948), p. 246.

2 Ibid. p. 246.

3 M.C. Wilber, L.V. Willett, Jr., and F. Buono, “Combat Amputees,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 1970, p. 10.

4 Henry H. Kessler, “Amputation Lessons From The War,” American Journal of Surgery, 1947, p. 309.

5 Emergency War Surgery (Fuller ton, CA: S.E.A. Publications, 1982), p. 240.

6 M.C. Wilber, L.V. Willett, Jr., and F. Buono, “Combat Amputees,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 1970, p. 11.

7 Kenneth L. Mattox, Ernest Eugene Moore, and David V. Feliciano, Trauma (San Mateo, CA: Appleton and Lange, 1988), p. 786.

8 Oscar P. Hampton, Surgery in World War II: Orthopedic Surgery Mediter ranean, Theater of Operations (Medical Department, United States Army, 1957), pp. 246-247.

9 L. William Traverso, Arthur Fleming, David E. Johnson, and B. Wongrukmitr, “Combat Casualties in Nor thern Thailand: Emphasis on Land Mine Injuries and Levels of Amputation,” Military Medicine, 1981, p. 683.

10 Daniel F. Fisher, Jr., G. Patrick Clagett, Richard E. Fry, Theodore H. Humble, and William J. Fry, “One-stage versus two-stage amputation for wet gangrene of the lower extremity: A randomized study,” Journal of Vascular Surgery, 1988, p. 428.

11 Oscar P. Hampton, Surgery in World War II: Orthopedic Surgery, Mediter ranean Theater of Operations (Medical Department, United States Army, 1957), p. 249.

12 Warren H. Cole and Robert Elman, Textbook of General Surgery (New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1948), p. 254.

13 Ibid. p. 254.

14 Ibid. p. 254.

15 Ibid. p. 254.

16 U.S. Army Special Forces Medical Handbook (Boulder, Colorado: Paladin Press, 1982), pp. 16.5-16.6.

17 Oscar P. Hampton,Surgery in World War II: Orthopedic Surgery, Mediter ranean Theater of Operations (Medical Department, United States Army, 1957), p. 251.

18 Horst-Eberhard Grewe and Karl Kremer, Atlas of Surgical Operation (Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunder s Company, 1980), pp. 426-428.

19 J.S. Speed and Hugh Smith, Campbell’s Operative Orthopedics (St. Louis, MO: The C.V. Mosby Company, 1939), p. 831.

20 Warren H. Cole and Robert Elman, Textbook of General Surgery (New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1948), pp. 257-258.

21 Oscar P. Hampton, Surgery in World War II: Orthopedic Surgery, Mediter ranean Theater of Operations (Medical Department, United States Army, 1957), p. 254.

22 Joseph C. Serletti, “An Effective Method of Skin Traction in A-K Guillotine Amputation,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 1981, pp. 213-214.

23 Ibid. p. 214.

24 Emergency War Surgery (Fuller ton, CA: S.E.A.

Publications, 1982), p. 242.

25 U.S. Army Special Forces Medical Handbook (Boulder, Colorado: Paladin Press, 1982), p. 16.6.

26 Joseph C. Serletti, “An Effective Method of Skin Traction in A-K Guillotine Amputation,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 1981, p. 212.