The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.

—FRIEDRICH VON HAYEK

I’m only rich because I know when I’m wrong.

—GEORGE SOROS

Big Questions

GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT (GDP) reflects the sales of businesses throughout the economy, which indicates the direction of their earnings, which are related to their stock prices—but macroeconomics is shockingly ineffective in predicting the stock market. New economic data are released daily, which tends to shorten our horizons. More critically, the links between different big-picture numbers, specific companies, and stock prices are weak, dynamic, and often poorly understood. Data report the past; stock prices reflect future expectations. The chain of intermittent connections makes it hard to spot where we went wrong, or even know that we erred. Most economic forecasts are meant to suggest the trend of stock prices but never pause to estimate their fair value.

Beyond intellectual curiosity, the siren call of big-picture investing is that it looks easy, because a deluge of pertinent information arrives daily in the news. It might even appear that macro inquiry takes less research than specific stocks. Furthermore, the value of perfect foresight of changes in GDP or the S&P 500 would be gargantuan compared to foresight about an individual stock. Macro investors deal in massive, liquid markets, so there’s never a worry about quickly entering (or exiting) a position of the desired size. Positions can be scaled up, because margin requirements for futures and derivatives based on stock indexes, bonds, commodities, and foreign currencies are minuscule compared with individual stocks. Selling short is no hassle in derivative markets, unlike stocks.

While most investors using a top-down approach make a hash of investing, a few have made spectacular fortunes with big-picture decisions. Roger Babson correctly called the 1929 stock market crash and left a fortune to endow Babson College. George Soros and John Paulson made billions shorting the British pound and subprime mortgages, respectively. When I was younger, I was convinced that macro mavens must have a great universal theory of everything economic in their heads. I now believe that their common features are first, openness to contradictory information; second, some way of testing whether they are incorrect; and third, a willingness to change their minds.

Almost from the start, economists have conceived of the economy as a machine. The economist William Phillips built a sculpture of the economic machine, which he called MONIAC. My grandfather William had an amazing talent for taking cars apart and reassembling them in working order. Once, I wanted to do the same thing with the economy. But I doubt that I can take apart the economy, let alone reassemble it.

Here’s the problem: Every one of the parts in economics is abstract. What constitutes the economy or the market, or any piece of it, depends on your definitions. The “market” could be defined as all of the four thousand or so stocks listed in the United States, or just the five hundred in the S&P’s 500, or the thirty in the Dow Jones Industrials. Is the economy made up of just the companies in a stock index? Shouldn’t private companies and other organizations count as well, not to mention the self-employed?

Change definitions, and you change numbers. During the global financial crisis in 2009, some European countries struggled to meet targets for national debt based on GDP. By changing the definition to include revenues from prostitution, illicit drugs, and other activities, reported GDP was boosted by a couple of percentage points. With economic knowledge built on such abstract, shifting definitions, the idea of a perfect model with perfect foresight seems laughable.

During the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes wrote The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, the most famous book ever written on macroeconomics. This theory is what most universities teach and many governments practice. While Keynesian theory has defects, there aren’t yet any coherent, comprehensive alternatives, leaving open the question of whether it is better to be guided in error or unguided. Keynes created most of the key definitions used in macroeconomics, such as GDP equals consumption, capital investment, and government spending, plus exports minus imports.

The most volatile component, which often leads the other components and usually triggers booms and recessions, is capital investment. Businesses need to build capacity only when demand is growing. If demand tumbles, businesses won’t add plant capacity and often don’t even replace worn-out equipment. When businesses decide to invest, they have to consider the profits over the entire life of the equipment, not just the year ahead. But future profits are only projections, not yet facts. Therefore, investment depends on businesspeople’s general outlook, which Keynes called “animal spirits.” Forecasts will be wrong because animal spirits are elevated or depressed. Keynes’s model sounds more like a living thing than a machine.

People forecast for many reasons other than to accurately predict the future; on Wall Street, estimates are primarily used to sell something and never look back. For example, a projection that Internet currencies will be widely accepted may be meant to spur actions to cause this forecast to come true. Conversely, Al Gore admitted that his forecast of global warming was meant to prompt action to avert disaster. Keynes’s model was intended to influence government policy more than to make predictions. When animal spirits were low, his forecast was that the economy fared better if governments ran larger budget deficits. Governments have acted accordingly.

The economist Milton Friedman claimed that economic models need not use assumptions that look anything like the real world; they need only predict accurately. Really? Scientists start by observing and describing everything as precisely as possible, especially how pieces fit together into systems. Then they develop a model to explain things. They don’t (and can’t) make predictions until they can explain what’s going on. Although physicists often begin with simple models and ideal assumptions that they know are unrealistic, they later add back the frictions and complexity that they had earlier ignored.

Importantly, physics models actually have to predict accurately; economics has lower standards of proof. When testing his general theory of relativity, Albert Einstein said, “If a single one of the conclusions from it proves wrong, it must be given up.” Just one counterexample is enough to show a scientific theory is invalid. Economists don’t work that way. If they did, nothing would be left of macroeconomics. Show me a model with ridiculous assumptions that predicts perfectly, and I’ll accept ridiculous assumptions.

Everything in economics and investing is tendencies, probabilities, and situations; nothing is everywhere and always. Most economic events reflect a long chain of events and probabilities. The only way I can follow that chain is to be as accurate and precise as possible in describing reality and start with realistic assumptions. Economic theories that describe simple actions and transactions are usually more reliable than those that describe complex systems. Even robust theories have counterexamples, so economists cling to theories with dreadful predictive records, unable to prove their validity either way.

When explaining stock prices through macroeconomics, the thread is often lost. Economic logic reminds me of the childhood game of telephone, in which a statement as simple as “Miss Du Bois planted a geranium near her house” could be twisted into something as unlike as “I saw Mr. Shapiro and Miss Du Bois smooching in her yard.” Similarly, there’s distortion and slippage with every link in a chain of economic and financial events. Often the end result is totally different from the starting point, especially because some economic actors are thinking short-term and others long-term. Investors have to imagine the many possible stories that could happen, not just the one that actually will.

Wassily Leontief’s GDP input-output model is the most precise model of a complex economy that I know of. The input-output matrix catalogs all of the inputs needed to produce everything the economy makes. Suppose an average auto uses 2,400 pounds of steel, 325 pounds of aluminum, and so on. The equipment to make the car might require another 600 pounds of steel per car. Based on auto production of 16 million vehicles, you could calculate how many millions of tons of iron ore would be needed. Predicting GDP should be a breeze, right?

But business economists don’t forecast GDP with an input-output model. The things the economy produces change constantly. Businesses will always look for ways to produce the same output with fewer inputs, and new products with old inputs. The input-output model works poorly for knowledge industries such as software, movies, or pharmaceuticals, where the bottlenecks and costs are in developing the first copy. Additional copies are cheap to make. With most economic growth now coming from knowledge industries, the input-output model has become a lousy way to estimate GDP growth. (Don’t write the model off entirely, though; the advent of Big Data may give it new life.)

Working at Drexel

When I worked as a research economist at Drexel Burnham Lambert in the 1980s, clients had no use for elaborate models or theories of everything. They simply wanted to know “the number” before a key economic statistic was reported or, failing that, explanations of what just happened.

We never looked very far, or very boldly, into the future. Traders played the statistics to be reported in the next month or quarter. Nailing the number was a favorite pastime, then and now. When my boss, Dr. Norman Mains, assigned me coverage of economic statistics, he advised me never to give a number and a date at the same time. I think he was joking, but his point was that frequently released numbers reflect a lot of noise, and there’s a lot we can’t know. Some economic policy makers and investors believe they can predict and control near-term events, while others aim for generally favorable long-term outcomes, accepting randomness or even pain in the interim.

To make guesses on economic statistics that weren’t too wide of the mark, I had to learn how the sausage is made. Many statistics are calculated with data that have already been released, adding some new information. Industrial production numbers feed into the calculation of GDP growth but are released earlier, giving a hint of the latter number. The government uses electric power consumption to estimate industrial production. Heating and cooling degree-days can be calculated before the electricity consumption numbers are released. When it was very hot or cold, more electricity would be used. But with every step, there’s some slippage, so you can’t leap from degree-days to GDP growth, let alone market impact.

I could make a decent stab at monthly figures by taking the average change over the last year. When consumer prices had been up an average of 0.2 percent a month, my estimate might be 0.2 percent. If earnings per share had risen 10 percent over the last year and the year ago quarterly earnings per share was 50 cents, my forecast was 55 cents. Sometimes there would be flaky data or unusual events in a period, and I would tweak the numbers a bit. I’d also adjust for the components that had already been reported. To make sure I hadn’t missed something, I would check out other economists’ predictions.

Eventually, Dr. Mains encouraged me to share my predictions with journalists and clients, but one customer told me he never read my daily comments because he couldn’t make money from them. My forecasts were accurate enough, he told me, but they were copycats of everyone else’s. The client only cared about the size of the market reaction, not the data itself, so consensus forecasts and minor statistics like capacity utilization were distractions. A correct prediction also had to be important and unexpected. The client was a fan of economists with forceful views and a persistent tilt that happened to match his own. Economists don’t forecast because they want to, but because they are asked.

High Taxes = Strong Economy?

My most frustrating project at Drexel was attempting to show that President Reagan’s tax cuts had been a great boon to the economy. Many clients and all of the senior people at Drexel were in the top income tax bracket, so the desired conclusion was self-evident. Even though I was far from the top bracket and wary of the intersection of economics and political beliefs, I believed the answer that we favored was actually correct. Most economists will tell you that lower taxes cause people to work harder because they keep more of what they produce.

Higher taxes reduce the incentive to work, which should slow GDP growth, but the data weren’t cooperating. I tabulated all the years in which the top marginal tax bracket was greater than 80 percent. In 1941 the top bracket was raised to 81 percent, in 1942 to 88 percent, to 94 percent in 1944, and then trimmed to 91 percent in 1946, where it remained until 1964, when it was reduced to 77 percent. Over that twenty-three-year period, real GDP grew from $1.27 trillion to $3.59 trillion in 2009 dollars, or a 4.6 percent compounded growth rate. Those were actually among the strongest growth rates since the United States has kept reliable statistics.

To explain a vigorous economy with high taxes, I needed a different story. When the United States was coming out of the Great Depression, many people were barely getting by. Increased taxes might have forced people to work more to keep up their standard of living. Pitching in for the war effort was considered a patriotic duty. Because this annoying evidence was a few decades in the past, no one cared about it.

Between 1981 and 1990, the top tax bracket was chopped from 70 percent to 28 percent. During that stretch, real GDP growth was 3.4 percent a year, also above average, but not as much. If you were determined to show the benefits of lower tax rates, you’d compare the period between 1981 and 1990 against the previous nine years, which had been abysmal, but that might not be a fair comparison. Oil prices had jumped between 1972 and 1981, and fallen back in the Reagan years. Interest rates had spiked to unprecedented levels by 1981 and then reverted back. In the earlier period, the unpopular Vietnam war had wound down, and Richard Nixon became the only American president ever to resign from office.

The Reagan tax cuts were intended to be a straightforward case, and I wondered whether it was possible to use economics to invest intelligently when causation is so hard to trace. In economics, all else is never equal. You can’t look at one factor in isolation. There are depressions, wars, inspiring leaders, oil price surges, and crashes. Innovations are discovered in clusters, not neatly scheduled at appointed times. Every economic action has indirect effects and antecedents that you don’t immediately see. Often it’s nearly impossible to figure out even the direct effects. Statistics move together, like tax rates and GDP growth between 1941 and 1964, but that doesn’t tell you what caused what; correlation doesn’t prove causation.

Trading on Economics

At Drexel, the obvious way to show that my judgments had a market value was to trade.

Investors and traders aim to strike a delicate balance—accepting new information but not getting lost in redundancy, and being neither over- nor underconfident in the truth of their facts and logic. Then, I could be fleetingly brash about things of which I knew little, reflecting youthful bravado more than anything else, leaving me to blow with the winds as news reports arrived. In the end, my risk posture was dictated by circumstances. While working at Drexel, I was finishing my second year of business school. My tiny bank balance was more than offset by tuition bills, not to mention large student loans, so I had to start small, with one futures contract.

By putting down a small deposit of perhaps $1,500, I was able to “control” a $1 million Treasury bill contract or a $100,000 Treasury bond contract; the balance was implicitly borrowed. Dozens of other types of futures traded, but I couldn’t apply my knowledge as a research economist to them. If the value of the Treasury bond changed by a point—that is 1 percent of par—the contract would gain or lose $1,000. Every day, based on price movements, winnings or losses are settled in cash. If you are offside, you can lose your initial margin in a day or two. If you are right, your money multiplies quickly.

Every day, I could feel the economy getting stronger. In January 1983, the unemployment rate had been 11.4 percent. By May, it had plunged to 9.8 percent, and by December, 8.0 percent. I was absolutely rooting for a buoyant employment picture, which would also bolster stocks. But usually when the economy is galloping, interest rates rise as bondholders fret about inflation. A big part of Drexel’s futures business came from hedgers who were trying to protect against rising interest rates. A jump in rates, or even just worries, would bring in more hedging business. Everything I wished for fit together as a worldview.

I was convinced that a rebounding economy meant interest rates definitely had to go back up, so that’s how I bet in the futures market. For about three months, everything worked magnificently. Soon I had made enough to add another contract and another and so on. Sometimes I would do pairs of contracts, such as long Treasury bills and short certificates of deposit. The margin requirement for these “spreads” was less than for either contract individually.

For those three months, I was sure I had the magic touch. I decided to speculate with conviction. I pyramided my winning positions as they moved in my favor. Like alcohol, financial leverage can induce overoptimism and overconfidence. Once I had accumulated twenty-five contracts, and realized that every flicker might make me $625 richer or poorer, the screens hypnotized me. Just three ticks in my favor would throw off more than enough cash to add another contract. The profits gushed in so much more quickly than with stocks. Over a dozen weeks, I had collected more than $40,000, which exceeded my annual pay. I fancied launching a brilliant career as a trader.

In under a month, it all went splat. The economy kept growing vigorously, but inflation inexplicably slowed and interest rates tumbled more rapidly than they had risen. Other than the fact that I had lost money, I had no way to tell whether I was right or wrong, or to pinpoint the source of my mistakes. Some of the statistics had to be flukes. Maybe I hadn’t focused enough on the right economic statistics. Maybe I had simply missed something. My personal account, final exams, the Chartered Financial Analyst test, and my job were all wrangling for my attention.

My forty grand in winnings vanished faster than they had appeared. The margin clerk was visibly alarmed to note my cash balance of zero and that my positions had a hypothetical value of hundreds of times my annual income. I told him that was all I had, keeping silent about my student loans and bills. He sold out my account.

Stocks Anticipate

The margin call also blew apart my efforts to develop a stock market timing system. I had dabbled in stock index futures; but having lost all my play money and more, I had to stop. My goal was to connect economic statistics with interest rates, then link interest rates with stock indexes, then maybe stock indexes with specific stocks. I had figured out how some economic statistics tied in with other data, but simply could not connect economic data, interest rates, the stock market, and ultimately, trading profits.

Most investors assume that fluctuations in the economy tell you what the stock market will do, but they have it backwards. The stock market tells you what the economy will do. The Conference Board compiles an index of leading indicators that is meant to turn up or down before the broad economy. Of the ten leading indicators in the index, the most consistently effective one is the S&P 500 stock index. Investors look ahead a bit further than purchasing managers, for example. Arguably, slumping stock markets depress animal spirits and cause recessions.

Because economic statistics affect interest rates, many investors try to predict stocks by way of interest rates. Sometimes stock and bond prices move up or down together, and sometimes they go in opposite directions. When interest rates are rising and bond prices are falling, the economy and profits are usually advancing. Which matters more, interest rates or profits? It all depends.

Investors who focus on levels of interest rates will reach different conclusions from those who watch the changes in rates. Most investors assume a drop in interest rates will lift the economy and profits, and justify higher price/earnings ratios (P/Es). All of that is positive for stock prices. But it turns out that when inflation-adjusted interest rates are very low, returns on other financial assets are quite poor as well.

In the long run, stock prices reflect earnings, so many market-timers watch corporate profits. Again, some watch the levels of profits over time; others watch the rate of change. Most market-timers turn bullish when earnings seem set to jump. Usually, they pay no attention to the intrinsic value of those profit streams.

There is a market-timing signal in forecasts of corporate profit growth, but it’s not what you might think. Everyone is trying to look ahead, and your bet will pay off only if it is correct and different from what others anticipate. When it’s totally obvious that profits will be sluggish or fall, the stock market has already dropped, and it’s a great time to buy. The opposite is also true. For the four decades through 2015, in years when S&P 500 earnings growth has been fastest, P/Es have on average contracted, often so sharply that total returns were negative. When S&P 500 profits fell, on average P/Es expanded so much that stock prices increased.

To Know Yourself, Study Others’ Mistakes

In the decades since my trading debacle, I’ve seen many investors blow up their portfolios using top-down investing, basically in two related ways. They (1) invest with no notion of fair value and (2) fail to assimilate new information. Foreign currencies, commodities, and many other instruments that macro traders use don’t have an intrinsic value. Instead currencies, for instance, have a fair value implied by purchasing power parity. Without any concept of intrinsic value, it’s impossible to gauge whether the market has already picked up on your insight. To diagnose where a trade tripped up, you either need to follow all of the links between cause and effect (which is doubtful for macro trades), or you need some basis for calculating a fair value.

Investors constantly search for overlooked insights that, if widely understood, would prompt a large market price movement, but assessing what’s in the public domain can be done only obliquely. For simple situations, investors can trace the causal links and identify which element the market hasn’t grasped, which is rarely possible with complex big-picture issues. The notion of fair or intrinsic value doesn’t tell you which idea is mistaken, just that the price might be wrong. A visible gap between market price and your calculation of intrinsic value indicates that either you or the markets must be misguided.

Intrinsic value also serves as a way to determine whether an investment idea was flawed, and as a guide to action. When losing money is the only clue that something’s amiss, you are in deep trouble. Momentum investors buy stocks that have gone up and sell those that have gone down. I think this implies they would buy a rising stock at $40, sell it as it dips to $35, and then buy it again when it pops back to $41. If I believed a stock was worth $50 and purchased it for $40, I would be even more enthusiastic when the price slipped to $35, provided that the value had not changed. If the news that prompted the decline reduced my estimate of fair value to $30, I would sell and accept my loss.

In religion, politics, and love, true believers are meant to remain steadfast, regardless of the evidence. Investors aim for the rationality of natural scientists, but can never achieve it because businesses and economies are structures of human beings. As issues in economics become vast and multifaceted, they tend to shade into political and philosophical beliefs. For example, when a wealthy creditor nation cannot collect repayment from a destitute nation, people make moral and political judgments unlike those made when a business fails. When I think about social systems in ways that touch on personal values, it is hard to avoid groupthink. In cases like that, I don’t trust myself to invest strictly based on what I expect to happen rather than what I want to happen or think is right.

The garden variety versions of failures to consider intrinsic value and take in new information are permanent bears (who always expect stocks to tank) and goldbugs. This isn’t to say that bear markets don’t occur or that gold can’t be a useful store of value. Value investors are likewise intent on preserving capital, but we worry about the opportunity cost of holding assets that produce little income (like cash) or no income (like gold). Permabears and goldbugs often tell sagas of impending disaster, with accelerating inflation usually following from high and rising consumer and government debt. Every data point is reinterpreted to support their cause. It’s intelligent to worry, but that doesn’t mean the most worrisome analysis is the most intelligent.

I have some sympathy with the permabears, as the average P/E of the S&P 500 in the quarter-century between 1992 and 2016 has been higher than in the quarter-century before it, or just about any quarter-century since the index was created. Some argue that higher multiples are justified by globalization, increasing monopoly power, and new technologies. Those who believe market valuation metrics are nonetheless mean reverting have appeared to be permabears. A distinction might be found in their actions during bear markets like 2009, when market multiples tumbled far below even the averages of longer histories. If they bought stocks then, they are not permabears.

Gold may be a store of value, but how much value isn’t clear. Since gold earns no income, it has no intrinsic value, but over time it does seem to have an average value measured by a basket of consumer goods, with a huge variance. Yet in 2001, gold traded at $270 an ounce and in 2011 at $1,900. Even making a generous adjustment for consumer price inflation, in 2011 the real price of gold was five times what it had been a decade earlier. The popularity of tales of hyperinflationary disasters in Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe peaked coincidently. In a weird parallel to inflationary fears, large quantities of securitized paper gold were issued. Investors with a sense of value and the ability to change their mind might have reduced their gold holdings at that time.

Keynes: The Great Economist as Investor

When I learned that John Maynard Keynes was not only the founder of macroeconomics but also an outstanding investor, I hoped that he might provide a role model for applying economics to investing. Keynes’s approach evolved over time and brought varying degrees of success. Keynes began his career as a speculator by trading in currencies, generally buying U.S. dollars and selling short European currencies like the German mark. In 1919, Keynes wrote a book arguing that Germany would be unable to pay reparations for World War I, and that forcing it to do so would cripple its economy. That was exactly what happened, eventually.

With its economy a mess and struggling to pay reparations, Germany went into hyperinflation and the paper mark completely collapsed in 1923. Keynes would have reaped spectacular gains if he had stayed short the mark until then, but he had borrowed money to do this trade. In May 1920, the mark’s descent was interrupted by an abrupt rally, which wiped Keynes out and left him in debt to friends.

When he again had (other people’s) money to play with, Keynes returned to commodities trading. In this endeavor, he had what I would call unfair advantages: access to historical price data for commodities at a time when this information wasn’t widely available, and close connections with government policy makers. But his overall results from commodity trading were very mixed, particularly if you include some devastating losses at the start of the Great Depression.

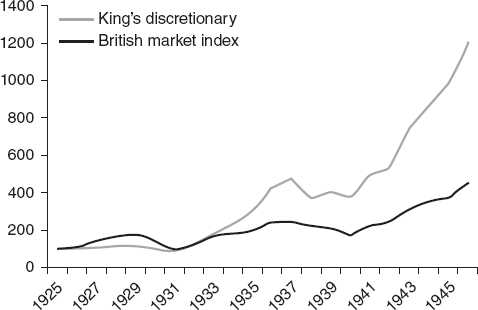

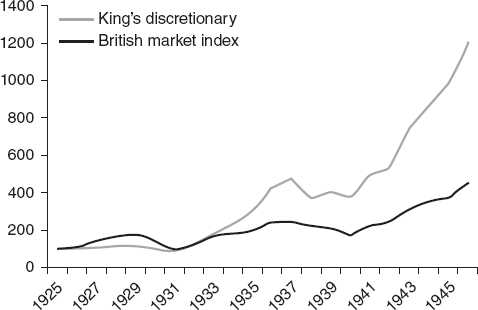

In addition to his personal account, Keynes began to manage the Chest endowment funds for King’s College at the University of Cambridge. For several years at the start, he used economic and monetary analysis to decide when to switch between stocks, bonds, and cash. In current jargon, Keynes was a top-down asset allocator and sector rotator using a momentum style. Cumulatively, his results in the 1920s lagged behind the British market (figure 7.1).

FIGURE 7.1 Keynes versus index, 1926–1946.

In his investment report to King’s College, Keynes wrote, “We have not proved able to take much advantage of a general systematic movement out of and into ordinary shares as a whole at different phases of the trade cycle.” He also observed, “Credit cycling means in practice selling market leaders on a falling market and buying them on a rising one and, allowing for expenses and loss of interest, it needs phenomenal skill to make much out of it.” If the greatest macroeconomist ever, with special access to information and policy makers, couldn’t trade successfully on credit and business cycles, I don’t know who could.

The 1929 crash and Great Depression caught Keynes by surprise, both as an economist and as an investor. In “The Great Slump of 1930,” he wrote, “We have involved ourselves in a colossal muddle, having blundered in the control of a delicate machine, the workings of which we do not understand.” Keynes personally lost about four-fifths of his net worth from top to bottom, partly because he never stopped using borrowed money. The King’s College portfolio held up better. In this portfolio, credit cycling had helped because Keynes sold shares into a falling market that kept plunging.

Keynes recognized that his approach wasn’t working and changed it. Instead of using big-picture economics, Keynes increasingly focused on a small number of companies that he knew very well. Rather than chasing momentum, he bought undervalued stocks with generous dividends. On average, the stocks he purchased had a dividend yield of 6 percent. This yield was far above that of the average British stock or bond, and, where Keynes had borrowed funds to invest, as he usually did, it more than covered the interest expense. Most were small and midsize companies in dull or out-of-favor industries, such as mining and autos in the midst of the Great Depression. Despite his rough start, Keynes beat the market averages by 6 percent a year over more than two decades.

Where Does the Efficient Market Hypothesis Apply?

Although Keynes and I both ended up favoring undervalued, mostly smaller companies, I think Keynes held a different view of our ability to predict the future. Both of us started with hopes of using economic predictions to trade markets but failed to do it well enough to make and keep serious money. Keynes wrote of the precariousness of our knowledge of the future earnings yield of any specific stock, a concern that I would extend to the future of any complex economic system.

Earlier in this book, I discussed the efficient market theory, which posits that market prices are essentially fair and that no one should expect to consistently beat the market. That would follow if all information were publicly available to everyone, and on average correctly interpreted. For statistics and trends that are universally important enough to be reported on TV or the Internet and draw audiences of millions, this seems a fair description of reality.

In its strong form, the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) states that even private or insider information will be reflected in market prices. This seems incorrect to me, as I still see news reports of large profits made with inside information on stocks. But, other than the movie Trading Places, I’m hard pressed to think of a major (real) example of insider trading on economic data. By definition, economic data involve large markets, so the potential profits should be massive. The lack of insider trading scandals hints that for economic data, the strong form of the EMH may apply. Most information about the big picture is widely known, or at least is reflected in the prices.

Thinking Small

You can’t make money in the short term from anything millions of viewers have seen on TV or the Internet. To use big-picture economics successfully, you must carefully check whether one thing really does lead to another, based on historical examples, and be alert to the possibility that you are mistaken. You have to check whether the models you learned in school work or not, and under what circumstances. The result is more of a mosaic than a data point, which does nothing to simplify things, because there are so many news reports and so many connections. Every piece of information isn’t equally important; most are redundant.

So instead, I try to think small. There are fewer news reports on a specific company than on the economy as a whole. Analysis of stocks is less a matter of careful interpretation than analysis of the economy. It’s not inside information; it’s simply that most people aren’t paying attention, especially if the company is small. Everyone makes mistakes in figuring out what the future will bring. If the connections are clearer and more direct, your forecasts are more likely to be accurate. Unlike more cosmic subjects, it is easier to know what you don’t know with a specific stock.

Any investor, big-picture or not, needs some concept of fair value to serve as his or her guide star. The idea of fair value not only indicates which trades are most attractive but also helps calibrate the weight of new information and aids in deciding whether to add to a position or reverse course. Arguably George Soros’s theory of reflexivity explains why the British pound became grossly overvalued relative to purchasing power parity, and then stopped becoming more so. Beyond that point, Soros’s most powerful tool was the notion of fair value.

Both macro investors and stock-pickers must fearlessly seek the truth, but for me smaller errors are easier to admit. Once I’ve committed to a theory that explains big, important things, I rarely change my mind. It’s more unsettling to admit that I don’t comprehend the world around me than a small situation of narrow interest. While I make fun of investors who incessantly think the stock market is about to implode or that gold is the only safe asset, I also have my own settled beliefs. An idea about a specific stock is just one among many, and I know all along that a certain fraction of them will be duds. A smaller mistake is generally easier to repair. Thinking small not only reduces the severity and frequency of errors, but it also puts you in a better frame of mind to expect them and fix them.