Part of the $10 million I spent on gambling, part on booze, and part on women. The rest I spent foolishly.

—GEORGE RAFT

Capital Allocation

THOUGH YOU MAY BE THE LEGAL OWNER of a security, many of the decisions that determine its value are made by others, so it’s essential to choose good stewards for your assets. Your agents and managers, however able, are human beings, with a tendency to favor their own interests if there is a dispute, so it’s critical to find ones with a demonstrated fiduciary mind-set. In extreme cases, normal self-interest can veer off into criminality. Often your stewards attained their position not by being capable stewards, but through ambition and other accomplishments. CEOs often got to the top by force of will and by being fantastic salesmen, plant managers, engineers, or accountants.

Lacking both the time and the inclination to send out interviewers or gumshoes to properly assess stewardship skills, I prefer to focus on capital allocation. Really, I’m more of an armchair detective. I look for something more numerical that I can get from readily available sources. Capital allocation is a clunky term, but a useful concept meaning: follow the money. Is it going to the right places? Have the managers directed the capital at their disposal to the highest and best use possible given the situation?

There are two related statistical ways to measure success—rate of return and present value—but both involve somewhat tenuous forecasts of the future. The first method compares the projected rate of return on capital improvements with a hurdle rate. Usually, this hurdle rate is tied to the “cost of equity,” or the lowest rate of return that long-term shareholders would find acceptable. If investors require a return of no less than 8 percent, the company should reject capital projects that return any less. Assuming that a company with an 8 percent cost of equity invested in something that would return 13 percent over the next year, it would have invested one dollar to create roughly $1.05 (1.13/1.08) of present value. The goal is to add the largest possible amount of value.

When I tried to study capital allocation in two of my first industry assignments at Fidelity—coal and tobacco, I was stumped. What I was missing was the idea of off-balance sheet liabilities and economic goodwill. The historical accounting numbers didn’t capture the value of capital and liabilities in these industries. For example, companies in both industries were defendants in lawsuits related to black lung disease and lung cancer. It was foreseeable that as verdicts for damages were rendered, companies would grudgingly settle claims, using capital in ways that offered no prospect of return. Cigarette companies at least had a positive offset to these anticipated liabilities in the form of powerful brand names. One subtlety was that the Surgeon General’s warning issued in 1964 acted as a partial legal shield thereafter. Cigarette companies’ exposure was proportionate to their market share in 1964. This favored Philip Morris, which had grown dramatically since then.

The other challenge was in determining the value of intangible assets such as brands. Marlboro and other powerful brands were on the books at nominal amounts but had tremendous customer loyalty, suggesting huge economic goodwill. Philip Morris and RJR Nabisco had acquired food companies with leading brands like Maxwell House and Oreo, and here the intangible acquisition cost was shown in their accounts as trademarks or goodwill. It was an accident of history that Philip Morris and RJR paid billions for their food brands and not so much for their cigarette brands. The historical cost has little to do with current value. One approach to valuing these brands is to use market prices rather than historical accounting cost. But the ratio of profits to the stock market value of a company is its earnings yield, or the inverse of the price/earnings ratio. This, while useful as an investing guide, says nothing about the quality of management’s decisions.

I decided to forge ahead and use the accounting numbers despite their defects. The ratio of a company’s earnings to its stockholder equity is called its return on equity (ROE). A high ROE suggests that a company is maximizing the profit per dollar of capital that shareholders put into the company. At the time, 12 percent was considered an average ROE. Almost the entire tobacco industry seemed to be head and shoulders better. U.S. Tobacco, which makes moist snuff, had an ROE approaching 50 percent, Philip Morris nearly 30 percent, and so on. RJR Nabisco, British American Tobacco (BAT), and American Brands all earned ROEs topping 20 percent.

In retrospect, the relative rankings of ROEs of companies in the late 1980s were a powerful indicator of their future returns. I also wanted to know the reasons for the high ROEs. U.S. Tobacco and Philip Morris had the highest returns and the most distinctive brands. U.S. Tobacco’s Copenhagen and Philip Morris’s Marlboro were (and are) by far the top brands in moist snuff and cigarettes. A more forward-looking assessment of capital allocation could be gleaned by studying specific uses of cash.

Expanding the Business or Building Value?

For potential growth projects, everything is considered on an incremental basis. The increases in sales and profits are compared with the added capital required. For tobacco companies, the profit on increased sales from an existing plant is surreal. In 2016, the cost of goods sold for Altria (parent of Philip Morris USA and U.S. Tobacco) was 30 percent of sales. Tobacco leaf, paper, filter, and packaging were less than half of the cost of goods, with legal settlements accounting for the majority. Marketing, research, administration, and corporate took another 10 percent of sales. Even after excise taxes of 25 percent of sales, an operating profit margin of 34 percent remained. (The operating profit margin for the S&P500 was about 12 percent in 2016.) If a company has spare capacity and can make and sell more products, it can spread its fixed costs. The incremental rate of profit will be even higher than the already spectacular average.

Even though returns on fixed assets are out of this world in the tobacco business, that math doesn’t apply to building new capacity. Cigarettes are made in very few factories. Producing more in one plant often means making fewer in another. If new capacity could be used as fully as the existing facilities, the profit margin on those sales might look like the overall average of 34 percent. Few businesses have margins that wide; better still, cigarettes take little capital to produce. Altria logged $25.7 billion in sales in 2014 using property, plant, and equipment with a depreciated cost of just under $2 billion. Yearly operating profits were more than 400 percent of the value of its physical plant. Obviously, that return soars above any normal hurdle rate, which might be closer to 10 percent. Distinctive businesses can grow at only a certain rate and keep their character and profitability.

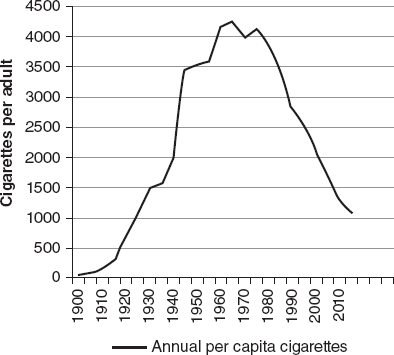

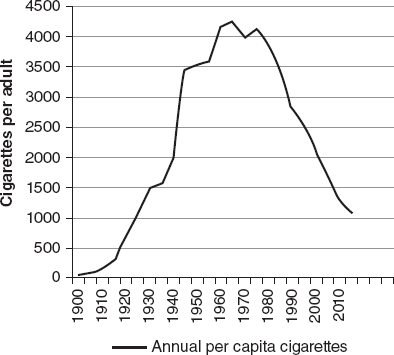

Around the world, cigarette consumption has fallen in wealthier countries (figure 10.1). By contrast, in the poorer places, rising incomes brought more smoking. In those countries, investments to expand production paid off handsomely, even though selling prices were lower. For historical antitrust reasons, the companies that owned brands in the United States often did not control them overseas—Marlboro being the prime exception. Marlboro is the truly global brand. In many cases, tobacco has been a national business. For tax and regulatory reasons, cigarettes are mostly made in the countries where they are sold.

FIGURE 10.1 U.S. cigarette consumption, 1900–2014.

In the late 1980s, as foreign markets opened up, RJR Nabisco vigorously expanded its export sales off a low base, opening a gigantic, highly efficient new plant. In many manufacturing industries, overinvestment can lead to disaster, but the Tobaccoville plant consumed only a modest chunk of RJR’s cash flow.

For cigarette companies, marketing spending was larger than capital spending, and it was critical to know whether money spent on marketing actually kept customers and brought in new ones. Advertising spending can be an investment in building brands (and economic goodwill) or just cash out the door. Managements themselves often can’t know. Unless future sales are under contract, accountants expense the whole cost. Apple, Nestlé, Louis Vuitton, and Walt Disney spend and charge off billions in marketing costs each year. Generally, their brands become more valuable over time, increasing economic goodwill. RJR was in a tough spot, supporting many smaller brands while Philip Morris had a blockbuster in Marlboro.

For Philip Morris, spending marketing dollars on a single powerhouse brand carried more potential benefits than RJR’s spending on a multitude of brands. RJR splashed out hundreds of millions on sports marketing, keeping thirty athletes on retainer. It bought billboards in stadiums so that they would be seen during televised games. Packaging was restyled. Joe Camel, a new cartoon brand mascot, drew the attention of youthful smokers and regulators. RJR maintained a stable share in a shrinking market.

In all businesses, profits and losses today stem from a collage of decisions, big and trivial, made in the sometimes distant past, often by people who are no longer around. Dumb luck can be as influential as good judgment. Ross Johnson, CEO of RJR, quipped, “Some genius invented the Oreo. We’re just living off the inheritance.”

Similarly, before it featured the rugged cowboy in its ads, Marlboro had been launched as a ladies’ cigarette that was as “mild as May.” The red filter tip, meant to hide lipstick stains, was later switched to a manly cork brown. Decades after the rebranding, Philip Morris was still reaping the benefits of an iconic package and mascot. Over a quarter of a century, the company catapulted from an also-ran to the market leader.

Price discounting suggests that either prices are too high or product features don’t matter much. Around 1984, RJR repositioned Doral as a branded discount cigarette. At sharply reduced prices, the margins on cheap smokes were lower but still attractive. By 1992, RJR’s fastest growing segments were Doral and its generic cigarettes. To gain market share, RJR dropped wholesale prices of discount cigarettes by 20 percent. It worked; the next year, 42 percent of RJR’s volume was discounted. Marlboro sales eroded, so Philip Morris slashed prices as well. My suspicion is that, having weaker brands, RJR let its marketing strategy be led by its superior manufacturing capacity.

In the 1990s, R. J. Reynolds made a controversial investment in a smokeless cigarette called Premier. Research and development for Premier cost at least $300 million, and the all-in costs may have topped $800 million. Smokers become habituated to tobacco by the nicotine, but the real health risks come from inhaling burning tar. The Premier cigarette heated tobacco and delivered nicotine vapors to smokers. Around launch time, RJR sent me a carton of Premier cigarettes. Not being a smoker myself, I turned to Beth, a portfolio manager who both smoked and invested in tobacco stocks. She pulled out her lighter and after half a dozen attempts was able to inhale a few puffs.

“Jesus!” she bellowed, “It takes a fucking blowtorch to light this thing and then it tastes like shit.”

Apparently, many others agreed. RJR advised consumers that they would need to smoke at least a couple of packs to get the hang of Premier, but Beth didn’t stick around for that. About a year later, RJR folded Premier, although the vapor idea was later revived as Eclipse. At the time, I thought that the whole fiasco was a colossal boondoggle. With hindsight, perhaps RJR should have pushed Premier harder. Jump ahead to the new millennium when better e-cigarettes and vaping technology have entered the market. RJR launched Vuse e-cigarettes, which finally did get a favorable reception.

RJR generated far more cash than it invested. Unless a business is growing exponentially, I expect it to be financially self-sufficient with internally generated funds (including retained profits) more than enough to cover all of its growth. To check this, I look to the statement of cash flows in a company’s financial report. Cash flows from operations are the sum of net income, depreciation, amortization, changes in working capital, and other items. Then I sum up all the categories of capital spending needed to maintain and expand the business. These include purchases of property, plant, and equipment and investment in software, but not purchases of investments or other businesses.

My definition of “free cash flow” is “cash flows from operating activities” minus all of the cash paid out for the investing activities listed above. Then and now, tobacco firms reinvested tiny fractions of their cash flows in the business. In 2014, Altria had $4.663 billion of cash from operations. Capital spending was $163 million, a bit under depreciation. This left $4.5 billion of free cash flow. Free cash flow is available to buy businesses and investments, pay off debt, or return to shareholders through dividends or share buybacks. We’ll soon come back to those alternatives.

Most companies that run negative free cash flow are trying to grow faster than their ROE will allow. If a corporation doesn’t issue or buy back stock or pay dividends, its equity will grow at the same rate as its ROE. Despite recent ROEs of more than 100 percent, Altria is not trying to grow 100 percent a year. There are congenital optimists who habitually outspend cash flow in industries such as independent oil and gas, home building, and airlines.

To tell whether negative free cash flow is worrisome or not, I check a company’s ratio of profits to capital invested—that is, its return on capital employed (ROCE). This is defined as operating profits as a percent of total capital, including both debt and equity. I’m much more impressed by an ROE of 13 percent based on a 13 percent ROCE with no debt than by the same ROE built on a 7 percent ROCE and a lot of debt. In a downturn, the profits of the levered company usually fall harder. A low or falling ROCE might signal that management is taking on some mediocre projects. When low or falling returns persist for years, I’m especially wary of negative free cash flow and rising debt.

Acquisitions and Spin-Offs: Bigger or Better?

Most studies say something like two-thirds of acquisitions miss the financial targets used to justify their purchase price. Acquisitions rarely happen without the buyer paying a control premium. To earn back the premium, a buyer must do something with a company that wasn’t already being done. Profits have to be improved somehow. That could happen by increasing sales or cutting costs or at least avoiding taxes.

Some deals are about financial engineering and rely on borrowing money cheaply or the willingness of the buyer to accept a lower rate of return. Often the shares of the acquiring company slip after the deal is announced. In general, the mergers and acquisitions that have the best odds involve low valuation multiples and premiums and combine similar businesses.

The specter of antitrust litigation prevented takeovers in the tobacco industry until the mid-1990s; then there was a deluge. In 1994, American Brands sold its American Tobacco Company to BAT’s Brown & Williamson division and changed its name to Fortune Brands. In 2003, BAT’s Brown & Williamson was merged into Reynolds American, giving BAT a 42 percent stake in the combined company. RJR sold its international operations to Japan Tobacco and bought Conwood, a moist snuff producer. U.S. Tobacco was purchased by Altria in 2009. In 2014, Reynolds agreed to acquire Lorillard. As far as I know, none of these deals has disappointed. They were done at reasonable prices and were of businesses the managers understood well enough to know where to find cost savings.

RJR Nabisco returned to the public market in 1991, two years after its mostly debt-financed buyout by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR). RJR set about selling bits and pieces of businesses and carved out Nabisco as a separate food company. In 1995, 19 percent of Nabisco was sold in a public offering. Before the buyout, RJR’s powerful brands gave it a large amount of economic goodwill, but after the buyout, their value was fully (maybe overly) reflected on its balance sheet as intangible assets of more than $20 billion. Both RJR Nabisco and Nabisco limped through the 1990s with single-digit ROEs in most years.

Acquirers must do something different with a business to justify paying a takeover premium, so it’s not surprising that results were generally best in somewhat-related businesses. Packaged food and cigarettes are mass-market perishable consumer goods made with agricultural inputs. RJR’s tobacco executives probably understood Nabisco’s marketing and distribution strategies far better than they understood anything about shipping or oil. Likewise, Philip Morris was happier with General Foods and Kraft than with Mission Viejo, the home builder.

When a buyout is announced, historical operating profits and the price are usually disclosed as well, so an analyst can estimate a ROCE. It will, of course, be a low estimate as it doesn’t reflect the profit improvements yet to come. The RJR Nabisco leveraged buyout had a $31 billion enterprise value—cash price plus debt assumed—and $2.8 billion in operating profit, for a ROCE of 9 percent. Even if nothing changed, it looked like an OK—but not amazing—deal.

Tobacco companies have reversed almost all of their diversification, indicating that either times have changed or it was a mistake all along. In 2000, RJR sold Nabisco to Philip Morris, leaving only tobacco operations. (Later it renamed itself Reynolds American.) In 2007, Philip Morris spun off Kraft, including Nabisco. The next year, Philip Morris split into Altria and Philip Morris International. During the period when Reynolds was a pure play and Philip Morris was diversified with Kraft Foods, Reynolds’ stock more than quadrupled, while Philip Morris’s stock more than tripled. Both were far in front of the stock market, but the pure tobacco company did better. RJR had resumed buying back stock and outdid Philip Morris, but this was partly a side effect of the Nabisco transaction, because Philip Morris had less cash to buy back its shares, having paid $9.8 billion to RJR to acquire Nabisco.

Philip Morris spun off Kraft in 2007 (and later Kraft spun out Mondelez). The stocks of the food company spin-offs have beaten the market, but so have the cigarette stocks. If there were benefits to the combinations, no one seems to have missed them. And these were the biggest, best deals. I don’t think anyone really expected great things from the plant nursery, ballpoint pens, mortgage banker, or shipping line. For most executives, it’s an unnatural act to reduce their prestige and span of control by spinning off and selling businesses. When it becomes clear to them that it is the best course of action, shareholders have often been asking for it for years.

Businesses create wealth by making profits. Usually dividends reflect those profits, but paying a dividend doesn’t itself create wealth—it just distributes the wealth that was created. In the twentieth century, most companies paid out half or more of their earnings in dividends. Currently, most companies issue dividends of less than half their profits. There are several reasons for this, including tax policy, the institutionalization of investing, and the rising popularity of stock options. Dividends are taxed as received, whereas the tax on the capital gain resulting from share buybacks is deferred until the investor sells. Most employee stock option plans do not adjust for dividends, so executives act as if the goal is the highest possible stock price rather than the greatest total return.

Companies that pay out a large proportion of their profits as dividends transmit two sometimes contradictory signals. First, a high payout ratio hints that a company has demanding standards for returns on expansion projects. Since the company can’t find highly profitable growth projects, it is returning the cash to shareholders, who can use it better. A company with an unremarkable return on equity that isn’t returning cash to shareholders may be putting money into projects with mediocre returns. It’s especially worrisome if assets are growing robustly but profits are not.

Second, the payout ratio tells you whether the company sees a lot of profitable expansion opportunities. Small companies that are trying to grow explosively usually don’t pay dividends. Some companies are more optimistic and confident about their prospects than others. Berkshire Hathaway has not paid a dividend since Warren Buffett arrived; share repurchases have been rare as well. This profile proclaims supreme confidence in Berkshire’s ability to allocate capital better than its investors. For most CEOs other than Buffett, I would infer hubris or low standards for returns. Tobacco companies have the opposite approach. They pay out roughly three-quarters of profits as dividends and top that off with share repurchases.

Statisticians say that stocks with healthy dividends slightly outperform the market averages, especially on a risk-adjusted basis. On average, high-yielding stocks have lower price/earnings ratios and skew toward relatively stable industries. Stripping out these factors, generous dividends alone don’t seem to help performance. So, if you need or like income, I’d say go for it. Invest in a company that pays high dividends. Just be sure that you are favoring stocks with low P/Es in stable industries. For good measure, look for earnings in excess of dividends, ample free cash flow, and stable proportions of debt and equity. Also look for companies in which the number of shares outstanding isn’t rising rapidly.

To put a finer point on income stocks to skip, reverse those criteria. I wouldn’t buy a stock for its dividend if the payout wasn’t well covered by earnings and free cash flow. Real estate investment trusts, master limited partnerships, and royalty trusts often trade on their yield rather than their asset value. In some of those cases, analysts disagree about the economic meaning of depreciation and depletion—in particular, whether those items are akin to earnings or not. Without looking at the specific situation, I couldn’t judge whether the per share asset base was shrinking over time or whether generally accepted accounting principles accounting was too conservative. If I see a high-yielder with swiftly rising share counts and debt levels, I assume the worst.

Share Buybacks

The winners and losers from buying back shares depend on the price the company pays for them. Like dividends, share buybacks distribute wealth; they don’t create it. Unlike dividends, however, share buybacks can redistribute wealth among shareholders. If shares are repurchased at intrinsic value, the transaction is fair to all. But when shares are repurchased at a premium over intrinsic value, value is taken away from loyal shareholders and given to those who depart. When shares are repurchased at a discount from intrinsic value, selling shareholders lose and the remaining shareholders gain. Different people will arrive at different estimates of intrinsic value, so it’s not always clear whether a buyback occurred at a favorable price or not. Without an estimate, though, one can’t judge whether management is adding to per share value by buying back stock.

To understand the transfer of wealth, consider a corporation with 100 shares, whose only asset consists of $10,000 in cash with no ongoing business. The intrinsic value of each share is equal to the proportional share of the cash, or $100. Suppose that forty shares were repurchased for $160 a share, for a total of $6,400. The company would then have $3,600 in cash and sixty shares outstanding, or $60 per share. Selling shareholders would be ahead by $60 a share, while loyal shareholders would lose $40 per share in intrinsic value. Conversely, when a company buys back shares at a discount to intrinsic value, the loyal shareholders gain a proportionate share of that discount.

Buybacks are most popular when companies are feeling flush, and those are often the moments when buybacks are least beneficial. As the market was topping out in the third quarter of 2007, S&P 500 companies bought back $171 billion of stock. A year and a half later, the S&P crashed to half its former value, and in the first quarter of 2009, only $31 billion of stock was repurchased. This is disappointing not just because the timing of the buybacks was inopportune, but also because buybacks signal confidence in the company’s value and outlook. Cheer is most appreciated when despair is all around. When I study some buybacks that turned out badly, I find that very few companies took the action because of a discount to intrinsic value.

Technology companies especially try to offset the dilution from hefty employee stock option grants. As share prices rise and options become more in the money, accountants consider a rising fraction of the shares under option to be outstanding. To keep a constant share count, shares will be bought back most urgently at the peak. Many companies have issued shares under option at lower prices and later repurchased them at higher prices. Return to our previous example of a company with 100 shares and $10,000 in cash. Suppose that it issued options on fifty shares to employees with a strike price of $100. Based on an option pricing formula, the value of the options might be calculated as $10 each or $500 in total. This amount would be reflected in the profit and loss, although shareholders would be urged to ignore it as a noncash charge. Suppose the stock then leaped to $160, all of the options were exercised, and the fifty new shares were repurchased. The company would collect $5,000 from the options exercise and shell out $8,000 to buy them back, leaving its cash balance at $7,000. Although the share count is steady, shareholders are out $3,000, or $30 per share.

Another reason why buybacks peak along with the stock market might be that a company’s profits are topping out then. Perhaps cash should be returned to shareholders. But there’s no law that requires this to be done immediately. In prosperous times, estimates of intrinsic value will be higher. Perceptions of the best balance of debt and equity will be less conservative. This may encourage companies to make an ill-timed decision to move to a more “efficient” balance sheet. That means taking on debt to buy back stock. If it is late in the economic cycle, and profit growth is slowing, per share earnings growth can be sustained by borrowing money to repurchase stock.

All of the tobacco companies consistently repurchase stock and have usually added value in doing so. The exception was RJR during the 1990s. Restrained by a large debt burden, it not only didn’t buy back stock, but it also had to issue equity. I was glad that by this time I was no longer the tobacco analyst. RJR stock had fallen from its initial launch price, went sideways for years, popped, and slumped, leaving it lower at the end of the decade. Between 1990 and its peak in 1998, Philip Morris shares quadrupled in price, putting it miles ahead of the index and RJR, with the help of large stock buybacks. As RJR’s finances strengthened, and after it sold Nabisco, it stepped up share repurchases and, as noted earlier, outperformed Philip Morris in the new millennium.

Stable, High Returns

Philip Morris and Reynolds were both above average in creating distinctive businesses and in allocating capital, but between them, Philip Morris was superior. In the 1970s, the total return on R. J. Reynolds was better than the overall market, but Philip Morris was far ahead. The same was true in the 1980s, if you take out the run-up to RJR’s buyout in 1988. KKR’s investors did not make money on the RJR deal, so again Philip Morris was in the lead. The pattern continued through the 1990s, but reversed in the new millennium.

One indicator of superior capital allocation is high and stable ROCE. Philip Morris’s returns were higher and more stable over several decades. In some industries, an outsider can use rules of thumb to estimate incremental returns on growth projects and advertising, but not in tobacco. My sense is that Philip Morris did a more effective job. Mergers and acquisitions can be very good or very bad but, on average, disappoint. The odds are best for combinations of related businesses done at reasonable prices. Philip Morris had more success with its acquisitions than Reynolds, which may be why it continued to diversify even as Reynolds was going back to basics. Spin-offs go against the normal empire-building tendency, and as a result are often fantastic opportunities for investors.

If a company lacks opportunities to use capital at higher returns than an investor can find in the stock market, it should return the capital to shareholders through share buybacks or dividends. Through the 1990s, Reynolds’s stingy capital return policy was a major factor in its underperformance. Because of declining volumes, litigation, and taxation, P/E multiples on tobacco stocks have generally been lower than for the S&P 500. All of those factors would have to go into the valuation of tobacco stocks, but I would submit that most of their share repurchases have been at least neutral to the remaining shareholders, and often quite positive.