TABLE 1.3

Royal Self-Interest and Religious Choices, Autocratic Regimes Only

|

Level of Economic and Political Benefits of Becoming Protestant |

Choosing Catholicism |

|

|

Low |

France |

|

Spain |

Low |

Portugal |

Low |

Spanish Netherlands |

Low |

Poland |

Low |

Italy |

Low |

Choosing Protestantism |

|

|

High |

England |

|

Northwestern German States |

High |

Denmark |

High |

Sweden |

High |

There are two very different issues here. I am quite willing to substitute “Catholic Reformation” for “Counter-Reformation.” But it is bad history to assert that the changes begun at the Council of Trent326 (1562–1563) were not provoked by the rapidly rising tide of Protestantism. To hold such a view is to ignore that while the council was in session, France was fighting a bitter civil war to determine whether Catholics or Huguenots would prevail. Indeed, to suppose that the great reforms begun at Trent were due to happen regardless of Protestant agitation is to ignore the fact that the Church of Piety had been trying to achieve a reformation for many centuries, and even reform-minded popes had failed to make any headway.

There is nothing discreditable about admitting that the Catholic Reformation, which had been gestating for so long, required a vigorous Protestant push to be born. What is important is that the Church of Piety did assert its power at Trent. Subsequently, with the aid of such new religious orders as the Jesuits and reinvigorated orders such as the Carmelites, the Church of Piety soon dominated the Roman Catholic Church, and, at long last, the reformers achieved their goals. Simony was ended. Popes and bishops became models of piety. Official, inexpensive, Catholic vulgates were made readily available in all major languages. The Church did undertake to evangelize and educate the rank and file, and continues to do so.

All of these reforms were greatly influenced by what has been called the most significant decision taken at Trent: to establish a network of seminaries to train men for the local priesthood. Previously, the only training most parish priests received was to serve as an apprentice to another priest who had also been an apprentice. Consequently, during the previous centuries many priests had been illiterate or nearly so. Many could not actually say a mass but simply mumbled nonsense syllables. And few knew even elementary points of doctrine—many were unable even to repeat the Ten Commandments or list the Seven Deadly Sins.327 The decision to establish seminaries (for which bishops were given special authority to divert funds from other activities) soon began to remedy these priestly deficiencies. By the eighteenth century, in most places the Church was staffed by literate men well versed in theology. Perhaps even more important, the seminaries produced priests whose vocations had been shaped and tested in a formal, institutional setting.328

This was the positive side of the Catholic Reformation. Unfortunately, perhaps inevitably, the laxity of the Church of Power had benefits that disappeared along with its many shortcomings. Hence many intellectual and economic pursuits that flourished before Trent were soon discouraged or even prohibited for several centuries. This has led to many misperceptions. For example, following Max Weber the view has been widely held that Protestantism gave birth to capitalism and hence to the Industrial Revolution, these being somehow incompatible with Catholic perspectives and policies. In fact, capitalism and industrialization did not suddenly erupt subsequent to the Protestant Reformation. Rather, as Hugh Trevor-Roper explained, they developed gradually, and medieval capitalist enterprises “were as ‘rational’ in their methods, as ‘bureaucratic’ in their structure, as any modern capitalism … The idea that large-scale industrial capitalism was ideologically impossible before the Reformation is exploded by the simple fact that it existed.”329 However, the repressive activities and policies imposed by the Counter-Reformation resulted in the massive migration of capitalists and of whole industries from Catholic areas, such as Italy and the Spanish Netherlands, into Protestant domains, with the result that Protestant nations soon forged far ahead. As Fernand Braudel put it, “[the Protestant Ethic thesis] is clearly false. The northern countries took over the place that earlier had so long and so brilliantly been occupied by the old capitalist centers of the Mediterranean. They invented nothing, either in technology or in business management.”330

The same sort of thing happened in science. As will be clear in the next chapter, the rise of Western science was rooted in Scholasticism, and Catholics played as prominent a role as did Protestants in the “Scientific Revolution” of the sixteenth century. But as the Catholic Reformation developed, increasingly severe restrictions were imposed on science, especially in the universities under Church control, and Catholic contributions to science rapidly declined, encouraging incorrect notions about the Protestant roots of science. Of these matters, more later.

CONCLUSION

The history of reformations and sects did not end in the seventeenth century. I could have greatly extended this chapter by examining how various Protestant and Jewish bodies drifted into laxity over the past several centuries, causing them to externalize a host of sect movements. Indeed, many contemporary Western religious groups,331 including the Methodists, Episcopalians, Reform Jews, and even Unitarians, are at present undergoing serious reformations, as are many Islamic and Hindu bodies around the world. But I have written enough elsewhere on these more recent developments. In this chapter my aim was to reveal the rather simple underlying mechanisms that generate the desire for reformations and prompt the eruption of sect movements. Although social scientists have been wrong to assert that material motives lie hidden behind all sects and reformations, they have been right to regard these as generic phenomena. Sects and reformations are also inevitable phenomena because, even if there is only One True God, there can never be only One True Church.

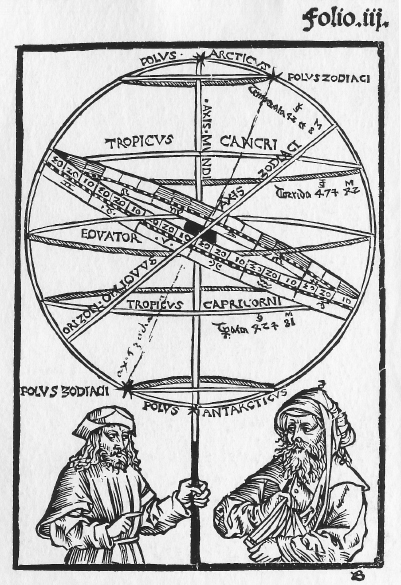

Medieval Globe. This engraving of scholars with a globe, on which the equator, the tropics, the poles, and magnetic north and south are well marked, appeared in a textbook on Ptolemy’s cosmology published at the University of Cracow at about the same time that Columbus set out on his first voyage. © Bettmann/CORBIS.