Chapter 1

Climate Action Planning

To prevent the worst impacts of climate change, we have to cut greenhouse gas emissions even as the population grows. Cities are showing that it can be done—and that the same steps they’re taking to reduce their carbon footprint are also strengthening their local economies, creating jobs, and improving public health.1

—Michael R. Bloomberg, former mayor of New York City, UN secretary-general’s special envoy for climate action, and president of the C40 Board

The Fourth National Climate Assessment prepared by the U.S. Global Change Research Program in 2018 clearly establishes the nature of the global warming problem:

The impacts of climate change are already being felt in communities across the country. More frequent and intense extreme weather and climate-related events, as well as changes in average climate conditions, are expected to continue to damage infrastructure, ecosystems, and social systems that provide essential benefits to communities. Future climate change is expected to further disrupt many areas of life, exacerbating existing challenges to prosperity posed by aging and deteriorating infrastructure, stressed ecosystems, and economic inequality. Impacts within and across regions will not be distributed equally. People who are already vulnerable, including lower-income and other marginalized communities, have lower capacity to prepare for and cope with extreme weather and climate-related events and are expected to experience greater impacts. Prioritizing adaptation actions for the most vulnerable populations would contribute to a more equitable future within and across communities. Global action to significantly cut greenhouse gas emissions can substantially reduce climate-related risks and increase opportunities for these populations in the longer term.2

Global warming is already impacting human health and safety, the economy, and ecosystems. As greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions continue to accumulate in the atmosphere, global warming impacts will increase in severity. The global challenge is twofold: reduce the human-caused emissions of heat-trapping gases and respond to the negative climate impacts already being felt and the likelihood that they will worsen in the future.

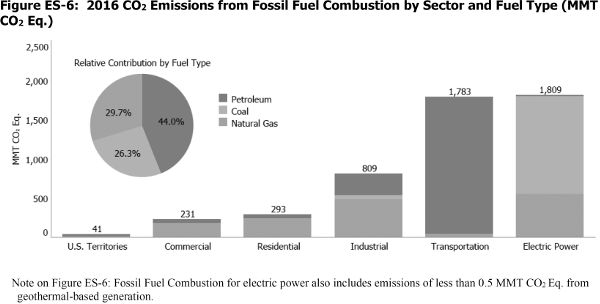

The largest sources of these heat-trapping GHGs are fossil fuel–burning power plants and fossil fuel–burning vehicles (see figure 1.1). For the former, changes such as better technology, the development of large-scale renewable energy, and the retirement of old, inefficient power plants (especially those that burn coal) have an important role to play in reducing GHG emissions. For the latter, evolving vehicle and fuel technology and standards help reduce GHG emissions. These types of technological evolution and large-scale energy programs are driven by private-sector investment and federal and state government legislation and programs. Although these efforts are important and necessary, the problem of global warming cannot be solved without the participation of communities, local governments, and individuals as well.

Figure 1-1 2016 CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion by sector and fuel type

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2016” (2018), https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks-1990-2016.

Local action is critical for the necessary GHG emissions reductions to occur. Local governments control the vast majority of building construction, transportation investments, and land use decisions in the United States. Civic and business organizations, environmental groups, and citizens can join forces with local governments and commit to local action that includes energy-efficient operation of local government; energy-efficient buildings; renewable energy systems; alternatives to driving, such as buses and bicycles; and city planning that improves the quality of life and allows people to depend less on their cars. The goal is to create low-carbon, resilient communities.

Fortunately, communities all over the world are responding to the challenge of climate change by assessing their GHG emissions and specifying actions to reduce these emissions. As of early 2019, over 9,000 mayors representing over 780 million people around the globe had made a commitment to address climate change through the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy (see box 1.1). These mayors have made commitments to reduce GHG emissions by 1.4 billion metric tons by 2030. At the 2018 Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, numerous mayors reported on their progress and made new commitments to accelerate their ambition in addressing climate change. The Lord Mayor Clover Moore of Sydney declared,

Greenhouse [gas] emissions in the City of Sydney peaked in 2007 and have declined every year since—despite our economy expanding by 37 percent. We’ve achieved this because we developed a long-term plan with ambitious targets and we determinedly stuck to that plan for over a decade. We have one of the largest rooftop solar programs in Australia, we converted our streetlights to LED and we’re working with industry leaders to reduce their emissions. We lead by example and we partner with businesses and residents to help them on their journey. As the first government in Australia to be certified carbon neutral, our achievements show the impact that can be had at a City level despite shocking inaction from State and National Governments.3

San Francisco mayor London Breed stated,

Our greenhouse gas emissions peaked in 2000, [and] since then, we’ve successfully reduced them by 30% from 1990 levels, while growing our economy by 111% and increasing our population by 20%. But in order to fully realize the ambitions of the Paris Climate Accord, we must continue to make bold commitments and accelerate actions that reduce emissions and move us towards a clean energy future. That is why, in addition to formally joining the Sierra Club’s nationwide clean energy campaign, San Francisco is committing to reducing landfill disposal by 50% by 2030 and ensuring all of our buildings are net-zero emissions by 2050.4

As of 2019, over 200 U.S. cities and counties had committed to over 500 climate actions through the United Nation’s Global Climate Action portal (see figure 1.2). In the last decade, the field of climate action planning has rapidly advanced from the commitment and planning phase to the implementation phase. Many communities are now showing success in both reducing GHG emissions and becoming more resilient.

Figure 1-2 U.S. cities and counties committed to climate action as reported on the Global Climate Action platform (as of January 2019)

Source: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, http://climateaction.unfccc.int/.

Local action is also occurring on climate adaption. One of the most notable global initiatives was 100 Resilient Cities (100RC), started by the Rockefeller Foundation. The 100RC program sought to embed the urgency of climate adaption within the broader social, cultural, and economic issues of the city. Becoming a resilient city isn’t just responding to climate change; it is also addressing such issues as food security, access to jobs, and social justice to create a resilient community in the most comprehensive sense. The program provided participant cities with support for hiring a chief resilience officer (CRO), developing a resilience strategy, and accessing a global network of partners and fellow cities. Most of the participant cities have now completed resilience strategies and hired a CRO. In Norfolk, Virginia, the CRO is directing an effort “to transform an area of highly concentrated poverty adjacent to downtown into a vibrant mixed-income and mixed-use neighborhood.”5

Also at the local level, many U.S. colleges and universities are leading the way in climate action planning. As of early 2019, nearly 500 U.S. colleges and universities had committed to climate action through the Second Nature Climate Leadership Network. Many of these colleges and universities have pledged to assist their local communities in pursuing their own climate action goals. There is a great opportunity for communities to partner with their local colleges and universities to share knowledge and resources and engage in collaborative planning.

The tremendous variety of efforts taking place in cities, counties, and colleges and universities to address the problem of climate change is impressive and suggestive of the need to establish “best practices” in this field of planning for GHG emissions reduction and climate change adaptation. This book provides basic guidance on conducting local climate action planning, including the preparation of climate action plans and other policies and programs. The information in the book should be useful to cities, counties, colleges and universities, tribal governments, and other local government entities, since the basic climate action planning process is the same. Although climate action is needed at higher levels of government as well—states, nations, and international organizations—this book focuses on the local level but addresses the linkages across the various scales of action.

What Is Climate Action Planning?

Climate action planning is a strategic planning process for developing policies and programs for reducing (or mitigating) a community’s GHG emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change. Climate action planning may be visionary, setting broad outlines for future policy development and coordination, or it may focus on implementation with detailed policy and program information. Although there is no official process for climate action planning, the most commonly followed has been ICLEI’s Cities for Climate Protection Five Milestones.6 A review of existing guidance and best practice shows that climate action planning is usually based on GHG emissions inventories and forecasts, which identify the sources of emissions from the community and quantify the amounts. Communities usually also identify a GHG emissions reduction goal or target. To reduce emissions and meet the reduction target, climate action planning typically focuses on land use, transportation, energy use, and waste, since these are the sectors that produce the greatest amount of GHG emissions, and may differentiate between community-wide actions (including the public’s) and local government agency actions. This book refers to these actions as emissions reductions or reduction strategies rather than using the terms mitigation or mitigation strategies. Additionally, many communities now address how they will respond to the impacts of climate change on the community, such as sea-level rise, extreme heat and wildfire, and changes in ecological processes; this is usually referred to as climate adaptation (see box 1.2).

The outcomes of a climate action planning process can be documented, codified, and implemented in a number of ways. Many communities have chosen to adopt stand-alone climate action plans (CAPs). Others choose to integrate the developed climate action strategies into comprehensive land use plans, “green” plans, sustainability plans, or other community-level planning documents (see box 1.3). For example, New York City prepared a sustainability plan titled PlaNYC that addresses housing, open space, brownfields, and water and air quality as well as climate change. The City of Hermosa Beach, California, integrated climate policy and programs throughout their community general plan. Yet others are acting more incrementally as opportunities arise to integrate climate action, such as during the update of a zoning code or when evaluating investments in coastal infrastructure.

Climate action planning can vary in role and scope based on community context and local vision. Role refers to the purpose that the planning serves in the community. Scope refers to the topics or issues that the planning process covers. Communities need to consider the following points as they make decisions about the roles and scopes of their own climate action planning. In turn, these decisions should direct the climate action planning process.

Climate action planning performs these functions in a local community:

- 1. Establishes actions necessary to reduce local GHG emissions and meet desired targets

- 2. Establishes actions for adapting to climate change–induced impacts and hazards

- 3. Establishes accountability for action

- 4. Brings stakeholders together

- 5. Informs the public

- 6. Integrates actions from various community plans

- 7. Integrates actions across different scales (local, regional, state, federal, international)

- 8. Saves money through energy efficiency and builds the local economy

- 9. Improves community health and livability

- 10. Responds to local context and conditions7

The following are standard contents of a stand-alone climate action plan and are instructive of what to address in any climate action planning initiative (also see box 1.4):

- 1. Background on climate change and potential impacts, including a climate vulnerability assessment

- 2. An inventory and forecast of local GHG emissions

- 3. Goals and objectives, including GHG emissions reduction targets

- 4. Emissions reduction strategies (quantified, based on the best available science, and appropriate for the jurisdiction) that cover energy, transportation, solid waste, and land use

- 5. Adaptation strategies (based on the best available science and appropriate for the jurisdiction)

- 6. An implementation program, including assignment of responsibilities, timelines, costs, and financing mechanisms

- 7. Monitoring and evaluation programs

Climate action planning has two technical or quantitative tasks that can be challenging to complete: GHG emissions accounting and climate vulnerability assessment. GHG emissions accounting includes GHG inventorying, forecasting, and reduction strategy quantification. GHG inventories include identification and quantification of GHGs emitted to the atmosphere from sources within the community over a period of time, usually a calendar year. These emissions are not measured directly; instead, they are estimated based on quantifying community activities and behaviors such as the number of miles driven in vehicles and the amount of electricity consumed by residences and businesses. For example, the City of Hoboken, New Jersey, conducted a GHG emissions inventory using the ICLEI ClearPath tool and determined that the community emitted 415,423 metric tons of GHGs in 2017 (7.5 tons per capita). The emissions sources were split among the residential sector (21%), the transportation sector (33%), the industrial and commercial sector (36%), and the waste sector (10%).8 The GHG emissions inventory also usually contains projections of future emissions that provide a basis for reduction targets and a benchmark for progress toward achieving them.

There are various approaches for inventorying GHG emissions, but a global protocol has been developed that is now in common use and is considered best practice. Moreover, communities participating in global agreements or reporting protocols may be required to use this protocol. When applied in the U.S., it is actually three related and consistent protocols depending on the use (see chapter 4 for more detail). They are

- 1. the Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventories,9

- 2. U.S. Community Protocol for Accounting and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions,10 and

- 3. Local Government Operations Protocol (LGO Protocol).11

The complement to the GHG emissions inventory is the development of GHG emissions reduction strategies. Reduction strategies are tied quantitatively to the emissions detailed in the inventory to demonstrate that they help reach emissions reduction targets. Predicting emissions reductions from reduction strategies requires that numerous assumptions be made about future local behavior and the feasibility of implementation for each strategy. For example, the City of Cincinnati, Ohio, identified a reduction strategy in collaborating with “regional bicycling advocates in order to increase bicycle use as a mode of transportation.”12 They then estimated that it would reduce annual GHG emissions by 6,300 tons per year by gathering data on existing and forecasted transportation mode share, average bicycle trip length, and vehicle emissions factors. A key assumption was that this collaboration could achieve a fourfold increase in the percentage of workers over the age of 16 that bike to work. Through future monitoring and evaluation, the City can determine the accuracy of its predictions and make necessary adjustments.

The second technical area of climate action planning is climate vulnerability assessment. This involves first identifying the climate change and associated hazards that a community will be exposed to—for example, sea-level rise, extreme heat, or flooding—and then identifying community infrastructure, assets, and functions that are susceptible to being impacted by these hazards. In addition, communities are now examining how climate impacts will affect various segments of their populations; this is referred to as social vulnerability assessment.

There are no formal protocols for assessing climate vulnerability, nor has a clear set of best practices emerged. Nevertheless, several states have prepared guidance and tools, most notably New York and California. The State of New York developed the New York Climate Change Science Clearinghouse to support state and local decision-making.13 The Clearinghouse includes maps, data, and supporting tools and documents to conduct a vulnerability assessment and prepare plans and policies. The State of California developed the Adaptation Clearinghouse, ResilientCA,14 to provide climate adaptation and resiliency resources, including the Adaptation Planning Guide and Cal-Adapt, among others. The Adaptation Planning Guide assists local governments in assessing climate vulnerability and developing adaptation plans and policies.15

Once GHG emissions inventories and climate change vulnerability assessments are complete, the challenge for the community will be clearer. The community can then begin developing strategies for becoming low-carbon and resilient. GHG emissions reduction strategies usually are in the areas of land use, transportation, renewable energy and clean fuels, energy conservation and efficiency, industrial and/or agricultural operations, solid waste management, water and wastewater treatment and conveyance, green infrastructure, and public education and outreach. Although these categories are fairly consistent across communities, the reduction strategies within the categories vary. Climate adaptation strategies also share common categories such as buildings and infrastructure, human health and safety, economy, and ecosystems with variation among local measures. For climate action strategies to be implementable, they must reflect the local context, including emissions sources and relative amounts, geographic location, climate and weather, natural hazards, existing policy, employment base, transportation modes, development patterns, community history, and local values and traditions. These factors inform decision-making as to which emissions reduction or adaptation strategies are most likely to be locally effective.16

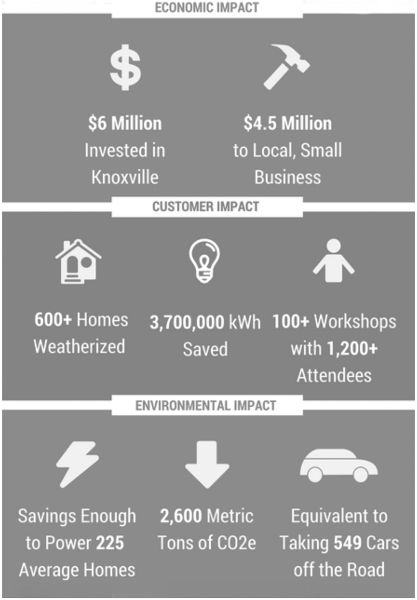

Climate action planning often addresses the co-benefits of the emissions reduction and climate adaptation strategies. Co-benefits accrue in addition to the primary climate benefits (see figure 1.3). For example, residential energy efficiency programs often decrease homeowners’ power bills, bicycling incentives promote health and recreation, and tree planting improves air quality and community aesthetics. Communities may emphasize co-benefits more than climate benefits to garner broader support for climate action planning. For example, in Knoxville, Tennessee, the award-winning Knoxville Extreme Energy Makeover (KEEM) program is an energy efficiency program aimed at assisting and educating low-income families. The program has reduced energy use, thus lowering residents’ bills, and has provided numerous other co-benefits (see figure 1.4): “By investing in homes, creating jobs, supporting local businesses, teaching life-long habits, and improving energy efficiency, KEEM creates lasting and meaningful economic, environmental, and social impacts.”17

Figure 1-3 Categories of co-benefits identified in the City of San Luis Obispo, California, climate action plan

Source: City of San Luis Obispo, Climate Action Plan (2012), https://www.slocity.org/government/department-directory/community-development/sustainability.

Figure 1-4 Benefits of the Knoxville Extreme Energy Makeover (KEEM) program

Source: “Knoxville Extreme Energy Makeover,” City of Knoxville, http://www.knoxvilletn.gov/government/city_departments_offices/sustainability/keem.

Because climate action planning has novel technical requirements, it is becoming a specialized area of professional practice. In addition to nonprofit organizations that specialize in providing planning guidance and technical assistance—such as ICLEI–Local Governments for Sustainability, C40 Cities, and the Urban Sustainability Directors Network—a number of consulting firms specialize in GHG emissions inventories, climate change vulnerability assessments, and climate action planning services. Many communities are creating high-level staff positions to oversee preparation and implementation of climate action and sustainability plans, policies, and programs. Professional associations are offering training and support for members specializing in climate change issues. Colleges and universities are offering classes and certificate programs, and full-degree programs are emerging. This book contributes to this emerging field by guiding climate action planners and others interested in the field through the planning process by identifying the key considerations and choices that must be made in order to ensure locally relevant, implementable, and effective climate action strategies.

Why Is Climate Action Planning Needed?

Climate change is a global phenomenon that cannot be adequately addressed at any one scale. Both reducing GHG emissions and adapting to unavoidable climate impacts require action at the local level as well as the state, federal, and international levels. This section summarizes the science and predicted impacts of climate change globally and in regions of the United States (appendix A provides a discussion of the science of climate change). Following these descriptions are discussions of the need for solutions at the global and local scales.

The Global Problem

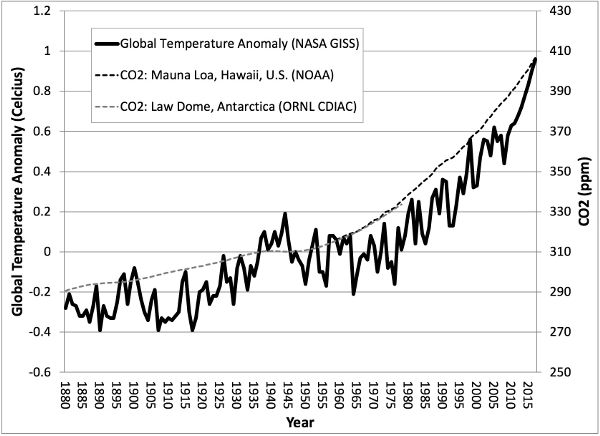

Without an atmosphere and the natural greenhouse effect, Earth’s average global temperature would be around freezing. When considered in this context, the greenhouse effect is a physical phenomenon on which human life and civilization and other forms of life as we know it depend. The greenhouse effect is due to the presence of carbon dioxide, water vapor, and a few other chemicals in the atmosphere (i.e., GHGs). In the manner of a greenhouse, these chemicals help trap heat and thus keep Earth’s temperature within a life-sustaining range. The problem is that human activities such as burning fossil fuels in power plants and automobiles, clearing tropical forests, and operating modern agricultural systems have produced additional GHGs that are accumulating in the atmosphere and generating additional global warming (see figure 1.5).

Figure 1-5 Annual global temperature anomaly (NASA GISS) and CO2 levels from ice cores at Law Dome, Antarctica (ORNL CDIAC), and atmospheric measurements at Mauna Loa, Hawaii, U.S. (NOAA)

To better understand the nature of this accumulation and its potential impacts, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) “to provide the world with a clear scientific view on the current state of climate change and its potential environmental and socio-economic consequences.”18 The IPCC is an international group of over a thousand scientists who review and summarize climate science and issue periodic reports. These reports represent the consensus of these scientists as to the best knowledge we have about climate change. The IPCC, in their 2014 reports, states the following:

Human influence on the climate system is clear, and recent anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases are the highest in history. Recent climate changes have had widespread impacts on human and natural systems. . . . Continued emission of greenhouse gases will cause further warming and long-lasting changes in all components of the climate system, increasing the likelihood of severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems. Limiting climate change would require substantial and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions which, together with adaptation, can limit climate change risks. These conclusions demonstrate that there is a global problem in both cause and effect.19

The Local Problem

Climate change is a global problem, but the impacts of climate change will be felt locally through disruptions of traditional physical, social, and economic ways of life. In some cases, these changes may be positive, such as the lengthening of growing seasons in midlatitudes, but in most cases, they will be negative. In 2018, the U.S. Global Change Research Program released its Fourth National Climate Assessment, which summarizes the impacts of climate change on the United States. The key findings of the report include the following:

- 1. Communities

Climate change creates new risks and exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in communities across the United States, presenting growing challenges to human health and safety, quality of life, and the rate of economic growth.

- 2. Economy

Without substantial and sustained global mitigation and regional adaptation efforts, climate change is expected to cause growing losses to American infrastructure and property and impede the rate of economic growth over this century.

- 3. Interconnected Impacts

Climate change affects the natural, built, and social systems we rely on individually and through their connections to one another. These interconnected systems are increasingly vulnerable to cascading impacts that are often difficult to predict, threatening essential services within and beyond the Nation’s borders.

- 4. Actions to Reduce Risks

Communities, governments, and businesses are working to reduce risks from and costs associated with climate change by taking action to lower GHG emissions and implement adaptation strategies. While mitigation and adaptation efforts have expanded substantially in the last four years, they do not yet approach the scale considered necessary to avoid substantial damages to the economy, environment, and human health over the coming decades.

- 5. Water

The quality and quantity of water available for use by people and ecosystems across the country are being affected by climate change, increasing risks and costs to agriculture, energy production, industry, recreation, and the environment.

- 6. Health

Impacts from climate change on extreme weather and climate-related events, air quality, and the transmission of disease through insects and pests, food, and water increasingly threaten the health and well-being of the American people, particularly populations that are already vulnerable.

- 7. Indigenous People

Climate change increasingly threatens Indigenous communities’ livelihoods, economies, health, and cultural identities by disrupting interconnected social, physical, and ecological systems.

- 8. Ecosystems and Ecosystem Services

Ecosystems and the benefits they provide to society are being altered by climate change, and these impacts are projected to continue. Without substantial and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, transformative impacts on some ecosystems will occur; some coral reef and sea ice ecosystems are already experiencing such transformational changes.

- 9. Agriculture and Food

Rising temperatures, extreme heat, drought, wildfire on rangelands, and heavy downpours are expected to increasingly disrupt agricultural productivity in the United States. Expected increases in challenges to livestock health, declines in crop yields and quality, and changes in extreme events in the United States and abroad threaten rural livelihoods, sustainable food security, and price stability.

- 10. Infrastructure

Our Nation’s aging and deteriorating infrastructure is further stressed by increases in heavy precipitation events, coastal flooding, heat, wildfires, and other extreme events, as well as changes to average precipitation and temperature. Without adaptation, climate change will continue to degrade infrastructure performance over the rest of the century, with the potential for cascading impacts that threaten our economy, national security, essential services, and health and well-being.

- 11. Oceans and Coasts

Coastal communities and the ecosystems that support them are increasingly threatened by the impacts of climate change. Without significant reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions and regional adaptation measures, many coastal regions will be transformed by the latter part of this century, with impacts affecting other regions and sectors. Even in a future with lower greenhouse gas emissions, many communities are expected to suffer financial impacts as chronic high-tide flooding leads to higher costs and lower property values.

- 12. Tourism and Recreation

Outdoor recreation, tourist economies, and quality of life are reliant on benefits provided by our natural environment that will be degraded by the impacts of climate change in many ways.20

These changes will vary regionally, so each community will experience a different mix of types and severities of impacts.

Some states have prepared similar analyses of the risks presented by climate change to assist communities in more clearly understanding their own risks. For example, Alaska identified problems such as melting glaciers, rising sea levels, flooding of coastal communities, thawing permafrost, increased storm severity, forest fires, insect infestations, and loss of the subsistence way of life as animal habitat and migration patterns shift and as hunting and fishing become more dangerous with changing sea and river ice.21 South Carolina is concerned that climate change is a “threat-multiplier that could create new natural resource concerns, while exacerbating existing tensions already occurring as a result of population growth, habitat loss, environmental alterations and overuse.”22 In California, the combined effects of increased drought, wildfires, and floods and rising temperatures and sea levels could result in “tens of billions per year in direct costs, even higher indirect costs, and expose trillions of dollars of assets to collateral risk.”23

At the local level, cities and counties are identifying their climate risks and developing adaptation strategies. For example, Chicago identified more intense heat waves and responded with changes to the building code, an aggressive tree-planting program, and a revised emergency response plan. Miami-Dade County, Florida, at an average of only 1.8 meters above sea level, has identified sea-level rise as a current problem that will only get worse and has established Adaptation Action Areas for planning and implementation.24 Aspen, Colorado, is worried about economic impacts to its world-famous ski resorts. The ski season is predicted to start later and end earlier, with a decreased ability to make and maintain snow during the season.25 For each of these communities, the local problem is very real and provides enough justification to act.

The Need for Solutions beyond the Local Level

Some aspects of emissions reduction and climate change adaptation require action at larger scales. The connected nature of materials flows (including global trade), economic markets, and information results in the need for governmental mandates on national and international scales. These policies level the playing field to alleviate the potential loss in competitive advantage by unilaterally enacting local climate policy. These larger-scale strategies also provide context for local efforts by addressing those emissions sources that fall outside local jurisdictional control.

The most widely recognized of the international efforts to address climate change is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Created in 1992, the UNFCCC now has 197 country signatories who have committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and acting on climate change. The history of the UNFCCC is complex, but a number of notable milestones have occurred. The first was the Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997. The protocol defined GHG emissions reduction targets and outlined a series of strategies to reach them, most of which are market-based mechanisms, including a cap-and-trade or emissions-trading system. The emissions reduction target, which varied slightly by participating country, averaged 5% below 1990 emissions levels by 2012. This target has been used as the basis for many local climate planning efforts. In addition, Kyoto signatories were required to measure or inventory their emissions and identify strategies to reduce them. The Kyoto Protocol has resulted in an overall reduction in emissions, but these reductions are not uniformly distributed among participating countries or emissions sectors.26 Between 1990 and 2007, GHG emissions had dropped in some countries, but not in all. There is similar variation among emitting sector and type of GHG. Carbon markets have proved effective for curbing manufacturing emissions but have not resulted in reduced emissions from transportation or energy sectors.

In December 2015, after numerous failed attempts to establish a post-Kyoto agreement, 195 nations—including the U.S.—reached consensus on the Paris Agreement. The basis of the Paris Agreement is a goal of limiting the global average temperature increase to below 2°C and ideally 1.5°C. National governments will achieve this goal by making commitments (called “nationally determined contributions”) to take certain actions and achieve certain reductions over time. The Obama administration signed the Paris Agreement and made a commitment to reduce GHG emissions to 26–28% below 2005 levels by 2025, but in 2017, President Trump announced his intention to remove the U.S. from the Paris Agreement.

At the national level in the United States, legislative acts, executive orders, court decisions, and agency rule making have defined the nation’s climate change policy. Perhaps most notable have been the decision by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to consider carbon dioxide a pollutant to be regulated, the Clean Power Plan, rule making on automobile efficiency and gas mileage standards, and the failure of Congress to pass a cap-and-trade bill that would further regulate GHG emissions from big industries and utility providers. On climate adaptation, little federal policy direction exists, but President Obama created the Interagency Climate Change Adaptation Task Force to provide recommendations to his administration on this issue. The bottom line is that the U.S. federal government has been doing little on climate change, and the current administration has further reduced federal action in this area.

State-level actions are too numerous to list here. According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 10 states have carbon pricing (mostly cap-and-trade), 20 have GHG emissions reduction targets, 34 have climate action plans, and 21 have climate adaptation plans. In addition, 26 states have renewable portfolio standards (RPS), which require utilities to produce a certain portion of their electricity from renewable sources.27 Communities should consult state agencies when doing their own local planning; they may provide information or the opportunity for multiscale coordination of climate action.

These international, national, and state-level actions affect local communities, so it is important that they are considered when developing emissions reduction and climate adaptation strategies. Legislative actions or government programs that increase fuel efficiency, increase renewable energy, incentivize energy-efficient buildings, or mitigate natural hazards provide a foundation on which local climate actions may build.

The Need for Local Solutions

Although solutions for climate change are needed at all levels of government, there is a clear need for action at the local level. Globally, cities consume 75% of the world’s energy and emit 80% of the GHGs.28 These emissions come from the cars and trucks we drive; the houses and buildings we heat, cool, and light; the industries we power; and the city services on which we depend. The impacts of climate change will be felt most severely at the local and regional levels as cities become threatened by rising sea levels or increased risk of flood, drought, or wildfire, for example. Changing the way we build and operate our cities can reduce GHG emissions and make cities more resilient against the impacts of climate change.

Several studies have shown the necessity of action at the local level to reduce GHG emissions. In a study of the Puget Sound region of Washington State, researchers determined that an aggressive set of assumptions about future mandated state or national fuel-efficiency standards (a 287% increase in fleet-wide fuel economy) would still require actions to reduce the number of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by 20%.29 Reducing VMT is largely a function of land use planning and alternative transportation availability, which are mostly controlled by local governments. In another study, researchers showed that to reach necessary GHG emissions reductions in the United States, part of the reduction must come from a decrease in “car travel for 2 billion, 30-mpg cars from 10,000 to 5,000 miles per year” and a cut in “carbon emissions by one-fourth in buildings and appliances projected for 2054.”30 These reductions can come from local communities reducing VMT and requiring that new buildings meet strict energy codes and existing buildings be upgraded.

In the United States, local governments have primary control over land use, local transportation systems, and building construction. Each of these areas is a critical component of climate action planning. Of course, most communities already have plans, policies, and programs that address these issues. For them, climate change is perhaps a new motivation or provides a different approach for pursuing good community planning.

Regardless of the specific purpose or variation of local climate action planning, it is an acknowledgment of the local responsibility for addressing part of the climate change problem (see box 1.5). In fact, one could argue that cities are leading the way in the United States. Federal and state action has been slow to emerge, but many cities are well into implementation of climate action and already helping solve the global problem and ultimately their own local problems.

Why Do Local Climate Action Planning?

We offer eight possible reasons for local climate action planning. Communities may acknowledge all or some of them, and there are likely additional reasons:

- • Global leadership: Communities acknowledge an ethical commitment as a global citizen to help solve the climate change crisis.

- • Energy efficiency: Communities want to increase energy efficiency and save money.

- • Green community: Communities want to create a sustainable or green image for the community, possibly to promote tourism or economic development.

- • State policy: Communities want to be consistent with state policy direction, sometimes due to incentive programs or looming mandates.

- • Grant funding: Communities want to gain access to funding that depends on having climate action policies and programs in place.

- • Strategic planning: Communities want the opportunity to organize disparate sustainability, green, and environmental policies under one program for ease of management and implementation.

- • Public awareness: Communities want to raise public awareness of the climate change issue and build support for more ambitious future efforts.

- • Community resiliency: Communities that have recognized their vulnerability to the impacts of climate change are seeking greater resilience.

What Is Happening in Climate Action Planning?

Climate action planning is occurring all over the United States in a wide variety of communities. As noted earlier, there are over 200 U.S. cities and counties committed to climate action. The communities doing climate action planning are a diverse bunch and defy the typical stereotypes of liberal or green. They range from small towns to global cities and include communities in all four U.S. regions and nearly every state. They are places varying from Des Moines, Iowa, a Midwestern city known for its financial sector and majestic state capitol, to Atlanta, Georgia, a major metropolis that is a hub of the economy in the southeast U.S. and the birthplace of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement. They include San Luis Obispo, California, a small city that is home to the highly regarded California Polytechnic State University, and Charleston, South Carolina, a historic community on the Atlantic Ocean. There is no typical climate action planning community.

To further illustrate the diversity of climate action planning in the United States, four cases of local climate action planning are presented here, and chapter 9 provides in-depth examinations of seven other communities. These communities are very different from each other, but they have all decided to address the problem of climate change and create low-carbon, resilient communities. They illustrate the kinds of climate action planning under way, the level of innovation occurring in communities, and the range of challenges and opportunities present in communities.

The City of Des Moines, Iowa

Des Moines is a capital city of 217,000 people located in central Iowa along the banks of the Des Moines and Raccoon rivers. It demonstrates a Midwestern pragmatism toward addressing a global challenge in a way that makes sense to and supports the community. In 2016, Mayor Frank Cownie committed the City to reducing its energy consumption 50% by 2030 and becoming carbon-neutral by 2050. The following year, Mayor Cownie joined the Global Covenant of Mayors, committing to set targets for greenhouse gas emissions reductions, conduct a climate vulnerability assessment, and implement mitigation and adaptation measures.

The City’s focus has been on energy efficiency and includes these notable actions:

- • In 2007, the City Council adopted the Energy Efficiency and Environmental Enhancement Policy.

- • The City Council committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions 28% by 2025 in the Des Moines Strategic Plan 2015-2020-2031.

- • In 2016, the City of Des Moines became part of the City Energy Project.

- • The City of Des Moines is leading by example by

- ◦ benchmarking energy use in 30 of the largest and most often occupied city buildings,

- ◦ developing a municipal building energy efficiency plan to improve efficiency in underperforming buildings, and

- ◦ continuing to measure and manage energy and water efficiency for ongoing improvements.31

They have also launched the Energize Des Moines Challenge. The goal is to reduce energy and water consumption in the nearly 900 buildings greater than 25,000 square feet. Building owners and managers who choose to participate in the challenge must benchmark their energy use, identify and implement energy conservation measures, and report progress. Participants receive technical support from the Energize Des Moines team and the utility provider MidAmerican Energy. This is good for the City’s goals and good for businesses’ bottom lines.

The City has also established the Citizens’ Taskforce on Sustainability to engage the community and advise the City on issues of climate change and the broader issue of sustainability. They have partnered with organizations such as 1000 Friends of Iowa, Greater Des Moines Habitat for Humanity, Iowa State University, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Neighborhood Association. They have supported the City in its launch of a climate action planning process.

The City of Atlanta, Georgia32

Atlanta is a capital city of 420,000 at the center of a metro region of over 6 million. The City has followed an uneven path toward climate action as it learned more about itself and the best way to make real change. In 2010, the Atlanta Mayor’s Office of Sustainability began the process of creating a citywide climate action plan. They prepared a GHG emissions inventory, conducted stakeholders participation sessions for over 300 individuals representing a diverse set of community interests, and developed strategies in 10 action areas. In 2015, the City adopted the Climate Action Plan and set out to implement the key strategies, including several energy initiatives that began in the prior decade.

The following year, in 2016, the City became a member of 100 Resilient Cities and hired its first chief resiliency officer. The Office of Sustainability was also reorganized and renamed the Office of Resilience (under the mayor’s office). The first order of business was to collect input from more than 7,000 residents from 40 public events, conduct 25 Neighborhood Planning Unit meetings, and work with a 100-member advisory group composed of the business, faith-based, nonprofit, academic, and civic engagement communities. This incredible public participation effort resulted in the creation of the Resilient Atlanta plan, which “serves as a roadmap to better prevent and adapt the city to the challenges of the 21st century, which include extreme climate events such as major floods or heat waves, terrorist threats, and long-term chronic stresses such as income inequality, lack of affordable housing, or the effects of climate crisis.”33 Notably, the plan goes beyond just climate change and addresses a host of short- and long-term stressors for the city. In the Resilient Atlanta plan, we see the increasing integration of climate action with broader city goals. It now serves as an overarching plan for coordinating a variety of climate and energy plans and strategies such as the Climate Action Plan and the Clean Energy Atlanta plan.

The goal of the Clean Energy Atlanta plan is for city operations to achieve 100% clean energy by 2025 and community-wide 100% clean energy by 2035. There are many possible pathways to achieving the 100% clean energy goal, but all are a combination of three key strategies: consuming less electricity through investing in energy efficiency, generating electricity from renewable sources, and purchasing renewable energy credits. Atlanta has responded to opportunities to broaden climate action beyond just GHG emissions reduction; it is striving to create a low-carbon, resilient community.

The City of San Luis Obispo, California34

San Luis Obispo is a small city of 47,000 on the Central Coast of California. The City has been addressing climate change in various ways since 2006 but recently made bold decisions to accelerate climate action. In 2008, the City joined ICLEI–Local Governments for Sustainability and the following year completed its first GHG emissions inventory. In 2012, the City adopted its first climate action plan with a goal to reduce emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. In 2017, the City adopted “climate action” as a “Major City Goal” to direct policy and budgeting decisions. The plan and goal facilitated a number of actions:

- • hiring of a full-time sustainability manager

- • establishing a “green” team for implementation

- • committing to create a community choice energy program

- • updating the climate action plan

- • formalizing a partnership with the community climate coalition

The city sustainability manager is a full-time position within the city manager’s office. The responsibilities are for the overall administration, development, and management of environmental sustainability and climate action policies and programs. The location within the city manager’s office ensures that climate action is seen as a citywide initiative, not just the purview of the community development or public works departments. The City has also formed a Green Team made up of representatives from city departments to assist the sustainability manager in planning and implementation.

In late 2018, the City became a formal partner in Monterey Bay Community Power. In California, local governments may form their own collectives for purchasing energy to provide to local residents and businesses rather than having them get power from private utilities. This way they can accelerate the purchase of renewable and low-carbon energy sources faster than state mandates on the private utilities and retain greater control for local energy rates and choices. Many California communities are now doing this, and San Luis Obispo’s plan is to move quickly to 100% carbon-free electricity.

Most recently, Mayor Heidi Harmon and the city council unanimously voted to pursue a carbon-neutral goal by 2035 for the City; this is one of the most aggressive city goals in the world. The City has begun the process of updating its climate action plan to build on its numerous successes and achieve its goal of carbon neutrality. The City will partner with a community-led climate coalition to develop and implement the plan.

The City of Charleston, South Carolina35

Charleston is a midsize city of 135,000 people with a historic waterfront downtown. In October 2015, the city experienced significant flooding associated first with Hurricane Joaquin and then later in the month with a peak astronomical tide. The hurricane did not make landfall, but it dropped over 11 inches of rain in 24 hours and a total of 20 inches of rain over several days. The high tides later in the month peaked at nearly nine feet, impacting an already drenched city. The following year, in October, Hurricane Matthew swept over the city, dropping as much as 11 inches of rain, driving over six feet of storm surge, and breaching a flood wall. Currently the city averages 11 tidal flooding events per year, and this is forecasted to increase to nearly 180 events per year by 2045. Charleston is already experiencing natural disasters that have been exacerbated by climate change, and the future looks daunting, especially if hurricane intensities increase with warming oceans.

Yet the City is not discouraged. In 2016, they adopted their first Sea Level Rise Strategy and are in the process of updating it. The first strategy identified 76 actions, of which 27 are in progress. The City has begun to better educate the public on the challenge, develop better tools for monitoring and forecasting flooding, develop in a more resilient manner, and prepare for better emergency response. In addition, it is investing $235 million in improving its old, undersized flood drainage system. It has also hired its first chief resiliency officer to help guide and oversee much of the climate action work. It has worked closely with NOAA on technical studies in particular to use the NOAA Sea-Level Rise Viewer for impact assessment and scenario planning.

The City isn’t only focused on responding to the impacts of sea-level rise; it has also sought to reduce emissions through the creation of the Green Charleston Plan. The plan is truly a community effort: “All told, more than 6,000 person-hours have been dedicated to this plan by more than 800 representatives of local and regional businesses, agencies, and organizations. More than two dozen City staff members contributed their expertise. Participants were professionally and politically diverse. The process was inclusive, with newcomers continuing to join the group until the plan’s completion.”36 The plan establishes GHG emissions reduction goals of 30% by 2030 and 83% by 2050 and includes quantified reduction strategies to get to the 2030 goal.

To make all this work for everyone in the community, the City established the Resiliency & Sustainability Advisory Committee, made up of community stakeholders, to advise the city council. The City is taking the problem of climate change seriously and leveraging all available resources to develop and implement solutions.

Overview of the Book

This book describes the climate action planning process and methods for achieving low-carbon, resilient communities. The book is a practical how-to guide that directs the reader through principal steps and critical considerations. At the end is a list of additional resources on climate action planning. In the book, we advance the theory that the best climate action planning process is based on sound science, public education and outreach, recognition of global context and external constraints, and integration with existing policies and programs.

Chapter 2 lays out a framework for getting started on climate action planning, including identifying issues of community commitment and partnerships, determining costs and timing, staffing, creating a climate action team, and auditing existing policies and programs.

Chapter 3 establishes principles and practices for developing community participation methods, including the important task of educating the public about this new and challenging public policy issue.

Chapter 4 describes best practices for GHG emissions accounting and includes advice on choosing software, acquiring and managing data, developing inventories and forecasts, and establishing emissions reduction targets.

Chapter 5 focuses on a process for identifying and evaluating measures to reduce the amount of GHGs the community is emitting. The chapter includes numerous examples of how tailoring measures to particular community contexts and capabilities is the key to successful implementation.

Chapter 6 details a process for conducting a climate change vulnerability assessment, laying the foundation for eventual adaptation strategy development. The chapter addresses climate impacts, community assets, and vulnerable populations.

Chapter 7 addresses climate adaptation strategy development, shows the link between resilience and local hazard mitigation planning, and summarizes adaptation strategies commonly used to address climate impacts, including examples from communities preparing for the short- and long-term impacts of climate change.

Chapter 8 provides guidance on successful plan implementation, including timing and financing measures and monitoring outcomes.

Chapter 9 presents seven case studies that show how communities have put this all together to develop effective climate action strategies.

Chapter 10 presents our closing thoughts about the potential for local climate action planning to positively transform the way we live, work, and play.

Finally, there are two appendices that address the science of climate change and public participation.