Chapter 9

Communities Leading the Way

This chapter presents seven cases of communities that have engaged in climate action planning and are now in the process of implementing their plans, strategies, and actions. The cases are chosen for their diversity of experiences and lessons learned. They illustrate many of the principles outlined in this book and demonstrate that climate action planning is possible in all types of communities. There are enough communities around the world now acting on climate change that there is much to be learned and shared. The experiences of these communities should prove useful to other communities that are early in the planning process or struggling to achieve implementation success. Global knowledge sharing and cooperation have become the rallying cry of many mayors and city leaders.

The City of Portland and Multnomah County, Oregon, have been in the business of developing and implementing climate strategies since the early 1990s and show how to construct a successful program over the long term.

The City of Evanston, Illinois, confirms the benefits of building “social capital” in the community that creates a grassroots capability for doing community-based climate action planning.

The City of Boulder, Colorado, leads on climate action funding with their unique carbon tax on electricity and demonstrated sustained climate action in the 15 years before its adoption.

The City of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, demonstrates the power of local partnerships among public, private, and nonprofit entities to develop and implement plans.

The City of San Mateo, California, proves that when a dedicated council and staff work together with stakeholders and citizens, they can achieve significant change.

Miami-Dade County and the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact show that counties can do climate action planning and that it can be integrated into a larger regional effort for achieving sustainability.

And finally, the City of Copenhagen, Denmark, leads the world on climate action by proving that their goal of being carbon-neutral by 2025 is possible.

Communities engaging in climate action planning can look to these communities for best practices and lessons learned.

City of Portland and Multnomah County, Oregon: Integrating Equity with Climate Action1

The City of Portland, Oregon, has been a leader in climate change policy development for 25 years (see box 9.1). The City adopted the first carbon-reduction plan in the United States in 1993. Since that time, Portland has forged a collaborative relationship with Multnomah County and has revised this original plan three times (2001, 2009, and 2015). These revised plans had the benefit of learning from the successes and challenges of earlier efforts. Over the 25 years since the first plan, the city and county’s population has grown by 30% and the economy by 40%, simultaneous with a 40% reduction in GHG emissions since 1990.2 The sustained and gradual effort by Portland to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions provides critical lessons for cities that are much earlier in the climate planning and implementation process.

Portland and Multnomah County’s plans were developed through collaboration among multiple departments, local organizations, and the public. The success of Portland and Multnomah County’s efforts can be tied to the development of strong community partnerships, a commitment to the idea that climate action plans should meet a variety of community goals in addition to GHG reductions, and long-term monitoring that has allowed strategy effectiveness to be assessed.

The first plan adopted by the City of Portland in 1993 was motivated by the City’s participation in the World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere held in Toronto, Canada, in 1988 and the United Nations’ development of the Kyoto Protocol in 1992. The plan was titled Carbon Dioxide Reduction Strategy. The target established in this plan went beyond that of the Kyoto Protocol; the City aimed to reduce emissions to 20% below 1988 levels by 2010. The reductions required to reach this target were divided among five local action sectors: transportation, energy efficiency, renewable resources and cogeneration, recycling, and tree planting. The breadth, level of detail, and ease of implementation of the strategies included in this 1993 plan set the stage for the success of future plans and actions.

Monitoring and evaluation of strategy effectiveness allowed the City to identify areas of success as well as confounding factors for overall emissions reduction. The 2000 status report, Carbon Dioxide Reduction Strategy: Success and Setbacks, individually evaluated the action items in the 1993 plan. Overall, this report showed a reduction in per-capita emissions, but increases in the community-wide total indicated that the City was falling well short of the 2010 target. Evaluation of individual strategies revealed several useful lessons, particularly regarding the role of greater-than-expected growth in the population and the economy on total emissions. This information was critical to future policy development, as it indicated areas that needed policy intervention.

The 2001 plan, Local Action Plan on Global Warming, made some minor adjustments, such as changing the baseline from 1988 to 1990 and revising the goal to a 10% reduction by 2010, closer to the 7% target for the United States under the Kyoto Protocol. Overall, the plan’s organization and target areas remained the same. The biggest change was the addition of a close partnership with Multnomah County for development and implementation of the plan. Inclusion of the County allowed for explicit recognition of the regional context and formulation of direct action to address regional issues.

The 2001 plan, City of Portland/Multnomah County Local Action Plan on Global Warming, included a review of implementation success in each sector addressed in the prior plan, Global Warming Reduction Strategy (1993). The strategies included in the plans are detailed and designed to yield GHG reductions quickly. Each action has a specific, measurable outcome, which makes implementation and tracking progress possible. The 2001 plan also contained one new section focused on education and outreach that included strategies intended to ensure that community members as well as decision-makers have a clear understanding of climate science, the challenges posed by climate change, and the options for addressing these challenges. During the period following the 2001 plan, Portland and Multnomah County exhibited not only continued per-capita GHG reductions but also reductions in overall GHG emissions. By 2005, emissions in the county had been reduced to 1990 levels, and they were several percentage points below 1990 levels by 2008. As a result, the City and County were nearly on track to reach the targets set in 2001, though they are still unlikely to meet the original 1993 goal.

Implementation highlights for the City and County plan during the period between 2001 and 2009 include the following:

- • Transit ridership has increased by 75%.

- • Bicycling has quintupled, with mode share over 10% in many parts of the city.

- • Recycling rates reached 64%.

- • The City saves $4.2 million annually due to reductions in energy use (~20% of total energy costs and $38 million since 1990).

- • Thirty-five thousand housing units have been improved in partnership with utilities and the Energy Trust of Oregon.

- • Reductions in vehicle miles traveled have resulted in $2.6 billion in annual savings.3

The Climate Action Plan 2009 maintained the earlier versions’ sectors of focus, with energy efficiency and renewable energy combined into one and two additional focus areas added: preparing for climate change (e.g., climate change adaptation) and food and agriculture.

The major difference is that the 2009 plan established emissions reduction targets for the combined city and county of 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 and 80% by 2050. The 2050 target requires dramatic emissions reduction and shows the City’s commitment as a member of the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance. The plan included both short-term actions that were to yield immediate reductions in GHGs and those that will lay the foundation for the vision for 2050. One example of the long-term focus is the goal of twenty-minute neighborhoods, “meaning that they [residents] can comfortably fulfill their daily needs within a 20-minute walk from home.”4 Strategies such as this were developed through public outreach events, which were critical given the extent of changes required to meet the 2050 target. The goal of reducing emissions by 80% requires dramatic changes in energy efficiency, energy sources, and travel behavior, such as a reduction from 18.5 to 6.8 passenger miles per day.

The 80% reduction in GHG emissions below 1990 levels by 2050 target is maintained in the 2015 climate action plan. One of the biggest changes in the latest update is a strengthened emphasis on social equity and health. While both points of emphasis are mentioned in the 2009 plan, the 2015 plan builds on this focus, expanding the breadth of strategies. The City released the document Climate Action through Equity: The Integration of Equity in the Portland/Multnomah County 2015 Climate Action Plan a year later in 2016. The focus on equity includes the engagement and inclusion of underserved and underrepresented communities. This was achieved through the establishment of the Climate Action Plan Equity Working Group to aid in the identification of issues and development of strategies.

Another critical change in the 2015 plan was a consumption-based or life-cycle GHG emissions inventory (see figure 9.1). This inventory includes all the upstream GHGs emitted as part of producing products consumed, purchased, or used in the city and county. This inventory allows consumption to be assessed and for Portland and Multnomah County’s role in global GHG emissions to be more accurately understood.

Figure 9-1 Global emissions as a result of local consumer demand as reported in the 2015 Portland and Multnomah County climate action plan

Source: City of Portland and Multnomah County, Climate Action Plan (2015), https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/49989.

Lessons Learned

The Portland city and region have engaged in a long, sustained effort to develop and implement planning policy to address climate change. Over the last 25 years, the city and region have achieved some remarkable GHG reductions. Some of the factors identified by the City as keys to this success include a focus on co-benefits, the development of partnerships to aid in implementation, and the integration of climate goals into all aspects of community policy.

Co-benefits can include improved air quality and human health, economic savings, and greater convenience. These co-benefits not only aid in fulfilling a range of other community goals but also yield unexpected collaborations and garner supporters of the plan. This has continued through the recent focus on equity and a 2016 document focused on the issue, specifically assessing and demanding that new approaches address unintended consequences, including investment strategies to alleviate displacement.

Forging partnerships with community organizations is viewed by city staff as a critical component of successful implementation. Portland has collaborated more closely than many cities with such entities. Not only has it relied on them to aid in facilitating public engagement, but it has even given the responsibility of implementing some strategies to local organizations. These partnerships provide resources necessary for implementation in the form of funding, material resources, and labor. This allows the City and County to implement more of the identified strategies in a timely manner because it expands the resources available to do so.

When asked what advice they would give a community just beginning a climate planning process, Portland staff identified two basic principles. The first is to start with the easy things. Choose lots of actions that can have an immediate impact. Demonstrating effectiveness quickly can build the momentum and gather the support necessary to take on larger, more expensive, and longer-term efforts. The second piece of advice is to learn from others. In the development of the 2009 plan, Portland staff read through the climate action strategies developed by other cities. The plan developers then repaid those from whom they learned by transparently reporting on the implementation progress of their most recent plan. The 2017 Climate Action Plan Progress Report not only keeps all participants in plan implementation accountable but also serves to build community support by demonstrating ongoing progress and provides lessons for other communities with similar aims.

Figure 9-2 The Portland and Multnomah County climate action plan, which identifies over 170 actions to be completed or significantly under way by 2020. The 2017 progress report indicates good progress on nearly 90% of the strategies identified.

Source: City of Portland and Multnomah County, Climate Action Plan (2015), https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/49989.

City of Evanston, Illinois: Empowerment from the Grassroots5

To the citizens of the City of Evanston, Illinois, the decision to engage in climate action planning was the obvious and right thing to do (see box 9.2). The community has a long history of having an active and engaged citizenry who see the issue of sustainability as a key to a better future. Leaders in city hall recognized that waiting for the federal government to solve the problem was neither sufficient nor likely and that local action could be meaningful and effective.

In the late 1990s, a group of citizens interested in sustainability and the role of the faith community formed the Interreligious Sustainability Project. They held numerous public forums to present and discuss sustainability ideas, and they sought to build a network of interested citizens. This is often referred to as building social capital. The citizens of Evanston weren’t organizing to specifically address climate change or any particular environmental issue at all. Instead, they were laying the groundwork for future action by educating, inspiring, and networking. This social capital paid dividends several years later with the formation of the Network for Evanston’s Future. With the community coalescing under the group, the city government began the initial steps for climate action planning. In 2006, the Evanston city council voted unanimously to sign the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement, and state representative Julie Hamos committed some of her discretionary funds to support an Office of Sustainability in the mayor’s office. With the City on board and the Network for Evanston’s Future organizing the volunteer labor, Evanston was positioned to engage in climate action planning.

In 2008, the community completed the first Evanston Climate Action Plan; built on a cooperative effort among community organizations, businesses, religious institutions, and government, it showcased what communities can do when they come together to take responsibility for their actions and plan for a better future. Creation of the plan involved organizing these motivated citizens into teams to assist in inventorying the city’s GHG emissions, developing potential strategies to reduce these emissions, and compiling them into a guiding document that could be successfully implemented. The mayor of Evanston, Elizabeth Tisdahl, described this as a “wonderful process.” The wonder of Evanston was the community’s ability to build coalitions of organizations and volunteers through a truly grassroots effort that was not controlled by city hall.

Over the next decade, the City updated the plan and GHG emissions inventory, released periodic progress reports, adopted the Evanston Livability Plan, and joined the Global Covenant of Mayors. In 2018, the City adopted the Evanston Climate Action and Resilience Plan, which establishes a goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. Other goals of the plan include the following:

- • achieving 100% renewable electricity for all Evanston accounts by 2030

- • achieving a 50% reduction in emissions by 2025 and an 80% reduction by 2035

- • diverting 100% of waste from landfills (zero waste) by 2050

- • securing 100% renewable electricity for municipal operations by 2020

- • reducing vehicle miles traveled to 50% below 2005 levels by 2050 while increasing trips made by walking, bicycling, and public transit6

In addition to GHG emissions reduction, the 2018 Evanston plan for the first time addresses climate impacts. It contains numerous actions in six areas:

- • green infrastructure

- • health impacts of extreme heat

- • resilience regulations

- • community networks and education

- • emergency preparedness and management

- • vulnerable populations

All these strategies are evaluated through the lens of Evanston’s three core guiding principles: equity-centered, outcome-focused, and cost-effective and affordable.

Figure 9-3 Expected climate change impacts to the community of the City of Evanston, Illinois

Source: “Climate Change in Evanston,” City of Evanston, https://www.cityofevanston.org/government/climate.

Evanston’s planning has resulted in three notable actions. First, the City is leading by example by adopting aggressive municipal operations goals:

- • 2020—100% renewable electricity for municipal operations

- • 2030—achieve zero waste for municipal operations

- • 2035—carbon neutrality for municipal operations

To achieve these goals, the City has identified 27 strategies, including for example, installing LED lighting, achieving net-zero emissions municipal buildings, transitioning to a zero-emissions fleet, planting trees, diverting construction waste, and advocating for state and national carbon markets.

Second, the City has secured commitments in the plan for climate action from leading employers in the city. For example, Northwestern University has adopted a net-zero emissions goal and Presence Saint Francis Hospital has committed to reducing GHG emissions levels 50% by 2025. The City has recognized that it cannot achieve its goals acting alone; it must have these partnerships with other leading entities in the community.

Third, the City’s resiliency strategies are linked to public health services and emergency management. Agencies, companies, and organizations operating in these fields have a wealth of resources and knowledge on how to solve health and disaster problems. Evanston has wisely linked climate change with these other community challenges in its goal to build resilience. It is leading a new international movement to shift resilience thinking beyond just the issue of climate change and to include issues of social, economic, and environmental justice:

The adoption of Evanston’s Climate Action and Resilience Plan continues the City’s leadership on climate and environmental issues. Since 2006, with the signing of the U.S. Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement, Evanston has achieved certification and recertification as a 4-STAR sustainable community, been named the World Wildlife Fund’s 2015 U.S. Earth Hour Capital, joined the Global Covenant of Mayors, and served as a founding member of the Mayors National Climate Action Agenda (MNCAA). In 2017, Mayor Hagerty joined municipal leaders from across the world in signing the Chicago Climate Charter, pledging to uphold the commitments of the Paris Climate Agreement. The mayor has also committed to the Sierra Club’s Mayors for 100% Clean Energy initiative, supporting a communitywide transition to 100 percent renewable energy.7

Lessons Learned

Evanston citizens felt like they could not wait for the state or federal government to take steps to alleviate the climate change problem. Before doing formal planning, they built social capital and collaborations, called on organizations already doing good climate action work, and began to build the political will in the community. They then organized and educated themselves and showed that motivated citizens, with support from city hall, can successfully engage in climate action planning.

The Evanston plan has many strategies that will be implemented by entities within the community, such as businesses, nonprofit organizations, and community groups. It is not clear at this point where the resources will come from to implement these strategies or how these entities can be held accountable. When depending on community-based entities rather than government agencies, there should be significant discussion of these implementation issues.

City of Boulder, Colorado: Innovative Financing for Implementation8

Boulder, Colorado, presents a different path in addressing climate change (see box 9.3). The City implemented programs to reduce GHG emissions for over 15 years without a formal climate plan. The City passed a resolution matching the terms of the Kyoto Protocol in 2002. This target served as the guiding aim for the next decade. The sustained progress, ongoing community support, and demonstrated effectiveness mean that Boulder can provide lessons to communities devising their approach to climate action.

In 2002, the City of Boulder’s city council passed the Kyoto Resolution, which aimed to lower GHGs to 7% below 1990 levels by 2012. An inventory of local emissions was completed four years later, in 2006. A year after that, the City passed the nation’s first voter-approved tax dedicated to addressing climate change, the climate action plan tax (CAP tax). The tax is levied on city residents and businesses based on the amount of electricity consumed. The CAP tax generates $1.8 million a year to be spent on programs, services, and incentive rebate programs in homes and businesses. Thus far the tax has raised $17.3 million to support climate action. It has worked. Boulder reports a 16% reduction in GHG emissions since 2005; over the same period, the city gained 7,500 more jobs and saw a 57% increase in gross domestic product.9 Boulder voters approved a continuation of the tax in 2015, extending it to March 2023.

Over the last 10 years, Boulder has implemented many programs and strategies. The list below provides four such examples, but it is not exhaustive. Measures pursued by the City cover nearly all aspects of climate action, focused specifically on GHG emissions reduction from all sectors:

- • 2011 SmartRegs Ordinance: Boulder directly sought to affect one of the most difficult building types to address in any city, rental units. The city council adopted a SmartRegs Ordinance requiring energy performance in rental properties.10 The ordinance set minimum energy efficiency standards for all rental properties (single and multifamily) to be met by 2019. In January 2019, rental properties had to prove compliance with SmartRegs to obtain new rental housing licenses, and noncompliant existing licenses expired.11

Adopted in 2011, the ordinance afforded an eight-year period for rental property owners to comply. It was supported by three incentive or rebate programs to help owners and managers of rental properties: EnergySmart provided advice and access to funds for home energy and electric vehicle upgrades; the Water Conservation program provided assessment, low-cost upgrades, and incentives for water-use-reducing measures; and Excel Energy Incentives provided motivation for energy audits and for lighting, heating, and cooling upgrades.

- • 2013 Energy Conservation Code: First adopted in 2013 and updated in 2017, the City’s building codes require new and remodeled residential and commercial buildings to meet net-zero emissions by 2031.12 These codes build on international low-carbon building standards such as the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) and the GreenPoints program. The City conducted outreach, identified challenges with both programs, and devised an update to the building code to streamline the process and make the 2017 code even stronger from a GHG-emissions-reduction perspective.

- • 2014 Marijuana Renewable Energy Offset Requirement: In 2014, the State of Colorado legalized cannabis for both medical and recreational use. The Marijuana Renewable Energy Offset Requirement addresses the fact that the lighting and cooling systems that are used to grow marijuana plants indoors have been shown to disproportionately increase electricity consumption and associated GHG emissions. This offset asks marijuana facility owners to meet two requirements: to track energy use using the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy STAR portfolio manager (an online tool) and to prove that 100% of the energy used is offset using one or a combination of four methods, including renewable energy on site, participation in a verified solar garden, participation in one of Excel Energy’s renewable energy programs, or offsets purchased through Excel Energy.13

- • 2015 Universal Zero Waste Ordinance: Boulder currently diverts 40% of its waste from a landfill (through recycling and composting) with an aim to move that number up to 85% by 2025. The Universal Zero Waste Ordinance has several requirements to support this aim, including the following: all single-family homeowners must subscribe to waste hauling, businesses must provide clearly marked receptacles for recycling and compost, and composting and recycling must be provided at all special events in the city.14

Boulder did not adopt a formal plan until 2017 with the release of Boulder’s Climate Commitment. This plan is organized around four areas of action, and there are three sectors for each action area. For example, the energy action area includes buildings, mobility, and electricity. For each subsection, there are measures identified as “2017 to 2020 City Action Priorities.” These short-term strategies are one way for the City to continue its success in implementing change and climate action. Further ensuring success, each section also identifies indicators to track progress and target dates for completion. Another critical aspect of the plan is a listing of supportive partnerships for each strategy subsection.

Beyond the measure-specific partnerships, the City of Boulder has pursued collaborative relationships both externally and internally. By joining the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance, Boulder became part of a community of 20 cities from all over the world pursuing 80% to 100% GHG reduction by 2050. Having shared goals allows for information sharing that covers innovative approaches, strategies for overcoming barriers, and other lessons learned. Within the city, Boulder seeks ways to ensure that its climate actions are well understood and address the needs of all parts of the community. BoulderEarth is a coalition of local nonprofits in partnership with the City that aims to inspire community action to address climate change and to support community engagement and input. The coalition keeps a calendar of community events—publicizing activities from local hikes, to speakers, to public hearings—and collects data to better understand local needs, concerns, and questions.

The CAP tax in Boulder is set to expire in 2023, and funding obtained from the local electrical utility will expire as well if the City successfully implements a city-owned electric utility, which would leave a $4.4 million shortfall each year if the City intends to meet the aggressive targets for GHG emissions reduction they have set. As a result, the City is considering a tax on new vehicles, called a vehicle registration efficiency tax. This is projected to alleviate all but $1.1 million of the projected shortfall. The City-owned electric utility may replace some of what Excel Energy provided, but it will not be generating revenue until at least 2024.15 Boulder is a great lesson for communities with aspirations of aggressive climate policy, as they have creatively and effectively found ongoing ways to fund their strategies and engage the community.

Lessons Learned

Boulder’s Climate Commitment states, “We need to change the system, not just the light bulbs.” This commitment began in 2002 with the City’s first formal action regarding climate change with the passage of the Kyoto Resolution, which committed Boulder to lowering GHG emissions 7% below 1990 levels by 2012. Since that time, Boulder has exemplified its commitment to ongoing, iterative implementation of climate goals with repeated updates, monitoring, and assessment, followed by even more new or updated strategies. This approach was not dependent on a climate plan; it was simply a comprehensive city goal. Boulder’s Climate Commitment (the City’s climate action plan) was adopted in 2017, 15 years into the City’s pursuit of climate goals.

Ongoing pursuit of climate action strategies has led to the development and subsequent bolstering of many strategies. In several cases, Boulder is currently pursuing measures that would have been unthinkable 10 to 15 years ago but are now treated as an acceptable, even desirable, next steps given the ongoing efforts and commitments of the City. These include the following:

- • “Decarbonize, Democratize, and Decentralize”: Boulder has long pursued energy efficiency and adjustment to more renewable energy sources but now is pursuing community choice energy. Another critical and instructive aspect of this goal is that Boulder already has a backup plan that recognizes the need to keep improvising, adjusting, and moving forward: “If this effort is not successful, the city will redirect its efforts to partner with the current electric utility and/or explore other options.”16

- • Buildings: Already, the City has reduced building emissions by over 40% since 2010. Building on these achievements, the City is partnering with the county, the University of Colorado–Boulder, and the local school district to pursue strategies targeting rental and multifamily units as well as to implement net-zero building codes, with an aim toward all new buildings achieving net-zero energy by 2031.

- • Transportation: Boulder set an initial goal of holding the 1996 VMT level steady as the city grew. That goal has been achieved despite other communities in the Colorado Front Range experiencing continued growth in community VMT. No longer satisfied with holding VMT steady, Boulder now seeks overall reductions in transportation-generated GHG emissions. Similar to other focus areas, these goals will be achieved through several complementary measures, including an expanded transit program, increased ride-sharing, and a greater emphasis on bike and pedestrian transportation. Further supporting these actions, Boulder is pursuing various efforts to increase the number of electric vehicles used in the city.

While all the strategies are laudable, the other aspect of Boulder’s approach to climate action planning that should be imitated is the focus on consistent funding to support these efforts. None of these efforts could be implemented without funding and staff. Boulder’s CAP tax continues to provide funding to support climate action strategies. As mentioned above, the City continues to keep an eye to the future and plan ways to raise the required funds to support their ambitious climate aims.

City of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Power of Partnerships17

The 2018 Pittsburgh Climate Action Plan is the third plan by the City and continues to involve and rely on grassroots community effort and engagement rather than being a product exclusively of the municipal government (see box 9.4). Pittsburgh’s initial climate action planning process was community initiated and catalyzed by several organizations. In 2006, the Green Building Alliance, with then mayor Bob O’Connor, convened the Green Government Task Force of Pittsburgh to begin discussions of addressing sustainability and climate change. At the same time, the Green Building Alliance partnered with Carnegie Mellon University students and faculty to develop the City’s first GHG emissions inventory. In addition, the Surdna Foundation, a private grant-making foundation, helped bring in and fund the nonprofit Clean Air–Cool Planet to provide technical expertise and write the plan. The city government was a partner in the process but did not take the lead or an oversight role. In Pittsburgh, climate action planning was a stakeholder-based process to produce a plan with investment from all sectors.

The Pittsburgh Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory was completed in 2006 by a student and faculty research team from the Heinz School at Carnegie Mellon University. The baseline year for analysis was 2003 because this was the earliest year for which complete data were available. The City emitted about 6.6 million tons of CO2e GHGs in 2003. The plan established a GHG emissions reduction target of 20% below 2003 by 2023 that was based on a review of peer communities and the task force’s feasibility discussions. Another inventory was completed in 2013 and used as the basis for the 2018 plan, which includes new plans for annual updates of inventory data.

In 2012, the Pittsburgh Climate Action Plan 2.0 was developed to review and revise the greenhouse gas emissions reduction efforts identified in the first plan and propose new measures that could be implemented to meet a greenhouse gas reduction target of 20% below 2003 levels by 2023. These targets were further bolstered and extended in the 2018 Pittsburgh Climate Action Plan 3.0. The 2018 plan has targets that align with those of the Paris Agreement: an 80% GHG emissions reduction below 2003 levels by 2050 and a companion goal of future carbon neutrality.18 Two additions to the 2018 plan include a greater focus on local sustainability and resilience and new strategies centered on sequestration. With the creation of this plan, the community group that had been instrumental in the last two plans, now termed the Pittsburgh Climate Initiative group, reconvened, continuing the strong collaboration between the City and the community.

The Pittsburgh Climate Action Plan 3.0 is organized into six sectors: energy generation and distribution, buildings and end-use efficiency, transportation and land use, waste and resource recovery, food and agriculture, and urban ecosystems. Development of the plan built on past success in its reliance on residents and community organizations, citing over 400 residents representing 90 organizations from the Pittsburgh business community, nonprofit sector, and local, state, and federal government partners. For each sector, goals, objectives, strategies, challenges, existing projects and previous work, and champions are identified. This level of detail and context and the full support of community partners illustrate a community vision and path forward that should lend confidence to future implementation effectiveness (e.g., see box 9.5).

In 2015, Pittsburgh was named one of the 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation.19 The following year, the City named a chief resilience officer, who heads the new city department of Sustainability and Resilience. Pittsburgh was identified in 2018 as one of 20 cities that would receive a large monetary award ($70 million) as part of the Bloomberg American Cities Climate Challenge to support a two-year accelerated implementation program to reduce GHG emissions.20 In addition, Pittsburgh has also received several grants and established partnerships to support the implementation of other parts of the plan, including $250,000 in funding from the Alternative Fuels Incentive Grant Program (AFIG) run by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection.21

Lessons Learned

In Pittsburgh, strong leadership from the mayor and the formation of a community-based leadership group were important first steps in creating a climate action plan, and the City has maintained its reliance and collaborative relationship with the citizens and community groups that fostered the initiation of its climate action strategy development. These community leaders represented a diverse set of important sectors in the Pittsburgh economy. Forming this type of coalition of local partners built broad support for the plan and ultimately improved the quality of the plan.

Pittsburgh took a unique approach to implementation by assigning it to a new city department of Sustainability and Resilience, which can focus on and coordinate the varied strategies in the plan. To complement this department, each sector of the plan identifies critical collaborators and local champions, maintaining the close relationship between the City and the community.

Finally, Pittsburgh has already identified a projected time frame for development of climate action plan 4.0. Each iteration of the plan is stronger, more aggressive, and more integrative. This progress and explicit recognition of the ongoing process of implementation maintain community involvement, local commitment, and municipal staff commitment.

City of San Mateo, California: A Comprehensive Approach to Climate Action22

San Mateo is located south of San Francisco in Silicon Valley and is home to about 103,000 residents but is within a metropolitan area of nearly 2 million (see box 9.6). The City boasts a historic downtown and vibrant economy and is supportive of economic growth, infill, and mixed-use development. The City has a long-standing commitment to environmental stewardship and sustainability and was an early advocate of climate action planning. The City adopted its first sustainability plan in 2007 and has been working steadily to implement sustainable practices in its municipal operations and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions community-wide.23 From 2005 to 2017, the community’s GHG emissions decreased 18% while the City grew its population by 11% and increased jobs by 54%.24

The City’s success in decreasing GHG emissions, expanding sustainability practices, and conserving natural resources can be attributed to long-standing commitments by the community and the city council in addition to a dedicated team of City staff and regional partnerships. The City considers itself to be “a progressive community that continuously considers the impact that today’s actions will have on future generations. This is why sustainability is a top priority of the City. It is our goal to preserve the environment, provide economic well-being, and ensure social equity for our residents and businesses.”25

The City has codified its sustainability goal through its environmental and land use planning processes, codes and ordinances, and funding commitments. The City adopted its first green building code in 2010. In 2013, the City adopted ordinances banning polystyrene containers in city restaurants and food stores and prohibiting single-use plastic bags in the city. The City was one of the first communities in California to integrate climate action into its comprehensive planning process. They have adopted and implemented many plans to increase mobility through alternative modes, including a Pedestrian Master Plan, a Bicycle Master Plan, a Sustainable Streets Plan, a Safe Routes to School program, and an Active Transportation Plan. The City’s general plan promotes infill, mixed-use, and transit-oriented development.

The City’s 2030 general plan, adopted in 2010, included the City’s vision to be an environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable city and included goals and policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, a greenhouse gas emissions reduction implementation program based on the Sustainable Initiatives Plan adopted in 2007, and direction that all future development address climate change in accordance with the general plan. The general plan directed the City to reduce GHG emissions to 15% below 2005 levels by 2020, 35% below 2005 levels by 2030, and 80% below 1990 levels by 2050. At the time of adoption, the State of California’s adopted statewide GHG reduction target was to reduce emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, which the State translated to be approximately equivalent to 15% below 2005–8 levels by 2020 for local government.

In 2014, the city council created a full-time sustainability coordinator staff position within the city manager’s office to coordinate and expand the City’s sustainability efforts. The sustainability coordinator position is funded by the City’s general fund and has an allocated annual budget to implement new community-wide programs and projects in addition to capital projects, including energy retrofit projects, funded through the City’s Capital Improvement Program, loans, and partnerships.

The City of San Mateo formed a sustainability commission in May 2014, which was renamed the sustainability and infrastructure commission in 2018. The commission is composed of five San Mateo residents appointed by the city council and is charged with making recommendations to the city council on policies and programs related to the long-term environmental, economic, and social health of the City. The first task assigned to the Sustainability Commission was to update the General Plan 2030 Greenhouse Gas Reduction Plan, later renamed the Climate Action Plan (CAP). Since the adoption of the CAP, the sustainability commission has supported implementation.26 The commission’s work plan includes serving in an advisory role to staff during the implementation and update of the climate action plan.

In 2014, the City hired a consultant to prepare a climate action plan in partnership with city staff and the community, guided by the newly designated sustainability coordinator, the newly appointed sustainability commission, and community stakeholders. In April 2015, the city council adopted the CAP to serve as the City’s comprehensive community-wide strategy to reduce GHG emissions to achieve the 2020, 2030, and 2050 reduction targets adopted in the 2030 general plan.

Many of the City’s GHG reduction measures rely on the city government to initiate and lead implementation. As such, interdepartmental engagement was essential in the development of the CAP to ensure that goals and strategies were attainable and appropriate for each responsible department. The City formed a CAP technical advisory committee (TAC) to support the consultant’s and sustainability manager’s review of existing programs and evaluation of new programs. The TAC included staff from multiple city departments, including public works, community development, parks and recreation, the city attorney’s office, and the city manager’s office. Drawing on the expertise of these departments helped define actions.

The City invited residents, business owners, and other stakeholders to contribute ideas and concerns throughout the CAP development process. The project team facilitated engagement outreach activities at its Concerts in the Park events, an online town hall website, and a community forum at the San Mateo Public Library. Community engagement was supported by graphics and materials that sought to present the CAP in an accessible and engaging manner (see figure 9.4). The City’s online town hall website provided ongoing open dialogue on key questions and topics important to plan preparation. In addition, all sustainability commission meetings, planning commission hearings / study sessions, and city council public hearings allowed opportunities for public comment.

Figure 9-4 The City of San Mateo’s prepared and distributed education materials, including a “What is a CAP?” poster, part of its community engagement program during preparation of the 2015 CAP

Source: City of San Mateo, City of San Mateo Climate Action Plan (2014), https://www.cityofsanmateo.org/DocumentCenter/View/44698/San-MateoCAP-PublicReviewDraft_2-23-15_Clean?bidId=.

The 2015 CAP includes 28 implementation measures organized into categories such as energy efficiency, renewable energy, alternative transportation and fuels, solid waste, wastewater, and off-road equipment. Each measure has a list of recommended actions that represents suggested means of achieving the measure but is not a prescriptive path for implementation. Each also identifies co-benefits, a lead department, a time frame for implementation, quantified GHG reductions, and beneficiaries (i.e., existing development, new development, and municipal operations).

The City has sustained implementation of the CAP since its adoption in 2015. City staff provide an annual update of implementation progress to the sustainability commission and city council. Implementation of the CAP has been cross-cutting, with projects and programs carried out by several city departments and throughout the community. The sustainability coordinator’s 2018 CAP Progress Report identified the following key highlights of the work completed since 2015:

- • Community choice energy: Peninsula Clean Energy (PCE), a community choice energy (CCE) program, completed enrollment of all electricity accounts in San Mateo County in May 2017 and became the default electricity provider for the City of San Mateo. Electricity in the city was previously provided by an investor-owned utility, Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E). PCE is a locally controlled community organization that procures electricity and provides community programs to support energy efficiency and renewable energy. PCE offers two options: ECOplus, a minimum of 50% from renewables and 90% carbon free; and ECO100, 100% from renewables and 100% carbon free. PCE intends to offer 100% GHG-free electricity by 2021, which will be sourced by 100% renewable energy by 2025. PCE also intends to create a minimum of 20 megawatts of new local power by 2025 to stimulate development of new renewable energy projects and clean-tech innovation in San Mateo County, to expand local green jobs, and to invest in electric vehicles, energy efficiency, and demand response programs. The City’s draft for its 2017 Community-Wide GHG Inventory reflected the impact of PCE on the community’s emissions, with GHG emissions from electricity use having decreased approximately 50% since 2015.

- • Streetlight retrofits: The City converted 80% of streetlights to LED bulbs—approximately 5,000 traditional streetlights to LED lights. The first phase was completed in July 2014 and consisted of the conversion of 900 cobra-head streetlights to LED lights through a turnkey on-bill financing partnership with PG&E. The second phase included the LED retrofit of 4,400 cobra-head and low-voltage decorative streetlights funded by a loan from the California Energy Commission.

- • Energy efficiency retrofits at City facilities: The City entered into a contract with PG&E for the Sustainable Solutions Turnkey program and completed an energy assessment for retrofits at major municipal City facilities. Retrofits are planned to begin in 2019.

- • Community-wide energy and water conservation and efficiency programs: The City has led or partnered in many energy and water conservation and efficiency programs with positive results.

- ◦ The City has approved several Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) financing programs—including California First, HERO, Alliance NRG, Ygrene, Figtree, and OpenPACE—to provide financing options for residents and business owners. PACE programs support energy efficiency, renewable energy, and water efficiency projects by property owners.

- ◦ In 2010, the Bay Area Regional Energy Network (BayREN) formed to provide regional-scale energy efficiency programs, services, and resources. BayREN is a collaboration of the nine counties that make up the San Francisco Bay Area, led by the Association of Bay Area Governments. BayREN is funded by California utility ratepayers under the auspices of the California Public Utilities Commission. The City partnered with BayREN to promote energy efficiency rebate programs, issuing rebates to 85 single-family homes and 887 multifamily units from 2014 to 2017.

- ◦ The City collaborated with San Mateo County to provide home energy and water-saving toolkits at San Mateo branch libraries with free supplies.

- ◦ The City participated in the Georgetown University Energy Prize (GUEP) competition from January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2016. The GUEP was a two-year-long friendly national competition among 50 small and medium-sized cities to lower energy use in the residential, municipal, and public school sectors. While San Mateo was not a GUEP finalist, the City reduced overall electricity consumption by 6.4% and gas consumption by 17.4% from 2013 usage.

- ◦ The City provided supplemental funding to El Concilio, a local nonprofit, to target energy efficiency upgrades for low-income households through the Energy Savings Assistance Program. Energy specialist ambassadors canvassed door to door for the program in both English and Spanish.

- ◦ In 2008, the City joined San Mateo County Energy Watch, which formed as a partnership between PG&E and the City/County Association of Governments of San Mateo County to provide energy efficiency services to local governments, schools, small businesses, nonprofits, and low-income residents in the county. The services provided by San Mateo County Energy Watch include no-cost energy audits, special incentives, benchmarking services, and hosted classes and trainings about energy efficiency.

- • Reach codes: The city council adopted green building and energy code amendments that require items that are above and beyond what is included in state codes.27 The City’s adopted reach codes, which went into effect on January 1, 2017, require the following:

- ◦ Mandatory EV readiness: The green building code amendment requires that one space in all multifamily buildings with 3–16 units and 10% of the parking spaces in all other multifamily and nonresidential projects be EV-ready.28

- ◦ Mandatory Laundry-to-Landscape diverter valve: The green building code amendment includes a mandate for new single-family homes to install a diverter valve to more easily allow for future gray water reuse from their laundry machines.

- ◦ Mandatory solar installations: The energy code amendment requires the inclusion of minimum-size solar photovoltaic installations for all new construction.29

- ◦ Mandatory cool roof installations: The energy code amendment requires cool roof installations for new multifamily and nonresidential projects with low-sloped roofs.

- • Bike share: The City operated the Bay Bikes bike-share program, a fleet of dockable bicycles. It grew to over 1,000 members and 8,700 unique trips. The City also currently offers a dockless fleet of bicycles and electric bicycles through a private provider at no cost to the city.

- • City-promoted infill and transit-oriented development projects: Transit-oriented projects are located near Caltrain stations and/or bus routes. Many new development projects are required to implement transportation demand management (TDM) practices to reduce vehicle trips generated by the development. Sample TDM strategies include providing free transit passes for residents or employees, paying into a shuttle program, encouraging carpooling, and providing on-site car-sharing vehicles.

- • CAP consistency checklist: All new development subject to discretionary review and the State’s California Environmental Quality Act must prepare a CAP Consistency Checklist for submittal with land use permit applications. City staff consider the project’s implementation of GHG reduction programs part of discretionary review.

Lessons Learned

The 2015 CAP provided a strategic plan to achieve the City’s 2020 GHG reduction target. The City has implemented the CAP since adoption and has seen steady reductions in emissions. The CAP included an implementation program and a commitment to monitoring, annually reporting, and updating at least every five years. The City’s success with CAP implementation can be attributed to a team of climate champions:

- • a dedicated sustainability coordinator, who has provided time and technical expertise to facilitate implementation, monitoring, reporting, and community engagement;

- • oversight by the sustainability and infrastructure commission, which provides transparency and accountability;

- • ongoing support by the city council; and

- • multiple regional partners and programs that support GHG reductions in all sectors.

The community’s achievement of its 2020 GHG reduction target is a result of its successful implementation of the CAP; its commitment to the use of its general fund and external grants and loans to fund energy efficiency retrofits, renewable energy projects, waste reduction programs, clean and alternative transportation projects and programs, and water conservation programs; and its participation in a regional community choice energy program. While the community’s conservation and efficient use of resources have contributed to its decline in GHG emissions, the community has also significantly benefited from increases in clean energy and a transition to carbon-free and renewable energy. Peninsula Clean Energy, the community choice energy program, appears to be the most impactful program to reduce local and regional GHG emissions to date.

In addition, the City, like all communities in California, has benefited from the policies and programs of recent state governors and legislatures that have prioritized and funded statewide GHG reductions in all sectors. The noticeable local benefits are from the expansion of clean fuels and the renewable energy supply.

In fall of 2018, the City initiated an update to the CAP with an expectation that the 2020 CAP will include a more aggressive 2030 reduction target than the one currently adopted and a decarbonization pathway to 2030 and beyond. Its challenges will be to sustain and increase reductions through significant decarbonization in the transportation and energy sectors.

Miami-Dade County, Florida, and the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact: Cooperating for Regional Action

Miami-Dade County, Florida, is one of the 12 original members of the ICLEI Cities for Climate Protection Campaign founded in 1990 (see box 9.7). They have a 30-year history of acknowledging and addressing the issue of climate change. When the County started, they were one of the few local governments taking action, but they realized that they could not tackle the issue alone. As more local governments in southeast Florida began climate action planning, it became clear that a cooperative regional approach would help accelerate action and enhance implementation.

In 1993, the County became one of the first communities in the world to engage in climate action planning. They developed A Long Term CO2 Reduction Plan for Metropolitan Miami-Dade County, Florida, which set a GHG emissions reduction target of 20% below 1988 levels by 2005 and identified 13 areas for emissions reduction. Also, it notably called on the state and federal governments to adopt measures to improve vehicle gas mileage and energy conservation.

In 2006, the County updated the plan and reported that as a direct result of its implementation, the County’s CO2 emissions reductions averaged 2.5 million tons per year.30 However, Miami-Dade County’s 27% population growth over the 13 years of the planning time frame resulted in an overall increase in emissions. Although the plan kept the emissions lower than they might have been otherwise, the County realized the challenge of reducing emissions in a fast-growing community. The County also cited the failure of the state and federal governments to take more aggressive action as part of the problem.

Also in 2006, the County created the Miami-Dade County Climate Change Advisory Task Force (CCATF), made up mostly of technical experts in the climate change field, to advise the mayor (the County is a municipal county) and the board of county commissioners. The task force produced annual reports and investigated new strategies for reducing emissions. Most importantly, the task force kept the County moving forward with climate action planning that would lead to the next evolution of progressive action on energy and environmental issues.

In 2009, ICLEI chose Miami-Dade County as one of only three communities to pilot test its new Sustainability Planning Toolkit. The County saw this as an opportunity to revisit the CO2 reduction plan, broaden its scope, and use it to coordinate a variety of ongoing and new activities across departments and the community. The result of this process was the GreenPrint: Our Design for a Sustainable Future (GreenPrint) plan, released in December 2010,31 which addressed climate change as well as a broader set of environmental and sustainability initiatives. GreenPrint contains 137 separate initiatives that will reduce and avoid 4.6 MMT of GHG emissions.

In 2010, Miami-Dade, Broward, Monroe, and Palm Beach Counties formed the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact to coordinate climate action—both mitigation and adaptation. The compact includes 35 municipalities that have signed onto the Mayors’ Climate Action Pledge in support of the compact as well as a variety of nonprofit partners.

The compact calls on the counties to work cooperatively to do the following:

- • develop annual legislative programs and jointly advocate for state and federal policies and funding

- • dedicate staff time and resources to create a Southeast Florida Regional Climate Action Plan, which outlines recommended mitigation and adaptation strategies to help the region pull in one direction and speak with one voice

- • meet annually at the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Leadership Summits to mark progress and identify emerging issues32

The compact’s signature achievements have been the development of a common set of regional sea-level-rise projections for use by members, the creation of a regional climate action plan, and the hosting of an annual summit. As a member of the compact, Miami-Dade County sought to link the local efforts identified in the GreenPrint to a broader, regional initiative: “Through the Compact, the County also contributed to the development of the Regional Climate Action Plan. This plan contains over 100 recommendations which focus on sustainable communities, transportation planning, water supply, management and infrastructure, natural systems, agriculture, energy and fuel, risk reduction and emergency management, and outreach and public policy. Compact members, both municipalities and counties, track the implementation of these recommendations and share best practices through work groups, publication of case studies, regular implementation workshops and accompanying guidance documents, which have focused on issues such as transportation, water supply planning, stormwater management, and Adaptation Action Areas.”33

Most recently, the County has prioritized accelerating action on sea-level rise by forming the Sea Level Rise Task Force. In 2013, the task force reviewed the science and existing policy and issued seven recommendations. The County then adopted resolutions to direct action on these recommendations. Most notable were the creation of adaptation action areas to focus resources and implementation and the creation of the Enhanced Capital Plan to integrate climate risks into capital improvements planning.

Lessons Learned

According to Miami-Dade County, one of the most important lessons learned was that an issue could be studied for years but that this should not delay addressing it. To get started, the County secured strong and vocal support from the mayor and board, created a sustainability director position, and staffed it with someone good at planning, organization, and task management. This was critical for the success of climate action planning in a complex urban county with so many regional assets.

Building peer relationships and community partnerships proved to be key for Miami-Dade County. The County reached out to numerous communities that had completed sustainability plans and CAPs to learn about their experiences and get advice. In particular, the County received great help from the City of New York, which has recently completed its PlaNYC sustainability and climate action plan. Furthermore, starting in 2010, the County formalized regional cooperation through the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact.

Many communities struggle with determining how to get people interested in and supportive of climate action planning. Although the impacts of climate change seem like they would constitute an important motivator, the County found that this tended to scare or put people off. Instead, the County focused on energy efficiency and quality of life benefits and found the public and officials much more receptive. Figuring out what is important to the community when starting the process is a key to success.

Finally, the County found the process to be very iterative. In other words, as staff moved through the process and tried things or learned new information, they sometimes had to back up and do things over. The County has continued to update and revise GreenPrint, track implementation of the 137 measures, and publicize a “sustainability scorecard.” It continues to seek new ways to build cooperative relations and act on climate change.

City of Copenhagen, Denmark: Racing toward Carbon Neutrality34

Although this book is focused on climate action planning in the United States, there is much to be learned from global cities. Over 9,000 cities around the world have made commitments to address climate change.35 Copenhagen is a global leader not only in climate action planning but in a number of specific areas of climate action, such as green energy, bicycle transportation, and coastal adaptation (see box 9.8).

In 2009, Copenhagen established a goal to be the world’s first carbon-neutral capital by 2025—the mayor considers this a realistic goal that will be achieved. The City developed and updated climate action plans in 2002, 2009, and 2012. It has also developed a climate adaption plan (2011) to build resilience, especially around the issues of rainfall-driven urban flooding and sea-level rise.

Copenhagen’s 2012 emissions were 1.9 million metric tons (MMT) of CO2 with a goal of 1.2 MMT by 2025 (about 1.8 MT per person). They will then achieve carbon neutrality by offsetting the remaining 1.2 MMT through exporting excess green energy. This is a common strategy for carbon neutrality; often it is very difficult to eliminate all GHG emissions, so some offset or carbon sequestration strategies must be used to close the remaining gap. Copenhagen has already demonstrated success by reducing emissions from 3.2 MMT in 1990 to 2.5 MMT in 2005 to 1.45 MMT in 2015. A significant part of Copenhagen’s success in reducing GHG emissions has been due to two factors: investment in and commitment to bicycling, walking, and transit and a district heating system.

Copenhagen’s role as a world leader in bicycle transportation is well documented, but its other success—in district heating—is less well known and can serve as a model for other dense cities in colder climates. District heating (rather than individual heating of residences and businesses) now serves 99% of the city population, making use of waste heat from power plants, industry, and wastewater treatment.36 These power plants have run on coal, but the City (in cooperation with a private utility) is working to convert them to sustainable biomass. The goal is 100% renewable energy for the district heating system by 2020.

In addition to energy from biomass, the City is collaborating with the utility and the federal government to support the expansion of wind turbines for generating electricity. This is expected to contribute the largest share of future emissions reduction—over 300,000 MT CO2e. Since much of this is out of the hands of the City, it raises issues of uncertainty.

As part of its climate action planning, the City examined the economic implications of implementation. It looked at impacts to the municipal budget, cost increases to private investments, cost savings, and jobs creation. The analysis showed a positive return on the investments, especially those that result in energy conservation and efficiency. The analysis also showed the potential for 28,000 to 35,000 new jobs. The lord mayor of Copenhagen, Frank Jensen, and the mayor of technical and environmental administration, Ayfer Baykal, write, “Copenhageners will have so much to gain from the implementation of the Climate Plan. With the Climate Plan, we invest in growth and quality of life: clean air, less noise and a green city will improve everyday life for Copenhageners. The investments will secure jobs here and now—and the new solutions will create the foundation for a strong, green sector.”37

Copenhagen’s goal of being carbon-neutral by 2025 is ambitious and has received much attention, but the City has also recognized that it is being impacted by climate change and must seek to build a resilient city as well as a carbon-neutral one. In 2011, the City adopted the Copenhagen Climate Adaptation Plan. The plan prioritizes four strategies:

- 1. Development of methods to discharge during heavy downpours

- 2. Establishment of green solutions to reduce the risk of flooding

- 3. Increased use of passive cooling of buildings

- 4. Protection against flooding from the sea

Notable among all these strategies is a commitment to using natural systems and approaches as much as possible.

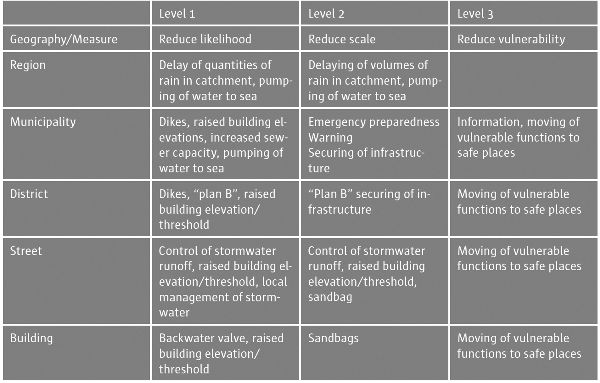

The Copenhagen Climate Adaptation Plan acknowledges three levels of adaptation based on the nature of the risk and city capabilities: “If the risk assessment shows that the risk is so high that it cannot be tolerated, the strategy of the City of Copenhagen is to choose actions that first of all prevent a climate-induced accident from happening [Level 1]. If this cannot be done—for either technical or economic reasons—actions that reduce the scale of the accident will be preferred [Level 2]. The lowest priority goes to measures that are only capable of making it easier and/or cheaper to clean up after the accident. [Level 3].”38 These three levels of adaptation are applied to different geographic scales to develop strategies for action. Figure 9.5 shows this approach applied to the issue of rainfall-driven flooding.

Figure 9-5 Copenhagen Climate Adaptation Plan. It shows three levels of risk management for flooding at different spatial scales.

Source: City of Copenhagen, Copenhagen Climate Adaptation Plan (Copenhagen: Author, 2011), https://international.kk.dk/artikel/climate-adaptation.

The City’s climate adaptation plan, like its climate action plan, identifies the co-benefits of action. The City establishes that adaptation strategies must not only address climate change but also improve the quality of life of the current and future residents. Specifically, it identifies more recreational opportunities, new jobs, and an improved local environment with more green elements.

Copenhagen’s climate planning is ambitious in scope and detailed in implementation. Climate planning is seen as supporting the broad goal of a more livable city and is integrated throughout city planning and operations. The City’s climate planning not only has produced the plans discussed but also has integrated the Municipal Master Plan 2011 “Green Growth and Quality of Life,” the Agenda 21 plan, the Action Plan for Green Mobility, the City of Copenhagen Resources and Waste Plan, Cycling Strategy 2025, and Eco-Metropolis 2015. If anyone has a chance of achieving carbon neutrality in the next decade, it is Copenhagen.

Lessons Learned

Copenhagen shows that an aggressive GHG emissions reduction target is achievable but that it requires significant investment and the willingness to transform transportation and energy systems in a relatively short time. This transformation is facilitated by a careful strategy of ensuring that these changes provide economic and social benefits, especially ones that have a positive economic return. The lord mayor of Copenhagen has been an effective champion in communicating the City’s vision.

In regards to climate adaptation, Copenhagen sees necessary infrastructure projects as an opportunity not just to make the city more resilient but to actually make it more livable. Projects to reduce street flooding also seek to improve the streets for biking and walking and to provide additional parks and open space in dense neighborhoods. As it states in its plan, “A greener Copenhagen is a climate-proof Copenhagen.”39