Maaleh Adumim – 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) east of Jerusalem, population approx. 40,000

Copyright 2012 - 2015 by Moshe Katz

All rights reserved.

Smashwords Edition

Israeli Krav Maga International

Maaleh Adumim, Israel

Designed by Sue Schoenfeld

Cover photo by Arie Katz

Chapter icons: © stringerphoto / Fotolia

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only and may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the work of this author.

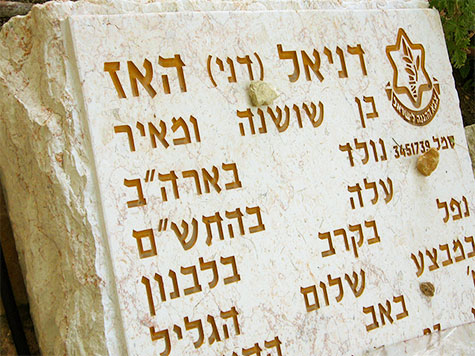

This book is dedicated to my nephew Arie Katz, a soldier of Israel, and his friends of the 101 paratroopers, who served in the Second Lebanon War.

To my brother Ethan Katz, a soldier of Israel, who served with an infantry combat unit, and battled terrorists.

To my dear father, Rabbi Paul M. Katz, of blessed memory, a soldier of Israel, who served in the Yom Kippur War and whose life was devoted to the people of Israel. His life and character will always inspire us.

And to my dear mother, Mrs. Hannah K. Katz, “A woman of valor who shall find” (Proverbs), whose love has been the cornerstone of my life.

Blessed be God, my rock, who teaches my hands to battle, my fingers for war.

—Psalms

The world does not pity the slaughtered. It only respects those who fight.

—Menachem Begin, The Revolt

Chapter 1 – A Warrior Nation Mindset

Chapter 2 – A True People’s Army

Chapter 3 – Secret Ingredient of Israeli Defense

Chapter 4 – Warriors from Childhood

Chapter 6 – A Gun Packing Nation

Chapter 9 – From Pain to Productivity, From Darkness to Light

Chapter 10 – Business Mentality

Chapter 12 – Warriors Make the Nation

Chapter 13 – Warfare in Biblical Times

Chapter 14 – Post-Biblical Fighting

Chapter 15 – Principles of Krav Maga/Israeli Self Defense

Chapter 16 – The United States, a Nation of Warriors, Again

Chapter 17 – The Gaza War (Protective Edge) and the Social Media Generation

Chapter 18 – How to Start Your Krav Maga Club

Appendix A – The Future, Continually Adapting

One day I was walking in my neighborhood. Walking through the hills of Maaleh Adumim in the Judean Desert of Israel I started humming, for no apparent reason, the tune to the “Jewish Partisans Song,” “Do not say this is my last walk…” (accessed June 30, 2015).

My thoughts turned to the forests of Poland and Belarus, 1941. I looked down at my feet and imagined for a moment the feet of the partisans, their mud covered boots trekking through the forests, never knowing if today would in fact be their last day, if this walk would be their last journey in this lifetime, or who among their friends will not be with them tomorrow. In a way I am continuing their walk; in a way I am living their dream.

My thoughts turned to all of them—the partisans, ghetto fighters, defenders of Masada and Jerusalem, cousin Willie at the Battle of the Bulge, Moses and Joshua, Phineas the Cohen, the Jewish Legion, soldiers in the wars of 1948, 56, 67, 70, 73, the Lebanon Wars, the Gaza Wars, counterterrorist units, Jabotinsky and Trumpeldor, King David and Samson.

My thoughts turned to all our people who over the course of our history slung a rifle over their shoulder, or a bow and arrow, or strapped a sword to their side, left their homes, and went off to fight for our freedom. It is because of them that today I can take a walk in my own land—the land where my forefathers walked. I will never take this for granted. This book is about these Jewish warriors.

Maaleh Adumim – 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) east of Jerusalem,

population approx. 40,000

I took a taxi in Long Island, New York, on my way to JFK Airport after teaching Krav Maga to a group of American soldiers. The driver, Hezi, was an Israeli. He had been living in the United States for twenty-five years. As he helped me with my luggage, he noticed that one of my bags—a green military bag I used while serving in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF)—had numbers on it. He identified the numbers as my military ID and knew the year I had served. It turned out we were the same age. We became good friends.

There was an immediate bond. No longer passenger and driver, we were united by a shared history—we both served; something unspoken took place. The bond goes back thousands of years to the ancient warriors of Israel who battled the Canaanites, the Greeks, and the Romans. This is Israel, a nation united by a dream and a long shared history. Guns, swords or spears, the Tavor rifle, or the slingshot of young David—a warrior nation. We have spent thousands of years fighting to be free.

This book is not about governments. It is not about political leaders. It is not about national policy or international relations. It is not about strategy or questions such as whether or not an attack or a war was justified.

It is about people—ordinary people, people who have been asked to do extraordinary things, and have done so.

The people of Israel have risen to the challenge, neither seeking a reward nor receiving one. Without questions, without hesitation, they left their happy lives and answered the call to arms. And when the fighting subsided, they tried to return to normal lives, with their scars and their traumas. But life in Israel is anything but normal, for this is a nation at war, at war for survival.

When the Jewish people, the people of Israel, began coming home to the Land of Israel, they did not have war on their minds. After being forcibly expelled and driven out of their homeland many centuries earlier, the “wandering Jews,” scattered around the world, kept dreaming of returning home, to the small strip of earth simply known as “The Land,” The Land of Israel. Individual Jews, small groups, sometimes entire communities, did manage to return to The Land, but not until the 1880s was a more massive return possible.

The Jews had dreams of utopia. They wanted to befriend the Arabs and adapt to the Middle East. Many early photos show Eastern European Jews dressed in Arab garb and riding on camels; they wanted to fit in; they wanted peace. Reality was quite different and the need for organized self-defense soon became apparent. Reluctantly, the utopian Jewish farmers became fighters. It was either fight or be killed.

The symbol of the IDF is a sword (a symbol of war), an olive branch (symbolizing the Israeli desire for peace), and the Star of David (symbolizing Jewish history). Every government of Israel, since its establishment in 1948, has reached out for peace, but prepared for war. The long sought-after peace has proven elusive, perhaps impossible. As the prophet Ezekiel said so many years ago, “Peace, peace but there is no peace” (Ezekiel 13).

I recall when I was a young child, people would see my dear mom with four young boys and they would say, “Four boys—four future soldiers.” This angered my mother who would say to herself, “Bite your tongue, by the time my boys are old enough to serve, there will be peace.” So every mother hopes. Today, many years later, her grandchildren are serving in the army, in combat units, and there is still no peace in sight.

Back in 1967, I was playing with my friend from next-door. His name was Edo, an Israeli born boy. I can picture the day like yesterday. I recall exactly where we stood in our beautiful backyard. We heard the sound of a plane and we both looked up to the sky. I looked up for just a moment, but Edo, he just kept staring. I tried to get his attention, but Edo’s eyes were glued to that plane. He watched it until it was totally gone from sight. “What was that all about?” I asked him.

Edo, only six years old, answered simply and to the point, words I still remember to this very day, words I shall never forget, “There was a time when everyone else had planes but we did not. Now we too have planes.”

The dispersion and exile and the return, the Holocaust and the rebirth of the State of Israel, the transformation from perceived helplessness to warriors; this is what he was saying. A six-year-old Israeli boy understood it all; summarizing thousands of years of history in just a few words. And I can still see that plane flying away…“There was a time when everyone else had planes but we did not…”

I was just a child when I was introduced to international terrorism. The year was 1970. My aunt, uncle, and infant cousin Tali came to visit us in Israel. As they boarded their TWA flight back home to New York none of us could imagine the ordeal about to unfold. A few hours later we heard the news—the plane had been hijacked by Arab terrorists and taken to Jordan, fate unknown.

My father, of blessed memory, was in the barbershop getting a haircut when the news was broadcast on Radio Israel. The shock jolted my dad out of his seat. The barber’s scissors nicked his ear.

My aunt and cousin would end up spending a week as hostages in Jordan, along with hundreds of other passengers. My uncle, along with some other select hostages, would spend six weeks in captivity. The ordeal would change their lives.

That day the terrorists attempted to hijack four planes as part of their struggle against the State of Israel. This was the beginning, the birth, of international terrorism, the curse that would come to plague Western society in years to come, a cancer we are still fighting today. The Western world had no training in this kind of warfare; no understanding of the terrorist mindset. The Israelis, however, were already veterans of this war.

Of the four attempted hijackings, three succeeded. The only one to fail was the attempted hijacking of EL AL Israel Airlines. Four terrorists tried to board the EL AL flight. Two of them aroused the suspicions of the security staff and were refused entry. The two remaining terrorists, infamous female terrorist Laila Chaled and Patrick Argüello, managed to board the EL AL flight. The rejected terrorists proceeded to book a Pan Am flight, boarded without any difficulty, and hijacked it.

On board the EL AL flight, things did not go as smoothly for the hijackers. The operation had been planned for a team of four. Argüello hesitated. Laila Chaled assured him she had done this before and all would go smoothly. She had hijacked before. This time it did not succeed.

The terrorists stood up and pulled out handguns and hand grenades and announced that the flight was being taken over by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). The general international policy in those days was to cooperate with the hijackers and enter into negotiations, not to resist and endanger the passengers. The crew and passengers of EL AL Israel Airlines thought differently. The terrorists had not counted on resistance and Israeli stubbornness.

The first thing to go wrong for the terrorists was the takeover of the cockpit. As planned, Laila Chaled stood outside the cockpit with a pistol held to a flight attendant’s head and a hand grenade in her other hand. She demanded the pilot open the door at once. But the pilot was no ordinary civilian. His name was Uri Bar Lev and he was a former captain in the Israeli air force. No terrorist was going to hijack his plane.

Captain Bar Lev refused to open the cockpit door. He would not be the first to blink. Instead, the former combat pilot sent the aircraft into a nosedive. The nosedive had the same effect on the passengers as an elevator going into free-fall. The sudden move knocked the hijackers off their feet, just as Bar Lev had planned.

Then the Israeli passengers went into action. As one passenger put it, “I made a decision that they were not going to hijack this plane. I decided to attack him rather than wait and see what happens. So I jumped him. I got shot in the shoulder.”

The terrorist, Argüello, was hit over the head with a bottle of whiskey and then killed in the struggle by his own gun. Laila Chaled was tied up with neckties and belts provided by passengers. The pilot summed up the fighting spirit that day, “I didn’t succeed because I was a better pilot. It was only because of my attitude that we were not going to be hijacked. Our mindset is to fight terror.”

Here is the key to Israeli self-defense—attitude! It is a resolve to fight terror, not to give in, not to be a victim anymore. This is a universal aspect of Israeli culture born out of the bitter experience of being an unwelcome guest in foreign lands and being surrounded by a hostile Arab population.

The pilot was trained to improvise, to think “on his feet,” or in this case, on his seat, in the air. He used what he had available, another key to Israeli self-defense, and came up with a brilliant way to fight back. Equally important, the pilot knew that once the terrorists were on the floor, the crew and passengers, all former soldiers, would respond as warriors; they would unite and fight back. He could count on it without even asking them; for they are part of a warrior nation, this is part of their upbringing, their military training, their lifestyle.

Shortly after 9/11, in November 2002, an Arab terrorist, twenty-three-year-old Tawfiq Fukra, tried to hijack an Israeli flight to Turkey. Somehow he managed to smuggle a knife on board the aircraft. He started swinging his knife at the flight attendant, threatening her. The flight attendant reacted instinctively with evasive techniques designed to buy time and prepare a better defense. She managed to avoid getting cut by using the techniques she learned as part of her basic military Krav Maga training. This gave the flight marshals time to react. They quickly neutralized the threat.

The key here, as in the 1970 incident, was that neither she nor anyone else panicked. They made use of what was at hand and relied not only on their own training, but on the preparedness of everyone around them. This is the Israeli mindset.

Nowhere is that mindset more in evidence than in Krav Maga, the native Israeli martial arts system. Krav Maga emphasizes simple, easy to remember gross motor moves, reliance on human instinct, natural body movements, and utilization of whatever one finds available.

Krav Maga knife defense

Be Alert!

Even before boarding a flight, Israelis are on alert. As they are in line checking in, they check out the passengers. If someone notices anything unusual or out of place they will notify the security staff. They never forget that they are part of the security staff. Krav Maga expert Itay Gil puts it this way, “You are accountable for your own life, and ultimately you are responsible for safeguarding it” (Itay Gil and Dan Baron, The Citizen’s Guide to Stopping Suicide Attackers, Paladin Press, Boulder, Colorado, 2004).

In 1956, after Egypt violated international law and nationalized the Suez Canal; Israel, Britain, and France took control of the canal in a military operation. After much pressure from the Americans, and assurances of safety, Israel withdrew from the canal. In 1967, when Egypt again violated all agreements and crossed into the Sinai Peninsula, Israel waited for the United States to act on its assurances. No help was forthcoming. Israel realized that one is accountable for his own survival. Written guarantees and promises from others are not to be relied upon. We are accountable for our own safety.

Look for Allies on Your Flight

If you are a trained fighter, if you have skills that can save others, you must assume added responsibility for the protection of others. As you find your seat, and as a fighter, you should only take an aisle seat so you can get out and fight if need be; look for allies. You do not have time to interview people as to their abilities and background, but keep an eye open for people who look like they can handle a fight. You will have to rely on your judgment.

Anticipate the Worst Case Scenario

If the worst does happen and you have to fight back—then fight you must. In Krav Maga, we stress that you should never make a bad trade. Sometimes in battle people get hurt or die. If the terrorist is threatening one person and demands to get into the cockpit—it is a mistake to give in, despite your desire to save that one person’s life. You might be trading one life for the safety of all the other passengers. And even that one life will not be saved if the plane goes down.

Instead, think like a warrior. Fight back. If one hostage gets killed, then that is a tragic consequence of saving one hundred lives. Don’t make a bad trade. This may be harsh thinking, too much to expect of an average citizen, but Israelis are not average citizens. Who are the Israelis? How did this group of people emerge?

The modern State of Israel (accessed June 30, 2015) is situated in the Middle East with the Mediterranean Sea on its western side. It borders with Lebanon to the north, Syrian to the northeast, Jordan on the east.

The population of Israel was estimated in 2014 to be 8.2 million people. It is the world's only Jewish-majority state; 6.2 million citizens, or 74.9% of Israelis, are designated as Jewish. The country's second largest group, Arab citizens of Israel (accessed June 30, 2015), number 1.7 million or 20.7% of the population (including the Druze and most East Jerusalem Arabs).

Israel in the Middle East © Ruslan Olinchuk / Fotolia

In 1967, as a result of the defensive Six-Day War, Israel liberated the biblical lands of Judea, Samaria, the Gaza Strip (accessed June 30, 2015), and the Golan Heights. Israel also took control of the Sinai Peninsula, but gave it to Egypt as part of the 1979 Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty.

Since Israel’s conquest of these territories, settlements (Jewish civilian communities) and military installations have been built within each of them. Israel has applied civilian law to the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem, incorporating them into its sovereign territory and granting their inhabitants permanent residency status and the choice to apply for citizenship. In contrast, Judea and Samaria have remained under the military government, and the Arabs in this area cannot become citizens. The Gaza Strip is independent of Israel with no Israeli military or civilian presence, but Israel continues to maintain control of its airspace and waters.

It is important to understand Israelis—who are they? Where do they come from? Some Israelis have direct roots that go back thousands of years, despite all the conquests of our land and the many foreign rulers, they clung to the land and never left. Others can trace their return to Israel to a few hundred years ago. The “newer” returnees came to Israel during the Zionist movement that began in the 1880s.

No matter when they returned—they worked the land, cleared the swamps, fought off the Arabs, and expelled the British troops. Others survived the Nazi war machine, fought in the ghettos and the forests, and then arrived in Israel and fought in several of Israel’s many defensive wars. They are not the warm and cuddly type. This is a fighting nation.

Israel is a nation comprised of citizen soldiers who are ready to serve at a moment’s notice. Israel is a nation that realizes that if we do not act, we will die; our history has taught us this. It is a nation that lives by the words of the ancient rabbis who said, “If am not for myself, who will be? And if not now, then when?” (Ethics of the Fathers 1:14).

As Israelis, we are taught,

• Do not trust the words of the enemy and hope for the best.

• Do not cooperate with their demands.

• Assume the worst and trust no one.

Prime Minister Golda Meir once remarked about her difficulties in dealing with American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, “He is a wonderful gentleman; the only problem is that he thinks of the rest of the world as equally wonderful gentlemen.”

A nation of warriors is defined as a people with a warrior’s mindset, which is very different from a citizen’s mindset. When tragedy strikes, an ordinary citizen responds by saying, “Thank God it wasn’t me!” or “Thank God I was not there!” A warrior, whether a police officer, martial artist, fireman or soldier, responds by saying, “I wish I had been there, I could have done something to help those people.”

One of my handgun instructors told me that whenever he hears about a terrorist attack he gets down and does as many push-ups as he can. It is his way of saying, “I must be strong. I must be prepared. Next time, perhaps, I will be there and I want to make a difference. I must be ready to act.” Being ready to act—a warrior knows there will most likely be no warning, no chance to get organized. Israeli culture stresses the belief in always being ready, in anticipating the next attack, in thinking ahead.

A warrior responds with action. In Israel, when there is the sound of an explosion or gunshots, people run toward the sound, not away. They are thinking, “I have military training, I have medical training, perhaps someone needs my help.” These people do not consider themselves heroes, just people doing what is right, what is expected of them.

CHAPTER 1

A Warrior Nation Mindset

Many Americans are obsessed with personal freedom. Personal freedom is so important to them that they are often unwilling to take the necessary measures to protect that freedom. If security measures go against their principles of freedom they would rather take the risks than compromise this sense of liberty.

As an example, having a security guard at an airport or store empty the contents of one’s bag or pockets offends most American’s sense of personal freedom. But that is one of the very measures necessary to protect the personal freedom of every American—including the freedom and security of the person being searched.

In Israel, we are not so sensitive. We have less privacy and we understand the need to compromise our personal freedom in the interest of greater security. As Uri Dromi of the Israel Democratic Institute said, speaking of the Jewish state, “The question of civil liberties is always in the shadow of security.” Israelis ask, “If you don’t exist, what’s the point of having civil rights?” he noted. “The first right is the right to live, and this is what Israelis get in the milk of their mothers. There is security and then, there’s democracy. People in America value democracy first” (Jerusalem Post, April 20, 2007).

With a warrior nation, fighting, dying, and sudden attacks, are all par for the course. Americans do not have this mindset, as evidenced by the April 16, 2007, massacre at Virginia Tech. On that horrific day, a mentally ill student, Seung-Hui Cho, killed thirty-two people and injured many others in what was the worst shooting incident in US history. In two separate shooting incidents, about two hours apart, Cho gunned down terrified students and staff in cold blood. The first victims were shot around 7:15 am; about two hours later Cho came back for more.

There was only one hero that day, an Israeli, Professor Librescu. He was seventy-six years old yet he did what none of the young people, of many nationalities, were able to do. When he understood that a murderer was on his way into the class, he kept the door shut with his body so his students could escape out the window. He died after being shot multiple times through the door.

William Daroff, director of the Washington office of the United Jewish Communities said, “The first thing that occurred to me about it, besides the tragedy of it, is how his heroism was informed by his experience as an Israeli. He clearly had thought about terrorism as an Israeli and, with a split second to respond after hearing a gunshot, went into autopilot, barricaded the door with his body and gave his students time to flee. Being an Israeli, having that mentality of how to deal with this sort of crisis comes more naturally.”

Autopilot; a typical Israeli is alert, like an animal in the jungle, always aware of potential predators. Most humans have lost this animal instinct, but Israelis know that wherever they are, they can be the target of a terrorist attack; we cannot afford to be lax. “The guardian of Israel does not rest and does not sleep” (Psalms 121:4) in the battlefield, at home, or on vacation. We are always on guard.

A warrior in battle should never be shocked by an enemy attack. When the attack comes, he should know how to respond. A civilian can be caught off guard. In Israel, the whole nation responds as the combat warrior. Dromi commented about the students’ response at Virginia Tech, “The big difference is that for them it looks like out of the blue. For us, it’s a sad way of life.” Israelis are experienced with war and terror. “Once they have this kind of basic preparedness in the back of their minds, if this happens, people don’t fall off their feet thinking that something unthinkable has happened, which is the feeling that people have here [in the United States] today” (Ibid.).

Israelis don’t wonder, “How could this happen? Why would anyone want to hurt us?” They know the world is a harsh place and bad things happen. They know they must learn how to cope and to protect themselves.

During the Virginia Tech massacre, the young American college students, raised with freedom and liberty, were not able to respond like warriors; they froze like a deer in the headlights. Yet the old Israeli, the Jewish holocaust survivor, had already tasted terror in his life and he knew how to respond. He died as a warrior.

Since the Civil War, America’s wars have all taken place overseas. Most Americans have never seen an enemy face to face or had to barricade their homes or worry about being attacked while shopping.

In Israel, it is different. The war is everywhere. It is at all our borders, it is overseas where Israeli tourists are targeted (Bulgaria, India, France, Argentina, Germany, Nairobi, United Kingdom, United States), and it is in our shopping malls, cafés, our buses, and on our streets. It is also in our homes and in our kindergartens. Every Israeli is a front line soldier; men, women, children and the elderly. Every home is a mini fortress.

If you were an Israeli, you might find yourself pushing an attacker off the bus or defending yourself against a knife wielding Arab in the Old City of Jerusalem. You might alert authorities and your fellow citizens to a suspicious object while out on your morning walk or to an Arab girl with a large package walking into a crowded supermarket. No one would think you were unusual. The alertness and training of the average citizen/soldier has prevented many potentially deadly attacks.

The lines between civilian and warrior are blurred at home as well as in public. After the wars in the 1960s and 1970s, a law was passed requiring that each new home built have a bomb shelter large enough to accommodate all members of the household. An apartment building must have a bomb shelter sufficient for all the residents.

Following the first Gulf War in 1990, the law was amended to require new construction to have a “sealed room,” one that could be hermetically sealed to protect against chemical weapons. Public education programs teach citizens how to prepare the room and how to use the atropine emergency kit. Every citizen has a personal gas mask. Sealed protective cribs were designed to protect babies. Special programs to train the home guard are part of all high school education, and home security is a required course of study.

To protect against less sophisticated terrorists, most people install metal bars over their home’s windows. Many people own handguns and are trained in their use. Houses are indeed mini fortresses. Schools are similarly equipped. Young children are drilled in how to behave during times of combat. In a sense, they are young soldiers in training.

When I drive home at night, I must drive through the barricade set up at the entrance to my town. Several soldiers will be there and I must drive through a short obstacle course while they eye me. They might stop me and ask me a few questions.

When I go to the supermarket or mall, I must stop my car while an armed security guard examines my vehicle, asks me a few questions, and opens the trunk. (I never leave anything in the trunk that might cause me embarrassment.) Before I enter the building, I will empty my pockets, open my bag, and walk through a metal detector with an armed guard at the ready. In day-to-day life, it is hard to forget that the enemy is all around, and that we must always be on high alert.

Airline Security

Israeli airline security is like no other. The last, and only time an EL AL flight was hijacked was in 1968. This was the first act of terrorism perpetrated against EL AL, Israel’s national airline. On July 23, 1968, terrorists, members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, boarded an EL AL flight leaving Rome, took over the plane, and landed it in Algiers. Since then no one has succeeded in hijacking an Israeli plane. I believe that EL AL is the safest airline in the world, and Israel’s Ben Gurion International Airport is the safest airport in the world. That is why I only fly EL AL.

What is EL AL’s Secret?

Part of it is attitude, resolve, stubborn refusal to be a victim, and military training; all working together to create a combat mindset. But there is more to it than that. Americans blindly look for weapons. They are reluctant to profile, believing that goes against an American sense of freedom and equality. We don’t have that luxury. We profile and we make no apologies for it.

Simply put, profiling is the best method for spotting, and stopping, terrorists. Even in this age of technology, human instincts and study of human behavior is the key to spotting potential terrorists. No machine can replace a human being. Profiling helps focus extra attention where it is most needed.

In Israel, unlike the United States, not every passenger has to take off his shoes and belt. We believe that if you use a “one size fits all” screening process, you lose your edge. You become machinelike, operating automatically. “Security is first and foremost based on common sense, which is supposed to provide you with the right intelligence, technology and modus operandi,” says Pini Shiff, who served for thirty years in the Ben Gurion Airport security division. “It is all about brains, since if you do everything automatic, it won’t work” (Jerusalem Post, January 1, 2010).

Another airline employee added, “Profiling makes the biggest difference. A man with the name of Umar (like the terrorist who attempted to set an American plane on fire in 2009) flying out of Tel Aviv, whether he is American or British, is going to get checked seven times.”

In the United States, on May 1, 2010, Faisal Shahzad, a Pakistani born terrorist tried to bomb Times Square in New York City, but failed. His name was placed on the “No-Fly List,” and yet on Tuesday, May 4, 2010, he was sitting in his seat on his way out of the country. At the last minute someone realized the mistake and ordered the plane back, just as it was about to take off. American authorities downplayed the incident and stressed that in the end he was caught, but they did not address the fact that he got through their security system and nearly flew away.

“Faisal Shahzad was aboard Emirates Flight 202. He reserved a ticket on the way to John F. Kennedy International Airport, paid cash on arrival and walked through security without being stopped. By the time Customs and Border Protection officials spotted Shahzad’s name on the passenger list and recognized him as the bombing suspect they were looking for, he was in his seat and the plane was preparing to leave the gate” (Associate Press Writers, May 4, 2010).

So, he has an Arab name, is traveling alone, bought his ticket with cash at the last minute, is probably quite nervous that someone will stop him at airport security, and no one even questions him. In Israel, we have learned that such people should be stopped for questioning. Israeli security personnel are trained to pick up the slightest twitch or body gesture that would indicate something is suspicious.

Lessons Learned: Athens, Zurich, Berlin, Brussels, Lod

Israel learned its lessons the hard way. Long before the rest of the world woke up to the threat of international terrorism, Israel was already a veteran at battling terrorists. Back in 1968, on December 26, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine struck again. Two of their members attacked an EL AL plane in Athens, killing an Israeli mechanic. Israel responded quickly by attacking the Beirut airport in Lebanon and destroying fourteen planes. In 1969 Arab terrorists attacked EL AL planes and offices in Zurich, Athens, West Berlin, and Brussels.

I recall back in 1972, I was living relatively close to the airport. It was May 31, 1972, to be exact, the day the name “Kozo Okamoto” became embedded in my memory. Three Japanese terrorists, working on behalf of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine surprised the guards at the Israeli airport. The three terrorists had been trained by the Arab terrorists in Lebanon. Arriving from Paris on Air France, the three conservatively dressed men carrying violin cases did not attract much attention. In the waiting area they opened their violin cases, took out automatic weapons, cut down in size to fit the small case, and opened fire indiscriminately on whoever happened to be there. As they changed magazines in their weapons, they threw hand grenades at the crowd. One of the terrorists, Yasuyuki Yasuda, ran out of ammunition, and was accidentally killed by his comrades (some say he was killed by Israeli counter-fire). A second terrorist, Tsuyoshi Okudaira, committed suicide. The third terrorist, Okamoto, was badly injured, but not before the three terrorists managed to kill twenty-six people, and injure eighty. Those murdered included sixteen Christian pilgrims from Puerto Rico. They had come to tour the Holy Land and pray; instead they experienced what we have to deal as part of our daily life. At the time no one expected Japanese terrorists, today we are wiser. Every guest can expect a close look.

So yes, we do profile. When my non-Jewish students from around the world come to Israel to train with me in Krav Maga, I warn them, “Do not be offended, you will be asked questions at the airport, tell them my name and why you are here. Give them my phone number; they can call me if they want to.” Understand that we have learned from bitter experience that we must be careful, even at the risk of offending an innocent tourist.

One of my students was connecting to an EL AL flight in Asia. He is a young, dark, athletic looking man, and was traveling alone. He was spotted in the crowd and pulled aside for extra interrogation. Being a young, happy-go-lucky fellow, he took it all in stride. “Why were you in this country (a certain Asian state)? What were you doing there?” the female officer asked him.

“I have friends there,” he responded honestly.

“How do you know these friends? What did you do with these friends?” Extensive questioning, all answered honestly, revealed no nervousness on his part and no contradictions in his answers. His honesty proven, and a thorough body check along with a special test to see if he had come in contact with explosives, cleared him for travel to Israel.

All the above took place outside the borders of Israel, in faraway Hong Kong. As I experienced in Frankfurt, Germany, as soon as you entered “EL AL territory,” you felt that you were already in Israel. For me, an Israeli citizen, it is a warm, comfortable feeling, like I am already halfway home. For a terrorist it must be a feeling that the long arm of Israeli security is about to catch him.

Students of mine arriving from the United States also felt they were entering some sort of new reality, a world different from their own. Being young, athletic looking, traveling alone, not Israeli and not Jewish, they naturally aroused some suspicion and warranted extra security measures. One student had his hand luggage taken away for more thorough searching. His music player, cell phone, and other electronic devices were thoroughly examined. His shoes were checked and tested for possible chemical contact. Both he and another student, on different occasions, were escorted from the time of check-in until the moment they boarded the plane. From the moment they checked in until they were on the plane they had an Israeli security guard constantly by their side. One even experienced a “changing of the guard” during the long wait to board. One asked to go to the rest room, his guard at the time was a female officer; she responded, “Wait until you are on the plane.” The guards watched my students and did not allow them any contact with anyone from the moment they entered “EL AL territory” until they were seated safely on the plane.

January 2011, I am sitting at Bank Leumi talking about my account when my cell phone rings. I glance at the number of the incoming call, it is a 271 country code; I have no idea where this is coming from. I have never received a phone call from such a number. I answer the call, it is an Israeli on the phone; his accent and perfect Hebrew are unmistakable. But where on earth is he calling from? He is calling from South Africa. He is EL AL security working the South African airport and he has detained a young man for questioning. Clearly the young suspect gave him my phone number, as I instructed him. “Do you know why I am calling you?”

I put two and two together and say, “Yes, you must have detained Alex, he is a student of mine, he is on his way to Israel to train with me. He is a good guy.”

“What does he look like, how old is he?” I answer with full details.

“Have you met him before, if so, under what circumstances?” Again, I am able to answer fully, without a hint of hesitation in my voice. “Where will he be staying?”

“In my neighborhood, Mitzpe Nevo, I rented him an apartment at the Cohen’s.”

“But that is a religious neighborhood?” (Wow, they are good! This is a small neighborhood in a small town, and yet they know the character of the neighborhood; very thorough training.)

“Yes, I know he is not Jewish, but we are very welcoming here.”

“You seem to have a bit of an accent, where were you born?”

“I was born in the United States, but moved here many years ago. I have lived in Israel most of my life.”

A few more questions and, “Thank you so much for cooperating, we shall let him continue.”

“Wow,” I thought, “now that is serious security!”

Although my student was innocent, there were certain things that caught the attention of our security officers. He had been to Israel just a short time ago; why was he back so soon? In fact, they remembered him from his previous trip. Not only that, but they remembered who he traveled with last time and under what circumstance. Why weren’t his previous travel companions with him? Why was he now traveling alone? There were legitimate answers to all these questions, but anything slightly out of the ordinary is noticed and warrants extra questioning. This is Israel, we take no chances.

I always tell my international Krav Maga guests, “As soon as you enter the EL AL terminal, you will already feel the Israeli atmosphere.” As the EL AL advertisement says, “EL AL; The most at home in the world. EL AL is Israel.”

Rome and Vienna, 1985

Thirteen years after the horrific “Lod Airport Massacre,” on December 27, 1985, terrorists simultaneously attacked EL AL ticket counters at the Rome and Vienna airports. In Rome, four terrorists walked up to the EL AL ticket counter and opened fire with assault rifles and grenades. The terrorists killed sixteen people and injured ninety-nine others before three of them were killed and the fourth was captured by the police.

Minutes later in Vienna, Austria, using assault rifles and grenades, three terrorists killed three people and injured thirty-nine others as they were standing in line at the EL AL counter. Years later, on July 4, 2002, I would land at LAX airport in Los Angeles just two hours after a similar attack at the EL AL counter. That attack resulted in the death of two Israelis. A lone terrorist, an Egyptian, opened fire at the EL AL counter, killing the two Israelis, one of whom lived in my brother’s community. The terrorist was shot and killed by Israeli security working for EL AL. All these events shocked us and shook our world. Years after the Holocaust in Europe it was clear to us that a Jew and an Israeli must still, always, be on guard.

When I visited Germany in 2010 to teach Krav Maga seminars, I paid close attention to the German airport security. The lines were long and the progress slow, unlike Israel where trained professionals know who to allow through and who to interrogate thus allowing a smooth and rapid check-in process. Again there was an obsession with checking hand luggage and not enough attention to the human element. Even though I was a foreigner, traveling on a foreign passport, not once did anyone ask me so much as a single question. Not once did I sense that anyone was actually looking at me. It seemed they actually made an effort to avoid eye contact.

The only exception was, of course, EL AL Israeli security. Upon reaching the EL AL counter I noticed Israeli security at work. The difference was quite obvious to me. I met a young German woman while waiting for the EL AL counter to open. The EL AL female officer, seeing us together, instructed us to go to a certain line. When I inquired in Hebrew why we were being sent to another line, the officer responded, “Oh, you are an Israeli, stay here on this line.” She said she thought we were together, perhaps a couple. Seeing that my friend looked typically German, we had been sent to a different line. Now, she questioned me separately while my new friend was sent for more thorough questioning.

“How long have you two been together? Did she pack your bags for you?” I explained that I had known Tamina for about twenty-three minutes; that we met while waiting for the EL AL counter to open, and that, no, she did not pack my bags, she never even saw my bags; I never saw her before. I was passed along quickly and given a certain plastic tag identifying me as a low-risk traveler.

Later, as we went through security, my friend Tamina and another new friend, Claudia, were asked to step into a small room for further questioning and more thorough checking. I went through like I was old buddies with the staff. Clearly everything about me indicated that I was an Israeli very happy to be on my way home. My new friends had to first do some explaining; Tamina said she had friends in Israel, perhaps the officer would ask—Who were they? How does she know them? Claudia would be passing through Israel on the way to another country, spending only a few hours at Ben Gurion airport. Perhaps they would ask—Why only a few hours in Israel? and so forth. In fact their bags were checked carefully, a few key questions were asked and they were allowed to pass. Once again security involved personal interaction, eye contact, studying body language while engaged in conversation, and giving special attention to those who might raise some questions. This is the Israeli way, and it works. So, yes, we do profile, and we stay alive.

Embarrassing Questions

In this day and age, I find that people are often willing to put themselves at risk of personal danger rather than take the chance of offending a total stranger. Clearly tact is important, and respect and courtesy should be valued, but one should not shy away from questions that could uncover important information. In Israel, we learn that one should not be shy or bashful.

In Hebrew, the words for bashful and dehydrate are similar and rhyme, so the saying goes, “He who is bashful will dehydrate.” The idea is also that one who is afraid to ask—will suffer the consequences. So we are not shy, we ask questions, even at the risk of offending someone. We are not as sensitive, or as “politically correct” as Americans.

Women are often embarrassed when asked, “Do you have an Arab boyfriend? Have you been spending time with Arabs while you were in Europe?” The questions are personal, embarrassing, intrusive and offensive, and not at all in keeping with today’s “politically correct” approach. So what? People’s lives are at stake. We know that terrorists will stop at nothing so we have little time for niceties.

On April 17, 1986, a pregnant Irish woman named Anne-Marie Murray made it past Heathrow airport security in London and was about to board an EL AL flight to Israel. Her bag had been checked by British airport security and passed inspection. During standard questioning by Israeli security officers, the Israeli officer became suspicious. “Her answers to our questions just didn’t add up,” recalled Pini Schiff (Jerusalem Post, January 1, 2010). She swore she was not given anything to carry on board. When the Israeli team inspected her bag they discovered seven kilos of explosives and a very sophisticated bomb. The detonator was hidden inside a calculator and was set to go off when the plane reached thirty-nine thousand feet. Murray had no idea the explosives were there. During the subsequent interrogation it was revealed that she had an Arab boyfriend, the father of her unborn child. He became her boyfriend only to gain her trust and use her as a human bomb, a martyr for Allah, without her even knowing. He was willing to blow up his “girlfriend” and their unborn baby. Her fiancé, Jordanian Nezar Hindawi, is now serving a forty-five-year sentence in England.

Israeli airport security has four levels. As you approach the entrance to the airport you will see two gates. They are manned by guards armed with M-16 rifles with their fingers on the trigger. These men are not only combat veterans, they are also trained security experts.

You will roll down your window for your first round of interrogation. “Boker Tov, Good Morning, where are you coming from?” They will listen to your voice and observe your facial expressions; they will look at your passengers. Any questionable behavior, any hesitation in your response, will warrant a further and more detailed inspection. The idea is to prevent a car carrying explosives or terrorists from entering the airport area.

The second level of security involves profiling the passengers. As you enter the airport terminal there will be some friendly uniformed individual, something like a server outside a nice restaurant. He will observe you as you walk in and might stop and ask you a question or two. He might ask to see your passport. He will write it down in his log book. Again, he is profiling and looking for clues.

Part two of the second level is more direct. Once you enter the line leading to your particular airline you will go through more formal questioning. The young security personnel will ask to see your passport and ask a few simple questions.

For most of us the questions, “Who packed your bags?”, “Were your bags with you the entire time?”, or “Did anyone give you a package to carry?” seem almost silly. We might ask ourselves, “Would a terrorist admit that someone gave him a package to carry on board the aircraft?” But the questions only seem silly because we do not understand their real intention. The young Israelis asking these questions are looking for clues, for body language, for specific indicators as to who will require further questioning. The body does not lie. They know what they are doing. Just as with Anne Murray in England, certain answers will indicate that more extensive questioning is required, and the Israelis always get their man, or woman.

“People think that profiling is old fashioned and invasive, but it saves the day. The Nigerian terrorist [Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who tried to blow up a Northwest Airlines plane over Detroit, December 2009] would have undergone comprehensive inspections at Ben Gurion airport, and without a doubt I can tell you the explosives he was carrying would have been discovered,” says Pini Schiff of the airport security division at Ben Gurion Airport (Ibid.). In the United States, it was clearly considered problematic to profile a young African. The result of this misguided policy, this liberal attitude, put all the passengers at risk.

We do not look for weapons first. We look for terror suspects, suspicious behavior, and anything out of the ordinary. It is like the difference between a loan officer at the bank who only looks at your financial record as compared to one who looks at you as a person and determines whether you as an individual are a good loan candidate. The Israeli security expert studies human behavior and looks for clues. The expert is constantly asking himself, “Could this person be a possible terrorist? Is it possible that a terrorist is using him?”

As a frequent traveler, and being in the personal security business myself, I have picked up some knowledge of what the experts are looking for. As one officer only half-jokingly said to me, “Don’t reveal our secrets!” So I shall not, but I will say this: everything about a person reveals something about that person and his intentions. You can learn a great deal about a person by observing his appearance and his behavior. Anything, anything at all, that reveals potential danger, will be picked up by the Israeli experts and dealt with before the suspect has any clue that they are on to him. In Israel you are protected; someone is looking after you.

Arabs are singled out for extra stringent security, even respectable doctors and lawyers. “Even if he is a perfectly respectable lawyer or businessman, he doesn’t know about the Arab taxi driver who handled his bags, and even if he thinks everyone who saw him off is all right, maybe his brother-in-law isn’t as all right as he thinks” (Jerusalem Post, March 23, 2007).

Do we profile? Of course! And we don’t apologize for it. Our friends will understand while our enemies will be frustrated. A former airport security examiner was quoted in the Jerusalem Post saying that the ethnic profiling system, with all the purely personal profiling it entails, is legitimate and necessary because it accurately reflects the demographics of anti-Israel terror. It is an undeniable fact that a hijacker or bomber of an Israeli or Israel bound flight is extremely likely to be an Arab or Muslim, while the chance of his being a Jew is infinitesimal (Ibid.).

Part three of the second level is the level you do not see, but it is there, and deadly. Throughout the airport, inside, outside, and all around, are plain clothed security. You will never guess who they are. They will appear as passengers just like you. But they are watching you, observing you, and should something look out of the ordinary they will arrange for you to be taken away rather swiftly. No one will even notice this. In the unlikely event of an actual attack; they will spring into action with deadly accuracy and eliminate the problem. Their training is based on past incidents, such as the Japanese terrorist attack in the old Lod airport, and an assessment of any possible scenarios that might potentially unfold.

The third level of security is the machines: CT scanners; metal detectors, and explosives detectors add an additional element, but they cannot replace human intelligence. We do not rely on machines. We rely on human judgment and human judgment involves profiling. The former airport security examiner said they were not terribly concerned about accidentally offending people and, “What was important was that the planes left on time and didn’t get blown up.”

Arabs and Muslims complain about being profiled, but Christian friends of Israel are more understanding. David Parsons of Jerusalem’s Christian embassy, and a resident of Israel for a decade says, “I don’t blame my government, I blame the terrorists.” He and his pilgrims appreciate that they are flying in safety. More and more, as international terrorism spreads, our Christian friends appreciate our attitude toward terrorism.

The fourth level of security is on the plane itself. Armed Israeli agents are seated among the passengers, blending in. They have received special training to thwart hijacking and bombing attempts in mid-flight. Over the years Israel has developed advanced training for these agents using mock planes where agents practice with live fire in realistic scenario training (Jerusalem Post, January 5, 2010).

Israeli airport security did not simply materialize out of nowhere. It was born out of necessity. El Al is considered by many to be the world’s most secure airline, after its security protocols have foiled a number of attempted hijackings and terror attacks. The Israeli method has proven itself in the most important category—the protection of human life.

Airport security reflects the fundamentals of our military training as well. In the Israeli army each member of a unit is trained to be a leader. If a commander can no longer function, there is always another who can assume command. It is a nation of leaders, not followers. As Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir said to American President Richard Nixon, “It is true that you are president of two hundred million citizens but I am prime minister of four million prime ministers.”

Soldiers are taught to improvise, to make do with whatever is available, to adapt to their surroundings and survive. This translates into everyday life where no one is willing to be taken advantage of and no one will take “no” for an answer. Israelis typically try to figure a way out, a way to outsmart the system. That is how they are trained. You can drop Israelis anyplace and they will find a way to survive and thrive, on their own.

That is what happened in 1976, when an Air France flight, with many Israelis on board, was hijacked to faraway Uganda. Israel had no contacts and no friends in Uganda. Another nation might have given up hope. Not Israel. They found a way to not only land a full commando unit, but passenger planes as well. They came home with nearly all the hijacked passengers. Tragically, one soldier was killed; Yonatan Netanyahu, brother of future Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

The Bible calls the nation of Israel a stiff-necked people, obstinate to the point of craziness. It can be frustrating and annoying at times, but it serves a purpose. That stubbornness has kept us alive as a people for close to two thousand years while exiled from our land without government or territory, discriminated against everywhere. We refuse to give up, we refuse to trust our enemy, we would rather resist. We have learned that there are few that we can trust, as the rabbis say, “respect him and suspect him.” We have learned to take action rather than wait and see what fate has in store for us.

Israelis are known for their survival skills. Both on a physical and emotional level Israelis seem to have above average survival skills, almost as if it was a genetic adaptation. Whether caught in enemy crossfire, or stranded in a foreign country without documents or money, or facing economic collapse, Israelis seem to have a remarkable ability to remain calm, survive, and come out on top, often thriving. In a classic joke, an Israeli man is captured by wild African tribesman and taken away deep into the jungle. When the rescue team finally arrives, they find him running a successful business staffed by locals who have now learned to speak Hebrew.

Israeli search and rescue teams are known as among the best, if not the best, in the world. These teams are sent all over the world to assist in rescue efforts. What accounts for this incredible ability to survive? And how can we learn from it?

Part of the answer can be found in a deep-seated appreciation of human life. This core belief stems from biblical values, is codified in Jewish Rabbinic law, and is embodied in the spirit of the Israeli nation and in the values of the IDF. Unlike other ancient cultures, capital punishment was almost unheard of among the Hebrews. Most such laws “on the books” were meant only as warnings for the purpose of intimidation and deterrence. Everything was done to preserve human life. Nearly all divinely ordained biblical laws were permitted, in fact commanded, to be violated, in cases where necessary to preserve human life. If consuming forbidden products, such as pork, were the only way to survive, then one was commanded to do so rather than forfeit one’s life.

A passenger who survived a six-week ordeal as a prisoner of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine when his TWA flight was taken hostage, faced this very situation. After several days he was at the point of starvation and he faced this choice. It was either eat or die, as he wrote, “For the first and only time in my entire life I eat this forbidden food.”

Human life transcends nearly all. If a Jew is held hostage and ransom is demanded, our rabbis permit us to sell holy objects, even a Torah scroll or a synagogue, in order to redeem the prisoner. The Rambam, Rabbi Moshe son of Maimon, writes, “There is no greater commandment than that of redeeming the prisoners…as they stand in danger of their lives, and one who turns his eye away transgresses the biblical command of ‘Do not stand idly by when your fellow man is in danger’ (Leviticus 19:16), and ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’ (Leviticus 19:18), and ‘You have no greater commandment than that of redeeming prisoners’” (Rambam, Laws of Gifts to the Poor 8:10).

Today, we see the same value for human life as Israel routinely exchanges one thousand Arab terrorists for a single Israeli soldier. The value of human life permeates our existence, as individuals and as a nation.

Israel is very reluctant to go to war. War means death. Most militaries have a concept of “acceptable losses,” a number of soldiers one can afford to lose to achieve a certain military or political objective. In Israel, even one life is a tragic and unacceptable loss. As the Talmud says, “One who saves one life of Israel it is as if he saved an entire world.”

Thus, it took eight years of constant bombardment of towns in southern Israel until Israel finally retaliated and attacked the Hamas terrorists in Gaza. In that conflict, as in all IDF operations, every effort was made to preserve not only the lives of Israeli soldiers, but also the lives of our enemies. As in all conflicts, Israel dropped leaflets in Arabic, warning the civilian population to evacuate before Israel attacked. This humanitarian measure, of course, takes away the essential element of a surprise attack.

Unlike Israel, our enemies do not value human life; they use the civilian population, families, women and children, as human weapons and shields. Their “fighters” hide among the civilian population and in times of trouble shed their military garb and mingle with the general population, putting everyone at risk.

With Israel’s advanced modern weapons technology, the IDF was able to pinpoint the homes and families at risk. Israeli soldiers contacted each family and warned them in Arabic of the impending Israeli strike. This move reduces the effectiveness of the strike, taking away the element of surprise, but, it is done out of Jewish respect for human life.

My brother, Ethan, fought against a terrorist stronghold in Israel. From the IDF position, safely outside the Arab town, using advanced electronic maps, they were able to pinpoint the homes where key terrorists were hiding. The safest and easiest approach would have been to simply bomb those apartment buildings from a distance. No risk, no fuss, no mess. However that would cause the death of Arab civilians, noncombatants, the “human shields” of the terrorists. The IDF chose instead to go in on foot and fight house to house. Eleven reserve soldiers, men with families, were killed that day.

In another incident, the IDF had accidentally hit a water pipe, leaving the noncombatant population without running water. Israel sent in repairmen, under enemy fire, to fix the pipe. This deep seated appreciation of human life translates into an appreciation of one’s own life. This produces a fierce desire to survive, to preserve one’s own life.

International law experts said that the IDF went to “great and noble lengths” to avoid civilian casualties while fighting Hamas terrorists in Gaza in 2014, but warned the IDF is taking “many more precautions than are required.” As a result, they feared that the IDF “is setting an unreasonable precedent for other democratic countries of the world who may also be fighting in asymmetric wars against brutal non-state actors who abuse these laws” (Ari Yashar, IsraelNationalNews, June 9, 2015, accessed June 10, 2015).

Long Term Survival

The Jewish people are survivors. The Jews have a long history of oppression, persecution, and…survival. During the Passover seder each year, we say, “In every single generation there arises an enemy who wishes to destroy us, but the Holy One, blessed be He, saves us from their hands” (Passover Haggadah).

“The People That Won’t Die”

We are the people that won’t die.

We’ve got a vision in our eyes and a mission in our souls,

to return to the days of old,

to our home in Israel.

Two thousand years I wandered, without a place to call my own.

As much as I tried, I could not call it home.

I fought for every nation and I died for every land,

but in my hour of need no one lent a helping hand.

We were burnt, we were gassed, we were shot at Babi Yar

Numbers on our forearms, covered with scars

and yet we continue to hold our heads up high,

eyes wide open, facing the clear blue sky.

The Jewish people are survivors. The Jews have a long history of oppression, persecution, and…survival. During the Passover seder each year, we say, “In every single generation there arises an enemy who wishes to destroy us, but the Holy One, blessed be He, saves us from their hands” (Ibid.).

Wandering the world for two thousand years, the Jew has learned to make lemonade out of lemons. At times he has sold his lemonade and made a profit, and has been criticized for doing so. He was denied citizenship, barred from owning land, kept out of professional guilds, denied entry to schools and colleges, deprived of natural rights and privileges, and all too often expelled from lands he called home. And still the Jew adapted and survived.

Without a home or an army, without a government to stand up for his rights, without a church or a pope to plead his case, the Jew survived. The culmination of being hosted in other nations’ lands was the Holocaust, the systematic murder of a people: genocide. With this the Jewish people faced the worst nightmare of human history.

And when it was all over, these dry bones, these tattered refugees and survivors, came home to Israel to be greeted by millions of Arabs who sought to finish what the Nazis had begun. Facing a harsh enemy and a harsh, neglected land, these survivors drained the swamps, fought off countless Arab invasions, and made the desert bloom. They created one of the greatest fighting forces on earth, and one of the world’s most advanced hi-tech industries. These are the people who make up the nation of Israel. These people know how to survive.

Modern Day Application

There is an old saying, “Tough times never last; tough people do.” It is true in life and it is true in combat and in a fight. The attack will eventually tire out; you simply have to outlast it passively, yet actively wait for your moment. For nearly two thousand years the Jewish people waited for their moment to return to Israel. While it may have been passive, it was also active. Hope was actively kept alive through prayer and study; small opportunities were seized and acted upon. Small groups did reach Israel, strengthening old communities.

The same idea applies to fighting. While fighting, I have often found myself in a bad position; an opponent pinning me down or choking me. Most times I did not have the ability to just throw off my opponent. I responded passively/actively. Holding on for dear life, I prevented the choke or arm bar from being applied, thwarting my opponent’s efforts and conserving my energy. I bided my time. When my opponent began to tire and his hold on me weakened—I made my move and countered successfully.

The same applies in daily life. We are not always in a position to “counter” our life circumstances, but we can respond passively/actively by doing all we can, hanging tough, knowing that if we just hold on long enough, our moment will come. The rabbis say that in the end of days two angels will be holding a rope, and all of mankind will be holding on to this rope for dear life, for if one lets go he is doomed. “I am telling you this,” the rabbi said, “so that you should remember to hold on tight, don’t let go.”

Minimizing Rather than Overreacting

When I began my Krav Maga training in Israel certain things became clear. There was a lot of full contact fighting, but there was no real dressing room, and for drinking water you had to go to the rest room. Clearly this was a no frills operation.

We were located right next to a hospital. Students joked that this location was chosen to accommodate the many students requiring medical care after getting hit. Our instructor himself was a combat medic and usually handled the injuries on his own, only rarely sending a student to the hospital.

When a student would get hurt, the instructor would look at the wound and say, “Lo kara shum davar” (nothing happened, this is no big deal). I figured, well this must be a minor injury. But then I saw some injuries that were clearly more serious and he still said, “Nothing happened, take it easy, it is a minor injury.” Much later I figured out what was going on.

It was only when I observed a group of students from abroad, and saw their reaction, that I understood what he was doing. Our teacher, Itay, is a warrior, he has spent his entire life being a warrior. He has served as a combat medic and he knows that the worst possible response is overreaction. If you overreact you cause panic, you make the situation much worse than it is. What a warrior does is minimize the situation. Do not tell an injured man, “Oh my God! This looks terrible!” That alone can kill him. What you need to say is, “Nothing happened, no big deal, you will be fine.” This will calm him and help the healing process. A warrior knows that he, and those around him, must remain calm. To overreact is to plant the seeds of disaster. You must always minimize any misfortune, get back on your feet and continue.

In fact, in the Bible it says that even in a most critical war, where all are required by law to serve, the cowardly are sent home, as to not cause their brothers’ hearts to melt during combat. “Any man who is fearful and fainthearted let him go and return to his house, lest his brethren’s heart melt like his heart” (Deuteronomy 20:8).

Attitude

There is a popular Hebrew expression: yihiyh b’seder—it will be OK. But yihiyeh b’seder is more than just “it will be OK,” it is an attitude. It is a feeling that nothing will hold us back, no matter how bad things are, no matter how bleak, yihiyeh b’seder, it will be all right, you will see. Sitting on the Suez Canal, being bombarded by the Egyptians, but…yihiyeh b’seder, it will be OK, you will see.

And, yihiyh b’seder is related directly to avarnu at Paroh, naavor gam et zeh—we got through, (survived, outlasted) Pharaoh of Egypt, we will get through this as well. Soldiers sitting in Suez, Egypt, another cup of Turkish coffee, we got through pharaoh once before, we will get through this. It will be OK.

We had the Holocaust, the Spanish/Portuguese/Mexican…Inquisitions, the persecutions of ancient Egypt, the wars of 48, 56, 67, 70, 73, 82, 06, 14. No matter what happens, we survive.

This attitude permeates Israeli society, civilian and military. This attitude is not a simple matter, not just an easy going way of looking at things; it is an attitude of hope, of change. A man’s physical body may be shattered, but his soul is intact. Israel may be bleeding, but its spirit strong. This is not the broken Jew of the exile, this is not a Jew who only grieves and hopes. This is the Jew of Israel, the Jew of hope, the Jew of redemption. No matter how bad things may appear we are, in fact, living in the best of times. We have witnessed the miracles return to Zion; we have witnessed the great victories and the revival of the Jewish people. We can cope with anything.

CHAPTER 2

A True People’s Army

We are a warrior nation out of necessity. We are a small nation and very simply we need everyone, no one is dispensable. This concept goes way back to our earliest days. Long before the modern State of Israel came into being, the ancient people of Israel had already formulated, under God’s direction, this warrior nation concept.

The idea was actually born in the Bible, the Torah, in the book of Bamidbar (“In the Desert” or “Numbers”). “From the age of twenty and upwards, all that are able to go forth in war in Israel, you [Moshe] and Aharon shall number them according to their units” (Bamidbar 1:3). Here it is made clear that this is a national obligation, every man who is able to fight must be ready to do so.

Later, in Bamidbar 32, we read how the members of certain tribes were reluctant to serve, they did not want to cross over into Israel and fight, they wanted to stay where the land was good. “Now the children of Re’uven and the children of Gad had a very great multitude of cattle, and when they saw the land of Ya’azer and the land of Gilad, that, behold, the place was a place for cattle, the children of Gad and the children of Re’uven came and spoke to Moshe, and to Elazar the Cohen (Priest) and the presidents of the community, saying, ‘thy servants have cattle…let this land be given to us for our cattle.’” They did not want to cross over the Jordan River, they wanted to stay put and not participate in the battles against the inhabitants of the land of Cana’an.

Moshe’s answer is relevant even today, “And Moshe said…Shall your brethren go to war, and you shall sit here?” This answer echoes through the generations, “Shall your brethren go forth to battle and you shall sit here!!” We can still hear Moshe, Moses, today; this is a national effort and no one is exempt. Your personal philosophy is of no interest to us, all must serve; all have a responsibility to protect the nation.

Moshe further explains that the act of sitting out the war has a disheartening effect upon the warriors. Not only are you not serving, but you are causing harm to those who do. “And why do you dishearten the children of Yisrael from going over into the land which God has given them?”

Moshe refers to the unfaithful spies who told the people of Israel that the land was too heavily defended and would be impossible to conquer. He compares the current draft dodgers to those spies and refers to them as “a brood of sinful men” who “augmented the fierce anger of God.” Upon hearing these powerful words from the great leader, the men of Re’uven and Gad change their attitude. The women and children and cattle will stay behind in the fertile land, but the men will go and fight alongside their brethren. “But we ourselves will go ready armed before the children of Yisrael until we have brought them to their place.…We will not return to our houses until the children of Yisrael have inherited every man his inheritance.”

“And Moshe said to them, ‘If you will do this thing, if you will go armed before God to war, and will go all of you armed over the Jordan before God, until He has driven out His enemies before Him, and the land be subdued before God, then afterwards you shall return and be guiltless before God, and the land shall be your possession before God. But if you will not do so, behold, you have transgressed against God.’” The answer of the men of Re’uven and Gad was crystal clear. “We will pass over armed into the land of Cana’an.”

A Nation of Warriors – Another Definition

As our ground forces entered Gaza during the war with Hamas, the idea of a “nation of warriors” once again emerged, reflected in the emotion-filled voice of the Minister of Defense and in the look of concern on the faces of the citizens of Israel. For us, deploying the military is not just a matter of “sending in the troops.” The word troops sounds too impersonal, the word troops has no personality.

What we are really sending in are our children, nephews, neighbors, friends, husbands, colleagues, and students. For us it is not “the troops,” it is Moshe, and David, Abraham and Jonathan; it is real people with names and personalities. We know their faces, their smiles, and their laughter.

There is not a home that is unaffected. If it is not your child that is sent in, then it is “all my friends’ kids.” It is the son of the guy at the desk next to you at work. It is the older brother of the boy whose bar mitzvah you just attended. It is the young man whose wedding is scheduled for next month. It is very close and personal.

Every single life is an entire world to us. Every single life is precious. As such, decisions to go to war are not taken lightly. We are not trigger happy. And still, we are a nation of warriors; us, our fathers and our mothers, our sons and our daughters. We do not have “acceptable losses,” each loss is a major tragedy. We cry over each and every soldier, we pray for each and every soldier. Each one is an entire world to us. We want to know as much as we can about each one, each one is an individual, a precious gift.

A Japanese friend commented on how I always say “our army” even though I am no longer in the army. The comment surprised me. She explained that Japanese people do not identify as such with the army; it is not “their” army. For us, yes, it is very much “our” army. We speak in terms of we are going in, or, we are pulling out, we suffered no losses.

One of the most beautiful phrases, music to our ears, is when we hear on the radio, “Kol kohotainu hazru be’shalom.” (All our forces have come home safely, in peace). I nearly get tears in my eyes just thinking these words. When we hear those words, all our emotions come out, and we say…Thank God!!! Thank God everyone is home safe, today no mothers will cry, today no wives will mourn, today no children will become orphans, today no fathers will recite the prayer for the dead, Today we have peace…if only for a day.

A recent first time visitor from Eastern Europe commented to me how surprised he was to be constantly surrounded by guns and soldiers; in the streets of Jerusalem, on the bus, in restaurants, everywhere. He was not prepared for it, but this is our reality.

The Israeli army has been a people’s army from the very beginning. There was no draft, just a bunch of people who said, “If no one fought, everyone would die” (Jerusalem Post, May 2, 2008).

One retired professor who fought in 1948 recently said that despite his preference for books, he chose to fight, “It was natural, it was necessary” (Ibid.). Two generations later, that professor’s grandson is about to be drafted. Now as then, he points out, “There is no questioning military obligations.”

The IDF is composed of three groups: a small number of professional career soldiers and officers, young men and women serving their compulsory military service, and the reserves. The uniqueness of a people’s army is expressed and manifested in Israeli society in three ways.

1. Compulsory Military Service

Every man or woman who turns eighteen years old receives a draft notice, and by law, must report to the draft board. Beginning in 2015, men will serve for thirty-two months, women for twenty four months. At the conclusion of their service some will be offered jobs in the standing army, known as Tzva Keva. The rest will be discharged and will be part of the reserves.

2. Obligatory Reserve Duty

Israel is a small country, always in great danger. Our economy cannot afford to sustain a large standing army even though it needs one. The unique solution is the reserve system where nearly the entire nation takes part in its defense, a true people’s army as envisioned by the American founding fathers in the 1770s. At the time, Americans feared a large standing army. They were concerned that it would lead to centralized power and tyranny. They had fought the British to escape just such a system. They wanted the power to remain with the people, and, in times of need, the people would defend democracy and freedom.

There were problems with the people’s army from the beginning. Although at the time many Americans owned guns and knew how to use them, serving as part of an army was a whole different ball game. General Washington was constantly frustrated by the different mentalities—the New Englanders were very different from the Virginians, the mountain people were different from the city folk. He had a rough time disciplining them to work as a single force. It is an indication of his brilliance, and fervent patriotism, that he succeeded. When the war ended the men went home, back to their farms. There was no reserve system and no follow-up training.

In the period following the Revolutionary War of Independence there was a great debate in America—some favored maintaining a large standing army to protect the newfound freedom while others feared it would become an instrument of tyranny. For the first hundred years or so of American history, the peacetime army remained very small—just big enough to fight the Indians and enforce laws.

In times of war, men were drafted and trained. However once the conflict was over, a familiar pattern developed—the great army that had saved the nation was rapidly demobilized. The people were tired of war and the soldiers went home, leaving only a skeleton force.