IDF soldiers in Lebanon enjoy a snack

One of those organizations is called A Package from Home. It began back in 2001 with a grandmother’s personal reaction to the second Intifada (Arab terrorist uprising). Barbara Silverman, Chicago native, long-term resident of Jerusalem, was “aghast at the intensity of the Arab campaign against Israelis.” Her reaction? Bake cookies. As a grandmother, she explained, she had few options. She was not going to start training with an M-16 rifle, but she sure knew how to bake cookies. Together with some of her friends, many of them with sons or grandsons in the army, she began to bake. Soon the packages grew to include many important items such as fleece jackets, fleece blankets, ski hats, extra underwear and toiletries in addition to the cookies and chocolates. Help came from the Association of Americans and Canadians in Israel (AACI), as well as donations from the United States. More volunteers came to help pack and the word spread. Vendors provided products at just above cost. They too had been soldiers and wanted to help in any way they could.

The project is still going strong. During the Second Lebanon War, A Package from Home sent twenty-two thousand packages to the front in thirty-three days. In the first week of the war in Gaza they sent over three thousand packages. Today, the organization focuses on “lone soldiers” as well as soldiers in the hospital.

Packages also come directly from the United States. In an amazing story, my brother, Ethan, who lives in New Jersey (and is a former combat soldier in the IDF), had a neighbor who told him he had just contributed money to have a package sent to the boys on the Lebanon front. Later, my nephew, Arie, serving in Lebanon with the paratroopers said he had, in fact, received a package with a note that it was contributed by that very family in New Jersey. Small world and one filled with much caring.

IDF soldiers in Lebanon enjoy a snack

Israel is built on the spirit of volunteerism. From its earliest days, volunteers, both local and foreign, have played a crucial role in the formation of the spirit and landscape of this society.

One such volunteer program is called Livnot U’Lehibanot “To Build and To Be Built.” Young American volunteers, led by Israeli guides, come to explore their heritage through volunteering, hiking, and seminars. The major focus of this program is community service. Activities range from cutting vegetables at soup kitchens to rebuilding dilapidated homes for the needy who cannot afford the repairs.

My niece, Mindy Katz, chose to volunteer in the Livnot U’Lehibanot program. She led a group of young American volunteers who came to spend three weeks exploring Israel. They were on a daylong hike in the North when the Second Lebanon War broke out. When they returned to their base, in the holy city of Safed, parents from the United States called frantically, urging their children to come home to safety. With only one exception, the entire group of volunteers stayed in Israel, to serve, and to share the fate of the people of Israel.

When the group awoke the next morning, they could see that the beautiful forests of Mount Meron, the mountain right across from Safed, were ablaze. These forests were planted by an earlier generation of volunteers who came to this barren, neglected land and made it bloom. The group was able to see the Katyusha rockets, fired by Hizbullah terrorists, landing nearby.

Mindy and the other group leaders gathered the volunteers and spirited them off to the town of Tiberius. In this town, centuries earlier, Jewish scholars set down the codes and cantillations of the Torah, preserving the ancient traditions for future generations. With the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, Tiberius evolved into a major Jewish center. By the 3rd century, Tiberius boasted many synagogues and houses of study. When Tiberius came under Hizbullah fire, the group made its way south to the safety of Jerusalem, too far for the rockets of the terrorists.

For the rest of their three week program they set out to do what they could for the war effort. They prepared care packages containing toothpaste, toothbrushes, food, whatever the soldiers needed. When the army announced a blood shortage was approaching, the volunteers made their way to donate blood that would be sent to the wounded soldiers up north. The Hizbullah rockets could not crush the spirit of volunteerism.

Volunteerism is built into Israeli society. Young women of eighteen who choose not to serve in the armed forces for reasons of religious modesty, will volunteer for two years in a program called, Sherut Leumi; National Service.

In Operation Protective Edge, Or Shachar, 18, volunteered with security forces and medical emergency teams. Yam Pozner, 17, helped run activities for children. Gan Yavne mayor: “If our future is going to be shaped by this generation, we are going to fare extremely well.” In Gan Yavne, near the Gaza Strip, where residents had to run for cover several times a day, dozens of teenagers ran day camps for children, took them on excursions during lulls, patrolled the area with local security forces, took care of elderly and immigrant families, and responded to medical emergencies with first responders.

Amit Malul, 17, has just graduated from high school and will spend the next year volunteering with various projects ahead of her army service. During the operation, she helped collect donations for Givati brigade troops. She also helped run day camps for new immigrants. Most of the activities were held in bomb shelters (Yisrael Hayom, July 6, 2015).

Appreciation on the part of the general population, and their desire to help, is perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the people’s army; the feeling that you are fighting for your people and they fully appreciate you.

I recall a cartoon showing a young Israeli boy. James Bond walks by, the boy yawns. Superman walks by, the boy yawns. An Israeli soldier walks by and the boy’s face lights up. They are the real superheroes.

As a nation of warriors, Israel embraces all its soldiers. Soldiers lacking in basic education will be provided with one, soldiers with special needs will be accommodated. Because serving in the military is considered so important sociologically, every attempt is made to include everyone who wants to serve.

Many handicapped individuals serve in the military; there are many jobs that they can handle. Autistic and mentally disadvantaged people also serve. They will wear a uniform, do some task, and feel that they are a part of the army and are serving the country. Israel recognizes that as much as the soldiers do for the army, the army does for them. The army makes you part of the family and the family takes care of all its members, including those who have physical or mental handicaps.

Many young people come from abroad to serve in the Israeli armed forces. They come alone—without family. The army takes care of them. Israel’s Lonesome Soldier law gives special benefits to soldiers whose parents left the country, soldiers without the support of a family such as orphans, soldiers who have no contact with their families, and soldiers from very poor families who cannot assist financially.

Lone soldiers receive a monthly stipend in addition to their standard military pay. This is double the amount other soldiers receive. On the holidays they will receive special gift certificates, and, once during their military service, they will receive financial assistance to visit their parents abroad, in cases where the parents are abroad. In addition, if the soldier needs housing, he will receive either a place to live or financial assistance to rent a place. This will be his home during his vacations. There are also kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz) that will adopt soldiers and provide a home for them during their military service. Many soldiers will remain close with their kibbutz family for many years to come.

The people of Israel have reached out to their lone soldiers to let them know they are never truly alone, that their sacrifice is very much appreciated. One such example is Beit Richman LaHayal, the Richman Home for Soldiers. An Israeli-American couple was watching a TV program about the lack of affordable housing for lone soldiers. They decided to turn a villa they owned into a home base for these soldiers. Today, it provides a warm and welcoming atmosphere for many soldiers. With fresh cooked meals and all the comforts of home, the lone soldier is not quite so alone anymore.

In 2006, Allen Garfel of New York came to Israel for a year abroad program. During that time he decided to enlist in the IDF. He served in the paratroopers unit and was injured in Lebanon in the battle of Ayta al Shaab.

During the Second Lebanon War, three lonesome soldiers were killed; Michael Levin of the United States, Yonatan Vasliuk of the Ukraine, and Asaf Namer of Australia. The lonesome soldiers are known as being particularly idealistic and motivated. Today, there are about twenty-four hundred “lonesome” soldiers serving in the IDF.

Yahtza

One of the best known and unique Israeli volunteer organizations is Yahtza, the National Search and Rescue reserve unit. The unit is made up entirely of volunteers. These are men and women who are veterans of the IDF and possess special skills in areas such as the medical field, construction, use of power tools, and other skills that are useful in disaster zones. Volunteers sign a contract allowing the army to call them up whenever they are needed and for as long as they are needed. Due to the nature of the work, there is usually no notice at all. The volunteers simply must drop everything and go, for however long it takes.

The unit operates both in Israel and abroad. It was developed for our local needs, but soon it became apparent that the unit was needed around the world. The unit has seen action in many countries. One such country was Haiti.

The Jerusalem Post reported on the story of one of the volunteers. “Captain (res.) Nir Hazut is a lawyer who, after having been wounded in Lebanon while serving in the combat engineering corps, had to fight the system in order to be allowed to do reserve duty. When he found out about the unit he did everything he could to be a part of it. His first time on a mission was in 2010, when he was part of the delegation sent to Haiti following the country’s overwhelming earthquake” (Jerusalem Post Magazine, October 14, 2011, 11).

Hazut and his team arrived at the scene; it was already the fourth day after the earthquake and the local rescue workers had given up. There was a man outside who said he knew his cousin was still alive, but no one was willing to risk going into the collapsed building. Hazut and his team went in. Seven and a half hours later they emerged with the cousin who had been buried alive.

In Turkey, a similar situation took place. The locals had given orders to stop the rescue operations because of the risk of aftershocks, but the Israeli team refused and ended up saving the life of a young girl. The girl was eventually brought to Israel for advanced medical treatment.

Even in cases where there are only bodies to recover, the unit operates in a special way and tries not to damage the bodies. It is part of Jewish tradition to bring the body to the grave in as complete a state as possible. The value and respect for human life, whether in Israel or abroad, is what motivates the unit to go to extraordinary lengths to save a single life.

ZAKA

One of the most famous and noble organizations in Israel is Zihuy Korbanot Ason (ZAKA), “Disaster Victim Identification.” Whenever there is a terror attack, a suicide bombing, an explosion, a shooting—the men of ZAKA are on the scene. Tragically, they have become all too familiar to the Israeli public.

It all started in 1989 when an Israeli bus was attacked by an Arab terrorist and fell down a hill, killing many people. Members of the nearby town, all religious Jews, swarmed down and tried to help. They tried to save the living, provide medical care to the injured, and carefully collect the body parts of those no longer alive—in keeping with the Jewish value to try to bring a person to the grave with as much dignity as possible. As such, there is an attempt to collect as much of the body as possible. Over the years, this spontaneous group action turned into one of the most celebrated volunteer organizations in Israel. Their members carry beepers and are on call 24/7. Today, ZAKA has over fifteen hundred volunteers throughout the country.

CHAPTER 3

Secret Ingredient of Israeli Defense

In the old story of the fox chasing the rabbit, a wise man is asked, “Who will prevail?” He answers “The rabbit. The fox is fighting for his dinner while the rabbit is fighting for his life.”

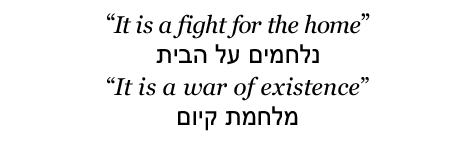

I wrote the following words on August 8, 2006, in the midst of the Second Lebanon War, which was really just a continuation of our enemies’ unsuccessful attempts to destroy us.

The Israeli army, Israeli self-defense, is fierce. We are surrounded by enemies who day and night seek our destruction; we have no choice but to be better fighters. Our secret ingredient is our motivation, spirit, and necessity. We are a peace seeking nation. Every war this nation has fought was forced upon us. Each war is a war for existence and survival. We fight, therefore, we still exist.

Two boys were killed in combat this morning; Philip and Noam. One came from Russia, the other from the United States, both reclaiming their national heritage, both descendants of those exiled by our enemies of many years ago.

Philip lived in my town, Maaleh Adumim. My mother is close to his mother. We were in the car when we heard the 11 am news, “The news from the front…killed in action this morning…and Philip Moscow of Maaleh Adumim.” My mother shouted, “That’s Luba’s boy! Oh my God, poor Luba!” We pulled over to the side of the road to digest the tragic news. Living is a game of Russian roulette.

Philip Moscow (left) medic, paratrooper, with captured Hizbullah

flag. Photo: Arie Katz

You ask why we fight, and why we fight so well; because if Philip and Noam, and all the other boys, were not up there fighting, then the enemy would be at the gates of our towns as they were before, before we had an army. The enemy would be in our homes, as they were in Hebron in 1929, slicing open pregnant women, slitting the throats of old rabbis and young students, raping women, smashing the heads of babies against the wall, massacring entire families as their shrieks cry out to heaven. We have seen the enemy.

So we fight because we must. And Noam and Philip are holding strong, knowing the extreme danger they face, because they are fighting for their families and friends, they are fighting so little children do not have to spend their childhoods in bomb shelters, so old people can finally enjoy some peace, so our weary people can enjoy a moment of rest. They are fighting to fulfill the words of the prophet Zechariah who wrote, “And it will still come to pass that old men and old women will sit in the streets of Jerusalem, and a man will lean on his cane for he has reached a ripe old age, and the streets will be filled with little children playing in her streets” (Zechariah 8:4).

And today, their time ran out. As I write these very words, Philip, of blessed memory, a young man of twenty-one, is being buried in the military cemetery in Jerusalem. Today they returned their souls to heaven and left grieving families who will never recover.

But their spirits will not die. Another soldier will pick up the rifle or the medical kit of Philip, the combat medic, and continue. He will continue; running into battle without fear. He will continue as the defender of Israel. The torch will be passed on and the request of the dying soldier fulfilled:

“I fought as long as I could; I gave my life, now it is your turn to protect our people. Carry on.”

Philip has returned home.

Thousands of years ago our people were exiled from our land by overwhelming enemy forces. In the exile, our people were persecuted and massacred, yet we survived. In Russia, an evil government arose that tried to estrange us from our age-old religion. For years, they did not allow our people to return home to Israel.

Finally, Philip returned home. He was overweight and was rejected for military service, but this did not stop him. Although he volunteered with the Civil Guard and the emergency medical services, he wanted to serve his people in the army. Nothing would stand in his way. He lost an enormous amount of weight and qualified for combat service. He served in the combat zone of Lebanon, treating injured soldiers, until an antitank missile hit his armored personnel carrier.

Less than a year later his younger sister would join the IDF. We all serve.

Close to four thousand years ago, the pharaohs of Egypt were determined to wipe us out. Many have tried since. But we are a stubborn, stiff-necked people, motivated and spirited. The people of Israel, despite all odds, lives.

1973, the Yom Kippur War, the October War. Despite a surprise attack by a well-prepared, Soviet-trained army, the IDF managed to thoroughly defeat and rout the Egyptian army.

One of the keys to the outcome was the leadership factor. With some armies, when the commander is killed or disabled, there is no one who can really step into his shoes and take charge effectively. In Israel, each member of the unit is trained as a commander. If the commander is no longer able to function, the next in command immediately fills his shoes, even down to the last soldier.

Each soldier is trained to use what he has available. They know that the situation in the field may not be ideal, so they train to adapt to whatever the situation may be. The saying is, “Tough in training, easy in battle.” Regardless of the number of soldiers, the type or amount of equipment, the position of the forces, the terrain, or the weather, the soldiers will know how to adapt. Leadership and independent creative thinking helped the soldiers continue with effective combat even after key commanders were no longer able to function.

In the 1973 war, the Egyptians initially took several Israeli positions. Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir had decided against a preemptive strike, such as the one Israel used successfully in 1967. She was concerned about world reaction to “Israeli aggression.”

Overwhelming Egyptian forces crossed the border with Israel. When the Egyptians finally managed to conquer a small post, using hundreds of soldiers and dozens of tanks, they were amazed to find the Israeli defenders had held out so long. They found a dozen soldiers, half of them injured, using a few semiautomatic weapons. The surprised Egyptians looked fruitlessly for the “hidden” weapons used to hold them off for so long. They could not find the weapons since these “weapons” were in the hearts of men.

This type of training manifests itself in everyday Israeli life and in Israeli self-defense. Success in self-defense does not depend upon any particular technique or weapon, but on responding to whatever the circumstances may be, just as in military combat. The situation is unlikely to match the ideal training environment, so the training environment must match the chaos and uncertainty of real life. An Israeli self-defense practitioner is trained to think on his feet and, as Bruce Lee said, “To respond as an echo.” We learn to thrive in chaos.

Interviews with soldiers from around the world reveal a low level of idealism. They were sent to fight wars they did not understand. Even heroes will often say, “I was just trying to save my buddies and get home alive.”

In the American Revolutionary War, soldiers truly felt they were doing God’s work. They were building a new nation and fighting for freedom. They were protecting their fellow citizens from tyranny. They were true patriots and often served without adequate food or pay. Letters reveal that these early Americans were true patriots; fighting for a cause they understood and believed in.

In Israel, that spirit still exists. Soldiers interviewed during the battles in Lebanon knew they were risking their lives. They were pulled out of university or taken from their jobs; they left businesses and families behind, some even flew home from overseas vacations and reported to their units. The interviews reveal the same answers again and again, “We are fighting for our homes. The people back home depend on us; we will stay here as long as it takes.” “This is a war for survival; this is a war for the home.”

Ordinary people, thrust into battle, find themselves acting as the saviors of the nation, protectors of the people. This develops in them a feeling of patriotism and self-sacrifice that will permeate their lives and affect their future. It will also develop a unique bond with their nation, and a feeling of trust between the soldiers.

When your life depends upon your fellow soldiers, you learn to trust them, you have no choice. You rely upon them and they are counting upon you. The self-sacrifice to save a fellow soldier manifests itself in superhuman courage and bravery. Running under enemy fire to rescue a soldier caught in cross fire, leaping into a burning tank to pull out a friend, even risking one’s life just to return a soldier’s body home to give it a proper burial, all these and more took place in the Second Lebanon War and in all the wars of Israel. The trust formed in such challenging times lasts a lifetime.

For about two thousand years the Jewish people did not have an army of their own. They used their economic leverage, persuasive skills, and whatever means they had to secure the temporary security and protection provided by their current host country. They were powerless to return to their own homeland, they were powerless to establish their own army. They could only dream.

The dream, the hope; to return home, to be a free people once again. The Jews of Europe had a poem called the Yidishe Medina (The Jewish State, in Yiddish), Dr. Theodor Herzl wrote a book, Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews, in German), the Jews dreamed of someday being masters of their own domain, free to defend themselves. When an Israeli soldier fights he may think of those days, not so long ago, when a Jew could not fight, when a Jew could not hold a military weapon, when only our oppressors had such weapons and they were pointed at us.

When I met with the families of our POWs, Yehuda Katz and Tzvi Feldman, I discovered that both boys were named for grandfathers who were murdered during the Holocaust. The grandsons went into battle carrying the legacy of their martyred grandfathers. They may have been feeling, “You were taken away, pushed into a ghetto, perhaps gassed, or shot, or suffered some other cruel death, your body may have been burnt in an oven, but I, your grandson, your namesake, am fighting proudly as a free member of the State of Israel, I am the fulfillment of your greatest dream.”

My brother, Ethan, served in a combat unit. Having a strong sense of Jewish history, he felt this message in a powerful way. He wrote, “I remember in basic training, we were on a long hike and my back was killing me and my arms were aching. I just wanted to throw down the gun and the heavy gear. Then I started thinking of what the previous generations of our people would have given to be in my boots, to carry an Israeli made assault rifle (a Galil) with close to three hundred bullets and a couple of hand grenades. I was thinking what would this have meant to Ze’ev Jabotinsky (legendary Zionist leader who wrote, “Jews! Learn to Shoot!”) and to Dov Gruner (Jewish martyr who fought to liberate Israel from the British who occupied this land) and the rest, and how much more this would have meant to the previous generation; what would this have meant to the warriors of the Warsaw Ghetto. I realized that in reality I was living the dream of thousands of years of Jewish fighters; how dare I complain about some aches and pains” (Ethan Katz, from a personal letter).

My nephew, Arie, the paratrooper, was named for his great-grandfather, Aryeh Yehuda Landau of Poland. When his grandmother Rachel was four years old, the Nazis came to their home and took her parents away. She never saw them again and to this day has never learned their fate.

Rachel survived the worst of the concentration camps, made it to Israel, served in the IDF, and raised a family. When Arie visited Poland with his high school, as part of the March of the Living program, he recited the Jewish mourners’ prayer, the Kaddish, in honor of his great grandparents. I believe that when he enlisted in the Israeli army he elevated their souls and fulfilled their dreams. He is the embodiment of all they could hope for. He brought them the greatest comfort and pride. When we fight, we fight not only for ourselves, but for all those generations who could not, and for all those future generations who should not.

Israel is known for going to great lengths to retrieve prisoners of war. So much so that it is seen as a weak point by our enemies. Often Israel will exchange thousands of Arab terrorists for one Israeli soldier, and in many cases it will turn out that the soldier is already dead. Israel places such an emphasis on human life, even after death, that it weakens our bargaining position. Often dozens of live terrorists have been exchanged for the body parts of an Israeli soldier. Even this is considered part of our policy of “bringing the boys home.”

In my community of Maaleh Adumim, an unprecedented act of nationalism took place. The town is known for producing many elite combat troops, devoted body and soul to the cause of Israel. In May 2011, a group of pre-army teens came out with a signed declaration, “If we fall captive to the enemy do not release terrorists with blood on their hands in order to free us.” This took place during the great national debate over the negotiations for the release of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who was held hostage by Arab terrorists. The debate centered around the question, “How many do we release for one soldier?” If we release terrorists with blood on their hands, i.e., those convicted of murdering Israelis, these terrorists will return to active duty, today, and will try to kill again. So as much as we want to free one soldier we must be aware of the cost; the likely death of many more Israelis. These pre-army teens in Maaleh Adumim felt it was in the national interest that if, God forbid, they fell into enemy captivity, Israel should not release convicted terrorist murderers to secure their release. Imagine—these boys were saying they were willing to stay in captivity indefinitely rather than cause harm to the citizens of Israel! Can there be a greater sacrifice than this! Tomer Mendel, one of the organizers of this act, and a Krav Maga student of mine, stated, “I do not believe that releasing a thousand terrorists is the way to free Gilad Shalit. The State of Israel should have pride, and I am not prepared, if I were to fall captive or taken hostage, that the State should hurt its national interests in order to release me” (Zman Maaleh, May 26, 2011).

CHAPTER 4

Warriors from Childhood

I was having some trouble with the neighbor’s kid. I asked my dad to take care of it for me. After all, he was my dad and that is what dads do. He said, “Son, you have to learn to fight your own battles.” That was many years ago, but I have never forgotten that lesson. Truly we must all learn to fight our own battles.

We are not just a nation at war. We are involved in a special kind of war. Some call it “The War against the Jews.” This war has been going on for a long time and has seen many enemies—the ancient Egyptians, Philistines, Babylonians, Romans, Crusaders, Cossacks, Nazis, the modern Egyptians, and all the other Arab nations. We not only have enemies at our borders, we have enemies within our borders, and beyond our borders—hard core terrorists.

The opponents change, but the war remains. This is not an easy concept to grow up with—the idea that you are hated. But we learn early on that we must be prepared to fight or we will suffer as previous generations of our people have suffered, for in every generation “An enemy rises to destroy us” (Passover Haggadah).

We must never be unprepared. From the time a boy is very young, he knows that when he turns eighteen he will be a soldier. To get out of the draft is considered a mark of shame that follows one for the rest of one’s life. When I was interviewing for a job, every interview began with the question, “Where did you serve?” At least in my circles, a courtship and a friendship involve that question. Everyone knows where their friends served. People define you by where you served. Were you in a combat unit? Did you serve in intelligence? Were you in the air force or the navy?

For many it will be the pride of their lives. They may work many years in meaningless unfulfilling jobs, but they will think back with pride to their days in the military, to the days when they led brave men into battle.

Friendships formed in the army will create a bond that lasts a lifetime. A warrior will always be there for his brother warrior. He may turn old and gray, but to his brother warriors he will always be eighteen. They will remember him as a young warrior—they will reminisce about the days when they stopped the Syrians in the North or the Egyptians in the South.

Speak to just about any sixteen or seventeen-year-old Israeli boy or girl and they will already be experts on the different units and what it takes to qualify for each one. They will know how long and how difficult basic training is and which units have the best reputation. They will be able to identify each unit’s symbol and tag.

Most high school students are involved in some sort of pre-military training to prepare them for military service. This is not mandatory—it is done on a private basis outside the framework of the IDF. Gyms are filled with seventeen-year-old boys. You will find them lifting weights, hitting the heavy bag, and doing push-ups. Late at night you will see teenagers running up hills, sprinting—they are getting ready for Lebanon and Gaza. They want to be the best. They dream of being in the top, most elite combat units, but some are placed in support roles such as logistics, ammunition, or repairing weapons. Sometimes, in Hebrew, this is referred to with the rhyme “ha moach me’achorei ha koach” or “the brains behind the brawn.”

There are many organizations and programs, like college prep courses, that promise to train the boys and help them get into the best units. There are also programs run for free by veterans who just want to help. One organization is called Aharai! Follow me! This slogan is used by Israeli officers who lead their troops into battle. Israeli officers lead from the front, not from some far-off post or in the back of the troops. Israel has a high rate of officer casualty because officers are the first to face the enemy.

The Aharai! Follow me! organization started more than ten years ago when a discharged combat officer was walking through a poor neighborhood. He saw a group of high school students training on their own to prepare for combat units. He offered to train them, for free. Over the years, this group has grown and now has branches in more than one hundred locations throughout Israel (a state smaller than New Jersey). The group prepares high school students for military training, tours the country, teaches the history of this ancient land, and volunteers by helping needy communities. At the end of the course, the participants sign a declaration to serve faithfully in the army and continue as community leaders after completion of their service.

In the various youth movements a great deal of time will be devoted to hiking and getting to know the land. The nation’s history will be learned and will become part of their individual psyche. They will walk where the biblical Abraham walked, they will stand where Joshua stood before attacking Jericho, they will see where King David fought, they will relive the battles of Israel from biblical times to our own and they will hear the stories of heroism. They will learn how to use a compass and “read” the land. They will hike on difficult terrain and cook their food outdoors. It is all fun, but it is also pre-military training. They will feel the thread that weaves from ancient history to modern challenges, they will live Jewish history.

After regular service is completed, many will sign on for a few more years or for a career in the military. All will continue to serve in the reserves. They are a people’s army; plumbers and farmers, accountants and teachers, ready to be called up at any moment, change into their uniform and become the saviors of their people. There is a code of honor, an unwritten pact: when you need me—I will be there.

During my college years, a former soldier came to speak to us, something about him stood out—he had only one arm. He said words I will never forget, “When my people needed me I dropped everything and reported for duty. Now I am no longer able to fight, my arm was shot off; I can no longer defend my young children. It is now your turn, you owe it to me.”

Soldiers will meet in the reserves over the years; their families will meet. And tragically, those many families who have lost a father, a son, a brother, will mourn forever, keeping the photos and awards of the fallen soldier proudly displayed for all to see. When a young member of the family comes home for his first vacation from the army, the older members will compare notes about everything from the type of weapon used to the food served in the kitchen. Stories will be exchanged. The military is a thread woven into all aspects of life. Military expressions are a part of everyday life; to “return equipment” means that something has come to an end. Military time (using 1400 instead of 2 pm) is in standard use. One of the frustrating aspects of this society is that you can come to pick up your laptop from the repair shop and find a note “Owner has been called to the reserves, back in three weeks. Sorry.”

Every mall and restaurant in Israel has security guards and most are armed with a handgun or a short rifle. The larger establishments have metal detectors. Customers are searched and bags are checked. Roadblocks line the highways; cars are stopped, trunks are opened, and identification papers are requested.

From a young age, we are taught not to pick up a cigarette box or button from the floor. As a child, I recall we had a poster on the wall with pictures of boxes, buttons, and various toys. The caption read, “Suspicious objects: don’t touch, it might explode.” From time, to time a security expert would come and talk to us kids about the dangers in the world. Caution became part of who we are. Even now, I will never pick up a box of cigarettes or a matchbox from the floor, despite my tendency to clean up and to be a good citizen.

A bag must never be left unattended, if it is, it is assumed to be a bomb and the bomb squad will be called. You will not be reimbursed for any damage done to your personal possessions; you are to blame for your careless negligence. An American tourist showed up at a bank to cash his traveler’s checks. The only problem was the checks were filled with holes. “What happened here?” the teller asked. The tourist said he put down his backpack for a few minutes and went to get a drink. When he returned, the entire area was roped off and the bomb squad was detonating his bag. His checks were damaged in the controlled explosion.

Blowing up abandoned articles is standard. One often hears the expression “suspicious object.” You can be walking along King George Street in Jerusalem when you find a crowd gathered and no one proceeding. “What’s going on?” you ask. The answer comes in the expression that all understand, “suspicious object.” No further explanation is necessary. We are used to this kind of alertness and security; it becomes second nature.

To complain about delays is practically unheard of; people understand that national security is more important that anything you may have to do. Suddenly life takes on a different perspective. Your personal errands no longer seem so crucial. Employers readily accept “suspicious object” as a valid excuse for being late.

I recall when I came to train at Karate College in the United States—we were all lined up for registration. I had my heavy duffle bag on my back and my carry-on bag in my hand because “one never leaves a bag unattended.” Then I noticed something strange—I was the only one doing that. Everyone else had piled up their bags next to a wall and proceeded “bag free” during the long registration process. I could not understand this lapse in security. How could martial artists leave their bags unattended? How could they be so careless? For us, any bag unwatched for a few minutes can no longer be assumed to be safe—it must be examined by an expert.

Children here in Israel enjoy watching the robot that bomb squads use to pick up a suspicious object. They watch it place the suspicious object in the “security hole” and then detonate it. We understand what is going on. This has the effect of creating a nation of very alert and careful people.

Many stories have been told of Israelis spotting suspicious activities while on vacation abroad and alerting others. Like trained detectives, they are looking out for something that is a bit out of the ordinary, a sign of trouble. We learn to listen to things that “go bump in the night.” By the time an Israeli begins his military service, he has already had significant training in gathering intelligence, basic detective work, and spotting suspicious objects and characters.

An Orthodox Jerusalem man was walking along in his neighborhood of Mea She’arim when he noticed something odd inside a garbage can. He alerted the police. It turned out to be a large explosive, placed just a few feet away from a school where hundreds of children were studying.

When my brother was a newlywed, his English wife was shocked to learn that he slept with a handgun under his pillow. This comes as no surprise to an Israeli as we all do this in the army. We learn that a weapon is never, ever, to be left unattended; it must be kept under a double lock, never handed to anyone without a license. Carelessness with weapons will lead to long jail terms.

Before we enter a cab we try to verify the identity of the driver, Israeli or Arab. An unknown driver can be a terrorist looking for a victim. We check before we buzz someone into a building, we look in the peephole before opening the door. We have learned to be careful, the hard way.

A young man and his wife, new immigrants from England slept with their window open. We have an expression in Israel; “an open window invites a terrorist.” The inexperienced young man heard a sound and went to look. A knife-wielding terrorist climbed in. The man was killed that night. Another widow was created.

A student of Greek origin came to train with me in Krav Maga; he was only nineteen years old, but had the wisdom and knowledge of a much older man. There was something about him that struck a chord with me, like we had some deep connection. I finally understood that there was something very “Jewish” about him; carried Greek history in his soul, he felt the pain of Greek land occupied by foreigners, he bore the scars of massacres and expulsions that took place years before he was born. He was a serious person, as are Israelis.

This is a serious people. It is commonly said, “Israel is the only country in the world where ‘small talk’ consists of loud, angry debate over politics and religion.” Israelis tend to think less of some tourists, or some new immigrants, as being somewhat shallow and preoccupied with matters of insignificance. They talk about topics of little significance, debate matters of no importance. In Israel, even children have an opinion on politics; children know their history. Israelis get loud and angry when discussing politics, religion, and history because they care passionately about these topics. These are issues that truly matter in their daily lives; they are not indifferent about them.

National issues affect everyone. You care about national policies because it is you who will be sent to the border to defend them, you or your kids, or you and your kids. In many wars, fathers and sons are fighting at the same time, each with his unit. National policy affects us all, and we have an opinion we want to share; we feel we understand the issue at least as well as the prime minister and we should be heard. This is a democracy of warriors. We fight and we want a say in the decisions that affect our lives. So if you are going to argue with an Israeli, make sure you know your facts first, otherwise, as we say over here, “the women will eat you for breakfast.”

Foreign Krav Maga students who come to Israel to train often remark about the toughness of Israeli kids; the way they train, the way they fight. It is as if they are indeed warriors in training, their mental fortitude, their attitude, is already being prepared for combat. Perhaps it is seeing fathers, uncles, cousins, and older siblings preparing for military service. Perhaps it is the news, the ceremonies at school honoring the fallen, and stories about heroes. Or is it seeing guns everywhere; M-16 rifles, grenade launchers, and a variety of handguns? Perhaps it is learning our history, how we defied the odds and managed to survive war after war.

There is something in the air that makes kids grow up differently over here, they are not like their counterparts in Europe or America, you can sense it in their look, in their eyes. These are battle hardened kids. Somehow they know that at eighteen years of age they will not be trying to choose a major at college, they will be chasing down terrorists or protecting the citizens of Israel from a foreign invader. This knowledge permeates their childhood and changes their outlook. Like an animal in the wild, they are aware of danger and conditioned to respond, their survival instincts are honed. They develop an ability to take charge and respond, an ability that will serve them well in the military and throughout their lives.

Some people hope that “when my child reaches eighteen there will be no more wars, there will be no draft.” But we know this is not true, we know that another generation must be trained and prepared to fight.

Fighting off terrorists and other bad guys; stories of heroism, self-defense, and self-sacrifice.

Jacob, now in his mid-fifties, woke up that morning as any other morning, bright and early. He had the morning route for the bus company and could not be late. The route began as it always had—familiar faces, smiles, and greetings of shalom (hello); people on their way to work or school. This was before the days where most bus stops had armed security guards; the driver was alone with his precious cargo—his passengers.

Suddenly a passenger pulled out a knife and began stabbing. It was a terrorist who tried to take over the bus. Jacob pulled the bus to a halt and was upon the terrorist in no time. He sustained cuts, but disarmed the assailant.

TV crews interviewed the “hero for a day” and asked what went through his mind when he attacked the armed terrorist, wasn’t he afraid? “My military training just kicked in,” he said. “You know I was a fighter! I served in a combat unit. I came to the rescue of my passengers just as I would on the battlefield. I did not think of myself, I just reacted.” This self-sacrifice is not a conscious thought process. It is an instinct that is developed through military training and carried over into civilian life. One may take off his uniform, but his military spirit remains.

Imagine sending your child to school knowing that the bus driver is a trained soldier with combat experience. Once he drove a tank, now he drives a school bus. As your child walks into school, he walks past the school security guard, a recently released soldier from the Golani or Givati brigades. When your child enters the classroom, he is greeted by his teacher, formerly a member of an elite combat unit. The school nurse served in Lebanon and she completed basic military training and can take apart an M-16 rifle in minutes. The janitor is a special forces veteran; the principal was a tank commander. These are the people that make up your child’s day—this is Israel.

The story is so common that one cannot possibly remember how often it has occurred. Nearly anyone can be a hero for a day; nearly everyone has some training and experience. It is as if secret agents are hidden all over the country, dressed as ordinary people, waiting to be activated by a secret signal.

You could be sitting on a bus, surrounded by ordinary-looking people, some old, some young, some male, some female, some Israeli born, some with foreign accents. You do not know who they are, but I can assure you of this—each one has a story to tell. One young fellow has a plastic leg; he lost his leg while fighting terrorists in Gaza. Another fellow was among the first to cross the Suez Canal back in ’73 under Egyptian artillery fire. Most of his unit was hit, but he survived and is still traumatized. An old gray-haired woman was a messenger for the French resistance against the Nazi occupiers. An old man fought at the Battle of Stalingrad in Russia and has many medals for valor and courage. His Hebrew may be weak, but he carries himself with an air of dignity, he is a warrior. Yet another survived the ghettos of Nazi occupied Europe, escaped to the forest where he joined the partisans and fought the Nazis, joined the illegal immigration movement, challenged the British blockade, came to Israel to fight for independence, defended his kibbutz against Arab raiders, and lost a son in the 1967 Six Day War. Another fellow, young and “wet behind the ears” recently led his troops into Gaza and liquidated a terrorist cell. You show respect to all, because, despite their humble appearances, you are among true heroes.

This is a nation that has fought on countless different fronts, speaking numerous different languages. There are Polish-speaking Jews who fought the Nazis and held out for longer than the entire Polish army. There are French-speaking Jews who sabotaged Nazi war efforts and blew up their trains and railroads. There are English speakers, veterans of World War Two, who came to Israel to volunteer and helped form the Israeli air force. There are Russian speakers who served for years in the Russian military. There are Amharic speakers from Ethiopia, serving in elite combat units.

An eighteen-year-old girl, serving with a combat unit, put the “makeup” on “her boys” before they went out for their big nighttime operation against terrorists, and cried out to them, “Every one of you is coming home, you understand! Do you hear me? You are all coming home!”

You show respect because any of the people you bump into could be a hero. You show respect because it is these people who allow us to lead normal lives as a free and independent people.

During a flight to Turkey, a knife-wielding terrorist attacked a flight attendant. His goal was to use her to get into the cockpit, take over the plane, and fly it into a tall building in Israel.

The flight attendant surprised him by using evasive movements to avoid his slashing attempts. She later admitted she was terrified. Her delaying tactics gave the armed security guards the opportunity to subdue the terrorist. No one was hurt. Passengers remarked that during the episode the flight attendants were “very cool, they calmed us down.” The crew consisted entirely of former soldiers.

The female flight attendant used evasive movements, as taught in Krav Maga, to avoid the knife and buy some time. Disarming a knife attacker is very difficult, it is better to use body movements and just get out of the way. The idea behind evasive movements is to move that part of the body most imminently threatened, e.g., if it is to the head, pull your head back, to the stomach, pull your stomach in, to the leg, jump back. While doing this, keep your forearms in front of you as a barrier. The forearms can take a potential cut, but much better than your wrist, neck or stomach. Her quick movements saved herself and possibly all those on board and many more on the ground.

Following obligatory military service, three years minimum for men, many begin their university studies. As a result, nearly all university students are in the reserves and can be called up at a moment’s notice. Naturally, this causes disruptions in their studies. Due to this situation there are always three different dates for final exams in order to accommodate students called up for reserve duty. A student can be in the lecture hall one day listening to a professor and taking notes and then within forty-eight hours be on the battlefield listening to his commander and loading his tank. Walking to the mailbox to pick up his mail, the university student is always aware that finding a brown envelope with a military stamp means, “I’ve been called up again!”

Recently, the IDF pulled off a daring raid and in a bloody operation eliminated a dangerous terror cell that had cost us many lives. The leader of the operation was praised for his bravery and professional undertaking of the operation. “What are your plans now?” the press asked him.

“Well, I was immersed in my biology studies before I got this call-up. I was studying for a major exam and the pressure was really getting to me. This has been a welcome break and now I feel I am ready to return to my studies. I just hope my professor accepts my excuse for missing the midterm.” Within a few days, he was just another student in the classroom. In Israel, you can be sitting in a lecture hall, never realizing that the young man sitting next to you is a real-life Rambo.

After military service, many young men take a “light” job, something that does not involve too much thinking, something to ease their way back to civilian life and make a few dollars (actually shekels) so they can afford a trip abroad. One such man was working as the main waiter at Caffit; a popular coffee house in Jerusalem.

One day, one of the customers trying to get in aroused his suspicion. Based on the art of profiling—judging his accent, body mannerisms, a touch of nervousness—the waiter decided to jump him. Single-handedly and without warning, the waiter immobilized the man, who turned out to be a terrorist. He had several pounds of explosives in a “suicide bomber belt” around his waist. The lives of the coffee house patrons were saved.

If you are tackling a suicide bomber on your own, you must grab one of his arms, swing around the back and grab his other arm. Speed and the element of surprise are crucial. Pull his arms up and lock them from behind. Actually, the most important ingredient is courage.

The next day the waiter returned to work as if nothing had happened. To his surprise, he opened the mail one day to find a check for five thousand dollars. It was sent by an American supporter of Israel who wanted to reward the “everyday, soon to be forgotten, heroes.”

Eli was interested in martial arts. After his compulsory military service he traveled to Thailand and trained in Thai boxing. He returned to Israel and hoped to open a gym, but did not have the finances to do so. He got a job as a security guard at a Tel Aviv nightclub, Zigota. The job of a security guard is not easy, standing long hours for little pay, closely eyeing hundreds of people, wondering who might be a terrorist. One night he saw a vehicle driving toward the club. By the nature of the speed and angle of the driving, Eli evaluated the approach as a suicide attack. Dozens of club goers were outside the club waiting to get in. Eli reacted quickly and opened fire on the driver, killing him on the spot. An explosion went off in the car. After examining the vehicle, police discovered large quantities of explosives. The driver, an Arab terrorist, planned to crash his vehicle into the partygoers and set off the explosives, causing massive damage. Eli’s quick thinking and rapid fire saved countless lives.

During basic training, one learns many essential skills, such as taking apart and cleaning various types of weapons, and how to clean the latrine. Equally important are the lessons on attitude, moreshet krav, (fighting heritage). We are taught that regardless of your official position, tank driver, cook, intelligence officer, you are first of all a soldier and you must always behave as one. You might be a military doctor or a computer expert, but you are first a soldier and you must possess the attitude, training, and the fighting spirit, of a soldier. You must possess the initiative and “take charge” attitude of a soldier. You must be able to lead when leadership is required. To illustrate this point, we were told of an incident where terrorists managed to infiltrate a base. It was the early hours of the morning and the cook was busy in the kitchen when he heard something. The career cook grabbed his M-16 rifle, went outside carefully, took cover, and opened fire. He eliminated both terrorists.

In the army, it is ingrained in us—your rifle must always be within arm’s reach: you sleep with it, eat with it, go to the bathroom with it, and shower with it. At all times, you are a warrior. This attitude translates into everyday life, as civilians, all soldiers in the reserves, are alert to potential danger and suspicious behavior.

“It is Not the Age, it is the Attitude,” read the morning papers. A young thug tried to rob a post office. Two customers waiting in line—a retired schoolteacher and a retired plumber—thwarted his efforts. The plumber, a man in his seventies, jumped the young thug from behind while the retired school teacher, a woman in her sixties, joined in and grabbed his legs. Together the two subdued the attacker. Later, when they were interviewed, they said, “This is my branch, I like the people here, I could not stand to see some kid come in and rob this place. I just reacted without thinking of my personal welfare.”

Israelis are used to the sudden sound of terrorist activity and react quickly. Case in point: Eli, an insurance agent working in his third floor office in downtown Jerusalem. Eli heard an explosion. He immediately raced down the three flights and out to the street. He spotted two terrorists and drew his personal handgun that he always carried. He opened fire and hit one of the terrorists. He chased the other one and fired, but his gun jammed. Eli caught up with the terrorist, smashed him over the head with the butt of his gun, knocking him to the ground.

Eli was not just a mild-mannered insurance salesman. He was a commando soldier in the reserves. In an instant, he was able to make the mental switch from businessman back to commando soldier. Whether it was the Sinai desert where he fought during the 1973 Yom Kippur War or downtown Jerusalem, the same mental training and attitude guided him.

In another incident in Jerusalem, two friends, both members of the military border police, were casually strolling down the street when they spotted terrorists. They drew their sidearms and opened fire. What followed was a classic Wild West style shootout in a modern urban center. At the end of the exchange one terrorist was dead and the other injured and taken into custody.

I was in a lawyer’s office to sign some documents. I tend to look at the walls while waiting, and read the diplomas. I noticed several diplomas that did not fit in with your standard law office. These spoke of “bravery in the service of mankind,” “saving lives during terrorist attacks,” and “excellent emergency care under fire.” I asked Dror, the lawyer, about these diplomas. He smiled, ever so modestly, and said that although he had a busy law practice, one day a week he was an emergency paramedic. As such, he was often called to a scene seconds after a bomb went off, or as a shooting was taking place.

He said he felt like he was continuing his military service, his national service; he was helping his people in a real hands-on kind of way. I looked at the walls of his office and saw photos of his family, a wife, and six children. Surely this man needed to make a good living to support his large family, surely it cost a great deal to put six children through private religious schools. And yet, he found the time to leave a successful law practice and run to the scenes of suicide bombings and other attacks. Just to view such scenes is horrific, and yet he did it. He was, to me, one of the unsung heroes of Israel, and there are countless others. They go through life nearly undetected, giving of their time, putting themselves in the line of fire, seeking no reward. It gives one hope for mankind.

It was October 1973, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the most solemn day in the Jewish religious calendar. I was, of course, in our local synagogue, praying with my father and brothers. It is a difficult day; no food or drink allowed, just endless praying.

The Egyptians must have thought of that when they decided on a surprise attack on that special day. We sat in the synagogue, in prayer, totally unaware. Gradually the synagogue began to empty. Men walked out in the middle of prayer and didn’t return. Rumors began to circulate.

By the afternoon break, we knew what was happening. Once again our enemies initiated a war, violating our holy day. Details were still blurry, but the flow of men from the synagogue told us everything we needed to know. Once again, the men were leaving the house of prayer and heading for war, a war that would cost us nearly three thousand lives.

Most of my teachers would not return for many months. One popular teacher would write us postcards that were posted on the school bulletin board. I remember the day the postcards stopped coming and we heard the sad news; he would not be returning; he had been killed in a battle on the Egyptian front.

Most of us students used our free time to volunteer and fill in for men who were called up. We picked crops in the kibbutz fields, painted car headlights (so enemy bombers would not spot them at night during the blackouts) and I delivered the mail for a while. All the regular workers were on the front lines.

Gradually, school resumed. Our substitute teachers were mostly older men who were over military age. It was a somber year. Kids canceled their customary bar mitzvah celebrations. Our whole attitude toward life changed. Everyone had a father, an uncle, an older brother, in the service.

My father, although over the age for combat duty, was called up. He served in connection with the home front. Nearly everyone served in some way. Over the radio we would hear code commands such as “black crow report to base,” and “mother bear return to den.” We knew this meant more reserve soldiers were being called up. Air raids would send us running to the nearby bomb shelters.

The thing I remember most was that first day—when men had to put away their prayer books and pick up their rifles. These were the everyday heroes—the men at the local synagogue, our schoolteachers and our mailmen—who pushed back the Egyptians and the Syrians and kept us safe.

A knife-wielding terrorist broke into a Jerusalem high school. He did not know that this was a school for “challenged” kids with discipline issues. These troubled kids had dropped out of most regular schools. Before the terrorist knew what was happening, a bunch of eager teenage boys were all over him. The terrorist realized he had just attacked a hornet’s nest and tried to escape, but was pursued by the students. The principal—it takes a tough guy to run this kind of school—grabbed a stick and joined the enthusiastic students. He too wanted a piece of the action. The battered terrorist was taken into custody. The headlines the next morning read, “Terrorist Picks Wrong School.”

Rona had mistakenly allowed a “nice boy” into her dorm room, to “watch a video.” She had taken some Krav Maga classes, “As a precaution, since I had heard there are a lot of rape attempts on campus.” She learned a few basic techniques and practiced them occasionally.

When Rona’s date started making advances, she made it clear she was not interested. The rejected lover did not take no for an answer. He pinned her down and grabbed her throat. Rona saw the writing on the wall and reacted as she had been trained. She pulled his hands a bit to the side, to allow enough air in so she could breathe, and grabbed his throat and squeezed as tight as she could. As he recoiled from the pain she kneed him in the groin, pushing him off. She got up and ran out the nearest door. It turned out he had tried this before on a friend of hers, but the friend “did not want to ruin his reputation” so she kept it a secret. Rona was wiser; she reported him at once.

Samantha was sitting alone at a café while vacationing in Turkey. A local man saw this as an invitation. When she stood up and told him to take a hike, the unwelcome intruder grabbed her for a forced hug. She held on to his shoulders and thrust a powerful knee kick directly to his groin. He keeled over and walked away in shame. Samantha learned this technique from watching a movie on TV. In the movie, an abused woman used Krav Maga to defend herself and regain her self-respect.

Yaakov and Uri were off duty. They had finished their shift as security guards for a private company in the Old City of Jerusalem and were casually walking home when they noticed a group of somewhat drunk Arabs harassing a yeshiva student. They walked up and advised the aggressors to take a hike.

Instantly, the five Arab youths jumped on the two guards. One was knocked to the ground while two of the Arabs were kicking him and trying to get to his gun side. He knew there was a danger of them trying to grab his handgun. He rolled on the side of his handgun, thus protecting it from being taken away and used against him. Although he was getting severely kicked, he knew he must never leave the handgun exposed. His friend, using a spare magazine, managed to slash the face of the one of the assailants. The sight of blood freaked them out and they all ran. The yeshiva student and the guards were unharmed. Elite security guards are taught to conceal their weapon as much as possible while still being able to access it as quickly as possible. A shirt or jacket should always cover the gun; this makes it harder for someone to grab it from you.

A distraught man was holding a gun, pointing it directly at his family. He was unemployed and desperate and wanted someone from the government to come and speak with him. A security guard approached him and said he was, in fact, sent by the government. He signaled to another guard to come from behind and disarm the unfortunate fellow.

Vladimir was walking his dog in the valley of the Judean desert one evening when he spotted two unfamiliar men. They were Arabs. One extended his hand; the other was suddenly out of view. Vladimir responded by extending his hand in friendship. The Arab pulled him forward and stabbed him with his free hand. The second Arab reappeared and both stabbed Vladimir repeatedly. Vladimir managed to fight back and kick the knife out of one of the Arab’s hands. Both Arabs fled. Vladimir was stabbed thirteen times and nearly bled to death. Fortunately he survived.

Vladimir was caught off guard. What he should have done, despite the risk of appearing rude, was offer only a slight nod instead of a handshake. A handshake can prove very dangerous. Just because someone extends his hand does not mean you must take it. If someone does have a grip on your hand, there are many options open to you; you can strike the person with your free hand and then, using your entire body, twist out of the grip. You could strike him under his radar with a knee kick to the groin; this will loosen his grip right away.

I advise against hitchhiking, period. However, there are many places in Israel where public transportation is limited, and many young people do hitchhike. Israeli youth are fearless and believe this is their land, as God said to Abraham, “Arise, and walk through the land, the length and breadth of it, for to you I will give it” (Genesis 13:17). As such, they are everywhere, despite the dangers.

Two teenage girls from a religious academy near one of the settlements were waiting for a ride. A car pulled right up to the curb, the girls had been trained to be careful. As they took a look to see if the driver was a Jew or an Arab, the two Arab passengers in the back seat got out and tried to grab the girls and pull them into the car. The girls fought them off and managed to get away. Their alertness and fighting spirit made the difference.

At the entrance to the supermarket in the Beit HaKerem neighborhood in Jerusalem worked a trustworthy security guard, an older man trying to make a living. He noticed something odd, a young Arab girl, only sixteen years old walked over to an old Arab woman selling figs outside the supermarket. Very quickly the old Arab woman rose up, grabbed her bags of figs and left. The young girl then tried to enter the supermarket. The security guard stopped her and blocked her entry with his body. She detonated her bomb, killing herself and the security guard. He paid the ultimate price. No one in the supermarket was hurt.

Heroism by everyday heroes is not limited to Israeli soil. The unique spirit of this nation shows itself outside the borders of Israel as well. In the 2007 massacre at Virginia Tech in the United States where thirty-two students and faculty were killed by a student, Professor Liviu Librescu died fighting, as a hero, as a warrior.

A student in the French class described how the gunman walked into the class, went up and down the aisles just shooting people. He said, “Nobody tried to be a hero.” The teacher and many of the students were killed. (There is some speculation that the teacher attempted to barricade the door and stop the gunman, but she did not succeed, only seven students in the French class survived).

The story was quite different in Professor Liviu Librescu’s, engineering class. By blocking the door, he used himself as a shield to stop the shooter and give his students time. He had the clarity of mind to give his final lesson: jump out the windows, save your lives! All but one of his students made it to safety. Who was this man? He was a Jew, an Israeli, and a survivor of the Holocaust. His behavior reminds me of two similar incidents.

In Munich, Germany, 1972, the world’s finest athletes gathered to compete in the Olympics. It had been only twenty-seven years since the Nazi Holocaust and the memories, for the Jewish people, were still fresh. Many of the members of the Israeli team had lost relatives in the Holocaust, but those interviewed prior to the event looked on the Olympic games as a way of making a statement of defiance to the Nazi murderers of the past by showing the resilience of the Jewish people.

The day before the games began, the Israeli team visited the nearby concentration camp where Jews had been murdered. Fencing coach, Andre Spitzer, laid a wreath. He himself would soon join the list of victims of anti-Jewish hatred.

The Israeli team enjoyed a night out on the town, watching the play Fiddler on the Roof, starring a fellow Israeli. All seemed brotherly in the Olympic village.

The Arabs sent a team of their own; armed terrorists. With AK-47 assault rifles, handguns, and grenades, they entered the sleepy, peaceful village. As they tried to enter the Israeli athletes’ room Yosef Gutfreund, a wrestling referee, was awakened by the faint noise at the door, which housed the Israeli coaches and officials. He investigated and discovered masked men with guns. He shouted a warning to his sleeping roommates and threw his nearly three hundred pounds of weight against the door in a futile attempt to stop the intruders from forcing their way in. Gutfreund’s actions gave his roommate, weightlifting coach Tuvia Sokolovsky, enough time to smash a window and escape.

Wrestling coach, Moshe Weinberg, fought back against the intruders, who shot him through his cheek and then forced him to help them find more hostages. Leading the kidnappers past the apartment with more Israeli athletes, Weinberg lied to the kidnappers by telling them that the residents of the apartment were not Israelis. He risked his life to save his fellow Israelis. The wounded Weinberg again attacked the kidnappers, allowing one of his wrestlers, Gad Tsobari, to escape via the underground parking garage. Weinberg, a powerful man, knocked one of the terrorists unconscious and slashed another terrorist with a fruit knife. Another terrorist shot him to death. Moshe Weinberg died a hero’s death, fighting back and saving the lives of others. He died a warrior. Inside the apartment, weightlifter Yosef Romano, a veteran of the 1967 Six Day War, attacked the intruders, slashing terrorist, Afif Ahmed Hamid, in the face with a paring knife and grabbing his AK-47 away from him before being shot to death by another terrorist. Romano’s bloodied corpse was left at the feet of his teammates all day as a warning. Yosef Romano died a hero.

Other Israeli members were awakened by the screams and warnings and managed to escape. The two women on the team were housed in a separate part of the Olympic Village inaccessible to the terrorists. Two Israelis died hero’s deaths while nine more were taken hostage. In the failed West German rescue attempt, several terrorists would be killed, but so would all the Israeli hostages. Most of the bodies were found riddled with multiple gunshots. The world had been waiting to see how Germany would protect these Jews.

Jim McKay of ABC News reported, “When I was a kid, my father used to say ‘Our greatest hopes and our worst fears are seldom realized.’ Our worst fears have been realized tonight. They’ve now said that there were eleven hostages. Two were killed in their rooms yesterday morning, nine were killed at the airport tonight. They’re all gone.”

They are all gone! Words like these shake your world. I was just a child at the time, but the “Munich Massacre” became part of my childhood, part of my vocabulary, part of who I am, part of our history as the Jewish people, as the people of Israel. We came as athletes, we came in peace, and the world failed us again. Back home in Israel we were all stunned, shell shocked, devastated. The wound was deep.

Five terrorists were killed during the botched rescue attempt and one German police officer was killed by the terrorists. The remaining terrorists, with only one exception, and many other leading terrorists who were involved in the planning of the massacre, were eventually tracked down by the Israelis and eliminated. One reporter wrote that the Israeli revenge operations continued for more than twenty years. He detailed the assassination in Paris in 1992 of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s head of intelligence and said that an Israeli general confirmed there was a link back to Munich.

The Olympic Games continued, but the Israeli team went home. The bravery and heroism of the Israeli athletes would not be forgotten. Yet, forty years later, despite pressure and fervent requests, the Olympic Committee refused to honor the dead with one single solitary minute of silence.

In a yeshiva in Jerusalem, once again Arab terrorists broke in with the intention of gunning down students. They broke through to the kitchen, but two of the boys blocked the door to the main dining room with their bodies, again, dying as heroes while allowing others to escape. They gave their lives to delay the terrorists long enough for the others to escape and for help to arrive.

So what was Professor Librescu at Virginia Tech thinking? What was going through his mind? He was living the lesson of Jewish history.

We will never know for sure what the professor was thinking, but I have a theory. I recall the story about the American Nazi’s planned march in Skokie, Illinois; home to many Holocaust survivors. When the leaders of the community spoke and advised people to “stay inside, lock the doors, close the shutters, don’t pay them any attention, don’t look,” a survivor rose up and said, “As I sat here listening to you I was reminded of a similar event, with similar speakers, men in suits who came from the big city to tell us what to do. But it was not in America, and it was a long time ago. It was when I was a boy in Germany, with my parents. The Nazis there too wanted to march, and the Jewish leaders there too urged restraint, ‘Don’t make trouble. Don’t give them attention.’ Those people were all killed. So don’t tell me to stay home, don’t tell me to be quiet, I will not listen this time, I will be out there with a baseball bat or a hammer, I will fight them with whatever I have, but I will no longer be silent. Never again.”

Professor Librescu was born in Romania. When Romania joined forces with Nazi Germany in World War Two, the young Librescu was interned in a labor camp, and then sent along with his family and thousands of other Jews to a central ghetto in the city of Focsani. Hundreds of thousands of Romanian Jews were killed by the collaborationist regime during the war.

Perhaps Professor Librescu remembered all those who were massacred back in his native Romania, perhaps he remembered killers like “the Butcher of Bucharest,” perhaps he learned that a nation of warriors fights back, that ordinary people do try to be heroes. The attack took place on “Holocaust Memorial Day,” and he gave the greatest memorial to the victims of those massacres and killings, he fought back.

The Yeshiva: Eight Holy Victims

As a young man, I was a student at the Mercaz HaRav rabbinical college, or yeshiva, in Jerusalem. This is an elite rabbinical institute, the crown of the religious Zionist academies, where young scholars study the Talmud and biblical texts. I recall my days there as days of purity; from morning until night our entire beings were immersed in holy pursuits. Our days were filled with the words of God, the prophets of old, ethical teachings of the rabbis, and lessons on how to conduct ourselves.

While I was in the United States in 2008 on a Krav Maga seminar tour, my rabbi called me with the terrible news; an Arab terrorist infiltrated the yeshiva and opened fire with an automatic weapon. He murdered eight holy students who were busily engaged in studying the word of God.

A nearby resident, David S., heard the shots. Like many, he was a young man home on leave from his basic military service. He grabbed his army issue rifle and without concern for his own safety ran to the scene of the slaughter. He chased the terrorist up to the roof where he shot him dead. Soon his brother-in-law would also have the opportunity to be the hero. One hero inspires another.

In 2008, while riding his bicycle down the main street of Jerusalem, Moshe P. notices a commotion. An Arab terrorist has come up with yet another original idea, he is driving his bulldozer into people on their lunch break, he is turning over cars, he runs his bulldozer into a commercial bus filled with people. The bus is overturned and several passengers are already dead as the ruthless terrorist continues to crush them with his bulldozer. Moshe leaps off this bike and runs toward the terrorist. He grabs a gun from a passerby, climbs on the tractor, and shoots and kills the terrorist. Several other passersby had also jumped on the tractor and wrestled with the terrorist before Moshe shot him. Later when interviewed, Moshe said, “I did what is expected of any civilian or soldier.”

Moshe was a member of the Golani brigade and was home on vacation. He was a resident of Jerusalem and a graduate of a yeshiva high school. Like many religious Israelis, he chose the challenging five-year hesder program, combining military service with religious studies.

After his heroic spontaneous action, Moshe received an award from General Eizenkot of the Northern command. The general said, “What is special in his actions is we are dealing here with a soldier at the start of his military path, who during a vacation happened upon an incident, displayed initiative, clear thinking and calmness, made contact with the enemy (a central teaching of Israeli military doctrine) and as such saved human lives. Sergeant P. set an example of how an IDF soldier should behave.” Present at the ceremony were friends and family, including his brother-in-law, David S., who killed the terrorist at the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva. The General added, “The same values came into play in both incidents and should serve as an example to all of us.”

Not three weeks later, another chance passerby had an opportunity to be a hero. Just before 2 pm, Ghassan Abu Tir, a twenty-two-year-old Jerusalem Arab, a construction worker working on a project near the King David Hotel in downtown Jerusalem, crashed his bulldozer into a local Jerusalem bus. He then continued to ram into five cars before he was shot dead by a driver. In this attack no civilians were killed, but several were injured and one lost a leg.

The terrorist succeeded in inflicting terror on the drivers. “I was driving on the main road when suddenly the tractor hit me in the rear on the right-hand side,” said Avi Levy, the bus driver. At first the bus driver thought it was a traffic accident, but the terrorist kept striking the bus again and again. Pandemonium broke out, passengers shouted, “God save us” and “escape, escape.” “He made a U-turn and rammed the windows twice with the shovel. The third time he aimed for my head—he came up to my window and death was staring me in the eyes. Fortunately, I was able to swerve to the right onto a small side street; otherwise I would have gone to meet my maker,” said Levy.

“There was panic on the street as people were running away from the bus,” said Yohanan Levine, an eye witness (Jerusalem Post, July 23, 2008).