The ideology of community lament set a snare from which neighborhood-effects research has never fully escaped. As a result, the decline of “community” has long been confused with the decline of place. But definitions of these concepts can be separated, and I start by teasing out the idea of neighborhoods in the physical or spatial sense rather than as a form of social solidarity. The broad definition of neighborhood that was provided by Park and Burgess was that of people and institutions occupying a spatially defined area that is conditioned by a set of ecological, cultural, and political forces.1 In a utopian-like way Park went so far as to claim that the neighborhood formed “a locality with sentiments, traditions, and a history of its own.”2 He also viewed the neighborhood as the basis of social and political organization.

Park’s definition overstated the political distinctiveness of residential enclaves, and the criticisms of the Chicago-School idea of the natural area are well known. Neighborhoods are not monolithic in character or composition, and market forces are not the only force behind the formation of community. Still, criticisms of the natural area concept may have themselves been overstated. As Gerald Suttles reads Park and Burgess rather than their caricature, “they meant to emphasize the ways in which urban residential groups are not the planned or artificial contrivance of anyone but develop out of many independent personal decisions based on moral, political, ecological, and economic considerations.”3 In the current era it is reasonable to think this describes many if not the majority of neighborhoods, even allowing for important nonnatural processes or constraints. The problem with the political economy or any purely structural critique is that it brackets individual choice and assumes more unified macrolevel control over individual behavior than seems warranted. Pure “top-down” thinking is not better than pure “bottom up.”

Hence there are some aspects to Park’s reasoning worth preserving. One is the recognition that neighborhoods are spatial units with variable organizational features, and the second is that neighborhoods are nested within successively larger communities. Neighborhoods vary in size and complexity depending on the social phenomenon under study and the ecological structure of the larger community. This notion of embeddedness is why Choldin emphasized the fact that the local neighborhood is integrally linked to, and dependent on, a larger whole.4 For these reasons, I prefer to think of residential neighborhoods as having a “mosaic of overlapping boundaries” emphasized by Suttles, or what Reiss called an “imbricated” structure.5

The socially constructed nature of the local community is another essential idea that postdates the Park-Burgess model. Suttles identifies what might be thought of as a cultural mechanism (which I will return to in the chapters to follow) when he posits that “residential groups are defined in contradistinction to one another.”6 It is the nature of community that it matters differentially, and so residents sort themselves and identify themselves with broad groupings, especially along race, ethnic, and class lines. It is for this reason that neighborhoods are still salient in the contemporary city: they are markers for one’s station in life and are frequently invoked for this purpose. This does not mean neighborhoods are homogenous, only that they gain their identity through an ongoing commentary between themselves and outsiders, a collective version of the “looking-glass self.” Community identities are both positive (Gold Coast, Upper East Side, Happy Valley) and pejorative (Jew Town, Back of the Yards, Skid Row), underscoring the collective determination of the symbolic nature of community and its physical boundaries.7 In this sense neighborhoods and larger residential communities often take on a distinct sense of place that embodies a set of meanings that go well beyond physical location.8 This pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that the cultural principle of difference is layered onto the ecological landscape. The broader inference we can draw, initially, is that one of the mechanisms of enduring spatial inequality in the United States is “ho-mophily,” or the tendency of people to interact, associate, and live near others like themselves and to maintain distance from those disvalued.9 One might think of this as the demand side of inequality—leading to what we can think of as a spatial form of hierarchy maintenance, a mechanism I explore in later chapters. Actions taken by individuals and institutions to maintain privileged positions produce the sorts of structural constraints typically emphasized by sociologists. But cultural principles of identity are also at work in the selection of places that inscribe social distance into neighborhood difference.

An extension of the social construction of community is the “defended neighborhood.” According to Suttles, the defended neighborhood arises from a perceived threat of invasion from outside forces.10 As such, defended neighborhoods can only be understood in relational terms. One of the paradoxes of community cohesion is that it is often generated by external threat, a point recognized by Coleman fifty years ago in his defense of a macrolevel conception of social disorganization.11 Racial turnover is the classic case that comes to mind, but perhaps political threats may be equally important, for example when Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley announced in 1990 that he planned to build a new airport in the southeastern community of Hegewisch. Under siege and faced with physical destruction, Hegewisch became the quintessential defended neighborhood, mobilizing to defeat city hall and developers with many millions of dollars at stake. In this case a latent sense of community was ignited and reinvigorated by an external threat, leading residents to defend their common interests.

We are confronted, then, with a complex social phenomenon. Neighborhoods are both chosen and allocated; defined by outsiders and insiders alike, often in contradistinction to each other; they are both symbolically and structurally determined; large and small; overlapping or blurred in perceptual boundaries; relational; and ever changing in composition. Suttles’s concept of the defended neighborhood also unveils the potential interaction between boundaries and socially constructed meaning—ecological boundaries can be perceived as either sacrosanct or meaningless, and therefore must ultimately be socially understood. Moreover, apropos of the “community liberated” argument, social networks are potentially boundless in physical space. This characteristic of social networks allows groups to share identity and exist anywhere—they may or may not be spatially bounded by neighborhoods. It therefore can be seen that neighborhood invokes two meanings in the literature—physical proximity or distance (as in “neighbor”) and variable social interaction, usually considered in face-to-face terms.

These conceptual conundrums are often glossed over in the futile search for a single operational or statistical definition of neighborhood. I begin instead by conceptualizing neighborhood in theoretical terms as a geographic section of a larger community or region (e.g., city) that usually contains residents or institutions and has socially distinctive characteristics. This definition highlights the general characteristic of neighborhoods from ancient cities to the present—they are analytic units with simultaneous social and spatial significance.12 An empirical test is implied that the review in chapter 2 of various operational definitions rejected—if there is no ecological differentiation (or clustering) by social characteristics, there is no neighborhood in the socially meaningful sense. But as we have seen, there is considerable neighborhood social inequality or differentiation, and more will be shown. My conceptualization also views neighborhoods as nested within larger districts or local communities that are recognized and named by institutional actors and administrative agencies.13 In many cases both residents and institutions identify neighborhoods and local communities interchangeably— for example, Hyde Park in Chicago is considered by most of its residents and by the University of Chicago as a neighborhood, but it is also rather large (about thirty thousand residents) and simultaneously considered a local community.

These analytic moves avoid conflating neighborhood and local community with the existence of strong face-to-face intimate, affective relations that are thought to characterize primary groups.14 Such a primary-group assumption probably always has been false. Henry Zor-baugh, a contemporary to Louis Wirth, wisecracked back in the 1920s: “Along the Gold Coast, as elsewhere in the city, one does not know one’s neighbors.”15 But this did not imply then the analytic irrelevance of how spatial proximity interacted with social distance or the social sorting of groups into different neighborhoods. Nor does it now, and even in today’s more interconnected world it remains the case that some neighborhoods are tight knit and characterized by frequent social interaction. Neighborhoods are conditioned by a varying set of ecological, sociodemographic, institutional, cultural, and political forces, as are many other subjects of social inquiry. How family is defined is the subject of considerable contention, for example, but this does not mean that family is a social construct void of causal power.16 The political borders of societies are also variable, and many people within those borders do not maintain a national identity. But as Rogers Brubaker argues, nationalism is a legitimate object of scientific inquiry that is rooted in everyday practices and institutionalized forms, even if “nation” is a socially contingent concept.17 Groups do not lack causal power because their boundaries are socially constructed or they lack internal cohesion.

The logical implication of my approach is that sometimes neighborhoods make a community in the classical sense of shared values, solidarity, and tight-knit bonds, but often they do not. What some might call “neighborhoodness” (e.g., dense social interactions, place identity, or exertion of social control) is a contingent or variable event. The extent of structural or cultural organization (and for what) is an empirical question, leaving the extent of solidarity or social interaction within (and across) neighborhoods as subjects for investigation.18 It is the intersection of practices and perceptions in a spatial context that is at the root of neighborhood effects. When formulated this way, social factors—whether network ties, shared perceptions of disorder, organizational density, cultural identity, or the civic capacity for collective action—are variable and analytically separable not only from potential structural antecedents (e.g., economic status, segregation, housing stability) and possible consequences (e.g., crime, wellbeing), but from the definition of the units of analysis. This conceptualization allows empirical research to proceed without tautology and, as we shall see, offers a scalable menu of options for measuring theoretical constructs across ecological units of analysis.19

Out of the Ghetto

What we might call the “poverty paradigm” has dominated the urban research agenda at least since Wilson’s classic, The Truly Disadvantaged.20 Concepts such as the “inner city,” “underclass,” and “ghetto” have dominated intellectual debate. While important, poverty is a relational concept that requires an understanding of the middle and upper echelons of society. “Inner-city” poverty is also no longer valid ecologically—many of the poorest neighborhoods are in the far flung corners of U.S. cities or the suburbs, and Chicago is no exception, as we shall see. Yet the poverty paradigm has directed many surveys to focus solely on poor individuals, and the majority of ethnographies are on poor communities. Recent decades have seen an outpouring of excellent urban ethnographies, but virtually all of them are located in black or poor ethnic communities.21 That much of urban sociology has focused on the lives of the poor and downtrodden is quite striking in its implications—neighborhood variation across the full range of structural contexts and social mechanisms remains a limited topic of inquiry.

In this book I thus move beyond the confines of the “ghetto” and focus on social mechanisms theoretically at work across a broad spectrum of factors such as informal control, network exchange, homophily, selection, and organizational capacity. As introduced in the last chapter, I conceptualize a social mechanism as a plausible contextual process that accounts for a given phenomenon, taking as its central goal the empirical study of the sources and consequences of social behaviors that vary across neighborhoods. It follows that I take a comparative approach, investigating multiple neighborhoods over time, whenever possible. This strategy counterbalances the tendency in some of the ethnographic literature to make comparative claims based on single cases and in some of the quantitative literature to focus on cross-sectional or one-shot studies. Starting with William F. Whyte, for example, a common refrain by critics of social disorganization theory is that they see evidence of organization in the neighborhoods they are studying. Most recently, Martin Sanchez-Jankowski writes in this tradition, saying that in his long stays in high-poverty neighborhoods he “only once experienced (and only briefly) social disorganization.”22 Setting aside how different observers might define (dis)organization or whether they would see the same thing in the same neighborhood, the issue is not some absolute level of social organization but rather its variation across communities and time. Sanchez-Jankowski might thus be right, but we would need to know the level of organization in other neighborhoods (say, upper or middle income as opposed to only poor) and how they also changed in order to make claims about neighborhood-level theories of social organization.23 The advantage of a comparative framework, which in principle can be ethnographic or not, is the ability to directly make such comparisons.24

A focus on comparative social mechanisms should not be read to imply a neglect of cultural and symbolic processes or a search for universal covering laws. The approach of this book and its study design allow me to simultaneously probe what may be the most powerful role for neighborhoods in the contemporary city—perceptual (or cognitive) social organization. Neighborhood studies have often been conceptualized in terms of objective structural variables that could be implanted anywhere. When social organizational factors, such as networks and control, are studied directly, they are also often considered to be analytically separate or independent from the perceptions and interpretations that give them meaning. But as Gerald Suttles and Albert Hunter, and Walter Firey before them, have shown, places have symbolic as well as use value.25 Places are also interpreted and narrated—“imagined”26 —and these symbolic gestures in turn reinforce the idea of place. Tom Gieryn has argued that places are not just abstract representations on a geometric plane; they take on social significance through the interaction of material form, geography, and inscribed meaning.27 When Mayor Daley II moved out of Bridgeport and “up” north, it was cause for widespread handwringing in Chicago not just because of either the place’s race or working-class composition, but because of what the move stood for symbolically and politically—a concession to the “Lake Side Liberals.” Many other neighborhoods in Chicago convey a distinct stereotype, just as in other cities. Beacon Hill, the Tenderloin, Hollywood, Bed-Stuy, Kensington, and the Left Bank, to name a few, convey a distinctive meaning and sense of place. Neighborhoods have reputations that may well be sturdier than individuals.

In short, people act as if neighborhoods matter, which is a fact of profound importance in the social reproduction of inequality by place. Consideration of both the cultural and structural mechanisms that make neighborhoods meaningful is a central task of this book.

Ecometrics

What has hindered the analysis of social processes and mechanisms? Theory plays a role because theory guides the production of methodological tools and analytic approaches. Here is where sociology stumbled in the “decontextualization” phase of the mid-twentieth century, when the Chicago-style tradition of research was slowly overtaken by the increasing dominance of individual-centered questions and survey research.28 The focus in sociology turned narrowly to individuals, both as units of data collection and targets of theoretical inference. Although this dominance has been challenged, especially by ethnographers, it persists despite the resurgence of interest in neighborhood effects. Not only does most research continue to focus largely on the ghetto poor and negative outcomes at the traditional bottom of the heap, quantitative research in particular usually treats social context as just one more characteristic of the individual used to predict individual variations.

By contrast, I argue that we need to treat social context as an important unit of analysis in its own right. This calls for new measurement strategies as well as a theoretical framework that do not treat the neighborhood simply as a “trait” of the individual. However, unlike individual-level measurements, which are backed up by decades of psychometric research into their statistical properties, the methodology needed to evaluate neighborhood properties is not widespread. For this reason Stephen Raudenbush and I proposed moving toward a science of ecological assessment, which we called “ecometrics,” by developing systematic procedures for measuring neighborhood mechanisms, and by integrating and adapting tools from the field of psychometrics to improve the quality of neighborhood-level measures.29 Setting aside statistical details, the important theoretical point is that neighborhood, ecological, and other collective phenomena demand their own measurement since they are not stand-ins for individual-level traits. I believe this distinction is crucial for the advancement of theoretically motivated neighborhood research. Underlying this book’s conceptual emphasis on neighborhood social processes is therefore a simultaneous quest for the development of methodological tools that serve theoretical goals—a metric for the social-ecological contexts of the city.

“Extralocal” Processes and the Larger Social Order

The idea of ecometrics leads naturally to another challenge—that of linking neighborhoods and places together in the larger social order of the city. Prior research on neighborhood effects has focused largely on the idea of “contained” or internal characteristics, assuming that neighborhoods are islands unto themselves. This approach is surprising given that a workhorse of urban ecological thinking is spatial interdependence. Recently have we seen advances in spatial techniques that I capitalize on, allowing me to capture the interdependence of social processes through spatial networks, and thereby mechanisms such as diffusion and exposure.

It remains true, however, that previous approaches have largely limited their focus to how internal neighborhood characteristics are associated with the internal characteristics of a “neighborhood’s neighbors”— spatial proximity or geographic distance has been the defining metric for the recent advances in spatial social science. While important, the ways in which neighborhood networks are themselves tied into the larger social structure of the city in nonspatial ways are not well understood and rarely studied. Ironically, the classic work of Robert Park and Ernest Burgess envisioned research on the ecological structure where neighborhoods only were pieces of the mosaic of the city.30 The political economy critique made a similar point as did the social network theorists: nonspatial relationships are just as important theoretically as internal neighborhood characteristics and therefore studies of place cannot proceed by considering their indigenous qualities only. It is not just city-level processes that are at stake—national and global forces can influence place stratification. As Wilson argued in The Truly Disadvantaged, deindustrialization and the shift to a service economy was disproportionately felt in the inner city.31

How do we go about documenting the extralocal layers of these kinds of macrolevel influences? What might be the biggest hurdle to neighborhood-effects research is the simple fact that neighborhoods are themselves penetrated by multiple external forces and contexts. Acknowledging this and studying it are two different things—critiques of the Chicago School are legion but convincing empirical demonstrations of the effects of “larger” structures are thin. Motivated by this concern, I explore in this book the implications of thinking in terms of interconnected and multilevel social processes that go beyond the idea of an isolated urban neighborhood. My strategy is to examine how residential mobility, organizational ties, and elite social networks differentially connect neighborhoods to the cross-cutting institutions and resources that organize much of contemporary economic, political, and social life.32 This strategy is pursued through analysis of moving trajectories across neighborhoods and in the Key Informant Network Study, a panel study of the networks among leaders, organizations, and ultimately neighborhoods of Chicago. These data permit me to address one of the most basic but untested propositions in the literature, in which the unit of analysis is relations between and across neighborhoods—not merely as a function of geographical distance (e.g., ties in adjacent neighborhoods) but of the actual networks that cross-cut neighborhood and metropolitan boundaries. For example, I examine the network structure of the citywide pattern of residential migration and informational exchange among leaders. I also examine how the structural pattern of ties among key community actors is related to variation in organizational and social resources.

A caveat is nonetheless in order. My project is not one that attempts to reveal the full workings of the global economy or other macropolitical forces on neighborhood effects. This is not to say global or “State” effects are unimportant, only that it is not possible with my research design to do them justice in their own right analytically. But I do claim that macrolevel processes are lived locally and experienced on the ground in everyday life, a claim that perhaps ironically has its roots in the non-quantitative method of ethnography. The implication for strategy is that I attempt to connect multiple scales of influence wherever possible. Especially in part 4, this multitiered approach attempts to lay bare the connections to and from larger-scale political, network, economic, and organizational processes that operate beyond local boundaries but that have implications for community and individual life. Such higher-order links among communities constitute a different kind of neighborhood effect that is rarely considered, one that forms a key analytic goal of this book.

Individual Selection Reconsidered

The reader at this point may suspect I am a structural determinist. But this study should be read as saying that individuals matter too. How neighborhoods change and how city dynamics are brought about are considered not just from the structural view or from the “top down” but also from the “bottom up.” In Foundations of Social Theory James Coleman presented a heuristic that illustrated the different analytic links in studying micro and macro processes that connect the “top” and individuals at the “bottom.” Although I do not accept or apply his underlying rational choice framework and I reject the rigid strictures of “methodological individualism,” I believe it is productive to consider Coleman’s analytic scheme for understanding micro and macro links and apply it to our present concern with neighborhood effects to see how far it can take us.

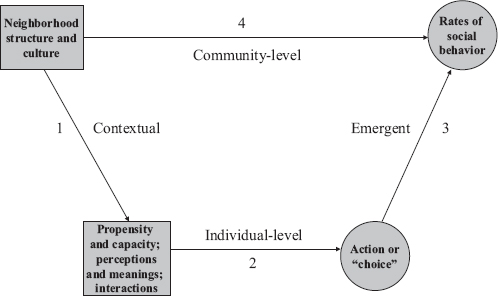

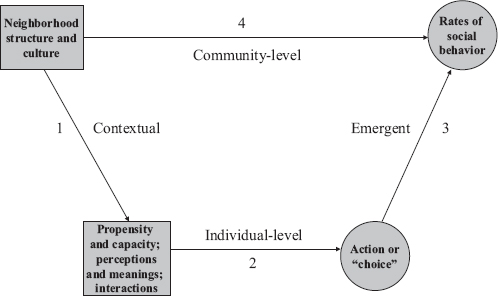

FIGURE 3.1. Conceptual model of neighborhood micro-macro links

In figure 3.1 I graph across the top the macrolevel connections emphasized in chapter 2, what I call “side-to-side” analysis (e.g., between-neighborhood associations of concentrated poverty with crime rates). These are also represented as the link-4 connections. Link 1 reflects “contextual effects,” in this case of neighborhoods, on individuals (“top down”), especially on their propensities and capacities and the kinds of social interactions and meanings that influence behavior—“action” in the Coleman sense.33 Most social science operates at the individual-level link 2, whereas research in the Chicago School tradition tends to operate either at the “macro level,” theorizing connections “side to side” across the top of the Coleman “boat” (link 4), or at the contextual level of link 1. The task of this book is to better understand the mechanisms that connect the entire process through the various multilevel links, including side-to-side or community-level links and both bottom-up and top-down links. My task is also to better define and study the role of context, what I consider the main failure of methodological individualism.

This strategy leads me to a reconsideration of the common wisdom regarding the role of individuals and the current popularity of experiments. In chapter 2, “selection bias” due to individual sorting was a ubiquitous concern in the literature on neighborhood effects.34 There is widespread concern that because individuals make choices and sort themselves by place, nonrandomly, estimates of neighborhood effects on social outcomes (most commonly crime, teenage childbearing, employment, mortality, birth weight, social disorder, and children’s cognitive development) are therefore confounded. By and large the response to this critique has been to take selection as a statistical problem to be controlled away rather than as something of substantive interest. As chapter 2 revealed, the usual method in neighborhood-effects research using observational data is to control away many individual-level variables. A more recent approach has been to conduct experiments in order to obtain more unbiased causal inferences.

James Heckman has recently articulated what he calls the “scientific model of causality,” in which the goal is to confront directly and achieve a basic understanding of the social processes that select individuals into causal “treatments” of interest.35 Although I do not adopt a formal model or economic theory and while I do not adhere to an overly “scientistic” stance, I do think that studying the individual sorting and selection into neighborhoods of varying types is an essential ingredient in my larger theoretical project of understanding neighborhood effects. Relying on randomization through the experimental paradigm sets aside the study of how these mechanisms are constituted in a social world defined by the interplay of structure and purposeful choice. In this book I therefore focus on a key aspect of selection—neighborhood location or choice—and treat the neighborhood outcome achieved by the individual as problematic in its own right. This approach allows me to examine the sources and consequences of sorting for the reproduction of social inequality in the lives of individuals, and for the reproduction of the stratified urban landscape (links 1 and 2 in fig. 3.1). Equally important, by taking selection and the micro to macro link 3 seriously, rather than defining it away, leads me to study how individual choices in the form of residential movement leads to “upward” consequences that ramify across the city and beyond (and, in turn, back to link 4). These are connections that define the demography of the wider city. Individual actions are constitutive of the bird’s-eye view, in other words.

FIGURE 3.2. Dynamic residential mobility flows, 1995–2002

To use a simple example and motivate the idea of the interconnected city, consider that if I move from community A to B I engage in an individual action but at the same time I establish a connection or exchange between these two places. Structural consequences ensue. In figure 3.2 each line represents a connection created by a move between an origin and destination neighborhood of families within the Chicago study soon to be described in detail. Neighborhoods are denoted by circles, and the thickness of lines is proportional to volume of flows between neighborhoods. One can see that the individual moves create an emergent social structure of “exchange” among neighborhoods. Some flows reflect white flight, others the increasing diversity of formerly black areas, and still others moves to the suburbs. I explore in Chapters 11–13 how these and other types of “micro” actions yield social structural connections between neighborhoods of different racial, economic, and social makeup, helping us to better understand the reproduction of persistent urban inequality. In chapter 14 I examine individual and cross-neighborhood connections of a different sort—key informant networks—and how they constitute Chicago’s social structure.

Unlike many research efforts on neighborhood effects that privilege a hierarchically nested or top-down effect of neighborhoods on the individual, I thus consider side-to-side, bottom-up, and bird’s-eye orientations along with issues of ecometric measurement, social causality, extralocal spatial processes, perceptions as causation, and selection bias all as a way to address the scheme in figure 3.1. I also firmly believe that macrolevel mechanisms (link 4) have their own social logic and are not reducible to individual actors in the ways that methodological individualists imply.36 My argument is thus that there are many ways to conceive of neighborhood effects, with the dominant top-down pathway important but far from the only link worth considering. Even when contextual link 1 is at issue, its conceptualization is typically narrow, and mediating pathways from neighborhood context are inappropriately controlled away, as in the ubiquitous notion of attempting to render “all else equal.” If neighborhood conditions are implicated in cognitive perceptions and evaluations, for example, they are causally implicated in individual behavior and social structure alike. Although social life may be said to be emergent, its structure is produced by a complex set of relations among individuals that are shaped by macrolevel and often durable neighborhood processes.37 My analytic approach therefore moves back and forth between the various “levels” of the social structure of the contemporary city, with an eye to explaining and integrating the multiple causal processes that reflect a broad conception of neighborhood effects.

Theoretical Principles

Backed by over a decade’s worth of original data collection from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, my goal is to place contextual processes on a theoretical foundation that recognizes the ways in which metropolitan life has been transformed over the years. As noted, what unites all the chapters is a concern with the social mechanisms and dynamic processes of place in the contemporary city—in this case, Chicago. The Chicago School of urban sociology that nourished me as a scholar provides a grand tradition for such work, but it must also be reinvented—just as Chicago the city is currently being reinvented.

I propose ten active elements of what I view as a general theoretical approach to the study of neighborhood effects and the contemporary American city.38 I refer here not to specific hypotheses that will come later, but to the larger or more abstract principles of Chicago School–inspired social inquiry that are operationalized and expanded upon in this book:

1. Relentlessly focus first and foremost on social context, especially as manifested in urban inequalities and neighborhood differentiation.

2. Study neighborhood-level or contextual variations in their own right, adopting an eclectic style of data collection that relies on multiple methods but that always connects to some form of empirical assessment of social-ecological properties, accompanied by systematic standards for validation—ecometrics.

3. Across ecological contexts and guided by ecometric principles, focus on social-interactional, social-psychological, organizational, and cultural mechanisms of city life rather than just individual attributes or traditional compositional features like racial makeup and poverty.

4. Within this framework, integrate a life-course focus on the temporal dynamics of neighborhood change and the explanation of neighborhood trajectories.

5. Invoke a simultaneous concern for processes and mechanisms that explain stability, highlighting forms of neighborhood social reproduction.

6. Embed in the study of neighborhood dynamics the role of individual selection decisions that in turn yield consequences for neighborhood outcomes—treat selection as a social process, not a statistical nuisance.

7. Go beyond the local. Study neighborhood effects and mechanisms that cross or spill over local boundaries to yield larger spatial (dis) advantages.

8. Go further still and incorporate macro processes beyond the influences of spatial proximity, building a concern with the social organization of the city or metropolitan area as a whole, integrating variations across constituent neighborhoods with higher-order—or nonspatial—networks that connect them.

9. Never lose sight of human concerns with public affairs and the improvement of city and community life—draw implications for community-level interventions as a scientifically principled alternative to the individual disease model of medicine.

10. Finally, emphasize the integrative theme of theoretically interpretive empirical research while taking a pluralistic stance on the nature of evidence and causation. The disjuncture that often exists between theory and empirical research, akin to the so-called two cultures problem39 of quantitative versus qualitative, seems never to have had much force at Chicago. It should not today.

These ten principles entail a number of modi operandi that I build or infer from the Chicago School and adapt to the contemporary social world. In essence I argue that the activities if not the thoughts of the Chicago School yielded agreement on a “contextualist paradigm,” premised on the notion that “no social fact makes any sense abstracted from its context in social (and often geographic) space and social time.”40 This is a robust approach to social life that links theory to operational concepts to make sense of the empirical world of the ever-changing city (not other theorists). My approach thus attempts to unite method and theoretical principle, viewing theory in its classic form—the analysis of a set of empirical facts in their relation to one another, organized by a set of guiding explanatory principles and hypotheses. The specific theoretical claims and hypotheses are laid out in the individual chapters that follow.

A Note on Style

As the next chapter will reveal, the PHDCN is a large effort that has evolved in multiple directions. Its tentacles are to be found in many places, and future investigators will undoubtedly take the project in other directions not yet known.41 But at present almost fifteen years’ worth of research and publications now need to be brought together in one place and synthesized. There are also many new results to report and previously unanalyzed data sources that I tap. While I do not attempt to cover all prior material produced from PHDCN, one learns from cumulative experience, including both its progress and mistakes. The challenge is that the published articles on PHDCN so far are like unassembled pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, scattered in many different places and written with different voices. Given the public nature of much of the project and its eventual data, I thus consider it incumbent on me to assemble these diverse pieces and describe in an integrative way and in one voice how past work set the stage for the framing of my subsequent empirical work. Against this backdrop I then present new data and findings accompanied with a synthetic and revised portrait of the overarching theoretical framework.

In particular, I focus in this book on dynamic processes and longitudinal data collected in the PHDCN follow-ups at both the individual and the neighborhood and community levels, in addition to cognate panel studies of other-regarding behavior, collective civic engagement, organizations, and elite networks. I also rely on personal interviews with community leaders and field observations I recorded over the course of the study in strategically chosen neighborhoods. The result is that virtually all of the empirical findings and observations that I highlight, especially in figures, reflect original analysis. The remainder reinterprets prior results from a longer-term perspective, with each chapter dipping into topics, data sources, or analyses not previously explored. This integrative strategy requires me to revisit prior findings and places, interrogate them with longitudinal data, and then revise them again, culminating in a set of final field visits and data collection strategies conducted in Chicago in 2010. These revisits engage not just with PHDCN-related material but entail a dialogue with an ongoing stream of studies that were conducted in Chicago over the last century and that have enriched social science.42

The study of neighborhood effects and urban social structure is complicated and raises a hornet’s nest of methodological challenges. It is thus not surprising that a great deal of technical material has been produced from the PHDCN. The challenges are not minor, and I have spent years with my colleagues trying to solve one or another empirical problem. The details behind much of this groundwork can be found in peer-reviewed journals, supplemental materials, and footnotes to this book, but I will keep the focus here on painting the big picture. As a result this book is largely “coefficient free” and nontechnical. In fact there are no tables. At the same time, data are important to see and I do not believe readers should simply trust authors. Herein lies the dilemma of presenting scholarly and at times densely researched findings in an accessible way. My solution in this book is include for the reader a large number of maps and figures that are meant to portray visually the theoretical ideas and empirical regularities that have been vetted back and forth with more complicated methods. I believe this strategy is warranted by the scope of the inquiry and hope the journey is worth any challenges to the reader. Those who wish to retrace my steps, pore over evermore details, or dig deeper into method may do so by following the roadmap provided in the footnotes, online sources, and citations.43