In the summer of 2010 I returned to the streets of Chicago that I had walked many times over the years and that were introduced to the reader in chapter 1. Retracing my steps provides a chance to reflect on the empirical findings and general ideas that I synthesized in the previous chapter while grounding them in a context that is propitious for analytical leverage. The fall of 2008, as we now know all too well, saw a calamitous economic crisis that began in the U.S., but that rippled outward. The economic shock hit American cities after a prolonged boom and shattered the confidence of elites and lay people alike—in 2009, poverty rose to its highest level in fifteen years. Like a hurricane or heat wave, an economic crisis provides the analyst with an opportunity to examine how social structure deflects or exacerbates “disaster,” in this case one that is decidedly unnatural in causal origin.1 The large-scale transformation of public housing in Chicago adds another layer of human intervention—here, by the government—that dislocated tens of thousands of families. Chicago has changed in many other ways both large and small, including that, for the first time in twenty-two years, Richard M. Daley is no longer Chicago’s mayor.2

My aim, then, is to close out the theoretical arguments of the book against the backdrop of recent social change. Returning to the logic of where I began in chapter 1, I take both a street-level and bird’s-eye view of the city, situating in specific places, and at the higher-order or structural level, the continuing salience of neighborhood differentiation. This strategy provides a contextualized portrayal of Chicago neighborhoods fifteen years after the PHDCN was launched, while at the same time affording an overall glimpse of how the city has absorbed a global economic crisis and public housing transformation on a massive scale. Motivated by the book’s comparative strategy and key findings, I highlight how the linked processes of stability and change have played out across multiple neighborhoods. Of special theoretical interest are communities that have gone against the grain and bucked the trend predicted by their prior histories or that are confronting external challenges in notable ways. For example, what is it about communities that fall on the “off-diagonal” or are otherwise anomalous in their response to the economic crisis, or that have stepped up to increases in crime against great odds? This book has also provided unmistakable evidence on mechanisms of neighborhood social reproduction. Is durable inequality still maintained, and in what ways?

My empirical sources are multifaceted in nature and include personal field observations, housing foreclosures filed during and after the economic collapse, incidents of violence in 2010, newspaper accounts and local reporting, administrative records on the location of public housing and voucher users after the demolition of CHA projects, and a smaller-scale replication of the letter-drop study in a strategically chosen sample of neighborhoods that I conducted in June of 2010. These data, qualitative and quantitative in form, are woven together to paint a final holistic picture of the social organization and deep structure that still defines Chicago.

Seeing Change

It was a warm June day, but the feel was much like my visit to the Magnificent Mile on a cold day in March of 2007 and countless times before that. Cartier, Van Cleef and Arpels, and Tiffany & Co. were sparkling. At Erie and Michigan I noted cranes in action, with apartments being advertised “starting at 1.4 million” (presumably studios on the lower floors) before completion was anywhere in sight. It was hard to tell that a severe recession was in high gear, although upper-end stores expressed their response to hard times in amusing ways: a man stood on Michigan with a huge cardboard tent sign draped over him, advertising Gucci, Armani, Prada, and Dior—“now 10% off.” People seemed to take notice. But North Michigan Avenue looked as busy as ever and little worse for the wear of the global downturn.

FIGURE 16.1. Old meets new Chicago: Donald Trump Towers over the classic Wrigley Building. Photograph by the author, June 12, 2010.

At the Chicago River, Donald Trump’s skyscraper is complete and towers high over its neighbors, notably the classic Wrigley Building just to its east. Built in the 1920s, the Wrigley is considered one of America’s most famous and beautiful office towers. The juxtaposition of old and new is jarring, but it symbolizes Chicago’s simultaneous interplay of stability and change. The photo I took on this June day (fig. 16.1) captures this surreal pairing. As on previous visits when the building was going up, tourists are snapping pictures of the tower and the impressive array of buildings along the Chicago River. Near the Wabash Street entrance, a security man paces outside, keeping an eye on things. Even he looks true to the Trump image of privileged sleekness, well dressed and with the latest in electronic communications dangling from his head. Busyness, importance, and wealth are projected all around Trump’s entrance.

After I cross the Chicago River into the Loop, Millennium Park continues to exude the theme of bold and new against a classic backdrop. And it is still drawing crowds. I have to admit that the controversial extravaganza is impressive, and the project does work as a testament to Chicago’s audacious ambition and architectural dominance. From Louis Sullivan to Frank Gehry seems almost natural. On this day anyway, Gehry’s pavilion reflects the sun and blends in well with the environment. As in the winter, people mill about and the projected faces of average citizens stare out of the fountain’s facade alongside Michigan Avenue. The only difference is that instead of skaters gliding about, kids splash in the water. Looking east and continuing through the South Loop and past Roosevelt Road into the Near South Side, one sees additional evidence of the gentrification that has reclaimed the old rail yards and single-room-occupancy hotels. New condominiums are scattered throughout the area, especially in the new “Eastside” (east Loop) and along South Michigan Avenue between 13th and 18th streets.

Further down Michigan Avenue, beginning at around 35th Street, the transformation of the Near to Mid South Side is ongoing. Many high-rise and low-rise housing projects are gone, and mixed-income housing is present where once only concentrated poverty reigned. I see evidence of several new apartment buildings just off South Michigan that I did not recall from less than a year earlier. But as before, there is an absence of vibrant street activity and it is not hard to find trash in the street or vacant and boarded-up buildings as you move slightly west or east. Even directly on South Michigan, around Pershing Boulevard, one sees abandoned lots and apartments with plywood covering the windows, often next to an occupied unit. Mary Pattillo reports that Grand Boulevard (or Bronzeville) is ambivalent about redevelopment, and the physical landscape almost seems to reflect this attitude.3 Consistent with this view, there is an odd mixture of vacant lots from the former housing projects sitting cheek by jowl with new condominiums and evidence of a thriving black middle class. I noted multiple boarded-up buildings on 47th Street in March 2007 and saw a group of homeless men sitting around a fire on a trash-strewn lot at Drexel and 43rd and near 47th. Over three years later I cannot say that the feel is much different. The homeless men are not at the same location, but I see smaller groups of men, apparently homeless, in other nearby places. The lot is still empty and 47th Street remains pocked with physical signs of disrepair. The recession seems to have slowed progress, as many buildings along major thoroughfares are empty and appear victims of increased home foreclosures.

Although still in transition, the neighborhoods in Oakland and most of Grand Boulevard nonetheless represent a distinct turning point in the history of Chicago’s poor. The major intervention on the part of the city did not have miraculous results, but it did substantially alter the community’s trajectory, for better or worse. Change is most pronounced around the areas where the projects once stood. Considering the legacies of inequality I have demonstrated, this is no small feat. But legacies usually do not simply vanish; they linger on and are constantly negotiated. And some challenges were simply passed on to other communities—even if the poor move elsewhere, they are still present. Social service demands must thus always be considered in a larger metropolitan context and cannot be limited to one neighborhood. The south suburbs are already feeling the impact of the city’s changes.

Back on South Federal Street, things look today almost exactly like they did in Figure 1.1, around the former site of the Robert Taylor Homes. I go to the same spot and find it as before, empty and quiet—dead space, as it were. The only difference is that a Chicago Police officer sits in a cruiser parked about a hundred yards away in what was formerly a street teeming with people. He eyes me carefully as I stroll around. Other than the officer there is no one within sight of me for what seems like a long time. Clearly mine is not an everyday activity, although a green expanse of grass stretches out before me. The space is marked by a strong history, and its stigma apparently lingers on. If the results of this book are any guide, it will be some time before social transformation is complete, if it ever is.

Further south and east, the community of Hyde Park looms large, home to the University of Chicago and the president of the United States.4 Hyde Park has been stable after its brush with rapid change in the mid-twentieth century and maintains its integrated housing with a mix of organizational and structural advantages. The most obvious is the university, but the community boasts a robust civic life, a density of nonprofit organizations, an educated elite, and connections to power. I looked up the most recent data available I could locate (2005) on the density of nonprofit organizations, using the same sources used in chapter 8. Of all the communities in the city of Chicago, Hyde Park ranked sixth or in the top 10 percent. Its rate of collective civic action events in 2000 (also see chapter 8) was fifth in the city. Using the Key Informant network data from chapter 14, it comes out on top in terms of the density of direct and indirect ties among leaders. These external indicators correspond to the qualitative feel one gets walking in Hyde Park and talking to its residents and leaders, and it comports with my local knowledge of the place gleaned over twelve years. As noted in chapter 1, community input and institutional connections are manifested in visible cues (e.g., signs, churches, bookstores, petitions) and a density of community organizations. Obama’s presence has only solidified the organizational identity of the community, both internally and nationally.

Just west of Hyde Park, however, stark differences (again) remain. Across Washington Park the community of the same name has seen attempts at recovery but is still waiting for jobs and economic rebound. Along the major thoroughfare of Garfield Boulevard and spilling into its side streets, vacant and boarded-up buildings, gated stores, and empty lots are not uncommon. As noted in chapter 1, if Kenwood and the gentrification near the lake in Grand Boulevard approach the status of a “Black Gold Coast,” then Washington Park and the lingering memories of the areas around the old Robert Taylor Homes may constitute the nearby “slum,” as perceived by many Chicagoans. Mayor Daley made a visible point of trying to invest in this area in the form of proposed new construction for the 2016 Olympics, but Chicago failed in its bid. On any given day, many of Washington Park’s struggling men may be seen waiting for better days, unemployed and passing the time.

The recession adds to a community’s burden in ways that exacerbate prior disadvantage, an expression of how structural forces are mediated by local contexts. I examined data on all housing foreclosure filings in 2009, calculated as a rate per thousand mortgages as of 2007. This measure presents an up-to-date look at the intensity of foreclosures initiated after the economic crisis. Of all communities in Chicago, Washington Park sits at the top. Grand Boulevard, despite the evidence of the middle-class renewal just noted, is ninth highest in the city. The top ten communities in the penetration of foreclosures are all predominantly black.5

As I head further south into Woodlawn, I see further disadvantage and physical disrepair of the housing stock on its western fringes. But as in other visits in recent years, heading eastward toward the lake brings evidence of renewal. New housing, both middle income and mixed income, sprouts on a large number of blocks where tenements once stood. To the extent that Woodlawn is an “outlier,” I would argue that it benefits from its history of organizational action combined with its spatial proximity to the University of Chicago (with its own network of connections to key players) just north. Despite its continuing poverty, for example, Woodlawn ranks thirteenth (in the top quintile) in the city’s distribution of nonprofit organizational density. The Woodlawn Organization (TWO) is one of these organizations, formed back in the early 1960s when distrust of the University of Chicago ran deepest.6 The Reverend Arthur Brazier, pastor emeritus of the Apostolic Church of God, twenty thousand members strong, was at the center of coalition building in Woodlawn ever since he helped bring about TWO’s inception some fifty years ago.7 Although controversial and in some cases distrusted by local residents and accused of caving in to the interests of economic developers at the expense of long-term residents, there can be little doubt that TWO is a political and organizational force. The Key Informant study independently reveals that Woodlawn ranks highest in Chicago on the centralization of organizational contacts in 1995 and in the upper quartile in 2002—networks of influence converge on a small number of leaders within Woodlawn. The provocative alliances formed by TWO and other community organizations, presumably aided by their structural cohesiveness in network contacts, have combined with intervention from the University of Chicago to have sharply altered Woodlawn—for better or worse.

The contextual example of Woodlawn comports with a larger point I have made: when confronted with stark material deprivation and macro forces, neighborhoods must depend on organizational connections both local and that cut across the city and beyond for increasing their capacity in garnering outside resources. These resources are likely to increase in importance as the economic crisis slows housing activity and unemployment lingers at rates most American communities never experience. Hence, consistent with my general findings, stability and change simultaneously exist: Woodlawn’s altered trajectory is relative, and it remains a vulnerable and largely poor community. Its rate of home foreclosures in 2009 is eighth highest in the city.

Heading further south, I revisited Avalon Park and Chatham to see how they are faring in the new economic environment brought on by the recession. I reported in chapter 1 that, unlike their neighbors to the north and west, these black communities have been stably working or middle class for many years. As I passed along the same streets in June of 2010, I noticed many scenes similar to those in the past. In the warm early evening, men and women were out watering their gardens, talking, and relaxing on porches. The feeling was peaceful. Along street after street south of 79th and west of Stony Island, I could see neat brick homes, indicators of block-group associations, and children playing happily. On what seemed like every other block, the signs were especially noticeable, warning off those who would dare tread on the willed tranquility. It was not just the expected drugs and gang activity that were admonished. In the 7900 block of South Dante, as but one example, a sign warned against “loud music,” “walking a dog without a leash,” “ball playing on front,” and “car washing.” Disorder was nowhere to be found in the stereotypical form commonly attributed to black communities, and if the messages on the frequent signs are to be taken as a cultural expression, then shared expectations are solidly mainstream, even if not overtly conservative in nature. This observation corroborates a larger empirical regularity that emerged from the PHDCN study—blacks (and Latinos) in Chicago are less tolerant of activities like drinking and drug use than whites, a regularity that contradicts frequent portrayals in the media.8

But there was change in the air here, as in Woodlawn. The neat brick houses one after another were now interlarded with abandoned or vacant buildings; not every street, but the effect was noticeable enough that it made me take note. In the middle of a block it was not uncommon to see a house or a sequence of two to three houses boarded up or with signs posted on the door, presumably the result of foreclosures. The intrusion of the recession in the form of vacant houses was perhaps not surprising in Washington Park, but in higher-income places like Chatham, to be ranked fourteenth overall in the city in its rate of foreclosures comes as something of a shock to the residents. My visual inspection conformed to the macrolevel data, suggesting that the black working class is experiencing the economic crisis in manifestly negative ways, a qualitative sense of the vulnerable getting poorer. Or, in this case, the working class getting shoved down a notch, with the losses of those foreclosed on shared by the remaining homeowners.

Consistent with a message of this book, the impact of the larger social structure is thus uneven across neighborhoods in ways that are not simply a result of income. In the white working-class or mixed neighborhoods I observed on the same visit in June (e.g., Irving Park, Portage Park, Uptown), I did not see the same evidence of foreclosures, abandonment, or vacancies. Avalon Park and Chatham have seen families raising their kids, tending to their homes, and going about quietly living the American Dream for years, only to be confronted with a new challenge to their housing infrastructures. As if that were not enough, the social infrastructure is being challenged on another more public and explosive front.

Confronting Violence

When people think of the South Side of Chicago, they think violence. In Chatham, that’s not what we see. It’s happened, and we’re going to fix it, so it doesn’t happen again.

Thomas Wortham, president of the Cole Park Advisory Council9

Perhaps linked to the economic crisis or perhaps, as some officials and local residents assert, linked to the infusion of poor families with lots of teenagers from the former “projects,” violence has encroached on the tranquility of Chatham. Whatever the cause, according to local perceptions and some official statistics, violence was up in Chatham’s neighborhoods in 2010, and its threat has become ever more salient, given the proud reputation of the community as a safe haven.10

In the spring of 2010 the papers were full of a heartbreaking story that encapsulates a key theme of this book’s perspective on violence. Community residents of Chatham came together in May to organize against shootings that had erupted in Nat King Cole Park, located at 85th Street and King Drive. Over the years the park had been the site of basketball games, children playing, picnics, and everyday activities enjoyed by families. But in April, a gunman in a van stopped to open fire on a group of teenage males playing basketball. It was the second shooting in weeks. No one died, but the hoops were shut down and an angry community sought to “take back the park.” According to Thomas Wortham, who grew up near the park, as had his father and his grandfather before him, residents were not cowed. Despite the shootings the park was soon filled again with runners, children on swings, and youngsters eager to play ball but now under the watchful eye of adult residents. “Monitoring has to be done,” intoned another resident. Police patrols were also increased, but in a nonacademic expression of collective efficacy, the district commander admitted that the police cannot solve crime alone: “but if we all work together—the police, the community, the elected officials—all of us together … can make a difference with it.”11

Tragically, Chatham would soon bear witness that collective efficacy and policing are not always enough. Despite his and others’ efforts at mobilization, the same Thomas Wortham would come face to face with predatory violence only a week later and yards away. A Chicago police officer and Iraq veteran, Wortham was gunned down on May 19 during an attempted robbery of his new motorcycle after leaving a family dinner at his father’s home, where he had grown up—steps away from Cole Park. Wortham’s father was on the porch that night and yelled when he saw a gun pointed at his son’s head. A retired police sergeant, Wortham’s father went inside to get his own gun and then intervened, in the process shooting one of the three offenders. But it was too late. As his son lay dying, the two other robbers fled in a car, running over the younger Wortham and dragging his body along the block. Shocking the residents of this peaceful neighborhood and across the city, the offenders were allegedly taking part in a drinking game of who could rob someone first. A stunned Mayor Daley was angry: “Here’s a young man who served twice in Iraq.… It should wake up America.”12 The shocks were not over. In rapid fashion two other Chicago police officers were murdered in July of 2010 in separate incidents on the South Side, one just north of Chatham in a similar “safe haven.” The South and West sides witnessed other spasms of violence that took a toll, even if less noticed.13

Unfortunately, predominantly black neighborhoods in Chicago, whether poor, working class, or middle income, have always faced spatial vulnerability to crime to an extent that white neighborhoods of all kinds simply have not. Consistent with the theme of racially uneven exposure, the twenty-year-old man shot while attempting to rob Officer Wortham did not live in the neighborhood, but came from a nearby South Side community, the Wentworth Gardens area just west of the former Robert Taylor Homes. Another apprehended robber came from Englewood, the extremely distressed community to the west of the expressway. Global effects of concentrated disadvantage and spatial vulnerability have been described in earlier chapters, but in this tragic story we see the confluence of mechanisms at work in a single local community. Will Avalon and Chatham Park become the new truly disadvantaged as the black middle class flees, more houses are foreclosed, and poverty rises with the influx of families displaced by the city’s housing authority? Recall the women I described in chapter 1, who unfurled a quilt commemorating all the children murdered in the Robert Taylor Homes in the mid-1990s. Things got so bad in their neighborhood that it no longer exists; rightly or wrongly, implosion was considered the only way out. Will Chatham inexorably decline and one day suffer a similar fate?

I contemplated this question when I could not get the Wortham story out of my mind. My answer, rooted in the findings of this book, is no. The data tell a story of resistance to crime, challenge-inspired collective efficacy, and a long-term stability to the area in its social character, despite underlying structural vulnerabilities. Chatham residents express strong attachments to their community and since the murder seem to be more vigilant than ever in not giving in to violence. More generally, the outpouring over the Wortham murder has spurred collective organizational events (e.g., rallies, neighborhood alliances) and what I would broadly describe as “ratcheted-up” efforts to instill collective efficacy. One resident, for example, stated that residents had banded together in response to the murder because “Unless everybody pulls together, it won’t work.” 14

It is too early to tell definitively, but two months after the Wortham killing and after the media glare had died down, the park was literally “crimefree.” Using geocoded and time-referenced crime data, I did a search for all crimes—minor and major alike—reported to the police occurring within a quarter-mile radius around Cole Park for the two-week period ending July 24, 2010.15 As the map in figure 16.2 shows, the blocks around the park did not produce a single crime, not even so much as a disorderly conduct. On the major thoroughfare of 87th Street near Vernon Avenue, there was a larceny and theft from a car, and a robbery occurred up on 83rd Street. But within and around the park, it was crime free, and with a population of several thousand, the crime rate in the neighborhood has been low when prorated over a year.

FIGURE 16.2. A crimefree Nat King Cole Park, July 11–24, 2010

Why does violence unhinge some communities and draw others together? This book has provided a partial answer. Among the twenty-five predominantly black communities in Chicago (defined as 75 percent or more black), Avalon Park and Chatham rank first and second, respectively in terms of the level of collective efficacy as independently measured in the PHDCN surveys. In terms of organizational participation, I consulted both the nonprofit density data and the PHDCN. Although they are in the middle of the pack in terms of official density of nonprofits, averaged across the two waves of the survey, Avalon Park ranks fifth or in the top 10 percent of organizational participation in the entire city, and it is second among black communities and Chatham is eighth. This performance is notable because neither community boasts a University of Chicago or anything like it in terms of organizational heavyweights. The evidence, then, indicates that there is a relatively strong pool of organizational activity and latent capacity for collective efficacy in these communities, leading me to be optimistic concerning their struggle to remain vibrant.

In addition, I would emphasize that community legacies are not only negative. It would be a mistake to read into my emphasis on mechanisms of social reproduction the idea that poverty and violence are the inevitable stuff of stability. Quite to the contrary, if one recalls the findings in chapter 5, higher-income and low-violence areas have a strong tendency to reproduce themselves as well. There may be no great wealth to transmit in Chatham and Avalon Park, but by cultivating a sense of ownership and cultural commitment to the neighborhood, residents produce a social resource that feeds on itself and serves as a kind of independent protective factor and durable character that encourages action in the face of adversity. Residents are thus far from being duped; they know full well that the South Side they call home is disvalued by many outsiders. But as Wortham was quoted before he was murdered, Chatham residents do not perceive their community solely within the narrative of violence, they actively seek to transcend it: “we’re going to fix it,” he said. One can only hope that his murder was not in vain and that he will ultimately be proven correct, that the pattern in figure 16.2 will be sustained.

Roseland is further on the South Side and nearer to the city limits. It too is a virtually all-black community but more disadvantaged than Avalon Park or Chatham. Roseland is not the worst off by any means, but it is a notch down on the socioeconomic rung and showing signs of distress. It has the tenth-highest foreclosure rate in the city, for example, and faces a tenacious crime problem of its own. With this greater risk comes higher stakes, and the residents seem to recognize this in their outlook. Although the density of formal nonprofits in Roseland is neither high nor low—it sits right at the median—the participation by residents is surprisingly high, given its profile of concentrated poverty.

Of all communities in the city of Chicago, Roseland ranks tenth in organizational participation measured by the PHDCN survey. Among predominantly black communities, it ranks in the upper quintile in collective efficacy as well as organizational participation, and in the upper third of collective action events. These independent data and the pattern of results throughout the book suggest that residents will activate their shared expectations to address, if not always meet, community challenges.

Roseland’s organizational life shone the day I visited. At 6:45 p.m. on June 11 at the intersection of 111th and Wallace, I came across a group of African American men with bright orange shirts standing in the street and approaching passing cars in animated fashion. Curious, I stopped to find out what they were apparently protesting. The men were part of “Roseland Ceasefire,” an organization with citywide roots dedicated to preventing crime.16 On this day they were trying to engage other residents to take increased responsibility for denouncing violence, and also, I suspect, to send a message of hope to local teenagers who were under the threat of gangs. As I watched the action and reactions of passersby, the significance of this spot slowly dawned on me. In the fall of 2009, the nation had watched in horror as Derrion Albert, a sixteen-year-old student, was beaten to death with a wooden plank outside Fenger High School. The beating was part of a large fight among dozens of youth that was deeply unsettling even to those who had seen violence before. Although murders happen frequently in the U.S., this one was videotaped and soon went viral. The video was so chilling that it quickly garnered news attention worldwide, with some claiming the daytime violence outside a school was in part responsible for Chicago losing its Olympic bid soon afterward.17 Fenger High School is just one block south of where the protesters gathered, at 112th and Wallace.

I passed by the school and reflected on the import of Albert’s death and still strong reverberations in the community, given hope by the collective response to violence I had just witnessed but harboring no illusions of a miraculous ending. One of the fundamental principles of collective efficacy is that its interpretation is relative to need and risk. A rich suburban community with little violence usually does not see this type of action, but neither does it need to. The question is what resources are marshaled under what threat, and how to measure latent capacity given that there are many kinds of risk. For example, Hegewisch on Chicago’s Southeast Side faced literal destruction in the early 1990s from Mayor Daley’s proposal to build a third airport. Enraged, “Citizens against the Lake Calumet Airport” rose up to protest not only a powerful political machine but economic powerhouses behind the multibillion-dollar plan. The effort brought together residents, leaders, and organizations. In 1995, Hegewisch’s collective efficacy and density of key-informant leadership ties were among the highest in the city. A residue of increased collective efficacy was likely built up by the airport challenge, but without an underlying capacity in the first place, Hegewisch, like many places before it around the country, would have wilted under pressure. Many runways pave over someone’s former house, after all.

The point then is that, without challenge, efficacy loses meaning. That is why this book proposed an empirical strategy for measuring collective efficacy that was grounded in the theoretical insight that shared expectations given a concrete problem constitute the crucial mechanism in the emergence of action. While Roseland is not well off and faces many risks, foreclosures and violence among them in the summer of 2010, at least some of its residents are taking visible action, and the PHDCN data suggest that the reservoir has not been emptied. One wonders what else is taking place behind the scenes.

A photo I took the day of the rally conveys the contradictions of Roseland (fig. 16.3). An apparently homeless man saunters by in the street, passing homes for sale (foreclosed?) one block away from where a student was publicly slain. The latter alone would crush many communities, but, like Chatham, one can only hope that the angry young men also present in the picture are successful in their struggle to reclaim the very same streets.18 That the protestors are all men should not go unremarked. One of the criticisms of the black community voiced by some observers on the Left and Right alike is that black men in the inner city have not shouldered their responsibilities for raising children and helping to regulate the always difficult road to adulthood of teenagers. Where were the fathers of the boys who stomped Derrion Albert to death, some pointedly asked?19 The prevalence of female-headed families with children in poor communities like Roseland is undeniably high, over 40 percent. But while one incident does not a trend make, the men of Roseland I observed on this day were out, angry, and quite visibly going against the scripts that had written them off as uninvolved.

FIGURE 16.3. Collective protest against violence in Roseland, June 11, 2010. Photograph by the author.

Heading northwest past the Dan Ryan, we find more poverty stretching for hundreds of blocks, reaching hard into communities like Engle-wood and West Englewood. The great recession, along with the deconcentration of large projects like the Robert Taylor Homes, heap more challenges on top of long-term vulnerability and threaten to erase hard-won gains. According to the 2009 data, Englewood and West Englewood represent the third- and fifth-highest foreclosure rates in Chicago, respectively. Moreover, because of their cheap housing to begin with, many CHA voucher holders are moving south and west to communities like Englewood, Washington Park, and South Shore. South suburbs such as Harvey, Country Club Hills, and Dolton are also witnessing a surge of lower-income residents moving in from Chicago.

The new influx of disadvantaged residents highlights the cumulative Matthew Effect process I have emphasized—poor communities with the least resources are taking on added burdens disproportionately, in turn reinforcing preexisting inequality. This cycle of disadvantage is not just structural but cultural in its ability to influence behavior over sustained periods of time. As shown in chapter 13, collective perceptions of disorder are as important as income levels (individual or neighborhood) in driving migration networks between communities. Population flows track community reputational histories, which are shaped in the public’s eye by racial and immigrant concentration (chapter 6) and unwittingly reinforced by institutionalized identities encoded in the media and even the Chicago Local Community Fact Book.20 A vicious cycle emerges, with structural and cultural mechanisms intertwined in their dynamic effects.21

Once again, however, some communities defy simple categorization and the equation in the public’s mind of social problems with particular race and income groupings. Widespread racial stereotypes put highly efficacious areas in the white Far Northwest Side, but consider some anomalies. Although Mount Greenwood is nearby to what is widely thought of as the “Southside Ghetto” and is relatively mixed racially by Chicago standards, it produces high collective efficacy. Beverly is a stable middle-class area even more proximate to the same poverty and more mixed—fully one third of its residents were black in 2000, probably closer to 40 percent by mid-decade. Yet the integrated community of Beverly stands out as the most efficacious community in Chicago overall in 1995 and second best in 2002, after Mount Greenwood. In chapter 7 (fig. 7.3), I showed that Ashburn is also a mixed-race community (43 percent black, 37 percent white, and 17 percent Latino) and yet high in collective efficacy. How do these communities do it? That the extremes of low and high collective efficacy are all on the widely denigrated South Side underscores my claim that social processes must be taken as seriously as demographic composition. Embodied in places like Beverly, Avalon Park, and Chatham, a commonality that stands out beyond residential stability in housing and socioeconomic resources is durable organizational density (or capacity) combined with a strong community identity and commitment to place. Recall from chapters 7–9 that residential stability and organizational density explain neighborhood-level collective efficacy and social altruism net of economic and population composition.

While rare, sometimes even the most disadvantaged communities experience notable changes. The low-income black communities of Oakland and Riverdale, for example, witnessed the largest increases in collective efficacy over time relative to their historical profile and social dynamics occurring elsewhere in the city. As discussed in chapter 5 and highlighted above, Oakland was the site of major structural interventions, including the dismantling of segregated high-rise public housing and public investment by the city. Besides the simple poverty declines, these interventions seem to have boosted both internal and external perceptions of its efficacy. Yet most communities that have achieved high collective efficacy or increased collective efficacy have done so absent such “macro” interventions. Edison and Norwood Park on Chicago’s Northwest Side, for example, are stable high-collective efficacy areas that are virtually all white and that have been middle to upper income for years. Riverdale is on the Far South Side and similarly experienced no major policy or economic interventions. It presents nearly the opposite profile of Edison and Norwood Park—low income and black—but Riverdale managed to increase more in collective efficacy over time, even if it still sits below the baseline level of the Northwest Side cluster. And Mount Greenwood increased over the late 1990s to become the highest-ranking community on the level of collective efficacy by 2002, again absent an “exogenous” intervention. Drawing directly from the findings in chapter 8, I would argue that this upturn came about as a result of the community’s organizational infrastructure. In 1995, prior to the surge in collective efficacy, Mount Greenwood ranked in the top 20 percent (along with Chatham and Avalon Park) in Chicago on the participation of its residents in civic organizations. Beverly was first in organizational participation in 1995, and by 2002 its collective efficacy was second only to Mount Greenwood.

These examples show that while correlations exist between social processes and structural features of economic stratification and racial segregation, they are not isomorphic. Levels and changes in the collective character of communities cannot simply be “read off of demography,” in other words. Moreover, because challenges are not the same in every community, the nature of how collective efficacy evolves and how it unfolds over time varies. There is no one single or invariant pathway, and sometimes unplanned events, like the killing of a police officer at his father’s home or the video of a murder of a local teen, alter trajectories in ways we cannot uncover with our data, even if pervasive mechanisms overlay and shape the higher-order causal picture. Thus, I would argue that collective efficacy and organizational capacity reflect a deeply social and nonreductionist form of community wellbeing.

Bird’s-Eye View Revisited

Using the most recent quantitative data available, I zoom out to take the bird’s-eye view of the social processes I have just described more qualitatively. One key question has been stability and change in economic status. Has the economic or housing crisis altered the city’s relational character, beyond the stories of the different communities told above? Or has global disaster been superimposed on an enduring structure of inequality, and, if so, at what magnitude?

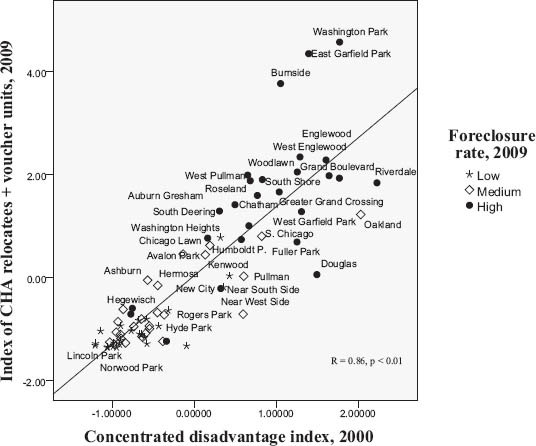

To answer these questions I first examined two sources of data from 2009, one on housing-voucher holders and the other on families displaced from Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) projects.22 Both relocatees from the CHA and housing-voucher users directly reflect families in poverty or that are otherwise economically vulnerable. As expected, when I created per-capita rates in 2009, the two indicators strongly overlapped and produced a high correlation (0.84, p < 0.001). Thus I created a standardized scale that combined the per-capita presence of CHA and voucher users in a community. I then examined its citywide distribution as predicted by the index of concentrated disadvantage in 2000 that I examined in earlier chapters.23 Simultaneously I also examined the rate of home foreclosures filed per mortgage in 2009 after the onset of the Great Recession. The act of foreclosure is a distinct marker of economic and social vulnerability, one that is perhaps more visible to the naked eye through vacancies than the poverty reflected in the CHA measure.

Figure 16.4 shows that inequality’s spatial distribution remains largely intact after the economic crash and major changes in public housing policy in Chicago. The correlation of concentrated disadvantage in 2000 and its parallel in 2009 is notably high, given the measurement difference in indicators, nearly a decade’s worth of race/ethnic change, and much ballyhooed gentrification (R = 0.86, p < 0.01). What’s more, the communities hard hit by home foreclosures after the crash are almost all clustered in the upper-right corner of the figure. Low-foreclosure communities cluster tightly on the bottom left, with a familiar group of names like Beverly and Lincoln Park. There are a few anomalies such as Douglas and Oakland seeing relative “gains” from poor starting points, and with Oakland escaping the worst of the foreclosure crisis. By contrast, Washington Park and East Garfield Park were vulnerable to begin with, only to take on a set of new burdens dished up by Wall Street and the city’s housing authority.24 Overall, however, inequality by place remains highly persistent—knowing a community’s racially linked disadvantage in 2000 pretty much tells you its allocation of CHA relocatees, distribution of the voucher holders, and intensity of foreclosure filings a decade later and after major structural shocks. Rather amazingly, when I create an index of concentrated disadvantage for 1970, it correlates nearly as highly with the CHA poverty index in 2009 as disadvantage in 2000, at 0.67 (p < 0.01). Disadvantage in 1970 also significantly predicts the foreclosure rate in 2009 (0.51, p < 0.01). A forty-year persistence despite the radical turnover of residents indicates yet again the community-level transmission of concentrated poverty. As I have argued, this transmission has structural, cultural, and individual underpinnings, with vulnerability reproduced in part through the systematic sorting over time of individuals, but which chapters 11–13 demonstrated is itself a kind of neighborhood effect. The organizational life of a community plays a role too.

FIGURE 16.4. Inequality’s durable imprint before and after the 2008 economic crisis.

To probe the aftermath of crisis further, especially its organizational character, I examined community-level variations in the foreclosure rate per HUD mortgages during and after the economic meltdown. Prior evidence shows that low income, unemployment (e.g., job loss), and declines in home values are important economic ingredients in home foreclosures.25 Consistent with this finding, concentrated disadvantage in 2000 is highly prognostic, correlated with the foreclosure rate in 2007–9 and in 2009 alone at 0.74 and 0.71, respectively (p < 0.01). More interesting is the systematic variability in foreclosure rates after accounting for economic and racial composition. A key thesis of the book has been that organizational infrastructure exerts a distinct influence on a community’s wellbeing, whether expressed in collective efficacy, other-regarding behavior, collective civic engagement, or lower violence. I extend this reasoning to foreclosures and the global economic crisis. Homes sit in a neighborhood context, after all, and most nonprofit community organizations take it as one of their goals to improve the local social and physical infrastructure, a component of future resale opportunities. It stands to reason that a community’s organizational profile will matter during times of housing crisis. Moreover, many nonprofits directly aim to prevent foreclosures by targeting high-risk neighborhoods. The Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) is especially active in this area and coordinates nonprofit housing organizations in Chicago and around the country. Key mechanisms of support include credit screening, postpurchase training, and mortgage-foreclosure-prevention counseling. I hypothesize, then, that in addition to underlying economic and racial causes, there is a neighborhood organizational component to the intensity of housing foreclosures.26

Although I do not have the data to conduct a state-of-the-art test or prove causality, I examined the rate of foreclosures across Chicago’s seventy-seven community areas as a function of disadvantage (e.g., poverty, unemployment), racial composition, and housing stability. The results confirm the expectation that in areas of greater home ownership there are more home foreclosures, all else equal. Concentrated disadvantage is a major predictor as well, as is racial composition—predominantly black and poor areas suffer disproportionately. But of equal interest and in a further confirmation of the organizational framework put forth in chapter 8, a direct role emerges for the prevalence of nonprofit organizations in a community. I find that communities high in organizational density experienced lower rates of foreclosure, controlling for prior economic, housing, and demographic characteristics.27 The resulting inference is that foreclosure rates vary sharply by local context and that organizational capacity is a protective factor, with those communities that are organizationally “rich” experiencing significantly lower rates of foreclosure no matter what their economic or demographic profile. Thus a twofold process appears to be at work—foreclosure is grafted onto the city’s durable structure of economic and racial ordering, but the organizational capacity of individual communities nonetheless moderates the toll. Community-based prevention is apparently not just for crime.

The Enduring Grip of Violence

A recurring theme in my visits to Chicago’s communities was violence. Despite the heralded crime decline in the U.S. and Chicago, violence remains a problem and one that is anything but randomly distributed by place. Two hypotheses are popular among the public and many scholars: the recession will increase crime, and its geographic shifts are caused by the movement of public-housing residences. I find neither to be true, supporting a thesis of this book. The overarching story is that violence tracks the same community-level sources that it always has.

I collected the most recent data on violence that I could from Chicago Police Department records covering January to July of 2010. Just fewer than fifteen thousand incidents of violence were reported in the city for this period, with a low of three to a high of 1,189 across communities. I calculated the per-capita rate in 2010 and compared it to a period before the major shocks of the economic crisis and public-housing transformation. I selected the rate of violence from 1995 to 2000, a multiyear period of the most rapid declines in violence in the city’s recent history and before the bulk of CHA teardowns. The tenacity of violence’s grip is sobering. Ten years after these large-scale changes, the correlation of violence over time is very high (R = 0.90, p < 0.01),28 rendering a plot unnecessary, especially since communities near the top, bottom, and “off” the diagonal are by now familiar. Chatham and Avalon Park saw modest increases, for example, and Grand Boulevard (formerly the site of the Robert Taylor Homes) and the Near South Side saw decreases, but with a correlation approaching unity, overall rank is strongly preserved. Places like Beverly, Edison Park, and Mount Greenwood thus continue to enjoy a stable peace while communities like Englewood, West Garfield, and Washington Park continue to suffer violence at city-high rates.

The relative stability of violence by community remains obvious. What about hypotheses from earlier chapters on social mechanisms of explanation? I do not aim in this chapter to descend into technical details, but in light of the new data and recent events, I want to try one last time to replicate and update key results. On theoretical grounds, I began with two social processes that have been shown in several chapters to be salient—collective efficacy and collective perceptions of disorder. I examined the association of these factors with 2010 violence rates, controlling for the temporally proximate indicator of concentrated poverty examined above—foreclosure rates and the CHA/voucher density in 2009. Both collective efficacy and perceived disorder in 2002 continue to significantly predict rates of violence in 2010 (R = –0.65 and 0.54, respectively). I then examined simultaneous influences. Low collective efficacy and perceived disorder were independently linked to later rates of violence, even though significantly correlated themselves and both indicators of disadvantage were again controlled.29

As a next step I assessed other neighborhood processes examined in earlier chapters, with a theoretical focus on friend/kinship ties, organizations, and leadership ties. Consistent with the “urban village” finding of chapter 7 and the discussion in chapter 15, dense social ties are related to increased collective efficacy, but they do not directly translate into lower violence. The same picture emerges for organizational density and civic participation, suggesting that the influences of organizations and locally embedded social ties on violence are mediated by collective efficacy. When I went on to estimate changes in key social mechanisms and violence, collectively perceived disorder lost its explanatory power. But increases in collective efficacy in the latter part of the 1990s significantly forecast decreases in crime during the decade of 2000–2010, adjusting for the foreclosures and poverty shifts brought on by the economic crisis.

In a final set of analyses, I examined the variability in violence in the first half of 2010 as a function of both internal neighborhood characteristics and extralocal mechanisms by extending the spatial logic set forth in chapter 10 and the relational concerns of chapters 13 and 14. I found that violence in 2010 continues to have a large spatial correlation that reflects the neighbors of neighborhoods. Still, controlling for the effects of spatial interdependence and the disadvantage index in 2009, both collective efficacy and perceptual disorder measured from 2002 are directly associated with violence in 2010. A one-standard-deviation increase in collective efficacy is associated with approximately a 25 percent reduction in later violence, a magnitude of estimate similar to that reported in chapter 7 and as found in previous work.30 I also controlled for dimensions of cross-community ties in the form of residential migration networks, but the results were similar in pointing to the continued simultaneous influence of internal and extralocal spatial dynamics: concentrated disadvantage, spatial vulnerability in the city’s ecology of violence, and collective efficacy all remained important predictors of future violence. And in the subset of thirty communities in the 2002 KeyNet study, I found that the cohesiveness of leadership ties was directly associated with lower rates of violence in 2010, controlling for concentrated poverty measured in 2009.31

In short, major themes in chapters 5–14 are realized in 2010, despite a historic crime drop, a global economic shock, and a housing crisis. The similar patterns suggest, as argued in chapter 15, that mechanisms of social reproduction are fairly general in their operation: communities constantly change, but in ways that regularly follow social and spatial logics. My bird’s-eye revisit in this section has thus revealed a pattern that reaffirms the thesis at the heart of this book: no matter how much our fate is determined by global or “big” forces, it is experienced locally and shaped by contexts of shared meanings, collective efficacy, and organizational responses.

Altruistic Social Character, Properly Understood

As a final empirical replication, I conducted my own Stanley Milgram–inspired field experiment. In chapter 9 I reported on a large-scale effort to measure other-regarding or socially altruistic behavior in the form of returning letters “lost” in public settings. I argued that retrieving and mailing back a stamped letter is a direct behavioral indicator of anonymous other-regarding propensity. Material payoff and strategic reputation building, common economic explanations of altruism, are implausible. One can argue that returning lost letters is influenced by the location of mailboxes, rain or wind, the season, or the number of people on the street, but these factors can either be randomized by design, controlled, or are randomly distributed across larger communities. Consistent with this claim, I showed in chapter 9 very large differences in letter-return rates across communities after a long list of letter conditions were adjusted. A dropped letter is ignored or not, and this outcome varies substantially by neighborhood context.

The letter-drop field experiment in the early 2000s was carried out over the course of more than a year in conjunction with personal interviewing. More than 3,300 letters were dropped in neighborhoods across the entire city, and an elaborate design was followed. Because of time and resource constraints, I adopted a streamlined plan for the summer of 2010. I chose nine communities on theoretical grounds with the goal of representing variation in key social types. First, I selected the Loop and the Near North Side, examples of dense and seemingly anonymous urban settings. They are often teeming with street life, especially the Loop which is characterized by a very diverse and large daytime population. The Near North alongside the lake is well to do, largely white, cosmopolitan, and almost a stereotype of yuppies (recall also fig. 1.5 and the concentration of high Internet users in this area). Its western edge is poorer and more diverse. The Loop is dominated by businesses and commuters but has an increasingly upscale residence base. Next I chose two middle/working-class communities, one white (Irving Park) and one black (Avalon Park). I then chose two lower-income black areas that also will be familiar to the reader by now. I selected Roseland on the Far South Side and Grand Boulevard on the Near South. Although similar in some respects, there is distinct variation in these two areas according to the pace of gentrification and intervention by housing policy. Next I selected a Latino immigrant community, choosing the Lower West Side (Pilsen). Finally, I chose Uptown and Hyde Park. Although differing in makeup and city location, these communities are heterogeneous or mixed, by most standards, and organizationally dense. Taken as a whole, the nine communities vary by region of the city and a variety of social conditions that capture theoretical contrasts of interest.

My method was purposely simple and designed to control letter-drop conditions and yield similar “ecometric” reliability, as before. I did so through intense concentration of effort, dropping 325 letters over three days, with the number of drops proportionate to the size of each community’s population. The average of thirty-six per community was just under the forty-two of the larger study.32 The overall return rate contradicts narratives of “hunkering down” as a result of the economic crisis, increasing diversity, and a pervasive urban “distance.” Nearly ten years after the first study, with cell-phone distraction among walkers vastly increased, nearly a third (31 percent) of dropped letters were mailed back (N = 102). For the seven communities where letters were dropped during the day, the return rate was a bit higher, at 35 percent.33 This is not materially different than nearly a decade earlier, when the return rate was 37 percent in the same communities.

This result, however, does not tell us if communities switched places in the city’s social order or whether they maintained their profiles. Despite the small number of cases and constraints on statistical power, there is substantial continuity in the community-level structure of other-regarding behavior. The correlation in letter return rates over time is large and significant (R = 0.74, p < 0.05). Grand Boulevard seems to be an outlier of sorts, with an outcome considerably lower than expected based on its prior history. When I remove Grand Boulevard, the association increases to 0.78 (p < 0.05). Perhaps instability in Grand Boulevard due to housing demolitions have unsettled local norms or otherwise dampened other-regarding behavior. But the main story is a substantial “stickiness” in the altruistic social character of the neighborhoods.

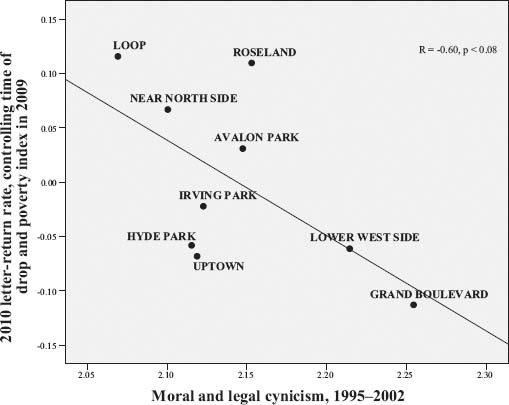

A closer look at how communities are arrayed reveals a third pattern. One might think that the Loop and Near North Side are unwelcome environments for letter returns. On the days I conducted the study, the streets were jammed with people and I was skeptical that anyone would notice, much less mail, a dropped letter. On several occasions I circled back only to watch oblivious pedestrians stepping over my envelopes. Yet notice and return letters people did, in fact at rates higher than all other communities and consistent with the high propensity at the start of the decade. With all due respect to Louis Wirth, the mostly cosmopolitan urbanites of the Near North and Loop are some of the most other-regarding in Chicago. Other than Grand Boulevard, both high-diversity and low-diversity communities (e.g., Hyde Park vs. Rose-land) are not far apart in unadjusted rates of letter returns. Altruistic-type behavior appears to emerge from social norms that are not merely compositional, at least with respect to race or ethnicity. It may be that a poverty effect accounts for why places like Grand Boulevard are at the bottom and wealthy areas like the North Side at the top of the return scale. The negative correlation between poverty and letter returns supports this account (R = –0.73, p < 0.05). A further argument from chapter 9 is that other-regarding behavior derives in part from a community’s organizational and cultural context. In support of this notion, letter-drop return rates are higher where there is a density of organizations (R = 0.58, p = 0.10) and lower in areas of moral/legal cynicism (–0.82, p < 0.01). The latter is especially interesting because it taps a cultural mechanism that was predictive of earlier letter-drop returns.

FIGURE 16.5. Moral/legal cynicism and the attenuation of other-regarding behavior: poverty-adjusted rates of letter-drop return in 2010 by community. Letter-drop return rate in 2010 controls for poverty index (CHA and voucher users) in 2009 and night-drop condition. Moral/legal cynicism scale adjusted for measurement error.

Although the sample is too small to conduct a robust analysis, I probed these ideas further in two strategic ways. First, I examined whether the prior level of moral/legal cynicism is linked to letter returns after controlling for initial (or baseline) propensity. Although the significance levels are compromised by the nine cases, and this is a strict test, given the temporal persistence of letter-return propensity, the negative cynicism coefficient remained significant. Moreover, after I controlled for the indicator of nearly concurrent poverty (the voucher and CHA index of poor residents per capita in 2009), the prior level of cynicism in the community continued to significantly predict a lower 2010 letter-drop return rate while the poverty association was eliminated.34 Figure 16.5 displays the main result across the nine communities. The altruistic character of a community is thus not only enduring, but in combination with results from earlier chapters there is evidence that it may be reproduced over time by concentrated disadvantage and mediating cultural mechanisms of cynicism about the motives of others.

A Concluding Place

Having shown the 2010 version of the larger citywide pattern behind the scenes from individual communities, I end my street-level observations in the concluding chapter where I did in chapter 1, with probably the most famous contrast in the Chicago School history and the site of a major intervention by the city of Chicago. A revisit to Zorbaugh’s classic investigation illuminates in one place the interlocking themes of this book while at the same time offering lessons for how to think about policy and community-level interventions in new ways.