CHAPTER 4

The Basic Equipment and How to Use It

To make wine with concentrated, semi-concentrated, pasteurized, or fresh must, or from whole grapes, a certain number of containers, utensils, and instruments are essential. The material required is less expensive than it might seem at first glance. With a budget of only about $55 Cdn., it is possible to be reasonably well-equipped to make good wine. This is not very much to pay considering that it will allow you to produce wine for about $2 Cdn. per bottle (on the average, taking into account the varying prices of the different qualities of must). Also, you will use this equipment again and again. Of course, as your skill and your desire to reach greater heights in this art grow, you may want to invest in more elaborate, expensive equipment.

If you are a beginner, it is wise to proceed with prudence. Luckily, most retailers of must offer their new customers complete kits at varying prices, depending on the quality of the equipment provided. To give an example, a glass carboy costs more than a plastic fermentor. It is also possible to choose from among several types of hydrometers, some more expensive than others. Generally speaking, the retailers of musts and wine-making equipment are honest with their customers in the matter of prices, as they quite naturally want to cultivate long-term relationships with them.

This chapter describes the most important recipients, utensils, and instruments needed for making wine at home.

The primary fermentor must prevent the must from overflowing. This container must have a large opening to allow the escape of the large quantity of carbon dioxide gas that is released during the first few days of fermentation (and also to allow convenient cleaning). Besides this, to stop the must from overflowing, the capacity of the primary fermentor must be greater than the volume of the must put into it to ferment. There should be at least 10 centimetres (4 inches) left at the top to contain the froth formed by the fermenting must.

Therefore, we suggest a 30-litre container to serve as a primary fermentor for each 23 litres of must, the standard quantity of many of the packaged musts on the market. This quantity of must will yield approximately 30 bottles of wine! The primary fermentor is usually a plastic tub or pail. You will also need plastic sheeting to cover the fermentor. To secure the cover safely, we suggest tying it around with a cord attached to an elastic band at both ends. As an alternative, giant-sized elastic bands (15 cm. or 6 in. long when in repose), are sold in office equipment and stationery stores.

Some primary fermentors have their own lids with a place to install a bung. Although these lids require additional handling, this type of fermentor is becoming increasingly popular because it protects the must from bacteria from outside sources better than other kinds of fermentors. It also offers better protection against any domestic animals (especially those curious cats!) who might end up swimming in the must, ruining five gallons of wine in a few seconds!

If you choose to use a plastic pail that is not white, make sure it is marked “food grade quality”, or “for alimentary use.” Coloured pails that do not carry this label should never be used: they may contain a high degree of lead and are therefore toxic. They can also spoil the wine’s flavour.

Primary fermentors with built-in taps near their base are sold in winemaking supply stores; we do not recommend their use, mainly because the addition of the tap increases the likelihood of contamination by bacteria. If you do own one of these primary fermentors, ask your retailer about the proper way of sanitizing it thoroughly.

Experienced and provident winemakers often prefer to use glass containers, even for the primary fermentation stage. In this case, care should be taken to choose the right size: 20 litres of must can be fermented in a 23-litre carboy, and 23 litres in a 28-litre carboy. In this way, a bung can be fitted into the neck without any risk of overflow. This method is safe and very effective. However, glass carboys require the same amount of attention as the other types of fermentors do (that is, racking when the density goes down to 1.020 or less). Using glass carboys for the primary fermentation stage is inevitably more expensive than using plastic containers; therefore, we only recommend it for people who have been making wine for quite a long time.

A primary fermentor.

For the secondary fermentation stage and for aging in bulk (cuvaison), glass or plastic carboys are generally used. The plastic carboys come in a standard 23-litre format and are made of polyethylene, or polypropylene, which are inert plastics. Thus, no reaction occurs between the material and the wine. They are about five kilograms (11 lbs.) lighter than glass carboys, which makes them easier to handle. Their main disadvantage with respect to glass carboys is that they are relatively opaque, and consequently, it is more difficult to verify the clarity of the wine, or to see if any fermentation is taking place. An even more important factor to consider is that plastic containers cannot be used for wine that is meant to age for more than three months before bottling, as they are not impermeable to air. Oxygen can penetrate the plastic material and oxidate the wine if it is left that long. Also, as we mentioned earlier, the inner walls of plastic fermentors, not being as smooth or as resistant as glass, are more likely to harbour bacteria that may spoil the wine.

We warn you against using the clear plastic bottles that hold commercial brands of mineral water, spring water, or distilled water The material of these containers may start to disintegrate due to the effect of the alcohol, and thus be harmful to the health. The labels on these containers, moreover, normally carry a clear warning against this kind of use.

Thus, glass is definitely preferable for the secondary fermentation stage, particularly if you intend to keep your wine for a considerable period in the carboy for aging in bulk. Even then, take care to choose a glass container with vertical seams (there are usually four of them from the neck to the base). These carboys are less likely to split open than the ones that have a (not very visible) manufacturing seam at the base. The latter type is susceptible to temperature variations, and can break open during use.

Carboys or secondary fermentors are available in several different sizes. The biggest ones can hold 54 litres, but they also come in smaller sizes, with capacities of 4 litres, 11.5 litres, 15 litres, 18 litres, 19 litres, 20 litres, 23 litres, and 28 litres.

Most home winemakers use the 20-litres, 23-litres, and 28-litres carboys, simply because these volumes correspond to the standard quantities of must commonly sold.

Carboys for secondary fermentation and bulk aging.

The debutant winemaker should restrain his or her enthusiasm with regard to size: consider that these mega-bottles have to be manipulated at least two or three times during the winemaking process, and lifting a full 54-litre demijohn is hardly the same as lifting a magnum (1.5 litre) of Champagne!

Caution! Do not wash out glass or plastic carboys with hot water.

Finally, don’t be shocked if you discover that your carboys do not hold exactly the amount indicated. The difference may be one, or even two litres (about half a gallon). However, perfection is rare in this world! You should get used to the little surprises that come up in this pastime, and learn to cheerfully adapt in consequence. Thus, be prepared to discover, when you are racking your wine from one container to another, that you don’t have quite enough to reach the desired level.

Demi-johns, or dames-jeannes.

Demi-johns, or dames-jeannes, are available in several sizes. They are pear-shaped glass bottles, and have either a protective plastic grid or a wicker covering complete with handles. They are actually more practical than plain carboys, but are less appreciated by some amateur winemakers because they are more fragile. They are made of blown glass and therefore, are slightly irregular: some parts may be thinner than others, which makes them more susceptible to breaking than carboys. They also take longer to clean, as it is necessary to remove and replace their protective coverings. However, the covering is not only useful for protecting the glass: it also keeps light from affecting the colour of the wine. Winemakers who appreciate demi-john bottles should therefore leave them the way they were when they were bought; otherwise, they might just as well use conventional carboys instead.

A start-up kit: a primary fermentor, a glass carboy, rigid and flexible tubing, a hydrometer, a fermentation lock and bung, and a stirring spoon.

Of course, it is an advantage to use wooden barrels for aging your own wine: the wine will acquire a better bouquet and finish. However, we only recommend it for experienced winemakers, as it increases the risk of spoiling the wine by contamination. Barrels are generally used for red wine, although Chardonnay and certain other white wines will profit from maturing in barrels as well.

Only barrels appropriate for winemaking should be used. Used barrels should be avoided, particularly if they have been allowed to dry out; it is impossible to safely sanitize a barrel once the staves have dried out and drawn apart.

New barrels for winemaking are expensive; gone are the days when used barrels were completely reconditioned by coopers. Oak barrels from France which have been especially prepared by being exposed to the elements for a period up to ten years are the best, but even North American white oak casks are excellent.

Careful preparations are required before transferring the wine to the barrel. The barrel must be well-soaked with water containing sulphite. You should definitely consult your retailer before embarking on this delicate aspect of wine-making.

There are a few other essential utensils and instruments required in home winemaking. Most of them are quite inexpensive. We will describe them briefly below.

This long plastic spoon usually has two ends, one that is small enough to pass through the neck of the carboy, and the other broader one, for stirring the must in the primary fermentor. It has several uses.

Tubes and Other Instruments Needed for Racking

The safest way to transfer wine from one container to another is by siphoning it. Any other method may cause an unwanted spillage of wine.

For siphoning wine, you will need:

a) A flexible plastic tube or hose, at least 2 metres (6 ft.) long.

b) A rigid tube, usually called a J-tube, at least 10 cm. (4 in.) longer than the height of your carboy. This tube is bent at both ends, at an acute angle at the top and in a J-curve at the bottom. It is placed into the full primary fermentor with the curved end touching the bottom; the tube end will therefore be a little above the bottom and will not draw in the sediment.

Another version of the rigid tube is fitted with a special cap, or anti-sediment tip, which prevents the sediment from entering when the wine is siphoned.

Rigid tube joined to the flexible siphon hose.

The purpose of the acute-angled bend at the top end of the J-tube is simply to prevent the flexible tube from bending over on itself and blocking the flow of the wine as it is drawn out into the new recipient.

c) A clamp to pinch the siphon tube closed at the receiving end; this is an easy way to stop the flow if the recipient appears about to overflow, or for any other reason.

d) A racking tube clip, or hook, is also useful: with the rigid tube pushed through it, it is hooked onto the neck of the carboy, or over the rim of the primary fermentor. In this way, the siphon tube cannot suddenly fall away from the carboy or the fermentor because of a false move on the part of the winemaker.

A hook prevents the rigid tube from falling off the carboy or the fermentor.

Racking by siphoning is a fairly easy operation. Simply position the two containers at different heights, the full one higher than the empty one. Ideally, the bottom of the full container should be level with, or a little bit higher than the neck of the carboy to be filled. When the recipients are in the proper position (with newspapers on the floor in case of spills), place the rigid J-tube inside the full fermentor, stretch out the flexible hose that is attached to the acute-angle end at the top, then suck until the wine has flowed into at least two-thirds of the total length of the siphon hose. Pinch the hose closed with your fingers or with the clamp, then put the unattached end into the empty recipient and release your fingers or the clamp. The pressure created by the difference between the levels will bring all the wine from the elevated fermentor into the lower-placed carboy.

This simple procedure can be enjoyable, unless frequent splashings end up staining your favourite carpet or your natural wood flooring. To be absolutely safe, it is better to put plastic sheeting under the old newspapers.

Winemakers who dislike swallowing any metabisulphite solution or must at the beginning of the racking process can use the Auto-Siphon. This instrument is a cylinder into which is inserted a rigid tube with an acute-angle bend at the top. When using it, make sure the tube reaches to the bottom of the cylinder. Submerge the Auto-Siphon into the liquid to be racked; pump the rigid tube up and down about 15 cm. (6 in.) until the wine flows into the hose, and into the secondary recipient. This instrument works well and is highly appreciated by many home winemakers.

The fermentation lock, also called airlock, has long since replaced, in the name of superior efficiency, the earlier practice of adding a layer of edible oil on top of the wine after siphoning it into the secondary fermentor, or carboy. The purpose of the oil, and of the fermentation lock, is to protect the wine from contact with the air and with bacteria while still allowing the carbon dioxide gas to escape. To accomplish this, a simple solution was found: the installment of a low-pressure barrier between the wine in the carboy and the outside air.

There presently are two types of fermentation lock available. The first one, made of plastic, has a characteristic shape: a transparent tube curved in the form of an S placed horizontally. The bottom extremity of the tube passes through a stopper, usually a rubber bung, which fits into the neck of the carboy. The lock has two enlargements, or wells, half way up two sides of the S. Standard metabisulphite solution is poured into it until it reaches the half-way mark in both of the wells. The gas produced by the slow secondary fermentation in the carboy exerts gradual pressure on the metabisulphite solution, pushing it past the lowest part of the loop of the S. As soon as that point is reached, the excess gas can escape as bubbles rising through the metabisulphite solution into the open air beyond it. Freed from the pressure, the solution returns to its original level, completely protecting the wine from exposure to the air.

It may happen, however, that air is drawn towards the inside of the lock; this is usually due to a rapid change in temperature. In fact, the system works in both directions, but as long as only a small amount of air enters the carboy, no harm is done.

Thus, the fermentation lock is both a simple and ingenious invention which works well as long as the level of liquid is monitored at regular intervals, as any liquid will eventually evaporate.

Watching the level attentively will prevent this from happening.

S-shaped fermentation locks, cylindrical cap locks, and rubber bungs.

The other type of fermentation lock is based on the same principle. It is a capped clear plastic cylinder which fits into the neck of the carboy. Attached inside it (vertically) is a smaller cylinder, or rigid tube, with openings at both the top and bottom; the top of the tube is at a level one-third of the way down from the top of the larger cylinder. The tube continues through the bottom of the bung, or stopper, reaching down into the secondary fermentor (but above the suface of the wine). The metabisulphite solution is poured inside the main cylinder of the lock to just below the top opening of the tube, which is covered by a moveable inverted cap, allowing the gases to escape while preventing bacteria from entering with the returning air. As long as it is working properly, the result is the same as with the first type of lock, that is, the wine is never in contact with the air, and is therefore protected from bacteria that might spoil it.

The cylindrical fermentation lock is generally a more popular choice among home winemakers. Nevertheless, the S-shaped lock has certain advantages over the cylindrical type, even if it is more difficult to clean if a mixture of wine and metabisulphite occurs. This lock has two advantages: its sinuous form slows down the evaporation of the metabisulphate solution, and it makes it much easier to observe any remaining sign of fermentation.

Above all, do not forget to install the little plastic cover on the lock, whichever type you may choose; this will slow evaporation.

The Hydrometer, the Baster, and the Cylinder

One instrument which is used continually throughout the winemaking process is the hydrometer (sometimes known as the densimeter). This is another surprisingly simple instrument of incontestable effectiveness. Usually, the hydrometer is graduated with three scales, the specific gravity (S.G.) scale which is the one most often consulted, the Balling degree, or Brix scale (also used to read specific gravity, particularly in laboratory research in several countries), and finally, the scale used to measure the potential alcohol rate (discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7).

To carry out a density reading with the hydrometer, the home winemaker needs three items: 1) a suction-bulb dropper (or baster) to extract must or wine from the primary or secondary fermentor, 2) a cylinder or testing jar into which the extracted must or wine is poured, and 3) the hydrometer.

The hydrometer itself is a small graduated tube with a weighted bulb at one end which contains a specific mass. This hermetically-sealed, air-filled tube can gauge the specific gravity and evaluate the density of the must quite accurately. We recommend using the 30 cm. (12 in.) hydrometer instead of the 15 cm. (6 in.) one.

Place the hydrometer inside its standard testing jar or cylinder. Using the dropper or baster, add wine or must for the hydrometer rod to float; a reading can then be taken, at the point where the hydrometer emerges from the must or wine. Because the sugar contained in grape-must is denser than alcohol (the specific gravity of alcohol is 0.792, while that of distilled water is 1.000/0.0 Brix-Balling), the hydrometer readings will always be higher before fermentation than after it, when the sugar has largely been transformed into alcohol. The density, or specific gravity of unfermented grape must is normally between 1.075 and 1.095, depending on the amount of sugar contained in the must. When fermentation has taken place, the S.G. reading will be between 0.990 and 0.995 for dry wines, and between 0.995 and 0.998 for wines that are either sweeter or less alcoholic.

The hydrometer is an essential instrument in winemaking.

A dropper, or baster, to extract must or wine.

There is a new type of hydrometer cylinder that can be dipped directly into the must or wine to obtain a sample for a specific gravity reading; this useful instrument is called a wine thief. Place the hydrometer inside the wine thief and lower it through the neck of the carboy (or into the primary fermentor) to draw in a sample by means of the pressure valve at its tip. Draw in enough liquid for the hydrometer to float when the cylinder is in a vertical position, then take the specific gravity reading. The wine or must can be returned to the carboy (or to the primary fermentor) by gently pressing the bottom tip of the cylinder on the neck of the carboy (or on the side of the primary fermentor) which will open the valve and release the contents. Costing a little more than a dropper and cylinder, the wine thief is effective and practical.

The Wine Thief, a hydrometer cylinder equipped with a valve.

The advantage or using a hydrometer is that it makes it easy to verify if the fermentation stage has been successful. After 21 days of fermentation, the hydrometer reading should be less than 1.000. If the reading is higher, it means that the fermentation has stopped before it should have, and that it must be started up again.

The thermometer measures the temperature of the must. Two types are available.

The first type resembles a hydrometer. It is dipped into the must (don’t worry, it floats!) and will register the exact temperature. It is better to use a longer thermometer (30 cm. or 12 in., like the larger model of hydrometer described above): if it falls in, it will be easier to find when it is covered by frothing must in full ferment!

The second type of thermometer is a plastic adhesive strip which is stuck onto the outer surface of the primary fermentor or the carboy. This digital thermometer gives a temperature reading the instant it touches the side of the fermentor. It is inexpensive and very practical, easy to read and instantaneous; moreover, it cannot contaminate the must.

The thermometer is helpful during the alcoholic, or primary fermentation stage, the malolactic fermentation stage, and also during the bulk aging stage.

Stoppers for carboys or demi-johns come in several different sizes. Therefore, it is a good idea to purchase the stopper when buying the container, instead of finding out later that it doesn’t fit. You will know the size is correct when about two-thirds of the stopper enters the neck of the carboy. If the stopper cannot go deep enough, it may eventually move upward, allowing air to get into the carboy. On the other hand, if its diameter is too small, the result may be just as disastrous: the stopper may end up at the bottom of the carboy, which is quite a bother.

Digital thermometers are rapidly supplanting glass ones.

Most stoppers for home winemaking are made of rubber, the ideal material because of its elasticity. Rubber can, however, give your wine an unpleasant taste if the stopper is situated too close to the wine’s surface. There should be at least five centimetres (2 inches) between the bottom of the stopper and the surface of the wine.

Bottling is the last crucial stage of home winemaking. You should have enough bottles ready to be able to store and age your wine. Of course, bottles can be bought especially for this purpose, but why not recycle your own, your friends’ or your neighbours’ bottles? In any case, all bottles must be thoroughly washed with detergent and carefully rinsed. To make this task easier, there are several inexpensive utensils and devices to help you out. These are described below.

A bottle-rinser is a necessity when recycling bottles.

Although they are not included in basic winemaking kits, bottle-rinsers are extremely useful for cleaning the bottoms of bottles, even of carboys. This little apparatus screws on to the kitchen tap (an adapter may be necessary, depending on the type of spout) and shoots water forcefully right to the bottom of the bottles. It dislodges any dirt or residue very effectively and saves you the trouble of scrubbing with a bottle brush. It is well worth its price.

The nickname of this piece of equipment is “the Christmas tree.” Its trunk is circled by several levels of “branches” pointing upward and slightly outward. These hold the upside-down bottles by their necks so that the water left inside completely drains out into the pan at the base of the drainer. This method prevents water from accumulating inside the bottles, inviting bacterial contamination.

Drainer stands.

Once the bottles are completely dry (the two models of drainer hold 44 and 88 bottles respectively), they can either be put into cardboard boxes, or simply left on the “tree.”

A great time-saver: a sulphiter for disinfecting bottles.

This apparatus, which can be installed at the top of the bottle-drainer, is also an extremely practical instrument. It consists of a basin with a fountain jet, or rod, in the middle; standard metabisulphite solution is poured into the basin and the neck of the inverted bottle is fitted over the rod. When the bottle is forced downwards, the pressure makes the jet squirt out a strong rush of solution into the bottle, completely disinfecting the inside of it. This apparatus also costs about $20 Cdn., and is worth its weight in gold for the time it saves. Without it, you would have to pour the meta solution into each bottle with a funnel, swish it around, then funnel it into the next bottle, and so forth. The sulphiter accomplishes the same operation in a single movement, with the solution returning to the basin without any waste. Another advantage of this little machine is that the sulphur fumes are largely prevented from escaping into the surrounding air.

A stop-start bottle-filler.

An essential aid to home winemaking, the bottle-filler is a rigid plastic tube with a siphon valve, or clack valve, on one end. The other end is attached to the flexible tube which will draw the wine from the carboy. The rigid tube is then inserted into the bottle to be filled. By pressing it down against the bottom of the bottle, a rod pushes up to open the valve, allowing the wine to flow into the bottle. When the bottle-filler is lifted out, the flow is cut off as the valve closes. Thus, a bottle can be filled in the twinkling of an eye, with almost no mess (careful, the rod gets stuck sometimes!) as long as you pay attention to the mounting level of wine in the bottle. For approximately $4 Cdn., it’s practically a gift!

A bit more expensive, but even more practical, the automatic bottle filler is placed over the neck of a bottle and fills it to the standard level. It has a secondary tube which takes off the excess wine or foam, and empties it into another recipient beside the bottle. It does the same job as the simple bottle-filler, but also prevents any overflow.

The automatic bottle-filler: easier than the manual one, but more expensive too.

The Enolmatic is another, more sophisticated bottle-filler. Its high price ($300 Cdn.) makes it a piece of equipment that is only worthwhile for people who produce relatively large quantities of wine. It is a vacuum pump that works by suction. It can be hooked up to a filtering apparatus, and can also be used for racking. One marked advantage of this machine is that, because it encloses the wine in a vacuum, it decreases the risk of bacterial contamination.

An expensive apparatus ($300 Cdn.), the Enolmatic is for makers of large quantities of wine.

The corker.

If you decide to provide yourself with a corking apparatus, above all, stay away from models which are not free-standing, as they require superhuman effort and patience. The metal corking stand is almost indestructible and very efficient. It only takes a few seconds to cork a bottle and there is hardly ever any mess if you handle the corker and the corks with care. The important thing is to place the bottle in the proper position; the procedure will then be smooth and successful.

Many home winemakers buy corkers because of their incontestable usefulness. The best kind of corking stand is not very expensive (about $55 Cdn.), considering its excellent durability. If you do not want to buy one, they can also be rented from your retailer at fees varying between $2 and $4 per day.

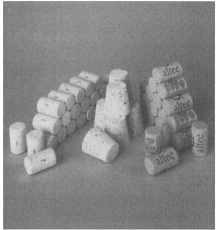

Several different varieties of corks exist; therefore, you should be sure which type is best suited for your winemaking purposes. For example, if you are intending to make a “28-day” type of wine which will be drunk as soon as it is ready, there is no reason for you to buy corks that last for years. It is best to consult your retailer for expert advice on which type of cork to use.

There are many different kinds of corks.

Bottle with plastic stopper and Champagne wire, and capsules.

Plastic Stoppers and Champagne Wires

If you wish to make a sparkling wine, you will have to use plastic Champagne stoppers (corks are very difficult to manipulate when making sparkling wines by the traditional method) and tie them down with Champagne wires to keep them from popping out. You will find the necessary material at your wine-making supply store.

Most amateur winemakers love dressing up their full bottles. You can easily procure ready-made plastic and metallic capsules (the latter type is mostly used for sparkling wines) in a variety of shades and colours, to cover the tops of your bottles.

A large variety of labels are also available; they usually come in packages of 30 each, at a price of about $3 Cdn. They identify your production in a decorative way; they have glue on their reverse sides, for wetting and applying to the bottles.

Capsules give wine bottles a classy, professional appearance.

Labels are held in high esteem by amateur winemakers.

More Expensive, Specialized Equipment

For those who make a lot of wine, a siphon pump may become a necessity. This is simply an electric pump which siphons wine from one carboy to another. Siphon pumps cost quite a lot (between $200 and $300 Cdn.) and are only worthwhile for domestic wine-makers who turn out 500 bottles or more every year, or if the amateur winemaker has back problems, making it risky or painful to lift 20- or 23-litre carboys. This type of pump can also be used to filter wine.

The siphon pump is an expensive apparatus which may be needed by winemakers with back problems.

More and more home winemakers filter their wine for the simple reason that they are proud of it, and want it to compare favourably in appearance with the wines available in stores. And in fact, filtered homemade wines often do attain the clearness of most commercial wines.

Many retailers will lend filtering equipment to their regular customers (or rent them at a very modest fee), but some home winemakers prefer to own their own apparatus. This way, they save themselves the trouble of putting their names on a lengthy waiting list at the winemaking store when the season is at its height.

One model of wine filter.

There are two kinds of wine filters, pressure and vacuum pump filters. Recently, a device which can be fitted with filter cartridges has become available: it is quite effective but not yet perfect. Your best bet is still filtering equipment that incorporates a compressor or a pump.

Filters have different grades of porosity; the wine can be passed through a first set of coarse filters, then through a second set of finer filters, thus attaining perfect clarity.

One little inconvenience arises in filtering: the hydrochloric acid that is used in manufacturing the filter pads must be washed out. This is a rather lengthy operation. We can only hope that soon we will no longer be obliged to circulate water (about 5 gallons of it), then metabisulphite solution (¼ gallon), and finally, distilled water (another gallon) through the pads before using them for the wine!

Filtering apparatus need not be very expensive. Some machines sell at only $50 Cdn., although it may cost you up to $400 if a compressor or a pump is included. We recommend that you buy the most expensive and the best-quality filtering apparatus available. Otherwise, it is better to continue borrowing or renting from your wine equipment store.

If you intend to buy a wine filter, investigate all the products available to be able to choose the best.

Winemakers who use whole grapes as the raw material for their wine, instead of must in one of its forms, need to borrow, rent, or buy two essential (and costly) instruments, the crusher and the press. The crusher is a kind of grinder in the form of a large funnel with a toothed roller at the bottom which is turned by a handle to break open the grapes (without crushing the seeds), allowing the pulp to release its juice.

More sophisticated electric crushers exist, which, as you might expect, cost much more than the manual model. A destemming mechanism is built into some of these.

A grape crusher.

The grapes that have gone through the crusher are then pressed to obtain all of their juice. The wine press is a barrel made of unjoined wooden lathes with an apparatus at the top to press the grapes. It is activated by tightening the vise around the large central screw which forces a round lid down onto the grapes, squeezing their juice out at the bottom and through the spaces between the lathes. The operation continues until the grapes have released all their juice.

In this area too, some models are more efficient (and more expensive) than others.

This concludes our section on the basic equipment used in home wine production. The list is fairly complete. It will give the prospective home winemaker a good idea of the utensils and instruments that he or she needs for the entire process. Of course, we could add others, for example, funnels (very useful at times), and larger siphons for water flow inside the carboys, etc., but the items that we have listed above will certainly stand you in good stead until you develop your own personal style of winemaking, perhaps leading to further requirements.

A wine press.