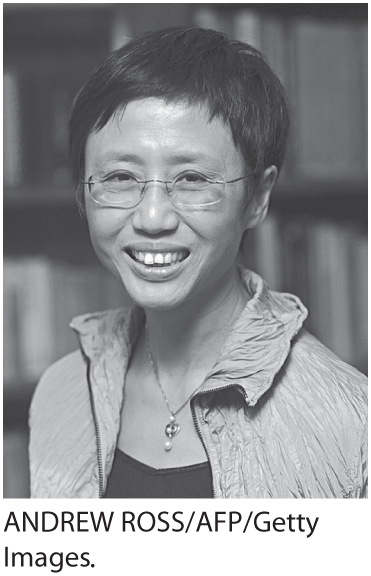

Xu Xi (b. 1954)

Raised in Hong Kong and a resident there until her mid-twenties, Xu Xi graduated from the M.F.A. Program for Poets and Writers at the University of Massachusetts and has taught at the City University of Hong Kong. Among her published fictions are Chinese Walls (1994), Hong Kong Rose (1997), The Unwalled City (2001), Habit of a Foreign Sky (2010), and That Man in Our Lives (2016) and five collections of stories and essays — Daughters of Hui (1996), History’s Fiction (2001), Overleaf Hong Kong (2004), Access: Thirteen Tales (2011), and Insignificance: Hong Kong Stories (2018). “Famine” was chosen for the O. Henry Prize Stories 2006.

Famine 2004

I escape. I board Northwest 18 to New York, via Tokyo. The engine starts, there is no going back. Yesterday, I taught the last English class and left my job of thirty-two years. Five weeks earlier, A-Ma died of heartbreak, within days of my father’s sudden death. He was ninety-five, she ninety. Unlike A-Ba, who saw the world by crewing on tankers, neither my mother nor I ever left Hong Kong.

I never expected my parents to take so long to die.

This meal is luxurious, better than anything I imagined.

My colleagues who fly every summer complain of the indignities of travel. Cardboard food, cramped seats, long lines, and these days, too much security nonsense, they say. They fly Cathay, our “national” carrier. This makes me laugh. We have never been a nation; “national” isn’t our adjective. Semantics, they say, dismissive, just as they dismiss what I say of debt, that it is not an inevitable state, or that children exist to be taught, not spoilt. My colleagues live in overpriced, new, mortgaged flats and indulge 1 to 2.5 children. Most of my students are uneducable.

Back, though, to this in-flight meal. Smoked salmon and cold shrimp, endive salad, strawberries and melon to clean the palate. Then, steak with mushrooms, potatoes au gratin, a choice between a shiraz or cabernet sauvignon. Three cheeses, white chocolate mousse, coffee, and port or a liqueur or brandy. Foods from the pages of a novel, perhaps.

My parents ate sparingly, long after we were no longer impoverished, and disdained “unhealthy” Western diets. A-Ba often said that the only thing he really discovered from travel was that the world was hungry, and that there would never be enough food for everyone. It was why, he said, he did not miss the travel when he retired.

I have no complaints of my travels so far.

My complaining colleagues do not fly business. This seat is an island of a bed, surrounded by air. I did not mean to fly in dignity, but having never traveled in summer, or at all, I didn’t plan months ahead, long before flights filled up. I simply rang the airlines and booked Northwest, the first one that had a seat, only in business class.

Friends and former students, who do fly business when their companies foot the bill, were horrified. You paid full fare? No one does! I have money, I replied, why shouldn’t I? But you’ve given up your “rice bowl.” Think of the future.

I hate rice, always have, even though I never left a single grain, because under my father’s watchful glare, A-Ma inspected my bowl. Every meal, even after her eyes dimmed.

The Plaza Suite is nine hundred square feet, over three times the size of home. I had wanted the Vanderbilt or Ambassador and would have settled for the Louis XV, but they were all booked, by those more important than I, no doubt. Anyway, this will have to do. “Nothing unimportant” happens here at the Plaza is what their website literature claims.

The porter arrives, and wheels my bags in on a trolley.

My father bought our tiny flat in a village in Shatin with his disability settlement. When he was forty-five and I one, a falling crane crushed his left leg and groin, thus ending his sailing and procreating career. Shatin isn’t very rural anymore, but our home has denied progress its due. We didn’t get a phone till I was in my thirties.

I tip the porter five dollars and begin unpacking the leather luggage set. There is too much space for my things.

Right about now, you’re probably wondering, along with my colleagues, former students, and friends, What on earth does she think she’s doing? It was what my parents shouted when I was twelve and went on my first hunger strike.

My parents were illiterate, both refugees from China’s rural poverty. A-Ma fried tofu at Shatin market. Once A-Ba recovered from his accident, he worked there also as a cleaner, cursing his fate. They expected me to support them as soon as possible, which should have been after six years of primary school, the only compulsory education required by law in the sixties.

As you see, I clearly had no choice but to strike, since my exam results proved I was smart enough for secondary school. My father beat me, threatened to starve me. How dare I, when others were genuinely hungry, unlike me, the only child of a tofu seller who always ate. Did I want him and A-Ma to die of hunger just to send me to school? How dare I risk their longevity and old age?

But I was unpacking a Spanish leather suitcase when the past, that country bumpkin’s territory, so rudely interrupted.

Veronica, whom I met years ago at university while taking a literature course, foisted this luggage on me. She runs her family’s garment enterprise, and is married to a banker. Between them and their three children, they own four flats, three cars, and at least a dozen sets of luggage. Veronica invites me out to dinner (she always pays) whenever she wants to complain about her family. Lately, we’ve dined often.

“Kids,” she groaned over our rice porridge, two days before my trip. “My daughter won’t use her brand-new Loewe set because, she says, that’s passé. All her friends at Stanford sling these canvas bags with one fat strap. Canvas, imagine. Not even leather.”

“Ergonomics,” I told her, annoyed at this bland and inexpensive meal. “It’s all about weight and balance.” And cost, I knew, because the young overspend to conform, just as Veronica eats rice porridge because she’s overweight and no longer complains that I’m thin.

She continued. “You’re welcome to take the set if you like.”

“Don’t worry yourself. I can use an old school bag.”

“But that’s barely a cabin bag! Surely not enough to travel with.”

In the end, I let her nag me into taking this set, which is more bag than clothing.

Veronica sounded worried when I left her that evening. “Are you sure you’ll be okay?”

And would she worry, I wonder, if she could see me now, here, in this suite, this enormous space where one night’s bill would have taken my parents years, no, decades, to earn and even for me, four years’ pay, at least when I first started teaching in my rural enclave (though you’re thinking, of course, quite correctly, Well, what about inflation, the thing economists cite to dismiss these longings of an English teacher who has spent her life instructing those who care not a whit for our “official language,” the one they never speak, at least not if they can choose, especially not now when there is, increasingly, a choice).

My unpacking is done; the past need not intrude. I draw a bath, as one does in English literature, to wash away the heat and grime of both cities in summer. Why New York? Veronica asked, at the end of our last evening together. Because, I told her, it will be like nothing I’ve ever known. For the first time since we’ve known each other, Veronica actually seemed to envy me, although perhaps it was my imagination.

The phone rings, and it’s “Guest Relations” wishing to welcome me and offer hospitality. The hotel must wonder, since I grace no social register. I ask for a table at Lutèce tonight. Afterwards, I tip the concierge ten dollars for successfully making the reservation. As you can see, I am no longer an ignorant bumpkin, even though I never left the schools in the New Territories, our urban countryside now that no one farms anymore. Besides, Hong Kong magazines detail lives of the rich and richer so I’ve read of the famous restaurant and know about the greasy palms of New Yorkers.

I order tea and scones from Room Service. It will hold me till dinner at eight.

The first time I ever tasted tea and scones was at the home of my private student. To supplement income when I enrolled in Teacher Training, I tutored Form V students who needed to pass the School Certificate English exam. This was the compromise I agreed to with my parents before they would allow me to qualify as a teacher. Oh yes, there was a second hunger strike two years prior, before they would let me continue into Form IV. That time, I promised to keep working in the markets after school with A-Ma, which I did.

Actually, my learning English at all was a stroke of luck, since I was hardly at a “name school” of the elite. An American priest taught at my secondary school, so I heard a native speaker. He wasn’t a very good teacher, but he paid attention to me because I was the only student who liked the subject. A little attention goes a long way.

Tea and scones! I am supposed to be eating, not dwelling on the ancient past. The opulence of the tray Room Service brings far surpasses what that pretentious woman served, mother of the hopeless boy, my first private student of many, who only passed his English exam because he cheated (he paid a friend to sit the exam for him), not that I’d ever tell since he’s now a wealthy international businessman of some repute who can hire staff to communicate in English with the rest of the world, since he still cannot, at least not with any credibility. That scone (“from Cherikoff,” she bragged) was cold and dry, hard as a rock.

Hot scones, oozing with butter. To ooze. I like the lasciviousness of that word, with its excess of vowels, the way an excess of wealth allows people to waste kindness on me, as my former student still does, every lunar new year, by sending me a laisee packet with a generous check which I deposit in my parents’ bank account, the way I surrender all my earnings, as any filial and responsible unmarried child should, or so they said.

I eat two scones oozing with butter and savor tea enriched by cream and sugar, here at this “greatest hotel in the world,” to vanquish, once and for all, my parents’ fear of death and opulence.

Eight does not come soon enough. In the taxi on the way to Lutèce, I ponder the question of pork.

When we were poor but not impoverished, A-Ma once dared to make pork for dinner. It was meant to be a treat, to give me a taste of meat, because I complained that tofu was bland. A-Ba became a vegetarian after his accident and prohibited meat at home; eunuchs are angry people. She dared because he was not eating with us that night, a rare event in our family (I think some sailors he used to know invited him out).

I shat a tapeworm the next morning — almost ten inches long — and she never cooked pork again.

I have since tasted properly cooked pork, naturally, since it’s unavoidable in Chinese cuisine. In my twenties, I dined out with friends, despite my parents’ objections. But friends marry and scatter; the truth is that there is no one but family in the end, so over time, I submitted to their way of being and seldom took meals away from home, meals my mother cooked virtually till the day she died.

I am distracted. The real question, of course, is whether or not I should order pork tonight.

I did not expect this trip to be fraught with pork!

At Lutèce, I have the distinct impression that the two couples at the next table are talking about me. Perhaps they pity me. People often pitied me my life. Starved of affection, they whispered, although why they felt the need to whisper what everyone could hear I failed to understand. All I desired was greater gastronomic variety, but my parents couldn’t bear the idea of my eating without them. I ate our plain diet and endured their perpetual skimping because they did eventually learn to leave me alone. That much filial propriety was reasonable payment. I just didn’t expect them to stop complaining, to fear for what little fortune they had, because somewhere someone was less fortunate than they. That fear made them cling hard to life, forcing me to suffer their fortitude, their good health, and their longevity.

I should walk over to those overdressed people and tell them how things are, about famine, I mean, the way I tried to tell my students, the way my parents dinned it into me as long as they were alive.

Famine has no menu! The waiter waits as I take too long to study the menu. He does not seem patient, making him an oxymoron in his profession. My students would no more learn the oxymoron than they would learn about famine. Daughter, did you lecture your charges today about famine? A-Ba would ask every night before dinner. Yes, I learned to lie, giving him the answer he needed. This waiter could take a lesson in patience from me.

Finally, I look up at this man who twitches, and do not order pork. Very good, he says, as if I should be graded for my literacy in menus. He returns shortly with a bottle of the most expensive red available, and now I know the people at the next table are staring. The minute he leaves, the taller of the two men from that table comes over.

“Excuse me, but I believe we met in March? At the U.S. Consulate cocktail in Hong Kong? You’re Kwai-sin Ho, aren’t you?” He extends his hand. “Peter Martin.”

Insulted, it’s my turn to stare at this total stranger. I look nothing like that simpering socialite who designs wildly fashionable hats that are all the rage in Asia. Hats! We don’t have the weather for hats, especially not those things, which are good for neither warmth nor shelter from the sun.

Besides, what use are hats for the hungry?

I do not accept his hand. “I’m her twin sister,” I lie. “Kwai-sin and I are estranged.”

He looks like he’s about to protest, but retreats. After that, they don’t stare, although I am sure they discuss me now that I’ve contributed new gossip for those who are nurtured by the crumbs of the rich and famous. But at least I can eat in peace.

It’s my outfit, probably. Kwai-sin Ho is famous for her cheongsams, which is all she ever wears, the way I do. It was my idea. When we were girls together in school, I said the only thing I’d ever wear when I grew up was the cheongsam, the shapely dress with side slits and a neck-strangling collar. She grimaced and said they weren’t fashionable, that only spinster schoolteachers and prostitutes wore them, which, back in the sixties, wasn’t exactly true, but Kwai-sin was never too bright or imaginative.

That was long ago, before she became Kwai-sin in the cheongsam once these turned fashionable again, long before her father died and her mother became the mistress of a prominent businessman who whisked them into the stratosphere high above mine. For a little while, she remained my friend, but then we grew up, she married one of the shipping Hos, and became the socialite who refused, albeit politely, to recognize me the one time we bumped into each other at some function in Hong Kong.

So now, vengeance is mine. I will not entertain the people who fawn over her and possess no powers of recognition.

Food is getting sidelined by memory. This is unacceptable. I cannot allow all these intrusions. I must get back to the food, which is, after all, the point of famine.

This is due to a lack of diligence, as A-Ma would say, this lazy meandering from what’s important, this succumbing to sloth. My mother was terrified of sloth, almost as much as she was terrified of my father.

She used to tell me an old legend about sloth.

There once was a man so lazy he wouldn’t even lift food to his mouth. When he was young, his mother fed him, but as his mother aged, she couldn’t. So he marries a woman who will feed him as his mother did. For a time, life is bliss.

Then one day, his wife must return to her village to visit her dying mother. “How will I eat?” he exclaims in fright. The wife conjures this plan. She bakes a gigantic cookie and hangs it on a string around his neck. All the lazy man must do is bend forward and eat. “Wonderful!” he says, and off she goes, promising to return.

On the first day, the man nibbles the edge of the cookie. Each day, he nibbles further. By the fourth day, he’s eaten so far down there’s no more cookie unless he turns it, which his wife expected he would since he could do this with his mouth.

However, the man’s so lazy he lies down instead and waits for his wife’s return. As the days pass, his stomach growls and begins to eat itself. Yet the man still won’t turn the cookie. By the time his wife comes home, the lazy man has starved to death.

Memory causes such unaccountable digressions! There I was in Lutèce, noticing that people pitied me. Pity made my father livid, which he took out on A-Ma and me. Anger was his one escape from timidity. He wanted no sympathy for either his dead limb or useless genitals.

Perhaps people find me odd rather than pitiful. I will describe my appearance and let you judge. I am thin but not emaciated and have strong teeth. This latter feature is most unusual for a Hong Kong person of my generation. Many years ago, a dentist courted me. He taught me well about oral hygiene, trained as he had been at an American university. Unfortunately, he was slightly rotund, which offended A-Ba. I think A-Ma wouldn’t have minded the marriage, but she always sided with my father, who believed it wise to marry one’s own physical type (illiteracy did not prevent him from developing philosophies, as you’ve already witnessed). I was then in my mid-thirties. After the dentist, there were no other men and as a result, I never left home, which is our custom for unmarried women and men, a loathsome custom but difficult to overthrow. We all must pick our battles, and my acquiring English, which my parents naturally knew not a word, was a sufficiently drastic defiance to last a lifetime, or at least till they expired.

This dinner at Lutèce has come and gone, and you haven’t tasted a thing. It’s what happens when we converse overmuch and do not concentrate on the food. At home, we ate in the silence of A-Ba’s rage.

What a shame, but never mind, I promise to share the bounty next time. This meal must have been good because the bill is in the thousands. I pay by traveler’s checks because, not believing in debt, I own no credit cards.

Last night’s dinner weighs badly, despite my excellent digestion, so I take a long walk late in the afternoon and end up in Chelsea. New York streets are dirtier than I imagined. Although I did not really expect pavements of gold, in my deepest fantasies, there did reign a glitter and sheen.

No one talks to me here.

The air is fetid with the day’s leftover heat and odors. Under a humid, darkening sky, I almost trip over a body on the corner of Twenty-fourth and Seventh. It cannot be a corpse! Surely cadavers aren’t left to rot in the streets.

A-Ma used to tell of a childhood occurrence in her village. An itinerant had stolen food from the local pig trough. The villagers caught him, beat him senseless, cut off his tongue and arms, and left him to bleed to death behind the rubbish heap. In the morning, my mother was at play, and while running, tripped over the body. She fell into a blood pool beside him. The corpse’s eyes were open.

He surely didn’t mean to steal, she always said in the telling, her eyes burning from the memory. Try to forget, my father would say. My parents specialized in memory. They both remained lucid and clearheaded till they died.

But this body moves. It’s a man awakening from sleep. He mumbles something. Startled, I move away. He is still speaking. I think he’s saying he’s hungry.

I escape. A taxi whisks me back to my hotel, where my table is reserved at the restaurant.

The ceiling at the Oak Room is roughly four times the height of an average basketball player. The ambience is not as seductive as promised by the Plaza’s literature. The problem with reading the wrong kind of literature is that you are bound to be disappointed.

This is a man’s restaurant, with a menu of many steaks. Hemingway and Fitzgerald used to eat here. Few of my students have heard of these two, and none of them will have read a single book by either author.

As an English teacher, especially one who was not employed at a “name school” of the elite, I became increasingly marginal. Colleagues and friends converse in Cantonese, the only official language out of our three that people live as well as speak. The last time any student read an entire novel was well over twenty years ago. English literature is not on anyone’s exam roster anymore; to desire it in a Chinese colony is as irresponsible as it was of me to master it in our former British one.

Teaching English is little else than a linguistic requirement. Once, it was my passion and flight away from home. Now it is merely my entrée to this former men’s club.

But I must order dinner and stop thinking about literature.

The entrées make my head spin, so I turn to the desserts. There is no gooseberry tart! Ever since David Copperfield, I have wanted to taste a gooseberry tart (or perhaps it was another book, I don’t remember). I tell the boy with the water jug this.

He says. “The magician, madam?”

“The orphan,” I reply.

He stands, openmouthed, without pouring water. What is this imbecility of the young? They neither serve nor wait.

The waiter appears. “Can I help with the menu?”

“Why?” I snap. “It isn’t heavy.”

But what upsets me is the memory of my mother’s story, which I’d long forgotten until this afternoon, just as I hoped to forget about the teaching of English literature, about the uselessness of the life I prepared so hard for.

The waiter hovers. “Are you feeling okay?”

I look up at the sound of his voice and realize my hands are shaking. Calming myself, I say, “Au jus. The prime rib, please, and escargots to start,” and on and on I go, ordering in the manner of a man who retreats to a segregated club, who indulges in oblivion because he can, who shuts out the stirrings of the groin and the heart.

I wake to a ringing phone. Housekeeping wants to know if they may clean. It’s already past noon. This must be jet lag. I tell Housekeeping, Later.

It’s so comfortable here that I believe it is possible to forget.

I order brunch from Room Service. Five-star hotels in Hong Kong serve brunch buffets on weekends. The first time I went to one, Veronica paid. We were both students at university. She wasn’t wealthy, but her parents gave her spending money, whereas my entire salary (I was already a working teacher by then) belonged to my parents. The array of food made my mouth water. Pace yourself, Veronica said. It’s all you can eat. I wanted to try everything, but gluttony frightened me.

Meanwhile, A-Ba’s voice. After four or more days without food, your stomach begins to eat itself, and his laugh, dry and caustic.

But I was choosing brunch.

Mimosa. Smoked salmon. Omelet with Swiss cheese and chives. And salad, the expensive kind that’s imported back home, crisp Romaine in a Caesar. Room Service asks what I’d like for dessert, so I say chocolate ice-cream sundae. Perhaps I’m more of a bumpkin than I care to admit. My colleagues, former students, and friends would consider my choices boring, unsophisticated, lacking in culinary imagination. They’re right, I suppose, since everything I’ve eaten since coming to New York I could just as easily have obtained back home. They can’t understand, though. It’s not what but how much. How opulent. The opulence is what counts to stop the cannibalism of internal organs.

Will that be all?

I am tempted to say, Bring me an endless buffet, whatever your chef concocts, whatever your tongues desire.

How long till my money runs out, my finite account, ending this sweet exile?

Guest Relations knocks, insistent. I have not let anyone in for three days. I open the door wide to show the manager that everything is fine, that their room is not wrecked, that I am not crazy even if I’m not on the social register. If you read the news, as I do, you know it’s necessary to allay fears. So I do, because I do not wish to give the wrong impression. I am not a diva or an excessively famous person who trashes hotel rooms because she can.

I say, politely, that I’ve been a little unwell, nothing serious, and to please have Housekeeping stop in now. The “please” is significant; it shows I am not odd, that I am, in fact, cognizant of civilized language in English. The manager withdraws, relieved.

For dinner tonight, I decide on two dozen oysters, lobster, and filet mignon. I select a champagne and the wines, one white and one red. Then, it occurs to me that since this is a suite, I can order enough food for a party, so I tell Room Service that there will be a dozen guests for dinner, possibly more. Very good, he says, and asks how many extra bottles of champagne and wine, to which I reply, As many as needed.

My students will be my guests. They more or less were visitors during those years I tried to teach. You mustn’t think I was always disillusioned, though I seem so now. To prove it to you I’ll invite all my colleagues, the few friends I have, like Veronica, the dentist who courted me and his wife and two children, even Kwai-sin and my parents. I bear no grudges; I am not bitter towards them. What I’m uncertain of is whether or not they will come to my supper.

This room, this endless meal, can save me. I feel it. I am vanquishing my fear of death and opulence.

There was a time we did not care about opulence and we dared to speak of death. You spoke of famine because everyone knew the stories from China were true. Now, even in this country, people more or less know. You could educate students about starvation in China or Africa or India because they knew it to be true, because they saw the hunger around them, among the beggars in our streets, and for some, even in their own homes. There was a time it was better not to have space, or things to put in that space, and to dream of having instead, because no one had much, except royalty and movie stars and they were meant to be fantasy — untouchable, unreal — somewhere in a dream of manna and celluloid.

But you can’t speak of famine anymore. Anorexia’s fashionable and desirably profitable on runways, so students simply can’t see the hunger. My colleagues and friends also can’t, and refuse to speak of it, changing the subject to what they prefer to see. Even our journalists can’t seem to see, preferring the reality they fashion rather than the reality that is. I get angry, but then, when I’m calm, I am simply baffled. Perhaps my parents, and friends and colleagues and memory, are right, that I am too stubborn, perhaps even too slothful because instead of seeing reality, I’ve hidden in my parents’ home, in my life as a teacher, even though the years were dreary and long, when what I truly wanted, what I desired, was to embrace the opulence, forsake the hunger, but was too lazy to turn the cookie instead.

I mustn’t be angry at them, by which I mean all the “thems” I know and don’t know, the big impersonal “they.” Like a good English teacher I tell my students, you must define the “they.” Students are students and continue to make the same mistakes, and all I can do is remind them that “they” are you and to please, please, try to remember because language is a root of life.

Most of the people can’t be wrong all the time. Besides, whose fault is it if the dream came true? Postdream is like postmodern; no one understands it, but everyone condones its existence.

Furthermore, what you can’t, or won’t see, doesn’t exist.

Comfort, like food, exists, surrounds me here.

Not wishing to let anger get the better of me, I eat. Like the Romans, I disgorge and continue. It takes hours to eat three lobsters and three steaks, plus consume five glasses of champagne and six of wine, yet still the food is not enough.

The guests arrive and more keep coming. Who would have thought all these people would show up, all these people I thought I left behind. Where do they come from? My students, colleagues, the dentist and his family, a horde of strangers. Even Kwai-sin and her silly hats, and do you know something, we do look a little alike, so Peter Martin wasn’t completely wrong. I changed my language to change my life, but still the past throngs, bringing all these people and their Cantonese chatter. The food is not enough, the food is never enough.

Room Service obliges round the clock.

Veronica arrives and I feel a great relief, because the truth is, I no longer cared for her anymore when all we ate was rice porridge. It was mean-spirited, I was ungrateful, forgetting that once she fed me my first buffet, teasing my appetite. Come out, travel, she urged over the years. It’s not her fault I stayed at home, afraid to abandon my responsibility, traveling only in my mind.

Finally, my parents arrive. My father sits down first to the feast. His leg is whole, and sperm gushes out from between his legs. It’s not so bad here, he says, and gestures for my mother to join him. This is good. A-Ma will eat if A-Ba does, they’re like that, those two. My friends don’t understand, not even Veronica. She repeats now what she often has said, that my parents are “controlling.” Perhaps, I say, but that’s unimportant. I’m only interested in not being responsible anymore.

The noise in the room is deafening. We can barely hear each other above the din. Cantonese is a noisy language, unlike Mandarin or English, but it is alive. This suite that was too empty is stuffed with people, all needing to be fed.

I gaze at the platters of food, piled in this space with largesse. What does it matter if there are too many mouths to feed? A phone call is all it takes to get more food, and more. I am fifty-one and have waited too long to eat. They’re right, they’re all right. If I give in, if I let go, I will vanquish my fears. This is bliss, truly.

A-Ma smiles at the vast quantities of food. This pleases me because she so rarely smiles. She says, Not like lazy cookie man, hah?

Feeling benevolent, I smile at my parents. No, not like him, I say. Now, eat.

Considerations for Critical Thinking and Writing

- FIRST RESPONSE. How does Xu Xi engage the reader in the first three paragraphs of the story?

- Explain how the narrator’s parents’ values and sensibilities are revealed through exposition.

- How do Veronica and Kwai-sin function as foils to the narrator?

- What is the relevance of the narrator’s having been an English teacher for her entire career?

- Do you find any humor in “Famine”? Describe the story’s tone. Is it consistent?

- Choose a paragraph in which Xu Xi uses details particularly well to create a mood, set a scene, or unify the plot, and discuss how that effect is achieved through her carefully chosen language.

- Can you find the story’s theme (or themes) stated directly in a specific paragraph, or is it developed implicitly through the plot, characters, symbols, or some other literary element?

Connections to Other Selections

- Compare the cultural ambitions of the narrator in “Famine” with those of the man in Ralph Ellison’s “King of the Bingo Game.”

- Discuss the narrator’s symbolic relationship to food in “Famine” and in Sally Croft’s poem “Home-Baked Bread.”