Some Principles Of Meter

Poets use rhythm to create pleasurable sound patterns and to reinforce meanings. “Rhythm,” Edith Sitwell once observed, “might be described as, to the world of sound, what light is to the world of sight. It shapes and gives new meaning.” Prose can use rhythm effectively too, but prose that does so tends to be an exception. The following exceptional lines are from a speech by Winston Churchill to the House of Commons after Allied forces lost a great battle to German forces at Dunkirk during World War II:

We shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.

The stressed repetition of “we shall” bespeaks the resolute singleness of purpose that Churchill had to convey to the British people if they were to win the war. Repetition is also one of the devices used in poetry to create rhythmic effects. In the following excerpt from “Song of the Open Road,” Walt Whitman urges the pleasures of limitless freedom on his reader:

Allons!1 the road is before us!

It is safe — I have tried it — my own feet have tried it well — be

not detain’d!

Let the paper remain on the desk unwritten, and the book on the

shelf unopen’d!

Let the tools remain in the workshop! Let the money remain

unearn’d!

Let the school stand! mind not the cry of the teacher!

Let the preacher preach in his pulpit! Let the lawyer plead in the

court, and the judge expound the law.

Camerado,2 I give you my hand!

I give you my love more precious than money,

I give you myself before preaching or law;

Will you give me yourself? will you come travel with me?

Shall we stick by each other as long as we live?

These rhythmic lines quickly move away from conventional values to the open road of shared experiences. Their recurring sounds are created not by rhyme or alliteration and assonance (see Chapter 22) but by the repetition of words and phrases.

Although the repetition of words and phrases can be an effective means of creating rhythm in poetry, the more typical method consists of patterns of accented or unaccented syllables. Words contain syllables that are either stressed or unstressed. A stress (or accent) places more emphasis on one syllable than on another. We say “syllable” not “syllable,” “emphasis” not “emphasis.” We routinely stress syllables when we speak: “Is she content with the contents of the yellow package?” To distinguish between two people we might put special emphasis on a single-syllable word, saying “Is she content…?” In this way stress can be used to emphasize a particular word in a sentence. Poets often arrange words so that the desired meaning is suggested by the rhythm; hence emphasis is controlled by the poet rather than left entirely to the reader.

When a rhythmic pattern of stresses recurs in a poem, the result is meter. Taken together, all the metrical elements in a poem make up what is called the poem’s prosody. Scansion consists of measuring the stresses in a line to determine its metrical pattern. Several methods can be used to mark lines. One widely used system uses ´ for a stressed syllable and ˘ for an unstressed syllable. In a sense, the stress mark represents the equivalent of tapping one’s foot to a beat:

In the first two lines and the final line of this familiar nursery rhyme we hear three stressed syllables. In lines 3 and 4, where the meter changes for variety, we hear just two stressed syllables. The combination of stresses provides the pleasure of the rhythm we hear.

To hear the rhythms of “Hickory, dickory, dock” does not require a formal study of meter. Nevertheless, an awareness of the basic kinds of meter that appear in English poetry can enhance your understanding of how a poem achieves its effects. Understanding the sound effects of a poem and having a vocabulary with which to discuss those effects can intensify your pleasure in poetry. Although the study of meter can be extremely technical, the terms used to describe the basic meters of English poetry are relatively easy to comprehend.

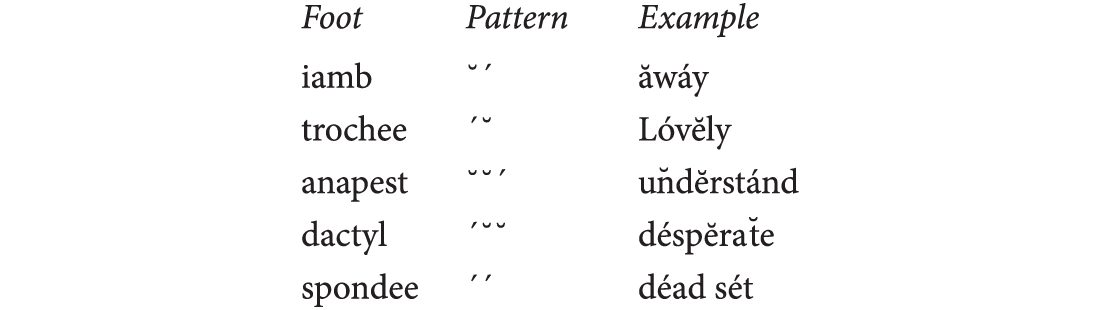

The foot is the metrical unit by which a line of poetry is measured. A foot usually consists of one stressed and one or two unstressed syllables. A vertical line is used to separate the feet:  consists of two feet. A foot of poetry can be arranged in a variety of patterns; here are five of the chief ones:

consists of two feet. A foot of poetry can be arranged in a variety of patterns; here are five of the chief ones:

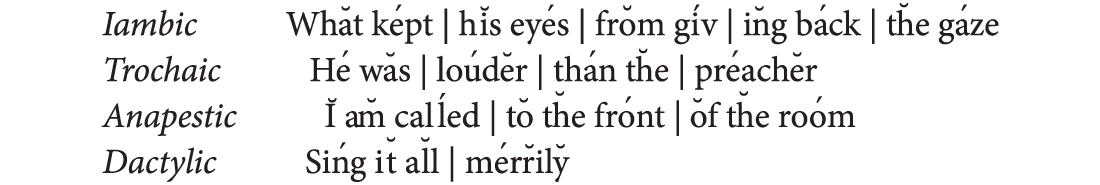

The most common lines in English poetry contain meters based on iambic feet. However, even lines that are predominantly iambic will often include variations to create particular effects. Other important patterns include trochaic, anapestic, and dactylic feet. The spondee is not a sustained meter but occurs for variety or emphasis.

These meters have different rhythms and can create different effects. Iambic and anapestic are known as rising meters because they move from unstressed to stressed sounds, while trochaic and dactylic are known as falling meters. Anapests and dactyls tend to move more lightly and rapidly than iambs or trochees. Although no single kind of meter can be considered always better than another for a given subject, it is possible to determine whether the meter of a specific poem is appropriate for its subject. A serious poem about a tragic death would most likely not be well served by lilting rhythms. Keep in mind, too, that though one or another of these four basic meters might constitute the predominant rhythm of a poem, variations can occur within lines to change the pace or call attention to a particular word.

A line is measured by the number of feet it contains. Here, for example, is an iambic line with three feet: ![A text with stress marks reads, 'If she should write a note'. [f-breve, h- acute, o- breve, r-acute, a-breve, and o- acute stress are marked on the letters.]](../images/meyercbil12e_23_PG658.png) These are the names for line lengths:

These are the names for line lengths:

| monometer: one foot | pentameter: five feet |

| dimeter: two feet | hexameter: six feet |

| trimeter: three feet | heptameter: seven feet |

| tetrameter: four feet | octameter: eight feet |

By combining the name of a line length with the name of a foot, we can describe the metrical qualities of a line concisely. Consider, for example, the pattern of feet and length of this line:

I didn’t want the boy to hit the dog.

The iambic rhythm of this line falls into five feet; hence it is called iambic pentameter. Iambic is the most common pattern in English poetry because its rhythm appears so naturally in English speech and writing. Unrhymed iambic pentameter is called blank verse; Shakespeare’s plays are built on such lines.

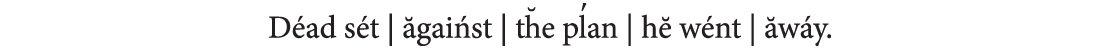

Less common than the iamb, trochee, anapest, or dactyl is the spondee, a two-syllable foot in which both syllables are stressed (´ ´). Note the effect of the spondaic foot at the beginning of this line:

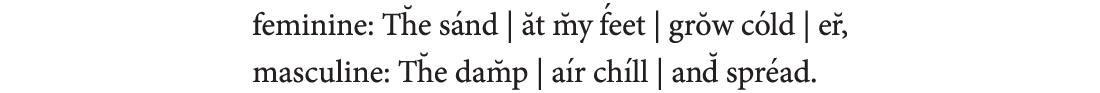

Spondees can slow a rhythm and provide variety and emphasis, particularly in iambic and trochaic lines. Also less common is a pyrrhic foot, which consists of two unstressed syllables, as in Shakespeare’s “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!” Pyrrhic feet are typically variants for iambic verse rather than predominant patterns in lines. A line that ends with a stressed syllable is said to have a masculine ending, whereas a line that ends with an extra unstressed syllable is said to have a feminine ending. Consider, for example, these two lines from Timothy Steele’s “Waiting for the Storm” (the entire poem appears on Timothy Steele’s “Waiting for the Storm”):

The speed of a line is also affected by the number of pauses in it. A pause within a line is called a caesura and is indicated by a double vertical line (||). A caesura can occur anywhere within a line and need not be indicated by punctuation:

Camerado, || I give you my hand!

I give you my love || more precious than money.

A slight pause occurs within each of these lines and at its end. Both kinds of pauses contribute to the lines’ rhythm.

When a line has a pause at its end, it is called an end-stopped line. Such pauses reflect normal speech patterns and are often marked by punctuation. A line that ends without a pause and continues into the next line for its meaning is called a run-on line. Running over from one line to another is also called enjambment. The first and eighth lines of the following poem are run-on lines; the rest are end-stopped.

My Heart Leaps Up 1807

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

Run-on lines have a different rhythm from end-stopped lines. Lines 3 and 4 and lines 8 and 9 are iambic, but the effect of their two rhythms is very different when we read these lines aloud. The enjambment of lines 8 and 9 reinforces their meaning; just as the “days” are bound together, so are the lines.

The rhythm of a poem can be affected by several devices: the kind and number of stresses within lines, the length of lines, and the kinds of pauses that appear within lines or at their ends. In addition, as we saw in Chapter 22, the sound of a poem is affected by alliteration, assonance, rhyme, and consonance. These sounds help to create rhythms by controlling our pronunciations, as in the following lines excerpted from “An Essay on Criticism,” a poem by Alexander Pope:

Soft is the strain when Zephyr gently blows,

And the smooth stream in smoother numbers flows;

But when loud surges lash the sounding shore,

The hoarse, rough verse should like the torrent roar.

These lines are effective because their rhythm and sound work with their meaning.

The following poem demonstrates how you can use an understanding of meter and rhythm to gain a greater appreciation for what a poem is saying.

Waiting for the Storm 1986

The predominant meter of this poem is iambic trimeter, but there is plenty of variation as the storm rapidly approaches and finally begins to pelt the sheltered speaker. The emphatic spondee (“Breeze sent”) pushes the darkness quickly across the bay while the caesura at the end of the sentence in line 2 creates a pause that sets up a feeling of suspense and expectation that is measured in the ticking rhythm of line 4, a run-on line that brings us into the chilly sand and air of the second stanza. Perhaps the most impressive sound effect used in the poem appears in the second syllable of “sounded” in line 7. That “ed” precedes the sound of the poem’s final word, “head,” just as if it were the first drop of rain hitting the hull above the speaker. The visual, tactile, and auditory images make “Waiting for the Storm” an intense sensory experience.

This next poem also reinforces meanings through its use of meter and rhythm.

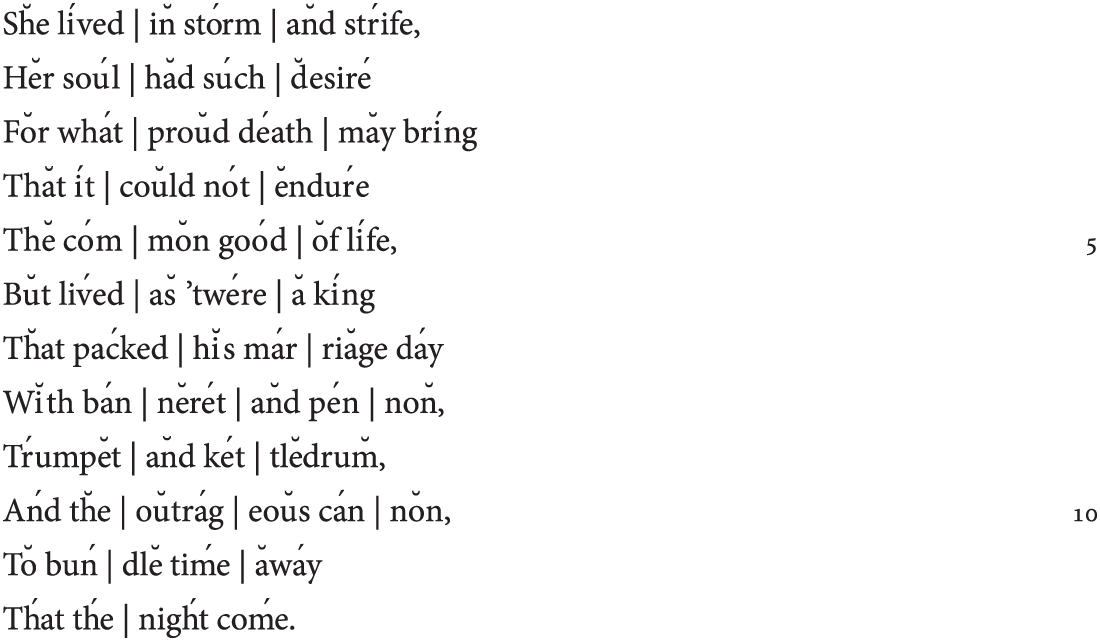

That the Night Come 1912

The poem reads,

She lived [The letter h is unstressed and i is stressed.] vertical bar in storm [The letter n is unstressed and o is stressed.] vertical bar and strife, [The letter n is unstressed and r is stressed.],

Her soul [The letter e is unstressed and u is stressed.] vertical bar had such [The letter a is unstressed and u is stressed.] vertical bar desire [The letter d is unstressed and e is stressed.]

For what [The letter o is unstressed and a is stressed.] vertical bar proud death [The letter u is unstressed and e is stressed.] vertical bar may bring [The letter a is unstressed and i is stressed.]

That it [The letter a is unstressed and i is stressed.] vertical bar could not [The letter u is unstressed and o is stressed.] vertical bar endure [The letter e is unstressed and r is stressed.]

The common [The word common is divided into 2 syllables by a vertical bar. The letter e is unstressed and the first o is stressed and the second is unstressed] good [The first letter o is stressed.] vertical bar of life, [The letter o is unstressed and i is stressed.]

But lived [The letter u is unstressed and v is stressed.] vertical bar as twere [The letter s is unstressed and e is stressed.] vertical bar a king [The letter a is unstressed and i is stressed.]

That packed [The letter h is unstressed and c is stressed.] vertical bar his marriage [The word marriage is divided into 2 syllables by a vertical bar. The letter i in his is unstressed and the first a in marriage is stressed and the second unstressed.] day [The letter a is stressed.]

With banneret [The word banneret is divided into 2 syllables by a vertical bar. The letter i is unstressed and a is stressed and the letter e is unstressed in the first instance and is stressed in the second instance.] vertical bar and pennon [The word pennon is divided into 2 syllables by a vertical bar. The letter a is unstressed and e is stressed and n is unstressed.]

Trumpet [The letter r is unstressed and e is stressed.] vertical bar and kettledrum [In the word kettledrum, ket is divided from the rest of the word by a vertical bar. The letter a in and is unstressed and the first e in kettledrum is stressed. The second e and the letter m are unstressed.]

And the [The letter h is unstressed and n is stressed.] vertical bar outrageous [The word outrageous is divided into 2 syllables by a vertical bar. The first letter o is unstressed and a is stressed The letter u is unstressed.] cannon [The word cannon is divided into 2 syllables by a vertical bar. The letter n is unstressed.]

To bundle [The word bundle is divided into 2 syllables by a vertical bar. The letter o is unstressed, n is stressed, and the letter e is unstressed.] time [The letter m is stressed.] vertical bar away [The letter a unstressed in the first instance and is stressed in the second instance.]

That the [The letter h is stressed in both the instance] vertical bar night come [The letters h and m are stressed].

Scansion reveals that the predominant meter here is iambic trimeter: each line contains three stressed and unstressed syllables that form a regular, predictable rhythm through line 7. That rhythm is disrupted, however, when the speaker compares the woman’s longing for what death brings to a king’s eager anticipation of his wedding night. The king packs the day with noisy fanfares and celebrations to fill up time and distract himself. Unable to accept “The common good of life,” the woman fills her days with “storm and strife.” In a determined effort “To bundle time away,” she, like the king, impatiently awaits the night.

Lines 8–10 break the regular pattern established in the first seven lines. The extra unstressed syllable in lines 8 and 10 along with the trochaic feet in lines 9  and 10

and 10  interrupt the basic iambic trimeter and parallel the woman’s and the king’s frenetic activity. These lines thus echo the inability of the woman and king to “endure” regular or normal time. The last line is the most irregular in the poem. The final two accented syllables sound like the deep resonant beats of a kettledrum or a cannon firing. The words “night come” dramatically remind us that what the woman anticipates is not a lover but the mysterious finality of death. The meter serves, then, in both its regularity and variations to reinforce the poem’s meaning and tone.

interrupt the basic iambic trimeter and parallel the woman’s and the king’s frenetic activity. These lines thus echo the inability of the woman and king to “endure” regular or normal time. The last line is the most irregular in the poem. The final two accented syllables sound like the deep resonant beats of a kettledrum or a cannon firing. The words “night come” dramatically remind us that what the woman anticipates is not a lover but the mysterious finality of death. The meter serves, then, in both its regularity and variations to reinforce the poem’s meaning and tone.

The following poems are especially rich in their rhythms and sounds. As you read and study them, notice how patterns of rhythm and the sounds of words reinforce meanings and contribute to the poems’ effects. And, perhaps most important, read the poems aloud so that you can hear them.