Reading drama responsively

The publication of a short story, novel, or poem represents for most writers the final step in a long creative process that might have begun with an idea, issue, emotion, or question that demanded expression. Playwrights — the wright refers to a craftsman, not to the word write — may begin a work in the same way as other writers, but rarely are they satisfied with only its publication because most plays are written to be performed by actors on a stage before an audience. Playwrights typically create a play keeping in mind not only readers but also actors, producers, directors, costumers, designers, technicians, and a theater full of other support staff who have a hand in presenting the play to a live audience.

Drama is literature equipped with arms, legs, tears, laughs, whispers, shouts, and gestures that are alive and immediate. Indeed, the word drama derives from the Greek word dran, meaning “to do” or “to perform.” The text of many plays — the script — may fully come to life only when the written words are transformed into a performance. Although there are plays that do not invite production, they are relatively few. Such plays, written to be read rather than performed, are called closet dramas. In this kind of work (primarily associated with nineteenth-century English literature), literary art outweighs all other considerations. The majority of playwrights, however, view the written word as the beginning of a larger creation and hope that a producer will deem their scripts worthy of production.

Given that most playwrights intend their works to be performed, it might be argued that reading a play is a poor substitute for seeing it acted on a stage — perhaps something like reading a recipe without having access to the ingredients and a kitchen. This analogy is tempting, but it overlooks the literary dimensions of a script; the words we hear on a stage were written first. Read from a page, these words can feed an imagination in ways that a recipe cannot satisfy a hungry cook. We can fill in a play’s missing faces, voices, actions, and settings in much the same way that we imagine these elements in a short story or novel. Like any play director, we are free to include as many ingredients as we have an appetite for.

This imaginative collaboration with the playwright creates a mental world that can be nearly as real and vivid as a live performance. Sometimes readers find that they prefer their own reading of a play to a director’s interpretation. The title character of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, for instance, has been presented as a whining son, but you may read him as a strong prince. Rich plays often accommodate a wide range of imaginative responses to their texts. Reading, then, is an excellent way to appreciate and evaluate a production of a play. Moreover, reading is valuable in its own right because it allows us to enter the playwright’s created world even when a theatrical production is unavailable.

Reading a play, however, requires more creative imagining than sitting in an audience watching actors on a stage presenting lines and actions before you. As a reader you become the play’s director; you construct an interpretation based on the playwright’s use of language, development of character, arrangement of incidents, description of settings, and directions for staging. Keeping track of the playwright’s handling of these elements will help you to organize your response to the play. You may experience suspense, fear, horror, sympathy, or humor, but whatever experience a play evokes, ask yourself why you respond to it as you do. You may discover that your assessment of Hamlet’s character is different from someone else’s, but whether you find him heroic, indecisive, neurotic, or a complex of competing qualities, you’ll be better equipped to articulate your interpretation of him if you pay attention to your responses and ask yourself questions as you read. Consider, for example, how his reactions might be similar to or different from your own. How does his language reveal his character? Does his behavior seem justified? How would you play the role yourself ? What actor do you think might best play the Hamlet that you have created in your imagination? Why would he or she (women have also played Hamlet onstage) fill the role best?

These kinds of questions (see Questions for Responsive Reading and Writing) can help you to think and talk about your responses to a play. Happily, such questions needn’t — and often can’t — be fully answered as you read the play. Frequently you must experience the entire play before you can determine how its elements work together. That’s why reading a play can be such a satisfying experience. You wouldn’t think of asking a live actor onstage to repeat her lines because you didn’t quite comprehend their significance, but you can certainly reread a page in a book. Rereading allows you to replay language, characters, and incidents carefully and thoroughly to your own satisfaction.

Trifles

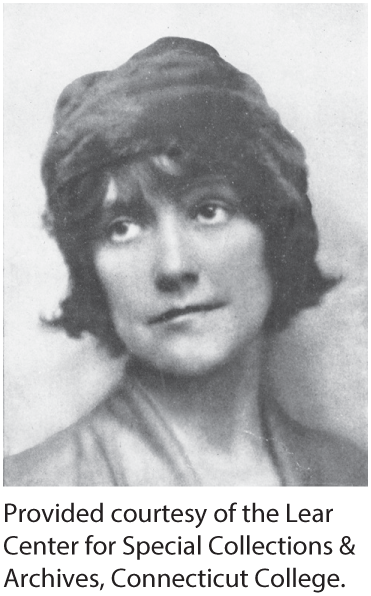

In the following play, Susan Glaspell skillfully draws on many dramatic elements and creates an intense story that is as effective on the page as it is in the theater. Glaspell wrote Trifles in 1916 for the Provincetown Players on Cape Cod, in Massachusetts. Their performance of the work helped her develop a reputation as a writer sensitive to feminist issues. The year after Trifles was produced, Glaspell transformed the play into a short story titled “A Jury of Her Peers.” (A passage from the story appears in the Perspective for comparison.)

Glaspell’s life in the Midwest provided her with the setting for Trifles. Born and raised in Davenport, Iowa, she graduated from Drake University in 1899 and then worked for a short time as a reporter on the Des Moines News, until her short stories were accepted in magazines such as Harper’s and Ladies’ Home Journal. Glaspell moved to the Northeast when she was in her early thirties to continue writing fiction and drama. She published novels, some twenty plays, and more than forty short stories. Alison’s House, based on Emily Dickinson’s life, earned her a Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1931. Trifles and “A Jury of Her Peers” remain, however, Glaspell’s best-known works.

Glaspell wrote Trifles to complete a bill that was to feature several one-act plays by Eugene O’Neill. In The Road to the Temple (1926), she recalls how the play came to her as she sat in the theater looking at a bare stage. First, “the stage became a kitchen…. Then the door at the back opened, and people all bundled up came in — two or three men. I wasn’t sure which, but sure enough about the two women, who hung back, reluctant to enter that kitchen. When I was a newspaper reporter out in Iowa, I was sent down-state to do a murder trial, and I never forgot going to the kitchen of a woman who had been locked up in town.”

Trifles is about a murder committed in a midwestern farmhouse, but the play goes beyond the kinds of questions raised by most whodunit stories. The murder is the occasion instead of the focus. The play’s major concerns are the moral, social, and psychological aspects of the assumptions and perceptions of the men and women who search for the murderer’s motive. Glaspell is finally more interested in the meaning of Mrs. Wright’s life than in the details of Mr. Wright’s death.

As you read the play, keep track of your responses to the characters and note in the margin the moments when Glaspell reveals how men and women respond differently to the evidence before them. What do those moments suggest about the kinds of assumptions these men and women make about themselves and each other? How do their assumptions compare with your own?

Trifles 1916

CHARACTERS

George Henderson, county attorney

Henry Peters, sheriff

Lewis Hale, a neighboring farmer

Mrs. Peters

Mrs. Hale

SCENE: The kitchen in the now abandoned farmhouse of John Wright, a gloomy kitchen, and left without having been put in order — unwashed pans under the sink, a loaf of bread outside the breadbox, a dish towel on the table — other signs of incompleted work. At the rear the outer door opens and the Sheriff comes in followed by the County Attorney and Hale. The Sheriff and Hale are men in middle life, the County Attorney is a young man; all are much bundled up and go at once to the stove. They are followed by the two women — the Sheriff’s wife first; she is a slight wiry woman, a thin nervous face. Mrs. Hale is larger and would ordinarily be called more comfortable looking, but she is disturbed now and looks fearfully about as she enters. The women have come in slowly, and stand close together near the door.

County Attorney (rubbing his hands): This feels good. Come up to the fire, ladies.

Mrs. Peters (after taking a step forward): I’m not — cold.

Sheriff (unbuttoning his overcoat and stepping away from the stove as if to mark the beginning of official business): Now, Mr. Hale, before we move things about, you explain to Mr. Henderson just what you saw when you came here yesterday morning.

County Attorney: By the way, has anything been moved? Are things just as you left them yesterday?

Sheriff (looking about): It’s just about the same. When it dropped below zero last night I thought I’d better send Frank out this morning to make a fire for us — no use getting pneumonia with a big case on, but I told him not to touch anything except the stove — and you know Frank.

County Attorney: Somebody should have been left here yesterday.

Sheriff: Oh — yesterday. When I had to send Frank to Morris Center for that man who went crazy — I want you to know I had my hands full yesterday. I knew you could get back from Omaha by today and as long as I went over everything here myself —

County Attorney: Well, Mr. Hale, tell just what happened when you came here yesterday morning.

Hale: Harry and I had started to town with a load of potatoes. We came along the road from my place and as I got here I said, “I’m going to see if I can’t get John Wright to go in with me on a party telephone.” I spoke to Wright about it once before and he put me off, saying folks talked too much anyway, and all he asked was peace and quiet — I guess you know about how much he talked himself; but I thought maybe if I went to the house and talked about it before his wife, though I said to Harry that I didn’t know as what his wife wanted made much difference to John —

County Attorney: Let’s talk about that later, Mr. Hale. I do want to talk about that, but tell now just what happened when you got to the house.

Hale: I didn’t hear or see anything; I knocked at the door, and still it was all quiet inside. I knew they must be up, it was past eight o’clock. So I knocked again, and I thought I heard somebody say, “Come in.” I wasn’t sure, I’m not sure yet, but I opened the door — this door (indicating the door by which the two women are still standing) and there in that rocker — (pointing to it) sat Mrs. Wright. (They all look at the rocker.)

County Attorney: What — was she doing?

Hale: She was rockin’ back and forth. She had her apron in her hand and was kind of — pleating it.

County Attorney: And how did she — look?

Hale: Well, she looked queer.

County Attorney: How do you mean — queer?

Hale: Well, as if she didn’t know what she was going to do next. And kind of done up.

County Attorney: How did she seem to feel about your coming?

Hale: Why, I don’t think she minded — one way or other. She didn’t pay much attention. I said, “How do, Mrs. Wright, it’s cold, ain’t it?” And she said, “Is it?” — and went on kind of pleating at her apron. Well, I was surprised; she didn’t ask me to come up to the stove, or to set down, but just sat there, not even looking at me, so I said, “I want to see John.” And then she — laughed. I guess you would call it a laugh. I thought of Harry and the team outside, so I said a little sharp: “Can’t I see John?” “No,” she says, kind o’ dull like. “Ain’t he home?” says I. “Yes,” says she, “he’s home.” “Then why can’t I see him?” I asked her, out of patience. “ ’Cause he’s dead,” says she. “Dead?” says I. She just nodded her head, not getting a bit excited, but rockin’ back and forth. “Why — where is he?” says I, not knowing what to say. She just pointed upstairs — like that (himself pointing to the room above). I started for the stairs, with the idea of going up there. I walked from there to here — then I says, “Why, what did he die of ?” “He died of a rope round his neck,” says she, and just went on pleatin’ at her apron. Well, I went out and called Harry. I thought I might — need help. We went upstairs and there he was lyin’ —

County Attorney: I think I’d rather have you go into that upstairs, where you can point it all out. Just go on now with the rest of the story.

Hale: Well, my first thought was to get that rope off. It looked … (stops; his face twitches) … but Harry, he went up to him, and he said, “No, he’s dead all right, and we’d better not touch anything.” So we went back downstairs. She was still sitting that same way. “Has anybody been notified?” I asked. “No,” says she, unconcerned. “Who did this, Mrs. Wright?” said Harry. He said it businesslike — and she stopped pleatin’ of her apron. “I don’t know,” she says. “You don’t know?” says Harry. “No,” says she. “Weren’t you sleepin’ in the bed with him?” says Harry. “Yes,” says she, “but I was on the inside.” “Somebody slipped a rope round his neck and strangled him and you didn’t wake up?” says Harry. “I didn’t wake up,” she said after him. We must ’a’ looked as if we didn’t see how that could be, for after a minute she said, “I sleep sound.” Harry was going to ask her more questions but I said maybe we ought to let her tell her story first to the coroner, or the sheriff, so Harry went fast as he could to Rivers’ place, where there’s a telephone.

County Attorney: And what did Mrs. Wright do when she knew that you had gone for the coroner?

Hale: She moved from the rocker to that chair over there (pointing to a small chair in the corner) and just sat there with her hands held together and looking down. I got a feeling that I ought to make some conversation, so I said I had come in to see if John wanted to put in a telephone, and at that she started to laugh, and then she stopped and looked at me — scared. (The County Attorney, who has had his notebook out, makes a note.) I dunno, maybe it wasn’t scared. I wouldn’t like to say it was. Soon Harry got back, and then Dr. Lloyd came and you, Mr. Peters, and so I guess that’s all I know that you don’t.

County Attorney (looking around): I guess we’ll go upstairs first — and then out to the barn and around there. (To the Sheriff.) You’re convinced that there was nothing important here — nothing that would point to any motive?

Sheriff: Nothing here but kitchen things. (The County Attorney, after again looking around the kitchen, opens the door of a cupboard closet. He gets up on a chair and looks on a shelf. Pulls his hand away, sticky.)

County Attorney: Here’s a nice mess. (The women draw nearer.)

Mrs. Peters (to the other woman): Oh, her fruit; it did freeze. (To the Lawyer.) She worried about that when it turned so cold. She said the fire’d go out and her jars would break.

Sheriff (rises): Well, can you beat the woman! Held for murder and worryin’ about her preserves.

County Attorney: I guess before we’re through she may have something more serious than preserves to worry about.

Hale: Well, women are used to worrying over trifles. (The two women move a little closer together.)

County Attorney (with the gallantry of a young politician): And yet, for all their worries, what would we do without the ladies? (The women do not unbend. He goes to the sink, takes a dipperful of water from the pail, and pouring it into a basin, washes his hands. Starts to wipe them on the roller towel, turns it for a cleaner place.) Dirty towels! (Kicks his foot against the pans under the sink.) Not much of a housekeeper, would you say, ladies?

Mrs. Hale (stiffly): There’s a great deal of work to be done on a farm.

County Attorney: To be sure. And yet (with a little bow to her) I know there are some Dickson county farmhouses which do not have such roller towels. (He gives it a pull to expose its full length again.)

Mrs. Hale: Those towels get dirty awful quick. Men’s hands aren’t always as clean as they might be.

County Attorney: Ah, loyal to your sex, I see. But you and Mrs. Wright were neighbors. I suppose you were friends, too.

Mrs. Hale (shaking her head): I’ve not seen much of her of late years. I’ve not been in this house — it’s more than a year.

County Attorney: And why was that? You didn’t like her?

Mrs. Hale: I liked her all well enough. Farmers’ wives have their hands full, Mr. Henderson. And then —

County Attorney: Yes — ?

Mrs. Hale (looking about): It never seemed a very cheerful place.

County Attorney: No — it’s not cheerful. I shouldn’t say she had the homemaking instinct.

Mrs. Hale: Well, I don’t know as Wright had, either.

County Attorney: You mean that they didn’t get on very well?

Mrs. Hale: No, I don’t mean anything. But I don’t think a place’d be any cheerfuller for John Wright’s being in it.

County Attorney: I’d like to talk more of that a little later. I want to get the lay of things upstairs now. (He goes to the left where three steps lead to a stair door.)

Sheriff: I suppose anything Mrs. Peters does’ll be all right. She was to take in some clothes for her, you know, and a few little things. We left in such a hurry yesterday.

County Attorney: Yes, but I would like to see what you take, Mrs. Peters, and keep an eye out for anything that might be of use to us.

Mrs. Peters: Yes, Mr. Henderson. (The women listen to the men’s steps on the stairs, then look about the kitchen.)

Mrs. Hale: I’d hate to have men coming into my kitchen, snooping around and criticizing. (She arranges the pans under sink which the lawyer had shoved out of place.)

Mrs. Peters: Of course it’s no more than their duty.

Mrs. Hale: Duty’s all right, but I guess that deputy sheriff that came out to make the fire might have got a little of this on. (Gives the roller towel a pull.) Wish I’d thought of that sooner. Seems mean to talk about her for not having things slicked up when she had to come away in such a hurry.

Mrs. Peters (who has gone to a small table in the left rear corner of the room, and lifted one end of a towel that covers a pan): She had bread set. (Stands still.)

Mrs. Hale (eyes fixed on a loaf of bread beside the breadbox, which is on a low shelf at the other side of the room. Moves slowly toward it.): She was going to put this in there. (Picks up loaf, then abruptly drops it. In a manner of returning to familiar things.) It’s a shame about her fruit. I wonder if it’s all gone. (Gets up on the chair and looks.) I think there’s some here that’s all right, Mrs. Peters. Yes — here; (holding it toward the window) this is cherries, too. (Looking again.) I declare I believe that’s the only one. (Gets down, bottle in her hand. Goes to the sink and wipes it off on the outside.) She’ll feel awful bad after all her hard work in the hot weather. I remember the afternoon I put up my cherries last summer. (She puts the bottle on the big kitchen table, center of the room. With a sigh, is about to sit down in the rocking-chair. Before she is seated realizes what chair it is; with a slow look at it, steps back. The chair which she has touched rocks back and forth.)

Mrs. Peters: Well, I must get those things from the front room closet. (She goes to the door at the right, but after looking into the other room, steps back.) You coming with me, Mrs. Hale? You could help me carry them. (They go in the other room; reappear, Mrs. Peters carrying a dress and skirt, Mrs. Hale following with a pair of shoes.) My, it’s cold in there. (She puts the clothes on the big table, and hurries to the stove.)

Mrs. Hale (examining the skirt): Wright was close. I think maybe that’s why she kept so much to herself. She didn’t even belong to the Ladies’ Aid. I suppose she felt she couldn’t do her part, and then you don’t enjoy things when you feel shabby. I heard she used to wear pretty clothes and be lively, when she was Minnie Foster, one of the town girls singing in the choir. But that — oh, that was thirty years ago. This all you want to take in?

Mrs. Peters: She said she wanted an apron. Funny thing to want, for there isn’t much to get you dirty in jail, goodness knows. But I suppose just to make her feel more natural. She said they was in the top drawer in this cupboard. Yes, here. And then her little shawl that always hung behind the door. (Opens stair door and looks.) Yes, here it is. (Quickly shuts door leading upstairs.)

Mrs. Hale (abruptly moving toward her): Mrs. Peters?

Mrs. Peters: Yes, Mrs. Hale?

Mrs. Hale: Do you think she did it?

Mrs. Peters (in a frightened voice): Oh, I don’t know.

Mrs. Hale: Well, I don’t think she did. Asking for an apron and her little shawl. Worrying about her fruit.

Mrs. Peters (starts to speak, glances up, where footsteps are heard in the room above. In a low voice): Mr. Peters says it looks bad for her. Mr. Henderson is awful sarcastic in a speech and he’ll make fun of her sayin’ she didn’t wake up.

Mrs. Hale: Well, I guess John Wright didn’t wake when they was slipping that rope under his neck.

Mrs. Peters: No, it’s strange. It must have been done awful crafty and still. They say it was such a — funny way to kill a man, rigging it all up like that.

Mrs. Hale: That’s just what Mr. Hale said. There was a gun in the house. He says that’s what he can’t understand.

Mrs. Peters: Mr. Henderson said coming out that what was needed for the case was a motive; something to show anger, or — sudden feeling.

Mrs. Hale (who is standing by the table): Well, I don’t see any signs of anger around here. (She puts her hand on the dish towel which lies on the table, stands looking down at table, one-half of which is clean, the other half messy.) It’s wiped to here. (Makes a move as if to finish work, then turns and looks at loaf of bread outside the breadbox. Drops towel. In that voice of coming back to familiar things.) Wonder how they are finding things upstairs. I hope she had it a little more red-up up there. You know, it seems kind of sneaking. Locking her up in town and then coming out here and trying to get her own house to turn against her!

Mrs. Peters: But, Mrs. Hale, the law is the law.

Mrs. Hale: I s’pose ’tis. (Unbuttoning her coat.) Better loosen up your things, Mrs. Peters. You won’t feel them when you go out. (Mrs. Peters takes off her fur tippet, goes to hang it on hook at back of room, stands looking at the under part of the small corner table.)

Mrs. Peters: She was piecing a quilt. (She brings the large sewing basket and they look at the bright pieces.)

Mrs. Hale: It’s a log cabin pattern. Pretty, isn’t it? I wonder if she was goin’ to quilt it or just knot it? (Footsteps have been heard coming down the stairs. The Sheriff enters followed by Hale and the County Attorney.)

Sheriff: They wonder if she was going to quilt it or just knot it! (The men laugh, the women look abashed.)

County Attorney (rubbing his hands over the stove): Frank’s fire didn’t do much up there, did it? Well, let’s go out to the barn and get that cleared up. (The men go outside.)

Mrs. Hale (resentfully): I don’t know as there’s anything so strange, our takin’ up our time with little things while we’re waiting for them to get the evidence. (She sits down at the big table smoothing out a block with decision.) I don’t see as it’s anything to laugh about.

Mrs. Peters (apologetically): Of course they’ve got awful important things on their minds. (Pulls up a chair and joins Mrs. Hale at the table.)

Mrs. Hale (examining another block): Mrs. Peters, look at this one. Here, this is the one she was working on, and look at the sewing! All the rest of it has been so nice and even. And look at this! It’s all over the place! Why, it looks as if she didn’t know what she was about! (After she has said this they look at each other, then start to glance back at the door. After an instant Mrs. Hale has pulled at a knot and ripped the sewing.)

Mrs. Peters: Oh, what are you doing, Mrs. Hale?

Mrs. Hale (mildly): Just pulling out a stitch or two that’s not sewed very good. (Threading a needle.) Bad sewing always made me fidgety.

Mrs. Peters (nervously): I don’t think we ought to touch things.

Mrs. Hale: I’ll just finish up this end. (Suddenly stopping and leaning forward.) Mrs. Peters?

Mrs. Peters: Yes, Mrs. Hale?

Mrs. Hale: What do you suppose she was so nervous about?

Mrs. Peters: Oh — I don’t know. I don’t know as she was nervous. I sometimes sew awful queer when I’m just tired. (Mrs. Hale starts to say something, looks at Mrs. Peters, then goes on sewing.) Well, I must get these things wrapped up. They may be through sooner than we think. (Putting apron and other things together.) I wonder where I can find a piece of paper, and string. (Rises.)

Mrs. Hale: In that cupboard, maybe.

Mrs. Peters (looking in cupboard): Why, here’s a bird-cage. (Holds it up.) Did she have a bird, Mrs. Hale?

Mrs. Hale: Why, I don’t know whether she did or not — I’ve not been here for so long. There was a man around last year selling canaries cheap, but I don’t know as she took one; maybe she did. She used to sing real pretty herself.

Mrs. Peters (glancing around): Seems funny to think of a bird here. But she must have had one, or why would she have a cage? I wonder what happened to it?

Mrs. Hale: I s’pose maybe the cat got it.

Mrs. Peters: No, she didn’t have a cat. She’s got that feeling some people have about cats — being afraid of them. My cat got in her room and she was real upset and asked me to take it out.

Mrs. Hale: My sister Bessie was like that. Queer, ain’t it?

Mrs. Peters (examining the cage): Why, look at this door. It’s broke. One hinge is pulled apart.

Mrs. Hale (looking too): Looks as if someone must have been rough with it.

Mrs. Peters: Why, yes. (She brings the cage forward and puts it on the table.)

Mrs. Hale: I wish if they’re going to find any evidence they’d be about it. I don’t like this place.

Mrs. Peters: But I’m awful glad you came with me, Mrs. Hale. It would be lonesome for me sitting here alone.

Mrs. Hale: It would, wouldn’t it? (Dropping her sewing.) But I tell you what I do wish, Mrs. Peters. I wish I had come over sometimes when she was here. I — (looking around the room) — wish I had.

Mrs. Peters: But of course you were awful busy, Mrs. Hale — your house and your children.

Mrs. Hale: I could’ve come. I stayed away because it weren’t cheerful — and that’s why I ought to have come. I — I’ve never liked this place. Maybe because it’s down in a hollow and you don’t see the road. I dunno what it is, but it’s a lonesome place and always was. I wish I had come over to see Minnie Foster sometimes. I can see now — (Shakes her head.)

Mrs. Peters: Well, you mustn’t reproach yourself, Mrs. Hale. Somehow we just don’t see how it is with other folks until — something turns up.

Mrs. Hale: Not having children makes less work — but it makes a quiet house, and Wright out to work all day, and no company when he did come in. Did you know John Wright, Mrs. Peters?

Mrs. Peters: Not to know him; I’ve seen him in town. They say he was a good man.

Mrs. Hale: Yes — good; he didn’t drink, and kept his word as well as most, I guess, and paid his debts. But he was a hard man, Mrs. Peters. Just to pass the time of day with him — (Shivers.) Like a raw wind that gets to the bone. (Pauses, her eye falling on the cage.) I should think she would ’a’ wanted a bird. But what do you suppose went with it?

Mrs. Peters: I don’t know, unless it got sick and died. (She reaches over and swings the broken door, swings it again, both women watch it.)

Mrs. Hale: You weren’t raised round here, were you? (Mrs. Peters shakes her head.) You didn’t know — her?

Mrs. Peters: Not till they brought her yesterday.

Mrs. Hale: She — come to think of it, she was kind of like a bird herself — real sweet and pretty, but kind of timid and — fluttery. How — she — did — change. (Silence: then as if struck by a happy thought and relieved to get back to everyday things.) Tell you what, Mrs. Peters, why don’t you take the quilt in with you? It might take up her mind.

Mrs. Peters: Why, I think that’s a real nice idea, Mrs. Hale. There couldn’t possibly be any objection to it could there? Now, just what would I take? I wonder if her patches are in here — and her things. (They look in the sewing basket.)

Mrs. Hale: Here’s some red. I expect this has got sewing things in it. (Brings out a fancy box.) What a pretty box. Looks like something somebody would give you. Maybe her scissors are in here. (Opens box. Suddenly puts her hand to her nose.) Why — (Mrs. Peters bends nearer, then turns her face away.) There’s something wrapped up in this piece of silk.

Mrs. Peters: Why, this isn’t her scissors.

Mrs. Hale (lifting the silk): Oh, Mrs. Peters — it’s — (Mrs. Peters bends closer.)

Mrs. Peters: It’s the bird.

Mrs. Hale (jumping up): But, Mrs. Peters — look at it! Its neck! Look at its neck! It’s all — other side to.

Mrs. Peters: Somebody — wrung — its — neck. (Their eyes meet. A look of growing comprehension, of horror. Steps are heard outside. Mrs. Hale slips box under quilt pieces, and sinks into her chair. Enter Sheriff and County Attorney. Mrs. Peters rises.)

County Attorney (as one turning from serious things to little pleasantries): Well, ladies, have you decided whether she was going to quilt it or knot it?

Mrs. Peters: We think she was going to — knot it.

County Attorney: Well, that’s interesting, I’m sure. (Seeing the bird-cage.) Has the bird flown?

Mrs. Hale (putting more quilt pieces over the box): We think the — cat got it.

County Attorney (preoccupied): Is there a cat? (Mrs. Hale glances in a quick covert way at Mrs. Peters.)

Mrs. Peters: Well, not now. They’re superstitious, you know. They leave.

County Attorney (to Sheriff Peters, continuing an interrupted conversation): No sign at all of anyone having come from the outside. Their own rope. Now let’s go up again and go over it piece by piece. (They start upstairs.) It would have to have been someone who knew just the — (Mrs. Peters sits down. The two women sit there not looking at one another, but as if peering into something and at the same time holding back. When they talk now it is in the manner of feeling their way over strange ground, as if afraid of what they are saying, but as if they cannot help saying it.)

Mrs. Hale: She liked the bird. She was going to bury it in that pretty box.

Mrs. Peters (in a whisper): When I was a girl — my kitten — there was a boy took a hatchet, and before my eyes — and before I could get there — (Covers her face an instant.) If they hadn’t held me back I would have — (catches herself, looks upstairs where steps are heard, falters weakly) — hurt him.

Mrs. Hale (with a slow look around her): I wonder how it would seem never to have had any children around. (Pause.) No, Wright wouldn’t like the bird — a thing that sang. She used to sing. He killed that, too.

Mrs. Peters (moving uneasily): We don’t know who killed the bird.

Mrs. Hale: I knew John Wright.

Mrs. Peters: It was an awful thing was done in this house that night, Mrs. Hale. Killing a man while he slept, slipping a rope around his neck that choked the life out of him.

Mrs. Hale: His neck. Choked the life out of him. (Her hand goes out and rests on the bird-cage.)

Mrs. Peters (with rising voice): We don’t know who killed him. We don’t know.

Mrs. Hale (her own feeling not interrupted): If there’d been years and years of nothing, then a bird to sing to you, it would be awful — still, after the bird was still.

Mrs. Peters (something within her speaking): I know what stillness is. When we homesteaded in Dakota, and my first baby died — after he was two years old, and me with no other then —

Mrs. Hale (moving): How soon do you suppose they’ll be through looking for the evidence?

Mrs. Peters: I know what stillness is. (Pulling herself back.) The law has got to punish crime, Mrs. Hale.

Mrs. Hale (not as if answering that): I wish you’d seen Minnie Foster when she wore a white dress with blue ribbons and stood up there in the choir and sang. (A look around the room.) Oh, I wish I’d come over here once in a while! That was a crime! That was a crime! Who’s going to punish that?

Mrs. Peters (looking upstairs): We mustn’t — take on.

Mrs. Hale: I might have known she needed help! I know how things can be — for women. I tell you, it’s queer, Mrs. Peters. We live close together and we live far apart. We all go through the same things — it’s all just a different kind of the same thing. (Brushes her eyes, noticing the bottle of fruit, reaches out for it.) If I was you I wouldn’t tell her her fruit was gone. Tell her it ain’t. Tell her it’s all right. Take this in to prove it to her. She — she may never know whether it was broke or not.

Mrs. Peters (takes the bottle, looks about for something to wrap it in; takes petticoat from the clothes brought from the other room, very nervously begins winding this around the bottle. In a false voice): My, it’s a good thing the men couldn’t hear us. Wouldn’t they just laugh! Getting all stirred up over a little thing like a — dead canary. As if that could have anything to do with — with — wouldn’t they laugh! (The men are heard coming down stairs.)

Mrs. Hale (under her breath): Maybe they would — maybe they wouldn’t.

County Attorney: No, Peters, it’s all perfectly clear except a reason for doing it. But you know juries when it comes to women. If there was some definite thing. Something to show — something to make a story about — a thing that would connect up with this strange way of doing it — (The women’s eyes meet for an instant. Enter Hale from outer door.)

Hale: Well, I’ve got the team around. Pretty cold out there.

County Attorney: I’m going to stay here a while by myself. (To the Sheriff.) You can send Frank out for me, can’t you? I want to go over everything. I’m not satisfied that we can’t do better.

Sheriff: Do you want to see what Mrs. Peters is going to take in? (The Lawyer goes to the table, picks up the apron, laughs.)

County Attorney: Oh, I guess they’re not very dangerous things the ladies have picked out. (Moves a few things about, disturbing the quilt pieces which cover the box. Steps back.) No, Mrs. Peters doesn’t need supervising. For that matter a sheriff’s wife is married to the law. Ever think of it that way, Mrs. Peters?

Mrs. Peters: Not — just that way.

Sheriff (chuckling): Married to the law. (Moves toward the other room.) I just want you to come in here a minute, George. We ought to take a look at these windows.

County Attorney (scoffingly): Oh, windows!

Sheriff: We’ll be right out, Mr. Hale. (Hale goes outside. The Sheriff follows the County Attorney into the other room. Then Mrs. Hale rises, hands tight together, looking intensely at Mrs. Peters, whose eyes make a slow turn, finally meeting Mrs. Hale’s. A moment Mrs. Hale holds her, then her own eyes point the way to where the box is concealed. Suddenly Mrs. Peters throws back quilt pieces and tries to put the box in the bag she is wearing. It is too big. She opens box, starts to take bird out, cannot touch it, goes to pieces, stands there helpless. Sound of a knob turning in the other room. Mrs. Hale snatches the box and puts it in the pocket of her big coat. Enter County Attorney and Sheriff.)

County Attorney (facetiously): Well, Henry, at least we found out that she was not going to quilt it. She was going to — what is it you call it, ladies?

Mrs. Hale (her hand against her pocket): We call it — knot it, Mr. Henderson. Curtain

Considerations for Critical Thinking and Writing

- FIRST RESPONSE. Describe the setting of this play. What kind of atmosphere is established by the details in the opening scene? Does the atmosphere change through the course of the play?

- Where are Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters while Mr. Hale explains to the county attorney how the murder was discovered? How does their location suggest the relationship between the men and the women in the play?

- What kind of person was Minnie Foster before she married? How do you think her marriage affected her?

- Characterize John Wright. Why did his wife kill him?

- Why do the men fail to see the clues that Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters discover?

- What is the significance of the birdcage and the dead bird? Why do Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters respond so strongly to them? How do you respond?

- Why don’t Mrs. Hale and Mrs. Peters reveal the evidence they have uncovered? What would you have done?

- How do the men’s conversations and actions reveal their attitudes toward women?

- Why do you think Glaspell allows us only to hear about Mr. and Mrs. Wright? What is the effect of their never appearing onstage?

- Does your impression of Mrs. Wright change during the course of the play? If so, what changes it?

- What is the significance of the play’s last line, spoken by Mrs. Hale: “We call it — knot it, Mr. Henderson”? Explain what you think the tone of Mrs. Hale’s voice is when she says this line. What is she feeling? What are you feeling?

- Explain the significance of the play’s title. Do you think Trifles or “A Jury of Her Peers,” Glaspell’s title for the short story version of the play, is more appropriate? Can you think of other titles that capture the play’s central concerns?

- If possible, find a copy of “A Jury of Her Peers” online or in the library (reprinted in The Best Short Stories of 1917, ed. E. J. O’Brien [Boston: Small, Maynard, 1918], pp. 256–82), and write an essay that explores the differences between the play and the short story. (An alternative is to work with the provided excerpt.)

- CRITICAL STRATEGIES. Read the section on formalist criticism in Chapter 42, “Critical Strategies for Reading.” Several times the characters say things that they don’t mean, and this creates a discrepancy between what appears to be and what is actually true. Point to instances of irony in the play and explain how they contribute to its effects and meanings. (For discussions of irony elsewhere in this book, see the Index of Terms.)

Connections to Other Selections

- Compare and contrast how Glaspell provides background information in Trifles with how Sophocles does so in Oedipus the King.

- Write an essay comparing the views of marriage in Trifles and in Kate Chopin’s short story “The Story of an Hour.” What similarities do you find in the themes of these two works? Are there any significant differences between the works?

- In an essay compare Mrs. Wright’s motivation for committing murder with that of Matt Fowler, the central character from Andre Dubus’s short story “Killings.” To what extent do you think they are responsible for and guilty of these crimes?

Perspective

From the Short Story Version of Trifles 1917

When Martha Hale opened the storm-door and got a cut of the north wind, she ran back for her big woolen scarf. As she hurriedly wound that round her head her eye made a scandalized sweep of her kitchen. It was no ordinary thing that called her away — it was probably farther from ordinary than anything that had ever happened in Dickson County. But what her eye took in was that her kitchen was in no shape for leaving: her bread all ready for mixing, half the flour sifted and half unsifted.

She hated to see things half done; but she had been at that when the team from town stopped to get Mr. Hale, and then the sheriff came running in to say his wife wished Mrs. Hale would come too — adding, with a grin, that he guessed she was getting scarey and wanted another woman along. So she had dropped everything right where it was.

“Martha!” now came her husband’s impatient voice. “Don’t keep folks waiting out here in the cold.”

She again opened the storm-door, and this time joined the three men and the one woman waiting for her in the big two-seated buggy.

After she had the robes tucked around her she took another look at the woman who sat beside her on the back seat. She had met Mrs. Peters the year before at the county fair, and the thing she remembered about her was that she didn’t seem like a sheriff’s wife. She was small and thin and didn’t have a strong voice. Mrs. Gorman, sheriff’s wife before Gorman went out and Peters came in, had a voice that somehow seemed to be backing up the law with every word. But if Mrs. Peters didn’t look like a sheriff’s wife, Peters made it up in looking like a sheriff. He was to a dot the kind of man who could get himself elected sheriff — a heavy man with a big voice, who was particularly genial with the law-abiding, as if to make it plain that he knew the difference between criminals and noncriminals. And right there it came into Mrs. Hale’s mind, with a stab, that this man who was so pleasant and lively with all of them was going to the Wrights’ now as a sheriff.

“The country’s not very pleasant this time of year,” Mrs. Peters at last ventured, as if she felt they ought to be talking as well as the men.

Mrs. Hale scarcely finished her reply, for they had gone up a little hill and could see the Wright place now, and seeing it did not make her feel like talking. It looked very lonesome this cold March morning. It had always been a lonesome-looking place. It was down in a hollow, and the poplar trees around it were lonesome-looking trees. The men were looking at it and talking about what had happened. The county attorney was bending to one side of the buggy, and kept looking steadily at the place as they drew up to it.

“I’m glad you came with me,” Mrs. Peters said nervously, as the two women were about to follow the men in through the kitchen door.

Even after she had her foot on the door-step, her hand on the knob, Martha Hale had a moment of feeling she could not cross that threshold. And the reason it seemed she couldn’t cross it now was simply because she hadn’t crossed it before. Time and time again it had been in her mind, “I ought to go over and see Minnie Foster” — she still thought of her as Minnie Foster, though for twenty years she had been Mrs. Wright. And then there was always something to do and Minnie Foster would go from her mind. But now she could come.

The men went over to the stove. The women stood close together by the door. Young Henderson, the county attorney, turned around and said, “Come up to the fire, ladies.”

Mrs. Peters took a step forward, then stopped. “I’m not — cold,” she said.

And so the two women stood by the door, at first not even so much as looking around the kitchen.

The men talked for a minute about what a good thing it was the sheriff had sent his deputy out that morning to make a fire for them, and then Sheriff Peters stepped back from the stove, unbuttoned his outer coat, and leaned his hands on the kitchen table in a way that seemed to mark the beginning of official business. “Now, Mr. Hale,” he said in a sort of semiofficial voice, “before we move things about, you tell Mr. Henderson just what it was you saw when you came here yesterday morning.”

The county attorney was looking around the kitchen.

“By the way,” he said, “has anything been moved?” He turned to the sheriff. “Are things just as you left them yesterday?”

Peters looked from cupboard to sink; from that to a small worn rocker a little to one side of the kitchen table.

“It’s just the same.”

“Somebody should have been left here yesterday,” said the county attorney.

“Oh — yesterday,” returned the sheriff, with a little gesture as of yesterday having been more than he could bear to think of. “When I had to send Frank to Morris Center for that man who went crazy — let me tell you, I had my hands full yesterday. I knew you could get back from Omaha by to-day, George, and as long as I went over everything here myself —”

“Well, Mr. Hale,” said the county attorney, in a way of letting what was past and gone go, “tell just what happened when you came here yesterday morning.”

Mrs. Hale, still leaning against the door, had that sinking feeling of the mother whose child is about to speak a piece. Lewis often wandered along and got things mixed up in a story. She hoped he would tell this straight and plain, and not say unnecessary things that would just make things harder for Minnie Foster. He didn’t begin at once, and she noticed that he looked queer — as if standing in that kitchen and having to tell what he had seen there yesterday morning made him almost sick.

“Yes, Mr. Hale?” the county attorney reminded.

“Harry and I had started to town with a load of potatoes,” Mrs. Hale’s husband began.

Harry was Mrs. Hale’s oldest boy. He wasn’t with them now, for the very good reason that those potatoes never got to town yesterday and he was taking them this morning, so he hadn’t been home when the sheriff stopped to say he wanted Mr. Hale to come over to the Wright place and tell the county attorney his story there, where he could point it all out. With all Mrs. Hale’s other emotions came the fear that maybe Harry wasn’t dressed warm enough — they hadn’t any of them realized how that north wind did bite.

“We come along this road,” Hale was going on, with a motion of his hand to the road over which they had just come, “and as we got in sight of the house I says to Harry, ‘I’m goin’ to see if I can’t get John Wright to take a telephone.’ You see,” he explained to Henderson, “unless I can get somebody to go in with me they won’t come out this branch road except for a price I can’t pay. I’d spoke to Wright about it once before; but he put me off, saying folks talked too much anyway, and all he asked was peace and quiet — guess you know about how much he talked himself. But I thought maybe if I went to the house and talked about it before his wife, and said all the women-folks liked the telephones, and that in this lonesome stretch of road it would be a good thing — well, I said to Harry that that was what I was going to say — though I said at the same time that I didn’t know as what his wife wanted made much difference to John —”

Now, there he was! — saying things he didn’t need to say. Mrs. Hale tried to catch her husband’s eye, but fortunately the county attorney interrupted with:

“Let’s talk about that a little later, Mr. Hale. I do want to talk about that, but I’m anxious now to get along to just what happened when you got here.”

From “A Jury of Her Peers”

Considerations for Critical Thinking and Writing

- In this opening scene from the story, how is the setting established differently from the way it is in the play, Trifles?

- What kind of information is provided in the opening paragraphs of the story that is missing from the play’s initial scene? What is emphasized early in the story but not in the play?

- Which version brings us into more intimate contact with the characters? How is that achieved?

- Does the short story’s title, “A Jury of Her Peers,” suggest any shift in emphasis from the play’s title, Trifles?

- Explain why you prefer one version over the other.