ADAM, SETH, ENOSH, 2Kenan, Mahalalel, Jared, 3Enoch, Methuselah, Lamech, Noah.

4The sons of Noah:

Shem, Ham and Japheth.

5The sons of Japheth:

Gomer, Magog, Madai, Javan, Tubal, Meshech and Tiras.

6The sons of Gomer:

Ashkenaz, Riphath and Togarmah.

7The sons of Javan:

Elishah, Tarshish, the Kittim and the Rodanim.

8The sons of Ham:

Cush, Mizraim, Put and Canaan.

9The sons of Cush:

Seba, Havilah, Sabta, Raamah and Sabteca.

The sons of Raamah:

Sheba and Dedan.

10Cush was the father of

Nimrod, who grew to be a mighty warrior on earth.

11Mizraim was the father of

the Ludites, Anamites, Lehabites, Naphtuhites,

12Pathrusites, Casluhites (from whom the Philistines came) and Caphtorites.

13Canaan was the father of

Sidon his firstborn, and of the Hittites, 14Jebusites, Amorites, Girgashites, 15Hivites, Arkites, Sinites,

16Arvadites, Zemarites and Hamathites.

17The sons of Shem:

Elam, Asshur, Arphaxad, Lud and Aram.

The sons of Aram:

Uz, Hul, Gether and Meshech.

18Arphaxad was the father of Shelah,

and Shelah the father of Eber.

19Two sons were born to Eber:

One was named Peleg, because in his time the earth was divided; his brother was named Joktan.

Almodad, Sheleph, Hazarmaveth, Jerah, 21Hadoram,

Uzal, Diklah, 22Obal, Abimael, Sheba, 23Ophir, Havilah

and Jobab. All these were sons of Joktan.

24Shem, Arphaxad, Shelah,

25Eber, Peleg, Reu,

26Serug, Nahor, Terah

27and Abram (that is, Abraham).

28The sons of Abraham:

Isaac and Ishmael.

29These were their descendants:

Nebaioth the firstborn of Ishmael, Kedar, Adbeel, Mibsam, 30Mishma, Dumah, Massa, Hadad, Tema, 31Jetur, Naphish and Kedemah. These were the sons of Ishmael.

32The sons born to Keturah, Abraham’s concubine:

Zimran, Jokshan, Medan, Midian, Ishbak and Shuah.

The sons of Jokshan:

Sheba and Dedan.

33The sons of Midian:

Ephah, Epher, Hanoch, Abida and Eldaah.

All these were descendants of Keturah.

34Abraham was the father of Isaac.

The sons of Isaac:

Esau and Israel.

35The sons of Esau:

Eliphaz, Reuel, Jeush, Jalam and Korah.

36The sons of Eliphaz:

Teman, Omar, Zepho, Gatam and Kenaz; by Timna: Amalek.

37The sons of Reuel:

Nahath, Zerah, Shammah and Mizzah.

38The sons of Seir:

Lotan, Shobal, Zibeon, Anah, Dishon, Ezer and Dishan.

39The sons of Lotan:

Hori and Homam. Timna was Lotan’s sister.

40The sons of Shobal:

Alvan, Manahath, Ebal, Shepho and Onam.

The sons of Zibeon:

Aiah and Anah.

41The son of Anah:

Dishon.

Hemdan, Eshban, Ithran and Keran.

42The sons of Ezer:

Bilhan, Zaavan and Akan.

The sons of Dishan:

Uz and Aran.

43These were the kings who reigned in Edom before any Israelite king reigned:

Bela son of Beor, whose city was named Dinhabah.

44When Bela died, Jobab son of Zerah from Bozrah succeeded him as king.

45When Jobab died, Husham from the land of the Temanites succeeded him as king.

46When Husham died, Hadad son of Bedad, who defeated Midian in the country of Moab, succeeded him as king. His city was named Avith.

47When Hadad died, Samlah from Masrekah succeeded him as king.

48When Samlah died, Shaul from Rehoboth on the river succeeded him as king.

49When Shaul died, Baal-Hanan son of Acbor succeeded him as king.

50When Baal-Hanan died, Hadad succeeded him as king. His city was named Pau, and his wife’s name was Mehetabel daughter of Matred, the daughter of Me-Zahab. 51Hadad also died.

The chiefs of Edom were:

Timna, Alvah, Jetheth, 52Oholibamah, Elah, Pinon, 53Kenaz, Teman, Mibzar, 54Magdiel and Iram. These were the chiefs of Edom.

2:1These were the sons of Israel:

Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, 2Dan, Joseph, Benjamin, Naphtali, Gad and Asher.

Original Meaning

BIBLICAL SCHOLARS HAVE long noted that the genealogies of the prologue to Chronicles (1 Chron. 1–9) are a mini-commentary of sorts on the book of Genesis. This understanding is largely based on the phrase “these are the generations of,” which provides a structural framework for the narratives of Genesis (e.g., Gen. 5:1; 10:1 RSV). In most cases, the Chronicler borrows from earlier genealogical sources and pares the listings to a register of names only (e.g., Gen. 5:1–32; cf. 1 Chron. 1:1–4). God is everywhere assumed but nowhere mentioned in genealogies. The Chronicler also takes it for granted that his audience knows well the stories and personalities associated with the names logged in the genealogies. This fact is important to understanding the rest of the Chronicles as well. The highly selective retelling of Israel’s history presupposes the Chronicler’s audience knows their Hebrew Bible.

Selman has noted that the pivot points of the introductory genealogy are names of great significance in the early history of God’s people, including Adam (1:1), Noah (1:4), Abraham (1:27, 28, 32, 34), and Israel (or Jacob, 1:34; 2:1). Further, he has observed that each section of the genealogy is arranged in such a way that the person providing the link from Adam to Israel is mentioned last in each generation.1 This means that the sequence of names does not always correspond with birth order as presented in the Genesis narratives.

More important are the theological threads unifying this opening genealogy. (1) The nations are introduced in such a way that all peoples are placed inside rather than outside the purposes of God’s electing love. (2) The nation of Israel lies at the center of the genealogical scheme. Thus, the Israel of the Chronicler’s day is united with the earlier Israel and with the nations.

The genealogical prologue found in 1 Chronicles 1–9 contains the most extensive and complex genealogies of the Bible. According to Robert Wilson, “a genealogy is a written or oral expression of the descent of a person or persons from an ancestor or ancestors.”2 Particular terminology is sometimes used to characterize the composition of biblical genealogies, such as:

• breadth, a listing of a single generation of descendants from a common ancestor (e.g., 2:1)

• depth, a listing of successive generations, commonly four to six (e.g., 3:10–16)

• linear, displaying depth alone (e.g., 2:10)

• segmented, displaying both breadth and depth (e.g., 3:17–24)

• descending, or proceeding from parent to child (e.g., 9:39–44)

• ascending, or moving from child to parent (e.g., 9:14–16)3

The basic purpose of the genealogy is to identify kinship relationships between individuals, families, and people groups. Marshall Johnson has isolated nine distinct functions that genealogies serve in the Old Testament:

• demonstrate existing relationships between Israel and neighboring tribes by establishing common ancestors (e.g., the relationship of Lot’s descendants to Israel, Gen. 19:36–38)

• connecting isolated traditions of Israelite origins into a coherent literary unit by means of an inclusive genealogical system (e.g., the toledot formulas in Genesis [5:1; 10:1; etc.])

• bridge chronological gaps in the biblical narratives (e.g., Ruth 4:18–22)

• serve as chronological controls for the dating of key Old Testament events (e.g., the date of the book of Esther in relationship to the Babylonian exile, Est. 2:5–6—although the selective nature of biblical genealogies may compromise the accuracy of the genealogy as a chronological device)

• perform a specific political and/or military function, as in the taking of a census (e.g., Num. 1:3–46)

• legitimize an individual or family in an office or enhance the stature of an individual by linkage to an important clan or individual of the past (e.g., Zeph. 1:1)

• establish and preserve the ethnic purity of the Hebrew community, as in the case of the records found in Ezra and Nehemiah (e.g., Ezra 7)

• assert the importance of the continuity of God’s people through a period of national calamity (prominent in Chronicles, e.g., the line of David in 1 Chron. 3:17–24)

• express order, structure, and movement in history according to a divinely prearranged plan (e.g., identifying Haman, the son of Hammedatha, as an Agagite, Est. 3:1, 10).4

It is evident the genealogies of 1 Chronicles 1–9 serve multiple purposes, especially in legitimizing the authority of Levitical priesthood as the rightful successors to the royal authority of Davidic kingship and in asserting the continuity of the Hebrew people through the national distress of the Babylonian exile. There is even a sense in which the juxtaposition of certain genealogies (e.g., that of Esau and Israel or Saul and David) works to express movement in history according to God’s redemptive plan.

A child was named immediately upon birth during Old Testament times, and the name was usually chosen by the mother (e.g., Gen. 35:18; 1 Sam. 1:20).5 The ancients understood the name to signify the essence of a thing or a person. The naming process involved knowledge of the thing or person named and power over that entity once the name was ascribed (e.g., Pharaoh’s naming Joseph as Zaphenath-Paneah, Gen. 41:45).

Since the name denoted essential being, a child’s name was chosen with great care. A person’s name revealed the character and personality as well as the reputation, authority, vocation, and even the destiny of the bearer. At times unusual circumstances surrounding the birth inspired a child’s name (e.g., Isaac, Gen. 21:6–7; Samuel, 1 Sam. 1:20). On occasion the shifting fortunes in a person’s life situation or the transformation of a person’s character prompted a name change (e.g., Jacob becomes Israel, Gen. 32:28; Naomi becomes Mara, Ruth 1:20).

Many Old Testament names are theophoric; that is, they contain some element of a divine name or title indicating one’s religious loyalty (e.g., Josiah [= “Yahweh will give”], 1 Chron. 3:14; Elkanah [= “God has created”], 1 Chron. 6:23; Merib-Baal [“the Lord/Baal contends”], 1 Chron. 8:34). All this is a part of the worldview of the Chronicler’s audience. The genealogy is not simply a catalog of the names of dead ancestors. Rather, it represents a rich history of family, clan, and nation told and retold through the life and story represented by the personal names of individuals who form an integral part of the larger story of the Israelite community.

The Chronicler’s panoramic sweep of ancient history from Adam to Noah to Abraham and Israel transports the audience into the accounts of the book of Genesis. There the emphasis was on God’s dealings with humanity both in terms of creation and redemption. The same is true for the Chronicler, especially as he traces the names of key players in the unfolding drama of God’s redemptive plan for humanity. The stories behind the names in the genealogies may hint at themes and ideas important to the Chronicler. For example, Enoch “walked” with God (1 Chron. 1:3; cf. Gen. 5:24), a repeated phrase in the Chronicler’s evaluation of the kings of Judah (e.g., 2 Chron. 17:3; 21:12; etc.). Perhaps Nimrod the “mighty warrior” (1 Chron. 1:10; cf. Gen. 10:8–9) inspires the descriptions of the mighty warriors of David’s day (e.g., 1 Chron. 12:8, 21, 28, etc.).

The reference to Noah, his sons, and their descendants further develops the links between the Chronicler’s genealogical prologue and the Genesis narratives (1 Chron. 1:4–27). The proliferation of people (groups) registered under the names of Japheth, Ham, and Shem calls to mind the creation mandate to populate the earth (Gen. 1:28) and later echoed to those survivors of the great Flood (Gen. 9:7). The genealogy of Noah also functions to introduce Abraham through the line of Shem (1 Chron. 1:17, 27).

Equally important are the great theological themes the story of Noah establishes, themes that course through the rest of the Bible—especially the covenant relationship with God (Gen. 9:11) and the twin truths of God’s judgment of human sin and rebellion and his sustaining grace in preserving the righteous (Gen. 6:7–8).

In terms of recorded material, Abraham (1 Chron. 1:28–33) receives less attention in the opening genealogy than does Esau and Seir (1:34–54). Nonetheless, the family of Abraham is located strategically in the middle of the listing of names from Adam (1:1) to Israel (2:1) and appropriately paired with the family of Esau as a foil, illustrating contrasting responses to covenant relationship with Yahweh. If we keep in mind the stories represented by the names, in one sense the genealogy of Abraham is flanked by destruction: Noah and the Flood at the front end and Esau and the eventual obliteration of the Edomites on the other.

Not coincidentally, the listing of the twelve sons of Israel follows the genealogy of Esau, a reminder that the Hebrews persist as the people of God. Although the Chronicler gives Abraham prominence as the father of the Israelites, the genealogy has included all the descendants of Abraham as confirmation of God’s fulfillment of the promise to make Abraham the father of many nations (cf. Gen. 17:3–6). Interestingly, the genealogy of Abraham mentions Keturah, the concubine of Abraham (1 Chron. 1:32; v. 28 assumes knowledge of Hagar and Sarah as wives of Abraham). The citation is unusual in that Old Testament genealogies primarily document family history from male descendant to male descendant without reference to mothers. Theologically, however, this name and the other names of women in the Chronicler’s genealogies may be a subtle reference to their role in the “offspring of the woman” theology for restoring humanity to Eden (Gen. 3:15–16). This theme is continued in both Kings and Chronicles, as the mothers of the Judahite kings (only) are recorded in accession formulas.

The genealogies of Esau and Edom combine four separate catalogs, each with Esau as the common element (1 Chron. 1:35–54). The list of Esau’s descendants (vv. 35–37; cf. Gen. 36:10–14) is followed by that of Seir, ancient neighbors of the Edomites and ancestors of the Horites (vv. 38–42; cf. Gen. 14:6; 36:20–28; Deut. 2:12, 22). The record of Edomite rulers (1 Chron. 1:43–54; cf. Gen. 36:31–43) attests the prominence of that nation in Old Testament history (cf. Num. 20:14–21; Jer. 49:7–22). Indeed, the legacy of the Edomites was entwined with Israel from the birth of Esau (Gen. 25:23–26) to the ruin of Edom during the early postexilic period for aiding and abetting the Babylonians in the sack of Jerusalem (cf. Ps. 137:7).

The extensive register of names demonstrates that Esau has multiplied, but “that was as nothing compared to the miracle that God had worked for his brother’s family.”6 The repetition of the fact that each Edomite king “died” is significant as well. The Edomite kings died, and in one sense so did the nation of Edom, as it was destroyed or absorbed by the Nabatean Arabs (sometime between 550 and 400 B.C.). The kings of Judah died as well, but the people of Israel survived the collapse of Davidic kingship, returned to Jerusalem, and rebuilt the city. The Chronicler’s juxtaposition of Esau’s and Israel’s genealogies may be an allusion to the prophet Malachi’s assessment of the twins with respect to covenant relationship with God: “I have loved [chosen] Jacob, but Esau I have hated [rejected]” (Mal. 1:2–3).

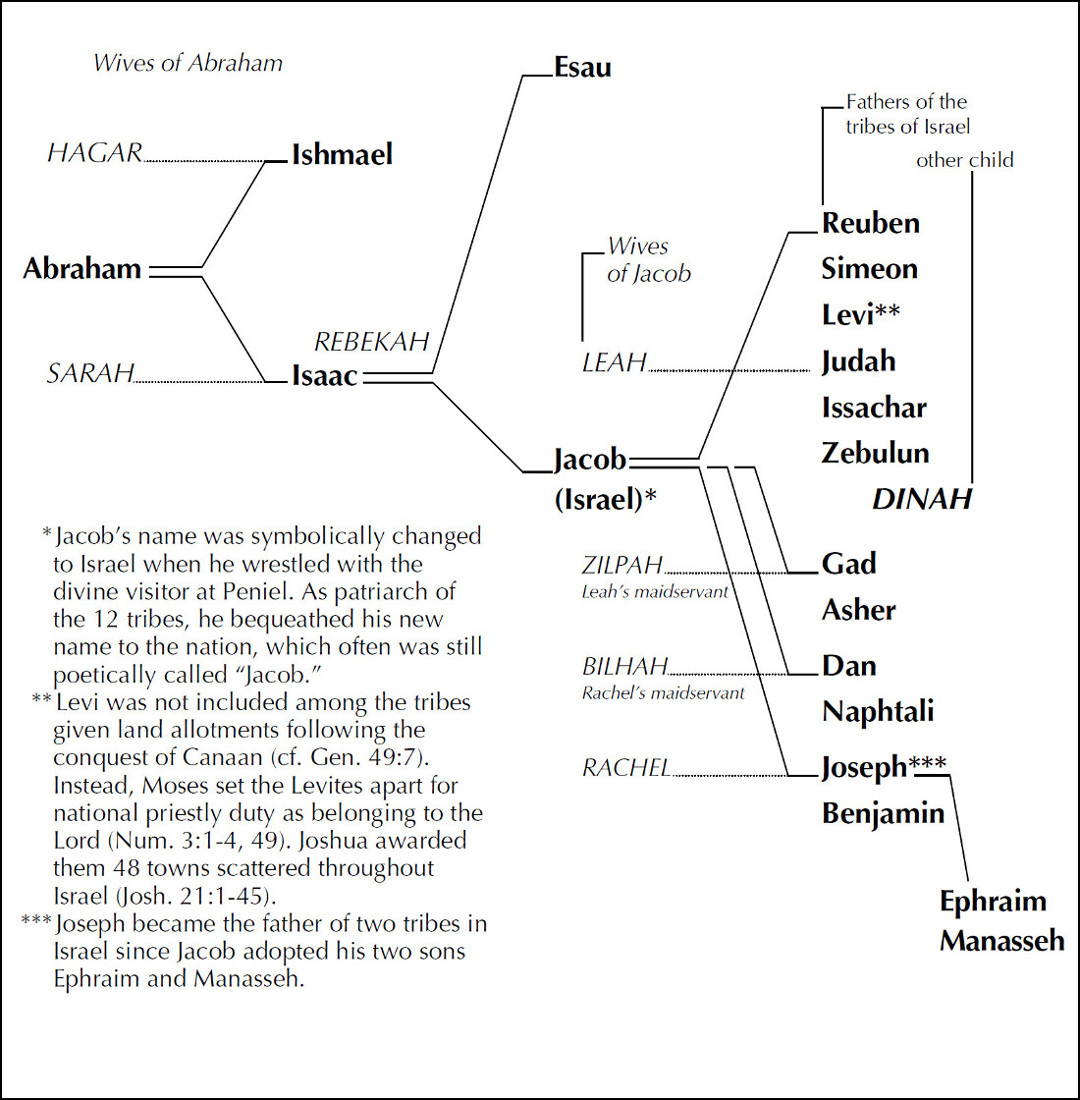

The final passage of the section simply lists the twelve sons of Jacob, later named Israel (Gen. 32:28; see chart below). The Chronicler only uses the name “Israel” for the patriarch in the retelling of his history of God’s people. Since a change of name in the Old Testament often indicates a change in one’s character or station in life, it may be that the Chronicler suggests the same for the remnant of the Israelites after the Exile.

Like Jacob, they too have experienced a transformation in that the Babylonian exile has cured God’s people of the sin of idolatry. The catalog of the twelve sons of Israel sets the stage for the remainder of the genealogies comprising the prologue of Chronicles. Both Zebulun and Dan are slighted by the Chronicler, and Naphtali’s descendants are mentioned in a single verse (7:13). This selectivity in the presentation of the genealogical records further underscores the Chronicler’s pointed interests in the lineage of Judah and the institution of kingship and the lineage of Levi and the office of the priesthood.

Bridging Contexts

THE GENEALOGIES OF 1 Chronicles 1–9 suggest an important point of transition between the Chronicler’s context and our own related to the psychosocial conflict known as an “identity crisis.”7 According to Erikson, “identity” may refer to the sense of sameness or continuity between one’s past and present selves, the integration of one’s private and public selves, or the relationship between one’s present self and one’s future self.8 In a nondiagnostic sense, an identity crisis may be described as a personal sense of confusion about one’s defining characteristics and social role. On the individual level this confusion may involve a loss of continuity with one’s basic personality traits or some form of disconnection with one of the distinctive selves of personhood (e.g., the private self with the public self). The nation addressed by the Chronicler demonstrates a “collective identity,” especially with respect to the notion of continuity or sameness between past, present, and future “self.” At the corporate level, then, an identity crisis may signify the dislocation of an entity from the constituting principles outlined in its original charter.

Fig. 4. The Tribes of Israel

The Chronicler’s audience is plagued by such a crisis. Israel’s “identity” both in terms of a crucial defining characteristic and consequent social role had been associated with Davidic kingship for several centuries. The Babylonian exile and its aftermath has disrupted Israelite continuity with this basic “personality trait” and resulted in a state of national confusion concerning the identity of the Jews as the people of God.

All Israelites were keenly aware of the several important elements contained in their constituting charter or covenant, especially the divine promise about perpetual Davidic kingship and the central role of Israel among the nations (2 Sam. 7:5–16). Neither are true for the Jews at the time of the Chronicler’s writing. The symptoms of this identity crisis in postexilic Israel are evidenced in numerous ways, including the abandonment of corporate religious ideals for personal comforts (cf. Neh. 13:15–18; Hag. 1:3–11) and the spirit of malaise that characterizes the Israelite approach to other basic principles of their covenantal charter, such as tithing, social justice, and interracial marriage (cf. Ezra 9:1–2; Neh. 5:1–11; Mal. 3:5–9).

According to McConville, the basic function of the biblical genealogy is to demonstrate that the divine promises and purposes are still operative in God’s overall plan.9 The Chronicler counters the identity crisis in postexilic Israel, in part, by appealing to the genealogical history of the Jews. The recitation of the ancient genealogies serves to build historical and theological connections between postexilic Israel and her earliest ancestors, reestablishing the continuity of the later community with the true “people of God.” The links to Adam and Noah affirm the realization of the divine purposes related to the creation mandate for filling the earth and ruling over it (Gen. 1:26–28). Likewise, the ligature to Abraham and Israel (i.e., Jacob) assures the postexilic Jewish community that they are the heirs of the covenant promises of God made to the patriarchs and matriarchs of Israel (Gen. 12:1–3; 17:3–14; 26:3–4; etc.).

Theologically for the Chronicler, the issue is the continuity of Yahweh’s kingship over creation and all the nations, not merely Davidic kingship in Israel. For this reason, he frames the retelling of the history of Israel between the genealogy excerpted from the Table of Nations (1 Chron. 1; cf. Gen. 10) and the decree of King Cyrus of Persia (2 Chron. 36:22–23). The “nations” serve as the bookends for the story of kingship in Israel, indicating that they too stand inside the unfolding plan of God’s redemption of fallen creation. In addition, Israel’s role as the “elect of God” remains secure in the reality of God’s sovereignty over all the peoples of the earth. God has chosen one nation so he might bless all nations. The opening genealogy of Chronicles is a simple reminder of that fact. Israel’s identity crisis during the postexilic period is primarily a matter of poor theology, not bad psychology.

Ultimately, the Chronicler’s recitation of genealogies is a lesson in God’s faithfulness to the word of his covenant promise. Israel’s worth and dignity, her “identity” so to speak, lies outside the changing circumstances of history and in the character and plan of God Almighty. This truth sets the stage for one of the key themes of the books of Chronicles, the proper worship of Yahweh as the Lord of creation, the Sovereign of the nations, and the God of Israel.

Contemporary Significance

IDENTITY CONFUSION. The identity crisis in postexilic Judah was only secondarily a matter of historical circumstance. Granted, Davidic kingship no longer defined Israel, and the Persian Empire still controlled the fate of the Jewish people. Yet the real crisis in postexilic Judah was one of theological understanding. The Chronicler’s generation had misinterpreted the message of the earlier prophets concerning the nature and the timing of the restoration of Israel. This misunderstanding of God’s revelation for the future of Israel led to a distorted perception of the current situation confronting God’s people. Like the first generation of expatriates who returned from Babylonia, they had expected much but had experienced little (Hag. 1:9). Naturally, blame was displaced away from unkept individual or corporate covenant responsibilities and onto God and his failure to make good on the word of his promises (cf. Hag. 1:4; Zech. 7:5–7; Mal. 3:14).

Specifically, the several generations of Jews from the time of Haggai and Zerubbabel to the Chronicler had been expecting the reinstatement of Davidic kingship and the restoration of national Israel (cf. Hag. 2:20–22). Clearly this is what Jeremiah and Ezekiel predicted after the return from Babylonian captivity (cf. Jer. 33:15–22; Ezek. 34:20–25). Later, the prophets Zechariah and Malachi essentially told their constituencies to “hang in there,” for God would soon inaugurate the new Davidic kingdom and restore the fortunes of Israel (i.e., “the day is coming”; cf. Zech. 12:10; 13:1; Mal. 3:1; 4:1). But by the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, there is no longer any mention of a Davidic king or a restored Hebrew nation. The postexilic community has resigned itself to hierocratic or priestly rule as well as economic and political subordination in the vast Persian Empire.

Whether verbalized or not, the Chronicler’s audience suspects that God’s word has failed.10 All this suggests that the identity crisis in postexilic Judah is surely one of compounded disenfranchisement—both in a psychological rootlessness, fostering insecurity and alienation (since the “present self” of the Hebrew nation is divorced from its “past self” as an autonomous monarch), and in a theological discontinuity, resulting in apathy and despair (since the “present self” of the Hebrew nation has lost any hope of actualizing the prophetic word that promised the restoration of the “future self” of Israel).

The Chronicler’s response to this identity crisis proves valuable as a model for the contemporary reader of the Bible. The context of his message parallels that of modern society, given the religious pluralism, ethnic diversity, and philosophical relativism that characterized the sprawling Persian Empire. Likewise, human nature is a constant since we are prone to the same syndrome of “victimization” evident in the behavior of our earliest ancestors (e.g., Adam was a “victim” of the woman’s hasty impulse and Eve was a “victim” of the serpent’s smooth talk; cf. Gen. 3:12–13).11

Furthermore, the prophets from Moses to Jesus recognized that the Word of God was susceptible to human manipulation and warned against exchanging divine truth for human traditions (cf. Deut. 13:3; 16:19; Mark 7:8–9). Finally, an important part of the Christian message promulgated by the church during the interim between the advents of Christ is that of “waiting” for the return of God’s Son from heaven (1 Thess. 1:9–10; cf. 2 Peter 3:4). Thus, we see that in certain respects the ancient and the modern worlds are not all that different. What then might we learn from the Chronicler as we encounter and respond to the “identity crises” besetting the people of God today?

Before developing a biblical template for countering human crises based on the example of the Chronicler’s strategy, it may be helpful to recall our definition of this psychological conflict. Previously, we explained an identity crisis as a personal or collective sense of confusion about one’s defining characteristics and social role. Such confusion may be individual in nature, as seen in the agony of Jeremiah’s conflict with ideals of the prophetic office and the reality of the human response to the divinely prompted message (cf. Jer. 20:7–18). Thus, for the individual this identity confusion may result in the loss of continuity with the basic traits of one’s self or personhood (e.g., the “persecution” paranoia eroding Jeremiah’s self-esteem [Jer. 20:7–10] and his “death-wish” conflicting with his will for self-preservation [20:14–18]).

Or such confusion may be experienced in a corporate manner, as in the case of Israel’s penchant for the idolatry and immorality of the Baal cult in flagrant violation of the stipulations of the Mosaic covenant (e.g., Hos. 4:16–18; Amos 2:4–5). At the collective level this identity confusion may signify the dislocation of an entity or a nation from the constituting principles outlined in its original charter (e.g., the radical monotheism prescribed for worship in the Sinai covenant in opposition to the polytheism characteristic of the ancient world). In either case, the Chronicler offers the contemporary reader helpful guidelines for resolving those conflicts.

(1) Approach the crisis directly. One of the defining characteristics of ancient Israel was Davidic kingship. The idolatry of God’s people eventually led to the Babylonian exile and the loss of the foundational institutions of Israelite life—the monarchy and the temple. Upon their return from the Babylonian captivity, the Persians permitted the restoration of the temple only. The horrific trauma and the nightmarish aftermath of the Exile (memorialized in the book of Lamentations) evoked the identity crisis in postexilic Judah.

The Chronicler employs a two-pronged approach to the theme of the Davidic dynasty, including both genealogical recitation (emphasizing the tribes of Judah and Levi) and historical review (focusing primarily on the Judahite monarchy). His direct approach affirms the importance of the issue for the restoration community. In so doing he acknowledges that the crisis is real and establishes a bond of empathy with his audience. This in turn lends a sense of credibility and genuineness to his message and makes the transition to an alternative form of community governance (i.e., priestly authority instead of royal authority) a more bearable experience for the people.

(2) Isolate the cause rather than treat the symptoms of the crisis. Earlier we characterized Chronicles as a “theology of hope” for the beleaguered Jews residing in postexilic Jerusalem. The writer, however, does not attempt to manipulate emotions by inducing guilt or raising false expectations. Nor does he seek to motivate or inspire the people by means of self-help “pop psychology.” Rather, he encourages his audience with sound doctrine in the form of a biography of God, emphasizing his sovereign rule as Creator, his providential intervention as Sustainer, and his unconditional election of Israel (see Introduction, “Chronicles As a Biography of God”). Ultimately, human crises are theological in nature in that they are generally related to the idea of theodicy (or the problem of evil in relationship to the goodness of God). The psalmist recognized that intimate knowledge and proper worship of God are essential for gaining some perspective on the “crookedness” of life in a fallen world (Ps. 73:16–17, 26, 28).

The Chronicler is well aware of this biblical truism, so he too steers his audience to the person and character of God for an explanation of and a solution to their crisis. The New Testament is consistent with the Old Testament pattern as the apostle Paul coached Titus to “encourage others” by teaching sound doctrine (Titus 1:9).

(3) Locate the crisis within a larger historical and theological framework, a metanarrative. Walsh and Middleton regard a metanarrative as a grounding or legitimating “story” (i.e., a narrative or tradition) that shapes the worldview and guides the practice of a given community.12 A metanarrative possesses a “mythic” quality that accounts for a given way of life and that is taken as the normative expression for that way of life. The concept of metanarrative is under attack in our postmodern society. We see a pervasive incredulity toward metanarratives because given the current emphasis on pluralism and diversity in North American culture, no metanarrative is comprehensive enough to include the experiences and realities of all people.13

The Chronicler uses the literary form of the genealogy to locate postexilic Judah in a larger historical framework—a metanarrative. By definition, an identity crisis is rooted in the self, whether the personality of an individual or a particular social group. The metanarrative functions to divert attention away from “self” to those common ideas and experiences shared by all people for all time. By resorting to the genealogy, the Chronicler is able to move his audience off “center,” so to speak—off self-pity and narcissistic introspection. Perspective and insight on the present are gained when an acute problem is situated in a larger context. The loss of Davidic kingship in post-exilic Judah pales in comparison to the loss of Edenic fellowship with God when David, Judah, and Israel are placed in a metanarrative that includes Adam and Noah. The “story” of postexilic Judah is hardly unique when viewed against the “story” of humanity.14

(4) Link the metanarrative to the work and words of God. It is not enough to locate any given human predicament in a larger historical context. The metanarrative must have a substantial theological orientation as well. Only then will it possess an intrinsic authority that supersedes the rival claims of some remarkable personal experience or the long-standing tradition of any social group. Only then will the “legitimating story” exhibit a moral universality that is inherently just and practically feasible. Only this kind of metanarrative is comprehensive enough to embrace, order, and explain the unity and diversity of all creation.

For the Chronicler, the theological locus of the biblical metanarrative is the God of Israel. Especially important to the formation of the theological baseline for his metanarrative are the words of God emphasizing divine promise and fulfillment. The Davidic covenant (1 Chron. 17:3–14) and God’s response to Solomon’s prayer of dedication after completing the temple are strategic examples (2 Chron. 7:11–22). Granted, important theological ideas are only implicitly represented in the personal stories of the names cited in the genealogical records. They become explicit, however, in the Chronicler’s highly selective recital of Israelite history. This is especially the case in his depiction of God in the numerous prayers scattered throughout the accounts of the kings of Judah (e.g., 1 Chron. 29:10–13; 2 Chron. 20:6–12).

The Chronicler’s theology of hope is credible for the Jewish restoration community because the God of Israel has proven faithful to his Word across the generations from Adam to all those listed in his genealogy—the prominent and the obscure. Perhaps more important, the great deeds of God including the work of creation, the Exodus from Egypt, and most recently the prompting of Cyrus king of Persia to rebuild the temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem are now documented and inscripturated (2 Chron. 36:22–23). Thus the Chronicler’s metanarrative has the currency of canonical status in the Jewish community.

By appealing to those books and records already a part of the Hebrew Bible as resources for his preaching and teaching, the Chronicler offers his audience the flawless, true, and eternal Word of God himself (Ps. 18:30; 33:4; Isa. 40:8). Such is the pattern for apostolic preaching in the New Testament (cf. Acts 2; 7; 13; 15), and so it remains for preaching and teaching in the church today. The unfolding drama of God’s redemption of humanity as recorded in Scripture continues to provide the legitimate metanarrative for the Christian faith (2 Tim. 3:15–16).