DAVID CONFERRED WITH each of his officers, the commanders of thousands and commanders of hundreds. 2He then said to the whole assembly of Israel, “If it seems good to you and if it is the will of the LORD our God, let us send word far and wide to the rest of our brothers throughout the territories of Israel, and also to the priests and Levites who are with them in their towns and pasturelands, to come and join us. 3Let us bring the ark of our God back to us, for we did not inquire of it during the reign of Saul.” 4The whole assembly agreed to do this, because it seemed right to all the people.

5So David assembled all the Israelites, from the Shihor River in Egypt to Lebo Hamath, to bring the ark of God from Kiriath Jearim. 6David and all the Israelites with him went to Baalah of Judah (Kiriath Jearim) to bring up from there the ark of God the LORD, who is enthroned between the cherubim—the ark that is called by the Name.

7They moved the ark of God from Abinadab’s house on a new cart, with Uzzah and Ahio guiding it. 8David and all the Israelites were celebrating with all their might before God, with songs and with harps, lyres, tambourines, cymbals and trumpets.

9When they came to the threshing floor of Kidon, Uzzah reached out his hand to steady the ark, because the oxen stumbled. 10The LORD’s anger burned against Uzzah, and he struck him down because he had put his hand on the ark. So he died there before God.

11Then David was angry because the LORD’s wrath had broken out against Uzzah, and to this day that place is called Perez Uzzah.

12David was afraid of God that day and asked, “How can I ever bring the ark of God to me?” 13He did not take the ark to be with him in the City of David. Instead, he took it aside to the house of Obed-Edom the Gittite. 14The ark of God remained with the family of Obed-Edom in his house for three months, and the LORD blessed his household and everything he had.

14:1Now Hiram king of Tyre sent messengers to David, along with cedar logs, stonemasons and carpenters to build a palace for him. 2And David knew that the LORD had established him as king over Israel and that his kingdom had been highly exalted for the sake of his people Israel.

3In Jerusalem David took more wives and became the father of more sons and daughters. 4These are the names of the children born to him there: Shammua, Shobab, Nathan, Solomon, 5Ibhar, Elishua, Elpelet, 6Nogah, Nepheg, Japhia, 7Elishama, Beeliada and Eliphelet.

8When the Philistines heard that David had been anointed king over all Israel, they went up in full force to search for him, but David heard about it and went out to meet them. 9Now the Philistines had come and raided the Valley of Rephaim; 10so David inquired of God: “Shall I go and attack the Philistines? Will you hand them over to me?”

The LORD answered him, “Go, I will hand them over to you.”

11So David and his men went up to Baal Perazim, and there he defeated them. He said, “As waters break out, God has broken out against my enemies by my hand.” So that place was called Baal Perazim. 12The Philistines had abandoned their gods there, and David gave orders to burn them in the fire.

13Once more the Philistines raided the valley; 14so David inquired of God again, and God answered him, “Do not go straight up, but circle around them and attack them in front of the balsam trees. 15As soon as you hear the sound of marching in the tops of the balsam trees, move out to battle, because that will mean God has gone out in front of you to strike the Philistine army.” 16So David did as God commanded him, and they struck down the Philistine army, all the way from Gibeon to Gezer.

17So David’s fame spread throughout every land, and the LORD made all the nations fear him.

15:1After David had constructed buildings for himself in the City of David, he prepared a place for the ark of God and pitched a tent for it. 2Then David said, “No one but the Levites may carry the ark of God, because the LORD chose them to carry the ark of the LORD and to minister before him forever.”

3David assembled all Israel in Jerusalem to bring up the ark of the LORD to the place he had prepared for it. 4He called together the descendants of Aaron and the Levites:

5From the descendants of Kohath,

Uriel the leader and 120 relatives;

6from the descendants of Merari,

Asaiah the leader and 220 relatives;

7from the descendants of Gershon,

Joel the leader and 130 relatives;

8from the descendants of Elizaphan,

Shemaiah the leader and 200 relatives;

9from the descendants of Hebron,

Eliel the leader and 80 relatives;

10from the descendants of Uzziel,

Amminadab the leader and 112 relatives.

11Then David summoned Zadok and Abiathar the priests, and Uriel, Asaiah, Joel, Shemaiah, Eliel and Amminadab the Levites. 12He said to them, “You are the heads of the Levitical families; you and your fellow Levites are to consecrate yourselves and bring up the ark of the LORD, the God of Israel, to the place I have prepared for it. 13It was because you, the Levites, did not bring it up the first time that the LORD our God broke out in anger against us. We did not inquire of him about how to do it in the prescribed way.” 14So the priests and Levites consecrated themselves in order to bring up the ark of the LORD, the God of Israel. 15And the Levites carried the ark of God with the poles on their shoulders, as Moses had commanded in accordance with the word of the LORD.

16David told the leaders of the Levites to appoint their brothers as singers to sing joyful songs, accompanied by musical instruments: lyres, harps and cymbals.

17So the Levites appointed Heman son of Joel; from his brothers, Asaph son of Berekiah; and from their brothers the Merarites, Ethan son of Kushaiah; 18and with them their brothers next in rank: Zechariah, Jaaziel, Shemiramoth, Jehiel, Unni, Eliab, Benaiah, Maaseiah, Mattithiah, Eliphelehu, Mikneiah, Obed-Edom and Jeiel, the gatekeepers.

19The musicians Heman, Asaph and Ethan were to sound the bronze cymbals; 20Zechariah, Aziel, Shemiramoth, Jehiel, Unni, Eliab, Maaseiah and Benaiah were to play the lyres according to alamoth, 21and Mattithiah, Eliphelehu, Mikneiah, Obed-Edom, Jeiel and Azaziah were to play the harps, directing according to sheminith. 22Kenaniah the head Levite was in charge of the singing; that was his responsibility because he was skillful at it.

23Berekiah and Elkanah were to be doorkeepers for the ark. 24Shebaniah, Joshaphat, Nethanel, Amasai, Zechariah, Benaiah and Eliezer the priests were to blow trumpets before the ark of God. Obed-Edom and Jehiah were also to be doorkeepers for the ark.

25So David and the elders of Israel and the commanders of units of a thousand went to bring up the ark of the covenant of the LORD from the house of Obed-Edom, with rejoicing. 26Because God had helped the Levites who were carrying the ark of the covenant of the LORD, seven bulls and seven rams were sacrificed. 27Now David was clothed in a robe of fine linen, as were all the Levites who were carrying the ark, and as were the singers, and Kenaniah, who was in charge of the singing of the choirs. David also wore a linen ephod. 28So all Israel brought up the ark of the covenant of the LORD with shouts, with the sounding of rams’ horns and trumpets, and of cymbals, and the playing of lyres and harps.

29As the ark of the covenant of the LORD was entering the City of David, Michal daughter of Saul watched from a window. And when she saw King David dancing and celebrating, she despised him in her heart.

16:1They brought the ark of God and set it inside the tent that David had pitched for it, and they presented burnt offerings and fellowship offerings before God. 2After David had finished sacrificing the burnt offerings and fellowship offerings, he blessed the people in the name of the LORD. 3Then he gave a loaf of bread, a cake of dates and a cake of raisins to each Israelite man and woman.

4He appointed some of the Levites to minister before the ark of the LORD, to make petition, to give thanks, and to praise the LORD, the God of Israel: 5Asaph was the chief, Zechariah second, then Jeiel, Shemiramoth, Jehiel, Mattithiah, Eliab, Benaiah, Obed-Edom and Jeiel. They were to play the lyres and harps, Asaph was to sound the cymbals, 6and Benaiah and Jahaziel the priests were to blow the trumpets regularly before the ark of the covenant of God.

7That day David first committed to Asaph and his associates this psalm of thanks to the LORD:

8Give thanks to the LORD, call on his name;

make known among the nations what he has done.

9Sing to him, sing praise to him;

tell of all his wonderful acts.

10Glory in his holy name;

let the hearts of those who seek the LORD rejoice.

11Look to the LORD and his strength;

seek his face always.

12Remember the wonders he has done,

his miracles, and the judgments he pronounced,

13O descendants of Israel his servant,

O sons of Jacob, his chosen ones.

14He is the LORD our God;

his judgments are in all the earth.

15He remembers his covenant forever,

the word he commanded, for a thousand generations,

16the covenant he made with Abraham,

the oath he swore to Isaac.

17He confirmed it to Jacob as a decree,

to Israel as an everlasting covenant:

18“To you I will give the land of Canaan

as the portion you will inherit.”

19When they were but few in number,

few indeed, and strangers in it,

20they wandered from nation to nation,

from one kingdom to another.

21He allowed no man to oppress them;

for their sake he rebuked kings:

22“Do not touch my anointed ones;

do my prophets no harm.”

23Sing to the LORD, all the earth;

proclaim his salvation day after day.

24Declare his glory among the nations,

his marvelous deeds among all peoples.

25For great is the LORD and most worthy of praise;

he is to be feared above all gods.

26For all the gods of the nations are idols,

but the LORD made the heavens.

27Splendor and majesty are before him;

strength and joy in his dwelling place.

28Ascribe to the LORD, O families of nations,

ascribe to the LORD glory and strength,

29ascribe to the LORD the glory due his name.

Bring an offering and come before him;

worship the LORD in the splendor of his holiness.

30Tremble before him, all the earth!

The world is firmly established; it cannot be moved.

31Let the heavens rejoice, let the earth be glad;

let them say among the nations, “The LORD reigns!”

32Let the sea resound, and all that is in it;

let the fields be jubilant, and everything in them!

33Then the trees of the forest will sing,

they will sing for joy before the LORD,

for he comes to judge the earth.

34Give thanks to the LORD, for he is good;

his love endures forever.

35Cry out, “Save us, O God our Savior;

gather us and deliver us from the nations,

that we may give thanks to your holy name,

that we may glory in your praise.”

36Praise be to the LORD, the God of Israel,

from everlasting to everlasting.

Then all the people said “Amen” and “Praise the LORD.”

37David left Asaph and his associates before the ark of the covenant of the LORD to minister there regularly, according to each day’s requirements. 38He also left Obed-Edom and his sixty-eight associates to minister with them. Obed-Edom son of Jeduthun, and also Hosah, were gatekeepers.

39David left Zadok the priest and his fellow priests before the tabernacle of the LORD at the high place in Gibeon 40to present burnt offerings to the LORD on the altar of burnt offering regularly, morning and evening, in accordance with everything written in the Law of the LORD, which he had given Israel. 41With them were Heman and Jeduthun and the rest of those chosen and designated by name to give thanks to the LORD, “for his love endures forever.” 42Heman and Jeduthun were responsible for the sounding of the trumpets and cymbals and for the playing of the other instruments for sacred song. The sons of Jeduthun were stationed at the gate.

43Then all the people left, each for his own home, and David returned home to bless his family.

17:1After David was settled in his palace, he said to Nathan the prophet, “Here I am, living in a palace of cedar, while the ark of the covenant of the LORD is under a tent.”

2Nathan replied to David, “Whatever you have in mind, do it, for God is with you.”

3That night the word of God came to Nathan, saying:

4“Go and tell my servant David, ‘This is what the LORD says: You are not the one to build me a house to dwell in. 5I have not dwelt in a house from the day I brought Israel up out of Egypt to this day. I have moved from one tent site to another, from one dwelling place to another. 6Wherever I have moved with all the Israelites, did I ever say to any of their leaders whom I commanded to shepherd my people, “Why have you not built me a house of cedar?”’

7“Now then, tell my servant David, ‘This is what the LORD Almighty says: I took you from the pasture and from following the flock, to be ruler over my people Israel. 8I have been with you wherever you have gone, and I have cut off all your enemies from before you. Now I will make your name like the names of the greatest men of the earth. 9And I will provide a place for my people Israel and will plant them so that they can have a home of their own and no longer be disturbed. Wicked people will not oppress them anymore, as they did at the beginning 10and have done ever since the time I appointed leaders over my people Israel. I will also subdue all your enemies.

“‘I declare to you that the LORD will build a house for you: 11When your days are over and you go to be with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, one of your own sons, and I will establish his kingdom. 12He is the one who will build a house for me, and I will establish his throne forever. 13I will be his father, and he will be my son. I will never take my love away from him, as I took it away from your predecessor. 14I will set him over my house and my kingdom forever; his throne will be established forever.’”

15Nathan reported to David all the words of this entire revelation.

16Then King David went in and sat before the LORD, and he said:

“Who am I, O LORD God, and what is my family, that you have brought me this far? 17And as if this were not enough in your sight, O God, you have spoken about the future of the house of your servant. You have looked on me as though I were the most exalted of men, O LORD God.

18“What more can David say to you for honoring your servant? For you know your servant, 19O LORD. For the sake of your servant and according to your will, you have done this great thing and made known all these great promises.

20“There is no one like you, O LORD, and there is no God but you, as we have heard with our own ears. 21And who is like your people Israel—the one nation on earth whose God went out to redeem a people for himself, and to make a name for yourself, and to perform great and awesome wonders by driving out nations from before your people, whom you redeemed from Egypt? 22You made your people Israel your very own forever, and you, O LORD, have become their God.

23“And now, LORD, let the promise you have made concerning your servant and his house be established forever. Do as you promised, 24so that it will be established and that your name will be great forever. Then men will say, ‘The LORD Almighty, the God over Israel, is Israel’s God!’ And the house of your servant David will be established before you.

25“You, my God, have revealed to your servant that you will build a house for him. So your servant has found courage to pray to you. 26O LORD, you are God! You have promised these good things to your servant. 27Now you have been pleased to bless the house of your servant, that it may continue forever in your sight; for you, O LORD, have blessed it, and it will be blessed forever.”

THE ACCOUNT OF King David’s installation of the ark of the covenant in Jerusalem for the purpose of establishing a central religious shrine in Israel forms a single literary unit. Chapter 17 is often omitted in the discussion of the Chronicler’s ark narrative and is treated in isolation as a distinct section. Yet, God’s covenant with David stands appropriately as the conclusion to the ark narrative. In the first section (chs. 13–16), David aspires to build a suitable “house” for the ark of the covenant so that the name of Yahweh might be enthroned. Conversely, in the second section (ch. 17), God promises to build David’s “house” into a royal dynasty. In each case, the objective is the same—establishing the greatness of the name of Yahweh (17:24).

More than explaining how the ark of the covenant came to be established at a permanent site in Jerusalem, the ark narrative tells the story of the transformation of the former Jebusite stronghold into the political and religious center of the Israelite monarchy.1 The installation of the ark in a temporary shrine in Jerusalem was the second phase of this transformation. The first phase was the capture of the city itself by cunning and courage on the part of David’s army (cf. 11:4–9). These two phases, along with the earlier report of David’s being crowned as king by all Israel, are three essential elements to the preparations for the building of Yahweh’s temple—a focal point of the Chronicler’s interest in his retelling of Israel’s history.

Broadly speaking, the Chronicler relies on the earlier parallel account of David’s transfer of the ark of the covenant to center stage in the religious life of Israel found in 2 Samuel 5–6. His reordering and selective highlighting of those materials, however, once again demonstrate the Chronicler’s literary purposes are primarily thematic and theological—not chronological.2

By way of genre identification, chapters 13–17 form a “report” or narrative consisting of a complex series of “reports” (with the exception of the composite psalm in ch. 16). The “report” is a brief, self-contained narrative subgenre describing a single event or situation.3 Chapters 13–16 largely avoid dialogue, while the dialogue characterizing the report of chapter 17 features prophetic oracle and prayer. The story line hinges on the dramatic twist of David’s failure in his first attempt to transfer the ark of Yahweh into Jerusalem and the irony of God’s promising to build David’s “house” before David has the opportunity to fulfill his desire to build God’s “house.” The passage may be divided into six smaller units:

1. First stage of the ark’s transfer: from Kiriath Jearim to Kidon (13:1–14)

2. King David’s fame spreads (14:1–17)

3. Jerusalem made ready for the entrance of the ark (15:1–24)

4. Second stage of the ark’s transfer: the processional into Jerusalem (15:25–16:3)

5. Yahweh enthroned on Israel’s praise (16:4–43)

6. Yahweh’s covenant with David (17:1–27)

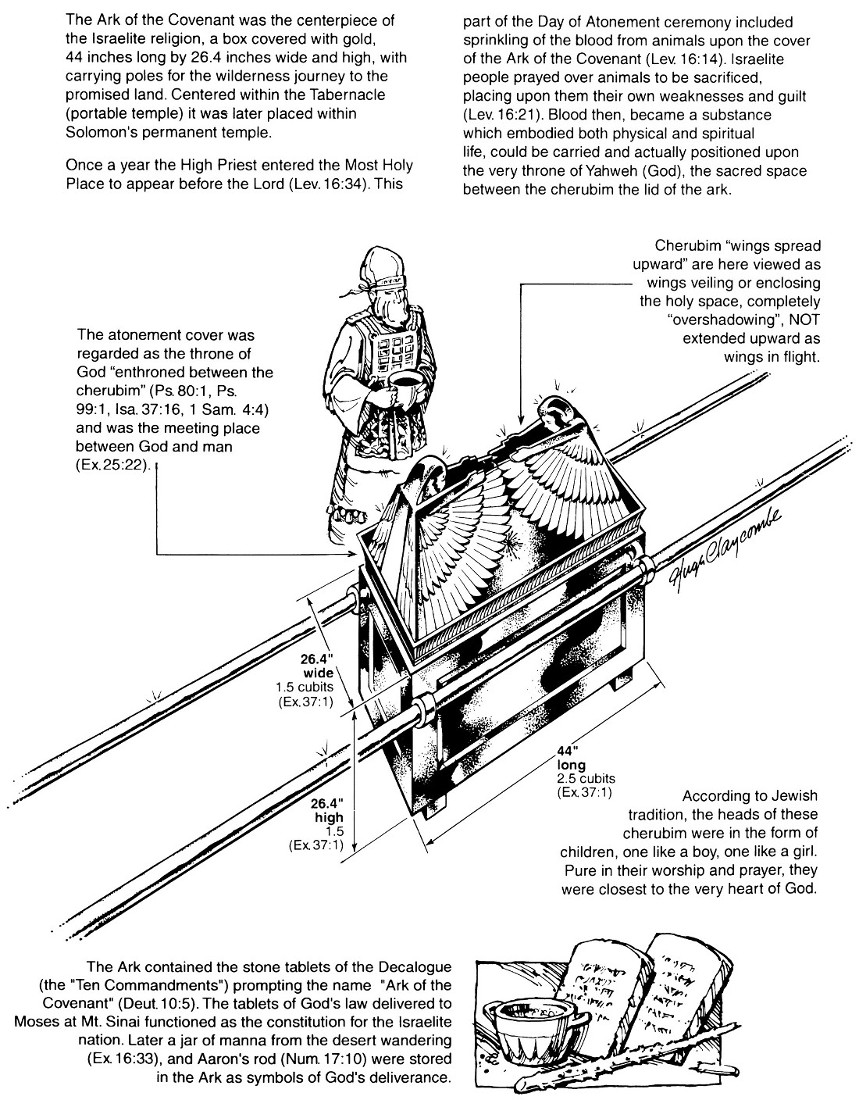

The centerpiece of this portion of the Chronicler’s history is a piece of tabernacle furniture, the ark of the covenant. The ark was a rectangular chest made of acacia wood and overlaid with gold (cf. Ex. 25:10–22). The box measured 2.5 cubits long by 1.5 cubits high and 1.5 cubits wide (roughly 3.75 ft. × 2.5 ft. × 2.5 ft.; see fig. 7 [on the following page] for a drawing of the ark of the covenant). The ark rested on four short legs equipped with rings for transporting on a set of wooden poles, also overlaid with gold. The ark and its carrying poles were the only pieces of furniture in the Most Holy Place (26:31–35). The ark contained the stone tablets of the Decalogue, hence the name for this sacred chest—“the ark of the covenant” (Deut. 10:5). Also housed in the ark was a jar of manna from the desert wandering of the Israelites after the Exodus (Ex. 16:33), Aaron’s rod (Num. 17:10), and later a complete book of the Law was placed beside the ark (Deut. 31:26; cf. Heb. 9:4).

Atop the ark was a lid of pure gold called the “atonement cover” (NIV) or “mercy seat” (NRSV; Ex. 37:6–9). Fixed at the ends of this lid were two cherubim facing each other, with wings outstretched. Above the cover of the box and between the cherubim is where God met with Israel (25:22). Thus, the ark became the symbol of God’s presence in the midst of Israel. Since the ark also contained the law of Moses, it also symbolized the Mosaic covenant enacted at Sinai. David’s concern for properly housing and attending to the ark of God represented his obedience to the law of Moses. According to Selman, this provided a natural lead-in to the announcement of the Davidic covenant for the Chronicler (ch. 17).4 A third aspect of the ark’s symbolism—the rule of God over Israel and all creation—will be developed in more detail later in this chapter.

First Stage of the Ark’s Return (13:1–14)

THE OPENING SECTION of the Chronicler’s ark narrative records the decision to retrieve the ark of God from Kiriath Jearim (13:1–4). These verses introduce the story of the ark’s eventual entry into Jerusalem and have no parallel in the Samuel account. The latter portion of this literary unit describes the journey of the ark from the house of Abinadab of Kiriath Jearim (or Baalah) to the threshing floor of Kidon (13:5–14). This account of the transfer of the ark is taken from 2 Samuel 6:2–11 with some variation. Three smaller units may be observed in this section: the journey of all Israel to Kiriath Jearim (13:5–6), the transportation of the ark in a processional (13:7–11), and the temporary deposit of the ark at the house of Obed-Edom (13:12–14).

Fig. 7. The Ark of the Covenant

We must recall that the ark of the covenant had been captured in battle by the Philistines when the Israelites foolishly assumed the symbol of God’s presence at the vanguard of the army would guarantee a military victory (1 Sam. 4:11). Not long after their capture of the ark, the Philistines returned the sacred chest to the Israelites to stay the plagues the Lord inflicted on them (1 Sam. 5). The ark of God was returned to Beth Shemesh, but only briefly. God struck dead seventy of the villagers for their irreverence in peeking into the contents of the covenant box (6:19). Terrified, the leaders of Beth Shemesh sent the ark to Kiriath Jearim, where it was housed by Abinadab and guarded by his son Eleazar (7:1). It is at this point that the Chronicler picks up the story.

The book of 2 Samuel treats the transfer of the ark of God as a military event initially (2 Sam. 6:1). The Chronicler adds the details that David consults not only with his military leaders but also the religious leadership of Israel (priests and Levites) and the general populace (1 Chron. 13:2). The thirty thousand chosen to escort the ark (2 Sam. 6:1) are apparently representative of “all Israel” for the Chronicler (1 Chron. 13:5). The unity of “all Israel” under King David is a key theme in Chronicles; here it connects the preceding section (chs. 10–12) with the ark narrative (chs. 13–17).

David’s call to “bring the ark of our God back to us” connotes a spiritual journey as much as it denotes a geographical one (13:3a). The site of Kiriath Jearim was located in the tribe of Judah (13:6), so the issue is not the physical presence of the ark of God. Japhet correctly discerns that David in fact admonishes the people in a spiritual sense: “Let us make the ark ‘ours.’”5 She substantiates her interpretation by the appeal to once again “inquire” of the ark, as it was neglected during Saul’s reign (13:3b). The issue for Israel is the role of the ark “in God’s worship, as an object of ‘seeking.’”6 The word “inquire” (drš) displays a wide range of meaning, including “seeking” God in the sense of “worship” (e.g., 2 Chron. 17:3). The full conclusion of the installation of the ark, as Japhet reminds us, “is not seen in its placement ‘inside the tent’ (1 Chron. 16:1//2 Sam. 6:17), but in the establishment of a permanent liturgy of worship before it” (described in 1 Chron. 16).7

Implicit in David’s summons to restore the ark to its proper place in Israelite worship is the cause-and-effect link between Saul’s demise and Israel’s defeat by the Philistines and the neglect of the ark of God (13:3c). In fact, the writer probably intends his audience to recall the earlier theological assessment of King Saul as one who did not “inquire” (drš) of Yahweh (10:14). That sober reminder alone may have been enough to motivate the assembly of Israel to decide that “to return the ark” is the right thing to do (13:4).

Affirming the prominent theme of Israelite unity under King David, the Chronicler indicates in threefold repetition that “all the Israelites” participate with King David in the processional to return the ark of God (13:5, 6, 8). This phrase interprets the “thirty thousand men” chosen out of Israel to accompany the ark in the Samuel parallel as a throng representative of “all Israel” (cf. 2 Sam. 6:1).

The Chronicler’s elaboration on the extent to which this multitude represents the breadth of the territory of Israel is noteworthy (13:5). Typically, the Old Testament boundaries or geographical poles for the land of Israel are Dan in the north and Beersheba in the south (cf. 21:2). The Chronicler’s extreme definition of the borders of Israel extending from the Shihor River in Egypt (or the Nile) to Lebo Hamath (the city at the entrance to the territory of Hamath in Syria some forty-five miles north of Damascus) occurs elsewhere in the Old Testament only in Joshua 13:2–5. There the Shihor River and Lebo Hamath are the “bookends” for the territories still unconquered by the Hebrews prior to Joshua’s death. The Chronicler may be making two statements in his appeal to the precursor text in Joshua: (1) The rarely used geographical description maximizes the sweeping extent of David’s support; (2) it may offer commentary on Joshua 13:2–5 in the sense that under King David the conquest of Canaan is finally completed.

The point of departure for the processional transferring the ark of God to the central shrine in Jerusalem is Kiriath Jearim (1 Chron. 13:5). The city was a border town between Judah and Benjamin located approximately eight miles west of Jerusalem. The site was also known as Kiriath Baal and Baalah (Josh. 15:9; 18:14, 15; cf. 2 Sam. 6:2).

The portrayal of Yahweh as “the LORD, who is enthroned between the cherubim” (13:6) is an infrequent but powerful image of the God of the Hebrews (cf. 1 Sam. 4:4; 2 Kings 19:15). The idea of the mysterious and majestic presence of God enthroned between the cherubim of the ark of the covenant is based on the understanding that this is where God meets his people (Ex. 25:22). The idea behind God’s “meeting” with Israel is comparable to that of a king holding audience with subjects—hence, the ark represented the throne of God on earth. The psalmist associates the enthronement of God between the cherubim of the ark with his sovereign rule of the nations (Ps. 99:1). Clearly, he wants to impress on his audience the fact that Yahweh is not a local deity after the fashion of the gods and goddesses of the pantheons of Israel’s neighbors. Rather, the Lord Almighty is a universal deity, and his rule encompasses all of creation.

The NIV’s expression, “the ark that is called by the Name,” is interpretive (13:6d). The literal clause, “where [the] Name is called” is cryptic. Some commentators suggest the expression is a later addition to the text.8 If Chronicles preserves a better version of original Hebrew text than Samuel, then the expression should be retained as original and probably signifies that the ark and the shrine housing it are the “local” manifestations of the divine presence—the “house” or residence of God, so to speak (cf. Deut. 12:11; 1 Kings 8:29).

There are numerous divergences between 2 Samuel 6:2–11 and 1 Chronicles 13:6–14. For instance, the MT of 2 Samuel 6:5 reads “celebrating before the LORD with all kinds of instruments made of pine” (see NIV text note). As a second example, the site of Uzzah’s tragic death is the “threshing floor of Kidon” (1 Chron. 13:9), whereas the place name in Samuel is Nacon (2 Sam. 6:6); other witnesses identify the site as Nodan (4QSama) or Nodab (LXXb). Williamson has noted these variants are of textual interest in the reconstruction of the original MT, but that reading theological significance into them is unwarranted.9

The deadly mishap involving Uzzah (13:9) dramatically and immediately changes the mood surrounding the transfer of the ark of the covenant. The festive enthusiasm and joyous celebration of the procession suddenly turn into confusion, despair, and mourning. Interestingly, the Chronicler avoids all comment on the response of the Israelites participating in the event. What is clear is that Uzzah is struck down and killed by the Lord (13:10). King David’s response of both anger and fear to the tragedy is also readily reported (13:11–12). David’s visceral reaction seems to be based on the assumption that Uzzah is an innocent victim and that God has capriciously shown his disapproval for the enterprise of transferring the ark.

The death of Uzzah resulting in the bungled transfer of the ark of the covenant is one of two failures of King David reported by the Chronicler (the other is the census-taking, 1 Chron. 21). In part, the explanation for David’s failure is found in the repeated phrase “before God” (13:8, 10). David and Israel overlook the role of the ark as the “vehicle of God’s presence in the midst of his people.”10 The awesome power and dreadful holiness of God have somehow been forgotten. Perhaps the euphoria of the celebration has dulled the “theological senses” of both king and people. The physical separation of the ark from the sacred shrine still located in Gibeon (cf. 1 Chron. 16:39; 21:29–30) may have contributed to an unhealthy familiarity with this piece of sacred furniture normally viewed but once a year by the high priest.

Whatever the reason, the fatal experience of Nadab and Abihu’s profane behavior “before the LORD” has faded from memory (cf. Lev. 10:1–3). God is a consuming fire, and he will show himself holy before all people, even in the stumbling of oxen pulling a cart at the threshing floor of Kidon (cf. Ex. 24:17; Deut. 4:24; Heb. 12:29). The Chronicler’s repetition of the word “break out” (prṣ) in this section of the narrative seems to draw attention to this terrifying dimension of God’s character—perhaps as a necessary reminder to his audience (cf. 13:11; 14:11; 15:13).

A more complete explanation of David’s failure ensues in the subsequent narrative, phase two of the transfer of the ark to Jerusalem. Here we learn that King David fails to “inquire” of the Lord as to the proper procedure for transporting the ark (15:13). According to Mosaic law, only the Levites were to carry the holy things of the tabernacle, and even they were not to touch the holy vessels against the threat of death (Num. 4:15). Accordingly, David orders the consecration of the priests to transport the ark by means of the carrying poles prescribed by pentateuchal law (1 Chron. 15:2–24; cf. Ex. 25:14). Ironically, David’s neglect to inquire of the Lord mimics that of King Saul’s (1 Chron. 10:14). Unlike Saul’s habitual neglect of God, however, David’s lapse is temporary and is remedied by his later entreaty for divine instruction in the transfer of the ark.

Selman has suggested King David and the other leaders are influenced by the Philistines and their use of a “new cart” to restore the ark to the Israelites, thus unwittingly perpetuating a pagan superstition (13:7; cf. 1 Sam. 6:7).11 This may have indeed been the case. But it is not the central issue in understanding the outbreak of God’s wrath and the slaying of Uzzah. According to Japhet, the touching of sacred objects was a sacrilege (see Num. 4:15). Consequently, “a sin of this kind is objective and absolute, the aspects of volition, intent, and moral consideration playing no role.”12 God’s response to such desecration of the holy is consistent with the Chronicler’s report (e.g., Num. 15:35; Josh. 7:25; 1 Sam. 6:19). Japhet further characterizes Uzzah’s sin as one of disbelief and mistrust in the power of God, since it is for God and not human beings to protect the ark (the essential lesson of Shiloh, 1 Sam. 4–6).13

David’s refusal to press on with his quest to transfer the ark to Jerusalem marks two important character traits of this beloved shepherd-king (13:13–14). (1) His disposition to deposit the ark at the nearest convenient location indicates his submission to God’s will (cf. Ps. 40:8). (2) Whether out of abject fear or outright reverence, David refuses to manipulate God for personal advantage through control of the sacred symbol of divine presence (cf. Ps. 40:6; 51:6).

There is some question as to the identity of Obed-Edom. Some commentators have suggested he is a Philistine since he is associated with Gath (13:13; “Gittite” is related to Gath) and that David deliberately warehouses the ark with a “foreigner” as a sort of “guinea pig” to ensure that God’s wrath has indeed subsided.14 Others equate him with the Obed-Edom named by the Chronicler among the Levitical gatekeepers (15:18, 21).15 There is no doubt, however, about the purpose of the Chronicler’s report of God’s blessing on the house of Obed-Edom for those three months the ark resides in his keeping. David and all Israel (as well as the Chronicler’s audience) need to know that the transgression against God was not the transfer of the ark itself but the faulty way in which it was carried out. God demands proper “means” to achieve good and right “ends.”

King David’s Fame Spreads (14:1–17)

THE THREE REPORTS comprising chapter 14 are taken from 2 Samuel 5:11–25: (1) the assistance provided by King Hiram of Tyre for the building of David’s palace (1 Chron. 14:1–2), (2) the children born to King David during the Jerusalem era of his reign (14:3–7), and (3) two successful military campaigns waged by King David against the Philistines (14:8–17).

The Chronicler’s rearrangement of the Samuel narrative shifts these events of David’s kingship out of strict chronological order. His editing of the Samuel parallel may have been motivated by theological reasons; that is, in contrast to King Saul’s unfaithfulness, David’s faithfulness, demonstrated in his seeking of the ark of God, is blessed by God (cf. 10:13). It is also possible that the “cutting and pasting” in Chronicles is a literary device the writer uses to account for the three-month time lapse between the first and second phases of the installation of the ark of the covenant in Jerusalem (cf. 13:14).16

King Hiram (Heb. Huram, most often in Chronicles) of Tyre was an ally of both David and Solomon (14:1–2). His name may be a shortened form of Ahiram. The dates for his rule of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre are uncertain, although it is clear his reign overlaps that of David and Solomon since he was the “contractor” for the Jerusalem temple (2 Chron. 2:12–14). Most likely Hiram ruled from about 980–950 B.C., but scholarly estimates vary widely.17 Hiram’s gift of construction materials and craftsmen for the building of David’s palace may have been part of a trade agreement, much like that arranged later with Solomon (building supplies in exchange for food staples, 2 Chron. 2:15–16). Hiram’s desire to “build a house” for David foreshadows the same motif in chapter 17, where David seeks to build a house for Yahweh but instead learns of Yahweh’s desire to “build a house” for him.

The Jerusalem birth report and name list assume the audience’s knowledge of the Hebron birth report and name list (2 Sam. 3:2–5). The list of David’s children born in Jerusalem essentially repeats 2 Samuel 5:13–16, with the exception of two additional names: Elpelet and Nogah.18 The omission of these names in Samuel may have been due to the untimely deaths of the children.19 The genealogy in Chronicles also includes the names of the mothers of David’s children as well as those of his daughters (1 Chron. 3:4b–9). Unlike King Saul’s dynasty, which died out (10:6), David’s house is a “fruitful vine” (cf. Ps. 128:3).

The news of David’s being anointed as king of Israel prompts a Philistine invasion of Judah, presumably an attempt to dethrone him before their former vassal has sufficient time to solidify his power among God’s people (14:8–12). The attack takes place at the Valley of Rephaim, a border region between the tribes of Benjamin and Judah, immediately southwest of Jerusalem (Josh. 15:8). Unlike King Saul, who “inquired” (drš) of the medium of Endor (1 Sam. 28:7), David “inquired” (šʾl) of the Lord and was assured victory over the Philistines (1 Chron. 14:10). Previously God had “broken out” (prṣ) in anger against Uzzah (and Israel) for failing to respect his holiness (13:11); now God “breaks out” (prṣ) against the Philistines (14:11).

Earlier, the Israelites lost the ark of the covenant to the Philistines in the battle of Shiloh (1 Sam. 4:11). Here at Rephaim the Philistines abandon their gods on the battlefield, symbolic of their impotence before Yahweh, the true God (14:12). Rather than plunder the idols and parade them as trophies of war, David burns the relics of false worship in accordance with the law of Moses (Deut. 7:5; 12:3).

The Philistines launch a second offensive at the same location, although the interval of time between the two attacks is unspecified (14:13–16). As before, the narrative reports that David appropriately “inquires” of God as to his response to the Philistine aggression (14:14). Once again, David is assured of God’s help in battle, but this time the tactics are changed. Instead of meeting the enemy in a head-on clash, David is instructed to entrap the enemy by circling around the Philistine army. The divine signal for engaging the enemy is most unusual, as David and his army are cautioned to wait for the “sound of marching” in the treetops before attacking (14:15). The rustling of the leaves in the trees is most likely the Spirit of God, since David is told God will go before him in battle. The noise, perhaps akin to soldiers’ feet rushing into battle, is designed to confuse the Philistine army (cf. 2 Kings 7:6). David and the Israelites rout the Philistines and drive them in a northwesterly direction away from Jerusalem through Gibeon (or Gibeah?; cf. “Geba” in 2 Sam. 5:25) to Gezer (1 Chron. 14:16).

The spread of David’s fame and the fear of Yahweh among the nations are interrelated (14:17). As God blesses David’s faithfulness, so David’s success brings glory and honor to God. The Chronicler’s report of David’s growing reputation foreshadows the covenant blessing of God’s promise to make David’s name among the greatest of the world (17:8). Fittingly, the defeat of the Philistines at Rephaim reverses the outcome at Mount Gilboa and avenges the deaths of Saul and Jonathan, closing the story on that tragic first chapter in the history of Israelite kingship. Presumably the Chronicler intends this account of the reversal of fortune for Israel under King David as a message of hope and encouragement for his audience—“fodder” for possibility thinking on the part of his generation.

Jerusalem Made Ready for the Entrance of the Ark (15:1–24)

THIS SECTION FURTHERS the account of the transfer of the ark of the covenant by detailing the preparations made by David in response to the failure of his first initiative. The passage may be divided into three smaller units: the provisional preparations for transferring the ark (15:1–3), the summons and purification of the Levites (15:4–15), and the duty roster of the Levitical musicians (15:16–24). By way of literary genre the material is essentially considered report, with interesting subfeatures like the edict (i.e., a proclamation carrying the force of law, 15:2), the name list with tallies (15:5–10), and the duty roster (15:16–24). The material has no parallel in 1–2 Samuel. Yet, there is no need to assume the account is the Chronicler’s invention. We have already seen that he has access to several sources not included in the books of Samuel and Kings.

Before we comment on this passage, J. A. Thompson makes an interesting observation. He has noted that the Chronicler’s narrative devoted to the transfer of the ark of God gives careful attention to an object that “had already ceased to exist [italics his]” by the writer’s own time.20 That is, the Chronicler’s audience has no opportunity to worship before the ark as did David because the sacred chest was lost or destroyed during the Exile. At least there is no record that this piece of furniture was part of the inventory of temple vessels and articles returned to Jerusalem under Persian auspices (cf. Ezra 1:7–11). Nor is there any evidence that a replica of the ark was constructed for use in Zerubbabel’s temple by the postexilic community. Thompson correctly deduces that the issue is not the ark as a sacred object, but what that piece of furniture represents: the mobile presence of God among his people and his uncompromising holiness.21

The report of the “tent” David pitches for temporarily housing the ark (15:1) emphasizes the thoroughness of his preparations for transferring the ark (cf. 15:12). More important to the venture of relocating the ark of God in Jerusalem is the role of the Levites as porters (15:2). This time the ark is to be carried by the Levites, not driven on a cart (also noted in the Samuel parallel by “those … carrying the ark”; 2 Sam. 6:13). David has learned from his earlier mistake in transporting the ark, although the text is silent as to the source of the instruction. The tone and circumstance of David’s lecture to the priests concerning their role in the transfer of the ark suggests God himself may have revealed this to David through the king’s study of the Mosaic law (Deut. 10:8: 18:5; cf. 1 Chron. 15:13).

The Chronicler is careful to include the priests (“descendants of Aaron”) and the “Levites” (15:4) in the assembly of “all Israel” (15:3). As noted previously, the military, religious, and civilian sectors of the population are consulted and incorporated into the processional for the transfer of the ark of God. The sons of Levi (Kohath, Merari, and Gershon) give their names to the three primary clans of the Levitical corps (Num. 3:17–20).

The Chronicler also lists three additional families in 15:8–10 (Elizaphan, Hebron, and Uzziel), all descendants of Kohath (cf. 6:18; 2 Chron. 29:13). Thompson has suggested these families have risen to a place of prominence either because of size or prestige.22 Some commentators contend this section of the name list simply reflects those clans of the Levites who have assumed leadership roles during the Chronicler’s own day. More clear is the role of the Kohathites in relationship to the ark of the covenant, since they were the clan charged by Moses to attend and transport the ark (Num. 3:31; 4:4–6, 15). In his appointment of the proper Levitical clan to transport the ark, King David again demonstrates his faithfulness to God’s commands.

David’s preparations for the transfer of the ark extend beyond the readying of a site for housing it to the personnel responsible for transporting and attending the sacred chest (15:11–15). David assigns the task of “consecrating” the priesthood to eight Levitical clan leaders (15:11), six of whom are included in the previous name list (Uriel, Asaiah, Joel, Shemaiah, Eliel, and Amminadab). The names of the two priests, Zadok and Abiathar, need not be considered secondary additions to the text (based on the influence of 2 Sam. 15:24–29).23 Following the original pattern of priestly ordination, the priests would first purify themselves. In turn, they would then be fit to purify the rest of the Levitical priesthood (cf. Ex. 29; Lev. 8).

The word “consecrate” (15:12, 14) means to set things or persons apart from impurity and profane use and dedicate them to the service of God in holiness. Chronicles records the similar consecration of the Levitical priesthood during the reigns of Solomon (2 Chron. 5:11), Hezekiah (29:5), and Josiah (35:6). In each case, Selman has noted, God subsequently blesses the nation.24 The act of consecration included ritual washing and abstinence from sexual relations (Ex. 19:14–15). Elsewhere we learn that priests and Levites are to avoid contact with corpses (Lev. 21:1–4) and are subject to more stringent requirements concerning marriage (21:13–15).

Interestingly, the Mosaic legislation threatens that God will “break out” (paraṣ) against the Israelites if the ritual purity of the Mount Sinai precinct is violated (Ex. 19:24). This is the same term used in Chronicles to describe the Lord’s anger against Uzzah (1 Chron. 13:11). The Chronicler makes it clear that faulty procedure that fails to recognize the holiness of God is responsible for the aborted attempt to transfer the ark (15:13). This time David and the religious leaders of Israel follow the prescriptions of the Mosaic code, calling for the priests to shoulder the ark on poles when transporting it (15:15; cf. Ex. 25:12–15; Num. 7:9). The necessity to obey the word of the Lord is a recurrent theme in Chronicles, since God’s blessing is directly tied to Israel’s observance of Mosaic law (cf. Deut. 28).

The concluding section of the report summarizing David’s extensive preparations for the transfer of the ark to Jerusalem (15:16–24) showcases the priests and Levites as musicians, another theme in Chronicles. The purpose in David’s appointments is simple: The Levitical corps is to provide appropriate music for the processional (15:16). The occasion of installing the ark in Jerusalem is to be celebratory and festive—the ark and God are to be “serenaded” into the city with joyous music. The king instructs the leaders of the Levites to divide their group into singers and musicians (15:16). The musicians are sorted into divisions on the basis of the instrument played (lyre, harp, or cymbal). The citation of Kenaniah as a musical director of sorts references his “skill” (or perhaps “musical knowledge”), suggesting the appointments of the Levites as singers and musicians may have been based on some type of audition (15:22).

Braun’s chart comparing the two different but related lists of Levitical singers and musicians is most helpful.25 List “A” (15:17–18) includes three leaders, eleven assistants, and two gatekeepers (reading 15:18 on the information supplied in 15:24 about Obed-Edom and Jehiah as gatekeepers, cf. 26:4). List “B” (15:19–24) records the same personnel with the addition of two more leaders (Azaziah and Kenaniah), two more gatekeepers (Berekiah and Elkanah), and seven priests assigned to blow trumpets (15:24). List “B” also rosters the Levites according to their musical instrument and perhaps the tunes to which the music was played (although the exact meaning of the words “alamoth” [15:20] and “sheminith” [15:21] is unclear; cf. the use of the terms in the headings of Ps. 6; 12; and 46).

The number and role of the gatekeepers is somewhat ambiguous (15:18, 23, 24). It was customary in the ancient world for doorkeepers to attend the various entrances of the palace complex, both to serve as guards and to welcome and announce those passing through the doors as part of the royal protocol. This may have been another way for David to show proper reverence to God as king as the ark enters the city of Jerusalem and is installed in the tent-sanctuary. On a more practical note, since the Levitical porters are carrying the ark on poles hoisted on their shoulders, the gatekeepers can see to it that another tragedy was averted by carefully directing the Levites as they crossed the thresholds of gates and doorways. The sacrifices offered along the way of the processional account for the inclusion of the priests in the Chronicler’s Levitical duty roster (15:26; 16:1–2).

Second Stage of the Ark’s Transfer: The Processional into Jerusalem (15:25–16:3)

THE CHRONICLER’S NARRATIVE now returns to the Samuel parallel (2 Sam. 6:12–16), with some variation. Notable in Chronicles is the emphasis on the priests and Levites in the logistics of the transfer of the ark. Chronicles also underscores the corporate effort of “all Israel” in the processional (1 Chron. 15:28; 16:3), whereas the perspective in Samuel is that of a heroic act on the part of King David (2 Sam. 6:12). The divine “help” afforded David (1 Chron. 15:26; cf. 12:18) is now extended to the Levitical corps as confirmation that this time the plans for the transfer of the ark are truly sanctioned by God.

David’s priestly role in the processional is tacitly approved by the detailed reference to the king’s garb: a linen robe and linen ephod (15:27; a vest or apron-like over-garment, like that of the Levites, cf. Ex. 39:27–29). Reflection on the event may have provided the impetus for David’s psalm referencing the priesthood of Melchizedek (Ps. 110:4). Perhaps it is this experience that prompts the appointment of his sons as “priests” of some sort (cf. 2 Sam. 8:18).

By contrast, David earns the disapproval of his wife Michal (15:29), Saul’s daughter. She “despises” (bzh) him for his joyous abandon in celebrating the transfer of the ark of God—to her own detriment, for as a result of rebuking the king, she is barren (2 Sam. 6:23). According to Selman, Michal is out of sympathy with David’s and all Israel’s concern for the ark.26 In one sense she represents the last vestige of King Saul’s “unfaithfulness,” and her story provides yet further justification for God’s rejection of Saul’s dynasty.

This portion of the account concludes with the successful installation of the ark of God in a tent, a temporary structure erected by David for housing the ark until a permanent shrine can be built. The Jerusalem tent is not to be confused with the Mosaic tabernacle, apparently located at Gibeon during David’s reign (cf. 16:39; 21:29).27

The “burnt offerings” (16:2) are sacrifices for sin and demonstrate dedication to God (cf. Lev. 1). The “fellowship offerings” signify the completion of a vow (David’s vow to honor the Lord by attending to the ark, 1 Chron. 13:3; cf. Ps. 132) and thankfulness on the part of all Israel for the blessings of God in sustaining the nation and establishing David as king (cf. Lev. 3). The communal blessing and ritual meal are part of a covenant-renewal ceremony in the biblical world (cf. Ex. 24:11). By installing the ark in Jerusalem, David is reestablishing God’s rule over Israel and Israel’s loyalty to Yahweh’s covenant with his chosen people. The relationship between God and Israel, the relationship of Israelite to Israelite, and the relationship of Israel to the nations are once again restored under the umbrella of the Mosaic covenant.

Yahweh Enthroned on Israel’s Praise (16:4–43)

THE PSALM OF THANKSGIVING commemorating the installation of the ark in Jerusalem, in one sense, is the theological center of the Chronicler’s retelling of Israel’s history. The installation of the ark marks Israel’s return to God under David’s leadership and a renewal of the nation’s covenant loyalty to the God of their ancestors. The ark itself symbolizes the covenant agreement established by Yahweh with Israel at Mount Sinai. The Sinai treaty was mediated by the prophet Moses, and the written record of that binding pact was archived for Hebrew posterity in the sacred ark. The Chronicler’s song of praise celebrates God as both covenant maker and covenant keeper, the lynchpin in his theology of hope for postexilic Judah.

King David’s appointment of certain members of the Levites to attend the ark indicates a division of labor among the Levitical corps. One group of Levites and the priests are stationed at the shrine in Gibeon housing the Mosaic tabernacle (16:39; 21:29). The other group of Levites are stationed in Jerusalem to minister before the ark of the Lord (16:4). The word “minister” (šrt) means “devout service” or “faithful attendance to ritual.” The duty rosters of 16:4–7 and 16:37–43 describe the postinstallation worship arrangements established for appropriately reverencing the presence of the ark in Jerusalem. The list of names in 16:5–6 is taken from the ledger of names found in 15:17–21. Presumably, those individuals omitted from that earlier catalog are assigned to duties in Gibeon.

The priestly and Levitical ministry centered in Gibeon remains one of maintaining the sacrificial worship of Israel. The Levitical ministry before the ark in Jerusalem is primarily musical in nature. Williamson has suggested the terms in 16:4 describing this ministry of music are related to the three types of songs in the anthology of the Psalms: “to make petition” (i.e., to invoke the Lord through psalms of lament), “to give thanks” (i.e., to sing the psalms of thanksgiving), and “to praise the LORD” (i.e., to laud God with the psalmic hymns).28 The NIV obscures the introduction to the composite psalm (16:7) by implying that David writes this psalm of thanksgiving and gives it to Asaph and the Levites for performance. The Hebrew more precisely states that David first assigns the activity of “giving thanks” to the Lord to Asaph and his relatives (cf. NASB, NRSV).29

The psalm of thanksgiving (16:8–36) is a composite of selections from three psalms:

1 Chronicles 16:8–22 = Psalm 105:1–15

1 Chronicles 16:23–33 = Psalm 96:1–13

1 Chronicles 16:34–37 = Psalm 106:1, 47–48

The psalmic composition, however, is not a random rearrangement of earlier poetic materials. The Chronicler has been influenced in his selection of poems from the Psalter by the vocabulary found in the immediate context of the narrative. Specifically, the account mentions several activities in connection with the installation of the ark, namely: “to make petition” (zkr), “to give thanks” (ydh), and “to praise” (hll). These three words are distributed throughout the composite psalm. Even more striking is the inverted parallelism or chiastic structure of the imperative forms of ydh and šir at the seams of the composite psalm:

“Give thanks to the LORD” |

[Heb. ydh] |

(1 Chron. 16:8 = Ps. 105:1) |

“Sing to him” |

[Heb. šir] |

(1 Chron. 16:9 = Ps. 105:2 |

“Sing to the LORD” |

[Heb. šir] |

(1 Chron. 16:23 = 96:1b + 2b) |

“Give thanks to the LORD” |

[Heb. ydh] |

(1 Chron. 16:34 = Ps. 106:1) |

This broad connective structure that mirrors the activities of “giving thanks” and “singing” to the Lord testify to the deliberate and skillful poetic arrangement on the part of the compiler.30

The theological themes of the three divisions of the composite psalm rehearse the key emphases of 1–2 Chronicles as a “biography” of God (see the introduction). (1) The first unit (16:7–22) highlights God as a covenant maker and keeper and Israel’s unique place among the nations as his elect (16:15–17). Without question, the emphasis in this extract from Psalm 105 on the “land of Canaan” as the inheritance of Israel is important to the Chronicler and his audience in the light of the recent Babylonian exile (1 Chron. 16:18). (2) The second unit (16:23–33) from Psalm 96 extols God as Creator and Sovereign over all the nations and over all their gods (1 Chron. 16:26, 30). (3) The third unit (16:34–36) from Psalm 106 praises the goodness and mercy of the God of salvation. Last, and not to be overlooked, the entire composite psalm repeats the covenant name Yahweh (NIV “LORD”) some sixteen times.

The members of the division of the Levitical corps assigned to Jerusalem reflect the name-lists of previous material (15:17–21; 16:4–6). Like the priestly ministry performed in the tabernacle of Moses, the ministry of worship before the ark is also a daily activity for the Jerusalem priests and Levites (16:37). Obed-Edom and his sixty-eight associates probably minister at the newly established sanctuary in some sort of rotation for a set number of days, although this is unspecified in the Chronicler’s account.

Obed-Edom apparently serves in the dual role of musician and gatekeeper (16:38; cf. 15:18, 21, 24). The relationship of this Obed-Edom to the Obed-Edom who housed the ark for three months after David’s first attempt to transfer the ark failed is unclear (cf. 13:13).

Critical scholarship tends to dismiss the tradition of a tabernacle at Gibeon as an invention of the Chronicler designed to justify King Solomon’s worship at Gibeon (16:39–42; 1 Kings 3:4; 2 Chron. 1:3). Such an argument is unnecessary, however, since we have already seen that the Chronicler has made use of other reliable historical sources in his retelling of Israelite history. The reference to the Gibeon sanctuary is important to the purpose of Chronicles because it demonstrates that King David has not neglected the Mosaic tabernacle. Likewise, the perpetuation of the morning and evening sacrifices commanded by the Torah is a further witness to David’s adherence to the law of Moses (cf. Ex. 29:39). Perhaps more crucial from the Chronicler’s perspective is establishing the historical and theological continuity between David’s tent-shrine in Jerusalem and the Mosaic tent-shrine in Gibeon. It seems likely that implicit in Zadok’s assignment to Gibeon as chief priest (1 Chron. 16:39) is the appointment of Abiathar as chief priest in Jerusalem (cf. 15:11).

Clearly the ministry of music on the part of the Levites is central to worship at both tent-sanctuaries. Both Heman and Jeduthun are known elsewhere as directors of Levitical musical guilds (cf. 25:1, 6; see also the headings of Ps. 39; 62; 77; 88). The musical refrain describing the thanksgiving of the Levites (“his love endures forever,” 1 Chron. 16:41) emphasizes the covenant loyalty, faithfulness, and steadfast love of God for Israel. Selman has aptly commented that this refrain celebrating the enduring love of God (16:34, 41) lies at the heart of Old Testament praise and worship.31

The report of King David’s departure to go home and bless his family (16:43) marks the Chronicler’s return to the Samuel parallel (2 Sam. 6:19b–20a). The verse serves as a conclusion to the narrative preserving the story of the transfer of the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem. It also introduces the following chapter, since David’s action foreshadows the covenant blessing God pronounces on the royal family.

The Davidic Covenant (17:1–27)

THE PROPHETIC ORACLE recounting God’s promise to build David’s royal dynasty has its precursor in 2 Samuel 7. The Chronicler’s version, though directly dependent on the earlier account, contains numerous divergences that may be attributed to an alternative manuscript tradition or the tendency for Chronicles to contemporize.32 Significant is the omission of the threat of punishment against the royal line for wrongdoing (cf. 2 Sam. 7:14). It is unclear whether the Chronicler has assumed the fulfillment of the divine warning in the Babylonian exile or considered the menace moot since the monarchy is only a memory at the time of his writing.

This narrative genre is classified broadly as “report,” specifically a prophetic commission report (17:3–15) and a prayer (17:16–27). The report contains a number of specialized formulas often found in prophetic literature, including the messenger formula (“this is what the LORD says,” 17:4, 7), the word formula (“the word of God came,” 17:3), the adoption formula (“I will be his father, and he will be my son,” 17:13), the self-abasement formula (“who am I?” 17:16), and the covenant formula (“you made your people Israel your very own,” 17:22).33

Chronicles is the story of two “houses”: the house or dynasty of King David and the house or temple of God. According to Selman, the building blocks for the Chronicler’s narrative are the two words from God—one blessing David’s house (17:3–15) and the other blessing the house King Solomon built for Yahweh in Jerusalem (2 Chron. 7:11–22).34 The passage may be divided into three logical units: David’s plan (1 Chron 17:1–2), Nathan’s oracle (17:3–15), and David’s prayer (17:16–27).

The contextual relationship to the preceding and following materials is ideological rather than literary or chronological. (1) The formal installment of the ark of God in Jerusalem is preliminary to David’s plan and all his preparations for building a permanent sanctuary for Yahweh (chs. 13–16). On this point, Williamson has noted that the remainder of 1 Chronicles is devoted to the single theme of the Jerusalem temple by noting the builder (ch. 17), setting the political conditions (chs. 18–20), drafting the plans and securing the materials (chs. 22; 28–29), and appointing the personnel (chs. 23–27).35 (2) God’s covenant with the house of David is understood as the natural outcome of Israel’s covenant renewal with God as a part of the ark installment ceremony. (3) The divine promise to build a Davidic dynasty in Israel is played out in the Chronicler’s subsequent record of the rise and fall of kingship in Israel (2 Chron. 1–36).

The Chronicler condenses the Samuel parallel (17:1–2 = 2 Sam. 7:1–3), omitting the reference to the “rest” enjoyed by King David (2 Sam. 7:1). That “rest” is only partial at best in terms of Israelite foreign policy. The Chronicler’s emphasis on David’s disqualification as builder of the temple because he is as a warrior (1 Chron. 22:8; 28:3) makes retention of the rest motif awkward contextually as well (cf. David’s wars in chs. 18–20).

David’s desire to build a temple for Yahweh is typical of royal behavior in the biblical world (17:1). In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia kings erected monuments and built great temples as an act of homage to the deity responsible for establishing them on the throne.36 It is only natural that David seeks to honor his God in like manner. Beyond this, David is shamed that Yahweh as the true king of Israel is confined to a tent-sanctuary while he himself enjoys the luxury of a palace of cedar (cf. 14:1 and the role of King Hiram in building David’s palace).

Nathan enters the scene rather abruptly in the narrative (17:1–2). Along with his contemporary Gad (cf. 21:9), he is identified as a “prophet” or spokesperson for God. Nathan’s role as God’s messenger frames the oracle. First Nathan receives a message from God (17:3), then he responsibly discharges his commission by faithfully reporting the revelation verbatim to King David (17:15). The introductory and concluding verses referencing Nathan are more than bookends for the dynastic oracle promising perpetual kingship to the line of David. The “word of God” formula (17:3) and the technical term “revelation” (lit., “vision”, 17:15; Heb. ḥazon) authenticate the divine origin of the message.

The idea behind the word “prophet” (nabiʾ ) in the Old Testament world is that of a servant who stands in the council of the gods and then reports exactly what he heard as a divine messenger or herald. Nathan is a strategic religious-political adviser in the early Hebrew monarchy as evidenced by his role in securing Solomon’s succession to David’s throne (cf. 1 Kings 1). Elsewhere we learn that Nathan the prophet is also a court historian, since the Chronicler references his “records” (cf. 1 Chron. 29:29; 2 Chron. 9:29). The combined good intentions of King David and the blessing of the prophet Nathan, however, are rebuffed by God. Curiously, there is no reference here to any “inquiry” of the Lord, despite David’s insistence that with the installation of the ark Israel will again inquire of God (cf. 1 Chron. 13:3).

The oracle hinges on word “build” (bnh). David will not build a temple for God (17:4), but God will build a royal dynasty from the family of David (17:10). Previously God’s presence has not been localized permanently at one specific geographical site. Rather, God moved with his people Israel as they traveled from Egypt after the Exodus and slowly wrested the land of Canaan from the indigenous population (17:5–7). Eventually the Mosaic tent-shrine came to be located more or less permanently in Shiloh and later Gibeon (but with the understanding that Yahweh would one day choose a dwelling place for his name, cf. Deut. 14:24; 16:2). The phrase “from one dwelling place to another” (1 Chron. 17:5) is difficult in Hebrew. The expression (lit., “from tent to tent and tabernacle”) probably refers to the gradual replacement of the Mosaic tabernacle with another tent-sanctuary as the materials of the Exodus tent-shrine deteriorated over the intervening centuries from Moses to Samuel.

The idea of a permanent and centralized structure for the worship of Yahweh is not the issue in God’s veto of David’s plan to build a temple. The problem is not the erection of a temple for Yahweh, but David. David’s legacy as a warrior means he will serve only as Solomon’s contractor for the building of the temple (cf. 22:8; 28:3). It appears that the construction of a permanent sanctuary or temple for the worship of God is connected to Israel’s secure position in the land of covenant promise (17:9–10). Unlike the era of the judges (“leaders,” 17:10), the Israelites are no longer oppressed by the neighboring people groups. God enables David to achieve this relative peace and safety by cutting off and subduing Israel’s enemies (17:8), as reported in the account of his successful military campaigns (chs. 18–20).

The promise of an offspring to succeed David on the throne of Israel echoes God’s similar promise to Abraham and Sarah (cf. Gen. 12:1–3). King David has the assurance of God that despite his own death, his dynasty will be firmly established (1 Chron. 11:11). According to Selman, this marks the third reason why God amends David’s proposal to build a temple in Jerusalem.37 Yahweh’s priority to build a house for David takes precedence over the construction of a permanent sanctuary. Lasting and appropriate Israelite worship of God must be founded on righteous leadership. The temple as “God’s house” can have significance for God’s people only after God has built “David’s house.”

The language of covenant adoption (17:13a) means the royal line of David will enjoy a privileged status as adopted sons of Yahweh (cf. Ps. 2:7; 89:27). The irrevocable steadfast “love” (ḥesed) of Yahweh means David’s family will avoid the tragic experience of King Saul—divine disapproval and rejection (17:13b). The final verse of the dynastic oracle contains a significant divergence from the Samuel parallel, with the shift to “my [i.e., God’s] house and my kingdom” (17:14) from “your [i.e., David’s] house and your kingdom” (2 Sam. 7:16). Yahweh is the true king of Israel, and as Williamson has rightly noted, legitimate and successful kings will be those confirmed and established by God himself.38

Biblical commentators have noted a high degree of correspondence between David’s prayer in 1 Chronicles 17:16–27 and its precursor in 2 Samuel 7:18–29. This is the first of several prayers offered to God by Israelite kings inserted in the Chronicler’s retelling of Israelite history. In fact, this is a subtle agenda item of the Chronicler—to draw the people of postexilic Judah back into conversation with God through prayer. The emphasis on prayer fits naturally into his concern for worship renewal because prayer ultimately issues in the glory of God (17:24).39

Balentine has identified David’s prayer as “formal prayer” or more liturgical-type prayer in contrast to “the single-response” type prayer or more conversational prayer of the Old Testament.40 It has various elements. The description is an account of the situation or circumstance giving rise to the formal prayer. In this case, the oracle of Nathan announcing God’s covenant with the house of David constitutes the description of the prayer (17:3–15).

The introduction to the prayer precedes its text and calls attention to the content of the prayer. The introduction to David’s prayer is brief and implies that he has entered the newly constructed tent-shrine in Jerusalem to offer his supplication (17:16a).

The invocation or address to God (17:16b–19) sets the tone of the prayer. David’s response to God’s gracious overture to establish his dynasty forever is one of self-deprecation in comparison to Yahweh’s benevolence. According to Japhet, David’s self-abasement sets a tone of reconciliation for the prayer, a “resignation to the will of God” in the decision concerning the building of the temple.41

The declaration serves either to praise God or justify the suppliant’s petition. Here in David’s prayer the declaration (17:20–22) praises the uniqueness of God and his power as revealed in Hebrew history. The thumbnail sketch of Israelite history highlights the Exodus, when God “redeemed” a people for himself, and makes an allusion to the Conquest and settlement period of the judges in the phrase “driving out nations” (17:21).

David’s petition is brief (17:23–24). He simply asks God to follow through and bring to completion what he has already promised: to raise up a descendant who will complete the task of building the temple and to establish firmly an everlasting Davidic dynasty.

The final structural element of the formal prayer is the recognition of God’s response to the prayer (17:25–27). Unlike the Samuel parallel (cf. 2 Sam. 7:29), David acknowledges that he has already received a partial answer to his prayer (1 Chron. 17:27). God has blessed David’s house in that his divine promise will not fail (17:19, 23). Beyond this, God has blessed David in elevating him to king over Israel and enabling him to transfer the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem. The conclusion of David’s prayer is a doxology of sorts, as the word “bless” (brk) occurs three times in the final verse (17:27). David understands all this is the gracious work of God, not the genius of human scheming or the chance of fate.

Doubtless, the Chronicler expects his audience to learn (or be reminded of) basic theological truths embedded in David’s prayer. The first is a repeated message in Chronicles, given the emphasis on prayer in the books: God both hears and answers the prayers of the righteous by doing great things that ultimately bring glory to his name (17:19, 24, 26). The second is implicit in God’s promise to build a lasting Davidic dynasty. The covenant granted to the house of David establishes the rule of God on earth in theological principle through the nation of Israel, apart from any literal descendant of David ruling over the autonomous nation of Israel. For the Chronicler “the divine kingdom was still effective despite the depravations of the exile and the foreign imperial rule of his own day.”42 The present reality of the kingdom of God embodied in the nation of Israel is the cornerstone of the Chronicler’s theology of hope.

The repeated use of the word “forever” (ʿolam) points to the distant future and indicates the Chronicler’s message is intended for another audience as well (17:23, 24, 27). Previously, the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel attached messianic expectations to the promises of the Davidic covenant (cf. Jer. 23:5; 30:9; 33:21; Ezek. 34:23; 37:24). The New Testament recognizes Jesus Christ as the ultimate fulfillment of those promises. He is the heir of David, and he inherited the throne of King David (Luke 1:32). Jesus is both the Son of David (Matt. 1:1) and the Son of God charged to build and oversee the very “house” of God (Heb. 3:6). God continues to build his “house,” the church, through the Son of David—a spiritual house that will prevail against the opposition of hell itself (Matt. 16:18; Eph. 2:21; 1 Peter 2:5)!

Bridging Contexts

THE TABERNACLE or tent-shrine described in detail in Exodus 25–40 was designed to symbolize the active presence of God among his people. In fact, Exodus 25:8 specifies the basic purpose of this portable worship center as one of giving God an “address” in the Israelite community: “Then have them make a sanctuary for me, and I will dwell among them.”

This sanctuary was also called the Tent of Meeting, because it was there that God convened his assemblies with Israel. The Levitical priesthood was ordained to represent the people before God and to mediate the divine presence in the covenant community. In one sense, God’s presence associated with the tabernacle and symbolized in the cloud of glory that resided there (Ex. 40:34–38) was part of the developing “Immanuel theology” of the Old Testament. This progressive revelation of an incarnational divine presence aimed at restoring the intimate fellowship enjoyed by God and humanity in the pre-Fall garden experience. The “Immanuel theology” of the Old Testament was ultimately fulfilled in Jesus Christ (John 1:14; cf. Isa. 7:14).

King Solomon’s prayer of dedication for the Jerusalem temple echoes this theme: “I have indeed built a magnificent temple for you, a place for you to dwell forever” (1 Kings 8:13). Interestingly, the parallel passage in Chronicles describes the function of the temple as a repository or resting place for the ark of the covenant—the very “footstool of our God” (1 Chron. 28:2). Thus, the ark was both “throne” and “footstool” of Yahweh (cf. 2 Kings 19:15). The Chronicler appropriately identifies the ark of the covenant as God’s footstool because his divine presence was specifically associated with this piece of tabernacle furniture as the place where God met with his people: “There, above the cover [of the ark of the Testimony] between the two cherubim that are over the ark of the Testimony, I will meet with you” (Ex. 25:22).

Practically speaking during biblical times, the royal footstool supported a king’s feet as he sat on his throne. According to Fabry, the installation of a royal throne and its footstool in a city or territory was also the equivalent of establishing residence and confirmed the ruler’s permanent sovereignty in that domain.43 The portrayal of a king seated on his throne with feet resting on the footstool represented, through symbol, the reality of royal authority in that city or region and the peace and prosperity enjoyed by the loyal subjects of the kingdom. In addition, the footstool was a sign of humility and servitude on the part of the conquered peoples within that king’s realm.

By logical extension from the particular to the universal, the footstool motif associated with the ark of the covenant prescribed the realm of God moving outward in an ever-expanding circle. The jurisdiction of God included the Jerusalem temple housing the ark (Ps. 132:7), but extended to Mount Zion or the city of David where the temple was eventually built (Lam. 2:1), and ultimately reached out to the whole earth (Isa. 66:1).

Belief strives for embodiment in conventional and tangible modes of expression. For this reason, symbolism has been a part of biblical religion from its beginnings because it is the vehicle of revelation and the language of faith. As vehicles of revelation, symbols summarize and interpret human experience and interaction with God. As part of the language of faith, symbols interpret the holy, the eternal, and the grace and righteousness of God.

Schaper understands symbolism as an object, act, or word that stands for, suggests, or represents something else.44 Thus, a sign is something practical and visible that essentially conveys information leading to personal action. For instance, the fish is a religious sign in that as a badge or emblem it conveys information about one’s identity as a Christian. Kooy has attempted to more precisely distinguish between sign and symbol in the Old Testament: “The religious symbol points beyond itself to reality, participating in its power, and makes intelligible its meaning. As such it goes beyond a sign or an image.”45 For example, the dove is a religious symbol since it incarnates the reality of the Holy Spirit (cf. Matt. 3:16). In other words, the sign may represent reality, whereas the symbol embodies it.

As ancient Israel’s most beloved poet, King David is well acquainted with the value of symbolic language. He understands the power inherent in word pictures for communicating theological truths, whether the sterling character of God (Ps. 18:1–2, 25, 30–31) or the faltering faith of the righteous (51:7–8). For David, the procession of the ark of the covenant into Jerusalem for eventual installation in a central sanctuary is both sign and symbol. As a sign, the ark of covenant serves both as a reminder of Israel’s Exodus experience and as a testimony of God’s holy presence among his people. The return of that sign of divine immanence to the religious life of Israel will stir the people to action—of once again recognizing Yahweh’s kingship by affirming their allegiance to him and demonstrating their loyalty to him by complying with the stipulations of his covenant.

As a symbol, the ark of the covenant embodies the theological truth of God’s residency in the midst of Israel. More important, the footstool motif associated with the ark validates the reality of Yahweh’s sovereign rule over creation and thus becomes an emblem of Israel’s submission and loyalty to God as king. Based on the instructions of the prophet-priest Samuel, David knows that kingship in Israel can only succeed as the people acknowledge God’s presence in their midst by the response of obedience to his commandments (1 Sam. 12:14–15). For King David, the processional celebrating the entry of the ark of the covenant into Jerusalem is a grand object lesson that dramatically portrays the vital relationship between the recognition of God’s presence and God’s rule.

THE VALUE OF SYMBOLS. In an important book addressing communication theory and practice, Pierre Babin has analyzed the impact of technology on religious communication in this age of electronic media. He has identified two types of language: the conceptual and the symbolic. Conceptual language may be defined as that form of communication “that provides an abstract, limited, and fixed representation of reality.”46 Symbolic language is “full of resonances and rhythms, stories and images, and suggestions and connections.”47

The rise of the media civilization is changing “our historical times into psychological times, and … those obliged to receive communication into those interested in receiving it.”48 This paradigm shift from conceptual to symbolic language has awakened an “interiority” in contemporary (postmodern) society that places an emphasis on feelings, imagination, and experience. Babin concludes his study of religious communication by prophetically calling the Christian church to rediscover the value of symbolic language for the sake of religious education in this postmodern electronic age.