Chapter 16

Distributing Your Product Where Your Customers Are

In This Chapter

Building your business with strong distribution strategies

Building your business with strong distribution strategies

Finding distributors and retailers

Finding distributors and retailers

Considering the best marketing channel structure and maximizing retail sales

Considering the best marketing channel structure and maximizing retail sales

Thinking about point-of-purchase incentives and displays

Thinking about point-of-purchase incentives and displays

The companies with the widest distribution are often the most successful because that distribution system gives them access to so many potential customers. Often the easiest way to grow your sales and profits is to improve your distribution systems. Adding retailers (or distributors if you’re a B2B marketer) and increasing your accessibility on the web are two good ways to expand distribution. If you sell to other businesses, then you can expand your network of salespeople or work with a large distribution company to increase the reach of your distribution system.

In this chapter, I share ways of reaching prospects both in the real world and on the web to increase your potential customer base. Distribution can help make your offerings more visible and accessible, such as by cuing up your product in a customer’s search on Amazon or making sure your product can be found and evaluated on the shelves of stores. For business-to-business marketers, distribution is also important and may mean getting in front of purchasing managers at conventions and in industry and trade showrooms or events as well as in online directories. As with all the other elements of marketing, innovations are changing distribution, and this chapter helps you consider web options, 3D modeling, and augmented reality along with more conventional options.

Taking a Strategic Approach

You need to decide how broadly to distribute your product (or service). To do so, it helps to have a firm grasp of the myriad distribution choices available to you. After you understand the different options, you can select the strategy that’s right for your organization. Following are some of the main distribution strategies and advice as to when and why you may want to implement them:

- Selective distribution strategy: This strategy focuses on a small number of outlets and often creates a sense of scarcity, allowing for higher pricing and prestige branding. An old saying among entrepreneurs advises to “Stay small and keep it all.” Does this strategy fit your marketing model and brand? Will it bring you enough business, or do you need more volume?

- Exclusive distribution strategy: This strategy is the extreme version of a selective strategy, in which you sell through one or a few specialized distributors only. You may make your product available through a boutique store in a major city or through a web or eBay store. If you have a unique product or service, why not limit the distribution and make customers come to you? This strategy gives you low costs and lets you support a relatively high price, so it can be highly profitable — but only if your product is special enough to make customers want to go looking for it.

- Intensive distribution strategy: This strategy (the opposite of selective distribution) aims to flood the market by making your product widely available in as many outlets as possible. If you offer a retail product to consumers, intensive distribution probably means getting onto the roster of accepted vendors for one or more of the giant retail chains. They’re the key to high retail volume in the United States today, but they require you to use their software and systems so they can pull inventory from your warehouse as needed. Ramping up to the scale needed to do business with a giant chain is costly if you’re a small business, so you may want to start with a selective distribution strategy and gain some experience and success before approaching the largest retail chains in your market.

- 80/20 strategy: This strategy applies to distributors. You get 80 percent or more of your sales from just 20 percent of your distributors. Giving those hardworking top distributors plenty of attention, excellent service, and excellent trade deals (see Chapter 15) is a good strategy. You want to develop a strong personal relationship with them because if they know you, they’re more likely to get in touch with helpful news or ask for your assistance with a problem. To do so, invest in wining and dining them and spending authentic time with them. After you give your top distributors plenty of attention, focus on a few of the low-producing ones and see whether you can move them into the high-producing category. If you can get 30 percent of your weaker distributors to sell at high volume, you can boost sales by an average of 50 percent, which is a good return for your investment in strengthening your distributor network.

You also have to decide whether you want to develop parallel distribution channels, also sometimes called competitive channels. Traditionally, a manufacturer would never sell direct to consumers if it also sold through wholesalers and retailers, so as to avoid competing with its own distributors who may get mad and stop selling its products. But parallel channels are increasingly common and accepted. For example, Apple sells through retail distributors, through its own Apple stores, through retail computer web stores, and through its own website.

Parallel distribution channels often lead to issues and tensions between company-direct and partner sales, but if you make an effort to communicate frequently and negotiate in good faith, such problems can almost always be worked out.

- Expand your distribution network. If you can add distributors or get more out of the ones you have, you may be able to make your product available to more people and increase your sales. Also consider boosting availability on the web (see Chapter 10) and using more direct-response marketing (see Chapter 13) and events (such as trade shows; see Chapter 12), which bypass distributors and reach out directly to customers.

- Move more inventory, more quickly. Increasing the availability of products in your distribution channel can also help boost sales and profits. Can you find ways to get more inventory out there? Can you speed the movement of products out to customers so they feel they can more easily find your product when they need it? Either strategy can have a dramatic impact on sales by allowing more customers to find what they want more easily when and where they want it.

- Increase your visibility. Another way you can use distribution strategies to boost sales is to increase the visibility of your product or service within its current distribution channel by making sure it’s better displayed or better communicated. Many retail chain stores provide better shelving (such as end-cap displays or eye-level shelving with a sign) if you offer them special promotional discounts or cooperative advertising fees, so see whether you can take advantage of one of their programs.

- Target larger or more desirable customers. Perhaps you can find a way to shift your distribution slightly so as to give you access to more lucrative customers. A consultant I know who helps small businesses with their hiring and employment issues is beginning to visit the human resources directors of large businesses in her area to explore what she can do for them. One contract with a big firm may be as valuable to her as 10 or 20 smaller clients, so this new effort to reach out to the largest companies in her area may grow her business significantly.

Tracking Down Ideal Distributors

Distributors want items that are easy to sell because customers want to buy them. It’s that simple. So the first step in getting customers on your side is to make sure your product is appealing. (See Chapter 14 for help making your brand stand out.) After you’re confident you have something worth selling, ask yourself which distributors can sell it most successfully. Who’s willing and able to distribute for you? Are wholesalers or other intermediaries going to be helpful? If so, who are they and how many of them can you locate? Phone companies traditionally publish business-to-business telephone directories by region for most of the United States (call the business office of your local phone company to order them); these directories often reference the category of intermediary you’re looking for in their Yellow Pages sections. Or cruise the web to track down possible distributors more quickly.

Here are some additional suggestions for locating your dream distributors:

- Reach out to a trade association or trade show specializing in distributors in your industry. For example, the International Foodservice Distributors Association (www.ifdaonline.org) puts on an annual conference for food distributors. A couple of days at an event like that, and you can locate dozens of possible distributors for your products.

- Attend major conventions in your industry. Hop on a plane, bring product samples and literature, put on comfortable shoes, and walk around the convention hall until you find the right distributors.

Contact the American Wholesale Marketers Association. The AWMA publishes a member directory and stages a number of conferences and expos. Find out more about the AWMA by calling 703-208-3358 or by visiting www.awmanet.org.

Contact the American Wholesale Marketers Association. The AWMA publishes a member directory and stages a number of conferences and expos. Find out more about the AWMA by calling 703-208-3358 or by visiting www.awmanet.org.- Consult any directory of associations for extensive listings. Such directories are available in the reference sections of most libraries. You can also go to the American Society of Association Executives’ Gateway to Associations, a web database found at www.asaecenter.org/directories/associationsearch.cfm.

Understanding Channel Structure

Efficiency is the driving principle behind distribution channel design. (Channel refers to the pathways you create to get your product out there and into customers’ hands.) Traditionally, channels have evolved to minimize the number of transactions because the fewer the transactions, the more efficient the channel.

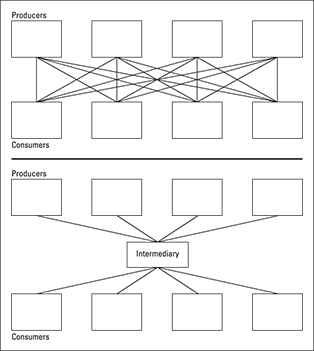

As Figure 16-1 shows, a channel in which 4 producers and 4 customers do business directly has 16 (4 × 4) possible transactions because each producer has to make four separate transactions to get its product to all four consumers. In reality, the numbers get much higher when you have markets with dozens or hundreds of producers and thousands or millions of customers.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 16-1: Reducing transactions through intermediaries.

You lower the number of transactions greatly when you introduce an intermediary (someone who handles the business transactions for you) because now you only have to do simple addition rather than multiplication. In the example shown in Figure 16-1, you need only 8 (4 + 4) transactions to connect all 4 customers with all 4 producers through the intermediary. Each producer or customer has to deal with only the intermediary, who links him to all the producers or customers he may want to do business with.

Although intermediaries add their markup to the price, they often reduce the overall costs of distribution because of their effect on the number of transactions. Adding a level of intermediaries to a channel reduces the total number of transactions that all producers and customers need to do business with each other.

This example is simplistic, but you can see how the logic applies to more complex and larger distribution channels. Introduce a lot of customers and producers, link them through multiple intermediaries (perhaps adding a second or third layer of intermediaries), and you have a typical indirect marketing channel (one involving intermediaries, as opposed to a direct marketing channel where you handle customers). Odds are you have some channels like this one in your industry.

Many channels are simpler and shorter than they used to be because handling numerous transactions is easier than it used to be. For example, Wal-Mart sources directly from manufacturers in many cases, relying on them to provide just-in-time deliveries into inventory in response to electronic messages. In the past, a retailer may have gone through a wholesaler who did business with manufacturers.

- Finding more customers for your product than you can on your own

- Researching customer attitudes and desires

- Buying and selling

- Breaking down bulk shipments for resale

- Setting prices

- Managing point-of-purchase promotions (which I cover in the section “Stimulating Sales at the Point of Purchase,” later in the chapter)

- Advertising at the local level (pull advertising, which is designed to bring people to a store or other business)

- Transporting products

- Inventorying products

- Financing purchases

- Qualifying sales leads (separating poor-quality leads from serious customers)

- Providing customer service and support

- Sharing the risks of doing business

- Combining your products with others to offer appropriate assortments

Reviewing Retail Strategies and Tactics

If you decide to improve sales at a retail store and you bring in a specialized retail consultant, you may soon be drawing planograms of your shelves (diagrams showing how to lay out and display a store’s merchandise) and counting SKUs (stock-keeping units — a unique inventory code for each item you stock). You may also examine the statistics on sales volume from end-of-aisle displays (higher sales) versus middle of the aisle (lower sales), and from eye-level displays (higher sales) versus bottom or top of the shelf (lower sales). Great. Go for it. However, I have to warn you that although a technical approach has its place, you can’t use this method to create a retail success story. The following sections show you why traffic flow is so important and how to capitalize on that traffic with the right merchandizing strategies, store atmosphere, and pricing.

Looking for heavy traffic

Traffic is a flow of target customers near enough to the store for its external displays and local advertising to draw them in. You want a great deal of traffic, whether it’s foot traffic on a sidewalk, automobile traffic on a road or highway, or virtual traffic at a website. Retailers need to have people walking, driving, or surfing into their stores (see Chapter 10 for more on web marketing). Customers don’t come into a store or onto a website in big numbers unless you have plenty of people to draw from, so you need to figure out where high traffic is and find a way to get some of it into your store.

You also wouldn’t dig a huge reservoir beside a small stream. You must suit your store to the amount and kind of traffic in its area — or else move to find more appropriate traffic. If you’re in a small town, don’t open a highly specialized store that appeals to only a few percent of shoppers, because you won’t have enough to keep you in business. A restaurant is a good option for a small town because just about everyone likes to eat out from time to time. If, however, you’re determined to open a specialized store, such as a store for rock collectors or a boutique specializing in trendy clothing for pregnant women, then look for a high-traffic location in a major mall or in the shopping district of a mid-sized or large city.

You can optimize your business in any particular location by making sure your store has enough appeal to draw a healthy share of the shopping traffic in the area. The ultimate trick is to make your store and its merchandise so appealing to sell that people go out of their way to visit the store. This attraction power is termed pull or draw, and few retail concepts are so unique that they can draw traffic from beyond their immediate area. But some do.

For example, a jewelry store in my town has such a good selection of merchandise that it draws far more traffic than the surrounding stores. And its owner carefully stimulates this traffic through a direct-mail program and by giving the store a unique and highly visible appearance — the store is in a huge, ornate, yellow Victorian house with lots of ground-floor windows displaying interesting gifts. The store’s strategy focuses on the one thing that old joke about retailing leaves out: the store concept. The concept is a creative mix of merchandising strategy and atmosphere (see the following sections for more on these) that you can use to give your store higher-than-average drawing power. An exciting, well-executed concept makes shopping an enjoyable event and can boost traffic and sales tenfold.

Developing merchandising strategies

Merchandising is the set of activities used to sell products at retail. Whether you retail services or goods, you need to think about your merchandising strategy. You do have one, whether you know it or not — and if you don’t know it, your strategy is based on conventions in your industry and needs a kick in the seat of the pants to make it more distinctive. Merchandising strategy, the selection and assortment of products offered, is an important source of competitive advantage or disadvantage for retailers.

I suggest a creative approach to merchandising. The majority of success stories in retail come about because of innovations in merchandising. So you should be thinking of new merchandising options daily — and trying out the most promising ones as often as you can afford to. The next few sections describe some existing strategies that may give you ideas for your business. Perhaps no one has tried them in your industry or region, or perhaps they suggest novel variations to you.

General merchandise retailing

The general merchandise retailing strategy works because it brings together a wide and deep assortment of products, thus allowing customers to easily find what they want — regardless of what the product may be. Department stores and variety stores fall into this category. Hypermarkets, the European expansions of the grocery store that include some department store product lines, are another example of the general merchandise strategy. In the United States, Wal-Mart is a leader because it offers more variety (and often better prices) than nearby competitors. Warehouse stores, such as Home Depot and Staples, give you additional examples of general merchandise retailing. And as this varied list of examples suggests, you can implement this strategy in many ways.

Limited-line retailing

The limited-line retailing strategy emphasizes depth over variety. For example, a bakery can offer more and better varieties of baked goods than a general food store because a bakery sells only baked goods. Limited-line retailing is especially common in professional and personal services. Most accounting firms just do accounting. Most chiropractic offices just offer chiropractic services. Most law firms just practice law. For some reason, I’ve seen little innovation in the marketing of services.

After all, the limited-line strategy only makes sense to customers if they gain something in quality or selection in exchange for the lack of convenience. Regrettably, many limited-line retailers fail to make good on this implied promise — and they’re easily run over when a business introduces a less-limited line nearby. What makes, say, the local stationery or shoe store’s selection better than what a Staples or Wal-Mart offers in a more convenient setting? If you’re a small businessperson, you should make sure you have plenty of good answers to that question! Know what makes your merchandise selection, concept, or location different and better than that of your monster competitors — then make sure your potential customers know it, too.

Scrambled merchandising

Consumers have preconceived notions about what product lines and categories belong together. Looking for fresh produce in a grocery store makes sense these days because dry goods and fresh produce have been combined by so many retailers. But 50 years ago, the idea would’ve seemed radical because specialized limited-line retailers used to sell fresh produce. When grocery stores combined these two categories, they were using a scrambled merchandising strategy, in which the merchant uses unconventional combinations of product lines. Today, the meat department, bakery, deli section, seafood department, and many other sections combine naturally in a grocery store. And many stores are adding other products and services, such as coffee bars, banks, bookshops, dry cleaners, shoe repair, hair salons, photographers, flower shops, post offices, and so on. In the same way, gas stations combine with fast food restaurants and convenience stores to offer pit stops for both car and driver. These scrambled merchandising concepts are now widely accepted, so see whether you can create a combination of your own that appeals to consumers in your area.

Creating atmosphere

A store’s atmosphere is the image that it projects based on how you decorate and design it. Atmosphere is an intangible — you can’t easily measure or define it, but you can feel it. And when the atmosphere feels comforting, exciting, or enticing, this feeling draws people into the store and enhances their shopping experiences. So you need to pay close attention to atmosphere.

Sophisticated retailers hire architects and designers to create the right atmosphere and then spend far too much on fancy lighting, new carpets, and racks to implement their plans. Sometimes this approach works, but sometimes it doesn’t. And at any point in time, most of the professional designers agree about what stores should look and feel like, which means your store looks like everyone else’s.

Perhaps you can honestly and simply provide some entertainment for your customers. Just as a humorous ad entertains people and attracts their attention long enough to communicate a message, a store can entertain for long enough to expose shoppers to its merchandise. For example, some Barnes & Noble bookstores create comfortable, enclosed children’s book sections with places to play and read (or be read to) so families with young children can linger and enjoy the experience. When consumers can shop online from the comfort of home, it’s important to make your store a special place worth going to.

Positioning your store on price

Retail stores generally have a distinct place in the range of possible price and quality combinations. Some stores are obviously upscale boutiques, specializing in the finest merchandise for the highest prices. Others are middle class in their positioning, and still others offer the worst junk from liquidators but sell it for so little that almost anybody can afford it. In this way, retailing still maintains the old distinctions of social class, even though those class distinctions are less visible in other aspects of modern U.S. and European society.

As a retailer, this distinction means that customers get confused about who you are unless you let them know where you stand on the class scale. And that means you have to know where you stand, so ask yourself whether your store has an upper-class, upper-middle-class, middle-class, or lower-middle-class pedigree. Do you see your customers as white collar or blue collar? And so on.

Stimulating Sales at Point of Purchase

The point of purchase (POP) is the place where customer meets product. It may be in the aisles of a store or even on a catalog page or computer screen, but wherever this encounter takes place, the principles of POP advertising apply. Table 16-1 shows you just how important point of purchase is; it gives you an idea of how much (or how little) shoppers’ purchases are influenced by their predetermined plans. The statistics are from Point of Purchase Advertising International; its members are professionals working on POP displays and advertising, so the organization does a fair amount of research on shopping patterns and how to affect those patterns at points of purchase.

Table 16-1 Nature of Consumers’ Purchase Decisions

|

Supermarkets Percent of Purchases |

Mass Merchandise Stores Percent of Purchases | |

|

Unplanned |

60% |

53% |

|

Substitute |

4% |

3% |

|

Generally planned |

6% |

18% |

|

Specifically planned |

30% |

26% |

You can sway purchasing decisions your way and boost sales by designing appealing displays that consumers can pick your products from. Free-standing floor displays have the biggest effect, but retailers don’t often use them because they take up too much floor space. Rack, shelf, and counter-based signs and displays aren’t quite as powerful, but stores use these kinds of displays more often than free-standing displays.

Retailers are likely to use any really exciting and unusual display if they think it boosts store traffic and sales or boosts the sale of the products it promotes. Exciting displays add to the store’s atmosphere or entertainment value, and store managers like that addition. Creativity drives the success of POP displays. A good display should

- Attract attention: Make your displays novel, entertaining, or puzzling to draw people to them.

- Build involvement: Give people something to think about or do to involve them in the display.

- Sell the product: Make sure the display tells viewers what’s so great about the product. It must communicate the positioning (you better hope you have one!). Simply putting the product on display isn’t enough. You have to sell the product, too, or else the retailer doesn’t see the point. Retailers can put products on display themselves — they want a marketer’s help in selling those products.

As you work on a POP design, check with some of your retailers to see whether they like the concept. Between 50 and 60 percent of marketers’ POPs never reach the sales floor. If you’re a product marketer who’s trying to get a POP display into retail stores, you face an uphill battle. The stats say that your display or sign needs to be twice as good as the average, or the retailer simply tosses it into the nearest dumpster.

The trend is toward simpler, more direct channels, and you need to be prepared to handle a large number of customer transactions to be in step with this trend. A good general rule for you as a marketer is to use only as many intermediaries and layers of intermediaries as seems absolutely necessary to reach your customers. Try to keep it simple and add more parties only if you can’t do it well yourself.

The trend is toward simpler, more direct channels, and you need to be prepared to handle a large number of customer transactions to be in step with this trend. A good general rule for you as a marketer is to use only as many intermediaries and layers of intermediaries as seems absolutely necessary to reach your customers. Try to keep it simple and add more parties only if you can’t do it well yourself.