APPENDIX IV: SLUDGE MAGIC VERSUS NATIVE AMERICAN BELIEFS

Chapter 5, “Black Magic,” deals with the deceptive nature of EPA’s lead abatement studies in African American communities, which it uses to argue that land application of sewage sludge (aka biosolids) reduces risks of lead poisoning. With respect to Native Americans, EPA’s promotion of pollutant-rich biosolids as being beneficial to land is more than just deceptive. It’s disrespectful of the reverence Native Americans have for their ancestors and the lands they once inhabited. And the agency’s history of covering up adverse health effects only perpetuates the kind of treatment American Indians have received from the US government since it removed them from their fertile lands and gave them barren wastelands in return.

A case in point is the towering pile of sewage sludge called “Mount San Diego,” which sits on the Torres Martinez Indian Reservation in Southern California. Members of numerous Native American tribes, environmental activists, and farm workers blockaded entrances to the site for fourteen days in October 1994 in an effort to shut down the operation. According to a fact sheet published by the Water Environment Federation (WEF), the reservation’s residents complained of “thick dust and clouds of flies,” along with adverse health effects, including allergic reactions, headaches, and nausea.1 To put down their complaints, the WEF pointed to tests conducted by federal and state agencies that purportedly showed that “composting at the Torres Martinez reservation caused no environmental damage or threat to human health.” It was yet one more example of the injustices EPA created from 1992 to 1999 when its Office of Water funded the WEF to investigate “biosolids horror stories” and issue “fact sheets” to inform the public of “what really happened.”2 The WEF, of course, never found any public health problems with land application of biosolids.

The enduring connection Native Americans have with the lands their ancestors freely roamed is eloquently expressed in popular versions of a speech attributed to Chief Seattle, a Suquamish Indian who sold his tribe’s land to the US government in the mid-1800s. The following excerpt serves as an example:3

Every part of this soil is sacred in the estimation of my people. Every hillside, every valley, every plain and grove, has been hallowed by some sad or happy event in days long vanished. Even the rocks, which seem to be dumb and dead as they swelter in the sun along the silent shore, thrill with memories of stirring events connected with the lives of my people, and the very dust upon which you now stand responds more lovingly to their footsteps than yours, because it is rich with the blood of our ancestors, and our bare feet are conscious of the sympathetic touch. . . . At night when the streets of your cities and villages are silent and you think them deserted, they will throng with the returning hosts that once filled them and still love this beautiful land.

A quarter of a century ago, the pastor of our small community church and I purchased a tract of wooded land in Oconee County, Georgia, that includes a stretch of Little Rose Creek. When we first looked at the property, he asked whether I thought it may have contained any Indian artifacts. I pointed to a small depression visible in a distance as a likely spot. As we approached it, we noticed a small, red projectile point laying in a small pocket of eroded clay. Since then, I’m continually reminded of the original inhabitants who took care of that land long before we built the church and my family picked out a spot to live near the creek. Having volunteered to help at archeological sites, I’ve learned to appreciate the artistic skill and craftsmanship exhibited by objects Native Americans fashioned from clay and stone. Each of them has a story to tell, and none tug at the heart more than some I’ve found along the creek bed.

Coming across evidence of daily life left behind by these original inhabitants is different from looking at artifacts in museums. There, I have no personal connection with the people who created the objects. But when I see them on the land where I live, I can almost sense the presence of those who lived there before me. Their tools and works of art have something important to say about the land, and the people who lived there in the distant past.

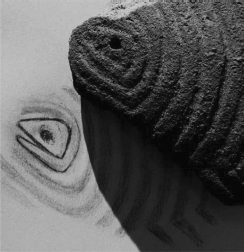

One shard of Indian pottery lying among the rocks in the creek was particularly heartrending. Under the rippling water I could see that its clay surface also formed ripples, which radiated from a tiny hole in the design. It was once part of an elaborately decorated pot approximately fifteen inches in diameter. As I lifted the fragment out of the water, I noticed that the hole represented the eye of a fish breaking the water’s surface, as if caught on a line. Looking back, I can’t help but think about the “happy event in days long vanished” that it represents in the life of someone from another era—someone whose ancestors and descendants loved the creek’s clear, flowing water and surrounding woodland for many generations, whose people will never get to experience such happiness in that place again. To me, it tells the story of a way of life that has been lost, a door forever shut.

Pottery shard with fish-head design. Courtesy David Lewis.

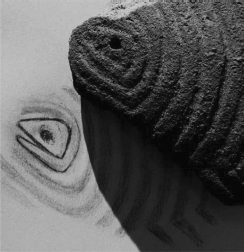

Rock bearing a Christian cross found among Indian artifacts. Courtesy David Lewis.

Nearby, I noticed a flat rock about one-and-a-half inches thick with beveled ends that appeared to have a petroglyph that told a different story. The beveled underside fit comfortably in the palm of my hand. Its face was flat like a tablet, and bore what looked like the chiseled image of a Christian cross about 2.5 × 5 inches long. Perhaps some early homesteader used it to mark a small grave. Or, because it was nestled among Indian artifacts, maybe one of the last remaining Native Americans living in the area gouged it with an iron tool as he sat on the banks and pondered the strange God of his enemies. Later, as I traced the grooved lines with my finger, I thought about a part of Chief Seattle’s speech that contrasts the earthly handiwork of the Great Spirit with that of Abraham’s God.

The white man’s God cannot love our people, or he would protect them. They seem to be orphans who can look nowhere for help. . . . Your religion was written upon tablets of stone by the iron finger of your God so that you could not forget. . . . [We] could never comprehend or remember it. Our religion is the traditions of our ancestors . . . written in the hearts of our people.

In the same area, the creek cuts though a layer of blue clay that formed at the end of the last Ice Age. There it revealed the broken mid-section of a Paleolithic blade or projectile point. Thin, and perfectly symmetrical, it proved that Indians had occupied this spot since the very earliest times of human history in North America. The story it tells is one of impending doom for all humanity. About twelve thousand years ago, these amazing people barely survived an asteroid or comet that impacted the Laurentide Ice Sheet covering what is now Canada. Other than bison, no other large mammals in North America escaped the fire and burning acid that rained down, and the prolonged darkness and deep freeze that followed. Yet, these earliest inhabitants were able to pick up their belongings and make their way from the Eastern Seaboard to find shelter in the mountains out West. It was no less of an achievement than our sending humans to the moon, and bringing them back alive.

Instead of acknowledging their great heritage, the managers of EPA’s biosolids program treat Native Americans not unlike their ancestors were treated under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Their ancient lands are being destroyed with municipal and industrial wastes. And their descendants who complain of poisoned soils and foul air on their reservations are just seen as obstacles standing in the way of the government’s plans to pollute those lands as well. Within EPA’s biosolids program, there is no reverence at all for the land, or any respect for the people who live on it. Until that changes, there remains no hope, neither for the land nor the people. Yet EPA’s biosolids program is just a microcosm of our federal government as a whole, and the governments of other highly industrialized nations. It would be far easier for them to put people on the moon than enable their populations to survive an event such as the one that befell Native Americans at the end of the last Ice Age. It shows how far removed modern technology is from integrating civilization with the natural world. And yet we all live on the brink of such events, which inevitably and suddenly come forth from the earth below and the heavens above from time to time.

One of the most rare and precious resources that our government held in its hands a century or two ago was the knowledge and understanding of our natural environment possessed by Native Americans. But, instead of protecting Native Americans, it set out to obliterate them. In doing so, it committed us all to a less secure future. Even today, we should take stock of what is left of this resource, and enlist Native Americans in an effort to figure out how to do what their ancestors did. Their enduring reverence for the land is just what EPA policymakers need to protect it for future generations to enjoy, and to serve as a safe haven when future cataclysmic events threaten our survival as a species once again.